|CHAPTER ONE|

Who Are We? Why Are We?

THE GREAT CANADIAN literary theorist Northrop Frye said that while most countries’ literature asks the question “Who am I?,” Canadian literature asks the question “Where am I?” Canada is an anomaly of both geography and history. Canada is neither America, nor Great Britain, nor France. There was never a mandate for Canada to exist; it has existed by default. Canada is a country born without a mission statement.

This lack of mission statement has created a crisis of identity, which has created a crisis of confidence. The most salient question is not “Where am I?” or “Who am I?” but “Why am I?” And I think “Why am I?” is at the heart of Canada’s inner torment. Because we don’t know why we came to be, we have a low self-image that puts us in a constant state of apology. We are in a sorry (“sore-y”) state. Don’t get me wrong, I love that Canada is polite, but we’ve taken apology to a burlesque level.

If a Mexican standoff is two people locked in an armed conflict for which there is seemingly no peaceful resolution, a Canadian standoff is when two Canadians come to a doorway, each of them beckoning the other to go first. Two Canadians will stand there for hours, because they’ll say to themselves, “Who am I to go first?” When civility is taken too far, as it often is in the case of Canada, the entire country ends up stuck on the threshold, both literally and figuratively. We need to cross that threshold. Until we do, we won’t have realized our full potential.

Culturally, the totem and taboo of Canada are not as clear as those of ancient, stifling, folkloric Europe. How straightforward and evident it is to be European. Could we expect Canada to compete with European cultures that have existed for centuries? Their history is literally carved into their cities. Toronto will often claim it’s a world-class city. Paris simply claims it is Paris.

Let me illustrate. In Canada, if somebody came up and punched you, a Canadian would ask, “What did I do?” In America, if somebody randomly punched you, most Americans would ask, “What’s that guy’s problem?” America has more of a sense of itself than we do. They have a clear mission statement, we don’t.

Americans individuated from stuffy old Europe by becoming the best storytellers in the world. They wrote their own powerful creation myth; they wrote their own powerful mission statement. It’s been said that Rome ruled the world with the broadsword and the phalanx, and Britain ruled the world with the three-masted ship. America, it seems, is ruling the world with the moving image. Hollywood industrialized mythology, and then weaponized it. It is widely believed that the Soviet Union folded because they couldn’t compete with America’s missile shield program, nicknamed Star Wars. I’d argue that the Soviets folded because they couldn’t compete with the movie Star Wars. The Soviets must have seen the sheer mastery of American storytelling through Star Wars and thought, Holy jumpin’, they even have enough story power left over to create an entire immaculate universe? The story of dialectical materialism doesn’t stand a chance.

This is my copy of the first issue, from 1975. Americans don’t believe that there’s a Captain Canuck, and they’re even more surprised when I tell them Canadians invented Superman.

This is a birthday card my mum sent me. However, I think the artist may have taken a picture of me by Lake Ontario when I was a kid. I had that jacket. And notice—see this page—that the Adidas has four stripes.

Americans have such a surplus of narrative that they’ve even created some of Canada’s legend and lore. Take the Royal Canadian Mounted Police: it’s known around the world that the Mounties “always get their man.” In reality, the RCMP has a capture rate in line with most federal police forces. But this idea that “the Mounties always get their man” was created out of whole cloth in Hollywood.

It should be noted that too much mythmaking has a downside. For example, America is number 1 in confidence, but number 29 in education (Canada is number 10).

When Canada tries to create its own legend and lore, it falls short. For example, the city of Toronto had a contest to name the city’s garbage cans. Torontonians sent in names like Gary Garbage, Tommy Trash, and Billy Bin.

Alas, the genius that is Ricky Receptacle.

The winner was Ricky Receptacle. I’ll say it again: Ricky Receptacle.

While it’s true that Canada lacks a mission statement, and this has been a source of national anxiety, I maintain that we actually know ourselves better than we think.

What we do know is that we’re a country with the two solitudes of English Canada and French Canada. We do know that we are not so much a melting pot as we are a salad bowl. Up until recently, we had a Ministry of Multiculturalism. While we don’t have a uniquely Canadian instrument, like America, which gave the world the banjo, the Ministry of Multiculturalism fostered respect for the indigenous instruments of each immigrant’s home country. Canadians are also aware of the fact that we don’t have a famous cuisine. In New York City, I’ll go out for Italian, Chinese, or Mexican, but when’s the last time you went out for Canadian? You didn’t. And don’t say poutine. That’s a topping.

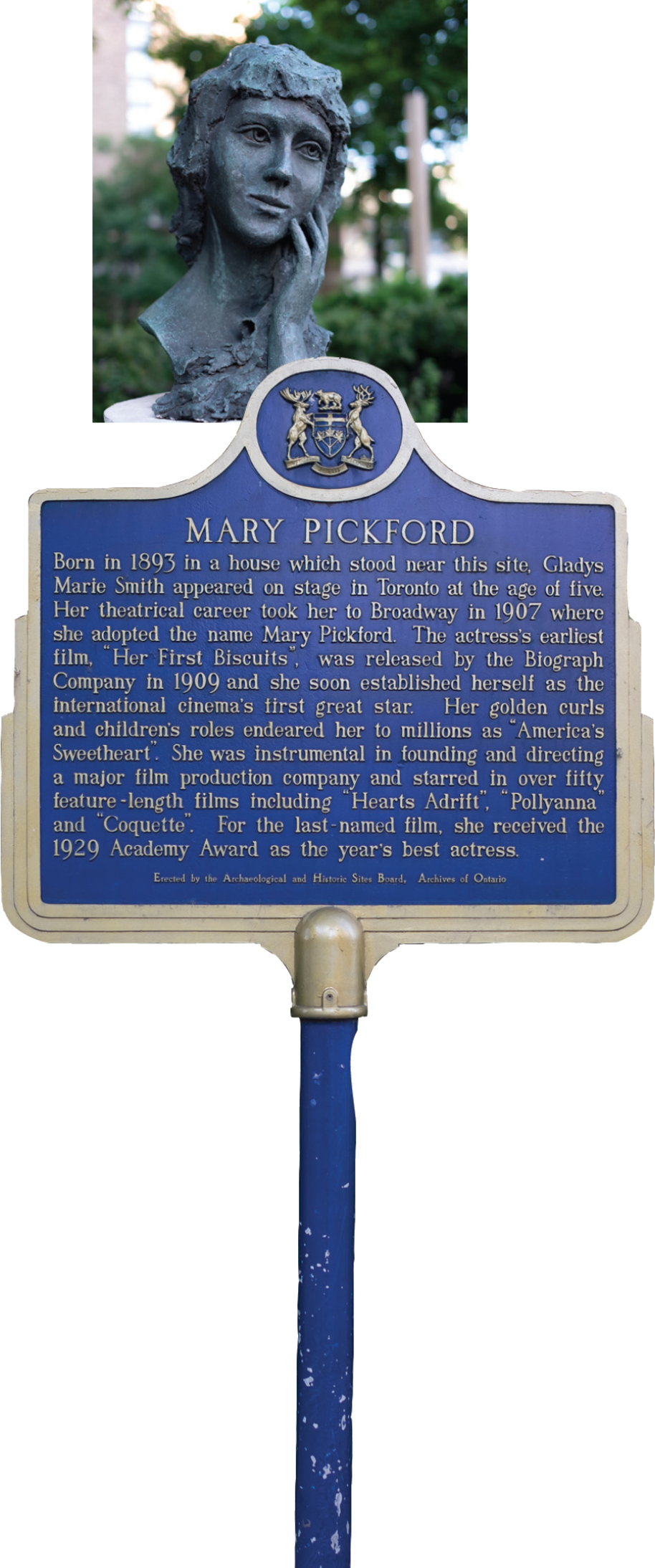

We know we don’t have a “famous” cuisine, but we also know we do have “famous” ingredients. B.C. apples, Saskatchewan wheat, Nova Scotia salmon, and Manitoba…stuff. Ingredients are what help define Canada. Likewise, Canadian culture as a whole may not be famous, but the “ingredients” of our culture are. For example, we didn’t invent folk music, but Saskatchewan’s own Joni Mitchell perfected it. We didn’t invent rock and roll, but Ontario’s own Neil Young redefined it, adding the “high lonesome” wail of the Canadian heartscape. America’s Sweetheart, Mary Pickford, was born in Toronto. Canadian Mort Sahl, a contemporary of Lenny Bruce, is considered the father of American political satire. Andrew H. Malcolm said, “Canada was poised to have French culture, American efficiency, and British government. Instead, they got American culture, British efficiency, and French government.”

In Canada in the 1960s, there was a contest to finish the following sentence: “As Canadian as…[blank].” Third place went to “As Canadian as hockey.” Second place: “As Canadian as good government.” Ultimately, the winner was, “As Canadian as possible under the circumstances.” What are those circumstances? Well, one circumstance is our climate. In Canada, for eighteen days out of the year, if you don’t have an artificial heat source, you’ll die within forty-eight hours. Margaret Atwood and Northrop Frye said that this created, for Canadians, a “garrison mentality,” whereby the central conflict of much of our literature is man versus nature. That sort of conflict breeds cooperation more than it breeds rugged individualism. It breeds caution more than it breeds entrepreneurialism. It’s cold here. It’s so cold it can make you cry. It’s so cold you want your dad to come pick you up. Even when you’re fifty-three years old.

In fact, winter is so part of the Canadian experience that there is a French Canadian folk song called “Mon Pays.” It goes, “Mon pays, ce n’est pas un pays, c’est l’hiver,” or “My country is not a country, it’s the winter.” And in typical Canadian fashion, I only found out about this song when Patsy Gallant, a Canadian singer, co-opted the tune of “Mon Pays” but rewrote the lyrics to be about America, renaming “Mon Pays” to “From New York to L.A.” It was a smash hit in the States. What little bit of Canadian culture we had was rewritten into American culture—as a disco song, no less.

We’ve spoken of geography and climate as elements that define us. Canadian history defines us as well, but tragically, it is boring. In fact, I have offered Canadian history lessons to my American insomniac friends. By the time I tell them about the Beaver Wars, my American friends are fast asleep. Canadian history could be a drug-free alternative to anaesthesia.

BY THE TIME I TELL THEM ABOUT THE BEAVER WARS, MY AMERICAN FRIENDS ARE FAST ASLEEP. CANADIAN HISTORY COULD BE A DRUG-FREE ALTERNATIVE TO ANAESTHESIA.

The problem with Canadian history mirrors the problem with the Canadian identity as a whole. Our history is a series of often-unconnected facts and events, not driven by a mission. There’s no stated goal. In most movies, you know what the character wants by the end of Act One. Will he get the girl? Will he steal the gold? For the United States, the stated goal is, “Will the American Revolution survive?” We got nothing. Canada has had very few wars, and of those wars, none of them were protracted or bloody. Most national advancements came by way of legislation. We didn’t have a gunfight at the O.K. Corral. America sent settlers west, who then formed police forces. Canada sent out the Mounties first, and then the settlers. Let’s look at Canadian history…briefly.

In the 1500s, the French claimed the land the Iroquois called “Kanata” in the name of France.

In the 1600s, England established colonies in Newfoundland.

By the 1700s, Britain had defeated France in Canada (one conflict was called the Beaver Wars).

In 1776, America had a Revolution. Canada, however, remained loyal to the King.

In the War of 1812, Canada repelled an American invasion, ensuring Canadian independence from America. If you read a Canadian textbook, Canada won the War of 1812. If you read an American textbook, America won.

Ah, the beaver. Our national animal, representing Canada’s great outdoors, Canada’s industriousness, and Canada’s love of infantile jokes.

In 1867, Canada got its independence, not through an armed revolution, but through an unarmed evolution—a piece of British legislation called the British North America Act. Canada was the first country in the history of nation states to break peacefully from its mother country. More than anything, this shapes who we are.

Canada remained a Dominion of Britain, and would not get its own foreign policy until 1931, its own army until 1940, its own supreme court until 1949, and its own flag until 1965. Canada finally got its own constitution in 1982. That’s how evolution rolls.

Major-General Sir Isaac Brock. This British General repelled the American invasion at the Battle of Queenston Heights during the War of 1812. Even though he is English, he is one of my Canadian heroes. I did a project on him in Grade 6.

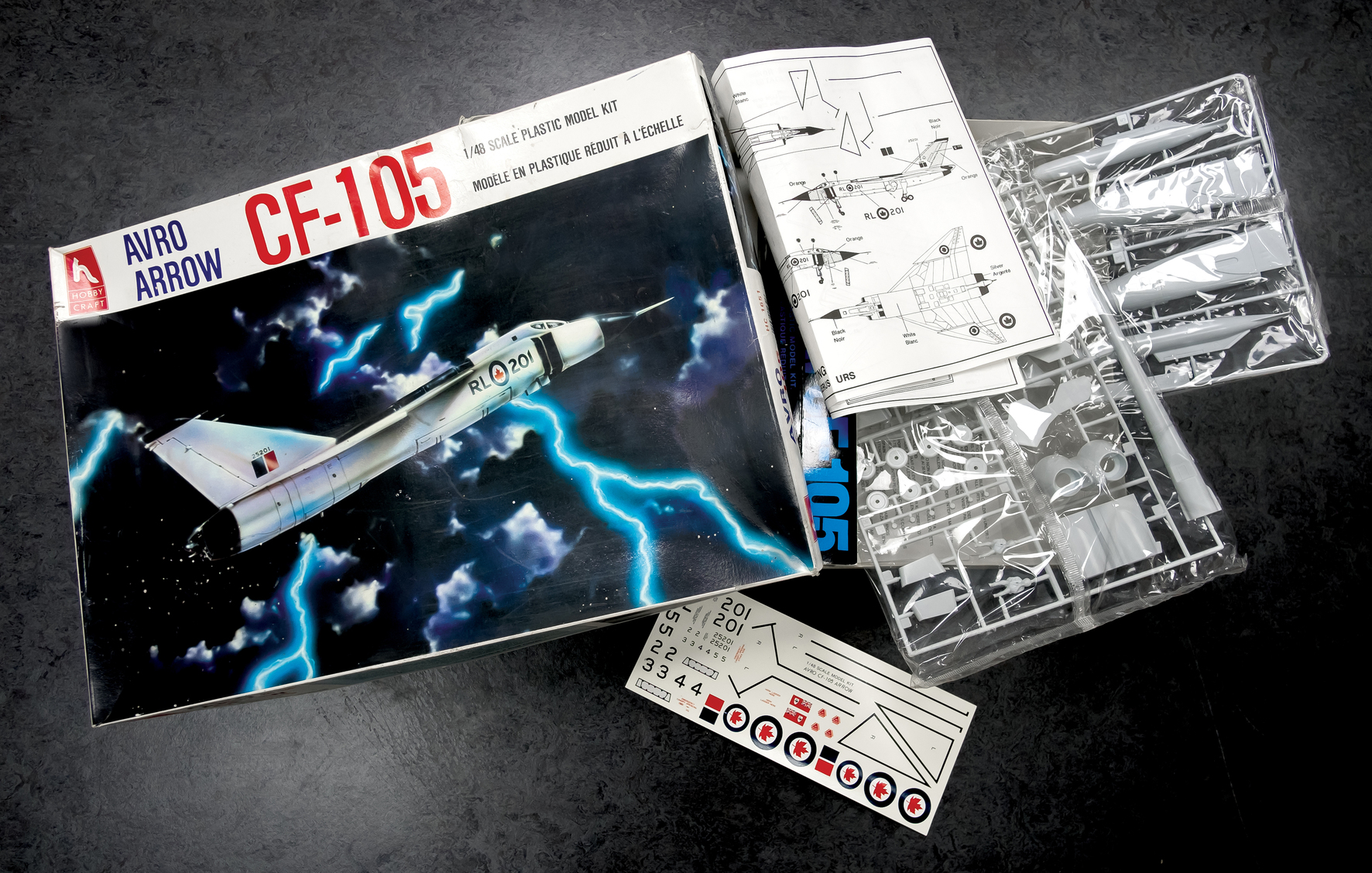

There is one bit of Canadian history that has always upset me. After World War II, Canada began to develop its own aviation industry. Its crowning achievement was the Avro CF-105 Arrow. The most advanced fighter jet in the world, designed by Canadians in Canada. In 1959, Conservative prime minister John Diefenbaker scrapped the Arrow in favour of the Bomarc missile system. He did this under pressure from the Americans, who, I’m sure, were not happy that Canada had stolen its lunch by designing such a cutting-edge piece of military hardware. It breaks my heart to think that we didn’t realize our full potential. We didn’t believe in ourselves, because we didn’t have anything to believe in.

We do, however, believe in statistics.

Canadians are obsessed with statistics. Well, seven out of ten Canadians are obsessed with statistics. And of those seven, 25 percent of them…you get my point. Canadians love statistics so much that there is literally a branch of the government called Statistics Canada. Other cultures contemplate their own navel through literature and cinema. We keep lists. Ironically, one of the best books that lists Canadian achievements was written by an American, Ralph Nader. Included in Mr. Nader’s list of Canadian achievements are items such as:

We invented time zones, the telephone, the first steamship, the zipper, the hydrofoil boat, the first short takeoff and landing plane, the first commercial jet transport, Pablum, the first credit union, socialized medicine, green ink, insulin, radiation therapy for cancer, the McIntosh apple, various strains of rust-resistant wheat, dry ginger ale, the chocolate bar, Greenpeace, IMAX film, the panoramic camera, the paint roller, the green garbage bag, lacrosse, basketball (we did!), synchronized swimming, the Blue Berets, Superman, the snowblower, the snowmobile, frozen food, ice hockey, virtually anything to do with the cold, and, of course, Trivial Pursuit.

We had the first publicly owned electric utility, the first plant to run on hydroelectricity, the first transatlantic cable, the first long-distance phone call, the first transatlantic wireless message, the first wireless voice message, the first radio voice broadcast, the first domestic geostationary satellite, the first steam foghorn, the first commercial motion picture, the first documentary, and the first motion picture showing in North America.

Canada’s obsession with lists is not only a compensatory mechanism in the absence of identity, but it’s also an effort to self-soothe. If you’re French, you don’t turn to someone and say, “Hi, I’m from France, home of Napoleon. We make wine, high-end cheese, and produce great artists like Chagall, Renoir, and Matisse.” No, in fact, French people say, “Hi, I’m French.” But, because nobody knows anything about Canada, we feel we have to produce a resumé after we say we’re Canadian. It makes us feel good about ourselves.

Canada’s own Wayne and Shuster. A staple of The Ed Sullivan Show. They planted the flag. So funny.

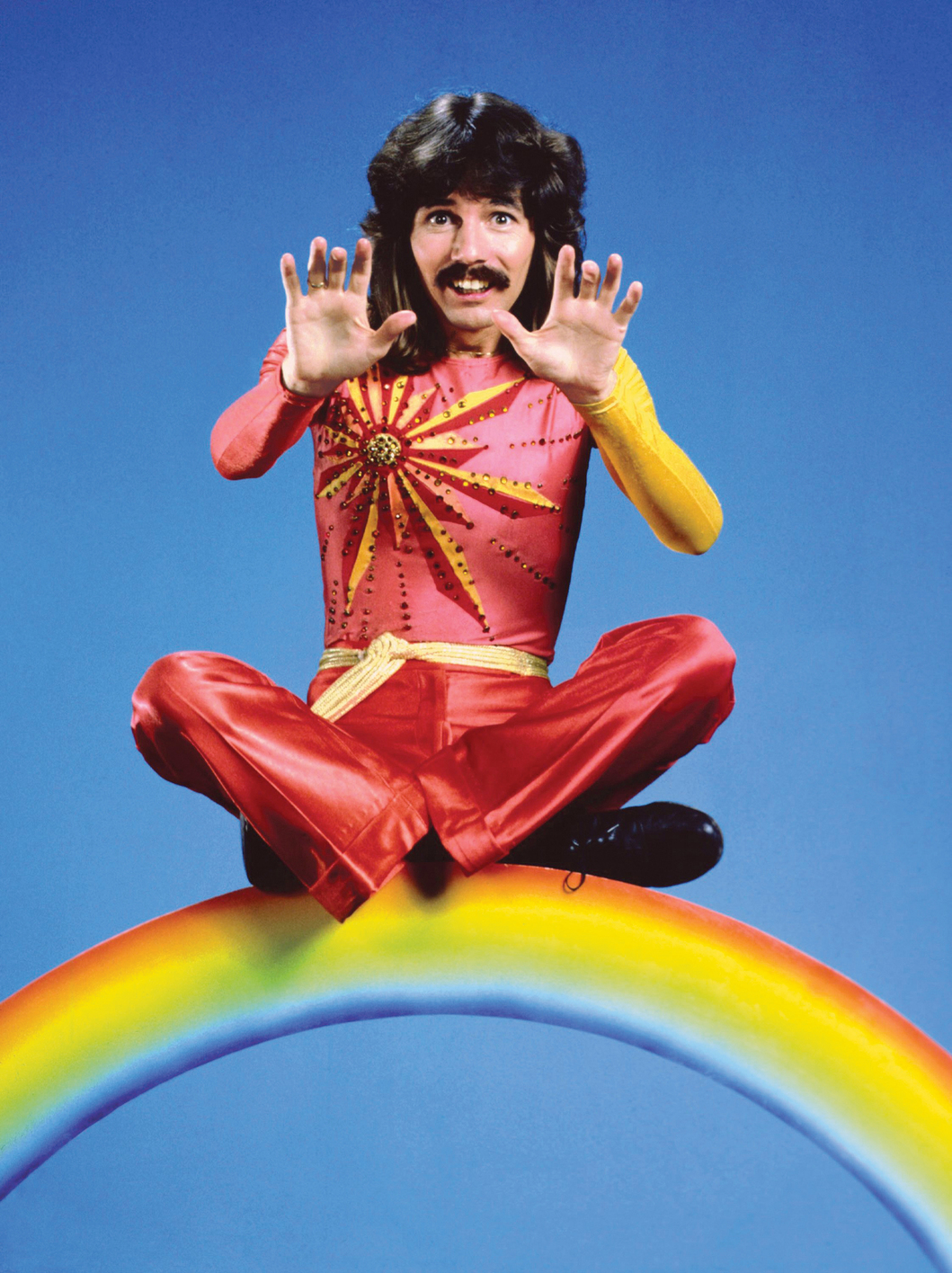

Doug Henning, rock and roll illusionist. Martin Short’s impression of him on SCTV is transcendent.

From the Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band cover. Note the Ontario Provincial Police patch. I can spot Canadiana in the parts per billion.

Canadians love it when other countries mention Canada. I still get excited when I hear Carly Simon’s 1972 song “You’re So Vain,” when she says, “Then you flew your Learjet up to Nova Scotia to see the total eclipse of the sun.” My brothers and I would cheer when she mentioned Nova Scotia. I guess we thought this song was about us, didn’t we, didn’t we? But years before that, I remember being so proud when I saw Wayne and Shuster being introduced on The Ed Sullivan Show as “Canada’s own Wayne and Shuster.” Holy crap, Ed Sullivan just said “Canada.” When Canadian Doug Henning, the long-haired illusionist who introduced rock music and rock costumes to the world of magic, mentioned that he was Canadian, we were thrilled. I also remember spotting an Ontario Provincial Police patch sewn on Paul McCartney’s costume on the cover of Sgt. Pepper. Of course, at the time there was a rumour that Paul had died, and due to the fold on his jacket, the OPP patch appeared to read OPD, which, the conspiracy theorists argued, stood for “Officially Pronounced Dead.” We knew it was the OPP. I can spot Canadiana in the parts per billion.

Then, too, of course, it was always great when Canadian artists who were popular in America would mention Canada. I get a little lump in my throat when Canada’s Neil Young sings, in “Helpless,” “There is a town in north Ontario.” And when Joni sings in “A Case of You,” “I drew a map of Canada, O Canada,” I weep uncontrollably.

This sort of sentimentality is one of Canada’s lesser-known traits. In fact, Canadians tend to be a bit…morbid. There, I said it: Canada is morbid. This morbidity is so subtle and so ingrained that I don’t even think Canadians realize it. I didn’t realize it myself until many years after I had left the country.

She is a Canadian genius. I hail you, Margaret Atwood.

“If the central European experience is sex and the central mystery ‘what goes on in the bedroom,’ and the central American experience is killing and the central mystery is ‘what goes on in the forest’ (or in the slum streets), surely the central Canadian experience is death and the central mystery is ‘what goes on in the coffin’.”

MARGARET ATWOOD, Survival.

When Canadians tell you a story, they always insert morbid, often superfluous, details. For example:

MIKE: How’s work?

CANADIAN: I got a promotion!

MIKE: Oh, that’s great. Congratulations!

CANADIAN: Oh, thanks.

[Pause, weird change of tone]

You know my friend at work, Bill?

MIKE: Yeah?

CANADIAN: (Gravely)

He had a heart attack, eh?

MIKE: Oh, I’m so sorry. At work?

CANADIAN: (Gravely, almost melodramatic)

No, at home.

[dramatic pause]

In front of his kids, eh?

“In front of his kids, eh?” I can’t tell you how many times Canadian stories end with “in front of his kids, eh?” It’s as if Canadians don’t have confidence that the information they’re imparting to you is going to be interesting enough—that it needs a tragic element fused onto it, to get your attention. But this kind of morbid storytelling isn’t confined to just local and personal events. Whenever a celebrity dies, I get texts.

And almost always, these texts are coming from a 416 area code (Toronto).

But this morbidity is drilled into us at an early age. At school every September, there would be an assembly welcoming the students back. Invariably, the assembly would include a list of teachers who had died over the summer. A disproportionate number of these teachers died either in horrific boating accidents or tragic hayrides somewhere “up north.” Each of their deaths was described in uncomfortably graphic detail. It was almost like a police report, and I’m fairly certain I was too young to be hearing about this level of carnage.

In Canada, November 11 is Remembrance Day. Every year in school there was a minute of silence honouring “Our glorious dead.” People wore poppies on their lapels in reference to the poem “In Flanders Fields” by the Canadian poet John McCrae. The poem was read over the PA system.

That poem scared the shit out of me. And I guess it probably should have.

The purpose of Remembrance Day is to honour our veterans, but it’s really about death. In America, they’ve parsed out one day for veterans and one for those who have made the ultimate sacrifice (Memorial Day). In Canada, we’re sort of all about the dead part.

November 11 is also my brother Paul’s birthday. Consequently, Paul is particularly prone to Canadian morbidity. Any time we drove past traffic accidents, Paul had the unnatural fear, even at the age of seven, that our car would be commandeered and turned into a “makeshift ambulance.” He specifically feared that he would be saddled with a “headless corpse.” I am not making this up.

One time, there was a plane crash at the Toronto airport. From our apartment balcony we could see a plume of smoke in the distance. We saw from the news that bodies from that crash were being stored in a hockey rink across from the crash site. We found that particularly frightening. At that moment, there was a knock at our door. Paul screamed, “Don’t answer it! It could be somebody asking us to turn our apartment into a makeshift morgue.”

Toronto is blessed with one of the greatest children’s hospitals in the world. Despite the fact that they perform miracles every day, this hospital has a remarkably morbid name: The Hospital for Sick Children. My American friends don’t even believe me when I tell them it’s called the Hospital for Sick Children—I always have to go online to prove it to them. They’re horrified. They say to me, “Isn’t it obvious that if the children are in the hospital, they’re sick? Can’t they change the name?”

And I say, “They have changed the name. They’ve shortened it. It’s now called SickKids.” Once again, I have to go online to prove it to them.

There is another fantastic yet morbidly named Canadian organization that gathers money for Canadian soldiers who have lost limbs. It’s called the War Amps. American friends ask, “What’s an ‘amp’?” I explain that it’s a short form for amputee, to which they recoil and say, “So, you guys shortened the word amputee down to amp?”

“Yes,” I say.

“Couldn’t it be called something like the Canadian Wounded War Veterans Association? Did they need to have the word amputee in the name?” they ask.

And I politely respond, “Yes, they did.”

Even Canadian sports can be morbid. American football teams win the Super Bowl. Canadian football teams play for the Grey Cup. That’s right: the Grey Cup.

But I think the best example of our obsession with all things morbid is to be found in our cinema. In many ways, the Canadian movie industry is merely an adjunct of the American movie industry. Americans make movies in Canada to take advantage of our tax breaks and our devalued currency, earning the Canadian film community the nickname Hollywood North. I don’t think this name is accurate. When Canadians make movies about Canada, our movies tend to be a little morbid. Whereas I like the nickname Hollywood North, I think a more apt name for the Canadian film industry is Cinema Bleak. Our movies deal with tragedy in a way that would even make Swedes say, “Come on, Canada, lighten up.”

The classic Canadian film Goin’ Down the Road, released in 1970, is about two naive Bluenosers (Nova Scotians) headed to Toronto. An abridged Wikipedia description of the plot reads as follows: Pete and Joey drive from Nova Scotia to Toronto with the hope of finding jobs. They find minimum-wage jobs at $2 an hour. They turn their “good fortune” into a small apartment, where Joey decides to marry his now-pregnant girlfriend, Betty. His debt-driven lifestyle strains his finances. Pete and Joey get laid off. Unable to find work, with bills to pay and a baby on the way, they get caught stealing food from a supermarket on Christmas Eve. Then they pawn their colour TV and head west, leaving Betty and her unborn child in Toronto. Wow. Deeee-pressing.

The IMDB logline for the Canadian film Wedding in White (1972) reads as follows: “A father will do anything to protect his family’s reputation when his unmarried teenage daughter becomes pregnant because she was raped by her brother’s friend.” Super deeee-pressing.

The 1981 David Cronenberg film Scanners is slightly more upbeat. It’s a science fiction film about a man with unbelievable psychic powers who has the ability to make other people’s heads explode. The movie contains perhaps the most graphic head explosion since Abraham Zapruder’s 1963 film chronicling the Kennedy assassination.

The 1996 film Crash explores the world of “auto-eroticism,” wherein severely disturbed, numbed-out people can only get sexually aroused by being in car accidents. It’s a great film that plays on the old formula of boy meets girl, boy loses girl, boy gets girl into a car that goes over the guardrail, boy gets girl back in ICU. You know, that old chestnut. It’s dark. Fascinating, but dark.

But perhaps the greatest example of Cinema Bleak is Atom Egoyan’s 1997 film The Sweet Hereafter. Though based on an American novel, it took a Canadian to bring this so, so, so, so bleak story to a cinema near you. Wikipedia describes the plot of The Sweet Hereafter in the following way: “In a small town in British Columbia, a school bus skids into a lake, killing fourteen children. The grieving parents are approached by a lawyer, Mitchell Stephens (Ian Holm), who is haunted by his dysfunctional relationship with his drug-addict daughter. Stephens persuades the reluctant parents to file a class-action lawsuit against the state, school district, or other entity for damages, arguing that the accident is a result of negligence.

“The case depends on the few surviving witnesses to say the right things in court; particularly Nicole Burnell, a fifteen-year-old now paralyzed from the waist down. Before the accident, Nicole was an aspiring songwriter and was being sexually abused by her father, Sam (Tom McCamus).

“One bereaved parent, Billy Ansel, distrusts Stephens and pressures Sam to drop the case; Nicole overhears their argument. In the pretrial deposition, Nicole unexpectedly accuses the bus driver Dolores Driscoll (Gabrielle Rose) of speeding, halting the lawsuit. Stephens and Nicole’s father know she is lying but can do nothing. Two years later, Stephens sees Driscoll working as a bus driver in a city.”

I would have loved to have been at the pitch session for this film.

STUDIO EXECUTIVE: Hey, guys, what have you got for us?

FILMMAKERS: It’s a movie about a town in B.C.

STUDIO EXECUTIVE: B.C.? I love B.C.! I went fly fishing there two summers ago. What happens?

FILMMAKERS: Well, it’s winter. And a school bus full of children crashes into a frozen lake.

STUDIO EXECUTIVE: I love it! So, it’s a race to save these kids?

FILMMAKERS: Well, no. Fourteen of the children die immediately.

STUDIO EXECUTIVE: Oh…Do any of the kids live?

FILMMAKERS: A few, and we focus on one of them. She’s an aspiring songwriter.

STUDIO EXECUTIVE: A songwriter! I see where you’re going with this, fantastic! She has a song in her heart, and she’s finally going to have a chance to sing it!

FILMMAKERS: Unfortunately, she’s paralyzed from the waist down.

STUDIO EXECUTIVE: Oh. But at least her parents are happy that she’s alive.

FILMMAKERS: Yeah, except that before the accident she was being sexually abused by her father.

STUDIO EXECUTIVE: Gentlemen, I don’t like it…I LOVE IT!!! I think we have the feel-good hit of the summer.

The Sweet Hereafter is actually a fantastic film. It was nominated for two Academy Awards (Best Director and Best Adapted Screenplay), and it won the Grand Prize of the Jury at the Cannes Film Festival. But let’s be frank here: she’s paralyzed from the waist down and her dad molested her? Well played, Cinema Bleak, well played.

Another way to look at the question of who we are is to point out who we are not.

We are not American.

To talk about Canada without talking about the “You-Know-Whos” just south of us would be, as we say in Canada, “a bit mental.” Pierre Trudeau once said, “Living next to [America] is in some ways like sleeping with an elephant. No matter how friendly and even-tempered is the beast, if I can call it that, one is affected by every twitch and grunt.”

I LIKE TO THINK OF THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN CANADA AND THE UNITED STATES AS THAT OF TWO BROTHERS.

I like to think of the relationship between Canada and the United States as that of two brothers.

We both share the same mother, Britain.

Canada and the United States grew up in the same house, North America.

The United States left home as a teenager and became a movie star. Canada decided to stay home and live with Mother.

But why did we decide to stay home? Why didn’t Canada join the American Revolution in 1776?

The answer illustrates the fundamental distinctions between Canada and America.

During the American Revolution, some seventy thousand American colonists did not want to split with Britain. Instead, these American refuseniks, who later became known as United Empire Loyalists, chose to move to Canada because they saw the American Revolution not as a story of salvation, but merely as a mercantile-class tax revolt.

The Loyalists agreed that reforms needed to be made, but they were skeptical of this shiny new object called American democracy. This skepticism came from the fact that British colonists were already familiar with democracy—parliamentary democracy—going back some five hundred years to the Magna Carta. The British Petition of Right of 1628 had already guaranteed the sanctity of private property, and the British Bill of Rights of 1689 had established rules of search and seizure and granted citizens the right to bear arms. Democracy wasn’t new to them; they just wanted to stay within the system and have the system evolve. The Loyalists were not revolutionaries, they were evolutionaries, and the effect of their sudden and substantial influx to Canada can still be felt on the Canadian psyche today.

Canadians have much respect for the American Revolution and the framers of their constitution. However, some Canadians are mildly amused when those on the extreme right refer to “the framers” as if they were spacemen who landed in America with extraterrestrial knowledge, and not the progressive, intellectual, English human beings they actually were. The extent to which some Americans endow the framers of their constitution with superpowers illustrates America’s ability to fashion creation myths so strongly that even I, as a Canadian child, believed that democracy and freedom had never existed before 1776. But then again, in the 1960s and 1970s I learned American history from The Brady Bunch and Bewitched.

Girl Guide Cookies: In Canada, Girl Scouts are Girl Guides. American Girl Scouts “scout” the wilderness for new trails. Canadian Girl Guides “guide” people on already known trails. The elderly man in the wheelchair died, in front of those kids, eh? Yah, sad.

The only time Canada and America came close to becoming the same country was during the War of 1812, which, as I mentioned, Canada won. The War of 1812 was, in many ways, Canada’s War of Independence. While Canada and America did not become one country, we became like two brothers who live in the same duplex. The Canadians have the drafty top floor, the Americans have the preferred ground floor, the fun floor, so fun that they often forget that somebody lives upstairs (us).

Every country has certain people who are visionaries, who have the gift to make things. Often, these people are called strivers. In America, these strivers are celebrated—Thomas Edison, the Wright brothers, Steve Jobs, etc. In Canada, we have no tradition for cultivating, protecting, and ultimately celebrating our strivers. It’s true that much attention is given to Frederick Banting and Charles Best, the two Canadian scientists who invented synthetic insulin, but that’s the exception that proves the rule. It’s almost as if Canadian schools should have a strivers’ ed. program. This is a fundamental difference between Canada and America.

Not everybody has to be a striver. Canada does a very good job of trying to raise the standard of living of all its citizens. I think this is admirable and appropriate. However, those poor, tortured Canadian souls who are driven to innovate and make things don’t just have to endure the typical loneliness of genius, they also must overcome the inertia of a culture that continually asks strivers, “Who do you think you are?”

There is a sociological concept called the competence-deviance hypothesis, which states that people will overlook the deviant behaviour of an artist in proportion to how successful they are. To put it colloquially, “Sure, he looks crazy, but who am I to judge his deviant behaviour because, look, he’s successful.” The hypothesis goes further. It says that people don’t just tolerate the artist’s deviant behaviour, they believe that the artist’s success is because of the deviant behaviour.

Canada has no patience for the competence-deviance hypothesis. At the first sign of deviance, Canadians will tend to devalue even the most gifted person’s work, as if the deviant behaviour makes the work an ill-gotten gain.

There’s a word for people who need talent and normalcy to be congruent, and that word is provincial. Other countries have the tall poppy syndrome, but theirs has more to do with jealousy, whereas Canada’s tall poppy syndrome has more to do with an almost Calvinistic disdain for the flamboyant and the excessive. Because Canada is one of the most blessed, educated, peaceful, and tolerant countries in the world, I have great faith that the next generation of Canadians might very well be the first to abandon the tall poppy syndrome. We will go from “Who do you think you are?” to “Who do you want to be?” Imagine the explosion of creativity that would come from that.

I hope Canada will soon stop looking to others for validation. I grew up hearing over and over again that this or that was “Canada’s answer to…whatever” and that “whatever” was usually something American. The problem with “Canada’s answer to…” is that nobody’s asking. Canadian Paul Anka was not Canada’s answer to Frank Sinatra. Have you ever heard an American say that someone was “America’s answer” to anything?

Canadians complain about how hard it is to make culture, living next to the cultural powerhouse of the United States. I’ve always thought this was ironic. Surely it’s an advantage to be close to the culture that not only invented but mastered filmed entertainment. We should study American film production with the same fervour that martial arts students study Japanese masters. Los Angeles is the best place on the planet to make filmed entertainment. It’s not just Canadians who go down there; the whole world goes there. Even the Soviet filmmaker Eisenstein agreed that American movies were superior. The Englishmen Alfred Hitchcock, David Lean, Adrian Lyne, and Ridley Scott all made movies in America, as did the Pole Roman Polanski, not to mention the Austrian Otto Preminger. Ang Lee made The Ice Storm, portraying American type-A personalities, despite having grown up in Taipei.

Perhaps because we live next door to America, we wait for Hollywood to knock on our door instead of making our own movies about our own lives. We shouldn’t wait to be hired. We should just hire ourselves. We shouldn’t wait for Broadway, we should make our own stage. It’s been said that theatre is merely two planks and a passion. If that’s the case, then go to Canadian Tire and buy two planks. We shouldn’t wait to be “discovered.” We should discover ourselves.

WE SHOULDN’T WAIT TO BE “DISCOVERED.” WE SHOULD DISCOVER OURSELVES.

We should be our own cultural engineers. The difference between an engineer and a physicist is that the engineer doesn’t need to have done all his “proving math” before he begins building. Americans don’t wait for the “proving math.” Canadians often mistakenly believe that a flow chart of design must include a box called “foolproof” before we go into action. We’re failure-phobic. Americans are not. In fact, NASA doesn’t use the F-word; instead, they call failure “early attempts at success.” Canadians need to embrace the concept of “You’ll see it when you believe it,” and while there will be rejections, we should let the rejections inform us and not define us.

America is comfortable with achievement. Canada less so. I feel that this is a result of Canada not having a clear mission statement. It affects our confidence and it starts in a Canadian childhood.

Canadians are at a disadvantage when it comes to describing their childhood. There are no movies about growing up in Canada to which we can point as a shorthand. English people have Lord of the Flies, Harry Potter, Mary Poppins, or even Bend It Like Beckham. Americans have…anything by Disney. Canadians, on the other hand, got nothin’. Therefore, when I try to describe my Canadian childhood, I often feel like I’m describing a dream I had.

Try explaining to a non-Canadian The Friendly Giant. Or Mr. Dressup. Or Danny Gallivan. Or Howie Meeker. Or Stompin’ Tom. Or Don Cherry. Or Lanny McDonald. Or Eddie Shack. Or Cherry Lolas. Or the Food Building. Or the PNE. Or Le bonhomme de neige. Or Luba. Or The Forest Rangers. Or the Calgary Stampede. Or Dildo, Newfoundland. Or Lotta Hitschmanova. Or the Roughriders, and then, of course, the Rough Riders. Or St. Johns and St. John.

It was all a dream….Or was it?