Peers, parvenus, perquisites and peasants

A buck or doe, believe it so

A pheasant or a hare

Was put on earth for all who know

Quite equal for to share

– Anonymous, nineteenth-century folk song

The scene opens on the back of a golden retriever trotting faithfully at his master’s heels. Ahead of them, just out of focus, is an exotic cedar tree and the great, towering castle. We cut to the interior where, as if by magic, the shutters open on an opulent world, the servants’ bell, the silverware, the perfume bottle, the artsy falling rose petal, the careful brushing of the glittering glass of the crystal chandelier. Surging, insistent strings, the welling of irrepressible emotion, underpin a resolute piano motif, a sound that says there’s business to be done. The strings poise and the scene resolves into the programme’s masthead: the screen is split horizontally, the blue sky and celestial castle above, and below, its reflection, in negative, swathed in blackness. It is a strange, binary vision of heaven and hell, and it reads: Downton Abbey.

Running for six seasons, the television series Downton Abbey won a string of prestigious awards and glowed with critical acclaim. Sold to over 220 territories, by 2013 its estimated audience was 120 million. Downton Abbey is the newest in a long line of costumed melodrama that reflects the global demand for England’s foremost export and principal delusion: class.

The real Downton Abbey is Highclere Castle, in Hampshire, several miles south of Greenham Common. My friend and I enter like guests, through a smart driveway at the north end of the estate. Before it sweeps us round to the London Lodge, we cut off the tarmac onto a grass path through a dark green maze of tightly packed azaleas. The path opens up to a broad lake: ‘How scenical! How scenical!’ said Benjamin Disraeli when he first came here.

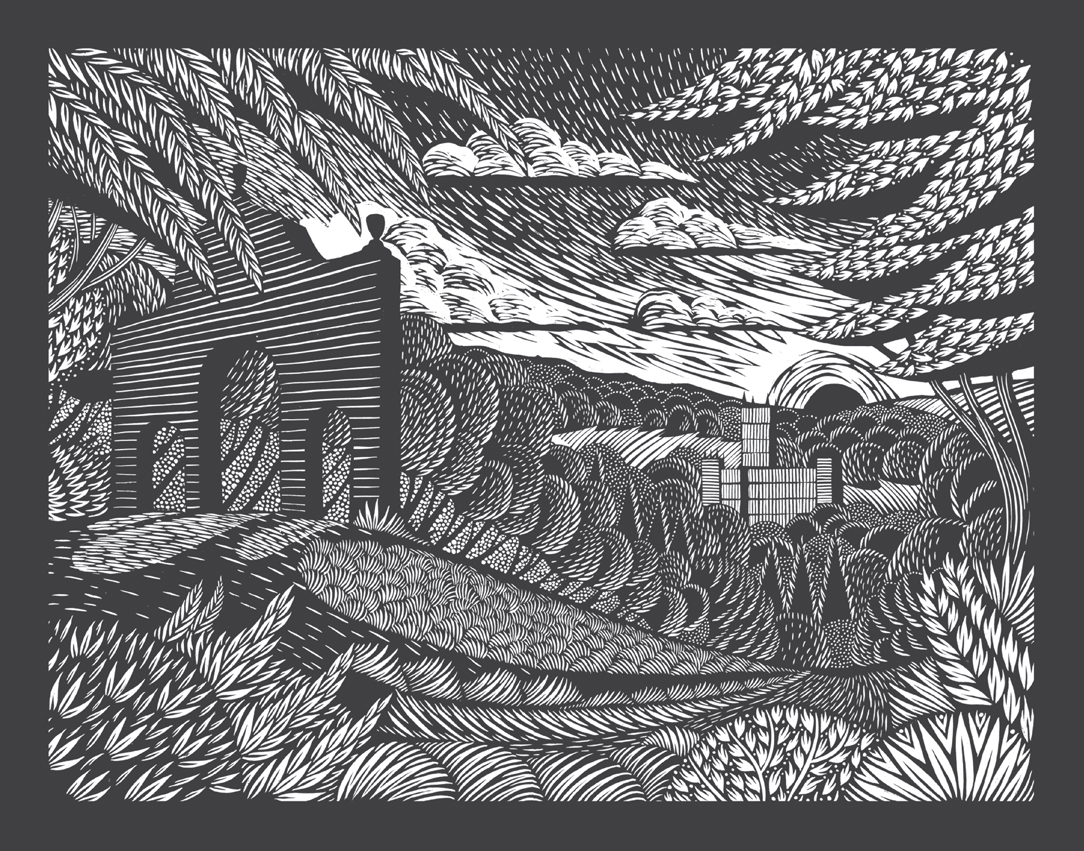

Highclere belongs to the 8th Earl of Carnarvon, George Reginald Oliver Molyneux Herbert. Its 6,500 acres have been in the Carnarvon family for almost 350 years but was first enclosed during medieval times as the official residence for the Bishops of Winchester. When William of Wykeham became bishop in 1366 he created two more deer parks, set up five more fishponds and enclosed the rabbit warrens from the pilfering nets of the local commoners. Confiscated by the Crown, the estate then fell into private hands, and eventually, in 1679, was bought by a wealthy lawyer, Robert Sawyer, the current earl’s ancestor. It is now a classic aristocratic estate, with farmland, forestry, a deer park, pheasant runs and an ornate castle at its heart. But for all its ancient heritage, its solid stone structures, it is a mercurial place, where fact dissolves into fiction, and fiction resolves into fact.

The script of Downton Abbey reflects much of Highclere’s actual history. Both Highclere and Downton were used as a hospital for officers wounded in the First World War. Downton’s earl married an American heiress to inject the estate with her fortune. In real life, the Highclere estate was saved from financial ruin by the 5th Earl’s marriage to Lady Almina, the illegitimate daughter of Alfred de Rothschild of the American banking dynasty. The banker finally paid off his indiscretion with a $200,000 gift to cover the earl’s debts and an $800,000 dowry, much of which the earl took to Egypt to finance the excavation of Tutankhamun’s tomb.

In Season 3, Downton Abbey is shocked by a sudden death in the family, forcing them to pay an enormous death tax which threatens to break up the estate. Similarly, in 1923, when the 5th Earl died suddenly of the curse placed on him by the young Egyptian king (or from sepsis from a shaving cut) the increased estate duty imposed by Lloyd George in 1909 almost broke the Highclere estate in two. They were faced with a tax that today would amount to £30 million and, rather than selling land, the biggest taboo in aristocratic estate management, they managed to dig around in the attic and organised a yard sale at Christie’s, where they sold a few paintings by Gainsborough and Leonardo.

One of the great themes of Downton Abbey is the restrictions and burdens imposed on those with great wealth. Lord Grantham is the paterfamilias and is seen forever wandering the corridors of his castle in a state of pained concern – even when fondling a housemaid in his dressing room, he has a stately anguish to him, constantly exasperated by the bonds of his own innate nobility. On the lord’s shoulders lie not just the prosperity of the present, but the twin weight of his lineage: his ancestors and his heirs. The real Earl of Carnarvon mirrors the sentiment: ‘As Julian Fellowes has said in the Downton script, you don’t want to be the Earl that lets the whole thing down and it all collapses – and that’s the thing that really sort of hangs over one a bit.’

Here at Highclere the fantasy of Downton has seeped through the veil of fiction and hardened into something real. Before the success of the show, Highclere Castle faced £12 million worth of damage restoration, the roofs, the follies, the relentless pressures of the elements on old stone architecture. Luckily for Lord Carnarvon, the writer of Downton sends his kids to the same school as the Carnarvons, and is also one of the club: Julian Fellowes is properly addressed as Lord Fellowes, and even more properly addressed as Baron Fellowes of West Stafford, lord of the manor of Tattershall, Deputy Lieutenant of Dorset. From his head came not only a phenomenally successful TV show, but also a gambit that earns the Highclere estate a reported £1 million per season, and 60,000 tourists a year. Highclere survives on the vision of itself.

The maze of azaleas opens out into long, sloping fields, with large fallen oaks like ossified squids trailing their tentacles across the grass. The fields are bound with low pheasant fences, grids of intersecting wires held taut beneath waist-high wooden struts, a pleasure to climb. We follow the dried ruts of tyre tracks across the fields, following a young fallow deer, which is bolting around trying desperately to find a way through the fences. She leads us up the slope where she butts against the boundary and finally finds some loosely slung barbed wire to scrape through, where she disappears into the beechwoods. The top of the slope is the perimeter of the standard-issue Capability Brown landscaped parkland, those famous Lebanon cedar trees, and there, rising above the treetops, is our first sight of Downton Abbey.

Highclere Castle is the twin of the Houses of Parliament. It has the same Bath stone and decorative ashlar flourishes and was designed by the same architect, Charles Barry, three years into his commission to rebuild the seat of government. Like all the great houses so far in this book, like Badminton, Boughton, Belvoir, Basildon, Charborough, Fonthill and Arundel, its design communicates both classical splendour, the touch of God, and also, very clearly, an aristocratic authority upon the land it controls. Lady Carnarvon talks with fondness of the tourists that come to the estate: ‘They turn up here, and get so excited there’s a real Earl and Countess.’ But what exactly is real about the aristocracy?

On the surface, the aristocracy seems to be a form of cosplay for hereditary landowners, a subculture of adults titillated by their own fancy dress. It is obsessed with fashion. The monarch doesn’t invent new hereditary titles, she ‘fashions’ them; likewise, you are not made a lord, you are ‘styled’. At the queen’s coronation in 1953, the moment the archbishop placed the crown on her head, the dukes, and the dukes alone, were also allowed to put on their hats – their coronets. They were wearing robes with four bands of ermine stitched in diagonals down their front, while, further away, the earls remained hatless, with only three ermine bands on their chest. The earls have coronets, too, and on them they are entitled to eight strawberry leaf motifs and eight silver balls. But this sartorial peacockery is the foliage of a much deeper rooted ideology, one that encapsulates everything from knightly honour codes to the later Victorian regulations of cutlery spacing. In Season 4 of Downton Abbey, Julian Fellowes coins a beautiful phrase to describe it: ‘conforming to the fitness of things’. Vanity Fair, in describing the Downton series, puts it just as neatly: ‘we are whisked into a world that is distinctly based upon the sanctity of the done thing.’ The nobility operates on a system of manners.

The concept of a superior class of human predated William the Conqueror. The Anglo-Saxons had their eorls, ceorls, gesiths and thegns, each elevated above the other in proportion to the land they owned. A set of status regulations from the early eleventh century, the Textus Roffensis, states that if a ceorl prospered and he ‘possessed fully five hides of land of his own, a bell and a castle-gate, a seat and special office in the King’s hall’, then he was entitled to the rights of a thegn.

But when William invaded England, the 4,000 or so thegns were wiped from power and replaced by 180 of William’s closest mercenary allies, the barons. A new hierarchy of French nouns was imposed: the barons, then the viscounts, the marquises and the dukes. The only remaining Germanic title was earl, which was kept to divert the crass minds of the English, and is a lasting legacy that the English were not always so bewitched by their betters. Geoffrey Hughes, Professor of the History of the English Language in Johannesburg, explains: ‘It is a likely speculation that the Norman French title “count” was abandoned in England in favour of the Germanic “earl” … precisely because of the uncomfortable phonetic proximity to cunt.’

The numbers of nobility swelled as successive kings bought new allegiances. The land that now belonged entirely to the Crown was parcelled off and attached to titles that the kings plucked (fashioned) from their heads. When the barons forced King John to sign Magna Carta, they secured more power and autonomy than anyone before them. They had continued in the spirit of the Textus Roffensis, as self-anointed fathers of their flock, and with their church bell and castle gate they offered both spiritual and protective couvert to their tenants. In exchange, they expected a tithe of the land’s produce and military allegiance to their own private army. England became a collection of principalities, like the Roman concept of Latifundia, private estates run by slaves (in England, serfs) that were entirely self-sufficient. Against the king’s orders, some even minted their own currency.

Just as Highclere survives on its own illusion, so the nobility of the Middle Ages based their hierarchies on fairy tales. Chivalry was the governing ideology of French romance literature and when Edward III set up the Order of the Knights of the Garter, he did so to emulate the bedtime stories he had heard of Arthur and his knights. This feedback loop between real and unreal continues to this day: when the queen’s third son married, he was honoured with an earlship and decided to ‘style’ himself Earl of Wessex, a region that no longer exists but that was inspired by his admiration for a character invented by Tom Stoppard for the film Shakespeare in Love.

Amid this make-believe there were some real-life perks. Up until 1949, a peer of the realm could only be tried by a jury of his peers, that is, other peers – no commoner was allowed to pass judgment on his actions. A peer could not be arrested for debt and bankruptcy and, up until 1711, nor could his servants. They alone had the right to sue against slander and, like a special offer coupon cut from junk mail, they got free postage.

We have hopped the fence of the private park and found our way to a road leading past the castle and on to the chapel. William Cobbett galloped through this estate in 1821 and praised it as ‘the prettiest park that I have ever seen. A great variety of hill and dell. The house I did not care about, though it appears to be large enough to hold half a village.’ This is a sly, Cobbetty reference to the village of Highclere which was uprooted and forcibly cleared in 1774 to make way for the earl’s house and private gardens. This old style of power, the landlord as warlord, has waned with the relatively recent fad for human rights. Aristocrats no longer get free postage, and all other real-life privileges have been abolished – but still the aristocracy, like a phantom limb, triggers the nervous system of the English. And still the question remains: what does it all mean?

I found the answer in the bookshop of another aristocratic estate, Hatfield House, the seat of Lord Salisbury. Optimistically titled Democracy Needs Aristocracy, the book was written by Daily Telegraph journalist, and quasi-aristocrat, Peregrine Worsthorne, and is a defence of aristocratic values in the modern age. The book is a masterclass of self-delusion: like a papier-mâché balloon made from wet newspaper, it pastes reams of words around a concept that is nothing more than hot air. But as Andrew Marr says on the front cover: it is compelling.

The key to the aristocracy is in its name. From the Greek άριστος and κράτος, it means ‘rule by the best’ and the twinned concepts are crucial to comprehending the vision. The aristocracy is a governing class that emerged out of military conquest of other nations (including England) and has been deeply embedded in the judicial framework of the land since the Middle Ages. The House of Lords evolved from the king’s closest advisers, the Magnum Concilium, the consigliere to their mob boss. For Worsthorne, the principal justification for their influence on the laws of the land was their experience of managing their own personal fiefdoms. Second to this were the trappings of privilege – by being subjected to the best education they were better suited to high-minded thinking. In the absence of having to work for a living, they were able to spend their days leafing through ancient tracts or walking their estates engaged in blithe philosophical thought. The third justification is a French term: noblesse oblige. The aristocrat is brought up in an atmosphere that makes him profoundly aware of his own social responsibility, both towards his estate and by extension his nation. Worsthorne quotes Viscount de Tocqueville, the nineteenth-century social historian and descendant of Norman nobility: ‘He willingly imposes duties on himself towards the former and the latter, and he will frequently sacrifice his own personal gratifications to those who went before and to those who will come after him.’

This is the reason Lord Grantham paces the corridors of Downton with knitted brow, and the same thing ‘that sort of really hangs’ over the Earl of Carnarvon. Heavy lies the head that wears the coronet. Noblesse oblige is the core concept of the aristocracy, which sees the hereditary lineage of power as its own justification. However, Worsthorne is aware of the dissonance this has with the concept of suffrage:

Most certainly it was not the most democratic way to fashion a governing class. For by linking the widespread desire to acquire local status to the performance of public duties and the upholding of professional values, it almost guaranteed and legitimised the continuation of hierarchy and social inequality. So if equality of access is to be regarded as essential for any morally acceptable system of recruitment into the political elite, this old way definitely does not pass that test. But judged by whether it serves the public interest by producing a regular supply of top rank politicians, public servants and professionals, did it pass that test?

He’s being serious. Worsthorne’s phrase ‘equality of access’ is the bridge between the concepts of privilege of class and rights to the land. He goes on to discuss the philosophy of public schools such as Eton and, just down the road from Highclere, Winchester: ‘They went on being taught to regard the governance of England as their personal responsibility and to believe that if they did not set an example of civilised standards of behaviour, then the country would go to pot … the ethics of public service bred into the marrow of their bones.’

Eton was originally established in 1440 as a charity school to provide free education to seventy poor boys. Its founder Henry VI based it on Winchester School, which was set up by Highclere’s own William of Wykeham fifty years earlier. Again, it was constructed to provide education for seventy poor boys, hand-selected because of their aptitude. Today, fees at Eton are now almost £13,000 per term, and at Winchester £400 more. But with the phrase ‘bred into the marrow of their bones’ the aristocracy suddenly lurches from a quaint daydream to something altogether more chilling. This is eugenics, in top hat and tails.

The aristocratic vision of England is a system of layered supremacy: provided each order defers to its superior tier, England remains in perfect harmony. And just as with the witch trials in Rutland or the slave colonies in Barbados, the deepest roots of this self-deception lie in the pretence of the greater good. Worsthorne speaks of ‘the bonds of mutual sympathy and respect that should naturally exist between rich and poor, governors and governed’ – that devotion of the faithful hound, trotting at his master’s heels at the start of every Downton episode. Subordination to the higher class of person is as essential as it is natural. One of the mechanisms of this system is nostalgia, a harking back to when times were more peaceful, that Grand Olde Englande where people knew their place. Lord Fellowes again: ‘I love that faith in the institutions. And I don’t think we really have that any more. We don’t think our leaders shine in that way.’

But did we ever? This notion of the acquiescent nation is a self-regarding fantasy, a vision in the mirror the aristocracy hold to themselves that blocks from their view the entire landscape of working-class history. And here on the borders of Berkshire and Hampshire, this seems particularly short-sighted.

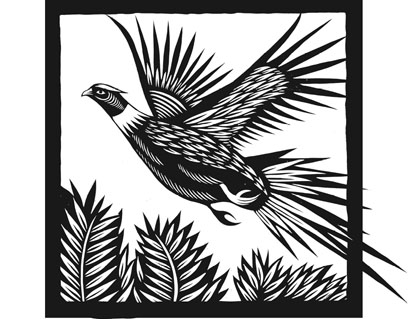

We are trawling our way through long grass beside dark coniferous timber forests and long sweeping cornfields. We pass blue plastic bins raised on stilts, feeders for the pheasants, and wide metal ladders that lead up trees to the sighting perches. The place is teeming with pheasants; they stream along the paths before us and every so often one suddenly flusters out of the bushes like an adulterous duke, escaping the paparazzi with his trousers round his ankles.

The shooting here is about as prestigious as it gets. It’s a social occasion, with luxurious accommodation, grand dinners and a liberal approach to daytime boozing, but its core ethic remains the noisy elimination of pheasants, with each day judged according to the amount of bodies in the bag. A photograph still stands in the Highclere shooting office of King Edward VII who visited the estate in 1904: he shot 1,600 pheasant in just fifteen minutes. But just like the fox of horseback hunting, the pheasant has symbolic meaning. As Harry Hopkins states in his account of the poaching wars in England: ‘The gentry in many parts of England began to look jealously upon their pheasant as the very essence of that property principle upon which the political philosopher John Locke had shown English liberty to be founded.’

The pheasant represented the rights of a landowner because by rearing the birds, and feeding them, they were symbols of the work he put into his estate. But to the commoners, the pheasant represented nothing more than a full belly. As with the fox in the Pierson v. Post case, the pheasant had come to represent a wider battle of property rights, a debate whose fulcrum lay, like trespass, precisely on the line of the fence.

Hunting was the original source of the cult of exclusion. As soon as William the Conqueror forested the lands, the ancient tradition of working-class hunting became redefined as poaching. Simultaneously, the food the working class relied on was redefined as ‘game’, the objects of a moneyed pastime. The Game Acts of the Middle Ages commanded the ‘lawing’ of the peasants’ hunting dogs, the wolfhounds and lurchers. ‘Lawing’ was the term given to chiselling off the front toes of the dog, turning a machine of working-class subsistence into a lame pet. Following the Game Act passed by Richard II, game became the property of the owner of the land. But when Charles II returned to England, resolved to install law and order onto the population that had chopped off his father’s head, he passed another Game Act in 1671 that redefined the ‘qualification’ to hunt. To shoot a pheasant you now had to be an owner of land worth £100 per year, or hold a ninety-nine-year lease on land worth £150. You needed fifty times more land to shoot a pheasant than to vote in local elections.

Property had now developed into what lawyers call a ‘bundle of rights’ – when you bought land, you bought a collection of rights connected to it, the rights to mine its minerals, lop its trees and hunt its game, which were called its ‘perquisites’. Perquisites were the perks of property, the itemised benefits of land ownership, and, because the law had now categorised them as separate entities from the land, they could be sold or rented as individual commodities. By the early seventeenth century, these rights were being leased, as they are today, to City types: merchants, bankers, lawyers and army officers, the squirearchy who would bring down fashionable sporting parties to hunt at the weekends. The majority of tenant farmers who were forbidden by law to shoot a rabbit for their supper now had to watch as the squires came onto the land they worked to kill hundreds of them for sport. But, contrary to Lord Fellowes’ vision of a harmonious England, their resentment was never far from the surface.

By the end of the seventeenth century, the forest wardens of the Middle Ages had mutated into gamekeepers, employed in great numbers as private security guards to patrol their masters’ fences. Poaching had become a quiet, moonlit occupation. Poachers sneaked into estates and with a variety of techniques, netting, coursing, baiting, shooting with crossbows or longbows, they bagged the pheasants in silence. They slid them into deep jacket pockets and took them home, either for the pot or to sell at the local public houses, which had become a marketplace for the black economy.

But at the start of the eighteenth century, fuelled by the civil unrest of commoners across Hampshire and Berkshire, the silence of poaching transformed into a brash, violent protest for equal rights. In broad daylight, hordes of men and women would cross the fences, on horseback or on foot, and devastate the deer stock of local manor parks, taking some home, but leaving, like foxes in the henhouse, most of the carcasses strewn in blood on the plains. Some men wore women’s clothes during the attacks, and because many smudged their faces with charcoal, they were known as ‘the Blacks’.

At long last the aristocracy had what they had always feared: an organised network of sedition. All around Highclere, Enfield Chase, Waltham Chase, Caversham Park, Bagshot Heath, groups of working-class men and women swore oaths of allegiance upon the stag horns of the chimney of the local pubs. They were led by a fictitious character named King John, whose name would underscore the threats and notices they left for the gentry, nailed to the trees of the estates. They branched out from poaching to hijacking and freeing wrongly accused men on the way to the gallows, destroying fishponds, reacting to any breach of their self-construed notion of liberty. When John Trelawney became the Bishop of Winchester in 1707, he began his tenure by auditing his land: he found his woodland coppiced by the commoners, his farms undervalued and his deer stock depleted. When he announced he would restore the ‘Bishopric’s lost rights’, sixteen Blacks invaded the episcopal deer park at Farnham, took three deer and left behind several carcasses – including that of a keeper.

In a justice system dominated by the power of property, where the right to vote was restricted to those with property, where the right to represent was determined by property, where the justice establishments, from the common courts right up to the House of Lords, were governed by men of property, the Blacks were fighting fire with fire. They brought their own philosophy of ownership, the shared rights of the commons, up against the aristocratic, hereditary cult of exclusion, which had reified these rights into the sources of personal profit. Both sides were willing to kill for their rights. But while the Blacks used longbows, the aristocrats used the law.

The Black Act of 1723 introduced fifty new capital offences across the land. For though they were concentrated in only two counties, the Blacks were labelled a national emergency. The land they invaded was owned by royalty and prominent members of the Whig government and, as such, their protests were judged not just as a threat to private hereditary landowners, but to the order of the nation. They were described as Jacobites, terrorist cells seeking to topple the king. The Act was supposed to be a temporary measure, but lasted for another century: the law had stepped resolutely over the fence to defend the interests of a tiny elite over the majority of people outside the enclosure. And there it has stayed.

We have come out of the pheasant rides onto a tarmac road. A ruined folly stands at the foot of a steep wooded slope and to our left are fields of scattered sheep, the tops of trees and the turrets of Highclere. We begin climbing the slope, heading diagonally across the steep hill to the tree line when we hear the low engine of a 4x4 approaching. The cover of the woods is only fifty yards away so we scramble, running on all fours up the hill, to enter the woods and sit, hearts thumping, as the truck rolls by. We continue up through the woods and come to a crest of chest-high feathery grass, glowing gold in the sun. A path has been mown through the long grass and, as we progress up it, we see the triangle pinnacle of Highclere’s most imposing folly: Heaven’s Gate, another of Capability Brown’s concoctions. Either side of us the pheasants rustle the undergrowth, occasionally and needlessly exploding into the air with wild, terrified eyes.

The three-storey brick folly, a large arch with two smaller flanking arches, and two urns either side of its pediment, emerges through the tops of the trees. We walk towards it, stand beneath it and turn to survey the view. From our toes to the horizon, Hampshire is laid out before us, a sea of woodland with the castle deep at its centre. The air is light and crisp. The sky is pinky peach; the sun has just set. We breathe deeply from the climb, inhaling the peace of the scene, drinking in its calm. I am reminded of philosopher Edmund Burke’s definition of the aristocracy:

To be bred in a place of estimation; to see nothing low and sordid from one’s infancy … to stand upon such elevated ground as to be enabled to take a large view of the widespread and infinitely diversified combinations of men and affairs in a large society; to have leisure to read, to reflect, to converse; to be enabled to draw on the attention of the wise and learned, wherever they are to be found … these are the circumstances of men that form what I call a natural aristocracy, without which there is no nation.

Beneath the arches of Heaven’s Gate, bathed in soft light, this is the aristocracy’s vision of England: glorious and empty. To the west and east of the estate, we can see the roads choked with traffic, the lower orders crawling home from work. They are the modern-day descendants of the communities that were cleared from the land, the commoners forced from self-subsistence into the workhouse. They are reminders of the other side of the aristocratic myth, the black inverse of the Downton masthead: the classification of the lower orders that reaches its most extreme bigotry in the myth of the undeserving poor.

Those who share the aristocratic empty workless day are labelled not aesthetes, but idle benefit scroungers, who bleed England of its wealth. It is a fiction as old as enclosure and stands, like its walls, to this day. In 2012 the former Archbishop of Canterbury, Lord Carey, described the welfare system as: ‘an industry of gargantuan proportions which is fuelling those very vices [Want, Disease, Ignorance, Squalor and Idleness] and impoverishing us all. In the worst-case scenario it traps people into dependency and rewards fecklessness and irresponsibility.’

The land beneath me is what England’s welfare system used to look like. With its old community-based customs, it offered a winter fuel allowance and food banks without the stigma of social shame. When these lands were enclosed, self-subsistence was criminalised into poaching, and common ground, like the welfare state today, was presented as a nursery of idleness. The words of an Elizabethan surveyor in Rockingham, just before the outbreak of the Midland Revolt, echo Lord Carey’s sentiments, and predate them by half a millennium: ‘So long as they may be permitted to live in such idleness upon their stock of cattle they will bend themselves to no kind of labour.’

‘You must work for a living,’ proclaim the nobility (from the chaise longue). In the Middle Ages, under a French concept of dérogeance the nobility were actively punished, demoted, for taking part in any kind of labour, and the idea that work dirtied one’s day, which was better spent in contemplation, or sport, lasted well into the nineteenth century. As they avoided work, they also compulsively avoided tax, as John Wade wrote in 1820, in an exposé of the aristocracy called the Black Book, Or, Corruption Unmasked: ‘Instead of bearing the burthen of taxation, which in fact is the original tenure on which they acquired their territorial possessions, have laid it on the people.’

The aristocracy have always lobbied hard against taxation, from demanding lower window tax to actively stifling progressive taxation on the nation. When Chancellor Lloyd George presented the People’s Budget of 1909, with the stated intent of redistributing wealth through the nation, the House of Lords bucked 200 years of tradition and blocked it. The Liberals had sought, for the first time, to introduce a tax on the value of the land. They reasoned that, so long after enclosure, it was too late to redistribute the actual plots of land, but that they could instead redistribute the wealth that had been enclosed with it; as their official pamphlet that began the campaign stated, this was ‘the best use of the land in the interests of the community’. The initial proposal for the tax represented just 0.3 per cent of the total tax burden, but for the Lords it was a trespass on the cult of exclusion, a step too far. They rejected the budget by 350 votes to 75.

Today, many large country houses, including Highclere, have negotiated tax deals with HMRC, swapping hidden inheritance tax breaks for limited, or ‘reasonable’, rights of access to the land they stole. It is unfortunate for HMRC that their arrangement with Highclere even reads like a deal with the devil: Unique ID: 666 details the arrangement between the tax office and the castle, including the opening of Path 3, between Easter and the end of August, from the Wayfarers Walk up to Heaven’s Gate. The public are granted access, but the taxpayer foots the bill. On top of this, aristocrats, like many other landowners, have registered their land to businesses based offshore: today, Lord Salisbury has 2,000 acres of his land in Hatfield registered in Jersey-based companies.

But still the aura of magnificence wreaths their world. And sitting beneath the folly, on Lord Carnarvon’s hill, the magic trick is unveiled. In a study of the landscape architecture of Capability Brown, John Phibbs uses Heaven’s Gate as an example of what he calls ‘transumption’. This is the effect of magical architecture: to infiltrate one site with the aura of another, to be Greece, or Rome, or Heaven itself, and yet still to be in Hampshire. ‘Brown’s early work can create this dream-like state of dissociation, his park wall confining not just deer but a vision, like a precious gas, more dense around the house, and steadily diffusing as it spreads, but likely to burn off against the touch of reality.’

These follies, the sculpted parkland, the crate-imported pheasants, the near-empty houses, are props in theatre sets constructed to create the aura of natural supremacy. Downton Abbey, with all its awards and fine acting, is another perfumed spritz of precious gas that sedates the nation into acquiescence. The aristocrats who tread the boards of this stage, dressed in costumes of ermine, enact a pantomime drama based on a fairy tale. As the nineteenth-century essayist Walter Bagehot said in support of the monarchy: ‘Its mystery is its life. We must not let in daylight upon magic.’ Decorative pomp and verbose flummery is all that disguises the bare basics of the aristocratic wealth system – land enclosed, resources monopolised and rights of use sold back to those that can afford them. Let the daylight in on the magic, and you have nothing but basic rentier capitalism.

Today, a third of Britain is still owned by the aristocracy. The twenty-four remaining non-royal dukes own almost four million acres between them. There are 191 earls, 115 viscounts and 435 barons, and most are still significant landowners. In 2016 the fourteen marquises received just over £3.5 million worth of farm subsidies for their 100,000 acres while seventeen of the dukes who received farm subsidies got £8.4 million between them. Unlike the welfare benefits to those most in need, these farm subsidies are neither means-tested nor capped. Today the perquisites of land ownership have multiplied from basic rent of rights into tax avoidance and subsidies from the state. The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) costs UK taxpayers around £3.8 billion per year and, with these subsidies linked to the number of acres owned, it is often the richest landowners who receive the largest benefits. The writer and activist George Monbiot suggests that the reason these benefits are considered more acceptable than the welfare benefits given to the poorest of our community is because, ‘After being brutally evicted from the land through centuries of enclosure, we have learned not to go there – even in our minds. To engage in this question feels like trespass, though we have handed over so much of our money that we could have bought all the land in Britain several times over.’

Travelling in England after the First World War, the German bishop Dr Dibelius wrote: ‘the English gentleman will always rule because he has captured the soul of the people.’ But this is precious gas. It was never the soul of the people he had captured but simply the value of their land.

We’re sitting in the Packhorse Inn, just north of Hebden Bridge in Yorkshire. There’s a dark moor outside, a full moon shining through the window, a coal fire in the hearth and I’m telling my friend the story of the Rufford Park poachers, the folk song that starts this chapter.

All among the gorse to settle scores

These forty gathered stones

To make a fight for poor men’s rights

And break those keepers’ bones.

In 1851, a group of forty men trespassed onto Rufford Park estate, 18,500 acres of Nottinghamshire owned by John Lumley-Savile, 8th Earl of Scarbrough. The estate was so large it incorporated thirteen parishes and thousands of villagers, none of whom were able to hunt anywhere in the vicinity. From the large number in their group, it’s safe to assume they were not there for poaching, but for payback: they went looking for a fight. Ten keepers blocked their path. There was a violent battle, during which one of the keepers had his skull shattered and died. Four of the ringleaders were arrested, tried and transported overseas for fourteen years’ hard labour.

By the middle of the eighteenth century, the Blacks had all been hanged or transported. But over the following century the violence of working-class protest and the urgency of their predicament only intensified. Between 1750 and 1860, over 4,000 individual applications of enclosure were passed by government and, according to historian J. M. Neeson, this accounted for a third of the English agricultural land now in private hands. In 1773, a year before the village of Highclere was cleared by Lord Carnarvon, George III had passed a new enclosure act that simultaneously hastened the procedure of enclosure and criminalised the rights of commoners. In 1811, the Luddites had begun smashing up the new automated looms, in 1815 there were riots against the new Corn Laws, four years later came the Peterloo Massacre and, in 1830, the Swing Riots were spreading across the south and east of England, with groups of men and women scuppering the threshing machines that had stolen their jobs. It was not just enclosure being protested, but its effects – the mechanisation of industry, the monopoly of the corn trade, the funnelling of the working class into factories and workhouses, the hollowing of the countryside, the decimation of community.

Since the sixteenth century, the earls of Scarbrough were also in possession of much of Calderdale, which by the nineteenth century included the moor outside the Packhorse Inn. By this time, the aristocracy had been swamped by a new breed of landowner, the mercantile classes, the parvenus, whose industry and colonial trade had amassed them fortunes to rival the old families of England. The moor outside the Packhorse Inn, Walshaw Moor, managed to keep its noble bloodline unblemished until 2002, when it was bought by a local retail tycoon called Richard Bannister. Three years later, he bought the adjoining Lancashire Moor, establishing his sole domain over 16,000 acres of the Calder Valley. He immediately set about improving the land, upping the yield of grouse from 100 brace to 3,000, industrialising the land as he had done the trouser industry. In doing so, Walshaw Moor became the new centre of an ancient debate: how should land be used, and whose decision is it?

It’s closing time, and suddenly we’re out in the cold car park, facing the moor. It is vast and dark. We feel as if we’re standing on the shore of an ocean. We stock up on extra layers, cheese sandwiches and whisky, lock the car, hope very much we’ll see it again and head out.

Every year, thirty-five million partridge and pheasant are released into the estates of England, twice the biomass of the nation’s wild birds. Of those, Defra estimate that half are bred like factory-farmed chickens, trapped in colony cages of about sixty to eighty birds, giving them less room than a sheet of A4 paper. While basic welfare regulations exist for farmed birds, they do not apply to any bird reared for ‘use in competitions, shows, cultural or sporting events or activities’. Pheasant shooting is the English equivalent of the South African ‘canned shooting’ where big game is kept in cages until the day of the hunt, when it staggers out into the plains to be shot by big-barrelled money men. Pheasants are decorative supermarket chickens slaughtered by firing squad.

Grouse shooting, however, is billed as the ‘Formula One of game sports’, drenched in adrenaline and machismo. It’s wild. The red grouse is native to the uplands, used to the weather, and goes like shit off a shovel. In flight the grouse can reach speeds of 70mph: they fly low and turn fast, and because they offer the best shooting they are hailed as the king of gamebirds. But their wildness is a fantasy.

The record for the most grouse bagged in a single day is 2,929 birds; they were shot in 1915 on the Abbeystead estate, now owned by the Duke of Grosvenor. More typically, in the present day, you might expect to bring down between 75 and 150 brace (a duo of grouse) from a day’s shooting. As with pheasants, a good grouse moor is judged by the quantity of corpses in the bag. As such, these wild and remote lands have become a production line for live quarry. England has just 15 per cent of the total landmass of Britain devoted to grouse shooting, but still manages to account for almost half of the 450,000 grouse exterminated each year. So, since the Victorian age, the rough heather of the moors has become home to a host of intensive farming techniques, designed to improve its yield.

The grouse are bred in such numbers that their colonies are vulnerable to infection: parasites in their gut often wipe out swathes of the population, so the moors are littered with birdfeeders containing grey pellets of levamisole hydrochloride, a short-term fix that lasts forty-eight hours. Other estates prefer a more direct approach and keepers drive onto the moor at nights, daze the birds in powerful spotlights, net them and force the medication down their throats with syringes.

We have entered the moor through an old iron gate that has the same haunted-house atmosphere as the gates in the first shot of Citizen Kane, with the slow pan over the ‘No Trespassing’ signs. But for the last two decades the spell of trespass has been lifted from these moors. Since the Countryside Rights of Way Act of 2000, all moorland in England has been opened to a right of access. You cannot camp here, but you can walk wherever and whenever you like. But our right to roam was only one of the common rights that was extinguished by enclosure. For when the fences went up around common land, commoners lost not only their access but their rights to contribute to a collective decision on how it was used.

The wind is like thunder up here and bullies us relentlessly. We veer for cover and cut off the tarmac path, heading up a steep path of green cut between the heather. Our feet bounce on the ground making our steps elastic and exaggerated, as if we haven’t quite found our sea legs. We are walking on a specific formation of sphagnum moss known as blanket bog, layers of hairy green sponge that have felted into peat beneath the surface. A third of all grouse moors in England, about 250,000 acres, is covered in this rarest of habitats, which is protected by the highest level of stewardship in the EU. Professor Joseph Holden, an expert in peat bogs, states: ‘In the UK we have 13 per cent of the world’s blanket bogs. Globally, peatlands are more important than tropical rainforest in terms of taking carbon out of the atmosphere.’

These bogs have blanketed the moors since the end of the Ice Age, when the trees there had been cleared for grazing by Bronze Age settlers. Over millennia they have absorbed the carbon in the atmosphere, which now lies densely packed beneath our feet in ‘carbon sinks’. However, every year, these moors are systematically burned to increase the yield of new green shoots on the heather. Grouse can eat up to 50 grams of heather shoots a day, and to keep up with the prodigious productivity of these moors the growth of heather must be maximised in its efficiency. But the burning destroys the sphagnum moss and dries out the peat, turning the carbon sinks into a carbon source: the damage done to these peatlands in England releases 260,000 tonnes of carbon back into the atmosphere every year, the equivalent emissions of 88,000 average-sized saloon cars.

The government’s environmental agency Natural England first launched a case against Richard Bannister and Walshaw Moor in 2010. Burning this rare eco habitat is somehow still perfectly legal, but Natural England judged Bannister’s ‘improvements’ to be far more extensive than was permitted by their previous Notice of Consent to Lord Savile. They sought to modify the Notice of Consent and simultaneously launched a case against him for his adaptations to the moor. It wasn’t just the burning. In total there were forty-three listed claims, mainly referring to damage done to the wildlife by installing illegal infrastructure – gripping (digging drainage), and the installation of five new car parks and five new tracks, to better facilitate Mr Bannister’s guests as they are driven around the moors. This is called moorland management.

Walshaw Moor fought back. Richard Bannister sent Natural England a claim for £31.8 million compensation if the modification order was found to be unjust. He was supported by the Moorland Association, a pin-striped iteration of the Knights of the Garter, who were anxious that this might serve as a test case for the other areas of blanket bog that cover grouse moors: it was a threat to productivity. Selections of their lobbying emails and details of their dinners with the then Defra under-secretary MP Richard Benyon were published in Mark Avery’s book Inglorious: ‘Suggestions of readdressing the basis of existing agri-environmental schemes and whether heather burning should be allowed on blanket bog and wet heath has the potential to destroy two thirds of heather moorland in England and with it, all the mammoth economic and environmental benefits!!’

Then, out of nowhere, Natural England dropped its claim against Walshaw Moor. Before the scientific evidence had been presented, they settled out of court with Walshaw Estates Ltd. Over a period of the next ten years, the taxpayer will now pay Richard Bannister a total of £2.5 million to keep to agreements that we know nothing about. This is called higher level stewardship.

All around us, the moor seethes and bristles with wind. The sky is overcast, but the wind is so strong it moves the cloud like smoke from a burning stack – it lathers over the moon, masking and revealing it so that down below the earth flashes and strobes and seems to surge like the heavy swell of the ocean. We find a broad slab of rock and clamber up onto it to sit like shipwreck survivors, floating on the swaying wrath of heather. The air is thick with moisture, beading on our jackets, and beneath us the moor is a sea of woven roots, thatched tendrils and spongy wet woollen moss that is laden with water. The whole landscape heaves with hydraulic power.

George Winn-Darley is the head contact for the North York Moors sector of the Moorland Association. He inherited a 7,000-acre grouse moor in 1986 and is as integrated into the powerful cabal of land ownership as a man might be. He has sat on Defra’s Best Practice Burning Group, was chairman and vice-chairman of the CLA’s (Country Landowners’ Association) Yorkshire branch, and is currently trustee/director of Yorkshire Esk Rivers Trust – we met him before in chapter two kicking a hunt saboteur in the chest. He has declared moors to be ‘the only unsubsidised upland land use on offer’. It is unclear what he means by unsubsidised. In 2014, then chancellor George Osborne raised the subsidy given to moorland by 84 per cent, from £30 per hectare to £56, while, two years earlier, the total annual subsidies awarded to land used for grouse shooting was £17.3 million. Winn-Darley goes on to say:

It’s all dependent on the moors’ amazing attraction to men with money. Rich men have always fallen in love with them, be they nineteenth century industrialists or modern City types. They bring their wealth to these wild places and it trickles down the valleys like rain, supporting jobs in hotels, garages and helping keep the culture of the moorlands alive.

Grouse shooting is presented by the lobby groups as the only commercially viable means of maintaining a grouse moor, a rhetorical hall of mirrors, which is like saying golf is the only way of keeping a golf course running. This is the old Tudor justification of land improvement, the idea that by privatising land you can better serve the community through the increased production and distribution of wealth. It trickles down from on high.

But Hebden Bridge sees very little of the wealth of the Walshaw estate. Richard Bannister doesn’t charge for shooting, but keeps his moor for friends and business associates. They are wined, dined and boarded at the lodge on the estate and, other than the seven full-time keepers, day rates for beaters and a bit of diesel at the petrol station, it’s hard to see where the wealth is distributed, not to mention what value the taxpayer receives from its subsidies. Here in Hebden, what descends from the moors is not money but rain, and it doesn’t trickle, it gushes. In the last twenty years, Hebden has been engulfed in six serious floods. On Boxing Day 2015, more than 3,000 homes were flooded: cars were submerged, people evacuated by helicopter and rescuers kayaked down the streets.

The residents of Hebden link the floods to the management of the moors above them. The Moorland Association disagree, claiming to be ‘fully engaged with doing all that can be done through consensus and innovation to help flood alleviation, but even with every inch restored to active blanket bog (which may or may not be possible and will take a long time), the help this will add to the needed suite of flood mitigation in the North of England is limited’.

No one rejects the notion that burning the bog reduces its capability to hold water, but the arguments flare over how much it affects the scale of the flooding. A 2016 study found a direct correlation between the burning of blanket bogs and an increase in the peak flow of water down in Hebden. Any arrangement of burn patches on Walshaw increased the peak flow by 2.5–5 per cent, enough to tip the surge over the floodgates. Rather than limiting the burning, the findings of this study showed that all burning should be categorically banned.

In 2016 Walshaw Moor Ltd resumed its burning. Damages paid to the residents for flood repair totalled about a fifth of the money promised to Richard Bannister in the out-of-court settlement for his Higher Stewardship of the moor. A further £8 million of taxpayers’ money has been allocated to build defences across the Calder Valley, building walls that protect the houses of Hebden from flooding, and obscure Mr Bannister’s role in its cause.

The community at Hebden Bridge has been fighting the moor for years. When Mark Avery’s petition to ban grouse hunting reached 100,000 signatures, forcing a debate in Parliament, the single largest area of signatures came from Hebden. They have set up a community group called ‘Ban the Burn’, which has taken its complaints direct to the EU to launch another case against Walshaw Moor, for burning land protected under their directives. And they are not just fighting, they are planting. Twenty-five years ago they launched a group called ‘Treesponsibility’, initially a pub-table group to discuss concerns about the environment. In the following two decades, its members began to focus on tree planting in the area, a direct move to thwart climate change and to mitigate the effects of flooding. Hundreds of people gather to plant twelve acres of woodland every year, binding the ground with roots to intercept the rainwater, and connecting the community in activities that have visible outcomes.

Yet no matter how hard they campaign, and how many trees they plant, they are constantly thwarted by the cult of exclusion and its central hallucination: dominion. The laws of property pretend that whatever lies within the fence line is entirely unconnected to the land and communities outside it, as if ecology can be partitioned with a neat line. Floodwater doesn’t obey these legal fictions. Nor does the wind that in the early nineteenth century carried the pollution from the coal-burning Lancashire mills and dropped it, as acid rain, on the uplands of Calderdale, scouring it into bare peatland. Like the communities in Hampshire and Berkshire, fenced off from the wealth of the land, the community of Hebden is directly affected by the total dominion of the property owners. And like the community of Hebden, the entire global community is affected by the burning of peat and the release of carbon into the atmosphere.

The British taxpayer finances this destruction to enable the pastime of a select few. Avery estimates that the 147 moors across England, which occupy over half a million acres, are used by just 5,000 individuals – under 0.01 per cent of the population. The law defends the rights of the few over the many, by right of property alone.

It’s about four in the morning. The lights of Hebden are bleeding from the horizon into new swathes of fog that seem to be spreading our way. Sitting on our lifeboat rock, we’ve grown cold. We creak to our feet and jump around for a bit, and, though we’re exhausted from the ceaseless battering of the wind, we press on. There is a ruined farmhouse on the highest point of this moor that the guidebooks claim was inspiration for Heathcliff’s house in Wuthering Heights, and a path of stone slabs laid by Lord Savile’s men to take us there.

The path winds us east towards the edge of the moor. The hills are not steep, but the buffeting wind and the roll of the valley instil a weird sense of vertigo, like being up in the eaves of a theatre, with the roof blown off. Far beneath us, we can see the streetlights of Oxenhope and Haworth, and we imagine the villagers asleep in their beds, the silence blanketing their streets. The whole land is dreaming.

For centuries, England has been lulled by the aristocratic myth that land is better off in the hands of men-who-know-better and, even more spuriously, that its value belongs only to those that own it. Just as the fence lines of property pretend that the surrounding community is not affected by the management techniques within, they also create the illusion that the value of the land is unconnected to the community around it. The opposite is true.

While a landowner can improve the property, or capital, on their land, by building new and better houses, the value of the land itself (on average, 70 per cent of its total price) is only increased in direct correlation to the services provided by the community that surrounds it. Land banking proves this. When a property firm buys land as an asset, they hold it as it accrues in value. The buddleia takes root, the place is fly-tipped and the owners do nothing to increase its worth. Instead, they wait, while improvements in infrastructure (the roads, rail links and hospitals financed by the taxpayer) and the value of local amenities (the theatres, bars, shops and mechanics’ yards) do the work for them. Society generates the value of the land.

When the Liberals proposed their Land Value Tax in 1909, they sought to separate the value of the property (its capital) from the value of the land beneath it. They reasoned that because land values are financial reflections of the interconnectedness of society, they should belong to the communities that have created them. For this reason, Land Value Tax, or Site Valuation Tax, is seen by some not even as a tax at all, but simply the recovery of the economic rent owed to the community that created its value. The idea that landowners should pay a tax to the community that has generated the wealth they enjoy is such an inversion of the accepted orthodoxy that it has always been presented as an upheaval of the order of the land. But it is nothing more than waking out of the spell that has bound the land for so long. Let the daylight in on the magic and the paradigm of private property inverts: the landlords pay a rent to the people.

Top Withens is everything a gothic farm cottage should be. Built into the bank of the moor, in the shade of two trees, it is roofless, squat and ruined. It’s Brontë-bleak. But it also has a sense of humour: attached to the wall, engraved in stone, knowing full well how far visitors have walked to reach it, is a sign that tells us it’s all make-believe: ‘The buildings, even when complete, bore no resemblance to the house she described but the situation may have been in her mind when she wrote of the moorland setting of the heights.’

Well, thanks for your honesty. As we sit and eat our sandwiches, my mind is stuck on Heaven’s Gate at Highclere: another architectural illusion celebrating another famous fiction, the heavenly splendour of the aristocratic class. Like the folly, the illusion is crumbling. Either side of the earls of Carnarvon, the parvenus are encroaching on the aristocracy. To the west, Stowell Park, a 5,500-acre estate, belongs to the Vesteys who made their money through beef. And to the east is Sydmonton estate, whose 400 years of noble bloodline was cut short in 1978, when it was bought by musical impresario Andrew Lloyd Webber. In 2010, just before the Downton cash cow, Lloyd Webber offered to buy Highclere Castle, to alleviate the earl of the cost of upkeep. The Carnarvons refused his offer, quoted in the Daily Telegraph: ‘We are not selling up to some rich man.’ Ouch. It seems that the earl has been intoxicated by his own precious gas, bewitched by the idea that his class distinguishes him from any other type of landowner. But as historian David Cannadine says, class has always been an illusion: ‘classes never actually existed as recognisable historical phenomena, still less as the prime motor of historical change. They were nothing more than rhetorical constructions, the inner imaginative worlds of everyman and everywoman, seeking as best they could to explain their social universe to themselves.’

The myth of the aristocracy is that they were ever anything more than rent collectors. All old money was new money at some point. The motto of Lord Salisbury, commissioned when he was styled an earl in 1605, is sero sed serio, late but serious. When he was given his lands, he was well aware he was the parvenu, and now 500 years in, he’s taken off the plastic wrapping and become part of the furniture.

Professor of Law Joel Bakan describes the modern-day corporation in words that could equally apply to the aristocratic family. ‘The corporation’s legally defined mandate is to pursue, relentlessly and without exception, its own self-interest, regardless of the often harmful consequences it might cause to others.’ The similarities between corporations and aristocratic families are prevalent. Aristocratic escutcheons, their shields and mottos, are early prototypes of corporate brands and slogans. The noble lineages, sustained by primogeniture and biased tax relief, employ the same techniques of trusts and offshore estates used by corporations to keep the taxman away. Noblesse oblige is no more than paternalism dressed in tinsel: the idea that the elite have a better sense of the world than their lessers. The chivalric codes of chevisance, largesse and valiance have mutated into the modern corporate jargon: environmental stewardship, land management, estate conservation, best practice, engagement, innovation, progress.

The aristocrats of England made their money by monopolising the land and using their elite definition of property rights to line their own pockets. Whenever they have been in need of money, they have suspended their ‘higher stewardship’ of the land and squeezed it until the coins came out. To raise money for the repair of Highclere Castle, the earl applied for planning permission to build new houses on forty acres of the estate. While the locals called it ecological vandalism, the aristocracy call it ‘Enabling Development’, a loophole in planning legislation that allows for development, otherwise viewed as harmful, if it pays for restoration of heritage assets. In Downton Abbey, when the Granthams are faced with their huge inheritance bill, the dowager countess exclaims: ‘The point is, have we overlooked something, some source of revenue, previously untapped … if only we had some coal, or gravel, or tin!’

To this day, if it’s not gold, coal, oil or silver, if you own the mineral rights you can hollow the land of its resources and pocket the value. The Dukes of Norfolk and Rutland mined the land they owned in Sheffield for its iron ore, likewise the Dukes of Buccleuch, Hamilton and Portland. A hundred years after the Rufford Park poachers, Lord Savile leased the manor of Ollerton to a coal-mining company. The surrounding area is still known as the Dukeries, because of the enormous swathes of land (around 88,000 acres) in Nottingham that were owned by just four men, the Dukes of Norfolk, Portland, Kingston and Newcastle – they, too, enclosed the land, and leased it to mining companies, transferring its wealth from the people that once used the common lands, into their own pockets.

Mining was just one means of extracting wealth from the land. Enclosure was the means of extracting this wealth from society. Land as a resource is naturally scarce; as Mark Twain said, ‘they’re not making it any more’. To enclose the land is to monopolise its value, to privatise community wealth, a process summed up by geographer David Harvey with the phrase ‘accumulation by dispossession’. In land, private wealth comes only at the expense of the public treasury.

When taxpayers’ money finances infrastructure projects such as Crossrail or HS2, money is taken out of the common purse to provide infrastructure for all to use. However, when the value of the land around these new stations increases dramatically, under the current laws of property it goes directly to the property owner. The extension of the Jubilee underground line in London cost the taxpayer £3.4 billion. Eleven stations were added to the line, increasing the connectivity of these sites and raising the value of the land. An independent survey estimated the increase in value of land 1,000 yards from each station to have been £13 billion, all of which went into the hands of landowners, who contributed nothing to its gain. A Land Value Tax could have entirely paid for the new infrastructure and left the communities affected by the new line significantly better off.

In the era of the Blacks and the Rufford Park poachers, the wealth of the land was expressed by a buck or a doe, a pheasant or a hare. Today, wild animals are no longer the currency of a common treasury; tax represents the value of the land that, in the words of the Rufford Park poacher, should be ‘quite equal for to share’. Since 1995, land values in this country have risen by 412 per cent, with land now accounting for over 50 per cent of the wealth of the UK. But, under the current laws of property, the nation sees none of it.

The fence lines around private property are the dotted lines around the map that say cut-out-and-keep to any owner, blue-blooded or otherwise. Gradually, year by year, England is beginning to recognise the systematic draining of resources and wealth that occurred in colonial exploitation, when Englishmen took the wealth of foreign nations and claimed it as their own. But we are still a long way from recognising the deeper truth: that it was practised first on their own soil, when the landlords colonised the commons.

As moneyed men drew lines around common land and swallowed up its resources, their fences redefined the purpose of the land: what was acceptable within it and who had rights to it. As more and more of the land was enclosed, the cult of exclusion came to define not just local land, but extended across the country as a whole. They defined the nation.