Mission Accomplished

The stunning and overwhelming victory on 3 October caught everyone, including our own people, off-guard. No one had expected such a dramatic shift in the balance of power in the Lomba pocket and it raised the spectre of a major shift in tactics by FAPLA, which in turn meant SADF big cheese needed pause to review their strategy.

Would FAPLA send 59th on to join 21st. Would 16th Brigade quickly be brought into theatre, were 66th on the move south, deeper into the pocket?

In our deadly game of chess, we’d taken their castle, and only sacrificed a pawn. It still hurt though.

In fact, I never saw the crewmen of 33 again. O’Connor took the same cassevac flight out of Dodge City leaving me in temporary command of Troop Two.

Two days after the monumental battle, October 5th, a delegation of big cheese was escorted by Troop One to evaluate the battlefield. They were understandably astounded by the scale of destruction we’d caused and the potential value of abandoned equipment, particularly to UNITA who gained six second-hand MBTs (all with only one previous owner, not so lovingly maintained) and the Yanks who scored some new hi-tech toys including the SA-9 and much anticipated SAM-8! Not one, but three of the secret weapon systems including loader, launcher and control vehicle were captured, some damaged. [I’m told the SA-8 missile system was detoured through Tel Aviv, a thank you to the Israeli’s for their continued support, and a fuck you very much to the Yanks who’d pretty much left us high and dry. In fact, while I’m having a moan, fuck you very much too to the Brits, for very much the same reason, we were on the same side of the Cold War but you left us to handle the heat. In their defence, perhaps they knew SADF could handle it, because we did.]

Unsurprisingly, October three battlefield resembled a Russian arms dealer’s online catalogue, everything from MRLs ‘Stalin Organs’ and hand-held rocket systems to BRDM and BMP tracked vehicles bristling with fearsome weaponry.

[The delegation also recovered a 500-year old bell which had been used to signal meal-times and other salient communications to the widely dispersed, often illiterate, soldiers. It’s unlikely many even owned a watch. The bell was date stamped and was obviously liberated from its original designation in the bell-tower of a destroyed Portuguese Roman Catholic church. This later became known as ‘Lomba Bell’, the centrepiece of the Hind Memorial at Johannesburg’s Military Museum commemorating the fallen of 61 Mechanised Battalion Group, a clear sign of the importance of that battle, even for a unit linked to many of the largest operations ever conducted in Angola. The Lomba Bell came to symbolise the scale of defeat suffered by 47th, that their command and control had fled in such disarray, they neither had time to take the Bell nor it seems, would they ever have cause to signal 47th Brigade again. It no longer existed.]

The arsenal of weaponry and materiel destroyed or discarded underscored the achievement on 3 October, and also proved unequivocally how extremely well 47th Brigade had been equipped.

The events of 3 October cost Adrian Hind his life but in the harsh extremes of war, and when contrasted with the comprehensive battering we dealt FAPLA, this was a minor, but nonetheless deeply tragic loss. We, the survivors, acknowledged our good fortune at having lived that momentous day.

I don’t really remember feeling much emotion then. Somehow it was easier to focus on the dangers ahead rather than dwell on the loss of 33. I hadn’t seen Adrian die, nor the extent of Glen’s wounds, and for that reason perhaps they had less of an emotional impact on me, or maybe that’s just the nature of war.

After the guys got back from their battlefield tour we were ordered to prepare for contact the following day, October 6th, this time against elements of 21st Brigade still at the same bridgehead they’d clung to during September.

With O’Connor gone I’d finally get to lead Troop Two in combat, but only if I had a working Ratel.

In the days immediately following that significant battle, Thirty Two Alpha limped behind a monster tow-truck from TB to TB as we moved east back toward 21st Brigade’s bridgehead.

A replacement vehicle was ordered up from god-only-knows-where and promised to be with us in ‘two or three days’, which became increasingly significant when we learned of impending contact on the 6th.

Waiting for our replacement was unbearable, I sincerely did not want the already depleted Squadron to go back into battle without me. We were a unit, a team, a crew and although I knew we weren’t invincible, that battle on 3 October was the most adrenaline-filled, super high imaginable.

I wanted back in, but it wasn’t because I’d morphed from beach-bum-v-lover-boy to some Hollywood ‘Top Gun’ adrenalin junkie; I was bonded to my brothers-in-arms, prepared to stand shoulder to shoulder with them until the very end.

On the night of 5th October, just 12 hours before contact, 32 Alpha’s crew was still without a fighting vehicle. I was constantly pestering Tiffies to get me sorted.

“Ja, Ja ons sal vir jou nuwe voortuig voor die oggend he” (yes, yes, we’ll have a new vehicle for you before the morning).

I felt like asking, “Do you okes not know the pre-battle rituals I have to go through?” Nevertheless, we were quietly impressed they’d managed to call up a reserve vehicle so quickly.

Aside from my own preparatory rituals, there were other, more critical tasks to perform; transferring and mounting the brace of Browning, ‘sighting-in’ the 90mm gun sight and loading a ton of ammo.

The gun sight was a sensitive piece of kit and easily damaged, like Warren Adam’s sight early on at Lomba, so they were designed interchangeable. When newly housed sights require calibration to ensure they point at the same place as the cannon. Normally this involved a trip to the shooting range and a target whose distance is precisely known, ideally 1,000 metres. A good gunner should ‘sight-in’ and require no more than three shots before locking his gun sight in position.

Our overnight hop on 5th October had brought us within relatively close proximity of 21st Brigade meaning Charlie Squadron was enjoying an unusually late start the morning of 6th October.

Unbelievably true to their word, Tiffies rolled in with a replacement Ratel [no call-sign markings, or maybe it had a large 8, I don’t recall] just as the morning sun crested the horizon, but by now it was almost 06:00 and Charlie Squadron was moving out to the staging area a few clicks away.

We parked the new and unfamiliar Ratel next to its beloved predecessor, hurriedly transferring ordinance, radios and gun-sight from one to the other.

By now Charlie Squad was long gone but I wasn’t ready to concede!

Half an hour behind our Squad, with assistance from the mechanics, we were bombed up, mounted up and revved up, tuning the two unfamiliar radio sets behind me in the turret while David Corrie’s inaugural ride on his new steed was directly into battle.

Without satellite navigation, roads or map for guidance, we relied on Charlie’s fresh tyre tracks in powder-soft sand to direct us. I was anxious to close the gap, “Let’s just get there! It’s probably a 20-30 minute drive to the staging area. If we hammer it we can catch up with the squad before the shit goes down.”

David floored it, giving our new Ratel a thorough induction – our radio whip-antennae probably last felt such wind resistance before we came off tarmac roads, five weeks earlier (we’d also transferred antennae from our damaged vehicle).

Turning my attention back to the radios, I tuned the two sets and listened in to familiar pre-battle build-up on Squad net.

Ten minutes later, Cloete ordered Charlie to make a 90 degree right turn and deploy in combat formation facing suspected enemy positions circa 800m into the forest.

Troop Two had been riding the tail of the convoy which when they made the 90 degree turn would place them right front, meaning all I needed to do was look out for the first tracks bearing right, I estimated we were less than 2 or 3 clicks off their position.

After advising Cloete we’d soon be joining them, I radioed Fouche and Robbello the Troop’s remaining crew commanders, advising them to expect us to be dropping in from behind them when Zeelie suddenly piped up “ … maar Korporaal ons het nog nie die 90 sights ingeskiet” (but Corporal we haven’t calibrated our gun sight yet.) “Fuck, more time lost! Herb, you’re gonna have to ‘sight-in’ your gun on the move my man.”

“Nee, Korporaal dit kan nie so gedoen nie.” Which loosely translates as … “No Corporal it can’t be done, you’re nuts!”

Zeelie, by now a battle-hardened accomplished veteran gunner knew as well as I did Ratel 90 is not designed for fire on the move, her gun couldn’t track a target like more modern turrets with in-built electronic ‘stabilisers’.

Without ‘stabs’, the tiniest pitch or yaw when moving was greatly magnified a mile down range, but we didn’t need that degree of accuracy, we weren’t expecting contact at ranges greater than a few hundred metres.

“Okay then, I’ll do it. David don’t stop, just slow down a little.”

Zeelie unclipped his headset, jumped up onto the roof of our moving Ratel so we could swap places, “just don’t be getting too comfortable in the crew commander’s chair,” I quipped.

Grabbing the gunner’s fly-wheels, I traversed the turret through 60 degrees to aim at a single large tree about 400 metres away, our ten o’clock position. We’d be firing live rounds of course, but the tree was the opposite direction to Charlie Squad who, from radio reports on squad net, were just beginning to attract small arms fire from enemy positions.

Focused on my task I continued the unorthodox gun-sight calibration, shooting two rounds, each time making adjustments to the gun-sight and cannon position as we moved relative to the stationary target, then I called, “Gunner, load HE. Driver stop. Fire!”

From a stable firing platform my third round took out the tree. Job done, I traversed the turret to twelve, jumped out of the gunner’s chair and ordered Corrie to drive, then reported our ready state to the Squad. “Three Zero, this is Three Two Alpha, we’re a few minutes out your position … ”

With guidance from Saunders in the command vehicle, we moved quickly through the forest toward the frontline, safe in the knowledge our boys had just cleared through the area minutes earlier.

Contact was getting pretty hot ahead of us, so it was with a mixture of fear and pride that I opened comm’s again, “Three Two Bravo, this is Three Two Alpha, I’m dropping into line adjacent your position … ”

The morning contact in dense bushy conditions made target acquisition incredibly difficult so we were mostly reduced to firing at muzzle flashes rather than visible targets.

Sometimes, opposition forces were so well dug in we’d be forced to withdraw however, on this occasion, elements of 21st had been on the move until they met a wall of Charlie Squad resistance and within half an hour they simply melted back into the deep forest behind them. I don’t recall spotting a single hard target during this clash.

Photo 36 31 Charlie ‘shooting in’ her gun-sight the proper way near Mavinga. (Martin Bremer)

FAPLA radio intercepts betrayed new-found respect for our 90mm fighting platform, a factor which might’ve swayed their decision to withdraw before contact built up a head of steam.

It seemed like we had FAPLA on the back foot, evidently unable to get past us. October had started terribly badly for them, and the clock was beginning to run down toward the impending ‘wet season’ rains.

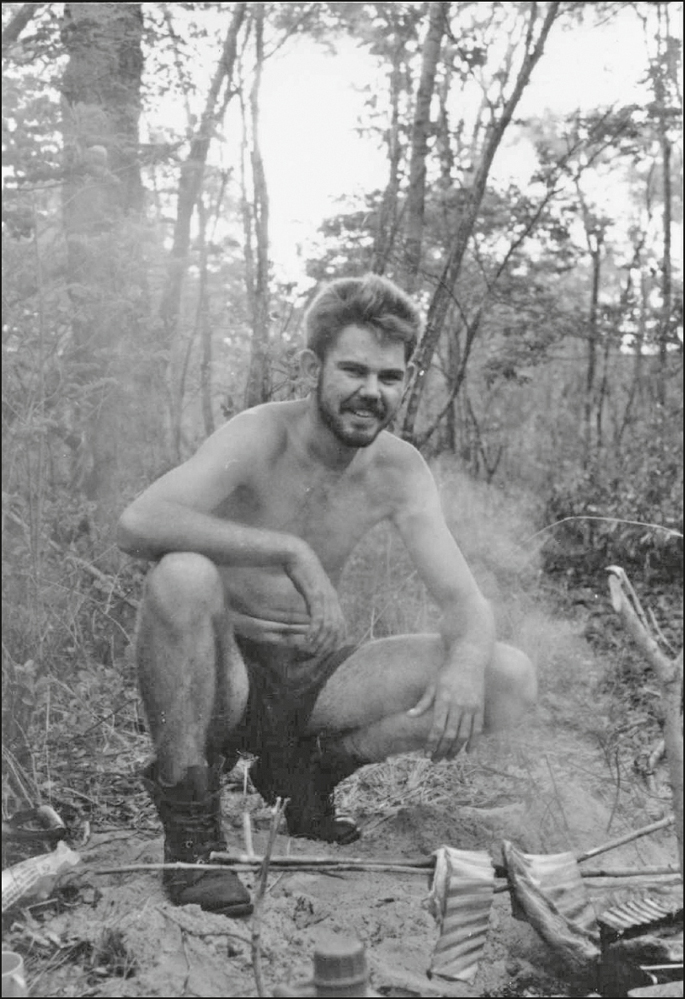

Photo 37 Pretorius celebrates with a rare feast of wet rations. (Len M. Robberts)

They appeared to be running out of options, which raised the appealing prospect that the worst of the fighting was behind us.

From a SADF perspective, it was a job well done that morning. We’d contained an expeditionary force of 21st Brigade, as BG’s Bravo and Charlie had done numerous times during September, continuing to starve them of the vital territory they needed to create a pocket for 59th Brigade to move in to on Lomba’s south bank.

At around this time rumours began spreading that enemy forces were possibly preparing to move en masse, pathfinders were believed to be scoping routes, heading away from us, due north!

It was far too soon to be certain, but perhaps the battering they took on October 3rd had been decisive after all.

With TG1 and 47th out of the equation, 59th was no longer on the offensive and 16th was seemingly going nowhere, they certainly weren’t moving south. The only other immediate threat was the battle-weakened 21st and by now almost non-existent TG2, these two units had gainfully defended the bridgehead for five long weeks despite relentless SADF Artillery bombardment and frequent ground-force clashes.

And then finally it was confirmed, the hardy warriors of 21st Brigade were being withdrawn from Lomba altogether.

We’d stitched the lining of our pocket with a thread of iron and steel so strong history would never again see it breached by military forces of Communism. The mood in the laager that night was jubilant, a few warm beers were shared, but any notion our war was coming to an end, or that all the hard yards had been run, was to be obliterated in the most dramatic fashion less than 36 hours later.

We were informed that and unplanned second phase of Operation Modular was to begin, a phase destined to destroy my naïve sense of invincibility and have a most profound impact on Charlie Squadron morale.