Try not to look at a temple sacred to Classical gods with the eyes of a Christian or Muslim, seeking similarities to churches or mosques. Its function was entirely different. The pagan devotee prayed, made offerings and offered praise outside the temple. Inside was the house of the god, inviolable and to be visited only by the priests, who were usually civic officials appointed for that purpose. (Some sacred places – particularly those where oracles could be consulted – did have permanent priests.) On special occasions the image of the god might be brought out from within the temple, in order for it be seen or to watch an offering; otherwise the god remained hidden – a work of human hands occupied by the power of what was imaged.

In Italy, Sicily the Lebanon, Syria and even in southern France, it is still possible to find temples with their internal structures more or less in place. In Asia Minor and Greece itself, little usually survives other than tumbled columns and the podium – the stepped platform on which the temple stood.

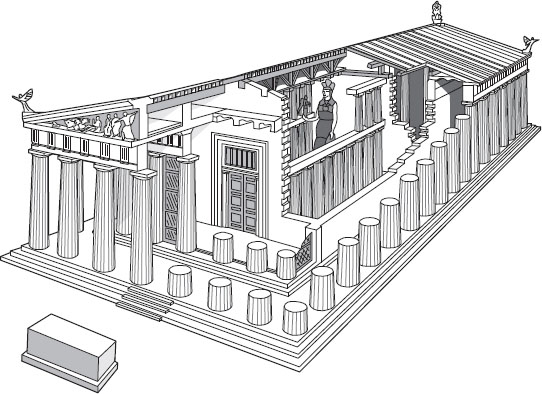

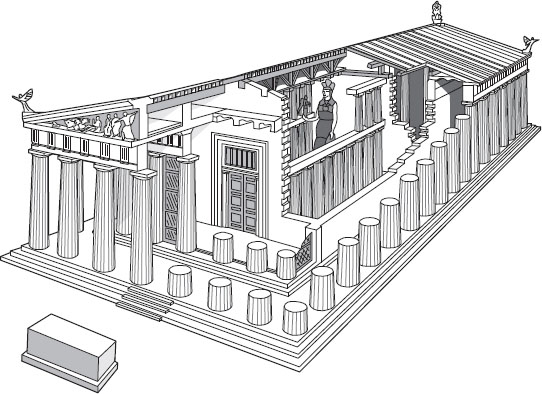

The temple’s general external appearance, with its surrounding rows of single or double-depth columns, will be familiar to everyone. It is what happened inside, and outside at the front, that needs explanation.

Before the temple, outside and free-standing, was the altar: the place where the sacrifice was made to the deity. In many cases this is now only visible, if at all, as a relatively small area of paving on the ground. It is the spot where, during the course of public festivals, the animals were ritually killed and some of the offal, bones and blood burnt so that the smoke could ascend to the god. The meat was then cooked and distributed to the participants as part of a feast. In the case of a large festival, these could be many, demanding a correspondingly large number of animals.

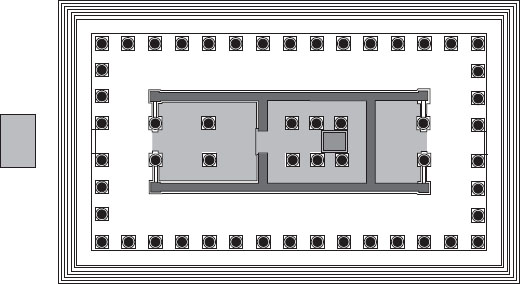

At the front of the temple was a massive door or pair of doors, set into the solid interior walls that were largely concealed by the external rows of columns. These doors completely secured the interior space. They led either directly or via an anteroom to the shrine – the place of the god and of his or her statue. Beyond this again, at the back of the temple, was a further room (or rooms), accessed via the shrine or, more commonly, by means of a smaller but very strong rear door. This was the strongroom or (in Latin) the cella: the place that performed almost the function of a safe deposit in a modern city. It was safe in two senses: an intruder would have to violate the place of the god to reach it, and it was the most strongly secured and hidden place in the temple. In it were placed the temple treasures, including the gold and valuables presented to it. The civic treasury and private deposits of valuables were also stored here.

A great deal is not known about the exact use of pagan temples. For example, it is uncertain to what extent the sanctuary was accessible, once the main doors were opened, to visits by worshippers in small groups; and it is a moot point whether the image of the god was regarded as a living thing (making its worship real idolatry). There is some evidence that it was, particularly by the ignorant; but there is rather more evidence that the nature and power of the deity were believed to somehow infuse the image. (The same ambiguity exists in the ‘worship’ of saints and relics in certain Christian traditions.) But it is certain that token offerings were regularly made to the images in the hope of favours or the granting of prayers. It is also certain that temples were used for the making of oaths, a special element in Greek legal commitments, and that a select few – Didyma, Claros, Delphi and Cumae, for example – were regularly consulted as oracles. Remember that there were no holy men. It was the places that were holy.

Cut-away reconstruction of a Classical temple.

Typical ground plan of a temple, showing its interior spaces: (from left to right) the anteroom, shrine and strongroom.

Although Classical antiquity was polytheistic, the number of Olympian gods was quite small: Zeus (‘father of gods and men’), Hera (his wife), Athena, Apollo, Artemis, Poseidon, Aphrodite, Hermes, Hephaestus and Ares (god of war – the Roman Mars), together with Demeter and Dionysus. In each city one particular god would receive special honours (Athena at Athens, and Artemis at Ephesus, for instance), but not to the exclusion of others. Coexisting with the Olympians were the gods of the earth and the underworld: Hades, Persephone, the nymphs (and numerous other minor deities of lakes, rivers, forests and mountains), Pan, and the household gods (gods of the hearth).

As the Hellenic world changed into the even larger multicultural and cosmopolitan Roman world, so the tendency to receive new deities into the pantheon of possible gods gathered pace. This trend came particularly from Egypt and the East, but also from the Roman habit of identifying the gods of conquered or protected territories with their own gods, who in turn were mostly the Hellenic gods called by different names. But the gods never excluded each other. In the 2nd century AD one visitor to Didyma, Apollo’s great sanctuary, observed how it was encircled by altars to every deity.

Was this plethora of invisible divine beings really believed in? With the sort of qualifications and details so admirably set out in Robin Lane Fox’s fine book Pagans and Christians (London, 1986), the best brief answer is still the one given by Edward Gibbon:

The various modes of worship, which prevailed in the Roman world, were all considered by the people as equally true; by the philosophers as equally false; and by the magistrates as equally useful.

* * *

The subjects I have touched upon in the above chapters can be followed in greater detail, together with many other items, in The Oxford History of the Classical World (Oxford, 1986): a book written by expert scholars but in a readable form.