Fixity, footpaths, gypsies and vagabonds

‘The malefactor is first disobedient to God, and afterward injurious to himself,

and last of all, a wolf and an enemy to the commonwealth’

There are no curtains on the window, so when I wake and my eyes open I see the room filled with the deep violet of outside. It is a bright darkness, just before dawn, and a car alarm is sounding somewhere in the trees. Sunk deep in the pillows, I’m guarding my slumber, but the noise is so irregular it snags me. It’s not an alarm, it’s a song thrush, and every phrase that pours out of him is different, a crazed raga. He’s loud, manic and randy as hell, and I assume by the background silence that every other living creature is willing him to stick a sock in it.

When I wake again, it is the dog. He’s standing on the bed, circling and whining, doling his eyes, cocking his head, doing everything he can to urge me up and out. We’re late: he needs me to focus and hit the ground running. But I put the coffee on and he circles the kitchen in sheer disbelief. I stuff some toast into my mouth, an apple into my pocket and, as experience has taught me, only pick up the lead at the very last minute.

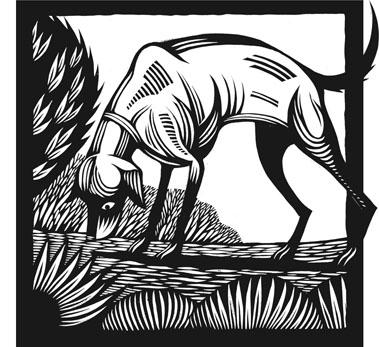

I open the door and he darts through, runs ahead of me, and I whistle him back to clip on his leash. He is beside himself with excitement, all aquiver, straining at his collar, but when we turn onto the common his muscles relax, his body transforms. And he runs, head low to the ground, whipping through the grass, his nose planing the trail, scanning for scent. The urgency is cast aside, the business has begun.

The dog sniffs piss like a doctor listens to a heartbeat. He savours it like a sommelier. He might take several short sharp inhalations, turning his head to smell under the thatch of grass, where the piss has pooled and concentrated, or he might take long drafts from the root, drinking its scent with relish. Every now and then, and never wantonly, he will piss on top of the smell: a judicious squirt. It is a widely held fallacy that dogs do this to mark their territory, but the action seems less like hammering in a sign that says mine and altogether more like commenting on a friend’s Facebook status. In fact, the whole song and dance of it up and down the hedgerow seems a lot like checking your phone in the morning before work. A friend of mine calls it checking his weemails. It’s an information exchange.

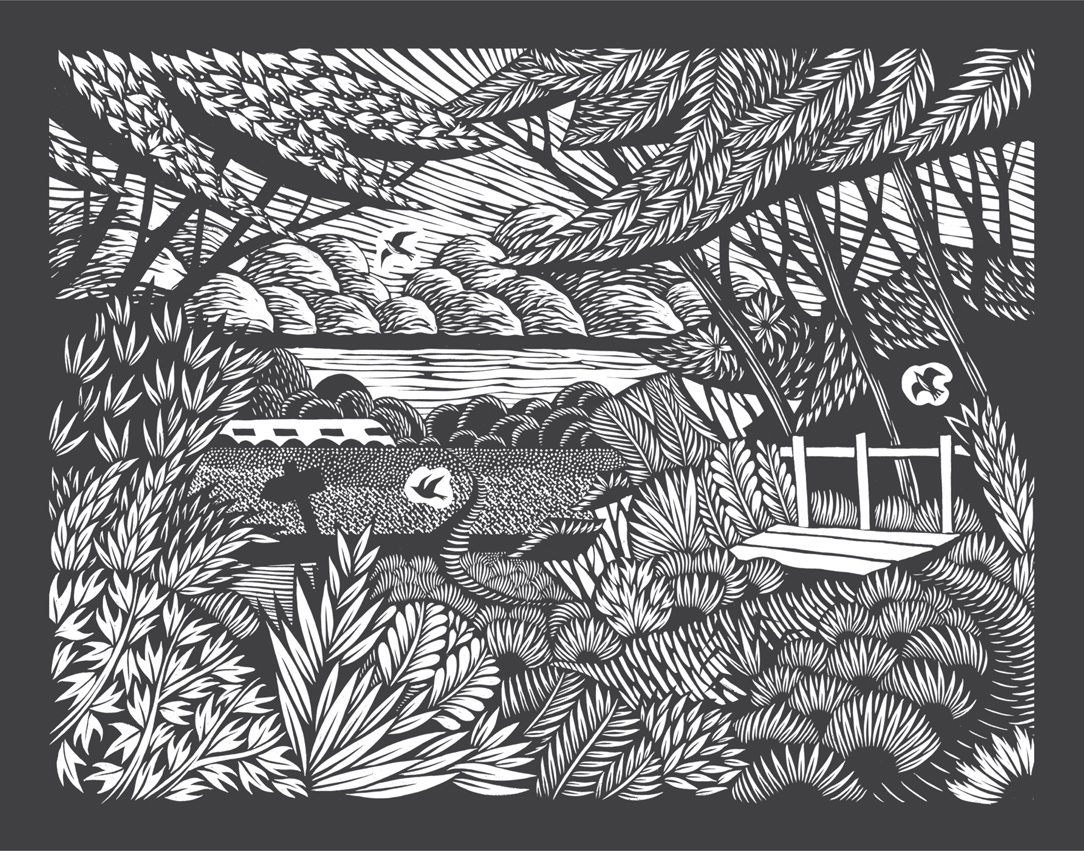

So with the dog online, busy streaming last night’s piss bulletin, I have a moment to wake up. Mellis Common rolls out before me, 150 acres of common land, unchanged for centuries, an inland lake of long grass blustering in the strong wind, a nature reserve of orchids, clover and fern. It bristles with motion: starlings flit constantly in and out of the scaffold of large clumps of hawthorn, the hedges rustle with rabbits and large squelchy depressions in the clay, fenced off by their own spurge of bulrushes and nettles, are home to newts and mink and snakes. It is Virgil’s nostalgic vision of nature, where the only fences are temporary, to keep in the hulking Charolais cattle and the gypsy cob horses.

In 1968, the writer Roger Deakin moved into a deserted farmhouse on the perimeter of this common. Setting up home in a skeleton of a Tudor farmhouse, he rebuilt the house around him as he slept on the floor. His diaries, Notes from Walnut Tree Farm, reminisce the moment he and his friends were settling in to the task, camping in the garden and making fires in the evening: ‘We were on the margins, les marginaux, and we identified with the gypsies in a romantic and starry-eyed way.’ Later on in his Notes the gypsies appear again, this time stepping out of his imagination and onto the Common: ‘We talked about the recent gypsy invasion – visitors from another planet – an alien landing – and what to do about the mess they left behind – Calor-gas cylinders, old boots, clothes, skirts, plastic bags, fag ends, fire sites, drink cans etc.’

These two sketches are resonant of a common bipolar sentiment towards travellers – on the one hand, a resentment of their arrival ‘from another planet’, on the other, an exoticism, a starry-eyed romanticism, the glamour of the open road. In popular culture, gypsies exist in newspaper reports about squatted patches of wasteland and in romance novels about middle-class sexual repression – and barely anywhere else. With their own voice rarely heard, they are projections of the society that labels them, of a suspicion that runs past them to a deep seam of othering. It is a simultaneous fear and fascination of un-rootedness, the danger of a class of person defined entirely by their motion both through, and outside of, the fixity of property: the vagabond.

With the dog at my heels, I turn off the common. The byway is worn and uneven: it undulates as much as it twists, roping alongside the paddocks belonging to the farm. The greenery either side of it is the remnant of ancient woodland, the forests that carpeted Britain after the Ice Age. Thick bands of dog rose hang like vines from the trees whose branches intersect over the path like the folded fingers of a chess player. The sky is rumbling, thunder is approaching and the light is bright in puddles among the tiger stripes of shadows that lace the path. A gust runs through the length of the tunnel, tugs my hair, and, at the mouth of it, the slatted wood gate of the railway line burns white.

I cross the railway line with the dog yanking on the leash. With the gate shut behind me, I let the leash extend to its full length and watch the dog hustle into the field like a boxer from his corner. The path crosses the wide field, exposed to the miles of farmland around it, and the wind is roaring in my ears, snatching at my jumper like a slack sail. The sky is spitting. There’s an iron-hued anvil of cloud above us and the dark columns of rain on the horizon suggest the storm is about to break.

We duck into the wooded area of the path which runs for a mile further to the main road, a nice walk lined with fields and private woodland. The path is our right of way, neatly signposted for our convenience, but to step off it, to follow the deep tyre tracks of tractors sweeping into the fields or to slip through the blackthorn into a glade, is to break the law. But this is where the magic is. So just before the pink-washed house with a pond and the massive weeping willow, there’s a turning into a field. The sign that said KEEP OUT has long been buried in the bramble so we take the more direct route to the trees, to Lady Henniker Woods.

The Hennikers are a family of merchants, politicians and military men, who once owned 30,000 acres in East Anglia. Their estate has now shrunk to a tenth of that, but still includes their ancestral seat, the manor house to the west and all the woods and farmland within walking distance. They are well liked, and have opened up their land to public use: they sold the common of Mellis to the local wildlife trust and the majority of paths that cross their land, though not public Rights of Way, are permissive paths, ones they have opened up to the public – but this could be reversed the moment the property changes hands.

We cross the fallow field to the woods and the dog, snaking about in front of me, disturbs a large hare, which rockets off in front of us with a wide arc into the space of the field, a forest of wild carrot and dock. The magic has begun.

These are shooting woods, all ferns, nettles and wind-felled trees, with rides cut through the flora for beating the birds up into the sky. But their perimeters are dug with ditches, to keep the larger fauna in, and every now and then you come across wide wooden ladders with seats at the top, a plinth for a better shot at a deer. The dog knows these woods better than I do, and when he’s crossed the ditch into the green light of the woods, he pauses, sits, turns his nose up to the trees, and inhales their atmosphere.

Simultaneously, I ponder where to go. These woods roll out for miles, broken by fields whose corners I have sketched many times before. If we head due south, there’s the deserted chapel and walled garden, while, if we bear west, there’s that deer seat in the lightning-cracked oak that I still haven’t sketched. And then, right on the limits of my mind map, there are those long lines of coppiced hazel, whose ground is netted with honeysuckle. Every now and then you can find a hazel pole that has been strangled by the creep of these honeysuckles, twining around the branch, spiralling to the light. After several years, the honeysuckle is so tight that the girth of the pole spills out over its bonds, a muffin top of wood that corkscrews up the length of the pole. If you find such a specimen, and the stick either side of it is long and relatively straight, you’ve just found a walking stick worth about seventy quid in a country show. Cut it down, unfurl the honeysuckle, and you have a wizard’s staff that can be taken home, straightened with a damp cloth and paint stripper, capped and varnished.

But that’s a three-hour walk, minimum, and the sky is still specking with rain. We’ll stick to these woods. We’ll follow tyre tracks between the ditches of the wood and the perimeter of the fields. We’ll trace a circle around these woods and then cut through the tall nettles of a ride, back to where we are now. We’ll take in the badgers’ sett, and then that doleful pond, wide and shallow, with a fallen tree that forms a bridge from its perimeter to thirty foot above its centre. You can sit there, high above the sticky water, with the dog whinging at the brim, and watch the hawks that nest in the large ash. The whine of mosquitoes and the low hum of hornets. A stillness that feels endless.

We head west, through a gateway of two oaks that lean towards each other. This pair were saplings when the last great wave of vagrants had flooded England, the survivors of the Napoleonic Wars. In Discipline and Punish, Foucault wrote about their French counterparts who had experienced a hostile reception in France, and how they were viewed through the lens of the judiciary system: ‘the myth of a barbaric, immoral and outlaw class … haunted the discourse of legislators, philanthropists and investigators into working class life.’

To find a tree in Suffolk that is as old as this myth, you will have to trespass. Most of England’s grandest trees can only be found on private estates, saved from the saws of the Royal Navy by virtue of their aesthetic value to the recently enclosed deer parks. The closest to me is possibly the oldest of them all: the Thurston Oak.

It was the East Anglian Daily Times that alerted me to its existence. The article begins: ‘MIGHTY oaks from little acorns grow – and this tree has certainly lived up to the fourteenth-century proverb! With a girth so big it would take seven grown men to hug round its massive frame, it can lay claim to being the biggest recorded living tree in East Anglia.’

It was identified by a ‘volunteer verifier’ a decade ago, as part of the Ancient Tree Hunt, a scheme initiated by the Woodland Trust. You have to go and stand beneath this tree, touch its old gnarly bark, to see the true strength of a myth, how firmly it has rooted itself into the land.

Before this oak was seeded, England viewed its poor, destitute and homeless as useful tools for celestial self-improvement. The writings of St Francis taught that charity was next to godliness, and donations to poor relief helped you climb the ladder to heaven. When the Thurston Oak was a century old, the Black Death came to England and particularly affected the area of East Anglia, the front line of trade with the Continent. Between a third and a half of the population of England died, a tragedy on such a scale that it upended the order of Norman rule: the feudal ties that tethered peasants to the land they worked began to unravel, and, because there were so few labourers, workers were able to demand much higher pay. For the first time in the history of the working class, and maybe the only time, the poor had power – the power to choose to work and to travel to where conditions were better for them. This, of course, was deeply alarming for the hierarchy and required swift action: only a year after the outbreak of plague Edward III enacted the Ordinance of Labourers, which sought to cap wage increases and curb this new-found mobility. With its extra stipulation that any beggar who was deemed able to work should be refused charity, it is also the first time in English law that we see the distinction between the deserving and undeserving poor, a pathological obsession of the English that lasts to this day.

In 1388, the Statute of Cambridge placed yet more restrictions on the movement of people, both labourers and beggars alike – it prohibited anyone from leaving the district where they were living, unless they had a written testimonial issued by the Justices of the Peace for the area – an early passport for internal migration. For this, they had to prove ‘reasonable cause’, which was an official-sounding euphemism for the whim of the Justices. There was a central paradox to these new regulations that seems like an early, medieval draft of Catch-22: if you owned land, you could move; if you were landless, you had to stay where you were, where, without a master, you weren’t allowed to be.

The law applied to a broad church of people: itinerant labourers, tinkers, pedlars, unlicensed healers, craftsmen, entertainers, prostitutes, soldiers and mariners. They were freelancers whose jobs did not require them to be tethered to one place or another. They were called ‘masterless men’, and they roamed as lone wolves or packs of wild dogs, haunting the countryside, towns and minds of their betters. The most significant aspect to these various laws was that they criminalised nothing specific. Vagrancy was vague – it sought to criminalise not anti-social actions but, rather, a state of being, a social and economic status, a type of person.

In the corner of a field I see one of the larger oaks has come crashing down. On the ground beneath it are piles of soggy sawdust, evidence that some of the branches and thinner boughs have been cleared, but most of the tree remains, crushed against the earth and blocking our route. The dog leaps through its broken boughs and I follow awkwardly, untangling the leash, climbing through a canopy that has previously, all the while I’ve known it, been high above my head. The ragged mess of its trunk has been carved flat by chainsaws and sits like a kitchen table, almost two metres in diameter. According to the Woodland Trust, who have a handy matrix linking the diameter of a tree to its age, this tree was seeded in the late Tudor period, when paranoia about mobility stepped up a gear.

In the sixteenth century, the population of England almost doubled, rising from 2.3 million in 1521 to 3.9 million in 1591. According to The Land magazine, an infrequent periodical about local and global land rights issues, ‘by the mid-1500s, anything up to one-third of the population of England were living in poverty as homeless nomads on the fringes of an increasingly bourgeois society, in which they had no part’.

The rampant, unchecked enclosure of land had inevitably led to vast numbers of people being robbed of their homes and natural resources that now lay within the fences of the new lords of the manor. When the communities were cleared, they had to go somewhere, so they took to the roads. In a number of vagrancy acts passed in the mid-1500s, the punishments for people found out of their hometowns, whether unemployed, begging or just simply walking, ranged from three days in the stocks, to a branding of the letter S for Slave on the forehead or a V for Vagabond on the chest. You could be tied to a cart and whipped, you could have a hole of an inch diameter bored into the cartilage of your ear, and, if you were caught twice, you could face execution.

This emphasis on the persecution of the body tells us something about the Tudor perspective on vagrancy: it was the outward expression of an inner failing. People wandered and roamed the country because they had strayed from the path of righteousness – and this path was no longer mapped just by God, but by the state as well. To John Gore, writing in the early 1600s, vagrants were ‘children of Belial, without God, without magistrate, without minister’. But playwright Robert Greene, writing in 1591, expressed an even deeper Tudor obsession with the body: ‘these coney-catchers [rabbit hunters] … putrefy with their infections this flourishing state of England.’ As the moral failings of these vagrants had infected their bodies, causing them to act out of line, so too the vagrants infected the body politic of the land, threatening the health of the state itself.

The Tudor era was notable for intense civil unrest, with Kett’s Rebellion and the Pilgrimage of Grace being two of the larger rebellions and riots that occurred throughout the period. Having already enclosed a vast number of disparate people within the same legal definition, the Tudors began to talk of vagrants as an organised collective of seditious intent, a corporation working directly against the state. A popular legend of the day told how beggars and wanderers would meet annually at the Gloucester Fair to vote in new officials – a leader and an entourage of commanders and officers. Elizabethan dramatist Thomas Dekker wrote that a new recruit to this band of brigands had to ‘learn the orders of our house’ and to recognise there are ‘degrees of superiority and inferiority in our society’. The mythical Cock Lorel was one such leader of this tribe of dissolutes, his name meaning literally Leader Vagabond. He was credited with creating the Twenty-Five Orders of Knaves and meeting with a famous gypsy leader in a cave in Derbyshire, on the Devil’s Arse Peak, where the two of them supposedly sat down and devised an entire language that was to be rolled out across the vagabond community, called ‘Thieves’ Cant’. Jenkin Cowdiddle, Puff Dick, Bluebeard and Kit Callot were the men and women who led this army of vagabonds; but, again, there is no evidence that they existed anywhere but in the plays, books and fertile imaginations of the Tudor dramatists.

But these romanticised imaginings had a real effect. Government officials were paid by the head to round up vagrants and enclose them within ‘houses of reform’; since idleness was at the core of their withering souls, they would be forced to work for their moral improvement. When this didn’t work, they were shipped abroad, transported to the colonies of Virginia and the Caribbean to work as feudal serfs, tied to the farmsteads that would eventually drop all pretence of moral improvement for the cheaper alternative: African slaves.

But just as this bad blood was being piped out of the body politic, it was free movement on a global level that transfused another threat into the health of the land: the gypsies. In 1531 Henry VIII passed the Egyptian Act, whose very title expressed how misconstrued its statutes were. It described:

an outlandish people, calling themselves Egyptians, using no craft nor feat of merchandise, who have come into this realm, and gone from shire to shire, and place to place, in great company; and used great subtlety and crafty means to deceive the people – bearing them in hand that they, by palmistry, could tell men’s and women’s fortunes; and so, many times, by craft and subtlety, have deceived the people for their money; and also have committed many heinous felonies and robberies, to the great hurt and deceit of the people that they have come among.

This group of migrants had in fact originated in the Punjab region of northern India, a nomadic people called Roma who had entered Eastern Europe between the eighth and tenth centuries. They were accused of bewitching the English – their sleight-of-hand magic and their palm-reading fed into darker tales of blood drinking in Eastern Europe, werewolf mythology and that recurring nightmare of the wolf at your door. The notion of the glamour of the open road is itself sourced from the Romani word glamouyre, which was a spell the gypsies cast to free you of your hard-earned money and allow them access to your land.

Henry VIII’s phrase ‘calling themselves Egyptians’ speaks volumes about the mechanism of state projection – they were defined not by themselves or their actions, but by a panic that drew on the myth of barbarism, the fear of outsiders; by popular repetition, Egyptians was shortened to gypcyons which became gypsies, and a new scapegoat was born. Unlike the native vagabonds of the past centuries, the Roma people did not need to be branded with letters that marked their depravity – the colour of their skin was enough. And in a typical tactic of state propaganda, the myth of the gypsy was used to seduce the population into supporting legislation that restricted their own freedoms. In 1554, having just executed her sixteen-year-old half-sister Jane, Queen Mary passed another Egyptians Act which sought to legislate against this tribe of people plying their ‘devilish and naughty practices’. The statute forbade any further Roma people from entering the land and gave those already living in England sixteen days to leave. If they did not, and they were discovered, they would be hanged. Any possessions they had were to be divided between the state and the arresting officer, effectively co-opting people into paid vigilantism. However, in a detail that expresses the real root of the fear, the legislation allowed for them to escape prosecution as long as they abandoned their nomadic lifestyle or, as the Act put it, their ‘naughty, idle and ungodly life and company’. It was not their race, origin or palm-reading that upset the order of the state, it was their mobility.

Because geographic mobility was social mobility, or at least the slightest chance of it. During feudal times the working class were linked to the land in the same way as they were tied to their lord. To move away from the land was to move out of the lord’s jurisdiction, and, without any tied contract, it was to move out of any jurisdiction at all. The lords of the land were the lords of the law, and the lines of their property were the limits of their jurisdiction. By moving through the land, these men and women had snapped the leash that bound them to their masters. But there is another element to the perception of vagabonds that is impossible to ignore. It emerges not from the law books, but from the literature and folklore, or, in Freudian terms, not from the superego, but from the id: the eroticism of the gypsy.

D. H. Lawrence loved it. Emily Brontë loved it. It’s the oldest trick in the book of Orientalism, to demonise a group while simultaneously wanting to shag them. That way, when you do, it’s their fault and not yours: the Devil has had his way with you. And it goes back long before swarthy Heathcliff ever traipsed across the Yorkshire moors, to what is perhaps the oldest folk song in the English tradition. Sung by the Carter family, Woody Guthrie, Bob Dylan, the White Stripes, Planxty, Lankum and hundreds more, under the various titles of Raggle Taggle Gypsy, Seven Yellow Gypsies, Gypsy Davy, Gypsie Laddie, its legend is alive to this day.

Three gypsies cam’ tae oor ha’ door,

An’ O! but they sang bonnie, O,

They sang sae sweet and sae complete,

That they stole the heart of a lady, O.

It is said to have been written about a real gypsy by the name of Johnnie Faa, who in 1540 has been declared King of the Gypsies by James V of Scotland. As the story goes, he ran off with the Countess of Cassillis, who lived on the coast with her earl forty miles south of Glasgow. The earl comes home to find his property has been stolen and he gallops off to reclaim her; he catches up with Johnnie, his wife and the band of gypsies, singing songs around a fire. He imprisons his wife for the rest of her life, hangs the men in front of her window and, insult to injury, carves their faces into its mullions. That the story is most likely untrue did not stop the ballad spreading across England, with slightly different details and with several different endings. In all the versions, the lady is charmed away by the gypsies, bewitched by their glamour, and forsakes her comfy feather bed and expensive leather shoes for a rough life on the road.

The lady she cam doon the stair

And her twa maidens cam’ wi’ her, O;

But when they spied her weel’ faured face,

They cuist the glaumourye o’er her, O.

This song is about the glamour of the open road, and is a working-class hymn where the rich don’t always come out on top. But it can also be read as a metaphor for land seizure. At the start of the seventeenth century, during the continued enclosure of England and a new colonial imperative that was seizing land outside of the country, the improvement of wild land and the taming of wild women were concepts in constant conflation. One was a metaphor for the other. On his return from Guiana, Sir Walter Raleigh described it as ‘a country that hath yet her maidenhead’, meaning that it had never before been penetrated and mastered by any man. Conversely, the crime of rape was not created to protect women from violence but to protect men from a violation of their property rights. In 1707, Lord Chief Justice John Holt described the act of a man who had had sex with the wife of another as ‘the highest invasion of property’, referring, of course, to the man’s property of his wife, and not the woman’s property of her own body. Once a man had claimed dominion of his property, and fenced it with marriage, it was his right to enter, and his alone – it, or she, became impregnable.

In the Tudor era the cult of exclusion was so strong that it entered the psyche and acquired a Freudian fetishisation that had all the power and licentiousness of a sexual taboo. The gypsies, feral, wild and earthy, with their slippery attitude to the boundaries of possession, represented the abomination of this property concept, and were evoked as sexual predators, a threat to the family and state alike. And this interplay between land and sexual taboo, between violation and domination, continues to this day, in the parable of Nicholas Van Hoogstraten.

Hoogstraten has been called many things: slum landlord, the sad Citizen Kane of Sussex and, by one of the many judges he has faced, ‘a self-styled emissary of Beelzebub’. He is a B-movie villain, a character whose life story might have been written by Martin Amis in a pique of misanthropy, in a story so far-fetched it could never be published. Early on in his career he spent four years in jail for throwing a live hand grenade at a Jewish cantor and, in 2002, was sentenced to ten years for the manslaughter, or alleged assassination, of Mohammed Raja, another landlord tycoon. He made his money Rachman-style, by buying houses full of sitting tenants and then using a variety of bully-boy tactics to evict them. When they were alive, he referred to his tenants as ‘scumbags’, ‘dog’s meat’ and ‘filth’ and when five died in a fire in one of his apartments in Hove, he described them afterwards as ‘Lowlife. Drug dealers, drug takers and queers. Scum.’

He is currently in the process of building an enormous palace in Uckfield, East Sussex, started in the 1980s and still unfinished, with rocketing costs estimated at £40 million. To claim the land, he evicted a care home of elderly residents. Built both to emulate and to dwarf Buckingham Palace, it has two gleaming copper domes, covers the entire width of his land and, entirely imprisoned in rusting scaffolding, it is the architectural equivalent of Doug Bradley’s character in the Hellraiser films.

I went to visit the estate with two friends: a bike ride, sandwiches in the pub, early summer, a lovely day out. We cut into the estate on a public Right of Way, and then hopped the barbed wire fence into an Eden of nature. Like modern-day Hiroshima, the almost absolute absence of humans has allowed Mother Earth to thrive in peace: it is a George Monbiot wet dream, entirely rewilded. For an hour or so, I sat in the chest-high grass and drew the house. A fox walked by me, entirely unfazed by my presence and close enough for me to stroke its gorgeous fur. Butterflies bounced low over the earth, insects hummed in the air, I got tan lines.

But, twenty years before, this place was the scene of a real-life pantomime drama, between the Ogre of Uckfield and the rosy-cheeked pastoralists of the Hobbit Activity Guild, otherwise known as the Ramblers’ Association. The Right of Way we had taken is labelled on the maps as Framfield Number 9. It is a path that has been featured on maps for 200 years or more, the route villagers took to church every Sunday. Hoogstraten reacted so badly to the sporadic invasion of walkers still using this footpath that he secured his property against the common law rights of the locals by erecting a barn over it and blocking the entrance with a corrugated iron sheet, discarded masonry and a host of refrigeration units. When the Ramblers staged a demonstration outside the obstruction, he went on the BBC to label them ‘the scum of the earth’.

In 1999, the Ramblers’ president Andrew Bennet MP led a walk along the path and the following day a six-stranded barbed wire fence was erected where the path meets the road. When the ramblers launched a case against Hoogstraten, it was delayed because he had changed the ownership of the land from his name to a shadow identity, a corporation named Rarebargain Ltd. But, with a new Rights of Way Act being discussed at that time in Parliament, the Ramblers were determined to make this case as public as possible: they wanted to highlight the realpolitik of England’s Rights of Way network, of which they estimated a quarter was blocked by landowners.

Hoogstraten was incandescent. ‘Let them waste their time and money,’ he told reporters. ‘I’m not going to open up the footpath. Would you have a lot of Herberts in your garden?’ Unaccustomed to 1980s slang, or Landlords’ Cant, I had to look up ‘Herberts’ – a Herbert is a creep who befriends your wife so that he can shag her at a later date. He is the incubus of patriarchal possession, an invader of conjugal property. In a later interview with the Guardian, Hoogstraten modified this statement saying, ‘Herberts wasn’t actually my word, it was one of the builder’s … I said perverts, the dirty mac brigade.’ Perverts or Herberts, the sexual connotations Hoogstraten has with his land are clear – he owns the land like he owns his bitches (his often-repeated term for his several wives) and any penetration is a direct threat to his dominion, his manhood, a perversion of property law.

The woods around me are a scene of devastation. The foresters have been harvesting them, but have not yet tidied them into stacks, so their long poles lie scattered, strewn like pick-up sticks, as though a dinosaur has swept its tail and felled them by mistake. Their cut ends are bright sticky circles of orange and the air is scented with their sap. I follow the tyre track, picking my way carefully through a mat of crushed branches until I come to the badger sett and sit on a trunk in the vain hope of seeing one: but try as you might, you can’t coax the magic.

The dog is tracing scent, head bowed to the ground, drawn by his nose. We’re back to where we started, in the young woods planted by the 3rd Lord Henniker when he took over the property in 1821. The Napoleonic Wars had ended, and with it the mass conscription that had dragged so many young men from England. They were back now, wounded, mutilated, unemployed and hungry, regurgitated into a state that had no place for them. They ranged the land, slept in coppices and spilled down the highways, a new cast of characters in the old myth of the deviant wanderer. A new Vagrancy Act was quickly written and passed by the cartel of aristocratic landowners otherwise known as Parliament, to clear them off the land into prison. Its effect was to outlaw homelessness, and it is still in use today. In 2014, three men were arrested and charged under Section 4 of the 1824 Vagrancy Act for taking food that had been thrown away into skips outside an Iceland supermarket in north London. A year later, sixty-two homeless people were arrested in Sussex under the same act, rounded up by plainclothes police officers who walked up and down the seafront, waiting to be asked for a quid.

The Act stipulates that ‘every person wandering abroad and lodging in any barn or outhouse, or in any deserted or unoccupied building, or in the open air, or under a tent, or in any cart or wagon … shall be deemed a rogue and vagabond’ and later, in provision five: ‘an incorrigible rogue’. The sentiment of the Act is as arcane as its language. Even in its day, William Wilberforce objected to it on the grounds that it did not take into consideration the many reasons which might lead to homelessness; again, it was not punishing any particular crime but, rather, the symptom of a social problem. The Act was amended on a number of occasions, making the definition of vagrancy only more vague. In 1838, its scope was widened to include the publication of material deemed to be obscene, reinforcing that notion that vagrancy was a catch-all term for both geographic and moral deviance. In 1898, a further amendment sought to clamp down on street-walking, or prostitution, but was in practice used to imprison homosexual men for their deviant sexuality. Again, it was a law that criminalised not an act, but a type of person.

In 2018 a delegation of thirty Tory backbenchers signed a letter calling for the criminalisation of trespass, a pledge that had already been mooted in their manifesto of 2010. The letter followed the anger of the locals of Thames Ditton in Surrey, when the police refused to evict a gypsy camp from some local common land. There had been reports of tricycles stolen from playgrounds and instances of shoplifting – criminal acts by individuals with a justified legal response. But the locals wanted the whole site cleared, to get rid of the lot of them. When the local Elmbridge police force tweeted, reasonably enough, that they could not make arrests without evidence of wrongdoing, Karen Randolph, a councillor who represented the area said, ‘We are all incandescent with rage because of that tweet.’ When the site was eventually evicted by the council, the Daily Telegraph reported: ‘The council also hired a specialist cleaning company to carry out a “cleanse” of the park’s playground following their stay.’

‘Cleansed’ is a potent word, and with respect to gypsies, a little too apposite. In 1927 the 400 or so gypsies camping in Nevi Wesh, the Romani term for the New Forest, were rounded up and herded into seven compounds. Fenced in from their mobile life, they were simultaneously forbidden from building permanent structures and issued with six-month licences for their stay, which could be revoked if their behaviour upset the Forestry Commission.

The gypsies had been living in the Nevi Wesh for centuries, and in the nineteenth century would return each year from harvesting hops in Kent to spend the winter there. The 1920s had seen a surge of incomers into the New Forest area, including Arthur Cecil, the brother of the prime minister, who wrote in his report to the House of Commons Select Committee: ‘They are a great nuisance to everybody.’ Another local resident was the artist Augustus John, who lived in Fryern Court on the outskirts of the forest, who said later: ‘although nobody so far has proposed to liquidate these nomads after the Hitler style, is it possible that, in his own country, John Bunyan’s people have been sentenced to a lingering death?’ These incendiary words were echoed by an altogether more sober authority, the Centre for Holocaust and Genocide Studies, who said after the war: ‘It is hard to believe that civilised Britons would herd innocent people into compounds because of their race, just as Nazi Germans would a few decades later.’

But it wasn’t just their race. Today there are around 300,000 people in the UK who identify as Gypsy, Roma or Traveller. In Europe they number over twelve million and are recognised as the largest ethnic minority in the EU. This statistic alone is indicative of the persistent obsession that rooted society has with gypsies: ethnicity is defined by the UN Office of National Statistics as a concept that ‘combines nationality, citizenship, race, colour, language, religion, and customs of dress or eating’ – yet not one of these signifiers embraces the entirety of this group. Instead, it is the association and history that these people have with travel that has grouped them out to the margins of society: mobility as ethnicity.

Fixity is the orthodoxy of the modern European age, and the trouble with travellers is that at some point in time, at some point in space, they will lay their camp. Within the tight lines of Tudor property law, there was no room for that and today you are only allowed to stop for forty-eight hours in special council-allocated sites, tarmacked and fenced enclosures with all the romance of a disused motorway service station. Property simply cannot comprehend mobility. Perhaps the glamour of the open road is just another misappropriation by the authorities that defined them. Perhaps the glamour cast by the gypsies is not in fact a spell, but its direct opposite – a jinxing of the spell of private property.

The storm isn’t breaking. It might even pass us by. The air is tense with it, but the drizzle is thinning. The sun is pushing through the cloud and the horizon is greasy with light. Me and the dog are picking our way through a tight thicket of thistle and nettles, following the long disused pheasant ride that cuts right through this small section of wood. Either side, dripping trees. Directly in front of us, the light has smeared through the dark clouds, flaring off the thistledown, glaring from the wet leaves. Everything glistens. There is an arc of not one but two rainbows, perfectly placed at the end of the ride, and the scene is so beautiful it’s naff, the closing credits of a Disney film. I breathe it in. The dog, not known for his patience, has become inured to this kind of artsy pause, and is now resigned to the dragging moment. He hunkers down onto the ground and rests like a sphinx, drinking in the air with his nose. There is a cracking from the trees, and I glance. It takes me a second to see the dark forms of deer passing, almost silently, through the poles of the wood. The dog is casual, unengaged. I don’t move. The deer are heading towards us, a line of maybe ten, about to slip out into our ride. When the first one appears, tentative, it is heavy headed, almost goat-like, pagan. These are not the pretty things I was expecting: they are not roe deer, but red deer, and I’ve never been this close. A second follows, head, then hoof poised for a long time before it places it and raises the next. They are more than cautious, but the scene is about to explode. Quietly, I let the cord of the dog’s leash retract into its canister, and click it locked. The dog and his miraculous sense of smell have failed to register a line of deer directly in front of him, but instinct is about to take over. A third deer is out, this is a convoy, picking its way as a team through the woods. And then, quickly, it happens. The dog’s ears prick, his head turns and he bullets off his haunches, yanking my arm taut, yearning against his collar, front paws paddling the air, held back by my weight. The deer swing like wooden puppets on a string and stream seamlessly away through the trunks. The last to turn are two stags, half glimpsed, who trot indignantly after the herd.

This kind of moment is only available off the path. It is an accident, unwilled and unplanned, but it comes dressed as poetry. It is prosaic, but it feels like a miracle, it feels meaningful, and it leaves me with my heart thumping in my throat. The deer were so close they felt dangerous; not aggressive, but wild-eyed and unpredictable. I would swap a hundred nice walks along a pretty Right of Way for this one moment of magic.

And now the heavens have opened. The dog, so focussed a moment ago, appears to have entirely forgotten the incident and is sniffing nonchalantly at my heels. I release the catch on his leash, give him some slack, and together we turn, retrace our steps through the waterlogged field and end up on the path back home.

Behind me, to the south, the Right of Way continues through woodland to a thatched-roof church, whose back door is always open. St Mary’s Church of Thornham Parva was built about a century after the Norman invasion and is a tiny treasure trove of history. It’s odd to be able to walk into a museum piece, with no red ropes or blue blazers prohibiting your action. In truth, the 800-year-old painted altarpiece is set behind alarmed glass but it’s nice to be trusted not to squirt bleach at the half-faded and even older murals that adorn the nave. Perhaps there are no vandals in this part of Suffolk, perhaps the gesture itself inspires a custodial reverence, perhaps the murals are so mashed up it doesn’t feel like there is much to desecrate. But you can just about make out their subject: St Edmund, fleeing on horseback from the Great Heathen Army, the Vikings that ravaged East Anglia in the late ninth century. Next wall, he doesn’t make it, but someone has redacted the holy martyrdom by installing a window in its place. This is regrettable, because Edmund was tied to a tree, beaten with iron bars, shot with arrows and beheaded, which is a great gig for a Christian artist of any era. The final scene shows Edmund’s remains, carried to his shrine in Bury St Edmunds. The path I am walking formed part of that journey, a network of highways that once linked Hoxne with Bury, some twenty-five miles apart. This particular section of the route is called Cowpasture Lane, and it is a superstar path, a literary A-lister.

The lane is described by writer Richard Mabey as ‘an aboriginal droveway cut and trod out though wildwood, which survived in marginal strips after the wood beyond had been cleared for agriculture’. He estimates that it was first hewn out of Iron Age forests, making it older than any of the commons or settlements of the area. Roger Deakin also refers to this path in both Wildwood and his collection of diary entries, Notes from Walnut Tree Farm, claiming it was a trade route leading on to three neighbouring markets.

This part of it, south of the railway line, is almost 100-foot wide in some places. It was then not just a footpath but a highway for various lanes of traffic, wagons, horses, cows, and also offered enough room for the cattle to pasture. The iron shoes dug up along its route point to the fact that these animals were being driven on long journeys (as cattle were only shod for distance) and so would have needed a place to huddle overnight. As Deakin puts it in a letter to the Mid Suffolk council: ‘the idea of classifying Cowpasture Lane as a footpath instead of a byway is almost as absurd as the idea that the M11 might one day in the future be accidentally classified as a footpath on a map in the year 3003. I exaggerate of course, but you will appreciate my point.’

It was a busy route. So much so that, if Mabey is to be believed, it didn’t just link places, it created them. And the strength of its use determined its longevity. From Thornham all the way to Mellis Common, with the one curious exception of the vast field along the railway line, Cowpasture Lane is an unbroken tunnel of green, with thirteen species of tree that are descendants from the ancient wood now almost entirely obliterated from England. It is another museum piece, entirely unroped. When the path was first forged, it was a refuge through the wilderness, and today, stark against the blank agriculture of Suffolk, it is a refuge for it.

I step out into that open field again, and, at the opposite end, I see the train banshee by. Through the blurred lens of falling water, I wonder if I’m seen. The rain is heavy now, a roar, and even the dog has lost heart. We cross the field, cross the line, and follow the lane until it opens out onto the common. It is like stepping out into a storm-swept beach, the sea of long grass combed into waves by the wind. The trees sway like river reeds and I turn right, and right again, up the track to Walnut Tree Farm, once the home of Roger Deakin.

I came here originally as a pilgrim from his first two books Waterlog and Wildwood. A mutual friend made the introductions to the current owners of the house and I returned later on in the year, with the words of my first book half written, to live in my imagination for a couple of weeks, bashing away at my book while cats curled around my legs. A year or so later I was introduced to their gorgeous and priapic Rhodesian Ridgeback puppy, and returned intermittently to dog-sit while the family were away on holiday.

I enter the kitchen with trousers clung heavy around my legs. I am drenched. I feed the dog his stinking meatmush, strip naked and pull on some tracksuit bottoms. I take an old towel from the Aga and rub him down as he hofs back his food. I eat and then, barefoot, walk with him out into the rain to the second paddock, where the shepherd’s hut stands. I snap some ash twigs from a neighbouring tree, find the key and enter. Shivering, I kneel at the woodstove by the door, and load it up. Little cylinders of wood, branches chopped on the bandsaw, the ash twigs, and some strips from a GCSE exercise book: There are four main reasons for Macbeth’s shame goes up in smoke, the lid goes on and the stove catches and breathes deeply on the pipe, which starts to ping as it heats up.

The rain is rattling on the corrugated roof, the fire is crackling, the dog has settled in for the long haul and is snoozing on the bed. I hoist a stack of old folders from the floor to the desk by the stove and begin leafing through the papers. Aerial photos of the land, crinkly typewritten letters, photocopies of newspaper clippings, long council reports; these yellowed papers detail the forty-year struggle to save Cowpasture Lane from closure. From Roger’s initial letters to the council in the early 1980s, the first volley of gunshots in a battle against a local farmer, to the affidavits, the written testimonies and the newspaper accounts of the showdown at the railway line, the stack is a loose-leaved codex on the war between private and public rights.

For starters, there’s the story behind the gap in the woodland tunnel that runs from the railway line across the open field. In 1971, the farmer felled the corridor of trees and grubbed out their roots, levelling two fields into one, so that his plough could move in one unbroken line. He also took down a line of trees heading west from the woodland and you can still see their footprints today, from the satellite image on Google Maps, a pale scar tissue on blank, ploughed earth. It was only through an affidavit from Roger that he had to pay a fine for this vandalism. Then, at the start of 1980, there are letters from other residents to the council arguing that, no shit, the farmer hadn’t marked the Right of Way through his new unified field, as was his duty, and after ten months he is ordered to wheel-mark this public passage, Path Number 7 as the paperwork calls it, through his sugar beet.

But the battle was only just beginning. Cowpasture Lane divided Roger’s paddocks on the east and one of the farmer’s fields on the west; a line in the sand. Somehow, and these are the facts that slip through such papers, Roger caught wind that the farmer was planning to uproot the trees along his side of the lane, and to plough up the lane itself, which covers about 1.6 acres of land, converting an ancient right of passage into an extra 500 quid of annual private profit. So Roger forms a supergroup, a Traveling Wilburys of literary and scholarly eminence, who bombard Mid Suffolk council with botanical, historical, archaeological and ecological evidence. Representatives from Friends of the Earth, Open Spaces Society and the Ramblers’ Association add their letters to the bombardment, alongside big guns like Oliver Rackham, Richard Mabey and the grandest literary howitzer of them all, Ronald Blythe. BOOM, BANG, CRASH, they get their Tree Preservation Order from the council, and the line of trees along the lane is saved, protected by order of the secretary of state.

But wait: the order is given on the Friday, to come into effect on the following Monday morning. The local paper reports the victory that weekend, the farmer reads it and early Monday morning he’s on the lane, with some men and chainsaws. This is where the purple prose of the local newspaper takes over: ‘Nightingales no longer nest in Cowpasture Lane. Their song has been silenced by the screech of chainsaws and the hacking bill hooks. A Passchendaele silence reigns … no birds sing.’ Roger’s account is more measured: ‘On the Monday morning their work was hampered by the presence of myself in the company of reporters and photographers from the Diss Express and East Anglian Daily Times until the Mid Suffolk district council’s landscape officer … arrived, breathless, at lunchtime, with the TPO.’

What a strange, tense moment that must have been. Hampered: how in hell do you ‘hamper’ men with chainsaws and billhooks? The presence of a photographer or two must have given Roger some courage, some hope that he wasn’t about to have his legs sawn off, but to hold the fort until late morning, when the bureaucratic cavalry came huffing up the path, was a sturdy feat. Mellis is a tiny village, and all the men would have almost certainly known each other. In this isolated spot of the railway crossing, the politics of neighbours conflated with the historical conflict of public and private property.

Over the course of the last fifty years, Mellis has lost 50 per cent of its hedgerows. On the land owned by this one particular farmer, only 7 per cent of his original hedgerow remains. When the men stopped work, they had already cut down a large section of the 300-yard path, with the intent of completing their job right up to the common and then filling in the ditch. Many of the trees were now stumps, flat-top stools, their trunks and branches lying devastated on the earth. But because of an obscure ruling from 1978, the Tree Protection Order given by the council still applied. In 1978, a small woodland in Kent was razed by a farmer. In Mabey’s words: ‘The forest came to be known by locals as the Horizontal wood, and now, protected by the Kent Wildlife Trust, it is thriving. The precedent had been set, and the stumps were preserved. Today, there is no evidence whatsoever of damage, the hazel and the ash have sprung back.’

The life of a wood, as with the path that runs through it, is in its roots. Cowpasture Lane was saved.

It’s dark now, the rain is gentle; I stack up the papers and cross the paddock with the dog, past the moat, to the house. I put some leftovers in the bottom tray of the Aga, and go to squat by the enormous Tudor fireplace in the living room, splitting a log into splints for kindling. This time it’s maths homework that starts the fire. I pull down Roger’s three books from the shelf and settle before the hearth.

I look up an early scene in Waterlog: Roger has traced a paragraph from William Cobbett, the Georgian pamphleteer, to Winchester, where the boys’ school meets the water meadows. He has been swimming in a reverie of wild watercress and natural springs, thought-streams of the past eddying into the present moment. Out on the shore, his head is swirling with Cobbett’s imagery, of fresh cream and milkmaids, and the prose is getting distinctly horny when he is interrupted by two authoritative figures, one ‘strawberry-pink with ire’: ‘You do realise this is private property?’ Roger is about to scarper, and save everyone the bother, but he remembers Cobbett and his account of the two poachers hanged in Winchester in 1822, whose crime ‘amounted to little more than I had just done’. So, tongue in cheek, he stands his ground: ‘I got changed as languidly as possible, then casually leapfrogged the fence and sauntered off along the path, whistling softly to myself, as an Englishman is entitled to do. Excuse me, came a voice, does that fence mean anything to you?’

It’s a teacherly, paternalistic question; its sarcasm is rooted in a conviction that is utterly blinkered to any position other than its own. When Roger responds ‘sweetly’ with a watered-down Woody Guthrie sentiment (a sort of ‘this pond was made for you and me’), ‘the river keeper practically fell off his bike. The porter flushed a deeper strawberry.’ The scene is quaint, utterly devoid of violence, and reminiscent of English 1970s sitcom farces, featuring wily country sorts and stout-bellied authoritarians. Yet to Roger, whistling his Englishman’s entitlement, it is of national significance. It springboards into a discussion of the ‘Right to Roam’, the ideology that opens up certain land to walkers, irrespective of pathways. Roger was writing before the Countryside and Rights of Way (CRoW) Act of 2000, a major piece of legislation which legitimised off-path wandering on mountain, moor, heath, down and common land in England and Wales. That was 150 years of campaigning to gain what to this day amounts to only 8 per cent of the landscape. His words still apply: ‘I say “rights” to point up the paradox, that something that was once a natural right has been expropriated and turned into a commodity … the right to walk freely along river banks or to bathe in rivers, should be no more bought and sold than the right to walk up mountains or to swim in the sea.’

During the Middle Ages, paths formed organically through the practical needs to get from one place to another. As the new notion of private property erected fences to defend its position, new definitions of land brought with them new definitions of rights to them. But these pathways remained necessary for the functioning of the countryside and so were protected by the common law standard, ‘once a highway, always a highway’. When enclosure finally emptied the countryside of its workers, many of these paths became disused and most disappeared, churned by the plough, clogged with brambles or deliberately blocked by landowners.

When the Ramblers launched their case against Hoogstraten they succeeded by sheer will and canny politicking. Councillor Skinner of East Sussex council was blunt about the odds. ‘He does have an extremely good record in the courts, and English law tends to be biased towards people like him. We don’t stand a bloody chance.’ But eventually, because the evidence proved a long-standing Right of Way, they did win. Hoogstraten’s shadow company, Rarebargain Ltd, were fined £1,600 and ordered to pay the £3,500 costs of the Ramblers’ case. But somehow the costs were not paid, and the obstructions remained. Meanwhile, with Parliament discussing the CRoW Act, they petitioned hard for a clause to be added to the Act which would require, by law, such obstructions to be removed. Among ministers this clause became known as the Hoogstraten clause and eventually, when included, became Section 64 of the CRoW Act, defined as the ‘Power to order offender to remove obstruction’. The day after this section came into law, Kate Ashbrooke, the chair of the Ramblers’ Association, returned to the Framfield footpath and served notice to the estate. The case was heard two months later and Rarebargain, who did not appear in court, were fined £1,000 per obstruction, the barbed wire fence, the padlocked gate, the refrigeration units and the barn. From beginning to end, it took the council thirteen years and £100,000 in court costs to open up the path. In February 2003, Ashbrooke returned to the path with a gaggle of press and finished the job with a pair of bolt-cutters.

Today there are 117,800 miles of public footpath in England, half that of a hundred years ago. It was only in 1949, in the National Parks and Countryside Act, that procedures were introduced to legitimise these rights of way, to set them in stone. ‘Definitive Maps’ were drawn up for all counties in England, designating the Rights of Way, securing these passages under protection of the secretary of state, and from the 1970s they were marked on OS maps.

But while these definitive maps enshrine a public right, they simultaneously legitimise the space that is off limits, the private right. Every pathway that is secured by law further strengthens the fence between us and the land either side of it. The Right of Way Review Committee in England, which influenced the Land Access Acts of 1981, 1990 and 2000, was set up in 1979 by the Ramblers’ Association, the National Farmers’ Union and the Country Landowners’ Association, the latter two being dedicated to protecting the rights of landowners. The members of the CLA, just 36,000 of them, own 50 per cent of the rural land in England and Wales, a statistic lifted off their own website. The definition of public rights is in fact a euphemism for the protection of the rights of a very small proportion of the population. Our ‘rights’ to the land have become streamlined into thin strips of legitimacy, the freedom to toe the line.

Another line is fast approaching – a cut-off line. On 1 January 2026, because of the same Act that returned to us our mountains and moors, any path that has not been registered on these Definitive Maps will automatically be extinguished. To save Cowpasture Lane, just one path, from closure was a relentless struggle, involving at least six different battles over forty years (thirty of those before Roger), each requiring evidence from experts, photocopies of countless maps and aerial photos, an intimate knowledge of the small print of Rights of Way legislation, and, perhaps most importantly, the time and will to bother. To register a path before the cut-off date, there is a 316-page guide which, with all the exuberant charm of a chemistry textbook, will either help you, or break you. You must submit a Modification Order, hard copy, with enough evidence attached to it to support your claim. This evidence could include turnpike records, enclosure records, tithe maps, railway and canals plans, highways records, sales documents and Inland Revenue valuation maps, all of which must be photocopied by visiting the records office, national archive, parliamentary archives, or private records of a particular estate (almost impossible). You are entering a hellish world of box files, permission forms, waiting rooms and impenetrable legalese; it is a process that would, in Hollywood format, be relegated to a pulse-thumping montage, but in real life takes weeks, months and sometimes years. What’s more, of course, while every council and government official you meet is paid for their time, you will be a volunteer, unpaid, and must therefore engage all your efforts as an extracurricular activity, squeezed in between your other responsibilities.

And to what end? To secure ourselves a causeway of legitimacy while all around the land has been washed away into a sea of private ownership. The real question is why we allow ourselves to be fenced off in this way. Why do we obey the command of signs and the limits to our freedom silently scrawled across the land in lines of barbed wire? Where does this obedience come from? As Roger says of the interdicted military land of Orford Ness, ‘This makes me feel like a schoolboy and want to break bounds.’

The fire is guttering, causing the shadows of the room to lurch up and down the walls. The cigarette has burned itself down to a long cable of ash. Somewhere in the room there is a gloppy sound, wet and insistent, the sound of an old toothless man chewing on cold lasagne. The dog is licking his balls. He’s really churning away at them, lapping at them as if they were scoops of vanilla ice cream, entirely untroubled by my gaze. On the page in front of me, the past intersects with the present: just a mile further down the track from where I’m sitting, twenty years ago, Roger Deakin has climbed the fence of Burgate Wood. He has found a patch of land and laid down his head where a decade later his ashes would be scattered. In the light of the fire, his words are alive:

Sleeping one time in Burgate Wood on the moated island of the old hall, I put my cheek against the loam and the cool ground ivy. When I closed my eyes, I saw the iceberg depths of the woods root-world … this is the part of the wood that only reveals itself occasionally after a big storm, when the trees have keeled over and the roots are suddenly thrown upright, clutching earth and stones. How deep do roots go?