Alhambra Court. Dexter Press.

TRAVELERS, LUNCH COUNTERS, SIT-INS AND DESEGREGATION

By 1944, Franklin D. Roosevelt was focused on East Tennessee again as the Great Smoky Mountains National Park was being created. Logging and clear-cutting of the late 1800s began to destroy the beauty of the area, and locals and visitors joined together in an effort to preserve the land. John D. Rockefeller donated $5 million and the United States government added $2 million, and the tracts of land were assembled to form the park. The 500,000-acre wonder is now the nation’s most visited national park.

FDR and other officials and dignitaries stayed at the Andrew Johnson Hotel in Knoxville as the park was being established. The kitchen at the Andrew Johnson packed a “sumptuous southern picnic lunch” for the entourage for the trip to the mountains to tour the park, which included caviar and cheese sandwiches, fried chicken, crab salad, sardines, crackers, fruit and several kinds of bottled soft drinks.

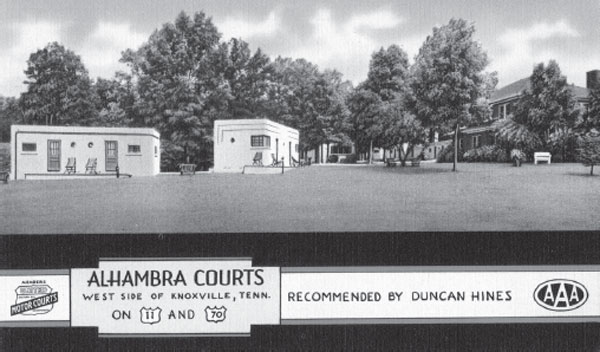

Motorists across the country were ready to travel and explore the Great Smoky Mountains, the American South and the popular tourist destinations of Florida and the coast. Knoxville became a frequent stopping point for many travelers, as it was at the junction of Dixie Highway, U.S. 70 and Lee Highway, U.S. 11, a halfway point for many vacationers. Restaurants and tourist court motels sprang up all along Kingston Pike and Chapman Highway.

The Alhambra Tourist Court at 4249 Kingston Pike was run by George Fooshee and recommended by famed traveling salesman and author Duncan Hines. Terrace View Court, at 6400 Kingston Pike, was owned by Fooshee’s brother Leon and was situated at the top of Bearden hill, where “there is always a cool breeze.” Each room was said to have a view of Mount LeConte and the majestic Smoky Mountains and featured fine furnishings from Sterchi Brothers Furniture Company.

Alhambra Court. Dexter Press.

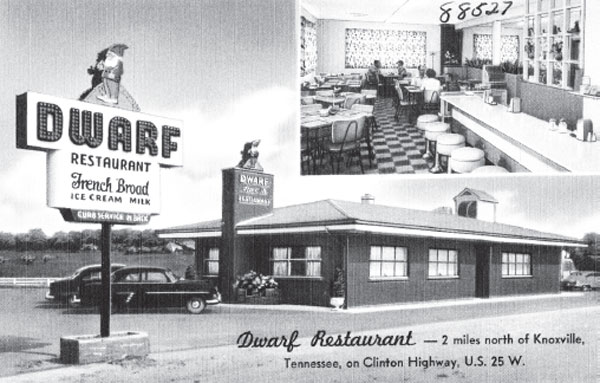

Highland Grill was recommended by AAA and featured steaks along with the southern staples of fried chicken and country ham. The Dwarf Restaurant advertised local French Broad milk and ice cream, a chicken and dumplings dinner or “French fried ocean catfish” dinner for one dollar, while the Dixieland Drive-In offered a specialty called Chicken in the Rough, the world’s most famous chicken dish of the time, according to National Restaurant magazine.

Chicken in the Rough was one of the earliest food franchises, developed by Beverly and Rubye Osborne in 1936 while on a road trip themselves. Beverly spilled their picnic basket full of fried chicken when Rubye hit a bump driving through the Oklahoma prairie, and they declared it was truly “chicken in the rough.” The dish Chicken in the Rough consisted of half of a golden fried chicken, heaps of shoestring potatoes, hot buttered rolls and a jug of honey. The chicken was specifically served unjointed, without silverware and in aluminum containers that would keep the chicken hot for hours. The Dixieland Drive-In became the fourth-largest purveyor of Chicken in the Rough in the country. Special machinery was designed that could simultaneously fry and steam the chicken.

The Dwarf Restaurant. Manning Graphic Arts.

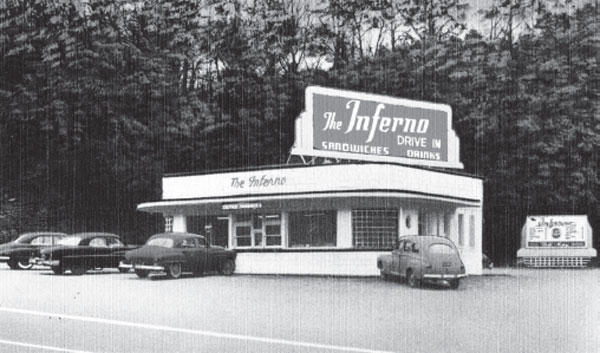

One of the most unusual eateries of the time was the Inferno Drive-In, which was first opened on Blount Avenue, between the Henley and Gay Street bridges. The original Inferno was very small and only had a half dozen bar stools. It reportedly had a red neon light out front that formed a devil, horns, a pitchfork, blazes and a jiggling fire. The Inferno was the home of the “devil dog,” a hot dog covered with a special chili. It was later moved to 2819 Chapman Highway, on the way to the Smokies. Keeping with the theme, the Inferno provided matchbooks to customers with the phrase “Go to the devil” printed on them.

Although travelers were on their way to some of the most beautiful spots in the country, in 1947 travel writer John Gunther noted that Knoxville was the “ugliest city I ever saw in America” in his book Inside USA. After one of my tour groups asked me to relate that story, we all burst out laughing, as of course now Knoxville constantly receives compliments on its natural beauty and cleanliness. One can’t help but wonder if Gunther’s sour disposition was caused by his discovery that Knoxville served beer no stronger than 3.6 percent alcohol and that the taprooms closed at 9:30 p.m.

While folks in this area would naturally do this anyway, in 1952 locals were encouraged to be kind to tourists through a Courtesy Campaign, which was accompanied by a contest created by the Knoxville Tourist Bureau and promoted by the local newspapers. The week of August 17, 1952, C.B. Alexander, superintendent of the Oliver King Sand and Lime Company, received a cash prize of twenty-five dollars from the Dempster Brothers Company for being the most courteous person in Knoxville. Even the person nominating the recipient received an award. Alan Cruze received six Arrow shirts from J.S. Hall for nominating Alexander for always directing tourists who accidentally turned into the sand company on their right way. He noted one particular incident when a couple from Florida turned into the sand company, quite a bit away from their destination of the Alhambra Tourist Court. Alexander politely gave them directions and then encouraged them to come back again someday. Other prizes offered during the courtesy contest included an electric clock radio from Kimball’s, a six-month pass for two to the Tennessee Theater and an RCA table model radio from Woodruff’s.

The Inferno Drive-In. Standard Souvenirs.

Despite Gunther’s blatant insult, tourism in Knoxville continued to grow, even as the rest of the country was reporting a decline. In 1954, Knoxville reported its biggest numbers up to then of tourist trade. That year, 1,326,611 out-of-state tourists came through the area, while 1,200,268 Tennesseans from across the state visited. The majority of tourist dollars were spent on food, with total food spending at $9,717,956.

Gunther’s unpleasant remarks also prompted the Knoxville Garden Club to establish the Dogwood Driving Trails in 1955. There are now trails in all parts of the city, and our Dogwood Arts Festival hosts arts and cultural events all through the month of April, encouraging folks to come and enjoy the beauty of Knoxville.

Sterchi Brothers Furniture Café. McClung Historical Collection.

Meanwhile, downtown Knoxville continued to thrive. Folks often wanted a fast, convenient lunch while in town doing errands or shopping, which gave way to the rise and popularity of lunch counters. Pharmacies and department stores such as Walgreens, Woolworth’s, Kress, Miller’s, Rich’s and even Sterchi Brothers Furniture Company provided lunch counters for their many customers.

A quick meal at a lunch counter might include cold, toasted or grilled sandwiches. BLTs, burgers, patty melts, hot dogs, club sandwiches, bacon and egg sandwiches, grilled cheese or grilled ham and cheese sandwiches with fries or onion rings were typical menu items. Soups, salads with cottage cheese, tuna salad–stuffed tomatoes, egg or chicken salads were lighter fare. Desserts were specialties of fruit or cream pies, ice cream sundaes, banana splits, floats, sodas, milkshakes and malts. Miller’s Laurel Room was particularly known for its soft and airy fresh coconut cake with lemon cheese icing and Chef Henry’s Heavenly Hash, a gelatin salad.

Kress lunch counter. McClung Historical Collection.

A favorite dessert at the Knoxville Kress was the fruit and nut pudding. The recipe request amused the kitchen staff at Kress, who let the secret out that the famous fruit and nut pudding, in the true Appalachian style of using what was available, was made from day-old doughnuts or stale cake and leftover fruit pies. The recipe is as follows:

Save up stale cake or doughnuts, fruit pies and the juice from 1 can of peaches in an empty whipped topping container in the freezer until the container is full. Combine contents of container with one 10-ounce package of frozen strawberries and perhaps a crumbled slice of bread. Add 1 teaspoon almond flavoring. Optionally add nuts or red food coloring.

Heat the mixture in the saucepan, then spoon into a serving dish. Top with a hard sauce or whipped cream.

Early in 1960, segregation was being challenged by sit-ins at lunch counters. After the first sit-in occurred in February in Greensboro, North Carolina, word spread quickly, and a group of Knoxville College students organized to conduct their own sit-in at one of Knoxville’s lunch counters. The college’s president convinced the students to wait until he had a chance to talk with city leaders, hoping to avoid the violence of protests occurring in other cities. Knoxville’s mayor even went so far as to take a delegation of himself, two chamber of commerce officials and two Knoxville College students to attempt to meet and negotiate with chain store executives in New York to desegregate their lunch counters in Knoxville. They were unable to obtain a meeting, and the Knoxville protests began in June. Some of the Knoxville sit-in experience is documented in Merrill Proudfoot’s book Diary of a Sit-In.

In 1963, the Committee for Orderly Desegregation of Public Facilities in Knoxville and a committee of the Knoxville Restaurant Association formed an agreement for restaurants to desegregate in Knoxville on July 5. Thirty-two local restaurants participated, including Regas, the S&W Cafeteria, the Rathskeller, Pero’s, Louis’, Wright’s Cafeteria, the Tic-Toc Room and Helma’s.

Helma’s was located on the Asheville Highway, at the junction of 11E and 25W, about twelve miles east of downtown Knoxville. Helma Gilreath began her eatery in 1949 in a so-called truck stop style with two tables and six stools. She eventually established a country-style buffet that was so successful that she was able to expand to a dining room that accommodated 125 plus banquet rooms for 330. Helma once catered a meal for 5,300 employees of the local Magnavox manufacturing plant and also provided catering for the movie All the Way Home for scenes shot in the Smoky Mountains. A flavor of locally produced Kay’s Ice Cream was patterned after Helma’s famous banana pudding, and in 1985, she appeared in the pilot of an early reality show of a television series called Wish You Were Here, featuring Hee Haw variety show favorite Kenny Price. The premise of the show was that Price and his wife would travel the country in an RV and take viewers on a tour of various campgrounds and other places of interest. Helma was named Tennessee’s Outstanding Restaurateur of the Year by the Tennessee Restaurant Association in 1977.

Helma was one of the committee members who attended every Restaurant Association meeting and stated that segregation in restaurants should be addressed. Everyone agreed that it should not be a problem, as East Tennessee was not as racially divided as other cities of the deeper South. When the first black patrons pulled up at Helma’s, a nervous server asked, “What do we do, what do we do?” Helma calmly replied, “What do you normally do when we have customers?” The following year, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which banned racial discrimination in voting, employment and use of public facilities. Helma’s daughter related how, several years later, in the mid-1970s, University of Tennessee basketball great Bernard King came in to eat at Helma’s, and many of the white men argued over who would get to buy his lunch. Knoxville, and the country, had come a long way.