Communication Operations

One of the primary defensive functions of bases dotted along the SWA/Angola Border was known as ‘Communications Operations’ (Comm Ops).

The purpose of Comm Ops was to engage remote indigenous (First Nation) peoples across a vast swathe of the border region. These were mostly people of the Owambo tribe (pronounced Oh-vum-boh), a semi-nomadic group of hunter-gatherers who in their recent history, like say the past few thousand years or so, had begun settling in tiny clusters or homesteads.

Typically, an Owambo homestead consisted of a large kraal – round dwelling built only from sticks set upon a covering of hardened cow-dung floor tamped down over many years by the incessant movement of thorn-hardened bare feet. The main kraal was normally surrounded by an inner perimeter fence, also sticks bound together with bark or strips of animal-hide, and then an outer perimeter fence surrounding the entire homestead consisting about half-a-dozen smaller, less important kraals. This ingenious layout of the homestead offered a sort of layer-cake security arrangement – like a prehistoric Pentagon or Camp Bastion – but dating back to a time when a quarry of rocks and rudimentary spears were the only weapons of mass destruction known to man.

Participating in the trooping of the colour at the Corp’s 40-year anniversary parade the previous year had been a grand affair, attended by some of the biggest cheese the army could muster. We’d practised drills endlessly and when we marched past the TV cameras, 40 deep, in perfect alignment, it had been with a genuine sense of pride that we represented School of Armour at such an auspicious event; there was maybe even 15 nanoseconds of fame as they filmed our march past and the ‘eyes-right’ saluting big cheese.

On Township patrols, I was able to see at first-hand the plight of some black South Africans. Although we didn’t move among residents of the Township much on foot, the experience was a somewhat humbling, seeing how these people lived.

Comm Ops on the other hand offered an opportunity to engage Owambo tribes people personally, individually. The month-long operation was more like a journey back in human history, back to a time when day-to-day survival really was the only way of life, and people were happy with just the basic necessities such as food, shelter and a sense of belonging. I was quite unprepared for the warmth of their welcome and unencumbered simplicity of their Bushmen lives.

Charlie Squad, with Cpt. Cloete now riding in Three-Zero (30) – the command vehicle – usually set up temporary base (TB) in the middle of nowhere. Each of the three Troops, Three One (31), Three Two (32) & Three Three (33) were designated co-ordinates for specific daytime patrols. Our orders; to make contact with the locals, gather intelligence on suspected terrorist (PLAN) movements, sightings or activity, and try to spread some goodwill among the people.

This wasn’t a risk free enterprise, about the same time two soldiers from another border unit got ambushed by PLAN operatives skulking in the dark shadows of an Owambo kraal. As they bent to enter the cool dark shelter the enemy fighters opened fire on them. Sadly those two soldiers died at the scene.

Their comrades on over-watch delivered a similar ending to the terrorists who had intimidated the homestead’s inhabitants to provide shelter during the patrol’s approach.

Each Troop of four vehicles (e.g. 33, 33A, 33B, 33C) set off into their designated patrol territories. There were no roads or road-signs; this was map-n-compass navigation, so we were never quite certain what we might find each day.

When spotting a distant homestead we’d make a steady non-threatening approach then, with help of an interpreter, request permission to meet with the head of the settlement.

These old-school Africans, who trace their heritage back 10,000 years, knew why we were there, they’d seen this all before, their barren land had become a crossing-over place for SWAPO’s armed forces during their long struggle to ‘liberate’ Namibia.

The Owambo people had no interest in politics or power struggles, their precarious struggle for survival was the pressing issue that dominated their lives. Despite their constant struggle, we normally found them very generous hosts.

Our arrival usually created a bit of a stir in the timeless homesteads, kids running out to greet us, a few wizened heads slowly popping up out the shade of kraals, or a cattle herder pausing in his work.

Normally, the head of homestead would invite us to the main kraal where we’d sit in a circle to talk, share pleasantries and pass round the ubiquitous jam jar of honey-coloured home brew.

It was like we’d been transported back in time, perhaps a thousand years or more, with the notable exception of the machined glass jam-jar. It wasn’t difficult to admire these simple human beings. The ebb and flow of their lives was totally dominated by the passage of the seasons, health of that year’s harvest and, the family trust fund, their tiny herd of malnourished tick-riddled but hardy cattle.

These prehistoric people knew they were sandwiched in a power struggle between people from the north and people from the south and this meant their simple existence was occasionally interrupted by men from the north carrying AK47s moving southwards stealing cattle to feed themselves, and us white boys (and some black boys) coming up from the south and asking for help to track and identify so called ‘terrorists’.

It was impossible to be certain what those Owambo grandees thought of us or if they took sides in the conflict, their concept of modern government and pencil politics almost non-existent. What they hoped for was stability and lots of rain.

What mattered most to us was whether they were harbouring, or could identify, anyone who posed a credible threat.

Whatever the Owambo’s true allegiance in the cross-border conflagration, their hospitality was usually first class and sometimes extremely generous. Jam-jars filled with cool sweet Mohungu juice (a beer derived from a local fruit) were passed round the circle and readily refilled.

While we attended bush diplomacy, other Troopers maintained watch from our vehicles, but inside the kraal politeness dictated we drink at least a little of the amber nectar.

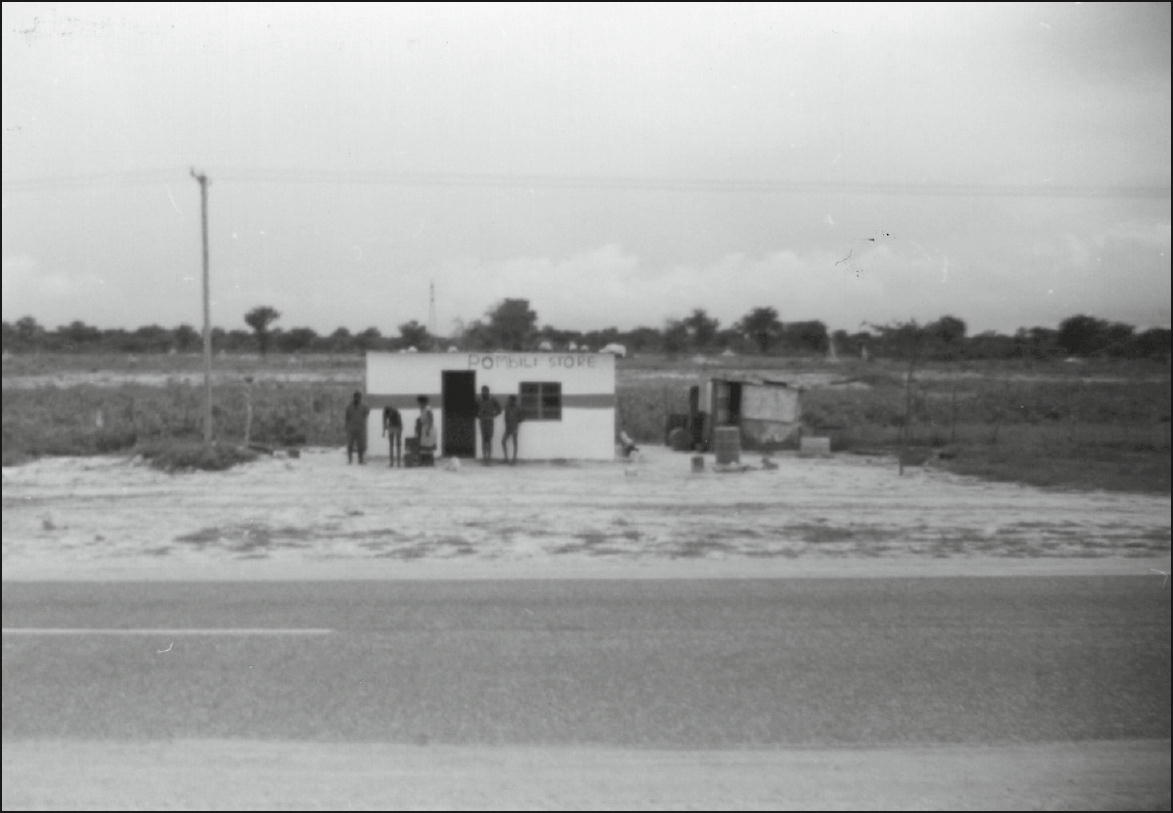

The Mohungu juice (beer) actually turned out to be some pretty good stuff, so we’d regularly find reasons in the early evening, during Comm Ops, to visit local Kuka shops (informal bottle store or off-licence) to ‘improve relations between SADF and locals.’ Cloete would’ve been mildly incandescent had he known, but perhaps we’d have been a little less chilled if we’d been told of the two guys who got killed. Again, there was always this pervasive sense that ‘ … it couldn’t happen to me’.

Part of our early evening goodwill mission normally involved developing informal trade agreements with which to procure a few litres of the chilled sweet-tasting, mind-mellowing brew, at 20 cents a jar (litre). A litre was enough to get a man relaxed and slurring, two litres and he would struggle to walk straight, it was that good.

On one such occasion while on the Juice, the naughtiest of our three Lootys, Bremer, decided to ask one of his crewmen to test the handbrake-turn capabilities of the 7-metre long, six-wheel Ratel out on the smooth flats of a salt pan. That obviously ended badly so he endured a shit-storm after his driver Dries Rheeder rolled his 18-tonne beast onto its side; very lucky there were only minor injuries, perhaps a broken bone here and there.

Photo 12 Time for fun on Comm-ops, Owamboland, an hour after this photo was captured, the vehicle on the right lay stranded on its side after rolling during handbrake-turn training (unsanctioned of course). (Martin Bremer)

Photo 13 Owambo homestead. (Barry Taylor)

Drunken exploits aside, we fortunately never came under attack during Comm-Ops, but one particular homestead visit resonated with me more than any other. It was early afternoon on a typically hot day in the desert, so it was quite a relief to get out of the scorching heat. Our well-practised routine saw me lead a small delegation of Troop Two into the cool, dark kraal.

The matriarch, clearly head of this settlement, invited us to sit with her and a few elders. Soon, with the assistance of my interpreter she confirmed they’d not seen anything untoward in recent weeks, and so the conversation drifted to other things, such as the health of their cattle and the lack of rain.

Conversation continued for about 20 minutes, jam-jar doing the rounds, when the matriarch said something to the interpreter, looked at me and then laughed!

Eager to be let in on the joke I turned to the interpreter who leaned toward me in all seriousness and whispered that the matriarch had just offered me her daughter’s hand in marriage!

Photo 14 Kuka shop in Owamboland. (Barry Taylor)

Her daughter, sitting alongside her, was probably no more than 15 years old – it’s not unfair to say the Owambo people were more relaxed on ‘age of consent’ than most Western societies. We’d not be raised to consider black Africans attractive, nonetheless it was pleasing to be considered suitable marriage material by the matriarch although, considering the competition, I didn’t let it go to my head.

Interestingly, Owambo people weren’t in the least bit concerned by clothing conventions demanded by ‘advanced’ societies in the West and ultra-strict Middle East so fixated on religiosity and the appeasement of a God who designed us naked and then changed his mind and demanded we cover it all up. Fortunately for Owambo people, their men had somehow not got that memo, or perhaps they were not quite so insecure their womenfolk would dash off into the desert with a rival goat herder, so here, ladies covered only baby-making equipment and toileting under-carriage. Everything else, on show.

I examined the two topless ladies sitting side-by-side a little more closely. The matriarch and her daughter were at opposite ends of the age and beauty spectrum.

The matriarch was an exhausted breeding machine, her frail body wizened by countless scorching summer days and just as many freezing desert nights, her skin wrinkled and tough like elephant hide. Her breasts, or what remained of them after suckling an unknowable number of children, were the thinnest longest flaps of skin tissue imaginable, so long in fact, that her well-worn elongated nipples easily nestled all the way down in her lap even though she sat bolt upright drinking home brew while chatting with me.

At the other end of the spectrum, her daughter was blessed with the firmest roundest pair of breasts an 18-year-old boy-virgin could imagine.

This was at a time when South Africa was still fully in the grip of a moral crusade banning almost all forms of nudity, the only girls allowed to pose topless for men’s magazines were always the ones who were born with perfect star-shaped nipples (which I’ve never seen in the flesh), so the scene playing out in front of me was quite intriguing and, when combined with the mellowing effects of Mohungu coursing through my veins, the offer of marriage seemed somewhat appealing.

Reaching for the jam-jar, I slugged a mouthful, passed it back toward the matriarch before politely declining the generous breasts, uh, I mean, her generous offer. This was a lust match made in Owamboland and there was no way that I, the great untouched white virgin boy, would get within squeezing distance of this fulsome firm female.

Growing up in SA meant that black girls were never on the menu anyway and for a time it was even illegal to marry a black person, or person from a different ‘race’, but the sweet beer-fuelled irony of that moment didn’t escape me even then … those six weekend passes during the previous year, the hours busting moves on the dance floor, reeking of desperation, downing Western lagers, struggling to muster enough courage just to get a platonic conversation going with some self-obsessed princess were, from my present viewpoint a waste of time. Here, in the middle of the desert with no music or lights, no fancy chit-chat or bullshit, just simple humanity and sincerity, life seemed more complete. This was old-school dating and it seemed a lot less complicated, perhaps when you live on the edge like these folks, all opportunities must be seized. Perhaps I’d even be allowed to maintain a string of wives as long as I had a good herd of scrawny cattle with which to pay for all those ladies.

Through this, and many other experiences on Comm Ops, we gained an abiding admiration for the tribal people of Owamboland, it was impossible not to respect them for their implacable inner strength, indefatigability and a ruggedness gained by surviving a precarious life eked out in one of the harshest, most barren, inhospitable places on earth. I knew then that my admiration for these hardy people would last a lifetime.