|CHAPTER FOUR|

A Canadian Adulthood

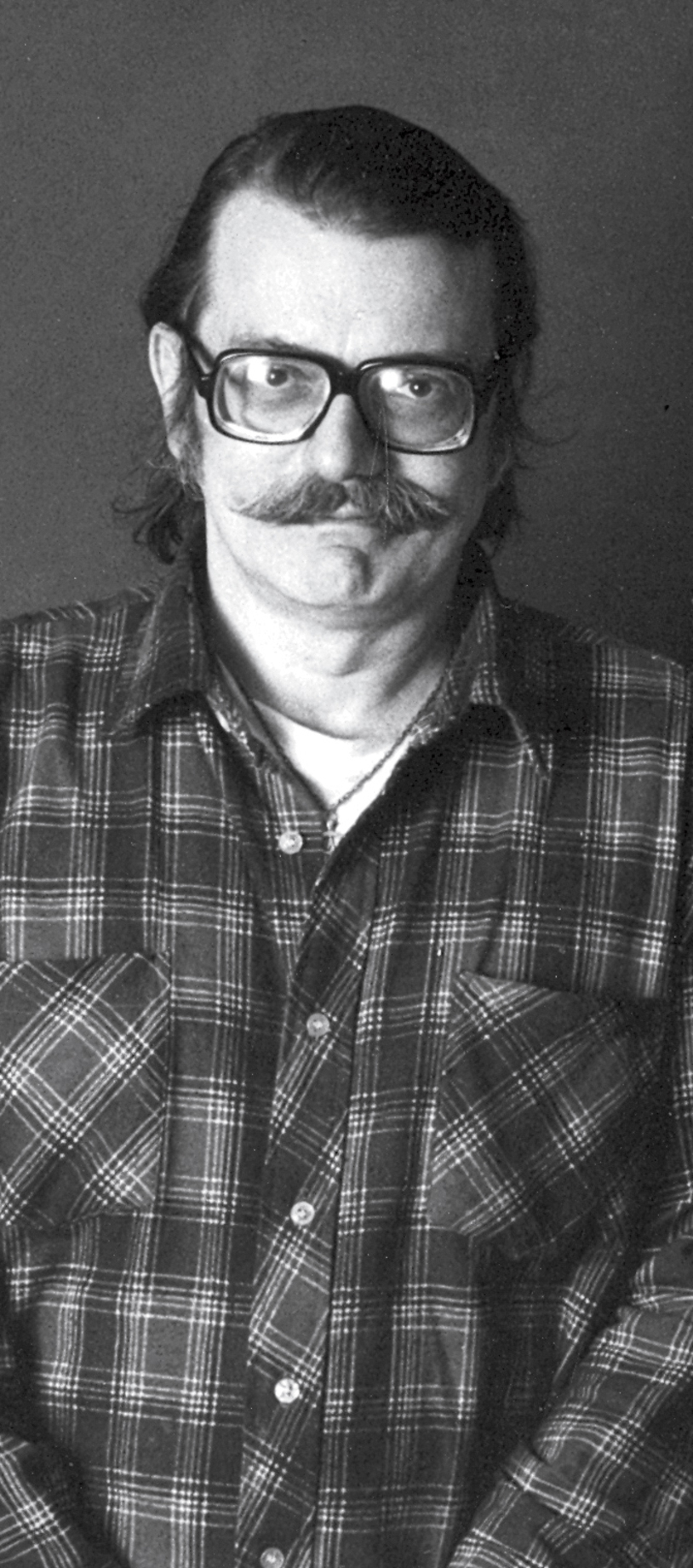

Me and my Mountie, “Don,” in my first apartment in Parkdale. Note the denim shirt, part of my Canadian tuxedo.

IN THE SUMMER OF 1982, I was 19, and I had just been hired by the Second City Theater Company. I moved out of my family’s home in Scarborough and got my first downtown apartment, which was in a rundown west-end Toronto neighbourhood called Parkdale. I had a room in a giant Victorian mansion filled with conceptual artists. My brother Paul lived there as well, and he introduced me to a world of artists and artistic sensibilities and the music of Brian Eno and Talking Heads. The artists in this house all had Canada Council art grants, and I would hardly say they were living in the lap of luxury. It was subsistence living, but it was cool.

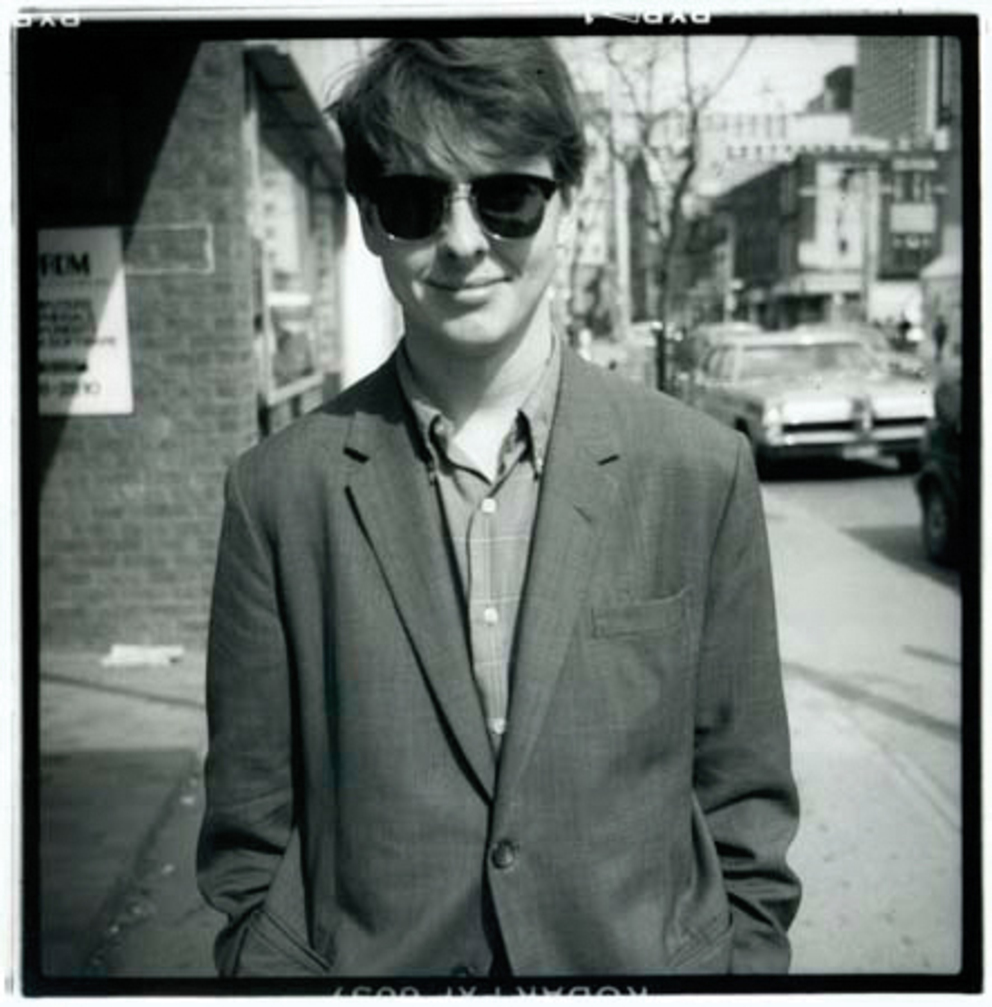

The Second City Touring Company Van, aka “The Van.” The smell of stale costumes, cheese popcorn, Tuborg beer, and alcohol flasks—it could be a bit cuttish.

Each day, I would take the streetcar all the way to the centre of town. At Queen and Yonge, I would go into the Eaton’s department store and, for good luck, I would rub the toe of the statue of Timothy Eaton, the store’s founder. His toe was brightly polished from other people rubbing it, and it stuck out over the plinth that the statue stood on, as if inviting you to rub it.

Not to “luck-shame,” but why was his toe sticking out like that, begging to be rubbed?

I needed luck, because I didn’t know what the hell I was doing. My fellow performers in the Second City touring company were seasoned veterans. Each of them was insanely talented. The first part of the show was scripted, usually tried-and-true sketches from the vaults of Second City in Toronto and Chicago.

Performers at Second City tended to fall under various archetypes: the Big Guy (John Candy, Chris Farley); the Smart Guy (Bill Murray, Dan Aykroyd); the Irish Girl (Catherine O’Hara, Tina Fey—though she’s not Irish); the Jewish Girl (Elaine May, Gilda Radner); and then my archetype, the Small Guy with Lots of Energy. Martin Short was my patron saint.

The second part of the show, the improv set, was where I shone. I wasn’t very strong with scripted material, and certainly not scripted material that I wasn’t connected to.

At that time, my friend Dave Foley was doing brilliant, almost experimental sketch comedy with the Kids in the Hall. They were great improvisers, but they didn’t care much for the form. Dave Foley would often say, “Improv could do with a rewrite.” Their material was personal, fresh, and thrilling. They were doing what I wanted to do, but I was very grateful to be in Second City and my mind was blown that being a professional actor was my “job.”

SECOND CITY WAS KIND ENOUGH TO LET ME BE NOT-VERY-GOOD FOR A LONG TIME.

We mostly toured the hinterlands around Toronto, and in the summers there was a permanent gig at a lodge near Algonquin Park—a provincial park in Northern Ontario, roughly a quarter of the size of Belgium. This was the beginning of my “Hamburg period.” Second City was kind enough to let me be not-very-good for a long time. My fellow performers taught me well—some of them took me under their wing, because I was a chick that had just left the nest, not yet skilled enough to fly.

Amongst the many gifts I received from the Second City touring company was the opportunity to see the rest of Canada. Until then, other than Quebec, I hadn’t seen much of the country.

I remember one particularly eventful cross-Canada tour. We went from Newfoundland on the East Coast to Vancouver on the West Coast. Four thousand miles. Newfoundland was beautiful, and my mind was blown by the Newfie accent, so much so that, after the show in St. John’s, I went to a nightclub and pretended I was Scottish for a whole evening, ashamed at how boring my Toronto accent was compared to the Newfie brogue.

I HAD ONE OF MY BEST SHOWS OF THE TOUR. IT WAS ALSO THE SPOOKIEST SHOW.

The next show was in Halifax, Nova Scotia. I love Halifax. I had the best salmon tartare and Caesar salad of my life at one of those eighteenth-century restaurants down by the beautiful harbour. For a city of its size, it always feels like it has as much nightlife as New York. I had one of my best shows of the tour. It was also, however, the spookiest show.

After the scripted portion, I came out to introduce the improv set. The crowd was electric, but as I was onstage explaining something, a deep, resonant, booming voice from the crowd said, “You have wonderful energy, Michael.” The voice sounded like Vincent Price—it was otherworldly.

It was so scary that it made the audience laugh. I wasn’t famous, so I don’t know how “The Voice” knew my name. I said, “Wow! We have a contingency from Hades here this evening.”

The Voice continued, “You really do have great energy, Michael.” This time, the audience did a collective “Ooooh.” He was scary.

I finished the show, and I was backstage talking to a couple of lovely ladies, when The Voice came backstage. It was attached to a man in his forties, six-foot-five, black ringlets of long, flowing hair, heavy black eye makeup, and black clothing. “You really do have wonderful energy, Michael,” he said in his booming voice.

The members of my cast scattered. The well-wishers backstage froze in their tracks. I said, nervously, “Thank you…”

He continued, “You know, Halifax is one of seven spots around the world that collects energy.”

“Oh yeah?”

“So, we are particularly attuned to those that…possess…energy.”

“Right on.” At that moment, I noticed a large pendant around his neck. It was an inverted pentagram, the upside-down star shape favoured by devil worshippers. My heart stopped.

“I’ll leave you now, Michael. Blessed be, Michael. Blessed be.” He didn’t walk out of the room so much as hover backwards. People started to genuflect. Strangers came up to me wondering if I was “OK.” Of course, “Blessed be, Michael” became my newest catchphrase with the rest of the cast.

In Thunder Bay, Ontario, the cast conspired to call my room at three o’clock in the morning and every hour afterwards, using devil voices, saying, “Could I speak to Michael, please? I need some of his energy.” I would get handwritten messages, slid under the door by hotel staff, that just said, “You have a call from: Blessed be.”

Thunder Bay is the home of Paul Shaffer, best known as the bandleader on David Letterman’s talk show. I spent a day taking Polaroids of Thunder Bay. I went to the Finnish neighbourhood, where I had a sauna and the Finnish equivalent of a smorgasbord. In the bay is a magical island called the Sleeping Giant, which looks exactly like a sleeping giant.

We then went on to Winnipeg. Winnipeg had more hipsters per capita than any other city in Canada. Home of the world-famous Royal Winnipeg Ballet (government subsidized), the “SoHo” of Winnipeg was an unexpected bohemian delight. Of course, I ate perogies—it’s the perogy capital of Canada. I also experienced the corner of Portage and Main, literally the coldest corner in Canada that isn’t in the Arctic. Cold. Impervious to the warming effects of several dozen perogies and half a bottle of vodka.

Next, we drove through Saskatchewan—Big Sky country. The flattest place I have ever been. If you stand on a five-step platform, you can see an extra mile. They had to put bends in the road so that people wouldn’t fall asleep driving at night. We played a town in Saskatchewan called Swift Current, which the locals call Speedy Creek. After the show, I went to a Native Canadian bar whose house band was called the FBIs, which, upon inquiry, was revealed to stand for the “Fucking Big Indians.”

My castmate, though in his thirties, was still a juvenile delinquent. He started to get mouthy and tried to hook me into a fight with the FBIs. I apologized for my asshole Toronto friend, which they accepted. I went outside to get some air. My castmate was given the bum’s rush by a Native Canadian who, I swear, was seven-foot-five. My castmate proceeded to steal a cab and implored me to get in, because that would be our ride home. He leaned on the horn, causing the entire bar to empty, including the owner of the taxi. The castmate hit the gas and left me with these angry locals. The look on my face saved my life, because the entire town burst into spontaneous laughter. They called the cops and invited me in for one more drink and a grilled cheese sandwich. The car was retrieved and the cab driver brought me home.

We went to Regina, Saskatchewan’s capital, and had a great show. (Americans never believe that there’s a town called Regina.) In fact, in the show, we had a word association scene:

DOCTOR: Mother?

PATIENT: Father.

DOCTOR: Love?

PATIENT: Hate.

DOCTOR: Vagina?

PATIENT: Saskatchewan.

That’s the sketch, people. That’s it, and it killed, night after night.

And then, in the words of the Guess Who, we went running back to Saskatoon, which, as the name would suggest, is in Saskatchewan. We were two days in Saskatoon. On the free night, I decided to check out the University of Saskatchewan theatre department’s year-end production of the Restoration comedy The Country Wife. This beautiful theatre at the University of Saskatchewan was packed with Saskatonians. The snobby Torontonian in me had low expectations—it was Saskatoon, after all, the sticks. Lo and behold, this little university in the middle of Canada knocked it out of the park. The acting was thrilling, the stagecraft was brilliant, the lighting was artful, student musicians played authentic baroque music live onstage, and it was funny! It was one of the greatest nights of theatre in my life. Thank you, Canadian government. Money well spent.

IT WAS ONE OF THE GREATEST NIGHTS OF THEATRE IN MY LIFE.

That night, I treated myself by staying at the Bessborough Hotel on the Saskatchewan River in downtown Saskatoon. The Bessborough is one of the Canadian railway hotels—huge, majestic, castle-like, with triangular copper roofs, like the Canadian Parliament buildings in Ottawa. Pure Canadiana. One of the nicest hotels I have ever stayed at.

In Calgary, we had another fantastic show. And afterwards, I wanted to go out to experience one of the famous wild bars on Calgary’s Electric Avenue. But I was starving, so I went back to the hotel diner on the ground floor. As I took a seat at the counter, I felt a pair of eyes on me. It was a beautiful lady staring at me with such intensity that a sheen of sweat broke out over my forehead. I was with two other cast members who assured me that, due to the bizarre attention I was receiving, I was definitely going to “get lucky” here in Calgary.

She approached. She was stunning. She was French Canadian and said to me, “Allo, Michel. I louved de show.”

“Ooh…thank you…” In my head I screamed, How does she know my name?!

“You know, Michel, you ’ave wonderful energy.” She spread open her vest, which I hoped might be so that she could show me her ample cleavage. But instead she revealed a pendant. A pentagram, just like that of The Voice in Halifax!

My two cast members got up and ran out of the diner, screaming, “Too much evil! Too much evil!”

Then the beautiful French-Canadian satanist said, “I don’ t’ink dey could ’andle your energy.” She put her hand on my thigh, which I would later claim left a scorch mark. “Do you want to go to anodder club? I know a great club where you’ll feel welcome.”

THEN THE BEAUTIFUL FRENCH-CANADIAN SATANIST SAID, “I DON’ T’INK DEY COULD ’ANDLE YOUR ENERGY.”

I lied and told her that I was a gratefully recovering alcoholic, and that, should I have one more drink, I would need yet another liver transplant. She left and, as she hit the cold Calgary air, turned back and said to me, “Blessed be, Michel. Blessed be.”

I got no sleep.

The next night was Lethbridge, Alberta. We drove past the hoodoos—a unique geological formation of wind-worn rocks that form mushroom-capped columns of stone that create the illusion of a vast army of “rock people” (I’m not talking about the KISS army). I had barely heard of Lethbridge, and I was struck by the variety of terrain in my home and native land.

And then we drove through the Crowsnest Pass in the Canadian Rockies. The Canadian Rockies are the most beautiful place on the planet Earth, truly magical, truly virginal, almost a joke. We got to Nelson, British Columbia, a pristine town nestled amongst breathtaking mountains, brilliantly preserved from its heyday of the Silver Rush (of course, Canada had a second silver rush in 1976 at the Montreal Olympics).

We played the art college in Nelson. The audience was filled with art students, and after the show I got drunk and started to dance with one of the art tarts at the school. She was older than me, and very forward—which, because I was shy, was a godsend. It was a humid dance floor at the after-show party. Before the tour, I had bought a new leather jacket. The Art Tart whispered in my ear seductively, “Do I smell leather?”

I replied earnestly, “Sorry, it’s new.”

She found my innocence adorable, and whispered, “Do I smell handcuffs?”

I immediately spit out, “No, you do not smell handcuffs.”

Then she said, “Pity. I’m going to get us a drink.” She went across the room to her six-foot-five biker boyfriend, and from afar I could see that she was asking him for money to buy me a drink. The biker boyfriend shot me a dagger, so I took off into the next room and hid. Consequently, I missed the troupe van back to the hotel, which was two miles away. I looked in my wallet. I had seventy-five cents. I was going to have to hoof it.

Drunk as a lord, I began to stumble home along the wooded, unlit highway. About a mile in, completely alone, I heard a rustling behind me, and I saw the reflective glow of a wild animal’s eye. It was a wolf. My heart started to pound. Then there were twelve wolves. I started to lightly drunk-jog toward the safety of the hotel lights in the distance. All at once, the wolf pack’s ears shot up and their nostrils flared, presumably because they too could smell leather. Then they started to jog after me with the princely gait of an accomplished predator. Seeing this, I started to run my fastest. And because of the eleven-plus Molson beer in me, I was now vomitous—or as we say in Scarborough, I had a honk on deck. I started to whimper. So this was how I was going to die…torn apart by a pack of wolves in the wilds of British Columbia. At least it would be a Canadian death.

IT WAS A WOLF. MY HEART STARTED TO POUND. THEN THERE WERE TWELVE WOLVES.

Miraculously, a car with one headlight approached from the other direction. As if out of a 1950s sci-fi movie, I ran to the middle of the road, frantically waving my hands to flag down the car. Mercifully, the one-headlighted car stopped and let me in. To my horror, the driver had one eye. One headlight, one eye. Now I was really freaked out. Were they his wolves? Is this how he gets his prey? The conspiracy, of course, would have been confirmed had the wolves only had one eye. He pulled a U-turn to take me to my hotel. Behind us, I saw the faces of disappointed wolves. My cycloptic saviour asked me, “Are you from Toronto?”

I said, “Yeah, how did you know?”

He said, “Only a dipshit from Toronto would walk along this road.”

As we arrived at the hotel, the troupe was already loading the touring van to head to the next show. I curled up in the back with the costumes, made myself a little nest, and slept for eight hours.

I woke up in Vancouver. We did a show that night. It was a great house, and as is the case when you’re twenty, I was up for going out again. The stage manager of the theatre recommended a bar downtown. Mysteriously, he insisted that the bar was “perfect for me.” I wasn’t sure if he thought I was gay, or a socialist, or into karaoke, but I went to this “perfect for me” bar with a couple of castmates.

The address took us to an unmarked building with a set of stairs leading down to a basement bar door, behind which we could hear muffled yet slightly sinister music. One cast member said, “Fuck it, Myers, I’m not going in there,” and left for the hotel. I opened the door. On the back wall of the bar…was a giant pentagram!! The remaining cast members ran away, again shouting, “Too much evil!” On the bar itself was a goat’s head. The band was called the 666s. I’m guessing they were the house band of the beast. I stayed and had a drink. I don’t know what possessed me.

I have fond feelings for Vancouver. I got over my grudge about them booing Team Canada during the ’72 Summit Series once I remembered that Vancouver was the home of Greenpeace. Good work, Vancouver. Good work, Greenpeace, you do us proud.

Vancouver is stunning. Those two beautiful peaks, the Lions, reminded me of Bruce Cockburn’s “Wondering Where the Lions Are.” I love that song, especially his reference to the sweet smell of the fir trees, which I had smelled the night before as I was being chased by wolves. As much as Vancouverites often say they hate Torontonians (why?), Torontonians really love Vancouver. Our love, of course, begins with The Beachcombers, but for me, it extends to the Vancouver Canucks’ side-stick logo through to the people of Vancouver themselves. Like me, they’re very proud to be Canadian.

Well played, Vancouver, well played indeed.

The troupe took the ferry over to Victoria to perform at a theatre festival. Victoria is the architectural proof of the saying that there is no one more English than an Englishman who no longer lives in England. Every Englishman who’s been there wishes actual England looked like Victoria. We had arrived in the morning, and as it was a festival of the performing arts, I took the time to broaden my horizons and take in a modern dance performance. I was twenty, always the youngest in the cast, but the dancers in this troupe were all my age or younger. Beyond the beauty of the girls in the troupe, I was struck by the beauty of modern dance itself. A love affair with dance was born that day, and old Twinkletoes here silently vowed to himself to try to include dance in everything he would do.

Hands down, British Columbia is Canada’s most beautiful province. Don’t tell Toronto, but when people ask, “Where should I go in Canada?” I say British Columbia.

When I got back home to Toronto, a Second City touring company castmate, Christopher Ward, had been offered twelve hours a week of television time on a local Toronto station called CityTV. CityTV had built its reputation by showing pornos on Saturday nights, which they called the Baby Blue Movie. Every Saturday, I Jedi mind–tricked my parents into going to bed so that we could watch the Baby Blue Movie. So it was no surprise when this maverick station, CityTV, decided to create Canada’s version of MTV, with Christopher as its first VJ.

IT WAS TIME TO WAKE UP AND SMELL THE DOUBLE DOUBLE.

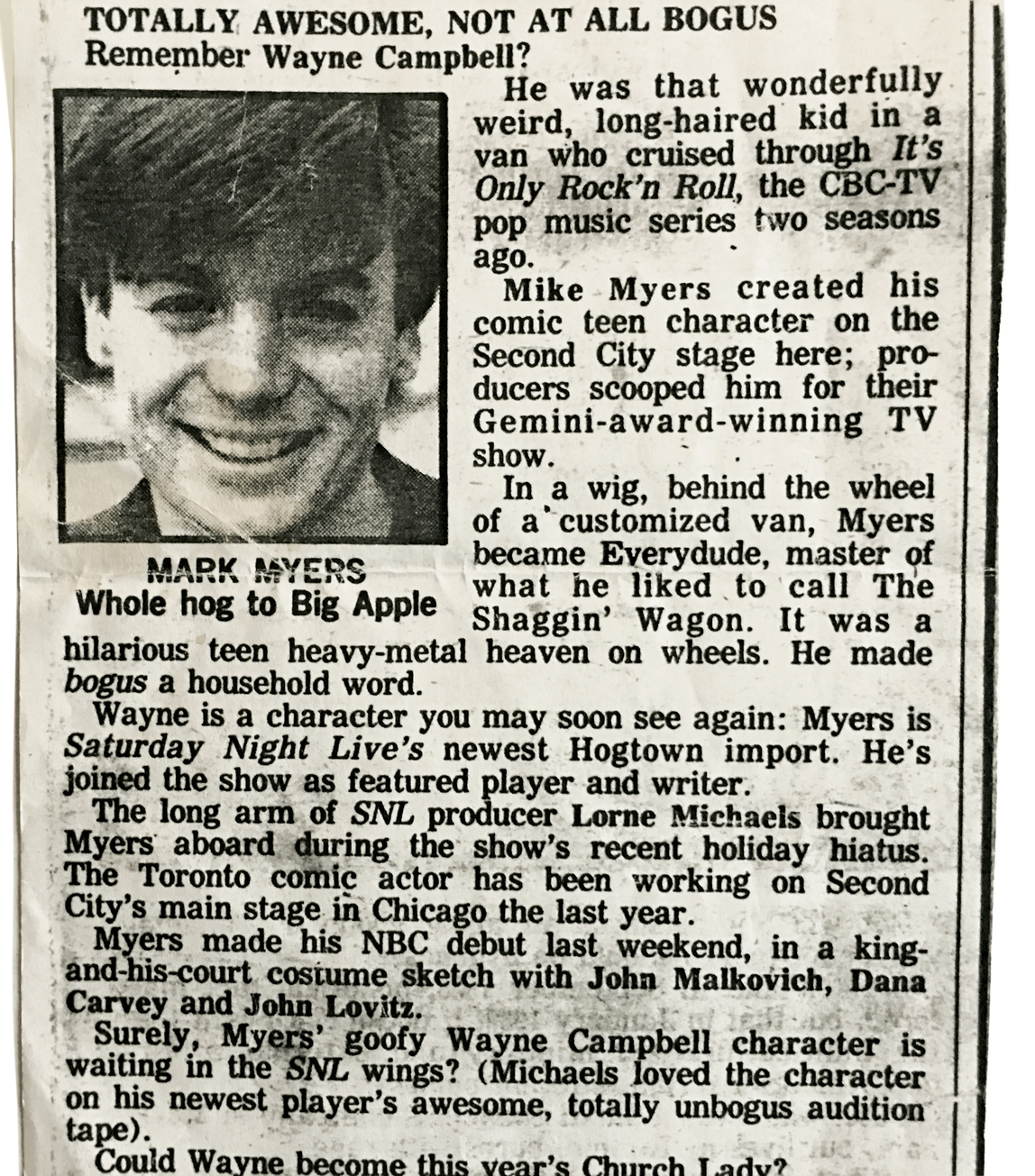

Christopher called me up and asked me to be a guest on his show, City Limits, which aired midnight to 6 a.m. on Fridays and Saturdays. I decided to do Wayne Campbell. I would pretend to be Christopher’s cousin from Scarborough who had gotten past security and crashed the show. It was successful. So successful that some Canadian viewers complained that they were letting ruffians from Scarborough on Canadian airwaves. They didn’t know Wayne was a character—high praise indeed.

Christopher is one of my closest friends. He would go on to write the Alannah Myles smash hit “Black Velvet,” and he and I would team up again in Austin Powers, with Christopher playing a member of Austin’s band, Ming Tea.

It was 1984, I had spent two years in the Second City touring company, which was the minor leagues of Second City. The mainstage company was the brass ring, and if you had been in the touring company for as long as I had without a hint of promotion, it was time to wake up and smell the double double: you’re not getting promoted. So I quit.

I was twenty-one, and I had no job and no future prospects in Canada. My friends the Kids in the Hall were coalescing into a cutting-edge sketch comedy troupe, but they weren’t hiring. I had made a deal with myself that I would never go to either New York or Los Angeles unless I had a job that required me to go there.

Because my parents were English, I could get British citizenship and I could work in England. I had long been a fan of British comedy—Monty Python, Peter Cook and Dudley Moore, and, of course, Peter Sellers. The little voice inside my head said if I didn’t move to England now, I never would.

So in 1984 I moved to London and left Canada behind.

I had no regrets about leaving Canada. I had been lucky enough to work as a professional actor, and I had gotten to see all of the country. I wondered if Canada would still become the Next Great Nation, as had been promised between 1967 and 1976. And although Trudeau was still my prime minister, I had gotten the sense that the spirit of Confederation, of Expo 67, of the ’72 Summit Series, and, frankly, of Trudeaumania itself had become a thing of the past. I held out hopes that Canada would still “make it.” Nothing was being said to the contrary. It’s just that nothing was being said. And even if Canada did become the Next Great Nation, I wouldn’t be there to see it.

Canada is cold, but England is colder. It’s a damp cold that gets into your bones, and you are never quite warm. Except if you’re in a hot bath, and even then, after ten minutes in a British hot bath, you find yourself cold in a hot bath. My first four months in England were more like an extended vacation, but my Canadian savings were starting to run out, and if I didn’t get a job soon, I would have to move back to Toronto with my tail between my legs.

One day, I came across a sign in front of the famous Gate Theatre in Notting Hill. Playing at the Gate for the next three weeks was a sketch-comedy revue called Feeling the Benefit. The cast of Feeling the Benefit were all recent alumni of the Cambridge Footlights. Being a student of English comedy, I knew that the Cambridge Footlights was a theatre club at Cambridge University, which had put on an annual comedy revue since 1883. Past members of the Cambridge Footlights had included my heroes Graham Chapman, John Cleese, and Eric Idle, who went on to form Monty Python. But that was long ago. The cast of Feeling the Benefit was just a group of young, unknown Footlights graduates who were trying to make a name for themselves by putting on this show. The sign also said that the Gate Theatre was hiring people for the box office, so I went upstairs and got a job working the door at the theatre.

The next day, I showed up to the Gate Theatre for my training. It became clear that I didn’t know British currency. There were half-pence coins, one-pence coins, two-pence coins, five-pence coins, twenty-pence coins, fifty-pence coins, and one-pound coins, but also at that time one-, five-, ten-, and twenty-pound notes. Also, there was a thing called concessions. Not a concession stand selling food, but ticket-price concessions for things like old-age pensioners and the unemployed, who needed to show their UB40 unemployment card to get the discounted ticket price. It was the 1980s and Britain had massive unemployment, so most people were on the dole, which meant long delays as I looked at documents I’d never seen or heard of before.

Because of my Canadian accent, my boss assumed I was mildly delayed. She spoke slowly, over-enunciating, as if I was not only mentally challenged but deaf as well. As if that weren’t bad enough, there was a shortage of chairs at the theatre, and so I was forced to sit at the box office table in a prop wheelchair, suffering the unnecessary sympathetic looks of the theatre patrons as I invariably got their change wrong.

I saw Feeling the Benefit. The cast were all young, confident, good-looking, painfully intelligent, and they spoke with posh accents. It was very funny, very clever, and, to my surprise and delight, very loose and silly. They did amazing American accents. At the end of the show, they did a Quinn Martin–type epilogue, with a perfect American announcer voice saying something like, “Epilogue: Bill Smith was sentenced to twenty-five years in a federal penitentiary. Which is American for jail.” It was hard for me to watch the show because I wanted to be onstage performing instead of working in the box office, making ten pounds a night, freezing my ass off in the unheated lobby of the theatre, sitting in a prop wheelchair and watching other people follow their dreams.

The cast was nice. There was one woman in the show, Morwenna Banks, who was fantastic. I would meet her again later in life, when she was briefly on Saturday Night Live. But I now hear Morwenna Banks every day, because she’s the voice of Mummy Pig in the British children’s show Peppa Pig, which my three young children are obsessed with. But I digress.

Another cast member of Feeling the Benefit stood out: Neil Mullarkey. He was funny, smart, had a great physicality, and he was very likeable. There are performers you admire, performers you like, and performers you both like and admire. Neil was a performer I both liked and admired. Over the run of the show, I got to know the cast a little, and from time to time, I was able to make them laugh.

Morwenna Banks. I’m a fan and so are my children.

After the show, I would sit in my prop wheelchair, cashing out, and as the cast left to get a drink, I would often shout after them, “Great, walk away! Wish I could!” And then I would roll myself to the top of the stairs and yell down at them, “Must be nice, assholes!” And then, in mock desperation, “Don’t leave me!” It would always get a nice laugh, and somehow, it meant more to me that I was getting a laugh from smart English people. But that’s just my Canadian low self-image.

On the last night of the three-week run, Neil Mullarkey invited me to join him and the cast for a drink at a pub. I finished cashing out and headed over. Mullarkey asked me how I’d gotten to England, and I told him about Second City. He had heard about Second City and said in his very posh accent, “If you’d been a professional comedian at Second City, why on earth would you come to London?” I told him I wanted to be in the land of Python and Peter Sellers. He said that at the moment, there was a booming alternative comedy scene, which meant there were plenty of places to play. I explained to him the Queen Street comedy scene in Toronto: places like the Rivoli, the Beverley Tavern, and the Cameron House.

I WAS UNSURE OF WHETHER I SHOULD PERFORM WITH A CANADIAN ACCENT, OR IF I SHOULD TRY TO ADOPT AN ENGLISH ACCENT.

He showed me a copy of Time Out magazine, the magazine that, amongst other things, listed all the comedy venues in London. There were easily twenty-five places to play. He pointed out that if you got enough material together, you could do two shows a night, every night. I was amazed. He asked me if I wanted to be in a double act with him. The next day, I quit my job at the Gate Theatre.

I started to write material with Neil, but I had no idea whether English audiences would like my comedy. I was also unsure of whether I should perform with a Canadian accent, or if I should try to adopt an English accent—I could already do Liverpool and Scottish dialects, but that wouldn’t match Mullarkey’s accent. Using my box office money, I decided I would take three elocution lessons at the Central School of Speech and Drama, to learn Neil Mullarkey’s accent, which is the posh southern English accent, like the Queen’s, that is called Received Pronunciation. During the first lesson, we went through the twenty-one vowel sounds of Received Pronunciation. Right away, my snobby English speech teacher stopped me and said, “I can’t in good conscience take your money.”

I said, “Why? What’s wrong?”

He said, “You’re never going to learn this. It’s your horrible Canadian accent. The monotonous drone, the ridiculous overstressing of final Rs, the grotesque diphthong on the vowel sound of the word out. If you spent several lifetimes trying to speak properly, your Canadian nasal twang would fail you every time.”

I was devastated, but Scarborough kicked in. As I left his office, I said, “Thank you for your time, but may I ask you one small favour?”

“What?” he said curtly.

I said, “Can you please go fuck yourself? I happen to like my Canadian accent.”

Of course, I didn’t say that to him. I wish I had. But I did think it, an hour later, while standing on the subway platform. It was a perfect example of the French expression l’esprit d’escalier, which means “spirit of the staircase.” In France, every building’s concierge has a window in the front lobby. As a tired tenant comes home from work, he passes the concierge, who invariably says something snarky. Exhausted, the tenant doesn’t have a comeback until halfway up the staircase, far too late for a timely rebuttal. Thus, a retort come too late is the product of l’esprit d’escalier.

What was all the more alarming to me was that I had actually thought that assimilating into Britain would be a breeze for me. I’m of British heritage. Growing up, I ate English foods, listened to English music, watched English TV shows, watched English soccer (Liverpool, of course). My parents had English accents, with my dad having one of the strongest and most recognizable—the Liverpool accent. But nothing makes you feel more Canadian than moving to Britain. Even more than moving to America. We can “pass” in America. Not so in Britain.

British culture is so impenetrable that, during World War II, even the German spy service, the Abwehr, were unable to successfully infiltrate British society. How, for example, would you make sense of the word Leicester? Would you pronounce it LESS-ter? Or the last name St. John-Stevas? Would you know to pronounce it sin-jin-STEE-vas? The last name Beauchamp is pronounced BEACH-em. Ich gebe auf! (I surrender!) In England, the second you open your mouth, you give away all your private information, rather like Facebook today.

Within a few months of living in a West London flat that was so cold you could hang meat in it, it became evident to me that assimilation was impossible and I would have to perform in my “Canadian nasal twang.” So Neil Mullarkey and I created material for our imaginatively named double act, Mullarkey and Myers. I would be the Canuck and Neil would be the limey.

The London alternative comedy circuit in the 1980s was a vibrant, cutting-edge, mixed bag of eccentric, experimental, mostly political sketch troupes, singer/songwriters, and standup comedians. It was very anti-Thatcher and anti-Reagan, very pro–Labour Party. Hugh Grant started on the alternative comedy circuit, as did the cast of the show The Young Ones, and Jennifer Saunders, known for her role in Absolutely Fabulous.

Pretty much any successful British comedian that you see is likely to have performed at one time on the London alternative comedy circuit.

I was Canadian, not terribly political, and the audiences I played for while in the Second City touring company were genteel by comparison. But I was going to throw my hat into this ring in the form of Mullarkey and Myers. That is, if I could get my hat into that ring. It was no small feat.

In a weird way, my being Canadian was an asset for breaking into the London alternative comedy circuit. There were rules—Canadians love rules, and have a Job-like patience for arcane systems. And London had a system.

AS A NEWBIE YOU GOT THE WORST SLOT: YOU WOULD HAVE TO GO ON FIRST IN FRONT OF A COLD, NOT-YET-DRUNK-ENOUGH MOB.

In order to get a foothold into the London alternative comedy circuit, new acts, like ourselves, had to get booked in one of the smaller venues, usually clubs above pubs, on the outskirts of town. The crowds were small, typically about ninety people. As a newbie, you got the worst slot: you would have to go on first in front of a cold, not-yet-drunk-enough mob. The promoter would only give untested acts like ours five minutes of stage time, which is not nearly enough time to win over a crowd. And you did all of this for free. If you survived, the promoter asked you back, giving you a ten-minute set, this time for a whopping ten pounds. No venue, large or small, in the centre of town would even deign to meet you until you could show them proof of bookings you had earned in the hinterland. We clipped out all our Mullarkey and Myers listings from the back of Time Out and made photocopies, our calling card.

Mullarkey and Myers’s first ten minutes of material had to be geared to quickly winning over a cold, disinterested, political comedy–loving, America-hating crowd.

What we couldn’t fix about ourselves, we featured. My Canadian (American-sounding) accent was one of them. In our first sketch I played an over-the-top American character and addressed the audience directly.

The British audience did not know what to make of me, but they knew my accent was authentic—I talked just like Americans in movies. If I was English, I was fantastic at dialects; if I was American, they would be charmingly bemused as to why I was on the outskirts of London, performing my heart out to seventy hipsters in a room above a pub.

We did well. But not always. Sometimes there was nothing you could do to win over an English crowd. Remember, Britain is the home of the soccer hooligan. And British alternative comedy fans didn’t just heckle you, they humiliated you. As a Canadian, I didn’t know that audiences were capable of humiliating anyone. At Maple Leaf Gardens, if the opposing team scored a clever goal, Leafs fans would give them a polite round of applause. The British pub crowds, on the other hand, wouldn’t politely applaud; they wouldn’t even just boo you off the stage. They were more creative than that: sometimes they would hum you off the stage, or sing you off the stage, or sarcastically laugh you off the stage.

Me in front of Stonehenge. I hated that haircut. It made me look like Mowgli.

And one time, I was sarcastically encouraged…off the stage, with one prick being particularly adept at telling you exactly what you would have hoped to hear, except he was being completely sarcastic. In a loud, interrupting voice, he would say such haunting things as, “You’re doing a great job, Mike! You have a real future in comedy. A star is born. Keep it up, boys.” He got huge laughs, we got crickets, but my hat was off to him.

In time we gathered more material, playing longer sets and inching our way closer to the West End of London. I was making enough money that I didn’t have to move back to my parents’ house in Canada, which I took as a victory. I called them and told them I was working in a double act with a comedian named Neil Mullarkey, to which my dad responded, “What, was Bill Shenanigans not available?” At the end of the conversation, he told me he’d “had enough of my Mullarkey.”

Once we had enough material written, the days were free for me to sightsee. I went to the British Parliament buildings, to see how they compared to the Canadian ones. Ours are smaller.

Any time I started to feel homesick, I would go to Canada House in Trafalgar Square. They showed hockey games there. Believe it or not, that’s where I was the first time I saw Wayne Gretzky play! It was nice to hang out with Canadians, to hear my own accent, and to talk hockey. I casually mentioned to one of the people who worked at Canada House that I was on the alternative comedy circuit. He asked how I was doing for money. I told him the truth: I was getting by, barely. He asked me if I wanted to stuff envelopes there at Canada House. For two days’ work a week, I could make seventy-five pounds. It was such an insanely generous overpayment, which I later found out was really an elegant way for Canada House to help out struggling Canadian artists in London. I invited the people of Canada House to come see one of my shows, and as it was their mandate to support Canadian artists in Britain, they actually came! Once again, Canadian government to the rescue.

My Mountie “Don” made the trip to England.

In their honour, Neil and I wrote a sketch, parodying the movie On the Town. In that musical, Gene Kelly, Jules Munshin, and Frank Sinatra are sailors on shore leave in New York City. To send a special thanks to Canada House, Neil and I played two Mounties on shore leave in London. The third Mountie was played by a life-sized standee of a Mountie that we got from Canada House. Part of the fun was trying to have it be an all-singing, all-dancing trio, with one of them being two-dimensional. We changed the lyrics to the song “New York, New York.” Instead of “New York, New York, a wonderful town…,” we sang:

London, England, ain’t lookin’ shabby,

Tower bridge, Westminster Abbey.

If you get lost then go ask a…babby

London, England, ain’t lookin’ shabby

After a while, clubs would call us. Our fees and stage times doubled. We got booked at this massive club called Jongleurs at the Coronet in South London. It went great. They asked us back. Then we got booked at the Comedy Store in Leicester Square. This was the pinnacle. We were doing nine or ten shows a week, making the equivalent of five hundred dollars a week in cash, which I kept in a shoebox, like a drug dealer.

WE WERE DOING NINE OR TEN SHOWS A WEEK, MAKING THE EQUIVALENT OF FIVE HUNDRED DOLLARS A WEEK IN CASH, WHICH I KEPT IN A SHOEBOX.

One of the first things I noticed about the alternative comedy circuit in London was that there was very little improvised comedy. There were a few fantastic troupes, but there was no improv comedy scene, as there had been in Toronto. It occurred to me that there were very few people teaching improv in London at the time. I decided to supplement my income by teaching a class at the Comedy Store. To my delight and surprise, there was a great deal of interest in improv in the London comedy scene, and my classes were filled to the rafters.

Seeing the huge response to the improv classes, the Comedy Store decided to host a weekly improv night. Mullarkey and I, and several other comedians, founded the Comedy Store Players, the Comedy Store’s in-house improv troupe. The houses were light at first, but steadily grew.

This little experiment in improv that I co-founded has been running now for 31 years with the same cast, becoming the longest-running theatre show with the same core cast in the history of the English language. It is in the Guinness Book of World Records.

By now, Mullarkey and Myers had enough material to book a theatre at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival. The Edinburgh Fringe Festival is an annual summertime performing-arts festival. Doing well at Edinburgh put you into the next tier—perhaps the BBC would give you a show.

We booked a theatre and made tons of posters, which we flyposted everywhere. We did every possible promotional live show, even managed to get on the radio, and someone at the BBC did a filmed piece about us. We needed some deposit money for the theatre, and we had three-quarters of it. I approached Canada House, and they got us half of the remaining quarter. And, fantastically enough, Ontario House got us the last eighth. More big government! Hooray!

We sold out our two-week run and got a fantastic review in Time Out magazine. From there, I got hired to do voices for a couple of BBC Radio series. I was hired to do a Scottish accent for one of them. And in one of the greatest ironies of my life, BBC Manchester paid for my train ticket from London to Manchester and put me up in a hotel so that I could play a character that had a Liverpool accent in one of their radio shows.

Me in John and Yoko: A Love Story. I play a Western Union messenger giving John Lennon his deportation papers.

I managed to get a London agent, and I got called to audition for an American television movie being shot in London about John Lennon called John and Yoko: A Love Story. It was a small role—a New York Western Union messenger who was so influenced by John Lennon that he dressed exactly like him, granny glasses and all. The scene involved the Western Union messenger giving John Lennon his deportation papers. My agent suggested that I not tell them that I was Canadian, because American producers hated Canadians playing Americans in London productions. The Americans could always sniff out Canadian accents. I decided that I would tell them I was from Upstate New York.

I met with the director, Sandor Stern. In the room were twenty or so production people. As I read my part, Mr. Stern wrote something on a piece of paper. After I finished my audition he held up the piece of paper. There was one word on it: BEEN.

He said, “Read this.”

Without thinking, I said, “Bean,” using the Canadian pronunciation—not “Bin,” the American pronunciation.

“ ‘Bean?’ Do you mean ‘bin?’ Upstate New York, huh? Where?” he asked.

“Way Upstate New York. A little town called Toronto, Ontario.”

The entire production staff burst into laughter.

Sandor said, “It’s your lucky day, kid. I’m Canadian. You’ve got the job.”

I was working steadily. Mullarkey and Myers was continuing to get a following, and the Comedy Store Players were consistently getting full houses. One day, I got a call from a reporter at the Toronto Star. They wanted to do an article about Mullarkey and Myers. The angle was that a Canadian comedian was taking London by storm. I was doing okay but not quite that good. The article came out right before Christmas, and it was a love letter. (Thank you, Toronto Star.)

Coincidentally, I was coming back to Toronto for Christmas. During my phone calls back to Toronto, I began to have suspicions that my father was a little “off.” My family did not want to upset me, but they had suspicions that he might actually have Alzheimer’s. When he picked me up from the airport, I noticed his driving was “off.” My dad sold encyclopedias for a living—he had learned how to drive in the British Army, not just cars, but two-and-a-half-ton trucks. He was an expert driver. Something was wrong. On top of that, when we got back to Scarborough, he missed our exit. And as much as he tried to hide it, he was lost.

On one of the nights on this visit, I went down to the Second City mainstage in downtown Toronto. Many of my friends had by now been promoted to the mainstage, including Dana Andersen, who was a gifted Edmonton-born comedian. He invited me to do the improv set. Because I was now improvising twice a week with the Comedy Store Players in London, my improv skills were sharp. The show’s director, Jeff Michalski, was in the audience. I must have had a good show, because the next day, Jeff Michalski invited me to join the Second City mainstage cast full-time.

This was, at once, my dream come true and a nightmare. I had promised Neil Mullarkey I would go with him, one more time, to the Edinburgh Fringe Festival. And besides, things were heating up for Mullarkey and Myers in London. And Neil was my comedy partner. It was a marriage—not only did I respect Neil Mullarkey as a brilliant comedian, but I had come to love him as a brother. Neil is one of the good guys in a business often filled with not-so-good guys. I didn’t want to leave Neil; I loved the work we were doing, I loved the London comedy circuit, and he and I had built something very special together. But my dad was sick. If I went back to London, I knew that the next time I would see my dad would likely be in half a year, and in that time I might be returning to see a man who was half of what he once was. Fuck Alzheimer’s.

THIS WAS, AT ONCE, MY DREAM COME TRUE AND A NIGHTMARE.

Ultimately, this made me decide to accept the invitation to join the mainstage cast of Toronto Second City, but I told the producers I had to leave for three weeks in the summer to honour my commitment to Mullarkey and go to Edinburgh. In an act of generosity that I will forever be grateful for, they agreed to let me leave for three weeks in August. Thank you, Andrew Alexander. Thank you for hiring me the first time, the second time, the third time, and for letting me honour my commitment to Neil Mullarkey. You’re a class act, Mr. Alexander.

I went back to London to tell Neil that I had to return to Canada for my father. He took it well. He was disappointed, as was I, but he was very happy to know that we would at least have Edinburgh.

I did two shows at the Toronto Second City mainstage. One was called Not Based on Anything by Stephen King. For it, I was nominated for a Dora Mavor Moore Award, which is Toronto’s Tony Award, and the show won a Dora for Best Musical Revue. Our director was John Hemphill. He had been in the cast when I was in the touring company, and I consider him to be one of the best improvisers to have ever stood on the Second City mainstage. He was also a brilliant director who pushed me and the cast to be the best that we could be. He was hilarious, disciplined, and highly principled. I will always cherish the time we had together, shoulder to shoulder, trying to put together the best possible show, and then afterwards, shoulder to shoulder drinking many Molson Canadians.

Many was the night that John and I, after drinking in legitimate bars, would go to speakeasies, until even they closed, ultimately ending up at the Golden Griddle Pancake House on Jarvis Street, eating silver-dollar pancakes and drinking overly strong coffee, talking about comedy movies that we loved, as the blue of dawn warmed up the summer day. Fantastic memories. Not a care in the world, except that the show would be great. Thank you, John Hemphill.

I would walk home on those blue mornings in Toronto. Never once did I worry about crime. I had the presence of mind to realize what a great thing it is, to live in a safe country. Other countries talk about freedom, but the freedom to walk home at night, knowing that the chances of being attacked are slim to none, is perhaps one of the greatest freedoms. There is also great freedom in living in a culture that isn’t particularly angry. But a lack of anger does have its downside. Inversely, necessity, or scarcity, can often be the mother of invention or industry, respectively. Before I left for England, I had a sense that Canada had drifted away from its mission of urgently forging an identity. When I returned from England, an even deeper malaise had set in. Canada didn’t seem as Canadian. And in response to that, my work became more Canadian.

I HAD A SENSE THAT CANADA HAD DRIFTED AWAY FROM ITS MISSION OF URGENTLY FORGING AN IDENTITY.

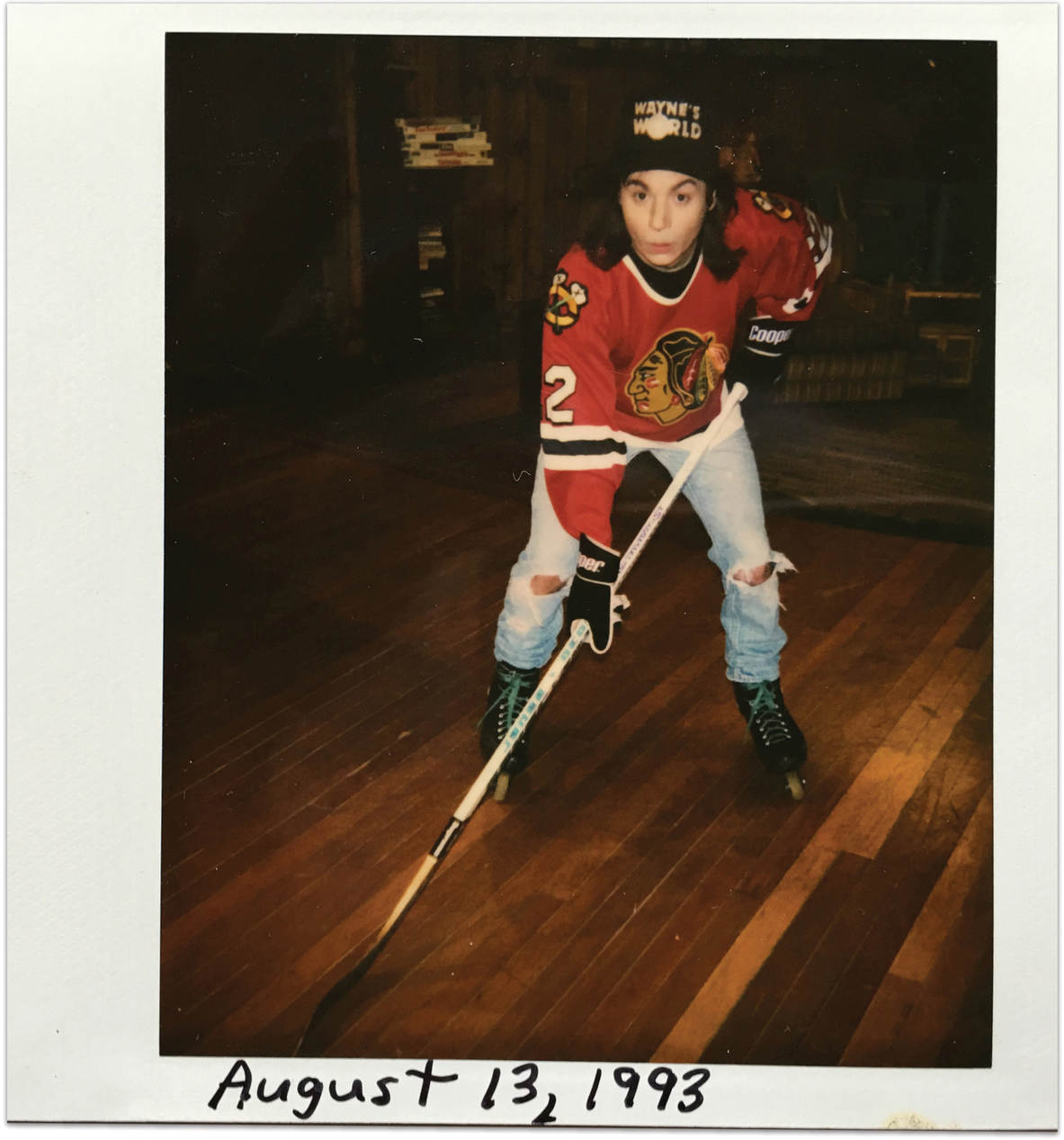

I did Wayne Campbell in this Second City show. He was unabashedly from Scarborough, and I felt that Toronto audiences knew it was authentic to my home borough. John Hemphill had written a song for the show called “Fade Away.” It was set to the tune of “Sail Away” by Randy Newman, and it ended the show. The message of “Fade Away” was that Canada was losing its culture, that our culture was being subsumed by American consumerism. It listed all the things that Canadians no longer paid attention to because of the magnetic power of American consumer culture. An American friend of mine came up to see the show and was shocked at how anti-American the song was.

I said, “Didn’t you think that we Canadians might have an opinion on you Americans?”

“Not really,” he said.

“Well, what do Americans think of Canada?” I asked.

“We don’t.”

Game, set, and match.

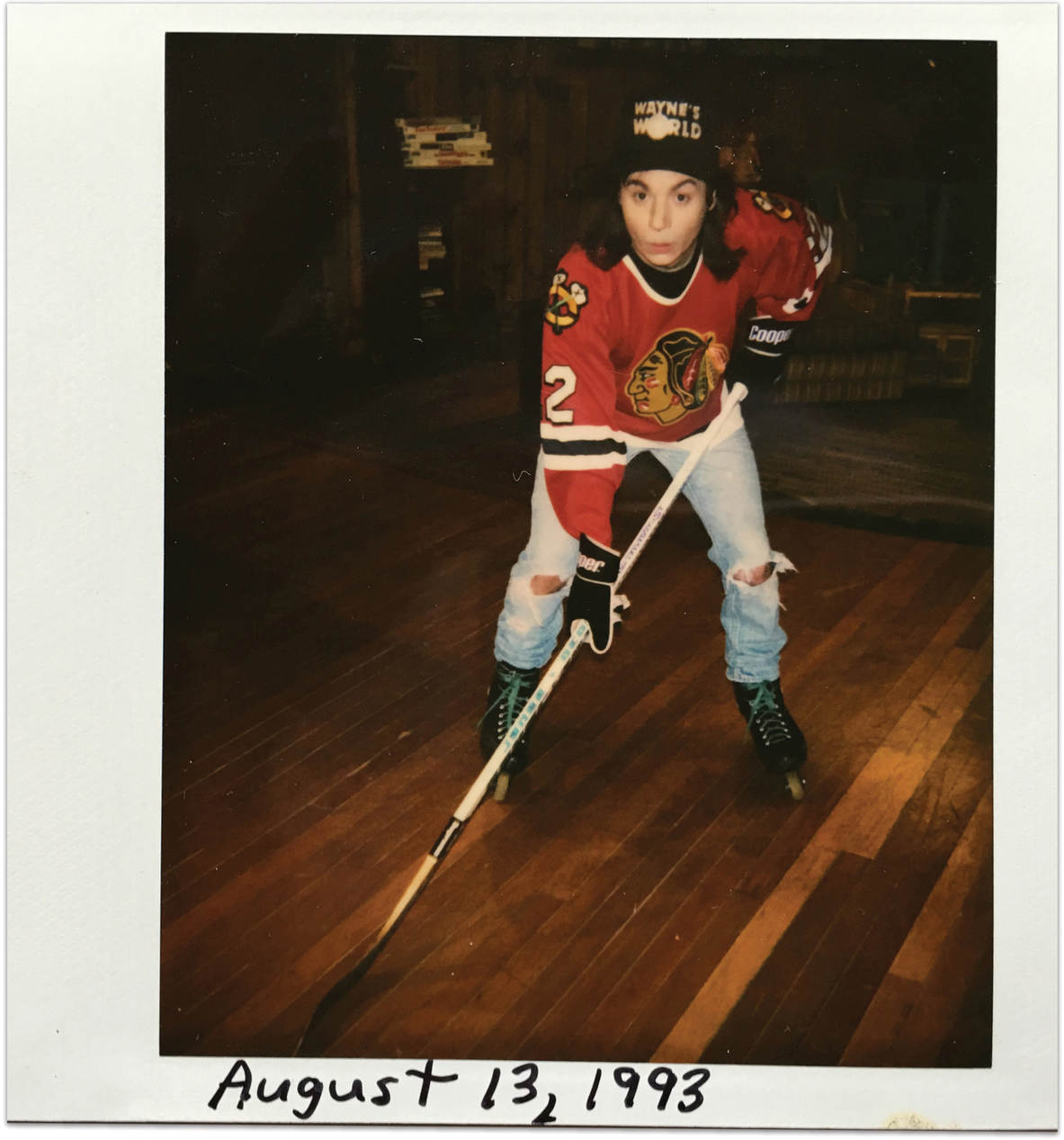

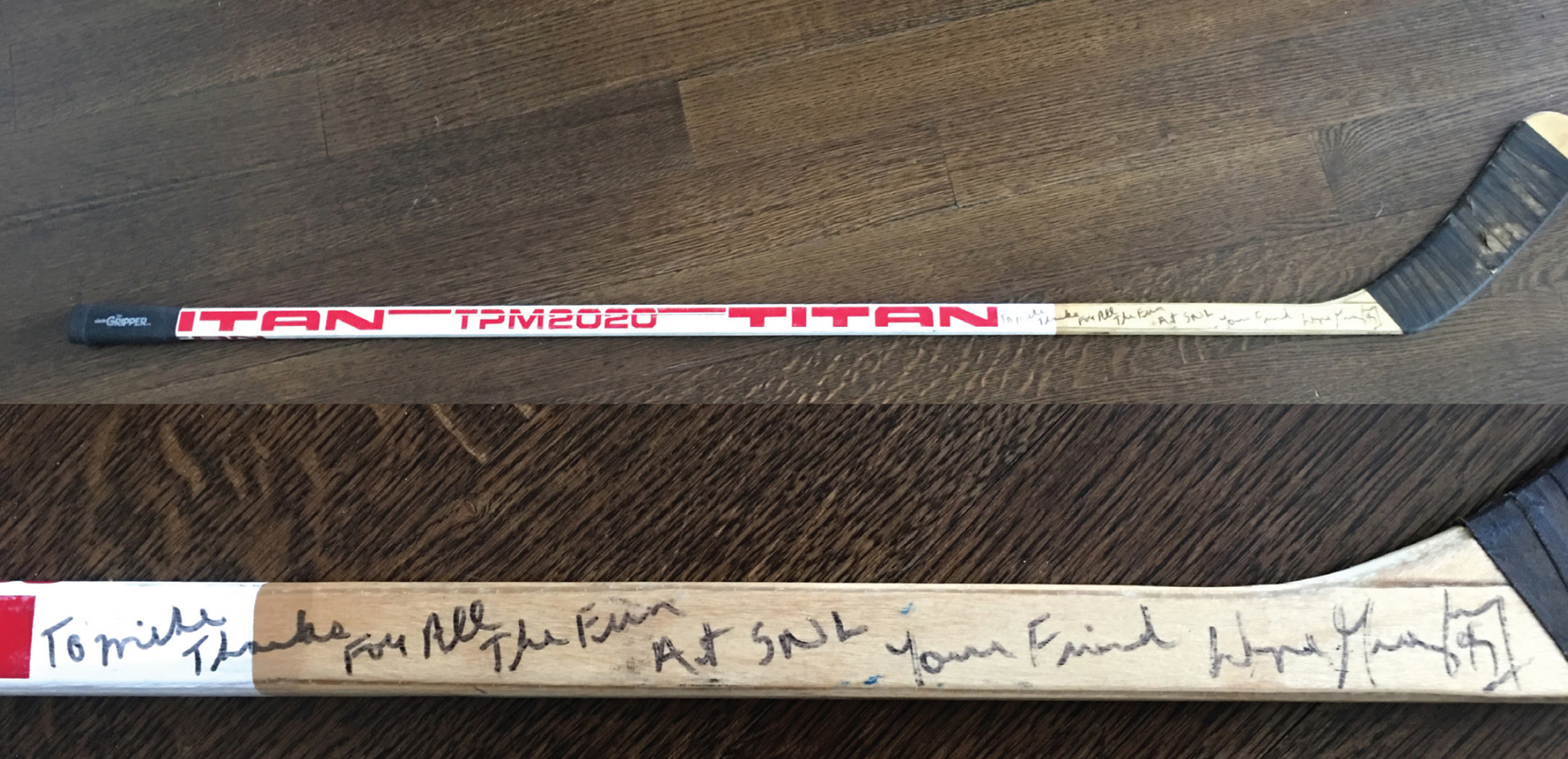

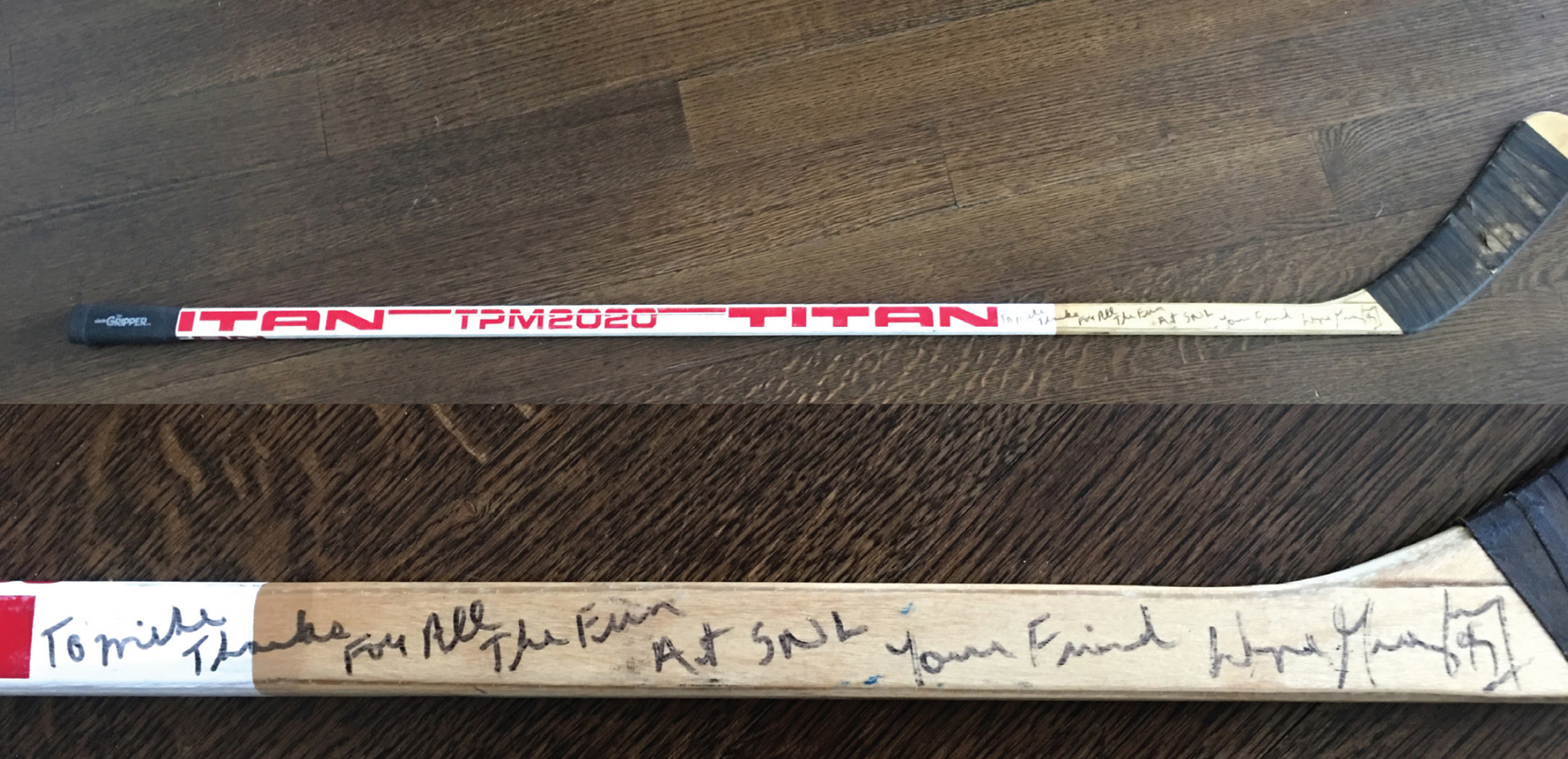

Producers from the CBC saw me at Second City and invited me to do sketch pieces on their show It’s Only Rock & Roll, a rock-themed variety show—sort of a talk show, sort of a news show. I did two characters on It’s Only Rock & Roll: once again, Wayne Campbell, which I did as “Wayne’s Power Minute” out of a panel van we called “The Shaggin’ Wagon”; and a German experimental artist character named Dieter. The producers were pleased, and I was asked to do more and more “Wayne’s Power Minute” segments, leading up to hosting the It’s Only Rock & Roll Christmas special.

My dad’s condition, however, was continuing to deteriorate. There was a brief period when my dad was aware that he had this disease. And in the spirit of “How fast can we find this funny?” he insisted on calling it “old-timers” disease. It was the best of times and it was the worst of times. His condition worsened to the point where he no longer recognized me. The Rubicon had been crossed.

I needed to get out of town. I had never been to Chicago before, but I had a vacation coming, so I went to Chicago to see the Toronto Maple Leafs play the Blackhawks at the old Chicago Stadium. One of the Original Six. I wanted to get to the stadium before it was torn down.

Chicago and Toronto have a lot in common. Toronto is an Iroquois word meaning “meeting place.” Chicago comes from the Algonquian, meaning “wild garlic” or “wild onion.” The cities are roughly the same size. Both are on a Great Lake. Both have a proud tradition of comedy and, by way of our Chicago brothers, improv comedy. But that may be where the similarities end. In Toronto, the subway would take you to College station, half a block from Maple Leaf Gardens, right next to Toronto’s fantastic gay neighbourhood on Church Street. On the other hand, the Blackhawks play in a bad neighbourhood—on the other side of the infamous Cabrini-Green Homes, the housing projects made famous in the 1970s sitcom Good Times. I got in a cab and told the driver I was going to Chicago Stadium. He asked me, in his thick Chicago accent, “Ohh mye Gad. Are you shurr? Dat’s a pritty skeery plase.” This did not bode well. We made our way west, and as we got closer to Cabrini-Green, the cab driver auto-locked the doors, rolled up the windows, and reclined his seat back so far that he was lying down while driving. He sped up to 60 miles per hour and went through a red light! Being Canadian, I didn’t want to criticize him, but when he went through a second red light, I spoke up.

I love the Chicago Blackhawks jersey. It’s a classic. No wonder every Blackhawks fan owns at least one ’Hawks jersey.

“What are you doing?” I asked.

“Snye-purs,” he said.

“What? Snipers? What do you mean?”

“See deez buildings? Dey love to snype cabs. Don’t wurry about da red lights in dis neighburhood. Dey’re just street decoration. If I were you, buddee, I’d get yur head down.”

I lay flat on the back seat, and within five minutes I was at the front doors of Chicago Stadium. The building looked exactly like a doppelganger of Maple Leaf Gardens.

The atmosphere was electric. All the fans wore Blackhawks sweaters. I had been warned not to wear my Leafs sweater, but I had to wear it. I was also told not to celebrate if the Leafs scored. Although it almost killed me, caution ruled the day, and I sat on my hands as Wendel Clark potted a wrister from the left side, top shelf, where mama keeps the peanut butter. To my surprise, Blackhawks fans were polite, welcoming, and downright friendly. We Leafs fans pride ourselves on our hockey smarts, but these Blackhawks fans had the knowledge, despite only getting half a page of hockey news in the Tribune, as opposed to four pages in the Toronto Star. In fact, Toronto has eight pages of hockey news on Tuesdays and Thursdays (heaven). Seeing how hard it was to get to Chicago Stadium, I came away feeling that these ’Hawks fans were true hockey fans. Much respect.

The only grief I got was from a three-hundred-pound Blackhawks superfan who wore every possible piece of Blackhawks merchandise. He was a known regular, shouting out a play-by-play of events on and off the ice in a deep, raspy frog voice with a very thick Chicago accent. As I walked up the aisle, he saw my Leafs sweater and bellowed, “Leafs suck!” When a pretty girl went by, he shouted out, in his frog voice, “Hockey bitch! Hockey bitch!” It was more ridiculous than offensive. The entire section broke into uproarious laughter, including the pretty girl.

It was a far cry from Maple Leaf Gardens, where you could often hear a pin drop. There was an energy in Chicago that, at that time, was lacking in Toronto. I wanted to sample this energy. I wanted to be in the home of the original Second City, where Elaine May, Mike Nichols, John Belushi, and Bill Murray created one of the most dynamic movements of sketch comedy in the history of mankind. It was also the home of Mr. Del Close. Del Close was one of the founding members of Second City back in the 1950s, along with Nichols, May, and Paul Sills. He was older, an ex-junkie, his body covered in track marks, which he called his “track suit.” He was a Wicca witch who often asked his students to invoke demons as part of their improv training. Del was one of the Merry Pranksters, a group of experimental artists and hippies who lived in a bus and were based out of San Francisco. Tom Wolfe wrote about the Merry Pranksters in his book The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. Del was one of the inventors of the Happening, which was an unscripted “event” that ravers would well recognize. He and his partner, Charna Halpern, ran a Chicago theatre called the Improv Olympics. Del didn’t just teach improv, he taught creativity. He would have salons at his house, where the nature of creativity was discussed, and creative “happenings” spontaneously manifested. One day, I brought over a deck of hockey cards, and with these cards I read Del’s fortune, which I called Canadian Tarot.

HE WAS A WICCA WITCH WHO OFTEN ASKED HIS STUDENTS TO INVOKE DEMONS AS PART OF THEIR IMPROV TRAINING.

Improvising my best spiritualist voice, I said, “As there are four divisions in the NHL, there are four energy quadrants that predict your future. I want you to pull out a card. This will be your defenceman card.” He pulled out Ray Bourque. I said, “Ahh, the Ray Bourque card. And I see you’ve placed it in the Norris Division quadrant. There are many fights in the Norris Division. We call it the Chuck Norris Division. Just as Ray Bourque is a stay-at-home defenceman, you will find yourself doing projects around the house. But be careful: his slapshot is hard. Someone you know will turn on you. Don’t be a hero. Don’t try and block the shot.”

Del Close. The man, the legend. The patron saint of improv.

He was a heavy smoker, and my reading of him caused him to laugh to the point of a coughing fit. Gaining his respect was one of the highlights of my creative life. For Del, every art form and all parts of living were to be studied and incorporated into improv. One day, Del was giving a workshop. He was talking about how important it is that the performer not believe that they were better than their audience. He felt the audience was always smarter than the person onstage. He told a story of going to the Canadian National Exhibition and finding himself in one of the trade show buildings. He was looking at the mass of people going from booth to booth, like so much human cattle. He had caught himself feeling superior, but then he passed an Encyclopaedia Britannica booth where a Liverpudlian man was selling encyclopedias. He said that this Englishman was so funny that it reminded him that a sense of humour is not exclusive to professionals. I raised my hand.

He said, “Can I help you?”

I said, “Yeah. That Liverpudlian selling encyclopedias?”

“Yeah?”

“He’s my father.”

The rest of the class gave a collective gasp.

I’m serious. This actually happened. Spooooky.

But things like this were everyday occurrences in Del’s class. There was an element of magic. Ideas flew around the room, connections were made, synchronicity was rife. Del’s classes had an almost hive-mind quality. And it was intoxicating. And it wasn’t Toronto, where my dad was. Or wasn’t.

So I applied for a transfer from Toronto Second City to Chicago Second City. The owner of Second City Toronto, Andrew Alexander, and his Chicago counterpart, Bernie Sahlins, were kind enough to grant that request. My entry into Chicago Second City mainstage was not an easy one. There was much resistance. One Chicago cast member took me to lunch to “be my friend” by informing me that I was not welcome in Chicago; that the cast, whom I had only briefly met, resented my foreign intrusion; and that my Toronto Second City style of improv and comedy, which emphasized character and observation, didn’t jive with the superior political satire tradition of the “senior” Chicago mainstage. I wasn’t used to this type of psych-out aggressive behaviour. Comedy in Canada and Britain is not a macho affair. Canadian comedy is much more self-deprecating. I had heard stories of Bill Murray diving into the crowd of Second City in Chicago and having fist fights with hecklers. We didn’t do that in Toronto.

On my third week at Second City Chicago, it was a particularly cold day and we were rehearsing in the empty, freezing theatre. I had only one sweater, which my beloved Aunty Molly had knitted for me. I wore it so much that it had a hole in it. At one point in the rehearsal, one huge Chicago castmate interrupted me and said, “Nice sweater…Why don’t we all pitch in and get Myers a new sweater?”

I said, “Why don’t we all pitch in and get this fucking asshole some manners?” There was an uneasy, hushed oooooh from the rest of the cast. I don’t know where my quick response came from—probably Scarborough. In Scarborough, you have to be fast, you have to be funny, or you have to be ready to fight. I was transported back to the Toronto subway platform at Kennedy station—the end of the line.

Later that night, I was onstage, improvising a scene about world affairs. I played a stuffy British diplomat, who made three—I thought reasonable, and not terribly controversial—statements. In my Brit character, I said, “The Kennedys were rum runners to Canada,” “Canada won the War of 1812,” and “The Americans dropped the atomic bomb on the Japanese, not to bring Hirohito to heel, but to scare the crap out of the Russians as an opening salvo of the Cold War.” Some members of the audience took mock offence at these remarks, but overall my British character was well received, getting some nice laughs.

When I got backstage, that same huge Chicago cast member pinned me against the wall, screaming, “How dare you come to this country, take an American job, and take a shit on America?” I was shocked. Wasn’t Second City a bastion of Democratic politics? Wasn’t this the theatre that the rioters from the 1968 Democratic National Convention ran to as sanctuary from Mayor Daley’s “pigs”? This dude was huge. And I was cornered. I realized that I was in a physical fight, and once again Scarborough came to the rescue.

In my thickest Canadian accent, I said to him, “Hey, buddy, get your fucking hands off me! Or there’s gonna be two sounds: my Canadian fist breaking your ugly American jaw, and your Yankee head hitting the fucking floor.”

“Oh yeah, jagbag?”

I said, “Jagbag? What the fuck is a jagbag? You Chicago pricks can’t even swear right! I’m Canadian, asshole. I’ve been in thousands of hockey fights. I don’t give a fuck how big you are, I’m gonna fuck you up hockey-style.” For the record, I’d never been in a hockey fight. But it worked. He let me go. He would’ve killed me. In my head, I thought, Did I almost get in a brawl? We’re doing comedy, people. I hate fighting, but my Liverpool dad had always said, “You only fight to get out of a fight,” and he was right. It was a Scarborough bluff.

Despite a couple of dust-ups, I do love Chicago, and the people I worked with were very talented, very passionate, and very dedicated artists. The late Bernie Sahlins and the late Joyce Sloane were lovers of the arts, and generous believers in me. I am honoured to have had the privilege of walking that storied stage. Del Close was a creative genius, and amongst his talents was the gift of exploring and heightening the talents of others. He was a true revolutionary in the “Actors Liberation Movement,” which is what Del liked to call improvisation. Above all, he was brave enough to insist on truth, even at the expense of a joke and even at his own expense.

He was a kingmaker, having honed the likes of Belushi and Farley, but he was so committed to the truth that he once bravely said of himself, “I am the door through which others pass, and I cannot.” While he enjoyed comedy that came from a place of “wouldn’t it be funny if…,” he treasured comedy of truth, comedy that started from, “isn’t it funny that…” I owe much to Chicago, but I wasn’t meant to stay there long.

Meanwhile, at that time, Toronto Second City was celebrating its fifteenth anniversary, and because I had moved to Chicago, I was now technically an alumnus, thus eligible to participate in Toronto’s star-studded fifteenth anniversary alumni show. Other alumni included Martin Short, Eugene Levy, Catherine O’Hara, Andrea Martin, Joe Flaherty, and Dave Thomas. In the crowd were many celebrities, like Michael Keaton, as well as producers and casting directors. It was a big deal. I flew back to Toronto and had the novel experience of staying in a hotel in my home city. When I got to the theatre, it was packed with television crews and fans waiting outside to see who was arriving. I, of course, took the subway there and entered through the back door because I was not somebody anyone wanted to see.

I WAS IN VERY FEW SKETCHES COMPARED TO THE STAR CAST MEMBERS. I WAS HAVING FEELINGS OF NOT BELONGING.

I went backstage, looked at the running order, and saw that I was in four sketches. Very few sketches compared to the star cast members. I was having feelings of not belonging. I got why the big stars were there, but I was unknown. During the first act, I did two of my four sketches. The first played to polite applause; the second was plagued with so much audience chatter that Michael Keaton generously began a shushing campaign. At the intermission, I went downstairs. I was despondent.

Dave Foley, from the Kids in the Hall, caught me downtrodden. He said, “What’s going on? You’re killing out there.”

I said, “I feel like such an asshole. I shouldn’t have come. The audience just wants to see the stars, and I don’t blame them. I’m thinking of going home.”

Then Foley said, “What do you have in the second act?”

I said, “I start the second act with Wayne Campbell.”

He goes, “They’re letting you do Wayne?! You’re gonna kill, asshole. It’s gonna be great.” It was the bucking up that I needed. Foley has always been my champion.

Dave Foley. A Canadian genius.

I changed into my Wayne costume and took my starting position, which happened to be in the crowd, breaking the fourth wall. The lights came up, drunken stragglers took their seats, and I began performing from the crowd. At first, people thought I was an underage heckler. Then, people started to get it. Then I got my first laugh. Then I took the stage. And then it started to grow. “B” laughs. Then “A” laughs. Then laughs where we had to hold, waiting for the audience to finish. Then everything played. And when the lights went out, there was thunderous applause, cheers, stomps, whistles. It was like a jet taking off. It had fucking killed. I was stunned.

There was an after-party upstairs, in the dining room above the theatre. As I took my place in the line, I heard a voice from below. It was Michael Keaton.

“Hey, kid.” He ran up two flights of stairs. “That Wayne sketch is awesome. Congratulations!” I couldn’t believe his generosity. My fellow linemates were just as blown away.

“That was Michael Keaton, you know.”

“Oh, I know,” I said.

At the after-party, there was a main table where all the big names, including the SCTV cast, sat and schmoozed. I took a table way in the corner, as far away from the main table as possible. The SCTV cast were and are my heroes, and I didn’t want to crowd them, like others were doing. They came over and sat at my table. I couldn’t believe it. They were so incredibly generous and nice. It was a magical evening.

The next day, I returned to Chicago and got a phone call. It was Lorne Michaels.

He offered me a job as a featured performer and writer on Saturday Night Live.

Martin Short had recommended me to Lorne, based on my performance at Toronto Second City’s fifteenth anniversary show the night before. Another Canadian, Pam Thomas, producer on The Kids in the Hall and wife of Dave Thomas, who had also been there that night, also called Lorne on my behalf. Yet another Canadian, my dear friend Dave Foley, had called Lorne Michaels. I felt like I was being taken care of by the Canadian mob. I thank them all.

Many things coalesced on that day. I remembered that I had promised myself I would never go to New York unless I was offered a job. I flashed on the first time I saw Saturday Night Live, with Gilda Radner, when I, Sucky Baby, had precociously declared that I would someday be on that show. And I was also reminded that the person I most wanted to see me on Saturday Night Live, my dad, would never know.

When I got to New York City, it was a whole new world. Although Toronto is only five hundred miles away, it might as well have been in Alpha Centauri.

As a fellow Canadian, Lorne Michaels knew my particular challenges. He said I had a good chance of doing well at SNL because I would have the Canadian humility that says, “I’d better work hard and study.” But he also cautioned that, as a Canadian, I would have a hard time accepting that talent and character don’t always go hand in hand. He said that, as a Canadian, I would be devastated when one of my heroes turned out to be a prick. And of course, he was right. Over time, I came to accept the talent–character discrepancy. But it’s true.

Canadians will ask, “Have you met so-and-so?” and if I say yes, their follow-up question is, “Was so-and-so nice?”

Americans will ask, “Have you met so-and-so?” but their follow-up question is, “What’s so-and-so like?”

Canadians need to know they were nice. Americans just want the inside scoop. If they’re nice, fine. If not, oh well.

In many ways, because I was a fellow Canadian, Lorne took me under his wing. Lorne is very erudite, with a wide knowledge of history and art and an appreciation of European films. I too loved European films, and because Toronto is such a movie town, I was familiar with many of the films he spoke about. I shared with Lorne my love of the French film director Louis Malle. To my delight, Lorne told me that not only was he friends with Louis Malle, but that in a few weeks he would be coming to New York because his wife, Candice Bergen, was going to be hosting SNL.

Lorne Michaels and me in 2014. We are backstage at SNL, moments before I guest-performed Dr. Evil in a sketch about the controversial Seth Rogen movie, The Interview. Seth Rogen is from Vancouver.

Louis Malle. To my delight, Lorne invited me to dinner with the great director.

Lorne invited me to dinner with Malle. It was to be My Dinner with Louis. For the entire meal, I sat silent, intimidated by my boss and in awe of Monsieur Malle. Lorne told Louis that I had written a high school essay about his movie Lacombe, Lucien. The essay was called “Lucien Lacombe: Evil Villain or a Product of His Time?” Lorne, in an act of incredible generosity, said, “Mike, I believe you have a question for Louis.”

I said, through a croaking voice, “Monsieur Malle, I wrote an essay about Lacombe, Lucien, in which I wondered if the main character, Lucien Lacombe, was evil or just a product of his time.”

He said to me, “What conclusion did you draw?”

I said, “I thought he was a product of his time.”

Louis Malle said, “Oh no, he was just evil.” When does that ever happen in life? I felt like Woody Allen in Annie Hall being able to pull Marshall McLuhan from around the corner. People always say that you never use the knowledge you learned in high school. I beg to differ. Thank you, Canadian education system. And thank you, Lorne.

Lorne and I bonded over Canada. He was amused by my constant Canadian obsession with fairness—this wasn’t fair, that wasn’t fair. One day, somebody had done something to me that was absolutely, without question, so completely unfair. I was really upset, and, honestly, rightly so. In Scarborough, nobody likes a snitch, but this was so bad that I had to go and tell the boss. I waited an hour outside of Lorne’s office, getting angrier and angrier at how unfair this person had been to me. By the time I got into his office, I was steaming.

IN SCARBOROUGH, NOBODY LIKES A SNITCH, BUT THIS WAS SO BAD THAT I HAD TO GO AND TELL THE BOSS.

I said, “Fuck me, Lorne. Blank blank did blank blank. That’s so unfair.”

Lorne said, “Yeah, you’re right. But, Mike, you don’t want the world to be fair.”

I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. Had so many years in New York erased every molecule of Lorne’s Canadianness? I said, “What?! Of course we want the world to be fair.”

Lorne said, “No, Mike. You don’t want the world to be fair. For example, it’s not fair that you’re more talented than most people.”

I was dumbstruck. What a brilliant way to get someone to get off the whole “fair” thing. Flattery! Genius! I don’t know if Lorne actually believed the things he said about me, but I can tell you it stopped me cold. I could have slept for ten hours. I back-pocketed the “You don’t want the world to be fair” move and have used it successfully with my children.

Lorne reminded me that I wasn’t in Canada anymore. Here in America, people play for all the marbles. Americans pitied their athletes who only got a silver, feeling badly that the silver medallist had “lost.” He said that the civility I had grown up with in Canadian show business was due to the fact that there was no money in it. It’s very easy to be civil when the stakes are low. In America, the rewards were great, but so was the competition. And so was the pressure.

Working on Saturday Night Live is so all-pervasive that it’s like working on a submarine under the polar ice cap. You write Monday and Tuesday, read the material Wednesday, rehearse Thursday, Friday, and during the day on Saturday, you do a dress rehearsal that isn’t shown to the public, and then the actual show that airs live at 11:30 p.m., ending at 1 a.m. There’s an obligatory party in Manhattan, and you get Sunday to nurse the hangover. And then it starts over again. The contract is for six years. Dana Carvey described being on the show as “once a week being shot out of a cannon with no net to catch you.” Gilda Radner described Saturday Night Live as “an underrehearsed Broadway opening once a week.” She also said that “it’s an insatiable monster that eats your material, insatiably.” Lorne described the show as “the court of the Borgias, and even the nicest Borgia still has a poison ring.”

On one occasion, a crew member gave me a cappuccino. Lorne took it out of my hands and said, “Do you know him?”

I said, “No.”

“Never take a drink from someone you don’t know.” And he threw the coffee in the garbage.

And then, on my fourth show, I saw what he meant. I had been hired halfway through the season. I wasn’t a full cast member, so I had to write for myself. I’d had some small pieces in sketches, but nothing I’d written had gotten into the show. As I mentioned before, Wednesday is read-through day. At read-through, the cast sits around a table with the host and Lorne, senior producers, and the director. Chairs are brought in that are arranged around the read-through table, forming a gallery. The writers all sat together on the right, production staff on the left, and the technical artisans in the centre. To call the read-through a tough room is like saying Ebola is a bad cold. The writers don’t want you to succeed, the producers are afraid that the show’s going to be too complicated to produce this week, and if you’re a new guy, like I was, the technical staff don’t know who you are and aren’t sure you’re going to be around next week. As for Lorne, the man has literally either heard, or written himself, every possible joke combination known to mankind.

It was Tuesday night. I had decided it was time to do my Wayne Campbell character on SNL. If it flamed out, I lost my big gun. I had struggled with how to introduce the character for the three previous shows, but I had hit on an idea of placing Wayne in a cable access show, as cable access was hitting its stride. I would make it the most local show in the history of television. It would literally be about Wayne’s basement and, if he was feeling adventurous, upstairs. I struggled with having Wayne be a Canadian. I’d been in the States long enough to know that there was a universal, suburban, heavy metal kid experience: the same long hair with baseball cap, workie boots, ripped jeans, black concert T-shirts, and the belief that Zep was God. And all heavy metal guys wanted to do was look for chicks.

And besides, within a week, I realized that none of my American coworkers, writers, or actors knew anything about Canada. Most thought that Montreal was the capital city, not Ottawa. The majority didn’t realize that we had our own currency. They all thought that Canada only had winter. Some were confused that I was claiming to be Canadian, and yet I was only five-foot-seven, as if it was the land of giants.

So I started to play games.

I insisted that Canadian Tire money was our actual currency, a claim that went unchallenged. I told them that not only was there a Canadian Thanksgiving, but that there was a Canadian Christmas—in July, when Jesus actually died. That July, one sensitive American colleague sent me a Christmas card. I became a one-man public relations firm for Canada. I began to pretend that I wasn’t familiar with universally known American customs. For example, I feigned ignorance of Independence Day, sarcastically asking if it was “America’s equivalent of Canada Day.” I pretended to not know the name of the World Series, coyly calling it the “Stanley Cup of baseball.” Not only was I out of the country, but I was starting to go out of my mind. In retaliation, Kevin Nealon developed a “Mike Myers” impression that started every sentence with “In Canada…,” with the same singsong of the girl in American Pie who started every sentence with “This one time, at band camp…”

I decided that Wayne would be from Aurora, Illinois, just outside of Chicago, because there is a town called Aurora, Ontario, just north of Toronto. Aurora, Ontario, is very similar to Scarborough. I made no concession to a Chicago accent. I wrote Wayne’s first SNL sketch on a yellow legal pad, handwritten and stapled. I called the sketch “Wayne’s World.”

At five o’clock on Wednesday morning, I put the sketch on the hand-in pile outside the head writer’s office. It was an intimidating pile, usually consisting of forty or so sketches. The cast and writers I had been hired into were of the highest quality. I thought they were going to be good; I didn’t know they were going to be that good. I took a seat on one of the couches and started to drift off when one of the senior writers came into the read-through room, went over to the pile, and picked up my sketch. In my head, I was screaming, You can’t look at the pile! But he was doing it. As he read my sketch, not only was he not laughing, but he was shaking his head in disgust. He caught me watching him.

He said to me, “Did you write this?”

Holding back both tears and vomit, I said, “Yes.”

And with that, he took my sketch off the pile and put it on the read-through table!

My mind started racing. What does that mean? Does it mean he just decided I wasn’t allowed to hand it in? I didn’t even know you were allowed to look at the pile. Wait a minute, he just took my sketch off the pile and put it on the read-through table.

Then he left the room. I froze. A second later, another senior writer came in and picked up my sketch off the table and began to read it. His reaction was a little more animated. As he read, he said things like “No!” and “Oh my God, this sucks,” and then “Seriously?”

He turned to me and said, “Don’t hand this in. It sucks. You’ll never win over the read-through table. Honestly, this sucks.” Then he took my sketch and threw it on the ground. HE TOOK MY SKETCH AND THREW IT ON THE GROUND. It was five o’clock in the morning. I was jet-lagged. I was vomitous. I wasn’t even angry, I was freaked out. I’d finally made it to Saturday Night Live, I had a character that people seemed to like in Canada, I thought I finally found a way to get it on the show, I’d worked my ass off combing through it over and over again, I’d gotten up the courage to put it on the dreaded pile, and now my career was over. I sat down for twenty minutes, staring into space, wondering what I was going to tell my friends in Toronto. I was trying to come up with what I call my “dignity answer,” the story I would tell them about why I had been fired, while somehow making it seem it wasn’t my fault and it was the best thing that had ever happened to me.

NOW MY CAREER WAS OVER. I SAT DOWN FOR TWENTY MINUTES, STARING INTO SPACE, WONDERING WHAT I WAS GOING TO TELL MY FRIENDS IN TORONTO.

And then something happened.

As if a hand had pulled me up by the scruff of my neck, I got up, went over to the sketch, restapled it, and put it back on the pile. I thought, Fuck it. I’m not gonna let these assholes psych me out. If it dies at the read-through table, fair enough. But I’m going down swinging.

A calmness came over me and I walked home through the empty, freezing canyons of Midtown to my four-hundred-square-foot apartment and slept. When I woke up at 1 p.m., I zipped in a cab to 30 Rock to see if my sketch had indeed been typed up and put into the read-through pack. It had, but it was sketch number 40 of forty sketches.

In order to soothe the host, the producers would front-load the read-through with sketches they thought were likely to get in. Best came first, worst came last. At around sketch number 20 in the running order, everyone starts to get antsy. They know that the crappy sketches are coming, everyone is sleep-deprived, and everyone starts to get hungry. Lorne starts to eat his carrots around now, which is tough because he reads the stage directions, so now, if your sketch is in the second half of the pack, the stage directions are read with a full mouth. Lorne himself sometimes would start to make comments about the quality of the second-half sketches, saying things like, “Honest to fuck, can’t we screen some of this bullshit?” My sketch was last. The crowd’s patience was running out.

Finally, it came to my sketch.

Lorne turned to everyone and said, “How are we all feeling? Should we do this?”