Geometry of Taste

Ever since Lalji Hemraj Haridas appeared on the scene, it had become apparent that this was a man who knew how to make bioscopes work. From the day he took over the Alochhaya Bioscope Company—the ‘Theatre’ in the name was dropped swiftly—not only did many more people start entering the theatre to watch fifteen to forty-five minutes of sheer motion pictures, but the quality of the fare, too, drastically improved.

But it was only in late 1918 that Lalji displayed his true genius. This man, who had just a few years ago struck us as being a coarse, jewellery-obsessed Marwari, called a few of us into his office—the same room in which Mahesh Bhowmick had once counted notes and coins—and showed us a diagram.

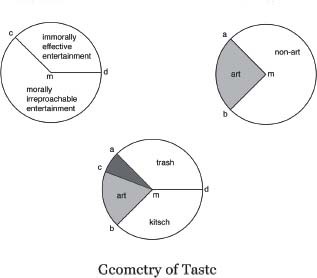

‘This, my friends, will be our business strategy, our philosophy for bioscope-making and bioscope-showing from now on.’ And he unrolled the rolled-up paper, and this is what we saw:

In that room, now brighter because of the new electric light as well as a mammoth gold-plated statue of a reclining Ganesh, we all looked at the ‘Geometry of Taste’. I bent my head to get a better view and waited for the lecture. Lalji beamed and slid forward in his chair, ready to explain.

‘As you can see, there is an overlap of the kind of motion pictures that can be considered artful and non-artful and motion pictures that affect audiences morally and immorally. I am a family man, gentlemen, and I want us to make bioscopes that I can show my children and family. If a man goes alone to watch a bioscope, that’s one ticket. If a man is comfortable enough going to a bioscope with his family, that’s at least five tickets sold at the counter. But at the same time,’ he said as he granted us a heavy smile that seemed to drag his jowls down, ‘I want people, all kinds of people—the degenerate, the loafer class included—to come and watch our bioscopes. And people don’t want to be just instructed or lectured to any more. Those days of audiences coming saucer-eyed to see photographs moving are over.’

That was true. The theatres that still insisted on showing some of those imported ‘Adventures’, ‘Wonders of the World’ and ‘Brave Explorations’ were losing money. Just pointing the camera at strange, unknown places and people no longer did the trick. As for the old hit shorts, such as Hiralal Sen’s Anti-Partition Demonstrations and Swadeshi Movement at the Town Hall on the 22nd September 1905, which were still being shown in some halls trying to cash in on the Swadeshi fever, people were simply finding documentary pictures dreary. After all, how much can you get excited, some thirteen years after the event and more than a decade after a camera had stopped pointing at horses wagging their tails in a line, or dullards opening and twitching their mouths in front of a large congregation? Where was the action? Where was the story? As Horen Ray had once said, ‘What will the orchestra play along with that?’

‘Straight morally uplifting stories are nice. But they leave the crowds fidgeting and forgetting what they saw the moment they stand up to move towards the theatre exit. We need bioscopes that aren’t part of their everyday, ordinary, bone-crushingly dreary lives, things that are impossible for real lives to experience. Partho-babu, what is the scene you remember the most in The Sixth Pandav?’

Partho Basak had joined Alochhaya some years earlier as art director and, although he was a tame fellow who kept to himself and his pile of books on theatre set production that he had brought back with him from Germany, over the years he had become a key player of the Alochhaya Bioscope Co.

‘Well, Lalji … the scene in which Karna’s chariot wheel is stuck in the mud and he looks at, er, Arjun approaching …’

‘Rubbish, Partho-babu! You and your European notions of crooked angles and headache-inducing backgrounds! We all remember the scene in which Draupadi is being disrobed by the Kauravs. You know that, I know that. And it’s safe. No authority will have a problem with it. And no audience will get scandalized by Tara Bibi being peeled and standing as a white blur in front of them. And you know why? I’ll tell you why. Because that scene is already in the country’s most popular story. And it’s so popular that a child is regularly retold the bit without anyone breaking into rashes. It’s that disrobing bit that thousands will remember. And it’s not like the stage where no matter how realistic the actors are, no matter how realistic the sets are, the audience will be aware that it’s not the real thing. Gentlemen, the beauty of the bioscope is that it seems real. It can actually be more real than the real thing!’

Lalji went on to unveil a startlingly simple plan. Carrying out this plan would make the public take to Alochhaya bioscopes the way a sinner takes to penitence. We would produce bioscopes, he explained, keeping the thin blue wedge in the ‘Geometry of Taste’ diagram—the slice that is ‘amc’ in that third circle—as our area of operation. In other words, Alochhaya bioscopes would be immorally effective entertainment that was artful at the same time.

‘I have no problem with that. But what about the family crowd? You just mentioned that you want respectable people to bring their families to bioscopes too,’ said Shombhu-mama, whose unscheduled departure from the city was still some months away.

‘Ah, that’s where we come to the second and more important aspect of bioscope-making.’

Lalji Hemraj, for all his cold business acumen, was working himself up. It was usually difficult—on account of his perpetual smile—to guess at his emotions by peering into his face. But there was an easy way in which to find out when he was truly excited about something, and that was when he began to speak Bengali, the language being drawn out of him as if by a pair of invisible horses tugging on opposite sides of individual words. The Marwari in him would then take over. As it did now:

‘I’ve called it the Theory of Compensating Values. If virtue is always rewarded and sin is always punished, if good always triumphs over evil, and if the bad man is always punished miserably at the end of the bioscope, everyone’s satisfied—the authorities, the family, the individuals. So we can show sin—and we’ll have to. But all we need to ensure is that all sinners come to a bad end. Vice will be the main theme of most of our features, but in every one of them virtue will triumph. Draupadi will be shown being molested by Dushyashan but Dushyashan will then be shown to have come to a very sorry end. You know what I mean, don’t you, Abani-babu?’

I nodded my head furiously. I understood what he was saying. I understood it perfectly because I knew what he was saying even before he had said it. I hadn’t the words for it only because the bioscope was—I don’t hesitate to say this—in my bones.

Lalji leaned to a side as if he was going to break wind but, instead, picked up a sheaf of papers from behind the table.

‘Look at this.’ And he read out in his limping English from an American newspaper that didn’t look too dated with creases.

‘Here’s what the Daily Bugle of Chicago has written about a hit that’s packing picture palaces across America. It’s called The Inside of the White Slave Traffic. Let me just read out a line. He’s the president of the American Sociological Fund, Frederick H. Robinson,’ saying which Lalji peered into the paper and read as steadily as his paan-munching mouth would allow formal English to be spoken in.

‘“We are glad to give The Inside of the White Slave Traffic our unqualified endorsement.” And wait, there’s another quote from the Medical Review of Reviews: “I consider this film to be a truthful presentation of a particularly vicious phase of life—a correct portrayal of those horrible occurrences which cannot but arouse a tremendous public sentiment.”’ Lalji looked up from the paper, shone out a smile that would have exposed any film in the darkest of rooms, and victoriously repeated the words ‘tremendous public sentiment’, thereby dousing them with a special, tingling significance.

This done, he banged on the bell on his table. He wanted some water. It was obvious that he knew that he was on to something novel and yet something that was also the most obvious thing in the world. But even at that point not one of us was clear about how we would put his excellent theory into practice. Would the public accept moral depravation if it was displayed on a bioscope screen? Would any one of us be comfortable doing the basic necessary job required in such a scheme of things even in the manipulative world of the bioscope?

I looked at the posters on the wall behind Lalji. There was Prahlad Parameshwar in which I was grasping Durga inside what looked like either a pyre or a thicket. It was clearly a bad sketch. There was another poster of the very successful Anandamath with a slightly more acceptable drawing of a band of sanyasis brandishing swords and the letters making up the title melting into dripping blood.

Lalji continued, ‘Dr Pankhurst says, “Every woman should see this film exposing white slavery and its attendant horrors.” And here’s the line on the showcard: “This is a film with a moral; a film with a lesson; a film with a thrill.” That’s what I call brilliant! That, friends, is what Alochhaya needs.’

In other words, Lalji wanted bioscopes that would make audiences come into picture palaces in hordes, without feeling that there were something awry about them—just as the hordes on the other side of the world were crowding into darkened halls to see The Inside of the White Slave Traffic, a feature about white prostitutes in America. Real success lay in making motion pictures within that thin blue sliver that was the triumph of artistic degeneration—a repertoire that would always be accompanied by the message that sins were worthy of contempt and would always, without fail, lead to an end that was worse than death.

Bioscope-watching would not become going out for a night at Bowbazar, or an evening of music with baijees, or cavorting with the crude entertainment of the English plays with their Anglo actresses. This was bioscope that would make people aware that the world was a wicked place and the only way to protect oneself from the wickedness was to be aware of it. And what could be a safer place to be aware of sin without the fear of committing it than the comfort of a bioscope theatre?

Lalji Hemraj was a genius.

Lalji’s lecture made me more of a bioscope creature than any other single event that I can think of. I understood the true potential of the bioscope—its potential for spectacle, for commerce, for seduction, for honest, nuanced trickery. It felt good to be part of such intelligent mischief, and I became keenly aware of my actions as an actor. Before the beginning of any shooting, my body and I would spend a few weeks not getting along with each other. It wasn’t the outcome of some crafty, clever, thought-out process, like deciding which shirt to wear for maximum impact in what kind of light conditions, or how to position one’s mouth when talking and how when not talking, or indeed what words to speak. It was something more automatic, like buttoning a shirt, or swearing silently when the pretty girl in the tram is lost behind a thicket of bodies.

There is no inherent harm if, for an elongated moment, one actually starts thinking about the process of buttoning one’s shirt or why one is disappointed not to be in the visible presence of beauty. But buttoning the shirt and thrilling to the sight of a pleasing form do become difficult and false. In the case of the shirt, the two opposite actions of buttoning and thinking about buttoning leave one giddy. There are some things in the world that one must pay attention to and others that shouldn’t be attended to at all. Pushing each button into each slit of a shirt front, staring at a stare-worthy woman, acting that one is somebody else can only succeed if one stops thinking about the verbs attached to all three of them.

It was while I was refirming my craft in this manner, which I can now admit was more than a little self-conscious, that we heard of a version of the Black Hole of Calcutta that seemed to us to be good bioscope material. It didn’t take us more than a couple of weeks to track down and get in touch with Bholanath Chandra, a landlord living in a two-room apartment in Shyambazar. The very undistinguished-looking man, scrawny as a crow’s beak and as dark, dry and noisy as the bird, had unofficially proved a few decades ago that the old story about the Black Hole of Calcutta was bunkum, stating that a floor area of 267 square feet could not possibly stash 146 European, overwhelmingly male, adults within its confines.

His reasons for proving that the Black Hole story about native barbarism against European bravery was all nonsense arose not out of any nationalistic motive, but out of a more practical concern. One of his tenants had filed a case against him in the court that the rent he was dishing out entitled him to an adjoining room in addition to the terribly cramped one-room place he shared with five other members of his family. Bholanath kept the other room locked with a heavy padlock, hoping to rent it out to a bachelor in the very near future. It was his refusal to let the room be occupied by his scheming tenant that had led the latter to petition the court. The tenant had remarked in his notified complaint that Bholanath Chandra had refused his perfectly legitimate request because he was planning to make his whole family perish in that crowded, claustrophobic room the same way ‘the Nawab had killed 123 Englishmen by suffocating and crushing them to death in a Fort William guard house in 1756’.

So in his bid to prove that the rent being charged was not the cut-throat amount that his disgruntled tenant was making it out to be—and that even if he wanted the tenant to clear out of the one-room place in his house on Paddopukur Road, he would surely seek bhadralok ways—Bholanath became determined to prove not that his tenant’s floor area was much larger (and therefore worth every anna-paisa of the rent) than the complainant insisted it was, but to prove beyond any reasonable doubt that the ‘Fort William prison cell comparison’ had been ‘wrongly made’. He would prove that the 1756 Black Hole incident was a piece of fiction.

Bholanath fenced an area of 18 feet by 15 feet with hard bamboo and crammed as many of his employees as possible—all Bengalis—into the carefully measured space. He chose a December day for the demonstration as he ‘obviously didn’t want anyone to collapse from heatstroke or fatigue’. The number that could fit into this area was found to be a gnarled, gnashed, limbs-atwist, heads-akimbo 44.

‘And everyone knows that a Bengali’s body occupies much less space than any European’s,’ he famously told the court after he had conducted his experiment twice, the second time in the presence of two court officials. As the never-blinking Crown’s justice would have it, the tenant did win the case against Bholanath, thereby managing to permanently occupy not only the small room in which he and five other members of his family lived, but also two other rooms next to it, one of them being the padlocked room in which Bholanath had been hoping to install a tenant.

But in the process of his futile experiment, Bholanath had become a local legend. Even much later, when the nationalist papers like Jugantar published long, thunderous essays on the lies spread by the English in India, there would be a paragraph on the so-called ‘Black Hole of Calcutta’ and how Sri Bholanath Chandra had ‘scientifically and effectively proved that it was yet another fabrication fuelled by London’s unholy desire to feed its own people on lies and keep its tight leash on the Indian imagination’. Even an English paper in Manchester was supposed to have carried the name of ‘Bolanauth Chunder’ for exposing ‘imperialist attempts to create a mountain out of a non-molehill’.

And it was remembering Bholanath Chandra that my fellow Alochhaya actor Dinesh Boral suggested a feature on the Black Hole, and also that the studio try and get Bholanath’s support in promoting the bioscope. It was decided that a few laudatory words printed on the posters and the publicity pictures before and during the release of the bioscope, The Black Hole of Calcutta, or Survival of the Fittest, would do the trick for the nationalist bioscope viewer.

It had been made clear that Alochhaya couldn’t afford to run foul of the authorities. To show that the Black Hole story—of 146 European prisoners being crammed into a cell measuring 18 feet by 14 feet 10 inches by Shiraj-ud-Daula’s men, and only 23 coming out alive the next morning—was an exaggeration would be inviting official alarm. After all, this was still February 1919, Rowlatt lurking round the corner. Any blatant challenge, through a bioscope story or otherwise, could lead to the confiscation of the print of the motion picture, the arrest of at least Lalji Hemraj and even the closure of the Alochhaya Bioscope Co. and the Alochhaya theatre. And yet, countering London’s view of history would be to ride the nationalist wave, thereby drawing in the crowds like ants to a drop of spilt malpua syrup. The answer lay in portraying the sufferings of the prisoners in bioscopic detail—but, at the same time, making the survivors the heroes of the feature.

That I was going to play my first flawed character—anti-hero if you will, villain if you won’t—in The Black Hole of Calcutta excited me. My portrayal of Karna in The Sixth Pandav didn’t count. He was an established borderline case, a character who comes from the alluring, rare category where goodness and badness hover over a precipice, squabbling through small body movements for sheer survival. The character of John Zepheniah Holwell was blacker and without the spring of stock sympathy that epic villains like Ravana had.

As the production day approached, I was already draining myself out so as to make space for Holwell to enter. In fact, by the time we met for our pre-production meeting, I didn’t have to work at being him at all. Abani Chatterjee was oozing out, like air from a tiny tyre puncture that makes no sound. This notion of losing myself occurred from time to time even when there was no immediate acting schedule in store.

Among all these various forms and templates of humanity, I kept slipping out of me like a gas. The swift leak would continue until I told myself as lucidly as a courtroom sentence: ‘I simply inhabit this body. I am a shape-shifting man who can’t interact with this world on the basis of a fixed, agreed-upon-and-signed identity. But because of this body, I do not pass through the world like a hot knife does through butter. Instead, I clank through it and hear solid clank into solid even if the solids I speak of are words and actions, the two things that can be faked with practice.’

The script of The Black Hole of Calcutta had been hurriedly based on two separate pieces of writing, one riding on the creaky shoulders of the other. There was, of course, John Zepheniah Holwell’s own account of the Black Hole as described in his ‘A Genuine Narrative of the Deplorable Deaths of the English Gentlemen and others who were suffocated in the Black Hole’. This article published in the Annual Register, 1758 had never been seen by the two people who were given charge of coming up with the basic script, Horen Ray and myself (with additional inputs from Dinesh Boral, who was playing the role of Nawab Shiraj-ud-Daula, and from Lalji Hemraj himself). What we had carefully read was a longish entry on the Black Hole in an English encyclopedia, which heavily quoted passages from Holwell’s article, and, most importantly of all, a thoroughly researched article by J.H. Little entitled ‘The Black Hole: The Question of Blackwell’s Veracity’.

In Little’s opinion, Holwell was clearly an unreliable witness to the whole incident. The survivor of the Black Hole had, according to the scholar, creatively tampered with the truth in an attempt to pass himself off as a hero. Considering that Holwell went on to become acting Governor of Bengal, the ploy seemed to have paid off quite handsomely. Little’s article had come out only four years before, and India-watchers in London had become agitated—a rather complex word that covers the various sub-feelings of being irritated, surprised and aghast to the point of disbelief—over this bit of revisionism. In India, most people hadn’t even heard about the radical article, let alone the small ruckus that it caused in England.

A letter was sent to Little and permission was sought to make a fictitious account of the contentious event that occurred on June 20, 1756. A line from him, Lalji figured, would make the bioscope even more authentic. There was just the small matter of getting him to not mind the fact that in our fictionalized depiction of the historical event we would actually show 146 whited-up, European-seeming bodies crammed in a very small closed space—and the minor but necessary inclusion of a lady in the climactic scene. J.H. Little was a Liberal. So perhaps he would require some sort of incentive to lend his trust and support.

Shooting began with the scene in which Shiraj-ud-Daula gets the news that both the English and the French have started to build armed fortifications in a territory that he, as Nawab of Bengal, was given to rule after the death of his predecessor, Alivardi Khan. Even as the camera—with Shombhu-mama still turning the camera handle—was sucking the story in, telegraphic messages were stuttering between London and this city. Little, as we had feared, was adamant that his premise not be overturned even in a bioscope dramatization, which Lalji tried to explain was just an imaginative depiction of the Black Hole incident and not a historical documentation or recreation.

Eight days went by deciding on what constitutes a bioscope recreation and a bioscope dramatization. The uneven, twirling and inebriated type of telegrams were all kept inside a green file marked ‘Little Black Hole’ in Lalji’s office. After a longish meeting that also involved what must have been an expensive overseas telephone call, and through which nerves were getting frayed sooner than they could be repaired, it was agreed that at no point in the motion picture should there be any mention of a fixed number of Europeans in the blighted room. (The title that would have read ‘145 shahebs and 1 mem all crammed inside on a blisteringly hot night!’ was junked.)

But when Little finally got to know (admittedly, a little late in the day) that we also had an Englishwoman as prisoner inside our Black Hole, he sent a terse telegraph: ‘NO STOP NEVER STOP WONT HAVE ANYTHING TO DO WITH BIOSCOP STOP’.

At that point even Lalji, ever composed and controlled, thought that he had made a blunder by getting in touch with Little in the first place. This would now inevitably lead to a ruckus even before the bioscope was finished. Just when he was about to politely ensure that the Englishman’s involvement in the feature was cancelled, a message from London came three days after the explosive telegram from Little. This hinted, as much as a telegram can hint at things, that the scholar was willing to come to a compromise.

‘HEARD OUT BIOSCOP SOURCES HERE STOP WILLING TO MAKE MINOR RPT MINOR CHANGES TO SCRIPT’

It took less than a week to renegotiate the ‘terms of consultancy and quasi-historical approval’. Little ended up with £30 more in his kitty for willing to have his name and quote in the publicity material of The Black Hole of Calcutta, or Survival of the Fittest. That was, incidentally, a 15 per cent increase on his original fee.

It was a good thing that Little agreed because with his blessings and endorsement The Black Hole of Calcutta became the talk of the town, it drew crowds from all over the city and beyond like no other performance—theatre or bioscope—had ever drawn before, or indeed would for some years. Bholanath Chandra’s approving words in the reviews and on the flyers and posters helped, of course, by getting the bhadralok crowd interested. But, only the Englishman J.H. Little—an English scholar who, naturally, knew history in the way that only English scholars do—would draw them to The Black Hole like beggars to a zamindar’s wedding. However, it was also clear to us that what really made everyone flock to the Alochhaya theatre, and to all the other bioscope theatres across the country which had bought prints of the feature, was something else altogether: the presence of one mem among 145 men in the dungeon.

Dinesh Boral would later write accurately in his autobiography, My Silent Years: ‘Shooting was hell. There was no way anyone could speak in the heat. Even though the routine had always been to mouth something that one felt was apt for the scene despite it being a silent film, it was just too much of an effort. Horen was the only one anyone could hear speaking out loudly, commanding us, sometimes individually, but mostly as living pieces of furniture, brandishing his tapered megaphone at anyone who needed instructions. And everyone on the field of Tala—which pretended to be the vast expanse of Laldighi—did need instructions galore.

‘So in the heat, we faced the camera—one camera changing positions constantly, with the sweat-drenched Ashok Ray behind it—and acted, pretending to shout, scream, moan and speak without uttering a word. It’s hard to decide which of the two made the heat really unbearable—the sunlight beating down on us like non-stop yellow sheet lightning with no gaps in between or the huge mirrors that magnified this light and directed it on to our bodies already toasting inside the costumes. The makeup came off too soon and I think you could see it in The Black Hole’s tremendous battle sequence.’

Initially, it had been decided that we would hire a large contingent of the 125 extras who were required to play the role of the European soldiers from the Anglo-Indian community. But just before word was about to be sent out through the media of The Statesman and a few handouts at places like the Carlton, there was a change of plan. Fair and sturdy Bengalis were found and the make-up artists applied just the right amount of foundation, talcum and finely grained lacto calamine (for the palish pink hue) for them to look like shahebs—which they did only remotely even in black and white. (The silly trick of applying just foundation and topping their heads with blond wigs would not do if standards were to be set.) More than a few of them looked rather odd, like photographic negatives walking about.

It was the prison scene, of course, that the crowds actually paid good money to come and see. We knew even while making the long scene that this was going to be the point on which the whole bioscope would hinge. Out of the mammoth, till then unheard-of one and a half hours of the motion picture, a whole forty minutes were devoted to this scene. It started with the European prisoners being hoarded into the black, cobbly-walled cell. It ended with the dramatic survival of a few. But the real story within the story of The Black Hole as a whole and the prison scene in particular was undoubtedly the passionate—and illicit—love story between the two strangers, John Zepheniah Holwell and Mary Carey, one of the few women who had been left behind in the city when it was overrun by Nawab Shiraj-ud-Daula’s forces.

Durga, who played Mary, was uncomfortable before the scene. She was to partially bare herself not only in front of the people around her on the sets but also before an unending stream of people whose character, identity and proclivity towards tastefulness she would never know. Sounding almost like a flesh-and-blood version of J.H. Little’s exclamatory telegraphic messages, Durga had shown signs of acute nervousness by spluttering before the day of shooting approached.

‘You know Alochhaya would not do anything that isn’t artful,’ I had told her one day when she was on the verge of chewing up her lower lip.

‘You have no idea about the risks that I face, playing an Englishman who is considered a rogue by the whole country,’ I went on. ‘But you know why I’m risking it? I’m risking it, Durga, because this will be big. I just know it, and these are not Lalji’s words. I just know it.’

I can never be sure whether it was my small pep talk or Lalji’s clever ploy that made her give in: Lalji had been the source and at the forefront of rumours doing the rounds in Alochhaya about the studio seriously considering someone else—some Nadia from Bombay—for the coveted role of Mary Carey. But who should take the credit is inconsequential. Durga agreed. Which, you must admit, was brave of her. For not only would she have to reveal more of her body than any other woman in Indian bioscopes had ever done, she would have to do this pretending that she was an eighteenth-century European woman too busy fighting for her life to think about her modesty.

It was a very crowded space that Durga and I entered. She was wrapped in a loose bedcover underneath which she wore a white dress that she had practised peeling off several times alone in her room as well as a few times in the trusted company of another Alochhaya regular, Bimala. I was told that she had had two large gins before coming out of her room with makeup and costume. If the gin helped, it hadn’t hidden her discomfiture totally.

The awkward, slightly ridiculous, fact that there were a large number of people who didn’t have to do anything but writhe about in an extremely close space was eclipsed by the more overwhelming fact that I would be in intimate physical contact with Durga. We were to be so close, so intermingled in body and limb, that I felt unsure where the pretending would end, where the loss of control begin. A man with a powder puff gave me one final powder puff and a quick flurry of dabs of thickened water faking as sweat. The powder and the water miraculously refrained from mixing and as the mirror flitted away, I caught a dour-looking old-style Englishman scowling back at me with visible derision.

There are many things that a good actor can pretend at with great conviction. Love, hate, funniness, physical pain and being unloved—these being the basic five. (Relief, thankfully, was a theatre device, and if required to be recreated in a bioscope was effectively taken care of by a pair of wide eyes and a mopping of the forehead with a white handkerchief or clothes-end.) With talent and practice these five pretend-emotions could be conjured up to inhabit the face and the rest of the body like jewellery on women. But acting is not only about conjuring up emotions and gestures that wouldn’t otherwise exist. It’s also about directing the flow of existing feelings, like cupping running water and redirecting into the mouth for the purpose of drinking.

Inside the narrow set, illuminated by spotlights carefully placed to stretch individual shadows to their physical limits and make them sprawl on each other, I was expected to display physical discomfort. It didn’t help at all that Durga looked beautiful. She just stood there, diffident and a little vulnerable, at the edge next to the camera, waiting for the shot to be shot.