As we’ve seen, nearly 75 percent of women with PCOS are overweight or obese, and frequently store that excess weight around their abdomens. Women who struggle with weight issues may feel they are weak, lack willpower, or have a psychological block that makes taking off just a few pounds seem like a task of epic proportions. This problem is especially common in women with PCOS, whose bodies often resist losing weight.

If the last paragraph describes you, take heart. A new approach combines the right foods with the right strategies—and it’s been successful for women with PCOS. The purpose of this chapter is twofold: (1) to give you the right foods to help you lose weight and (2) to supply you with the right strategies to help keep the weight off without hunger or deprivation. In chapter 7 we get around to eating the real food.

This chapter will help you gain an appreciation of optimal eating for weight control, showing you how to keep many of your favorite foods. Perhaps most significantly, the benefits you can derive from this book’s approach can last a lifetime. The eating plans and strategies will help you lose the weight you want and then will show you how to keep it off—all without feeling hungry or deprived. The latest research, some of which points to the role of genes in PCOS-related weight gain, can be overcome with a sound eating plan based on smart food strategies. It’s important to remember that genes impel; they don’t compel. With the right food management strategies, almost anyone suffering from PCOS can take control of her eating, her genetic influence, her metabolic resistance and, most importantly, her weight.

For what you will read in this chapter and the next, I am grateful for the direct participation of two health professionals whose knowledge in this area is much greater than my own. Stephen Gullo, Ph.D., contributed the concept of how foods affect us individually and why successful weight loss programs need to take into account the foods we have a history of abusing. President of the Institute for Health and Weight Sciences’ Center for Healthful Living in New York City, he is the author of the book The Thin Commandments (Rodale, 2005). The glycemic index, meal plans, recipes, and much else were contributed by Martha McKittrick, R.D., C.D.N., C.D.E. A staff dietitian at The New York Presbyterian Hospital for the past twenty years, she also counsels individuals in her private practice, physicians, corporations, and health clubs, and appears on numerous television, radio, and webcast programs. In my medical practice, both coordinate with me in the nutritional care of women with PCOS, so I know firsthand what healing wonders their nutritional counseling can produce.

Since many women with PCOS have trouble losing weight when their diet contains high or sometimes even moderate amounts of carbohydrates—especially the high-glycemic variety— it’s important that you follow a low-glycemic carbohydrate eating plan, eat small meals through out the day (three meals and two snacks are preferable), and always include some protein when you eat carbohydrates. Protein helps slow the absorption of sugar into the bloodstream. This program is ideal for women suffering from PCOS. It is based on low-fat protein; non-starchy green and white vegetables; fish oils from cold-water fish and seafood; white meat poultry; eggs and egg substitutes; low-fat, high-calcium dairy; cinnamon; and limited amounts of certain fruits.

We’ll show you not only how to lose weight, but how to keep it off. You’ll discover how to learn from your mistakes and not to feel defeated by them. Many women with PCOS who lose weight and gain it right back do so not because they’re planning to fail, but because they’re failing to plan. On the pages that follow you’ll learn unique, creative strategies that have worked for thousands of women with long histories of yo-yo dieting—many PCOS sufferers who have long despaired about ever achieving control over their weight.

As you read more, you’ll see how the strategies and eating plans reinforce one another. Your eating behavior and habits and the type of foods you choose are both critical for your long-term success at weight control. Whether you can change your genetic response to food is as yet unknown. However, your “metabolic resistance” to weight loss, as well as the sight, smell, taste, and texture of the foods that have sabotaged your weight, can be dramatically altered.

You simply need the right foods—the right way.

Food is a critical player in the PCOS drama. All the foods we eat have a direct impact on our hormonal system, and since it’s now known that the underlying cause of PCOS is an imbalance of sex hormones, the foods you eat can have an enormous impact on PCOS. The imbalance in PCOS patients is often linked with the way their bodies process insulin, the hormone that controls the amount of glucose that enters their cells. Many PCOS patients have too much insulin in their blood.

As you have read previously, many women with PCOS are insulin resistant, which makes it easy for them to put on weight that, unfortunately, is difficult to lose. Constantly fluctuating blood sugar levels often lead to food cravings, especially for carbohydrates, and elevated insulin levels cause the body to store more calories as fat. A recent study showed that women with PCOS are 40 percent less responsive to the hormones that help metabolize fat than healthy women, regardless of their weight.

For most people, thermogenesis (the rate at which food is metabolized) accounts for a large percentage of calorie burning after a meal. Thermogenesis is often greatly reduced in women with PCOS—their bodies simply do not burn up calories as quickly as those who do not have PCOS. As a result, their bodies store more of the calories from the foods they eat.

Another reason that the type of food you’re choosing is so essential in managing PCOS is that your weight and your percentage of body fat are factors in determining the severity of your symptoms. So weight management may be one of the most powerful ways for you to reduce the negative impact of PCOS and its symptoms in your life.

Studies have shown that the PCOS symptoms respond remarkably well to dietary changes. Overweight women with PCOS who lose weight have a corresponding decline in testosterone levels and their symptoms decrease. The loss of 5 to 7 percent of total body weight can cause more than two-thirds of women to resume ovulating, even some with long histories of infertility.

Many women are “fat phobic” and will go to any length to avoid consuming fat. Their diets consist mainly of grains (often refined grains), veggies, fruits, and lean protein, as well as a plethora of fat-free products—salad dressings, cheeses, ice cream, cookies, and so on. Not uncommonly, these women have frequent cravings and fluctuating energy levels. Others are “carb phobic,” with diets that contain large amounts of protein and fat but are almost devoid of carbohydrates, with the exception of low-carb products such as protein bars and other low-carb snacks. Many of these women report low energy levels.

Neither of these diets is ideal. Balanced meals work best in helping the majority of women control carb cravings, increase energy levels, and lose weight. By balanced, I mean meals that contain protein, fat, and carbs. Protein and fat help keep you feeling full longer. In addition, when eaten together with carbohydrates, they slow the rise and fall of blood sugar. The more gradual the rise in blood sugar, the less insulin your body produces. Carbohydrates provide your body with energy, so consuming too few carbs can cause headaches and low energy levels in some people. This is especially important if you exercise on a regular basis. Eating balanced meals can help keep your blood sugar stable for a longer period of time. This, in turn, can control hunger, decrease cravings, and promote better mood and energy levels.

The typical low-fat, high-carbohydrate weight loss diet is not the best choice for obese, insulin-resistant women. The majority of women with PCOS have more success in losing weight on a lower glycemic index diet. This is a diet plan that causes fewer sharp rises and falls of blood sugar.

Eating “healthier” carbs rather than sugary or refined carbs, as well as eating fewer carbohydrates overall, will reduce insulin secretion. Decreasing insulin levels can help to alleviate many of the symptoms of PCOS, including hunger and cravings. However, this does not mean that all women with PCOS need to be on a low-carb diet. Women who are lean and only slightly insulin resistant can do just as well on a nutritionally balanced diet that is moderate in carbs—again, focusing on “healthier” carbs. Bottom line: You need to find a plan that works best for you.

Some subjective indicators that the diet is working:

• decreased cravings

• increased energy levels

Some objective measures that the diet is working:

• weight loss

• decreased insulin levels

• more regular periods

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to the following plans. We all have different food likes and dislikes, and your lifestyle— whether you’re a stay-at-home mom or a frequent business traveler who rarely eats a home-cooked meal—affects your eating habits. Some of us are more active than others, which affects our caloric needs as well as the nutrient composition of our diet. In addition, our bodies do not respond in the same way to the same foods. For example, some women can incorporate moderatesized portions of carbohydrates such as pasta and bread into their diets without triggering cravings or the urge to eat more. Other women find that these same foods set off intense cravings or leave them feeling unsatisfied. Obviously, you want to avoid foods that cause uncontrollable cravings for more. Pay attention to how your body feels after eating and make adjustments to establish a plan that works for you.

Carbohydrates in food break down into sugar in your blood. For example, when you eat pasta, the flour from the pasta breaks down into glucose. This provides you with energy. The same thing happens when you eat a piece of fruit, drink a glass of milk, or eat jelly beans. All are converted to blood sugar. Your body then releases insulin to control the level of sugar in your blood.

In the past, it was believed that simple carbohydrates (called sugars) caused a more rapid rise of blood sugar than complex carbohydrates (called starches). However, recent research shows that this is not always the case. Not all foods that are chemically similar (for example, starches) necessarily affect blood sugar levels in the same way. For example, white rice causes a higher blood sugar response than white pasta. Potatoes can cause an even higher blood sugar response—similar to the response after eating table sugar. The carbohydrates that release sugar quickly into the bloodstream are the ones that cause sudden surges in insulin. Over time, those high surges of insulin can cause the body to become insulin resistant. Eventually that insulin resistance can lead to diabetes and other related illnesses. Health experts now understand that all carbohydrates are not the same, and that our bodies do not treat them in the same manner.

Glycemic index. The glycemic index (GI) measures how quickly a particular carbohydrate affects blood sugar levels. The higher the number, the quicker the rise in blood sugar. In general, starchy foods like refined grain products (for example, white rice) and potatoes have a high glycemic index. Milk, many fruits, and non-starchy vegetables such as greens have a low glycemic index, while whole grains, peas, and other legumes have a moderate or low glycemic index.

Glycemic load. The glycemic load (GL) assesses the impact of carbohydrates on blood sugar. It gives a more comprehensive picture than the glycemic index because it takes into account how much available carbohydrate is in a serving of food. Available carbohydrates are those that provide energy (starch and sugar), but not fiber. Foods that have a low GL almost always have a low GI. For more information on the glycemic index and glycemic load, check out www.mendosa.com. This Web site also lists the glycemic index and glycemic load of various carbohydrate-containing foods.

The majority of insulin resistant people find it easier to lose weight on a lower glycemic index diet. They report feeling more satiated, with fewer cravings and better energy levels. This is likely due to the lower glycemic index foods causing a slower rise of blood sugar, followed by a slower drop, which produces less insulin than rapid fluctuations. As we have already discussed, high levels of insulin can contribute to cravings, hunger, and fat storage.

Low glycemic diets contribute to better health in other ways:

• The Nurses’ Health Study found a relationship between high glycemic index diets and heart disease in women who were overweight or insulin resistant.

• Other studies suggest that high glycemic index foods may contribute to overeating and weight gain.

• Data from the Nurses’ Health Study also suggested that women who ate the least amount of foods with a high glycemic intake had a 50 percent lower risk of diabetes than those who ate the most.

• A study conducted by the American Institute for Cancer Research found that the women who ate the least amounts of high glycemic index carbohydrates were more than twice as likely not to have breast cancer as those who ate the most.

While the glycemic index can be a useful tool, keep in mind that it does have some limitations.

In assigning a number to a food, the glycemic index assumes that the food is eaten alone. In reality, however, we rarely eat a single food by itself. You don’t just have a baked potato for dinner. When other foods are eaten at the same time, the glycemic index of the particular food can change. Fat and fiber slow the process of digestion and thus lower the glycemic index of each of the foods involved. For example, a baked potato eaten alone causes a rapid rise of blood sugar. However, the rise is not as quick if you add a piece of broiled salmon and salad with olive oil, because the potato is digested more slowly.

The glycemic index is affected by how the food is processed, the way it is prepared or stored, and its ripeness. For example, pasta cooked al dente (firm) is absorbed more slowly than pasta that is overcooked. Another example: A banana that is barely ripe has a lower glycemic index than a very ripe banana.

The glycemic index of a food is an average of how many people respond to that food. Responses can be highly individual, so it is important for you to pay attention to how you feel after eating a particular food. For example, a sweet potato has a fairly low glycemic index, but if you do not find sweet potatoes especially filling or you have cravings soon after eating them, it’s best to avoid them.

Keep good nutrition in mind when using the glycemic index. Just because peanut M&M’s have a lower glycemic index than carrots does not mean they are a good snack choice!

• Limit or avoid sugary foods and drinks, as well as refined or heavily processed carbohydrates such as sugary sodas and white bread.

• Consume all carbohydrates in moderation. Although eating carbs with a lower glycemic index is recommended, eating large portions of that carbohydrate can still trigger excessive insulin surges.

• Select whole grains (whole wheat pastas, brown rice, wild rice, whole rye) over refined grains (plain pasta, white bread).

• Select higher fiber foods. Compare food labels to find the higher fiber product. Select whole grain breads, pasta, and crackers with at least 3 grams of fiber, and cereals with at least 5 grams of fiber per serving. Government guidelines recommend 25 to 30 grams of fiber a day; the average person takes in only 11 grams!

• Try to eat four or five moderate-sized meals or snacks as opposed to two or three large meals.

• Adding a little fat to a meal can lower the glycemic response. Focus on heart-healthy fats such as olive and canola oils, avocado, nuts, and nut butters. But remember portion control, because all fats are high in calories!

• Craving mashed potatoes? Try mashed yams, mashed turnips, or cauliflower.

You may see different glycemic index ratings for the same food if you check one list against another. Here’s why: There are two different glycemic index lists. One uses sugar as a benchmark, and the other uses white bread. The benchmark value of 100 is the standard against which all other foods on the index are measured. Experts could compile glycemic indexes based on orange juice (or honey, or some other food) as the benchmark of 100, and generate yet another set of values. The food scientists who created the existing indices chose sugar and white bread as benchmarks because they are two of the most widely consumed refined carbs. Both lists are valid and reliable for our purpose— just select the foods with a lower glycemic index number.

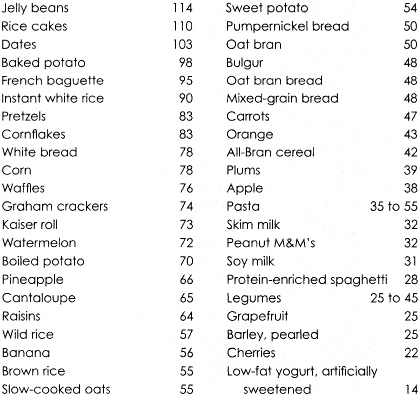

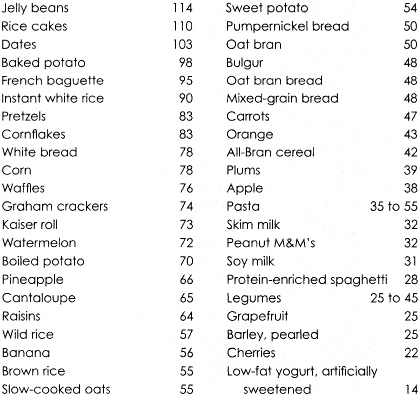

The following glycemic index uses white bread as a benchmark of 100. Also, as previously discussed, you may want to use the glycemic load, in place of the glycemic index, as a guide when selecting your carbohydrates.

GLYCEMIC INDEX OF FOODS, RANKED FROM HIGH TO LOW

A food with a glycemic index of less than 55 is considered a low glycemic food, while 56 to 69 is moderate and over 70 is considered high. Most non-starchy vegetables have a very low glycemic index.

Take a walk down the aisles in your local supermarket and you will be surrounded by packaged foods proclaiming their low-carb status—breads, cereals, salad dressings, candy bars, and so forth. Terms such as net carbs and impact carbs can be confusing to someone trying to watch her carbohydrate intake. Are these products really better than the regular product? The answer is … sometimes.

In response to the rising popularity of low-carb diets, food manufacturers have come up with their own definitions of what constitutes low carb. Unfortunately, the FDA has not set up regulations for low-carb claims as it has done for low-fat and low-sodium claims. In calculating net or impact carbs, most manufacturers take the total amount of carbs a product contains and subtract the fiber and sugar alcohols, as well as other ingredients such as glycerine or glycerol. It is thought that these ingredients, which are carbohydrates, have less of an impact on blood sugar. While it is true that some sugar alcohols have less of an impact on blood sugar levels than other carbohydrates, it is untruthful to say that sugar alcohols as a group have no affect on blood sugar whatsoever.

Sugar alcohol or polyols are hydrogenated carbohydrates that are used in foods mainly as bulking agents (to give foods texture) or sweeteners. Examples include sorbitol, mannitol, maltitol, and xylitol. Sugar alcohols are incompletely absorbed from the small intestine and provide 0.2 to 3.0 kcal/gram compared with the usual 4 kcal/gram provided by other carbohydrates. At this time, the FDA requires that food manufacturers count sugar alcohols as 2 kcal/gram. In short, sugar alcohols are not calorie free. Their glycemic effect varies according to type and your unique response to them. They also can cause gas or have a laxative effect in some individuals.

Glycerol or glycerine is chemically characterized as a polyol (sugar alcohol) with 4 kcal/gram. It is used in a variety of products, including nutrition or energy bars and frozen desserts. At this time, the FDA requires the glycerin content to be included in the total carbohydrate content.

Do fewer carbs mean fewer calories? In some cases, low-carb products do have fewer carbs than the regular version. Manufacturers can lower the carbohydrate content of a product by:

• substituting soy and wheat protein for flour.

• adding fiber from wheat bran and oat bran.

• adding high-fat ingredients such as oil and nuts, and decreasing the amount of carbohydrates.

• replacing sugar with sugar alcohols and artificial sweeteners.

However, this does not mean that low-carb products are lower in calories. As a matter of fact, many of the lower carb products have just as many calories as the regular version. For example, a slice of “low-carb” Atkins bread has 60 calories and 8 grams of total carbs—although a claim is made for only 3 net impact carbs. In comparison, a slice of conventional “diet” bread typically has 50 calories and 10 grams of carbs. Not a significant difference.

Tips to help you through the low-carb maze. The fact that a product’s label says it is low-carb does not necessarily mean that it is low-carb, low-calorie, or even healthful.

• Note the serving size. People often eat a whole bag thinking it is one serving, only to find out later it contained four servings!

• Pay attention to the total caloric content. Calories are still the most important factor when it comes to weight control. Even if a food is low in carbohydrates, it may not be low in calories, or a healthful choice.

• When choosing between two products, select the one with the higher fiber content. This is important when it comes to selecting cereals, breads, crackers, and so forth, because they can vary tremendously in fiber content. Higher fiber foods tend to have a lower glycemic index than lower fiber foods. In addition, fiber is important for good health.

• Look for fat content, especially saturated fat content. When the carb content is decreased, the fat content often increases. For example, compare the Skinny Cow Silhouette Fat Free Fudge Bar, which has 100 calories, 22 grams of carbs, and 0 grams of fat, to the Atkins Indulge frozen ice-cream bar, which contains 180 calories, 12 grams of carbs, and 16 grams of fat (12 of these fat grams are saturated). Some of you might select the Indulge bar because of its lower carb content. However, that would not be my recommendation in view of its high calorie and fat (especially saturated fat) contents.

If you’re counting grams of carbs. Some of you following lowcarb diets may be interested in counting grams of carbs. (Not everyone needs to do this!)

• Fiber. Since fiber has a minimal effect on raising blood sugar, some health care practitioners have suggested subtracting the grams of fiber from the total carbohydrate content if the product contains 5 grams of fiber or more. This technique is often used by diabetics who take insulin. Many food manufacturers subtract the fiber content from the total carbohydrates even if the amount of fiber is as few as 1 to 2 grams. Don’t make the same mistake!

• Sugar alcohol. If the product contains sugar alcohol, you can subtract half the grams of sugar alcohol from the total carbohydrate content.

• Glycerol or glycerine. If the product contains glycerol or glycerine, you need to include those grams in the total carbohydrate content.

When planning your diet, keep good nutrition in mind rather than just focusing on calories, fats, or carbs. Think balance, variety, and moderation! A healthy diet is one that incorporates foods from the following groups:

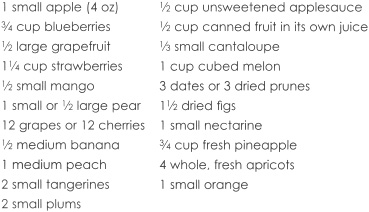

Fruits and vegetables. Most fruits and vegetables are low in fat and are loaded with vitamins, minerals, fiber, and disease-fighting phytochemicals. Vegetables are low in calories and are a great way to fill yourself up. Aim for a minimum of 1½ cups of vegetables a day. Although fruit contains a moderate amount of calories and carbs, you can include 1 to 2 servings a day into your diet. See below for serving sizes and nutritional content of some fruits. We recommend that you select fruits with a lower glycemic index (or load).

Fruits: Each serving has approximately 60 calories and 15 grams of carbs.

Starches and whole grains. Whole grains provide essential vitamins, minerals, antioxidants, fiber, and phytochemicals. The trouble is trying to figure out what is a whole grain and what’s not. Look for a whole or whole grain before the grain’s name in the ingredient list on the food label. For example, choose whole grain wheat bread over white or “wheat” bread. Products labeled as multigrain, stone-ground, seven-grain, pumpernickel, or organic may actually contain little or no whole grains. Examples of whole grains include whole wheat, whole barley, whole oats, bulgur, quinoa, Kamut, spelt, buckwheat, wheat berries, and amaranth. You can also look for a “whole grain” claim on other parts of the package’s label. For qualifying foods, the federal government has approved a health claim that recognizes the health benefits associated with diets rich in whole grains. This claim makes it easier for you to identify foods that are rich in whole grains. The health claim states:

Diets rich in whole grain foods, and other plant foods and low in total fat, saturated fat, and cholesterol, may help reduce the risk of heart disease and certain cancers.

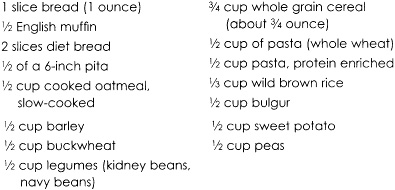

Even if you are following a low-carb diet, you can still fit several servings of whole grains into your diet. See below for serving sizes and nutritional content of starches.

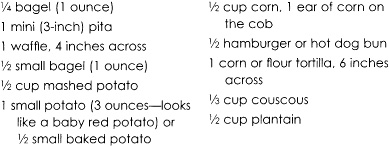

Starches: Each serving has approximately 80 calories and 15 grams of carbs.

Low to moderate glycemic index choices—recommended: The following breads should be whole or whole grain.

Higher glycemic index choices—consume less frequently:

Any of the above bread choices that are not whole grain (“wheat,” white, semolina).

Although I do not forbid any foods, I recommend that you select whole grains or lower glycemic foods as often as possible.

Calcium-rich foods. Only one-half of Americans get the calcium they need. You need adequate calcium to strengthen your bones and decrease the risk of osteoporosis. Calcium can also help lower your blood pressure and may play a role in preventing colon cancer. In addition, new research suggests that low-fat dairy products play a role in burning fat. Aim for 1,000-1,500 mg of calcium a day. If you cannot meet your needs with food, take a calcium supplement. Calcium-fortified products vary, so make a habit of reading food labels for calcium content.

Here are some calcium-rich food sources:

8 ounces milk (1% or nonfat) = 300 mg

8 ounces yogurt (nonfat or low fat) = 350 to 400 mg

1 ounce cheese = 200 mg

Canned sardines, 3 ounces, with the bones = 375 mg

Canned salmon with the bones = 170 mg

Leafy greens, ½ cup = 100 to 150 mg

Protein. Protein is an important component of every cell in the body. Your body uses protein to build and repair tissues and to make enzymes, hormones, and other body chemicals. Eating adequate protein at meals and snacks can increase feelings of fullness and decrease hunger in between meals. Try to select lean rather than high-fat sources of animal protein.

• Very Lean and Lean Protein Foods contain 30 to 55 calories per ounce and 0 to 3 grams of fat per ounce.

Skinless poultry

All fish and shellfish

Beef: USDA Select or Choice grades of beef trimmed of fat, such as round, sirloin, flank, tenderloin, and ground round

Pork: fresh ham, boiled ham, Canadian bacon, tenderloin, center loin chop

Lamb: roast, chop, leg

Veal: lean chop, roast

Cheese: cottage cheese, nonfat or 1%, ¼ cup; grated Parmesan cheese, 2 tablespoons; fat-free cheese or cheese with less than 3 grams of fat per ounce

• Medium-Fat and High-Fat Proteins contain 75 to 100 calories per ounce and 5 to 8 grams of fat per ounce.

Beef: most beef products, including ground beef, meat loaf, corned beef, short ribs, and Prime grades of meat such as prime ribs

Pork: top loin, chop, spareribs, ground pork, pork sausage

Lamb: rib roast, ground

Veal: cutlet (ground or cubed)

Poultry: dark meat with skin, or fried chicken

Cheese: regular cheeses such as American, Swiss, and cheddar have 100 calories per ounce; cheeses such as feta and part-skim mozzarella have 70 calories per ounce

Others: eggs, sausage, salami, hot dogs, bacon, knockwurst

Nut butters: 1 tablespoon

Tofu, 4 ounces or ½ cup

Despite being higher in calories and total fat than some other protein foods, nut butters and tofu contain more unsaturated than saturated fat. They also have many health benefits.

Fats. Not all fats are created equal! The type of fat you consume is more important than the amount of fat. Certain types of fat can damage your health, whereas others offer health benefits. Keep in mind that while some fats are more healthful than others, they all have about the same amount of calories. Your fat cells do not know the difference between “good” or “bad”! Therefore, it is best to consume all fats in moderation to help control your caloric intake.

Limit These fats:

• Saturated fats are found in foods that come from animals, including whole milk and products made from whole milk (ice cream, cheese, butter, sour cream, etc.), chicken skin, and high-fat cuts of red meat. Some plant-derived foods, such as coconut and palm oil, also contain saturated fat. All these saturated fats can raise LDL (“bad”) cholesterol. Since women with PCOS frequently have an abnormally high fat content in their blood, it makes sense to limit your intake of these fats.

• Trans or hydrogenated fats: Hydrogenated fats are found in stick margarine and shortening, some soft tub margarines, many processed foods, snack foods (including potato chips), cookies, crackers, commercial baked desserts, and fried fast foods. Hydrogenated fats contain trans fatty acids (TFAs) that act much like saturated fats in that they can raise LDL cholesterol. In addition, they can decrease HDL (“good”) cholesterol. Manufacturers don’t advertise the presence of these fats, so check the ingredient list for the words hydrogenated fat and avoid products containing trans fats as much as possible

Select Healthy Fats:

• Monounsaturated fats are found in olive oil, rapeseed oil, many nuts and nut butters, and avocados. These fats, when substituted for saturated fats and TFAs, can help to decrease your risk of heart disease. I recommend nuts and nut butters as part of meals and snacks—assuming you can control the portions!

• Omega-3 fats are found in fatty fish, including salmon, tuna, mackerel, trout, and sardines, as well as in flaxseeds, canola oil, and walnuts. Omega-3 fats have anti-clotting properties and anticlotting effects, which protect the heart and may suppress tumor growth. Try to include fatty fish (as well as all kinds of fish!) in your diet at least three times a week.

As well as eating PCOS-friendly foods, your long-term healthful lifestyle plans should take into account what works best for you, physically and emotionally. What has worked best for you in the past is likely to do so in the future. The same is true for trouble spots. What caused problems for you in the past is likely to trip you up again! You have a history that you need to consider in order to make a plan that’s going to work.

Every medical student learns that the first step in assessing a new patient’s health is taking a personal history. Yet when it comes to dieting and weight control, personal history is often entirely ignored. This problem has unknowingly led millions of dieters to failure, as the same people gain back the same weight with the same foods again and again.

Anyone who has ever tried losing weight has been taught that they need to burn more calories than they take in. Or that they need to count the grams of fat or carbohydrates in the foods they eat. Yet it’s this emphasis on calorie and carbohydrate counting alone that has led millions of dieters to failure. The single most powerful strategy of winners at weight control is taking their food history into account.

Thinking calorically (about the calories alone) puts the focus squarely on food and how it functions in the body. Thinking historically shifts the focus to you—how you have behaved toward food, and your unique history (or eating print) with a food or group of foods. When you stop thinking calorically and start thinking historically, you shift your focus to the most critical element for success at weight control: you.

Two people may react very differently to the same food. For one person, a single dinner roll may be very satisfying, especially if that person has no history of abusing bread. Another person might only have to take a bite of that very same roll for it to unleash a torrent of cravings that will cause her to consume the entire bread basket. Or she might find herself thinking more and more about bread, which could lead to ever greater quantities consumed at subsequent meals. Knowing which is true for you could mean the success or failure of your weight loss plan. Ultimately, it doesn’t matter whether a roll has 200 or 300 calories. When you take a hard look at your history with a food, not just how many calories it contains, you change your thinking about it. Do you have a long history of abusing bread and bread products? Does even a taste lead to you eating thousands of calories’ worth a short time later?

Thinking historically, not just calorically, is the first and most critical strategy for success at weight loss and, more importantly, long-term weight control. Once you start thinking about a food or group of foods in terms of your individual history with that food, your perception changes. You’ll look at that harmless little roll and it will take on a whole new light. Try to think of the foods you have a negative history with in terms of calorie units. That is to say, instead of asking “How many calories?” ask yourself “How many of those do I typically eat at a sitting, based on my history?”

So, you see, when it comes to food, history always trumps calories. When people fail in dieting, it often has nothing to do with the particular plan, or their motivation. They fail because they include foods in their diet that they have a long history of abusing. Much has been made in the popular media of the benefits of eating whole grain products. That’s fine if you have no history of abusing grain products. However, if your history says otherwise, then you’re just setting yourself up for trouble.

It’s been said that predictability is the highest goal of science, and I’m going to argue that knowing your own unique history with food is the most scientific approach to weight loss. Your food history does the following:

• It predicts in advance how you’ll behave with any food.

• It predicts the time of day when you’re most vulnerable and likely to lose control or overeat.

• It helps you evaluate food not just in terms of caloric intake and caloric release, but in terms of how it affects your behavior, mood, appetite and, ultimately, your success at dieting.

• It predicts the situations that you most often associate with out-of-control eating.

• It establishes guidelines and helps you set boundaries that don’t come from some “one size fits all” approach to dieting, but from your own eating prints.

• It changes your thinking from “I’m good or I’m bad” to “What does or doesn’t work for me?” Don’t think about the foods the foods you can or can’t have—think about the food that does or doesn’t work for you.

Your eating habits play a major role in how you feel physically and mentally—and, of course, whether you are losing weight. Although your total caloric intake is the most important factor when it comes to weight control, there are other factors that are important as well. The times you eat, the composition of your meals, and the kind of carbohydrates you are eating all play a role in your weight, mood, energy levels, and health. Before you start to work on your eating plan, it’s important that you get a really good idea of what your eating habits are like and establish which areas you need to work on. I’m going to guess that right about now you’re saying to yourself that you already know where your problem areas are. That you know how many calories you eat in a day. But have you kept a food journal? Have you weighed or measured your portions? Studies have shown that most people vastly underestimate the amount of food they eat. It is time to get out the measuring cups, spoons, and food scale.

Make a commitment to keep a food record for at least a week. Try the food diary format below. Feel free to make changes, and keep your diary in a notebook or online, whichever is easiest for you.

As you can see, there’s space to enter information about the following points.

• Time of day you eat

• What you eat, including portion size. Use a measuring cup for grains such as cereal, rice, and pasta (cooked), and a measuring spoon for oil, salad dressing, and peanut butter. Use a food scale for meat, fish, poultry, cheese, nuts, and dry pasta.

• Where you are when you eat. Certain places can trigger eating.

• Any emotion you feel before or while you’re eating. Eating in response to emotions is a major cause of overeating for many of us.

• Degree of hunger. Before you eat, rate how hungry you are on a scale of 0 to 10, where 10 is famished and 0 is not hungry at all. A 5 is neutral: neither hungry nor not hungry.

• Record calories, if you wish.

Once you have kept your food record for a week or so, ask yourself these questions.

TIMING QUESTIONS

What times of the day do you normally eat?

Do you let more than four hours go between meals or snacks?

Do you generally plan a snack for the middle of the afternoon?

Do you skip meals?

PORTION CONTROL QUESTIONS

Did any of your portions surprise you?

Which foods do you tend to overeat?

COMPOSITION OF MEALS QUESTIONS

Are you including an adequate source of protein and fat at meals? (For example, do you try to make a meal of a salad with just veggies and fat-free dressing?)

Are you selecting whole grains or refined grains? (For example, whole wheat bread or white bread? Brown rice or white rice?)

Are you eating at least three servings of vegetables a day? One or two fruits? Two servings of dairy products?

Do certain foods cause increased cravings? If so, which foods?

Do you experience fatigue or increased cravings after eating high-carbohydrate meals?

Which snacks are most satisfying and help control your hunger?

Which snacks leave you wanting more?

Which kinds of meals or snacks make you feel better: higher protein or higher carb? For example, a high-carb meal like cereal, milk, and fruit or a high-protein omelet? Pretzels (high carb) or small handful of nuts (high protein)?

Think about what these questions reveal to you. Do you go for long stretches of time without eating? Do certain foods make you feel better than others? Do certain foods trigger you to eat more? Do you find that certain emotions frequently drive you to eat? Keep these thoughts in mind as you read on.

Studies have shown that women are now eating 335 more calories per day than they did in 1971, increasing their total caloric intake from 1,540 to 1,875 calories a day, with 40 percent of those calories eaten outside the home. That percentage seems low to me. Most of us have hectic schedules and tend to grab food on the run—a bagel or a muffin for breakfast, a deli sandwich for lunch, perhaps an afternoon snack from the vending machine. If you don’t have time to cook dinner, it could be take-out pizza, Chinese food, or a “home-cooked” frozen meal. If you are following a low-carb diet, you may well be consuming too many calories from protein and fat, or maybe, like so many others, you’ve simply gotten into the habit of eating more calorie-laden foods of all kinds. Bottom line: All calories count, wherever you happen to eat them.

Whether you plan on counting calories, it is still a good idea to have an estimate of what your body needs to maintain your present weight and perhaps more importantly the changes you’ll need to make to lose weight. Your caloric needs will vary depending upon several factors, including activity level, age, sex, weight, body composition, and individual metabolism. Many online caloric need calculators are available, such as at www.calorie control.org/calcalcs.html or www.active.com. Keep in mind that many online caloric calculators overestimate the caloric needs of obese women.

Here is a quick method for estimating your caloric needs.

FOR WEIGHT MAINTENANCE

10 calories per pound for women who are obese, very inactive, or chronic dieters

13 calories per pound for women over age fifty-five who are very active or moderately active women under the age of fifty-five

15 calories per pound for very active women under the age of fifty-five

If you tend to have a difficult time losing weight and are obese, very inactive, or a chronic dieter, it is possible that you may need to reduce your intake to 8 or 9 calories per pound.

FOR WEIGHT LOSS

To lose 1 pound a week, subtract 500 calories from maintenance caloric level

To lose 2 pounds a week, subtract 1,000 calories from maintenance calorie level

Thirty years old, 5 foot 5, and 160 pounds, Sue exercised three times a week for forty-five minutes. She had been “dieting” for many years, but the gains pretty much cancelled out the losses. To find her caloric needs for weight maintenance, Sue multiplied her weight by 12 (since was moderately active, yet a chronic dieter). Her weight maintenance caloric needs were approximately 1,920 calories a day. To lose a pound a week (subtract 500 calories), she needed to consume 1,420 calories a day. To lose one and a half pounds a week (subtract 750 calories), she needed to consume 1,170 calories.

Keep in mind that these are just calculations and they do not take your individual metabolism into account. Many overweight, insulin-resistant women with PCOS do not lose weight according to the preceding calculations. If you have been unable to lose weight on a low-fat or moderately low-carb, calorie-controlled diet, try the accelerated weight loss eating plans in this program. They average 1,100 calories a day, with approximately 35 percent of the calories coming from carbs.

To lose weight, you need to consume fewer calories than you burn. Many of the popular diet plans focus on restricting fat or carbs—perhaps to distract you from the fact that they’re also reduced-calorie diets! As discussed, your body needs a certain amount of calories in order to maintain your current weight. If you eat fewer calories, you lose weight. If you can’t limit your calories to a point below maintenance, you won’t. It does not matter where the calories come from—excessive calories from protein, fat, or carbs will all stymie your weight loss goals.

Betty, who had PCOS, was insulin resistant and a chronic dieter. She had been following a very low carb diet for twelve weeks, had lost four pounds initially, but had been unable to lose any more weight. In fact, she gained two pounds back. She had frequent headaches and minimal energy, and soon she was making only two trips to the gym per week instead of her usual four.

Betty’s breakfast consisted of two eggs, her midmorning snack was 2 ounces of cheese, and her lunch from a diner was a large burger (7 ounces, no roll). For an afternoon snack she grabbed a protein bar or a large, low-carb cookie and often ate a few ounces of cold cuts while making dinner—8 ounces of chicken, or fish and a cup of veggies with a tablespoon of oil. A few handfuls (2 ounces) of nuts made up her after-dinner snack. Betty’s diet totaled approximately 2,200 calories. At a weight of 160 pounds with moderate activity, Betty only needed about 1,900 calories to maintain her weight and 1,400 calories to promote a one pound loss a week. The numbers, obviously, weren’t working in her favor! While she’d successfully cut back on carbs, she’d unwittingly put herself on a diet guaranteed to result in a slow but steady weight gain! She was consuming an excessive amount of calories in the form of protein and fat. Too few carbs in her diet led to headaches, low energy levels, and fewer trips to the gym.

To help Betty lose weight, we cut her calories to a more balanced 1,400 a day. We cut down on her portion sizes of protein and fat, and added in some low glycemic index carbs in the form of fruit and whole grains. The changes were as follows:

Breakfast: 3 egg whites made with ½ cup veggies sautéed in 1 teaspoon fat, and 1 slice of whole wheat toast

Midmorning: 1 string cheese and a handful of baby carrots

Lunch: grilled chicken kebab, 5 ounces, with a side of steamed veggies, 1 teaspoon fat

Afternoon snack: 12 almonds and 1 small apple

Dinner: 5 oz of lean protein, 1 tablespoon oil, 1½ cups veggies, and ½ cup brown rice

Snack after dinner: 1 cup of berries with 2 tablespoons sugar-free whipped cream

Betty reported that her energy levels improved and her headaches disappeared. She went back to exercising four days a week and lost four pounds over the next month.

Some of you may be wondering why Betty initially lost four pounds and then regained two. Her initial weight loss on the scale was due to a loss of water. It is not unusual to lose several pounds in the first week of low-carb dieting. Here’s how it works: Your body stores carbs in the form of glycogen to use for energy. Glycogen is stored in association with water. When you decrease your intake of carbs, your body uses the stored glycogen for energy. As the stored carbs are being burned, your body releases the water stored with it. This is why you probably find yourself running to the bathroom frequently when first starting a low-carb diet! It is not unusual to lose three pounds or more of water in the first week of following a low-carb diet, but ultimately, it’s calories that count. To lose one pound of fat, you must create a deficit of 3,500 calories. In Betty’s case, she did not have a caloric deficit. On the contrary, she was consuming more calories than her body needed. After her initial water weight loss, I would not have expected her to lose weight. Fortunately, the fix was a simple one: By cutting her caloric intake down to 1,400 while maintaining a low glycemic index diet, she was able to lose about a pound a week. This was mainly from loss of body fat—not a water loss.

Here are some tips to help you become aware of your caloric intake.

On occasion, weigh and measure some foods. Do you know what one cup of pasta looks like? You would probably be surprised at how small it is. Do you know that an average restaurant-sized serving of pasta is 3 to 4 cups? That is 600 calories—before the sauce is added! Do you know that an average-size bagel (4 to 5 ounces) is equivalent to eating four to five slices of bread and has 360 calories?

The next time you slice off a piece of cheese for a snack, put it on your food scale first. Full-fat cheese is approximately 100 calories an ounce, whereas low-fat cheese ranges from 50 to 70 calories an ounce. And who eats just an ounce?

Measure or weigh your cold cereal. Most of us eat a larger serving size than what is listed on the label. It is not uncommon to eat a 300-calorie bowl of cereal (and that does not include the milk and fruit on top).

Is steak and a salad your idea of a “dieter’s delight” in a restaurant? Think again—a 12-ounce Prime cut of steak can easily have 1,200 calories and 96 grams of fat, while the salad with blue cheese dressing (2 tablespoons) has 190 calories and 18 grams of fat. This is a grand total of 1,390 calories and 114 grams of fat!

Many chain restaurants list the nutritional content of their menu selections on their Web sites. Check to see if the restaurants you frequent have Web sites.

You do not have to feel deprived when trying to lose weight. These calorie-smart options can help fill you up while keeping your caloric intake on the low side:

• 6 ounces cooked shrimp (12 large) have 168 calories. Delicious and filling!

• 6 ounces cooked scallops have 175 calories. Try broiling them with lemon or cooking them in a nonstick pan with mushrooms and wine.

• 6 ounces skinless turkey breast has 180 calories.

• An egg white omelet made with 4 egg whites and 1 cup of veggies in a nonstick skillet only has 110 calories. Add flavor with a little hot sauce or salsa.

• Homemade vegetable soup made with low-fat chicken broth (low-sodium, if desired) and your favorite low-starch vegetables is a low-cal winner; 2 cups are only 50 calories or so. Read the labels for the nutrition content of commercial soups. Studies have shown that soup eaten before or as part of a meal can help to promote weight loss. Soup helps fill you up, as well as slow down the rate of eating.

• Vegetables—raw or cooked—are low-calorie winners. For variety, try them grilled, roasted, or stir-fried (see next chapter for recipes); 1½ cups of vegetables are 100 calories or less.

CALORIC CONTENT OF SOME POPULAR FOODS

1 slice of pizza: 450 calories

Deli tuna salad sandwich: up to 730 calories

Caesar salad: 400 to 600 calories (more for entrée size)

General Tso’s or kung pao chicken: over 1,500 calories and 60 grams of fat

Mood eating is about immediately replacing an unpleasant feeling with a pleasurable one. Much research has been done on the relationship between food and mood—for instance, on the connection between eating carbs and brain levels of the mood-enhancing neurotransmitter serotonin. Carbs may be responsible for the spike, but unfortunately the effects last for less than thirty seconds, and you then need to eat more carbs!

Mood eating is a vexing problem for dieters. It’s also one of the more challenging issues to deal with because so many of the “one size fits all” diets on the market today have a few or no answers for people with a history of this condition. Diets that follow the calories-in-calories-out approach to weight loss often lose sight of the person—the key factor in any weight loss equation. In addition, mood eating is often intensified in women with PCOS because the emotional stress brought on by physical and metabolic changes often stirs up feelings of anxiety, fear, and frustration. Along with changes in their physical appearance and metabolism, women with PCOS are at increased risk for reproductive problems, including infertility, miscarriage, and diseases such as type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and uterine cancer. So it’s no surprise that, taken together, these physical and emotional stresses can intensify the symptoms of PCOS.

If you have PCOS, you may find mood eating is most often triggered by day-to-day annoyances such as an argument with your spouse or getting stuck in traffic. These problems may simply seem magnified because of your condition. It’s important to recognize that the type of stress that causes a person to mood eat is predictable—it often arises from the same situations such as interactions with an irritating coworker.

For most of us, mood eating is not about food in and of itself. It’s almost always about snacking or grabbing on whatever food happens to be within arm’s reach, particularly snack foods and simple carbohydrates such as pretzels, potato chips, and chocolate. For a lesser number, it’s about a different type of snack food, such as ice cream.

What characterizes eating as mood eating?

• Same food. Are you returning again and again to your favorite snack foods? Mood eaters rarely react to stress or disappointment by food shopping or cooking a gourmet meal. Mood is about snacking on what’s easiest to get in your mouth.

• Same place. Are you eating alone in your kitchen? Most mood eating takes place in the kitchen. A small number of mood eaters do their eating at work. The availability of snack foods in your home creates cravings, and the variety stimulates consumption.

• Same time of day. Are you snacking in the late afternoon or evening? Mood eating usually takes place at these times, and rarely occurs in the morning.

• Same moods. Are you eating because you feel anxious, bored, angry, betrayed, or frustrated? These feelings, which are common in women with PCOS, often trigger mood eating.

• Same people. Are certain people triggering your mood eating? The same people stress out mood eaters again and again. For PCOS patients, it could even be people who are trying to be supportive of your condition, such as a doctor, parent, spouse, or friend.

• Same situations. Are you snacking in response to certain situations? Mood eaters snack because the same situations stress them out again and again. Perhaps you reach for a snack before you visit the doctor, or, if you’re trying to conceive, before you take a pregnancy test.

• Same quantities of food. Are you choosing snacks that enable you to drag out the eating experience, such as pretzels or a bag of M&M’s? Mood eaters want the eating—the source of comfort—to last as long as possible.

• Same reason. Are the foods you’re choosing providing you with a sense of comfort, or do you view them as a reward or treat? If you’re distressed over your condition, you may turn to a favorite snack to allay your feelings, or decide to “treat” yourself if you’ve had a particularly difficult or stressful week.

The most immediate reason a person uses a food to change her mood is because it tastes really good. Mood eaters usually choose foods with a creamy or crunchy texture that’s either sweet or salty. These tastes and textures provide the person with immediate gratification, in much the same way that exercising vigorously or talking with a friend about a personal problem can release pent-up feelings or emotions. If you keep a lot of snack foods around your house, eating to vent your emotions becomes markedly easier.

There’s no denying that the foods most mood eaters choose have a pleasing taste. However, the pleasure derived from food is fleeting, and most mood eaters end up regretting it later. On the bright side, since mood eating is a learned behavior, it can just as easily be unlearned and corrected through strategy.

Contrary to what you might think, the best place to end mood eating is not your therapist’s office. It’s the supermarket! Since mood eating often occurs in the kitchen and with foods you bring into the house, don’t buy the snacks you tend to abuse when you’re anxious or stressed. Even the most hardened mood eater will resort to another activity, such as reading or watching TV, if the snacks are not immediately accessible. Think about it. Are you really going to break the habit of snacking on potato chips or pretzels if there’s a supply in your kitchen pantry?

Snacks that won’t make you fat include cut-up green vegetables, apples, individually wrapped low-fat cheeses, chilled beverages such as flavored water or diet lemonade, sugar-free gum, single-serving bags of unsalted sunflower seeds, and bran crackers (especially GG Scandinavian Crisp bread crackers, which are great for killing appetite). You may also want to keep some low-calorie substitutes for your favorite foods on hand, such as an individually wrapped bag of Knight’s lite popcorn, a Weight Watchers chocolate mousse pop, or a Van’s 7-Grain Belgian Waffle.

Sometimes the availability of a favorite snack food creates a rationalization to eat it. The single best strategy to end mood eating is to throw out all the mood snacks in your home. The next time you go shopping, make a list and keep your mood snacks off it. If you live with someone and must keep snack foods around, especially those that tempt you or trigger cravings, buy only those snacks that come in single servings and hand them over to the person who wanted them as you’re unloading the groceries.

• Keep an ample supply of snacks available that won’t make you fat. If you’re craving chocolate, you may find that one chocolate mousse pop leaves you satisfied. Remember to consider your history before you make a decision. If you feel that the waffle may stimulate cravings for baked goods, this may not be the best choice for you.

• Keep all snack foods out of sight.

• Ask family members not to snack in front of you.

• Have someone hide tempting snacks.

• If nothing else works, lock the most enticing snacks, except for the ones that are perishable, in a cash box. It may sound a little draconian, but it works. Remember: Availability creates cravings.

• Make a list of healthy, low-calorie snacks and shop for them. Banish things you have a history of problems with.

• Recognize trouble before it happens. If you have a weakness for french fries, don’t drive by a McDonald’s on a day when you expect to be under stress.

• Rehearse a stressful situation or event you expect to encounter. Many mood eaters find it helpful to mentally prepare for a stressful situation. For instance, you can practice what you’re going to say to someone you’re anxious about confronting, or visualize yourself breezing through a situation you dread, such as a visit to the doctor’s office.

• Block that mood. The winners at weight control don’t let the unknown catch them off-guard. Planning is stronger than willpower—this is a motto that all former mood eaters live by. Stress doesn’t have to convert to body fat. One of the best strategies to end mood eating is talking on the telephone. It’s the quickest and most effective way to end mood eating immediately. So call someone you enjoy talking to, such as a friend or colleague. You don’t even have to tell the person why you’re calling. Talking on the phone diverts your mind and will help relax you. It’s a great blocking behavior. You may even find that by the time you finish your conversation, the compulsive need to overeat has passed.

There’s much confusion about the difference between pleasure and happiness. Any pleasurable feeling you derive from food is transient. In fact, the pleasure you derive from a cookie or a bag of potato chips may actually destroy the possibility of lasting happiness. Even if you’re feeling anxious or stressed, or are depressed about having PCOS, you’re going to feel much better about yourself if you consistently make decisions about eating that will help you take control of your weight.

Any pain in your life that has resulted from PCOS will only be aggravated if the foods you have turned to for comfort have done little except cause you to gain weight. If you reach for food every time you to feel frustrated or angry over having PCOS, you’ll be even more upset the next time you step on the scale or look in the mirror. The great irony of mood eating is that we eat because something has upset or frustrated us and then we get even angrier after we abuse food because of it.

Every time you use food as a crutch or eat in response to a stressful event, person, or situation, you perpetuate in your own psyche the very real sense of being unable to cope without food. It doesn’t have to be that way. PCOS is not a life sentence. Adopting the strategies in this chapter and the eating plan in the next can help you from turning to food the next time you feel out of control or despondent about your condition. Having a plan puts you in the driver’s seat, and there’s no greater feeling in the world.