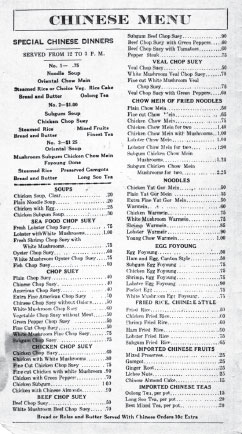

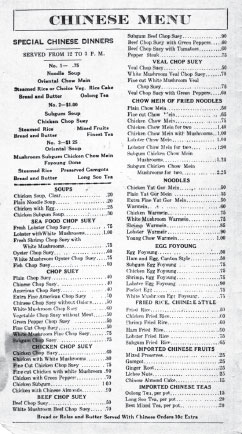

Chinese menu, the Pagoda; right: American menu. McClung Historical Collection.

ARCHIE RHEA’S, AMERICAN CHOP SUEY AND THE LEGACY OF MARGARET HUMES

The name Archie Rhea’s Tavern may not be well known to many, but it was the first commercial business in the building that most everyone familiar with Knoxville now knows as the Bijou. The original section of the building was begun in 1815 by Knoxville merchant Thomas Humes, who, unfortunately, passed away while it was being built.

Thomas Humes was born in Ireland in 1767 but immigrated to the American colonies as a child. He settled in Knoxville around 1795. Humes bought part of James White’s Lot 38 of the original division of the city in 1801 and began establishing himself as a merchant. Humes has been described as a man “universally loved and trusted for his strict probity and kindly, benevolent disposition.”

Humes opened a store on his property on Gay Street and did a thriving business in Knoxville, where little manufacturing existed at the time but where trade was reported to be brisker and shops better stocked than in Nashville. In 1805, he bought additional land in Lot 38 with plans to build. Humes had married Margaret Russell Cowan, and they, with their five children, were living in his store building. There was a delay with the construction, and Humes never had the opportunity to see the building completed. He suffered from an infection and died on September 23, 1816.

Thomas Humes died with a total of cash on hand of over $20,000 and outstanding accounts owed to him at nearly $50,000. Although Humes died a wealthy man, leaving his family in a comfortable situation, you’ve already heard about those East Tennessee businesswomen. The savvy Margaret Humes was able to continue with the construction of the new building, and although it may have originally been intended as a private residence for the Humes family, she insisted that it was built specifically with the purpose to be used as a tavern. Her persistence paid off when she was able to obtain a lease with Archibald Rhea, the son-in-law of John Sevier, to move his tavern from Market Street to the new space.

The Humes building was considered a modern and even pretentious structure at the time of its completion and contained all the conveniences available in the best hotels in the country. The building was designed in the prevailing Georgian style—a three-story building with a basement or cellar, with a central hall running through it and rooms on each side. Basements were important features in buildings of frontier towns for the storage of supplies coming in.

Years later, the city completed a public works project on Gay Street. The north end of Gay Street was raised from the train depot by use of viaducts, and this south end of Gay Street was lowered, making the main road in hilly Knoxville more even and easy for travel. This heavy grading of Gay Street converted the basement of the Humes building into a ground floor, as we know it now. The bricks used for the building were molded by hand at a brickyard in what we now know as the Bearden District. They were hauled to the site on Gay Street on wagons drawn by oxen. On the southern façade, there was a second-story veranda that faced a large open space, or the inn yard, where stagecoaches could drive in from the road.

An ad run by Margaret Humes provides further description of the building:

The house is much larger than any other in East Tennessee, is in the centre of business, and well constructed for a TAVERN for which purpose it was built. The building contains thirteen spacious ROOMS besides the BAR ROOM, in each of which is a Fire place. The BALL ROOM and DINING ROOM are both very large and each have two fire places. Attached to the House are two commodious STABLES, an OUT LOT, GRAINARY, TWO KITCHENS and every other necessary building. Suffice it to say, that taken altogether, it is as well calculated for business as any in the western country will always command the principal business in the place, and cannot fail, if judiciously conducted, of realizing a profit to the tenant.

Archie Rhea’s Tavern and the Knoxville Hotel opened in the space in 1817. In his advertisements, Rhea assured those planning to patronize the tavern that his attention would be particularly devoted to render their situation easy and comfortable. Elegant rooms would be supplied with some of the day’s most respectable newspapers for his guests’ perusal.

Rhea’s Tavern quickly became the center of Knoxville’s social life. In addition to the bar and dining offerings, the building also hosted many other social gatherings. A school of dancing was opened in the facility, and a “practice ball” was held every other Friday at six o’clock in the evening in Mr. Rhea’s Ballroom.

The grandest celebration held at Archie Rhea’s Tavern was for Andrew Jackson in March 1819. News of Jackson’s impending arrival had reached Knoxville, and a delegation specifically appointed for the purpose was assembled to meet him on the road. An elegant dinner for upward of 120 men was prepared by Mrs. Rhea for the occasion, and festivities continued until midnight.

By 1821, Margaret Humes was advertising the building again for rent. The building then passed through many different hands and operated under different business names. The name that lingered the longest was the Lamar House Hotel. It was suggested to the then proprietor, Sampson Lanier, that the name Lamar be used in honor of Gazaway Bugg Lamar, who showed a financial interest in Knoxville in the 1850s. He purchased Knoxville municipal bonds, most likely issued to finance the railroad development. He also, along with several other New York investors, was responsible for building a suburb north of the East Tennessee and Virginia Railroad tracks. Lamar had established himself in factories, shipping, insurance and warehousing. During the Civil War, he was active in supporting the efforts of the Confederacy by founding the Importing and Exporting Company of Georgia, which was one of the blockade runners of the war. He dealt extensively in guano (a type of fertilizer), cotton and tobacco.

The Humes building survived the ravages of the Civil War by its occupation as a hospital, first by the Confederacy and later by the Union. The most well-known name associated with the hospital was that of Union general William P. Sanders. Sanders had a bit of a rough start in his military career. His letter of dismissal from West Point was written by the then superintendent of the academy, Robert E. Lee, based on Sanders’s accumulation of demerits, his deficiency in academics and his general want of application. Sanders managed to stay on and graduate from West Point by some help from United States secretary of war Jefferson Davis, who happened to be Sanders’s cousin.

Sanders’s initiative and bravery became apparent during the war, as the Kentucky-born and Mississippi-raised man with Southern leanings fought for the preservation of the Union. In 1863, General Ambrose Burnside chose Sanders to lead a raid into East Tennessee, urged by President Lincoln, who considered the area both politically and militarily important. It is noted that in this area of the country, one of the great tragedies of the Civil War was that it was often brother against brother, which was the case for the Sanders family. During picket duty along the Tennessee River, Sanders made a request to headquarters to see if he might be allowed to write a letter to his brother, who was serving in the Confederacy, and leave it where the Rebel cavalry might find it and forward it on.

Burnside had given Sanders the orders to hold off incoming Confederates while fortifications were dug around Knoxville. While making their stand about a mile from the entrenchments, on a high hill on Kingston Road, Sanders was wounded by a sharpshooter and taken to the hospital at the Lamar House, where he later died. In yet another tragedy of the war, the Confederates were under the command at the time of Colonel Edward Porter Alexander, who had been Sanders’s classmate and roommate at West Point. Sanders was buried at night, under the cover of darkness, to keep the news from demoralizing his troops.

Generals William Sherman and Philip Sheridan reportedly laid out battle plans on the dining room table of the Lamar House. General Sherman provided some insight into the food of Knoxville during the war, writing that, arriving in Knoxville and crossing the river by pontoon, they saw a large pen with a fine lot of cattle. Sherman was surprised to see that General Burnside had taken up headquarters in a fine mansion on Kingston Pike, where the officers were treated to a roast turkey dinner, complete with a regular dining table, a clean tablecloth, dishes, knives, forks and spoons, which was an experience that Sherman had not encountered during the war. After Sherman exclaimed that he had reports of the troops starving, Burnside explained that he had communication with a settlement of Union sympathizers on the south side of the river, who had supplied him with a good amount of East Tennessee staples: beef, bacon and cornmeal.

Thus far, five United States presidents have been guests in this building: Andrew Jackson, James K. Polk, Andrew Johnson, Ulysses S. Grant and Rutherford B. Hayes. The stopover of Rutherford B. Hayes in September 1877 marked the heyday of the social era of the Lamar House. A luncheon was prepared by Mr. and Mrs. James Cowan. Following lunch and a speech given by Hayes, the public was invited to meet and shake hands with the president. He spent two hours greeting the enthusiastic Knoxvillians. That evening, Hayes enjoyed a presidential dinner at the Lamar House, followed by an excursion across the river to a dance at the farm of Perez Dickinson’s grand Island Home. Dickinson was a partner in the extremely successful Cowan and McClung wholesaling business. He was from Massachusetts and a cousin of the poet Emily Dickinson.

The Lamar House’s position in the community had begun to slowly erode as the railroad developed. Newer, larger and more modern hotels offered comfortable lodging and fine dining, as the commercial activity with the wholesaling warehouses moved city activity north along Gay Street and Jackson Avenue.

In 1908, the ballroom of the Humes building was converted into a theater. The new Bijou Theater opened to a sold-out crowd in 1909, with a production of Little Johnny Jones starring George M. Cohan. The Bijou was one of the first theaters in the area to admit both black and white guests. Black patrons had a section in the gallery and entered from a set of stairs near the side of the building. The Bijou enjoyed a run of many successful live theatrical performances.

Construction began in 1926 on the Tennessee Theater, a few blocks down Gay Street. The owners of the Tennessee also bought the Bijou Theater but sold it to an area businessman with the stipulation, or a non-compete clause, that the Bijou would not be used for theatrical productions of any kind for the next five years.

During the era of prohibition, the Bijou Theater became the Bijou Fruit Stand. This “fruit stand” was noted as one of the first establishments in Knoxville to sell bananas. The new, unusual and exotic fruit sold for ten cents each.

In 1934, Knoxville’s first Chinese restaurant, the Pagoda, was opened by Max Weinstein in the space. The Pagoda featured an extensive American menu of oysters in season, relishes and appetizers, soups and broths, fish and shell fish (trout, mackerel, shad, snapper, pompano, lobster and shrimp), steaks, veal cutlets, lamb chops, pork chops and tenderloin, fried or broiled ham or bacon, eggs, spaghetti, cold meats including tongue and Chinese roast pork, salads, sandwiches (even a goose liver sandwich), vegetables, seven preparations of potatoes, desserts, cakes, fruits such as “ice cold” watermelon and four preparations of toast. The Chinese menu included multi-course Special Chinese Dinners of soup, entrée, steamed rice or vegetable, bread and butter and oolong or long soo tea. Seafood chop suey and multiple versions of chicken, beef, veal and even an American chop suey were offered. Other offerings on the Chinese menu were noodles, egg foo young, fried rice and an imported Chinese fruits section, including gamgot, ginger root, lychee nuts and Chinese almond cake.

Chinese menu, the Pagoda; right: American menu. McClung Historical Collection.

In 1935, Paramount Pictures took on a thirty-year lease for the Bijou, showing second-run and hold-overs of movies that had previously been shown at the Tennessee. But by 1965, Paramount chose not to renew, and the theater became the Bijou Art Theater, an adult, or X-rated, movie theater.

The rooms of the Lamar House were declared a public health hazard and closed in 1969. The theater, however, continued to operate. In an odd turn of events, in 1971, the Bijou was bequeathed to Church Street United Methodist Church. As newspaper articles began to surface that the church owned a property where burlesque dancing was taking place, the church quickly sought to sell the building.

By 1975, the Bijou Theater had been closed due to unpaid rent and taxes and was slated for demolition. This time, however, the citizens of Knoxville would not be denied. The same year, the Bijou was added to the list of the National Register of Historic Places. A group of concerned citizens assembled, calling themselves Knoxville Heritage—now known as the leading preservation group, Knox Heritage—and launched a campaign to save the Bijou. The theater reopened in 1977.

After years of the community’s dedicated attention, continued fundraising efforts and strategic planning and restructuring, the Bijou Theater rose to its height of popularity with regular performances by the Knoxville Chamber Orchestra, Americana and bluegrass musicians, classic and folk rock groups, comedians and one-man shows. The theater was built before amplification, and music writers and journalists passing through town have often commented on the wonderful acoustics at the Bijou. The booking for the wide variety of acts for the Bijou as well as the Tennessee Theater was taken over by A.C. Entertainment, which also produced Louisville’s Forecastle Festival and the massive Bonnaroo Music and Art Festival in middle Tennessee. The Bistro at the Bijou, one of the first downtown projects of preservationist Kristopher Kendrick, opened in 1980 and is now owned and operated by esteemed restaurateur Martha Boggs. Two hundred years later, Margaret Humes’s assertion that a wellmanaged business in this space would be successful has been fulfilled many times over. And as I overheard Martha say the other day, “Now it’s our turn to take care of it for a while.”