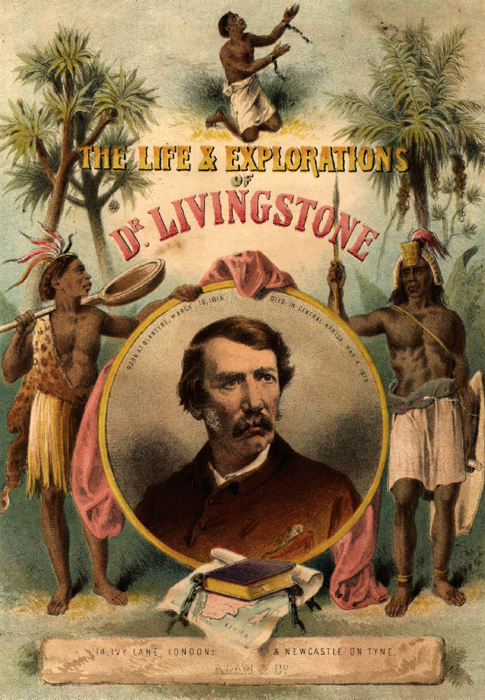

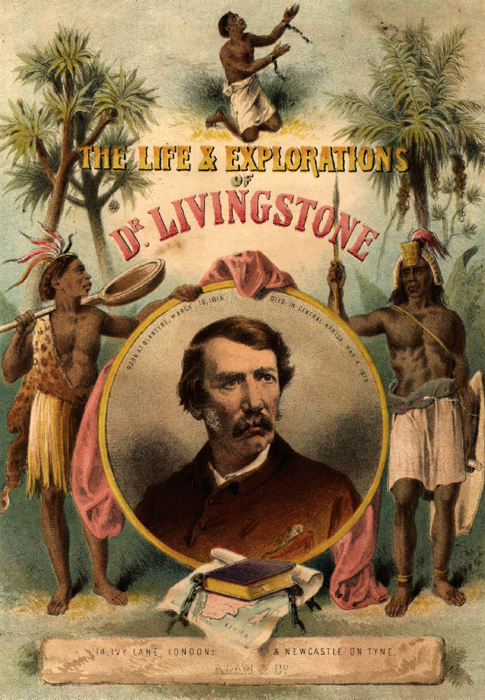

David Livingstone (1813–1873), Paul Ehrlich (1854–1915)

European exploration and colonization of much of the world began in the late fifteenth century, but it was not until almost 400 years later that attention focused on the neglected interior of the African continent. The attraction of rich, untapped natural resources outweighed the challenges of deserts, jungles, hostile people, and unique, devastating diseases.

COMBATING SLEEPING SICKNESS. African sleeping sickness, or trypanosomiasis, has long been a significant health problem in the hot and humid regions of central and southern Africa. The disease is caused by several species of trypanosomes—spindle-shaped protozoa with trailing flagella—and transmitted by the bite of the tsetse fly. The primary victims are humans and domesticated cattle, and they invariably die in a state of profound drowsiness within months if not treated.

One of many sleeping-sickness epidemics occurred in the Congo region from 1896 to 1906 and claimed some 300,000 to 500,000 human lives. This episode served as an impetus for European medical scientists to develop an effective treatment and coincided with the early years of treating infectious diseases with synthetic chemicals.

In 1858, the Scottish medical missionary and African explorer David Livingstone—immortalized by the New York Herald correspondent Henry Stanley’s supposed greeting, “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?”—proposed using Fowler’s solution (potassium arsenite) for the treatment of sleeping sickness. In 1905, the more effective and safer organic arsenic compound Atoxyl was found useful. Atoxyl failed to live up to its benign name, however, causing blindness via damage to the optic nerve. In the early 1920s, the Atoxyl derivative tryparsamide was developed at the Rockefeller Institute, and when used in combination with suramin (Bayer 205; Germanin), it remained the treatment of choice for sleeping sickness for four decades.

While seeking safer and more effective organic arsenic compounds than Atoxyl for sleeping sickness, Paul Ehrlich redirected his efforts and discovered arsphenamine (Salvarsan) in 1910, the first cure for syphilis.

SEE ALSO Salvarsan (1910).

The medical missionary–explorer David Livingstone was among the first Westerners to travel across the African continent—a journey impeded by the prevalence of malaria, dysentery, and sleeping sickness, for which he recommended Fowler’s solution, an inorganic precursor to the organic arsenical, Atoxyl. In his well-publicized writings, he actively supported the abolition of slavery.