‘Not with seven leagued boots but with elephants and camels like an Eastern damsel with all possible dignity.’

From the fair copy of Charly’s journal made by W. H. Ramsey in 1857

By the beginning of 1800, Henrietta’s passion to travel within the India of her imagination had evaded her. Unwell with one of India’s indigenous fevers, she remained confined to Madras which was now beset with January rains. Determined to experience her own India, she held steadfastly to her need to realise her simmering ‘indescribable wish’. By the end of January her prospects to travel began to look more promising.

January 22nd, Henrietta to Lady Clive

My dear Lady Clive – The night before last I gave a great ball for the Queen’s Birthday and your granddaughters danced from ten o’clock till near three in the morning and could have gone on a good while longer. I confess I was not easy about them last year, but now they seem quite stout and I hope a little change of air during the hot months will be of great service to us all and we think with some pleasure of going to more distance from this place and seeing a little more of the country.

It is impossible to imagine the sameness and dullness of this place [Madras] and the confinement in the morning is a very unpleasant circumstance to us. We had a few words in general of the good health of all the family from William Strachey by the last overland dispatch, which was a great happiness to us, yet we long for letters from everyone. In particular at this horrible distance every little circumstance is very interesting and it is many months since I had a word from you. I cannot help thinking of a good fire and the little worktable near it where I used to sit at Oakly Park, with nieces and children at another table, with great envy and had rather see one of the old oaks than the finest Banyan Tree in India.

The fleet carries home General Harris and his family all covered with money and jewels from Seringapatam. Mrs Harris is a very good woman with a great many children and has taken the greatest care of them here and will now I believe be much happier for all the honours that will probably attend the General such as Peerage Lord if that is to be the case in England. Most of the people I know the best are going at the same time which will not render this place more agreeable.

Charly’s diary gave some indications of the happenings at Madras for the next few days:

January 26th Flirty’s bad health caused us to send her home under the care of Mrs Kindersley. She appeared in the procession that attended General Harris on his departure; she was carried by one man and her basket by another.

January 27th The elephants taken at Seringapatam went off today, a present to the Nizam. One had a golden howdah and cloth worked in black spots, to imitate a leopard; the other a silver howdah, and cloth similarly decorated.

January 31st, Henrietta to George Herbert, 2nd Earl of Powis

My dearest brother … I am now at the Mount for change of air. Our last expedition was not so good. When I wrote last, rains came with violence and we were obliged to come way from William Call’s, which Lord Clive has taken for a few months … I hope we shall set out to Ryacottah and Bangalore in March.

Lord Clive will once again be denied the opportunity to travel as he is to remain in place to look after great works that are going on in the Government, no less I believe than the regulation of the Judicial and Civil establishment all over this country. Therefore there was a great doubt if Lord Clive could leave this place for a week without the Government being in charge of the council, which was not approved. The power being great and there are many obvious objections (which you will understand) to the power being in any hands not quite white which must have been the case. It seems that it might for a few days and that he may visit us and see a little of this country, which I am sure will be necessary for his health; when we are gone the house will be even less cheerful than it is now.

We expect great pleasure and health to attend us. At least it will be variety.

I am now under the disagreeable necessity of hunting for a maid amongst soldiers and sergeants’ wives. Two I brought are disposed of: Lee’s sister is married and a fine Lady and Thomas’s wife nursing a child. Sally is with me, but I fear in a bad state of health and has been scarcely well enough to attend me more than a few days at a time for some weeks. I am afraid she will not be able to be of much use on our journey. Therefore I have your nieces only to assist me.

I assure you, seeing General Harris and all those people setting out was a sad day. We gave a great breakfast to them and all the settlement. The streets were lined with troops and it was really a fine sight and one could not help wishing oneself in the same situation.

Lord Clive is well and is in good spirits. The girls I do now feel perfect. I long to hear from you and above all to see you. The fleet sailed the 26th January; therefore, you may know when to expect them. God bless you. My love to my dear Boys. How I long to see you all again.

Ever, my dearest brother,

a thousand loves to you, affectionately

H. A. C.

Henrietta undoubtedly was busy with preparations for the journey; there are no journal entries for February from her and only one from Charly: ‘February 3rd We went with Papa to the Garden House and breakfasted in the Octagon, a pavilion at the end of the grounds, that has always belonged to the Governor. The Nawab claims it, and as Papa does not choose to enter into any discussions with him, he relinquishes it.’

Finally in March everything was in place for the four female travellers to set off on their adventure. The journey itself got underway with great fanfare on March 4th, as indicated by Charly in her journal: ‘After having seen the Body Guard reviewed, we commenced our journey in palanquins, and took possession of our tents (which had previously been pitched) by the Race stand, seven miles from Madras, and about one and a half miles from St Thomas’s Mount.

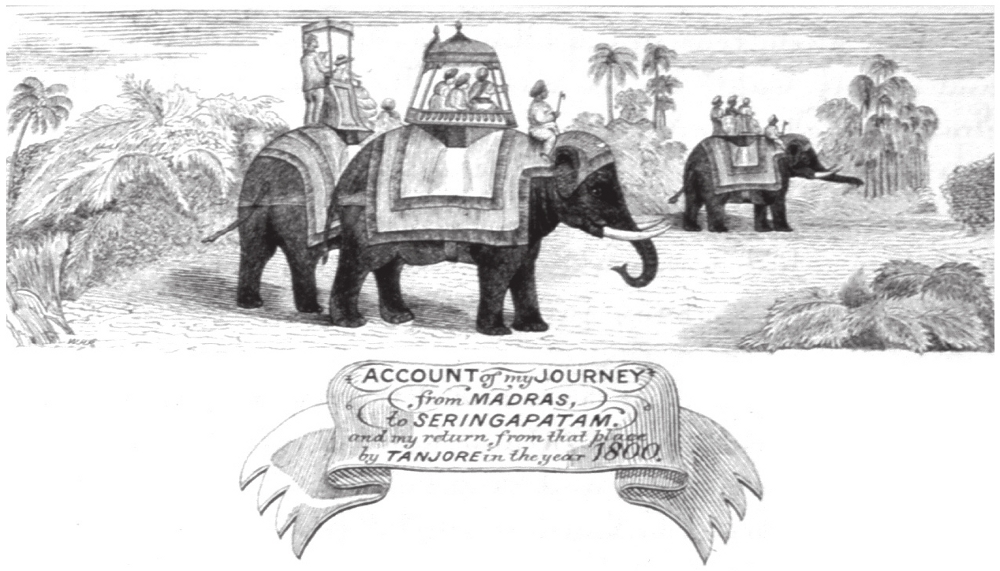

‘Fourteen elephants were employed to carry our tents, which consisted of two large round tents, six Field officers, three Captains and several smaller tents for the cavalry, infantry &c. by whom we were escorted. Four elephants were employed in carrying a part of our baggage; two were not loaded that had been trained for carrying howdahs, which we sometimes rode when the weather was not too oppressive. We had two camels, which were mostly used for carrying messages, and one hundred bullocks to draw the bandies in which all the rest of our baggage was to be conveyed.

‘Our party consisted of Mamma, Signora Tonelli, my sister and myself, Captain Brown, and Dr Horsman. Papa, Major Grant, Mr Thomas &c. only came a short way with us, as it was impossible for the former to be absent for any length of time from the seat of government, without resigning his situation till his return; which was very unfortunate for us, as by that means, we had not his company farther than Chingleput.

‘Mohammed Giaffer commanded the detachment of the bodyguard, consisting of 30 men; and the infantry were commanded by a Soubadar and a Jemadar and amounted to 66 men, including 16 boys, who had been selected to act as our orderlies.

‘We found it necessary to take all our servants, for travelling in India is not like travelling in Europe, as were obliged to take every article for cooking &c. &c. that could possibly be wanted. This of course occasioned a great number of followers, as all our servants took their wives, and those of higher caste their slaves to prepare their meals, which do not give great trouble, as they only eat boiled rice and curry, the latter of which is made up of meat and vegetables, which they never vary, and only drink water. When every soul was assembled they amounted to 750 persons!! … which is not in India a very great number, and it is not to be wondered at when all is considered.

‘We remained at this place the next day and saw Lord Wellesley’s bodyguard reviewed. They were then under Lieutenant Daniels command. I saw the great superiority the Madras bodyguard had over the Bengal; they had been trained under Major Grant’s orders and Lord Wellesley testified his approbation by increasing their number, and ordering a body of them to follow him to Calcutta, chosen out of this fine corps, and which were not ready to embark.’

On March 6th the four wayfarers were awakened ‘in a truly military style by the reveille being beat round the tents at four o’clock in the morning’. Not long after they recommenced their journey, breakfasting in Mr Smith’s Choultry at half-past seven at Vandalore. Charly elaborated: ‘The latter part of this journey had been through a jungle, and after being accustomed to the flat situation we had but just left; we were well pleased with the hills, though those, which we passed on our road, were not very remarkable. It was not till the middle of the day that we reached our encampment at Calumbankam about two miles from Vandalore Choultry. We had been detained by one of the largest elephants becoming very riotous, and by passing his trunk under the legs of two other elephants he had thrown them down, which occasioned great delay, as it was some time before they could be properly loaded again.’

The heat was intense; in the tents, the thermometer was at 94. Somewhat ruefully Charly commented: ‘We were not for the first few days in good train, and did not proceed regularly till we got a little more accustomed to this method of travelling.’

Charly described in some detail their tents: ‘Mamma had a Field Officer’s tent, Signora Tonelli had another, and my sister and myself had one placed between them. Sally Rubbathan and Charlotte Fisher were in a Captain’s tent close to us, Marianne had a private’s. This was enclosed by what in India is called a Knaut, and which the native princes when they travel in India have always around their wives encampment. It was a kind of tent wall that went all round us and sentinels were placed at the entrances.’

Their first day’s journey was 16 miles. Afterwards, in the cool of the evening they walked to a tank surrounded by banyan trees. ‘We thought them beautiful,’ Charly wrote ‘and had not seen anything which reminded us so much of English oaks.’

March 7th, Henrietta’s journal

Set out at half-past four and arrived at Chingleput at half-past seven. The first part of the road was rough but the approach for the last five or six miles was beautiful. I drove the bandy for the first time without any difficulty and was much pleased with the appearance of the country. The distant hills – broken, rough, and strong – were very much like those at the Cape and near the Mount. There was a pretty tank on the right about five miles from Chingleput. As Lord Clive and myself had gone on faster than the rest of the family that followed in their palanquins we got out of the bandy at a Mussulman burying place and remained under some tamarind trees till they came up. Captain Wilks told me that the way one distinguished between the tomb of a moor man and woman is that the first is always raised and the second hollow at the top. The Sultan brought a pomegranate and some mint, the only productions of his garden. Soon after, the Amildan arrived with tom toms on each side of a bullock (something like little drums) with dancing girls and wreaths of flowers which he put on our shoulders and gave limes to Lord Clive. We proceeded attended by all these people to the town at the end of which William Hadee, Collector, met us.

The lake is beautiful surrounded with hills putting me much in mind of Switzerland in miniature. I went to the Commandant’s house and thence to the Raj Mahat, the remains of part of an ancient palace of the Rajah of Chingleput. This building is in a very strange shape and has a room surrounded by a sort of veranda. The staircase, if it is to be called so, is so narrow as scarcely to allow a person to go up and the steps just wide enough to allow a foot each turned out to tread on them and in total darkness. The view from the top of this building is very extensive and fine. Though the lake now appears so fine, last year there was not any water in it at all. They hunted boars upon its bottom. The fort has been partly repaired and partly is in a decayed state. At the entrance of the fort there is a choultry and beyond it a pagoda and under which is the gateway through which you pass before you come to the drawbridge. The commanding officer’s house is very pleasantly situated over the lake and there is good room in it.

About 12 o’clock I went to the encampment at Attour, two miles W of Chingalput. Owing to some great mismanagement of the elephants our baggage did not come up till after eleven and it was one o’clock before my tent was pitched. A great many tumblers and rope dancers came and performed very well before the tent, particularly two or three very pretty things. One man was carrying a girl on his shoulders and she carrying a large earthen vessel supporting it with one hand and the other extended. It was a good exhibition for that sort of thing. The Commanding Officer dined with us in camp and Lord Clive set out to Carangooly in the evening with William Hudson.

March 8th We set out very early in the morning to Carangooly. The road grew wild and uncultivated, except near the village. We passed a pretty pagoda upon a high hill. About two miles from William Hudson’s, we were met by dancing girls with tom toms, who attended us to his house. The lake is of great extent and surrounded by distant hills. There is a view of the ruins of the old fort. The view was very striking as we approached the village built by William Place. It is uncommonly neat and enclosed within gates. Each house has a veranda and nut trees planted before them. The inhabitants are the different people employed by the Collector. Trees line the small streets on the right hand, cropping the road. There is a bungalow built by William Hudson. New seeds that we had given him perished there, not having been sufficient water for more than the common uses.

I felt here the comfort of a house in comparison with a tent. The heat was not disagreeable. The hills rise immediately behind the house. In one of them a few months ago while Mrs Cochbasse was sitting in the veranda, a tyger was seen walking quietly across. She was the first person that perceived it. He made his escape to another hill and it was two hours before he was shot. He retired into an aerie in a rock and it was a considerable time before he was killed though there were many people with a variety of arms. William Place’s house was bought, by the East Indian Company, for the use of the Collector. On one side is the collection, where all the clerks write and all causes are tried, as well as the papers and commanding a much finer view than the house built by William Place. It was begun years ago, as well, as the garden. The trees grow well.

After dinner I went with Lord Clive in a bandy to the old fort. It was attacked and destroyed by Col Moorhouse in the year 1780. The gateways are completely destroyed. There are small remains of the Killadar’s house and a building where Haider shut up the inhabitants before he carried them away. William Hudson had begun a plantation of tobacco and other trees but the nursery is to be made near Vellore – this one not being thought sufficient, and that one nursery of a considerable size, is better than many small ones.

The village of Carangooly is neat, but not so much so as the first village. There was a fine tobacco centre and several paddy fields in great vigour. We returned by the works made to dam up the bed of the river and to form the tank. The sluices were opened that I might see the rapidity of the cascade so that though there was so much water last year it was dry during the monsoon. William Hudson gave me some specimens of a black hard stone used for building. It had much the appearance of basalt. He called it granite. The air was particularly fresh and delightful and very different from that of Madras. The country is perfectly healthy.

On March 9th, Lord Clive left in the evening after they had dined and returned to Madras, travelling all night that he might arrive at Madras to breakfast the next morning. The travellers would not see him again until October. Perhaps because of the parting, Henrietta’s journal had more complaints than were usual for her: ‘The sun was in our faces. The palanquin boys did not carry me well and I was most completely tired. The heat was intense in my tent all day.’

In order to avoid the heat the march usually began before daybreak with a boy carrying a lantern by the side of each palanquin. Henrietta drove her own bandy when possible, and at every opportunity she collected botanical and geological specimens.

Charly’s March 10th journal entry described their early morning departures: ‘As we were by this time more accustomed to our travelling, we went on in a very regular manner after this period. The general was beat round the encampment, and in an hour afterwards, we were in our palanquins; the ground was cleared, and the baggage all followed in about an hour after. Two Dragoon rode first, then a Chobdar on foot, with his silver stick; who was followed by a Hircarah and two peons. Mama’s palanquin led the way, next came my sister’s, then mine, Signora Anna’s, Captain Brown’s, Dr Hausman’s, and our female attendants; Jemadar Giaffer with two Troopers, followed the whole. When the weather was fine, Mama drove one of us in the bandy, and the rest of the party mounted elephants for variety.’

Frequently, Henrietta, Anna, Harry and Charly stopped to visit pagodas and to learn about their gods. One of these occasions Charly described, ‘as the most extraordinary things I ever saw … the priests covered us with flowers which I am afraid we did not receive with proper respect, for we were much tempted to laugh at the solemnity, with which they treated these frightful stone and wooden figures. We were also entertained by dancing girls … We returned from these curiosities through a magnificent choultry, supported by one thousand pillars. We were told it was built in imitation of the one in Madura …’

Although they continued to enter the Hindu temples whenever they were allowed to do so, more and more the travellers seemed to express a preference for Muslim edifices, finding them less overwhelming. In the evening they continued their journey and ‘were shown the principal Moorish Mosque, which is pretty from its neatness’. Charly reflected that ‘perhaps it appeared pleasing to us from the contrast we drew from what we had seen in the morning of a different style of architecture. There are but few Mussulmen in this town, and the Mosque is not therefore of any particular beauty.’

March 11th, Henrietta’s journal

The country is beautiful and put me very much in mind of Maidenhead. At little Conjeveram I was met by all the tom toms on foot and upon a bullock with polygar spears and an elephant, that salaamed most politely as I passed. The multitude of people was quite amusing, but the noise and the dust were very great. Upon a very white pretty pagoda there were many monkeys very ugly with reddish furs. They came and chattered upon the wall as we passed. I went to the Collector’s house to breakfast. It is very pleasantly situated in a garden. The upper story was large enough to contain us and we remained there all day. The streets are much better – wider, and cleaner than any town I have seen in India. There are trees planted before the houses, which are decently built, and the inhabitants are clean and have the appearance of comfort.

I went to the Great Pagoda. It covers a great deal of ground with all its choultrys and houses and a tank that is very large. I could not discover when the pagoda was built or by whom. They seem to have no tradition of it or of any of their buildings. The steps are steep and the staircase totally dark. I went up the two first stories with great surprise. The ladder was more than I could handle. I went up a few steps, but my head grew so giddy I was obliged to return. Signora Anna, the girls and everybody else went to the top. The view is very extensive. We saw a good country with a great deal in cultivation. The hills at a distance are wild and fine and I was much pleased with the whole scene. From the top there is a more commanding view, but I saw as much as satisfied me.

In the evening I went to the pagoda at Little Conjeveram with all the tom toms with us. Mr Hodgrove had ordered them. The priest came out with flowers and limes. This morning the priest had not prepared this as usual. I heard that Mr H’s peons scolded them and they (as we suspected) brought some that were a little dead from their god. At the entrance of one of the great Swami’s houses there are two colossal figures of granite with four arms, each which are supposed to be the guards for the temple. Mr Place gave a large gilt pillar to hold blue lights, which is placed before the temple. There were many monkeys: some came down to be fed; one had a young one carried upon its heart. They were very ugly. After coming from the pagoda in the morning I went into a small neat mosque built over the tomb of a holy man, his mother and servant who had been dead one hundred years. There was a little table before the tomb with some perfumed sticks burning and some flowers. It was neat and pretty and much superior I think to the Hindoo Gods and monsters.

March 11th, Henrietta’s journal

We proceeded as far as Avaloor Choultry, and entered upon the Nawab’s dominions which we found in a very different state as to the appearance of the country, which is thinly inhabited, and but poorly cultivated, and in most parts appears barren and miserable. The difference from the Company’s territory, which we had just left, was very great, and evidently proves, which is the best managed.

Charly added a few details in her account: ‘The Nawab’s Dewan came from Arcot here to meet us, and prepared a pandal for our reception. He did not come in very great state, but his dress was very magnificent, as well as that of his son, who accompanied him, and who appeared to be about 12 years of age. The Dewan … made us a present of a dinner (an act of civility). He encamped near us, and paid us another visit in the evening and was uncommonly civil.’