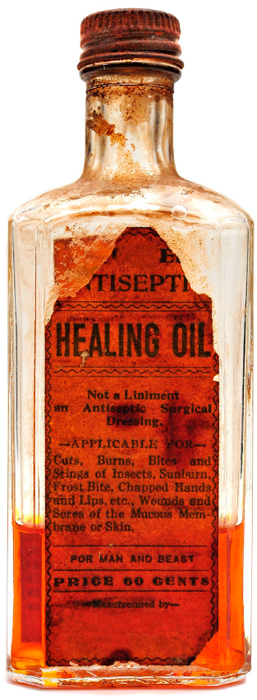

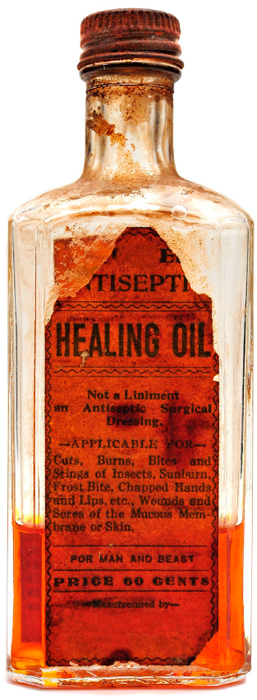

GOOD ADS TRUMP SOUND SCIENCE. Patent medicines are not patented medicines. Patents provide inventors exclusive rights to market their product for a limited time in exchange for a public disclosure of their invention. The designation patent medicines was based on the “letters patent,” granted by the English Crown during the seventeenth century, which gave the maker exclusive rights to that formula and a royal endorsement in their advertising—a practice codified by the Statute of Monopolies (1623). However, although most of these medicines were trademarked, few were ever patented. To do so, the maker would have been obliged to disclose the secret ingredients, some of which were of dubious effectiveness or potentially harmful.

Capitalizing on the belief that American Indians were healthy and “at one with nature,” many patent medicines bore American Indian names and contained supposed healing plant parts. Notwithstanding claims to the contrary, nineteenth-century patent medicines often contained addictive alcohol and narcotics.

The success of patent medicines in the nineteenth century was closely linked to the rise of the advertising industry. Products bearing inventive names were advertised in newspapers and mail-order catalogs and were purported to cure virtually all disorders afflicting humankind, without exception or qualification. Not burdened by legislation requiring makers to demonstrate the effectiveness of their products, advertisements relied upon endorsements by famous public figures and testimonials by supposed long-suffering (and now cured), grateful users. Medicine shows, traveling primarily to the midwestern and rural southern United States, presented entertainment acts and celebrity appearances, interspersed with promotions of “miracle cures.”

During the early twentieth century, investigative journalists exposed the health hazards and addictive properties of many patent medicines. These articles led to the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act in 1906. Over the years, while the familiar and lucrative trade names of patent medicines were retained, medical claims were restrained and formulas were modified to remove unsafe or ineffective ingredients.

SEE ALSO Pure Food and Drug Act (1906), Food and Drug Administration (1906), Placebos (1955), Dietary Supplements (1994).

“Snake oil” was a derogatory designation that referred to quack medicines widely promoted during the nineteenth century in the United States. Such products, containing undisclosed ingredients, were expansive on claims of effectiveness and silent on potential dangers.