Wives, Witches, Spells and Protest

‘To spin the web and not be caught in it, to create the world, to create your own life, to rule your fate … to draw nets and not just straight lines, to be a maker as well as a cleaner, to be able to sing and not be silenced’

– Rebecca Solnit, Men Explain Things to Me

I shut the heavy door behind me and step into silence. I pad gently up the aisle, past tall pointed arches and rows of cold wooden pews, and pause at the chancel. In times past, this would have been my limit, the space beyond reserved for choir and clergy, but these days the church is open for tourists and the transgression has been diffused. I walk into the space before the altar, packed and stacked with the tombs of the dead lords of Rutland.

Frozen in stone, there are eagles and lions, peacocks, hunting dogs and unicorns. There are nameless attendant servants, smaller in size and status, on their knees in perpetual prayer. In this small space, there are eight earls and four dukes, with the bones of another fifty lesser family members interred beneath my feet. The men lie in state, some dressed in intricate Tudor ruffs, one in the clothes of a Roman general, another in medieval armour, and their wives lie beside them, faithful, pious and pure. Their lips are pursed and their hands clasped in prayer. All their eyes are open. The alabaster carvings are so delicate it seems like the thinnest veil of white silk has been laid across their faces, which with the slightest draught, might slip off and stir them from their daydream. I barely breathe.

Before me, laid out like corpses on a morgue table, are the life-size effigies of the 1st Earl and Countess of Rutland. Over the sixteen years of their marriage, Eleanor Paston was almost constantly pregnant, bearing the earl eleven children. But, because the first two were female, the couple had to wait for their third child until they had secured the lineage of their estate. By the rule of male primogeniture, their fortune skipped Anne and Gertrude, and landed with their first son, Henry.

The primacy of the first-born male was another of William the Conqueror’s imports. Its express aim was to protect the integrity of estates from being particularised into separate holdings, divided by their children; it was a legal wall around the concept of dynasty. The Bible had set the precedent for male inheritance, but Anglo-Saxon custom (as enshrined in the eleventh-century laws of Cnut) provided that the lord’s land ‘be very justly divided among his wife and children’. Before 1066, Anglo-Saxon women were autonomous individuals, who could own land, run businesses and sign legal contracts. When a marriage was agreed, it was the husband who paid a dowry, the morgengifu, though not to his wife’s father, but directly to her. As a couple, both man and wife handled the finances of the estate and, if they divorced, they halved the holdings between them. But when William imported the cult of exclusion into England, he brought with him another legal fiction: wives became property, too. Under Norman law, a married woman was termed ‘feme couvert’, a covered woman, and her land, her rights, her ‘very being’, were entirely subsumed under the protective wing of her husband. In Genesis, woman was created when the Lord took Adam’s rib; in Norman England, Adam was taking it back, plus interest. Writing in 1769, William Blackstone described couverture, which after 600 years was alive and well in Georgian England: ‘By marriage, the husband and wife are one person in law: that is, the very being or legal existence of the woman is suspended during the marriage, or at least is incorporated and consolidated into that of the husband: under whose wing, protection, and cover, she performs every thing.’

This, of course, was done for her own good. Blackstone continues: ‘Even the disabilities which the wife lies under (resulting from coverture) are for the most part intended for her protection and benefit. So great a favourite is the female sex of the laws of England.’

When Eleanor was married in 1523, her value was her womb. Her virginity was a commodity that was bartered to secure a land contract between two men, a guarantee of uncontested lineage. Her cervix was the tunnel that bridged two landed estates and her uterus was the garden in which the earl would plant his seed and cultivate his heir. Had Eleanor not died in 1551, had she lived to a biblical age, she would have had to wait another 319 years to possess her own property, when Parliament passed the Married Women’s Property Act, while under care of her husband, she could be raped by him, by law, all the way up to 1991.

As the wife was stifled in law, so there were strict social orthodoxies as to her countenance in public and private spheres. Gervase Markham summed it up in his influential book The English Hus-wife (1661): ‘Our English housewife must be … wise in discourse, but not frequent therein, sharp and quick of speech, but not bitter or talkative.’ If a wife flaunted her speech, if she got too saucy by half, she could be branked, that is, have her head encased in a scold’s bridle, an iron muzzle that masked her face, with a two-inch bridle extended into her mouth to suppress her tongue. For a wife to speak her mind was deemed inconsistent with her legal status, a trespass outside of the couvert placed upon her.

On the south wall of the church, lying parallel to Eleanor and her husband, is the tomb of the 6th Earl, perhaps the grandest of them all. He lies, with his two consecutive wives Frances and Elizabeth, beneath a barrel vault whose pillars and pediment run to the eaves of the church. Behind their heads, their daughter Katherine kneels in prayer, hands clasped, and at their feet are their two boys, frozen for ever in infancy, each carrying a small skull. The inscription at the back of the tomb explains that they ‘died in their infancy by wicked practises and sorcerye’. This is the only tomb in England to record death by magic: they were killed by witches.

Leaving the church is like waking up – the noise returns, the real world was there all along. My mind moves from male primogeniture to flapjacks and cheese pasties. I stock up for the night ahead, unlock my bike and head south to Belvoir Castle, the home of the bones in the church. Five miles south of Bottesford, Belvoir is still the principal seat of the Rutland lineage and the core of its 15,000-acre estate. The castle is open for tourists, and the 11th Duke lives in a private wing of the castle.

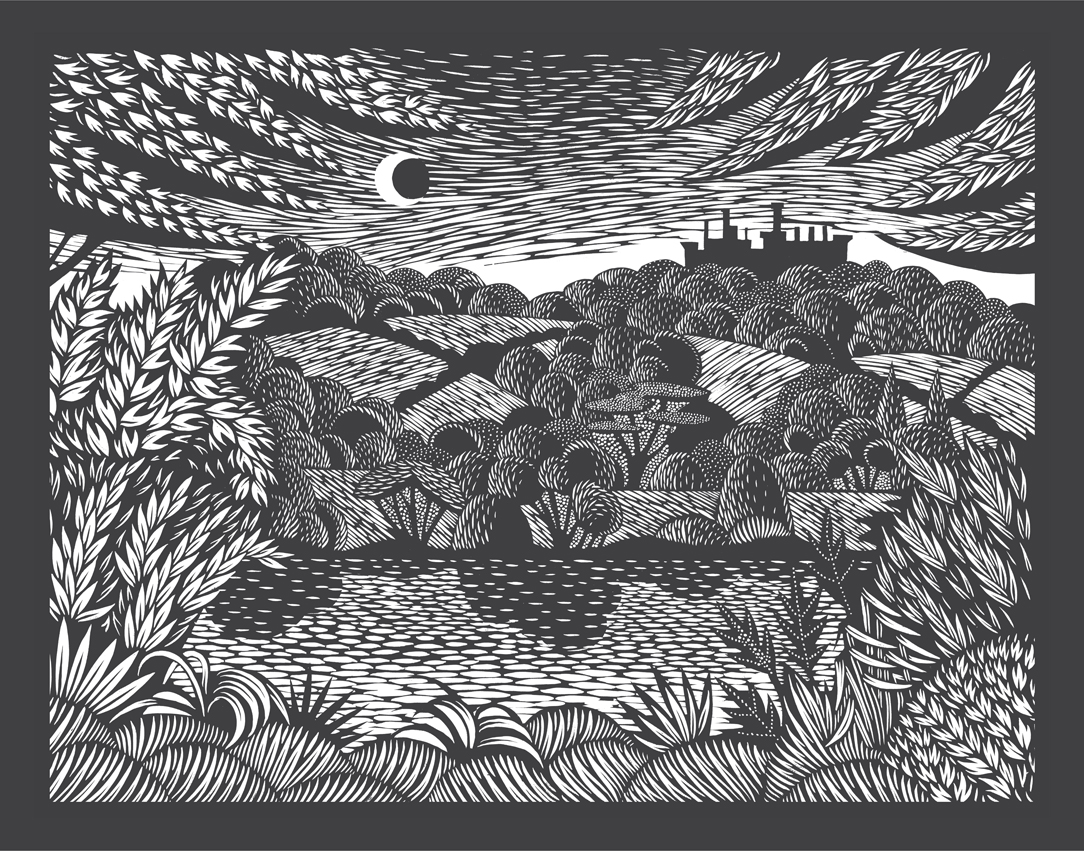

I see Belvoir Castle at the top of the first slope out of Bottesford. Dark blue against the sky, the castle stands on a lonely wooded outcrop, a heavy stone paperweight on the patchwork quilt farmland of the Vale of Belvoir, the gravitational core of the land. There it is on every turn of the road, getting slowly bigger as I bike towards it. At the foot of the castle car park, I turn right, and ride widdershins around the entire estate, sussing out the best way in. There are no walls around the duke’s land, just curtains of trees, occasional loose barbed-wire fencing and the implicit understanding of forbidden ground. I pedal for miles up and down the hills, through various villages that surround the estate, until I arrive at a long, straight road crossing flat plains of cow-cropped grass. The castle is there at the top of the road, on its plinth of wooded stone and beneath me, a small stream cuts underneath a stone bridge, straight into the estate. I decide to enter this way, grateful for the cover of its tunnel of trees. I hide my bike under the bridge, take off my boots and trousers and step in.

The silt sucks at my bare feet and tiny black fish dart like brushstrokes. I find a stick to help me through, and already know this is the single least practical idea I have had all year. Covered by a single line of trees on either side, I follow the meander of the river through alternate pools of gold and green, light and shade. The riverbed is lined in places with slabs of rough concrete, and at others with thick beds of gritty loam that farts and belches at my shins as they sink into it. Between the leaves of the trees, the castle is watching.

When Eleanor married her earl, this castle was in ruins, vacant for a hundred years. Five years after the wedding, the earl began to rebuild the castle, an enterprise that was greatly aided when Henry VIII dissolved the monasteries, allowing him to plunder the stone from both Belvoir Priory and Croxton Abbey. The castle was not just a refurbished house for the newlyweds, but a stark sign to the surrounding countryside that order was being reinstated. Outside of the court the life of women was much freer. When the Elizabethan writer Thomas Harman published his popular discourse on vagabondage in 1566 he described the men as ‘wily foxes’, in other words cunning thieves. But his description of women reveals that typical gendered fear of freedom: a masterless woman was a ‘cow … that goes to bull every moon, with what bull she cares not’. The men were work-shy, the women were sluts.

The commons were crawling with dissidents, spawning sedition on the plains beneath the watchful, fearful eye of the lords. William Tyndale had been burned the same year that Henry had begun his dissolution of the monasteries and several years later, with his translation of the Bible leaking through the common orders, he had prised open Pandora’s box: over the next century a host of sects and cults evolved, spreading alternative interpretations of the word of God. The Family of Love, the Quakers, the Fifth Monarchists, the Seekers and Ranters, Grindletonians and Anabaptists and countless others were creating their own decoctions of sedition and heresy, rejecting the dogma of resurrection, prayer, heaven and hell and principal among them all, rejecting subordination of any kind. Many were sexual revolutionaries, some rejecting monogamy, some rejecting marriage and most proclaiming equal rights across the perceived partition of gender.

Women were central to this sedition. They were core members of most of these new sects and just as active as the men in pulling down the fences and hedges around their commons. The arguments against land and its enclosure were the same arguments for their freedom of will – as the lords of the manor tried to enclose their livelihoods, they sought to extend their dogma on the role and behaviour of women. Strong, self-willed women of the courts were dealt with brutally. Anne Askew was the daughter of a wealthy landowner, and one of the earliest English female poets. She was the first woman on record to ask for a divorce. She converted from Catholicism to Protestantism and was charged with heresy in 1545. Although she was tortured in the Tower of London, she refused to betray the names of other Protestants and was sentenced to death in 1546. Since her broken bones could no longer sustain her weight, she was carried to her pyre on a chair, and when she refused to renounce her beliefs she was burned alive. Similarly, Margaret Cheyney was executed for her part in the Pilgrimage of Grace, for persuading her husband Lord Bulmer to get involved and for conspiring to recruit the locals to, in her words, ‘raise the commons’.

But the women of the commons, the working-class women, were harder to control, not least because there were a lot more of them. If the life blood of sedition is communication, these women, labouring in the commons, or spinning and weaving in rooms together, were the beating heart of the problem. The word gossip betrays this fearful link between the older women of the commons, and the spread of seditious counter-narratives. It began its life as a noun, godsibb. The godsibbs were the close friends of a woman who attended her in childbirth, and as such had a bond with the child and mother through the hours of labour. Men weren’t included. The word came to be associated with the notion of a close confidante and finally, through the Tudor period, evolved into a verb – to exchange closely guarded secrets. In Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus, Aaron speaks of ‘a long-tongued babbling gossip’ who threatens to reveal the truth of his actions and resolves to murder her to keep it quiet. He ends his speech with the lines:

The midwife and the nurse well made away,

Then let the ladies tattle what they please.

But the lords of Tudor England were not content to let the ladies tattle. In 1486, two German Dominican monks had published a work that became incredibly popular with the higher echelons of European society. The Malleus Maleficarum (The Hammer of the Witches) was the first blow against the working-class women of the commons. Divided into a list of questions, it was a handbook for the paternalism of the Church. Question Ten enquired: ‘Whether Witches can by some Glamour Change Men into Beasts’. So powerful were the words of women that they could turn ordered male creatures into feral heretics. The word glamour is the giveaway – the men were seeking to link these dissidents with the gypsies that were already spreading through Europe and heading to England. They sought to take integral components of the rural community and ostracise them as outsiders. The following question deals with one of the Church’s central paranoias, a woman’s control over her own body. Its answer states: ‘No one does more harm to the Catholic faith than midwives.’ In Catholic Europe it was heresy for a man to ejaculate outside a woman’s vagina (a rule that has the distinct hallmark of male authorship). Any interruption to the insemination of holy seed was flaunting the will of God. As such, these ‘cunning women’ and some men were committing heresy when they advised on various herbs for contraception and especially so when they performed abortions – a woman’s womb belonged first to God the Father, and then to the lord her husband. Matilda Joslyn Gage, a nineteenth-century suffragist, activist and author, wrote that ‘the superior learning of witches was recognised in the widely extended belief of their ability to work miracles. The witch was in reality the profoundest thinker, the most advanced scientist of those ages . . . as knowledge has ever been power, the church feared its use in women’s hands, and levelled its deadliest blows at her.’

Paracelsus, the father of modern medicine, once claimed that he learned everything he knew from a ‘cunning woman’. The knowledge these women possessed was accumulated from an oral tradition, passed along a generational thread of storytelling, and the experience of working within nature – many of their ‘sorceries’ have later been proved by modern science, and privatised by drug companies. A commoner complains of inflamed joints: ‘apply willow bark’, said the witches. ‘Sorcery!’ cried the Church. And today salacin, a chemical compound sourced from willow bark, is treated to make salicylic acid, which is now sold as aspirin. In 1540, Henry VIII granted the charter for the Company of Barber-Surgeons which was the beginning of the male-dominated medical profession. By law, women were barred from professional practice and anyone offering medical advice without a licence was operating outside the law. Surgery became the art of the male doctor and the holistic services provided by the cunning women, both psycho-spiritual (therapy) and herbal remedies, were outlawed. The herbs of the common had become weeds, the women of the common were witches.

Of course the Church had something to say about sexuality. As gender scholar Silvia Federici writes:

The witch hunt condemned female sexuality as the source of every evil, but it was also the main vehicle of a broad reconstruction of sexual life that, conforming with the new capitalist work-discipline, criminalised any sexual activity that threatened procreation, the transmission of property within the family, or took time and energy away from work.

Hags and crones were the worst of these: older women, whose bodies had finally liberated them from the consequences of fertility, were able to have sex with whom they pleased, and, worse, get away with it. This was a particular fixation for the Tudor judges. There is barely an account of a witch trial that does not go into lurid detail about an older women’s sexual union with the devil, some animal or a whole string of quaking, victimised men seduced by her ‘glamour’.

My passage through the river is blocked by a low stone bridge, laced with slack barbed wire. Spider webs lattice the archway, their drag lines extending in diagonals across the semi-circle of space, tethering their nets. The whole space is strung like a mandolin, taut with the report of delicate vibrations that communicate the world to the near-sightless spiders. I can see the swathed cocoons of their young, some still unhatched, and my spine prickles at the thought of hundreds of spiderlings caught in my hair. The Scythian traveller Anacharsis once likened the laws of the land to these webs. Recorded by Plutarch in 75AD he told Solon: ‘These decrees of yours are no different from spiders’ webs. They’ll restrain anyone weak and insignificant who gets caught in them, but they’ll be torn to shreds by people with power and wealth.’

This is the end of the river tunnel: on the other side of the fence, the river opens up to wide fields and sunshine but, on this side, its banks are lined on either side with wire, snagged with little scruffs of sheep wool, and hawthorn trees that make escape through the riverbank impossible. I must pass my rucksack and shoes through the lines of wire and silk and chuck them to a cove beyond. Knee-deep in running water, bent double under the bridge, I feel like a novice troll, perilously close to a drenching. But I make it through and clamber out to bright blue skies, warm earth and the vigilant presence of the castle.

The bridge is in fact a Right of Way into the duke’s land, and a famous one at that. In 1893, a man called Harrison took this path into the duke’s land to protest the grouse shooting on the estate. As he had done several times before, he waved his brolly and raised his voice to scare away the birds but on this occasion he was ‘forcibly detained’ (sat on) by the duke’s servants. He took them to court for assault. The judge, Lord Esher, found against him, saying: ‘on the ground that the plaintiff was on the highway, the soil of which belonged to the Duke of Rutland, not for the purpose of using it in order to pass and repass, or for any reasonable or usual mode of using the highway as a highway, I think he was a trespasser.’

I am following the river across the gnarly, rutted land where the long, open plains of grass meet the river. There are tractor tracks and large squelchy depressions, stippled by heavy hooves, where the cows come to drink. Herds of sheep stare at me as I pass and then suddenly bolt as one across the plains. There is no one in sight for miles around but still I feel a nagging anxiety: the heavy presence of the castle follows me, like Mona Lisa’s eyes.

When philosopher Jeremy Bentham returned from Belarus in 1787 he had plans for a new prison he called the Panopticon. Designed around a circular footprint, its revolutionary idea was that prisoners could be seen at all times from a central observation tower. The point, however, was not that they were constantly monitored, but that their behaviour could be controlled by the constant feeling of being observed. Two hundred years later, Foucault called this Panopticism, that sense of a higher power constantly surveying the actions of its lower orders. But here, beneath the castle, Panopticism seems to have been a much earlier invention. John Graunt, the Tudor pamphleteer, wrote in 1662: ‘Many of the poorer parishioners through neglect do perish, and many vicious persons get liberty to live as they please, for want of some heedful eye to overlook them.’ When the duke began his repairs of Belvoir Castle, he was reinstating this heedful eye over the Vale, a lighthouse of control that emitted not light but power.

These common lands, areas as yet ungoverned by the cult of exclusion, were places outside the scope of this heedful eye, places where women and men could live as they pleased. The Tudor courts told stories of Wild Sabbats on the plains and in the forests, great satanic orgies where men and women would come together to spurn the word of God and the order of the lords with sex and booze and dance. The word ‘coven’, used to describe these meetings, is derived from the same root as ‘convention’ and ‘convent’: it means simply a coming together of people. It was another one of Tyndale’s legacies: the congregation without the Church. The problem for the lords was that the connections they made on these wild plains, the solidarity they fostered, had constructed an organic, self-governing web of social relations, customs, that risked spilling over into the rigid hierarchal structure of the courts, even toppling them. Claire Askew is a poet and descendant of Anne:

you burned her: do it

because we took the plain

thoughts from our own heads

into the square, and spoke.

Anne Askew was burned because she brought her plain thoughts, her direct and unadorned opinions, into the square, the public sphere, the realm controlled by men of power. But perhaps there is a secondary meaning here – these plain thoughts could also refer to the plains on which I’m walking now, the sentiments and sedition of the commons, the only place where the lords of the manor couldn’t stifle the voice of women.

I have made my way through the open plains on the foothills of the castle and have come to a tarmac road. On my left is the head of an ornamental lake, which the duke rents out to local fishermen. There are plastic numbers staked into the ground at various intervals and semi-circles of grass cut from the reeds. I follow the road along the lake, passing the Duke of Rutland’s kennels, home to his world-famous bloodline of hunting hounds. I head over the bridge to the other side of the lake. I’m searching for a place to spend the night and here, in the flats of the great hill that leads up to the edge of the estate, the grass is up to my thighs, long enough to hide a sleeping bag and its contents. The fishing coves on this side have small fences and gates around their perimeter, and I am drawn to their added sense of seclusion. I shut the gate behind me, dump my bag, remove my boots and dip my feet back into the cold water, putting my t-shirt on the fence to dry. If I keep to the corner I will be snug behind the tall grass, hidden on either side by bulrushes, and the castle will be dead centre in my view.

In 1613 the two young sons of the 6th Earl of Rutland fell seriously and mysteriously ill. Henry, the oldest, died in September of that year and for seven years Francis lay in bed, weakening inexplicably, until he too died. For five years after the first death, rumours circulated that three women who lived in Bottesford had cursed the children in vengeance for having been dismissed by the Countess of Rutland. Joan Flowers and her two daughters, Margaret and Philippa, had all worked as cleaners in the castle but were sacked following accusations by other servants that they were thieving from the pantry.

The women were already suspect. Joan was a widow, which meant that she lived outside the protective couvert of a husband. As such her weak mind was susceptible to the lewd advances of the devil. On top of this, she was a ‘cunning woman’, she knew her roots and herbs, and there were rumours that their house was being used as a brothel. To make matters worse, she never went to church, and had been caught several times swearing on a Sunday. She was, according to one contemporary source: ‘a monstrous malicious woman, full of imprecations irreligious and for anything they saw by her, a plaine atheist.’

As Francis Manners took another turn for the worse, his mother decided it was time to act. Just before Christmas 1618 an unnamed person made an accusation against Joan and her daughters, claiming they had cursed the duke’s two sons by means of witchcraft. The women were rounded up and taken to prison to await trial.

Only now do I realise how late it is. The day has cooled quickly, and the sun has long since set behind the castle. Bats are beginning to flit above me, and the sky has turned a low violet. I unpack my sleeping bag, lay out the roll mat and cocoon myself from the chilling wind. I remember the fire I had on the Duke of Norfolk’s Arundel estate, the truck that had struck the fear of God into me as it rolled by. The driver must simply not have noticed me, but, with the fire blazing behind me, it had felt like a miracle. Tonight I am too exposed for a fire, but, cloaked in darkness, I still feel that same deep sense of unease beneath the squat, stone, heedful eye of the castle.

Today the term ‘witch-hunt’ evokes an inescapable accusation, a foregone conclusion that seeks only the evidence to corroborate the charge. But with the facts of this actual witch-hunt comes a shuddering realisation just how fenced in these women were. Three working-class women were facing the very essence of the patriarchy. First came the ‘examinations’ by a group of the most powerful men in the country. Among the men appointed were the Sheriff of Leicester, a Justice of the Peace and the rector of Bottesford. George Manners was there, the duke’s brother, MP of Lincolnshire, and a major landowner. And, finally, the duke himself, Francis, who was a Knight of the Garter, the original and most prestigious old boys’ club, Lord-Lieutenant of Lincolnshire, member of the privy council, not to mention the father of the ‘murdered’ child. When two of the women came to trial, they faced an all-male jury, because only property-owning men aged between twenty-one and seventy were deemed of solid enough mind to condemn evil in the face of the devil. The judges, who were handpicked by the king, were Sir Henry Hobart, the former Attorney-General and Lord Chief Justice of the Common Pleas, and Sir Edward Bromley, a baron of the Exchequer who was riding high in the king’s estimation having hanged the Pendle witches seven years previously. In Tracey Borman’s words: ‘The closed incestuous world of the local aristocracy and justice system was not exclusive to Lincolnshire: it was mirrored in every part of the country and underpinned the entire administration of the local and central government.’

Perhaps the word ‘patriarchy’ is unhelpful. Since the 1970s, it has been used to define power inequalities between the sexes on all levels of the hierarchy. But originally the rule of the father was a hierarchy installed by the Church and then borrowed by the state; it was a structure of power relations, from the top to the bottom. A father was the apex of the family power pyramid. Like a king or a pope, he was responsible for their welfare, and also for their discipline – he controlled their couverture. Perhaps paternalism is more accurate in describing the system that faced the women of Bottesford. Because what characterised these witch-hunts was not just gender but this particular structure of power. Across Europe, a quarter of witches killed were men (in Iceland, it was 92 per cent). And in England it was a woman, Elizabeth I, who reintroduced the death penalty for witches. The witch-hunts sought to eliminate not women, but what women represented in the minds of the lords: the dangerous disorder of the feminine.

Central to paternalism is the notion of the status quo: that its form of government is the only viable option. Through history, the concept of the feminine has been linked by the patriarchy to sedition, protest, any form of questioning this status quo. Sometimes the link was empowering: during the Welsh tax uprisings in the 1840s, known as the Rebecca Riots, men wore women’s clothes to tear down the toll booths; during the riots against the Game Acts in the early nineteenth century, men wore dresses to ransack the landed gentry of their deer, a clear symbol of sedition to the established order. But historically, and right up to the present day, most allusions to the feminine are pejorative. When the abolitionists argued against slavery in Parliament, they were feminised by their opponents, criticised for being too sentimental, too emotional to recognise the commercial necessity of free labour. Even in the core of Margaret Thatcher’s government, ministers who didn’t fully accept her hard-line neo-liberal ethics were labelled ‘wets’ when they opposed her, that is, effete, feeble-minded, incapable of power. It was Thatcher who coined the famous mantra that turned paternalism into a creed for neo-liberalism: ‘There is no alternative.’

I have been trying to sleep, but it’s not happening; it’s too cold. I hear a hoarse cough from the woods over the lake, a deer or a muntjac perhaps, and, suddenly stirred, the dogs begin baying from the kennels, breaching the eerie silence of the lake, a baleful sound of white-eyed bloodlust, pealing like church bells, which starts the geese off, and then the coots, and now the dark lake is a cacophony of whoops, hoots, screams and howls, a wild sabbat of hidden creatures on the common. I lie like the effigies of the earls in the church, petrified.

Joan Flower never made it to trial. She died on the long winter walk in between Bottesford and the Lincoln court. Somewhat unbelievably, she choked on a piece of holy bread, which in the spirit of the times was proof enough of her witchcraft for her guards not to be accused of malpractice. Her two daughters were tried, however, and the court found them guilty of crimes ‘against the peace of the Crown and the dignity of the Lord King’. They were hanged slowly, to avoid snapping their necks, strangled and suffocated by the noose until their tongues were disgorged from their throats.

I watch the stars fade away and the sky turn from dark blue to grey. I must have slept, but I don’t feel it: my head is spinning, my eyes are burning, I’m cold to the bone. I get up stiffly and pack up everything around me, leaving nothing on the ground but a cold dent in the grass. As I turn to leave the enclosure, I hear the dogs again, this time louder, and the bark of a man commanding them. My heart flashes. The dogs are there in front of me, ranging over the hillside, a sprawling pack hungry for exercise, and three figures on horseback galloping them on. I’m too tired to move and so stand, stock still, as they disappear. I wait a while and then follow them cautiously up the valley from the lake, beneath the boughs of huge cedar trees and emerge out onto a common. Cows are gently milling through the scrub, one rubbing her head satisfyingly against a monkey puzzle tree. And at the end of the common, on the top of a steep slope, there is a triangle of sunshine, golden grass, warmth.

I sit on the slope and eat a banana, the entire Vale of Belvoir spread out before my feet, a picture of peace and order beneath the castle. In a 2015 BBC documentary, the current Duchess of Rutland says: ‘The building itself is so imposing, it takes people’s breath away.’ For the three women of Bottesford, this was true in its most literal sense. Today, you can visit the castle at Halloween and ‘listen to eerie stories about the Witches of Belvoir and make creepy crafts!’ The murder of three women, and their alternative vision of power, has been redefined and reconstituted as anodyne tourism, the weeds of eccentricity ploughed into fields of monoculture. Then, as now, the web of hedges and plough lines that extends over the Vale drains both the yield of the land and the power of the people to one source, the heedful eye of the castle.

Here were the lords of the law because here were the lords of the land. Their control over the commoners came after their control of the commons. Any threat to this order, any alternative distribution of power, was a direct challenge to this order of the land, the order of property. But this order, which masquerades as the order, was only ever their order.

In 1981, a group of thirty-six women aged between twenty-five and seventy set off on foot from Cardiff City Hall to a patch of common land in Berkshire. With a few men and a few children accompanying them, for ten days they walked along the verges of motorways and A-roads. At the head of their column, the women took turns to hold a sign. On the front it said ‘Why are we walking 120 miles from a nuclear weapons factory in Cardiff to a site for cruise missiles in Berkshire?’ On the back were the words ‘This is Why’ and, below, an enlarged photograph of the corpse of a baby, born dead and deformed in the aftermath of the Hiroshima bomb.

At first, the walk itself was the protest. But their arrival at Greenham Common was something of an anticlimax. The press coverage along the way, national and local, had focused not on the substance of their cause but on something they considered far more remarkable. Helen John, a midwife on the protest, wrote later: ‘All they asked about was how our husbands were coping back home, and weren’t we irresponsible exposing our children to all that carbon monoxide’.

Above and beyond the threat of nuclear annihilation, the press were astounded that these women had the gall to leave their domestic enclosure and trespass the public sphere, the realm of men-who-know-better. When they arrived on the common, they gathered at the gates of the American Air Force base and read out the speech they had co-written, surprising the guard on duty who had assumed they were cleaners. When another guard turned up, he informed them that, since it was a Saturday night, the guys on the inside of the base were hitting the Jack Daniel’s and, unless they wanted a good raping they’d better move on. Eventually the US base commander appeared. The women again read out their statement. ‘We will not be victims in a war which is not our making. We wish neither to be the initiators nor the targets of a nuclear holocaust.’ To which the commander replied he would like to machine-gun the whole damned lot of them. ‘As far as I’m concerned,’ he said, ‘you can stay there as long as you like.’ So, for nineteen years, they did.

In 1939, 900 acres of common land was enclosed as a base for the Royal Air Force. Nine miles of barbed-wire fencing went up and the common was tarmacked over. After the war, the MOD bought the site and by the late 1960s it had been leased to the American Air Force. There was room for 2,000–4,000 troops and their wives and children to be stationed there. There was a school, cinema and shopping centre for American personnel and then, a decade later, six trapezoid missile silos, turfed with grass. In 1979, Ronald Regan announced that ninety-six MX ground-launch nuclear missiles would be installed at the site. Just for a laugh, he called his explosives ‘The Peacemakers’, because there’s nothing quite so peaceful as a nuclear winter.

Today at Greenham Common the missiles have gone. The common has been opened up for dog walkers and cyclists and the RAF control tower is a tea shop. Part of the fence still remains, ten foot high, with iron arms angling over its face holding three lines of barbed wire, rusted brown. It now appears to be a car park for a van hire company, policed not by the American Air Force but by two bored-looking men in hi-vis jackets. But forty miles east, on the outskirts of London, there is another protest camp built on similar principles of the women of Greenham. They are protesting what is perhaps the only thing more devastating than nuclear war: the total collapse of the environment, formerly known as climate change. They have squatted a few acres of derelict land in a village called Sipson, just outside Heathrow Airport, which will be entirely flattened under tarmac if the proposed third runway is built. The Diggers and Dreamers’ website describes the camp, which is called ‘Grow Heathrow’: ‘Since 2010 a group of activists, local residents and people living off-grid have worked to develop the site into a self-sustaining low carbon community, and to be a community centre/host for groups, events & activists.’

The site is open to anyone who comes, and so, seeking not the land but the spirit of Greenham, I go to Grow Heathrow, during a cold snap at the start of the new year.

I have come for a ceramics workshop run by Jessica, a woman who lives nearby. I walk up a muddy avenue of makeshift huts, recommissioned sheds raised on foundations of builders’ palettes and layered with insulation and rain-proofing. The site is an open-cast rabbit warren of woodchip paths cut through the brambles, leading from one cluster of structures to another. There are tree houses, common rooms, fire pits encircled with cut logs as seats. There is a watchtower at the centre, a construction of scaffold and a wind turbine, that turns the stiff wind into hot water for showers below. There are two large boats on stacks at the end of the first avenue, draped in tarp, and the central community hut, which is also the kitchen, where smoke chuffs out of the stove pipe in the roof. One of the residents leads me through a skeleton greenhouse, past raised grow beds made from sawn tree trunks, down into the group space, where people have already begun shaping the clay.

Jessica is several years out of Camberwell College of Arts. She is working on a project to commemorate sites of protests in the history of English land rights, as important as they are unacknowledged. She trespasses the land, digs a chunk of earth, bags it and escapes like a cartoon robber with her swag slung over her shoulder. She has excavated St George’s Hill, the site of the Diggers’ revolt that was crushed by Cromwell’s army – now a golf course – and is in the process of scoping out Mousehold Heath just outside Norwich, where landowner Robert Kett helped 16,000 commoners tear down his own hedge enclosures, and went on to storm Norwich. This is now also a golf course. Today we will be working with clay from Heathrow, dug from a six-foot trench at the corner of the site.

When the Greenham women set up camp that first night, their priority was to build a fire. When more and more people started coming, scores of people, then hundreds, then thousands, they brought tarps and palettes, hay bales, cut wood and food and started erecting benders, traditional gypsy structures made from bent hazel rods. When someone brought a huge cauldron, to cook for the congregation, the witches were finally in place, the coven was created.

Our living room was a fire pit surrounded by straw bales covered in plastic. There was always a kettle perched precariously on the smoking embers and whoever got up first relit the fire each morning. Our office was an old fridge in which we kept the letters to be answered. A chest of drawers contained other handy items like string and paper. Beyond the kitchen and living room, stretching down towards the main road, we’d strung a washing line between two trees and draped plastic over it to form a tunnel. Inside the tunnel we’d laid pallets covered with straw, this was the communal bedroom.

With no leader and no camp hierarchy, the camp evolved organically. Initially men were living alongside the women but, after a year of protest, it became clear that their presence escalated the aggression in clashes with police. A meeting was held, a vote was taken and men were banned from living at the camp. As if to prove the women’s point, they kicked off, one taking an axe to the structures he had helped build, but soon they had disappeared, returning only for day visits. And now the press started to take a greater interest. Was this a feminist protest, or an anti-nuclear protest?

The media have quite consistently and continuously avoided taking up our perspectives on war, racism and sexism … The confusion has been inside the camp as well as outside because every woman stands for herself and we try to live in a way that is respectful of our differences. Which comes first, disarmament or feminism? It always had to be one or the other – prioritizing. We say you can’t have one without the other.

The mass media has always preferred to particularise the concerns of a protest, to find the leader of a group and interview them for the single, simple soundbite; their columns are too slim to weave together the many threads of narrative that form the web. To the women of Greenham, however, there were multiple lines that had led them to this camp, and the web was formed of delicate nodes of intersectional concerns, none of which took precedence over the other. Power was arranged not vertically, in the top-down template of paternalism, but horizontally, where every thread of the web held the tension of the whole. As the camp grew, more threads were intertwined: the illegal mining of uranium in Namibia that built the bombs, the un-unionised labour that had laid the tarmac and fencing of the airbase. The camp became a howl against the paternalistic hierarchy, that grid of power that compartmentalised oppression and pretended that everything from the exploitation of women and labour to racism, colonialism and nuclear armament was neatly unconnected.

The image of the spider’s web emerged from this intrinsic feeling of connectivity to become the symbol of the camp. It expressed the many storylines that had led the women to the camp, the horizontal power share that the women had organised, and, on a practical level, the chain letters and telephone lines that connected the group to outside solidarity. The spider seemed to encapsulate every notion of the protest. For some it drew on that great Freudian Urangst, the primeval male fear of the woman as predator, the spider that eats its mate. For some it drew on the Greek myth of Arachne, the weaver who used her thread to lead Theseus out of the man-made labyrinth, out of the straight corridors of the masculine psyche, into the open plains of the feminine. Some drew on the Native American myths, in which spider webs were woven from thread to catch dreams, to manifest hope, and the great spider mother of the Navajos, who wove strong silk to protect human life. Further south, the Mexican spider grandmother, Teotihuacan, represented the queen of all creation, Mother Earth. The web was a symbol of a protective field, the ability to use arts and creative thinking to create another world, the ability to listen sensitively to the vibrations around oneself, to be attuned to one’s environment. It was also a symbol of persistence: the ability to keep remaking the web no matter how many big beasts crash through it.

Fundamental to the Greenham spirit were the spider trickster gods. Like the coyote and the hare, the spider trickster is able to utilise creative vision and cunning to thwart the powerful oppressor, to creep through the cracks of their fortress and come out on top. And so the spider came to represent one of the Greenham women’s key strategies: creative, artistic, non-violent direct action. ‘I don’t see non-violence as just a tactic,’ said Rebecca Johnson, one resident of the camp. ‘It is part of the accepted lie that violence is more powerful that non-violence and that people can somehow save themselves from violence by taking up arms. Thus non-violence is viewed as less valid, less desperate – a sort of liberal pastime.’ In fact, non-violence was itself a threat to the order of things, a refusal to meet the hierarchy on its own terms.

The Greenham women worked tirelessly to find creative ways of protesting the base. They would blockade the base to prevent missile carriers from entering, sitting on the wet ground, arms linked, singing a whole songbook of protest songs they had conceived during the long days under the rain-bashed tarp:

The fragile docile image of our sex must die

Through centuries of silence we are screaming into action.

We’re shameless hussies

And we don’t give a damn.

Daily they would take their wool to the fences and lamp-posts and barbed wire and appropriate the austere military infrastructure as a canvas for creativity. Keening played a huge part in the camp’s sense of solidarity. From the Irish tradition of caoineadh, a key component to the pagan wake ceremonies, keening was a loud, long guttural wail, a lament for the children that had died, and would die, in nuclear war. Against the cold silence and blank faces of the military personnel, it was an eerie breach of the peace, an explosion of emotion from a tightly bound nucleus of pain.

In December 1982 they used their telephone lines and chain letters to organise a huge demonstration, the first year with 30,000 women, the next with 50,000. They drove, bussed and walked from across the country to be there, spread out along the nine-mile-long perimeter fence, held hands and enclosed the enclosure with song. They decorated it with woollen webs, drawings, their children’s teddy bears, photographs of their babies, bringing the cherished items from the home to the base that threatened its sanctity. It was a poetic, incongruous and deeply unsettling act, bridging the psychological gap between the perpetrators of a possible nuclear war and its future victims. Geographer Tim Cresswell called it ‘a type of secular magic’, the ability to eradicate the perceptual partition between the clean order of the military base and the ragged mess of burned flesh it threatened.

It was a defining moment in the camp’s ideology when the coven decided to cut the fence. Did this count as violence? On Halloween 1983, 2,000 women dressed as witches stormed the fence and tore down five of its nine miles with bolt-cutters. So many were arrested they had to be held at Newbury Racecourse as they were processed through the night. Theresa, another member of the Greenham camp, wrote:

Taking down the fence was, for me, a most powerful celebration, and expression of ‘NO’. No to the machine and the barriers it creates, the fence being a visible, physical barrier but no also to those invisible ones that keep us so alienated, east from west, black from white, heterosexual from homosexual, barriers of class, religion, barriers of privilege and deprivation …

Living day in and day out in front of the base, the women began to see the fence not as the blank, impervious wall of the system, but as a porous membrane, through which they could engage the stony-faced guards and remind them of their own humanity, their own children. On the second Embrace the Base, 50,000 women brought mirrors with them and held them towards the base, reflecting the image back at the soldiers, turning the blank statement of the base back onto itself, interrupting its authoritarian laser glare with its own mask.

As the camp grew organically, it became as much a protest for as against. It had evolved into a new anarchic society, a bubble both outside and deep within the established order of society. This no-man-land was a no-man’s-land between two expressions of order – on one side of the fence, the paternalistic inevitability of nuclear armament, the projection of power by threat of violence; on the other side of the fence, the neat English countryside in which women were expected to know their place, a world that had defined and confined women into roles written by men. In the slim space between, the women had woven their own web of relationships that refused to conform to the partitions imposed on them. Theirs was a space where womanhood was self-defined, where womanhood was powerful, where womanhood was no longer ostracised to the margins of public debate. The witches had reclaimed the common.

I have taken a break from the workshop and am making tea for the group in the large shack by the entrance, the common room and kitchen. There is a battered Aga in the corner, alongside a variety of shelves and surfaces built out of reclaimed wood, covered in chipped mugs and coffee grains. Above the sink, someone has written: ‘To attain true enlightenment one must learn to do the washing up.’ Like Greenham, the horizontal power share of this place gives it a rare quality: no order has been imposed from above, it adheres to no blueprint, homogeny has rotted under a wild spurge of creativity. No one area looks the same as another: everything reflects the mind of its conceiver, bears the handprint of its builders. With the constant flow of protesters and local residents pumping through its veins, with the repurposing of its areas, the constant changing of its skin, the organic development of its structures through the thought and work its residents put into it, the camp grows like a tree in proportion to the resources on offer; it is as close to a living thing as a place might be. I fill the kettle, put it on the stove and turn to split some wood with the axe. I open the door of the Aga and layer up the kindling, and I feel the roar of its fire on my face. I’m looking into the heart of the camp, the nucleus around which everything survives. Home is where the hearth is.

Foucault had a word for places such as these. He called them heterotopias – spaces of outsiders forged deep inside society, spaces that reflect the orthodoxy of that society by arranging themselves differently. These spaces are distinct from utopias in that they are real, they actually exist, and they manifest their ideologies in real space. Someone has done the plumbing, set up the solar panels, dug the long-drop compost toilet. They work; there are alternatives. This is a message that the Fathers find profoundly threatening.

In Greenham, the media continued as they had begun. Everything was not in its right place. There was an appalled sense of the women’s dereliction of duty, that by leaving their appointed geographical identity, their home, they had deserted their very womanhood. As Cresswell writes:

An analysis of the media response reveals the boundaries of assumed, normative geographies. The divisions of mad/sane, good/evil, criminal/law-abiding and normal/abnormal that appear so frequently in the press discourse all have geographic foundations in the assumed displacement of women from the home and family to the all-women environment of the camp.

These women had transgressed their geographic normativity and trespassed into a world that was not for them. The media fixated on the squalor of the camp, and by extension the filth of its women. Auberon Waugh claimed the women smelled of ‘fish paste and bad oysters’ and the Daily Mail reported that local police dreaded ‘being ordered to lay hands on women who often deliberately and calculatingly stink’.

What these reports ignored is the fact that the council had banned the use of chemical toilets and were constantly removing the women’s standpipe (which they used to access water) in a direct bid to make conditions inhabitable. But there is a deeper, more primal element to this obsession with dirt. The concept of woman in society was then intrinsically associated with perfume adverts and cleaning products, but on the common these mud-spattered women were shattering these sensual projections of men and that centuries-old enclosure of purity. As anthropologist Mary Douglas says: ‘Dirt is matter out of place’; out of the home, in front of the clean order of the military base, these women were dirt.

Of course, as with the witch trials there was a salacious interest in sexuality. Sarah Bond was a reporter for the Daily Express who went undercover in the Greenham camp. She went around counting lesbians: ‘Half the women I lived among at Greenham were lesbians, striding the camp with their butch haircuts boots and boiler-suits. They flaunt their sexuality, boast about it, joke about it.’

Here, the homophobia of flaunt is married with the misogyny of boast, exposing not so much the reporter’s bigotry, but her innate sense of territorial orthodoxy: these are things that should be hidden away, they do not belong in the public sphere.

The residents of Newbury also responded viscerally. They formed an alliance called Ratepayers Against the Greenham Encampment (yes, RAGE), which organised constant vigilante attacks on the women. Dog shit was thrown, pig shit and buckets of maggots; the camp was set ablaze on various occasions. Signs went up in pubs, ‘No Peacecampers’, and the local Little Chef banned Greenham women, an illegal act that was supported by teams of police officers. Three years into the camp, one local resident organised a plane with a banner to fly across the common, breaking innumerable laws and national security measures, not to mention trespassing the airspace, with no complaint from the police or MOD. The banner, in three short words, surmised the central crux of the horror, the geographical dogma these women had broken: GO HOME GIRLS.

The women of Greenham were resented not for the spells they cast, in song and woven nets, but for the spells they were breaking. Before the women arrived, the camp comprised neat tarmac roads, triplicate fencing and rolls of barbed wire. It was a trance of order that blinded England to the base’s devastating potential. Within the perimeter fence was the hardware to destroy half of England, each of Reagan’s Peacemakers possessing the destructive capability of sixteen Hiroshima bombs. On top of this, the site itself raised the little Berkshire town of Newbury high on the Kremlin’s hit list for strategic retaliation – it was a new bull’s-eye for Russian rockets. But somehow, the Apollonian order of the camp was more seemly than the earthy, Dionysian protest against it. By constantly decorating the fence, the women called attention to its presence; by constantly perforating it, they tore holes not just in the fence, but in the matrix that justified it. And by simply being there, the women were breaking the spell of couverture, the spatial politics that kept them enclosed within the household. As Foucault says of heterotopias: ‘their role is to create a space of illusion that exposes every real space, all the sites inside of which human life is partitioned, as still more illusory.’ They were bursting the property bubble.

In Sipson, the village around the Grow Heathrow camp, the land has been almost entirely consumed by this bubble. In preparation for the third runway, and decades before it was given the green light, Heathrow Airport Holdings, a subsidiary of a private multinational firm called Ferrovial, have been buying up the land across the entire village, offering prices that depreciate with every passing year. By 2012, three-quarters of the village had been bought up and the houses it owns are now either vacant or rented to newcomers on short leases. The village has been ghosted away: crime has increased, the empty houses have been left to decay. Gerald Storr, the local butcher, is quoted in the Guardian: ‘There’s an almost tangible feeling of doom and desolation. People have given up and moved away.’ Sipson, or Sibbwineston as it is called in Domesday Book, was a community hub for at least a thousand years before the airport was built. With four other villages it shared rights to the local heath: a web of customs linked the villagers to the land and to each other. But when Harmondsworth Moor was enclosed in 1819, the connections between villages were cut by a fence and a new spell bound the land. And when the first airport was built in 1930, the row of cottages along the heath was elided like the space between the words: Heath Row became Heathrow.

By squatting the land, Grow Heathrow have burst the bubble of 200 years of enclosure. Their ethic of ‘positive alternatives’ has rewilded the rubbish heap, clearing it of thirty tonnes of industrial waste and using permaculture techniques to re-fertilise the soil. Through workshops, tea dances, music events and green-fingered volunteer work, local residents have come together once again; by digging the earth, they have unearthed the old root systems that connected them to the land – and to each other.

For the first two years of the Greenham women’s protest camp, the police were almost powerless to stop them. The evictions they ran were at best misnomers – they removed all the necessary infrastructure for survival, but the women remained. They could arrest protesters for breaching the peace, but only when the women lay in front of the missile carriers and obstructed the daily operations of the military. Because the camp was on common land, the women had every right to be there.

So the laws were changed. With the bang of a judge’s hammer, the council revoked the deeds of the common land. The Observer reported: ‘Previous attempts to evict the women have failed but council officials now believe they have found a way of silencing the politically embarrassing camper, by making anyone who walks on the land a trespasser.’ And this is the heart of the matter. At Belvoir Castle, Mr Harrison’s protest against the Duke of Rutland was deemed illegal, not because of the substance or style of his protest, but because he didn’t own the land. Even though he was on a public Right of Way, his ethical protest was silenced with trespass laws. When the council revoked the deeds to Greenham Common, they removed the women’s right to protest, a move justified not by ethics, or danger to society, but by property law.

Only recently have our rights to protest been secured in law. Article 10 of the European Convention for Human Rights (1953) ratifies our right for Freedom of Expression and Article 11 gives us a human right for Freedom of Assembly and Association. However, in England, the laws of private property trump our collective human rights, which means on private land neither of these rights apply.

Terra nullia was one of Emperor Justinian’s categories of land ownership, meaning land owned by no one. In England, there is no such thing. Public spaces, whether in towns or the countryside, are all owned. If they are owned by the council, then they have a duty to provide for public protest, but the councils across England have been selling off these spaces to private corporations or individuals, for improvement. When the Occupy movement went to protest the banking crisis outside the London Stock Exchange in 2011, they were thrown out of Paternoster Square by the private security guards of Mitsubishi Estate Co., who own the land. Signs went up saying: ‘Paternoster Square is private land. Any licence to the public to enter or cross this land is revoked forthwith … There is no implied or express permission to enter the premises or any part. Any such entry will constitute a trespass.’

London’s public spaces have been swiftly sold off to private companies, and the same is happening across the country. Go to Canary Wharf or the Bullring in Birmingham, or Liverpool One, now owned by the Duke of Westminster, and pull out a sign (any sign) and see how long it takes for you to be escorted off the premises, on to a public highway. Even there you might be chased up the street: with a ‘stopping-up order’ the council may have sold the public right of way to a private developer, removing the right of access and turning the road into a private drive. The Duke of Westminster now owns thirty-four streets in Liverpool city centre. You will have broken no law, you will simply be removed by the mobilicorpus of trespass and if you resist you will be breaching the peace, a charge of such wide, billowing parameters that it also hanged the witches of Belvoir.

In 1985, the then secretary of state Michael Heseltine introduced new by-laws for Greenham Common that upgraded the trespass into the camp to a criminal charge. Heseltine warned that the women could now be shot if they crossed the line. Appropriately enough, the new by-law came into effect on 1 April 1985, April Fool’s Day, and was instantly and deliberately contravened by the Greenham women, a hundred of whom were arrested that day. Using the trickster spirit of Anansi, that creative, slippery mindset, the women had inverted the power that was used on them: the new criminal trespass laws could aid their attempts to get their message heard. By dealing with the women on simple trespass charges, they were removed from the land and dealt with in civil court, with no jury or assembly of press. But under criminal charges these women had to go to court, where they could offer their plea, where their opinions would go on record. For this reason, to make sure they were arrested they labelled their bolt-cutters with their names. ‘In court,’ said the longest resident of the camp, Sarah Hipperson, ‘we had to be listened to.’

As a window into the scale of civil disobedience, Hansard recorded a total of 812 trespasses in the fifteen months from January 1987, each breach calculated to expose the flaws not just in the fence, but the legal systems that supported it. And it worked. After a four-year legal battle, the courts ruled that Heseltine had pushed aside a legal constraint in his quest to end the protest – he had acted ultra vires, beyond his powers, or, more literally, beyond his manhood. In 1992 the courts ruled that the fence itself had not been erected under ministerial consent and Judge Lait ruled ‘the perimeter fence at RAF Greenham Common was unlawful at all relevant times’. The fence was the crime, not the crossing of it.

The last of the Greenham women left the camp in the year 2000. Nineteen years in the mud. They were met with almost universal derision, their protest declared a failure. But in December 1987 Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev signed the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty and, two years later, the first missiles left Greenham. Of course, despite Gorbachev specifically referring to the role the Greenham women had played, the world was told that this would have happened anyway, that it was entirely unconnected to this coven of woolly-hatted, woolly-minded protesters. Of course: you wouldn’t want the word getting out.

In 1986, there were over 70,000 active nuclear weapons in the world; today, there are still 9,000 in active service, with 1,800 ready to fire at a moment’s notice. The Greenham women’s protest did not fully eliminate the danger of nuclear war, but the silk thread of the Greenham web, the line of resistance as persistence, runs through to the present day. As one of the protesters said ‘Greenham was powerful. It taught my generation about collective action, about protest as spectacle, a way of life … Greenham created an alternative world of unstoppable women.’

In June 2010, two women walked into Tate Liverpool with ten litres of molasses strapped in rubble sacks to their legs. Wearing long, pretty floral dresses, lipstick and mascara, they walked through the security at a prestigious evening annual event, the Tate Summer Party, all smiles and styles. That year, the party was bigger than ever – more politicians, more canapés, more art-world celebrities and more press: they were celebrating twenty years of sponsorship with British Petroleum. At exactly the same time, 5,000 miles away in the Gulf of Mexico, a total of 201 million US gallons of crude oil was pumping through a leak in BP’s oil pipes, as it had been doing, uncorked, for the past two months. When the two women had sipped their first flute of champagne, they walked into the middle of the hall, bent down and, with keys, they cut the sacks of molasses beneath their dresses. Onto the white polished floor flowed the thick black liquid, a secular magic trick that brought the filth of an oil spill right into the heart of the spectacle of order. But more than this, as the guests retreated from the mess, the two women had cleared themselves a rotunda, a space for theatre, a new spectacle of disorder. Before the eyes of the guests and the lenses of the national press, they put on BP-branded plastic ponchos and began cleaning up the mess on their hands and knees, smearing the oil over the polished floor. Don’t worry, they said, we’re handling this.

This was Licence to Spill, the inaugural performance of the newly formed Liberate Tate, an arts and performance collective aiming to end the sponsorship between the Tate and Big Oil. In the following years, they created a variety of performances, each strategically designed to make the news, to broadcast their alternative vision of the Tate’s marriage with BP. One of the performers, Mel Evans, went on to write a book called ArtWash, which details the relationship of Big Oil with art galleries across the world, describing the techniques they use to normalise their imperialist, colonial, ecologically toxic imperatives, by washing their stains in the clean, Apollonian temples of art galleries. The other performer, Anna Feigenbaum, co-authored a book called Protest Camps, which analyses, among others, the techniques and tensions of Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp. To say one action directly influenced the other misses the point of this silver thread of protest: the line extends through time, each action is another node that holds the web taut, each strengthens the other. And this thread continues to this day, in the anti-fracking protests in Preston, with Extinction Rebellion, both of whom use the lock-on techniques of the suffragists, the willingness to get arrested and non-violent direct action to burst the orthodoxy of paternalism.

After six years of persistent resistance by Liberate Tate, BP announced they would no longer be sponsoring the Tate Art Galleries. When asked about the efforts of Liberate Tate, a spokesperson said ‘They are free to express their points of view but our decision wasn’t influenced by that. It was a business decision.’ Of course …

It is vital for the status quo to appear as if it is the natural order of things, to proclaim the absolute lack of alternatives. The systems that create places such as Greenham Airbase or Heathrow Airport rely on the blank statement of inevitability, fused with the sense of futility in opposing it. A Daily Mail article on the Greenham peace camp claimed that ‘the women never really came to terms with how to respond to the inevitable’. Horizontal power structures, covens, communities that prioritise listening over telling are repeatedly dismissed as woolly, fanciful, feminine and weak. Doomed to fail. And yet they won the abolition of slavery, the right to vote, the right of gay marriage and just about any other human right that was not given by the lords, but taken by the commoners.

Here in Heathrow, in the dilapidated greenhouse, the light is dimming quickly and everyone else has disappeared, their pots and sculptures lined up on a shelf. Our fingers are waxy-white, frozen bloodless by the slip water we have been smoothing into the clay. As we scrape the table of its residue and sponge it down, Jessica is talking me through the alchemy of turning dirt into clay. When she returns from the site, she tips her sack of soil incrementally into a cauldron of water, into which the clay, with steady stirring, dissolves. She pours the solution through a fine sieve and discards the undissolved soil, leaving a thick filmy liquid, which carries the clay. She hangs this liquid in an upturned pillowcase, letting it drain for days, and then wraps it like fresh cheese in a muslin net, or an old t-shirt, and squeezes the remaining water from it. What remains is a glistening wet terracotta, a material which can be shaped and moulded to hold the creative visions of all that work it, which, when baked in the kiln, will harden into something real. Like the protest camp we stand in, she has reclaimed the earth from its title deeds and transformed it into something new.

Grow Heathrow was issued with eviction orders in 2012. The solicitors of the owners of the property stated: ‘while no doubt Grow Heathrow have put in a lot of work in clearing up and improving the site, at the end of the day this gives them no legal right to continue trespassing on the land.’ The protesters fought the order, and remained where they were for another seven years until the bailiffs appeared again, several weeks after I had visited the camp. This time, they came armed with the heavy heft of the law, with officers from the Met Police and a helicopter present to ‘prevent a breach of the peace’. The day of the eviction just so happened to be the hottest February day ever recorded in England. Half the camp was cleared. And though the protesters simply moved to the other half, whose owners had not yet filed for eviction, it began to look like the construction of Heathrow’s third runway was indeed inevitable. The power of the castle had again triumphed over the commons: protest silenced by the uncompromising paternalism of property.

But then, something magical: exactly one year later a court of appeal ruled that the plans for the third runway were ‘inconsistent’ with the government’s commitment to the Paris agreement on climate change. With this ruling, Heathrow’s plans for 700 more planes per day no longer just flew in the face of a greener future, they were also now illegal. This was the first major ruling to be based on the Paris agreement and its influence extends beyond Sipson, through England and out across the globe. It sets a precedent for the 194 states that signed the agreement, stating plainly that international climate agreements have a direct bearing on domestic decision-making for all future high-carbon projects. The alternative has been baked into law, the Earth has been transformed.

The case was brought by Plan B, a legal charity that represented a web of different vested interests, including environmental charities, volunteer campaigning groups and residents from various boroughs. At the centre of this web was a place where people could gather, the protest manifested into real space, the living embodiment of the alternatives: Grow Heathrow. But had the bailiffs been successful the first time round, or the second, this new world order could have been scuppered by the owners of a small plot of land in Sipson. It is in this way that control of the land turns into dominion of the Earth. The rights of the community of Sipson and the rights of the community of the planet would have been silenced, as they often are, by the most powerful and exiguous elite on earth: the lords of the land, the landlords.