Chapter 18

The 4-Step Basic Approach

To earn your highest possible score on the Reading test, you need an efficient and strategic approach to working the passages. In this chapter, we’ll teach you how to work the passages, questions, and answers.

HOW TO CRACK THE READING TEST

The most efficient way to boost your Reading score is to pick your order of the passages and apply our 4-Step Basic Approach to the passages. Use the Basic Approach to enhance your reading skills and train them for specific use on the ACT.

The 4-Step Basic Approach

Step 1: Preview. Check the blurb and map the questions.

Step 2: Work the Passage. Spend 2–3 minutes reading the passage.

Step 3: Work the Questions. Use your POOD to find Now, Later, and Never Questions.

Step 4: Work the Answers. Use POE.

Before we train you on each step in cracking the test the right way, let’s talk about the temptations to attack the passages in the wrong way.

This Isn’t School

In the Introduction, we discussed the reading skills you’ve spent your whole school career developing. You have been rewarded for your ability to develop a thorough, thoughtful grasp of the meaning and significance of the text. But in school, you have the benefit of time, not to mention the aid of your teachers’ lectures, class discussions, and various tools to help you not only understand but also remember what you’ve read. You have none of those tools on the Reading test, but you walk into it with the instinct to approach the Reading test as if you do.

Where does that leave you on the ACT Reading test? You spend several minutes reading the passage, trying to understand the details and follow the author’s main point. You furiously underline what you think may be important points that will be tested later in the questions. And when you hit a particularly confusing chunk of detailed text, what do you do? You read it again. And again. You worry you can’t move on until you have solved this one detail. All the while, time is slipping by….

Now, onto the questions. Your first mistake is to do them in order. But as we told you in the Introduction, they are not in order of difficulty, nor chronologically. You confront main-idea questions before specific questions. You try to answer the questions all from memory. After all, you’ve spent so much time reading the passage, you don’t have the time to go back to find or even confirm an answer. And when you do occasionally go back to read a specific part of the passage, you still don’t see the answer. So you read the chunk of the passage again and again.

If you approach the Reading test this way, you will likely not earn the points you need to hit your goal score.

The Passage

You don’t earn points from reading the passage. You earn points from answering the questions correctly. And you have no idea what the questions will ask. You’re searching desperately through the passage, looking for conclusions and main points. You stumble on the details, rereading several times to master them. But how do you even know what details are important if you haven’t seen the questions?

The Questions

When you answer the questions from memory, you will either face answer choices that all seem right, or you will fall right into ACT’s trap, choosing an answer choice that sounds right with some familiar words, but which in reality doesn’t match what the passage said.

The test writers at ACT know everyone is inclined to attack the Reading test this way. They write deceptive answer choices that will tempt you because that’s what wrong answers have to do. If the right answer were surrounded by three ridiculous, obviously wrong answers, everyone would get a 36. Wrong answers have to sound temptingly right, and the easiest way to do that is to use noticeable terms out of the passage. You gratefully latch onto them the way a drowning person clutches a life preserver.

THE 4-STEP BASIC APPROACH

The best way to beat the ACT system is to use a different one. The 4-Step Basic Approach will help you direct the bulk of your time to where you earn points, on the questions and answers. When you read the passage, you’ll read knowing exactly what you’re looking for.

Step 1: Preview

The first step involves two parts. First, check the blurb at the beginning of the passage to see if it offers any additional information. Ninety-nine percent of the time, all it will offer will be the title, author, copyright date, and publisher. There is even no guarantee that the title will convey the topic. But occasionally, the blurb will define an unfamiliar term, place a setting, or identify a character.

Passage III

HUMANITIES: This passage is adapted from the article “The Sculpture Revolution” by Michael Michalski (©1998 Geer Publishing).

True to form, this offers only the basic information.

The real value in Step 1 comes in the work you do with the questions.

Map the Questions

Take no more than 30 seconds to map the questions. Underline the lead words. Star any line or paragraph references.

Lead Words

We introduced lead words in the Introduction. These are the specific words and phrases that you will find in the passage. They are not the boilerplate language of reading test questions like “main idea” or “author’s purpose.” They are usually nouns, phrases, or verbs.

Map the following questions that accompany the humanities passage. Even if a question has a line/paragraph reference, underline any lead words in the question.

21. The author expresses the idea that:

22. The information in lines 75–81 suggests that Quentin Bell believes that historians and critics:

23. Which of the following most accurately summarizes how the passage characterizes subjectivism’s effect on Rodin?

24. According to the passage, academicism and mannerism:

25. Information in the fourth paragraph (lines 33–41) makes clear that the author believes that:

26. According to the passage, Renoir differs from Daleur in that:

27. According to the passage, Cézanne’s work is characterized by:

28. Based on information in the sixth paragraph (lines 49–57), the author implies that:

29. In line 65, when the author uses the phrase “modern,” he most nearly means sculpture that:

30. Which of the following statements would the author most likely agree with?

Your mapped questions should look like this:

21. The author expresses the idea that:

22. The information in lines 75–81 suggests that Quentin Bell believes that historians and critics:

22. The information in lines 75–81 suggests that Quentin Bell believes that historians and critics:

23. Which of the following most accurately summarizes how the passage characterizes subjectivism’s effect on Rodin?

24. According to the passage, academicism and mannerism:

25. Information in the fourth paragraph (lines 33–41) makes clear that the author believes that:

25. Information in the fourth paragraph (lines 33–41) makes clear that the author believes that:

26. According to the passage, Renoir differs from Daleur in that:

27. According to the passage, Cézanne’s work is characterized by:

28. TBased on information in the sixth paragraph (lines 49–57), the author implies that:

28. TBased on information in the sixth paragraph (lines 49–57), the author implies that:

29. TIn line 65, when the author uses the phrase “modern” he most nearly means sculpture that:

29. TIn line 65, when the author uses the phrase “modern” he most nearly means sculpture that:

30. Which of the following statements would the author most likely agree with?

Two Birds, One Stone

Mapping the questions provides two key benefits. First, you’ve just identified (with stars) four questions that have easy-to-find answers. With all those great lead words, you have two more questions whose answers will be easy to find. Second, you have the main idea of the passage before you’ve read it. When you read the passage knowing what to look for, you read actively.

Look again at all the words you’ve underlined. They tell you what the passage will be about: modern sculpture, Renoir, Daleur, Cézanne, Rodin, and a bunch of “-isms” that you could safely guess concern art. There is also someone named Quentin Bell, historians, critics, and art. You’re ready to move on to Step 2.

Read Actively

Reading actively means knowing in advance what you’re going to read. You have the important details to look for, and you won’t waste time on details that never appear in a question. Reading passively means walking into a dark cave, wandering in the dark trying to see what dangers or treasures await. Reading actively means walking into the cave with a flashlight and a map, looking for what you know is in there.

Step 2: Work the Passage

Your next step is to work the passage. Spend no more than 2–3 minutes. Look for and underline the lead words, underlining each time any appear more than once.

You’re not reading to understand every word and detail. You’ll read smaller selections in depth when you work the questions. If you can’t finish in three minutes, don’t worry about it. We’ll discuss time management strategies later in the chapter.

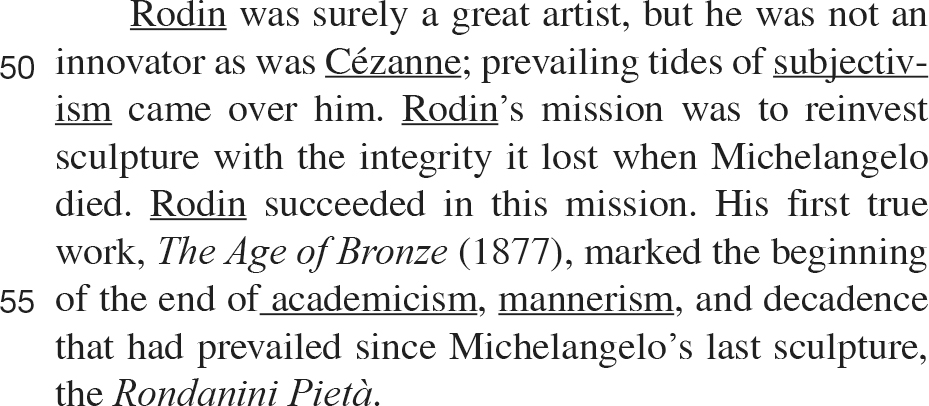

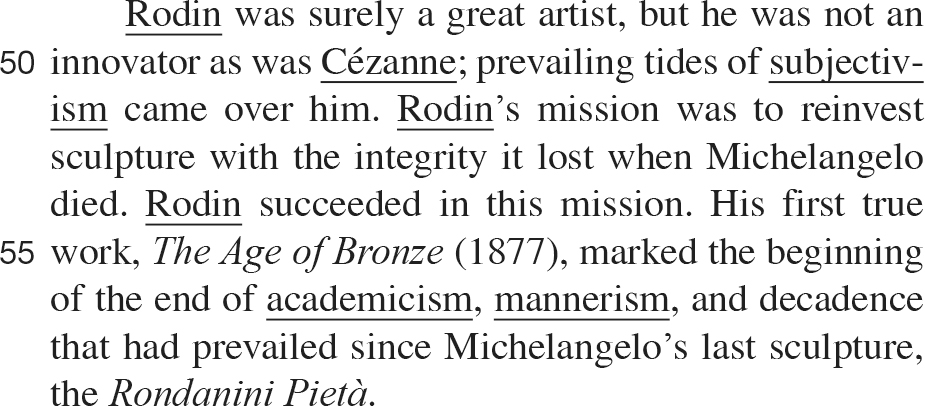

Passage III

HUMANITIES: This passage is adapted from the article “The Sculpture Revolution” by Michael Michalski (©1998 Geer Publishing).

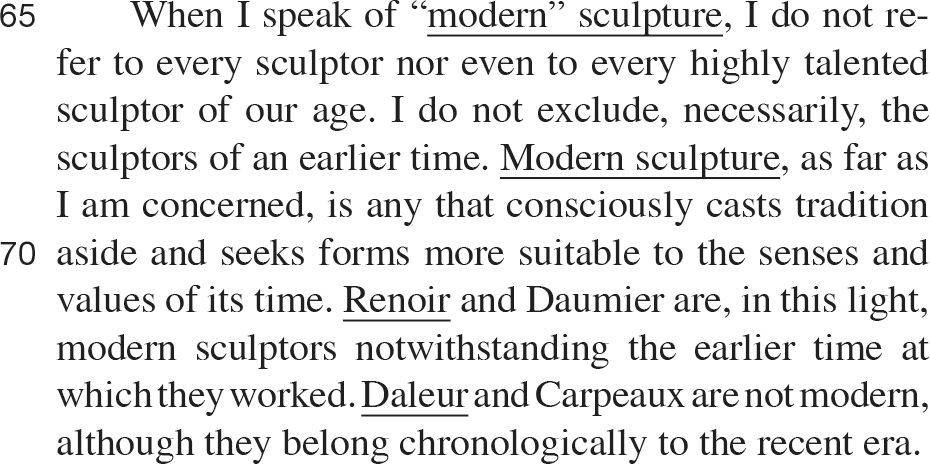

Your passage should look like this. If you couldn’t find all the lead words to underline, don’t worry. You can do those questions Later. But did you notice that there is nothing underlined in the second and third paragraphs? If you hadn’t mapped the questions first, you would have likely wasted a lot of time on details that ACT doesn’t seem to care about.

Passage III

HUMANITIES: This passage is adapted from the article “The Sculpture Revolution” by Michael Michalski (©1998 Geer Publishing).

Step 3: Work the Questions

As we told you in the Introduction, you can’t do the questions in the order ACT gives you. Question 21 has no stars or lead words and poses what seems to be a Reasoning question. Thus, it’s neither easy to answer, nor is the answer easy to find. Question 22 is a great question to start with, however. It has a star, and it’s a Referral question, asking directly what is stated in the passage.

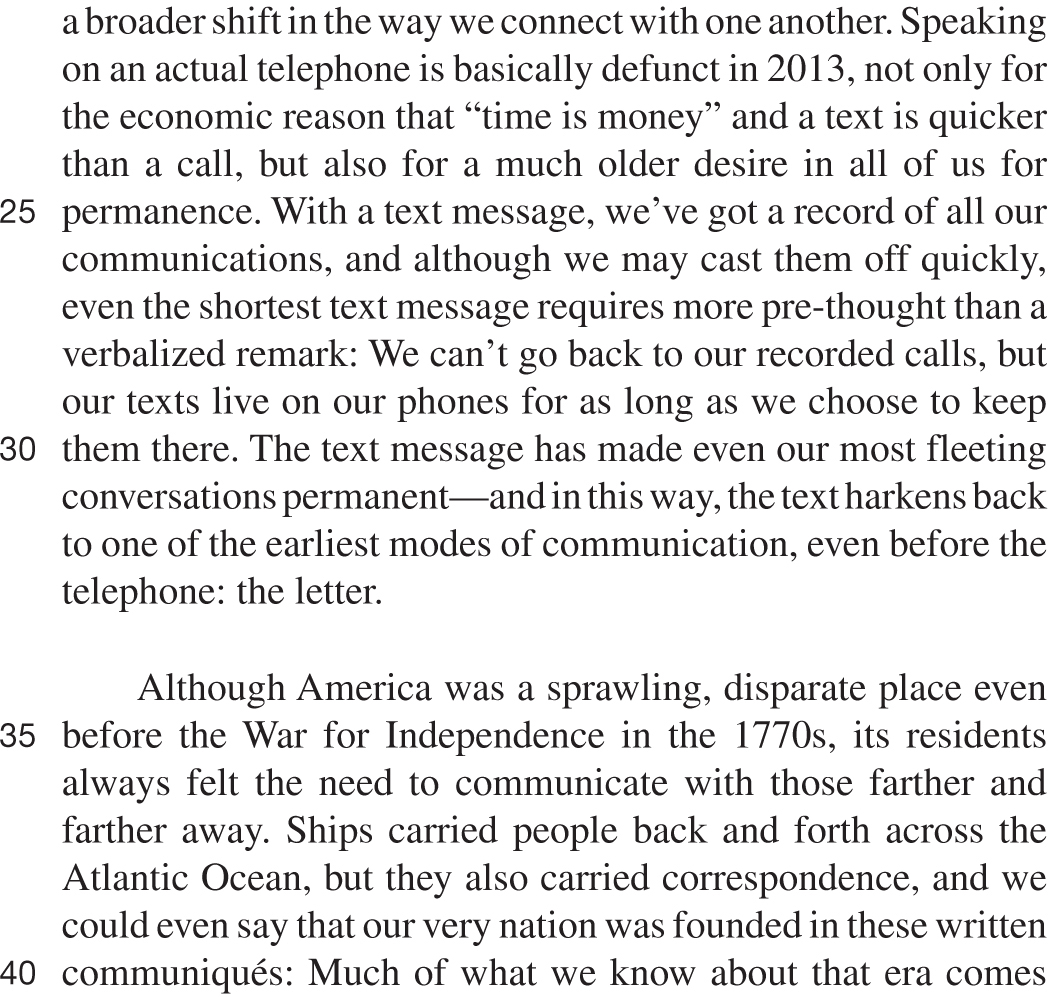

22. The information in lines 75–81 suggests that Quentin Bell believes that historians and critics:

22. The information in lines 75–81 suggests that Quentin Bell believes that historians and critics:

Here’s How to Crack It

Make sure you understand what the question is asking. Now read what you need out of the passage to find the answer. The line reference points you to line 75, but you’ll find your answer within a window of 5–10 lines of the line references. Read the last paragraph to see what Quentin Bell thinks about historians and critics.

Work the Questions

-

Pick your order of questions. Do Now questions that are easy to answer, easy to find the answer, or best of all, both.

-

Read the question to understand what it’s asking.

-

Read what you need in the passage to find your answer. In general, read a window of 5–10 lines.

Step 4: Work the Answers

Do you see the importance of making sure you understand the question? We care here what Quentin Bell thinks about historians and critics, not what the author thinks of them. But the question is a Referral question, asking what is directly stated. Lines 75–78 offer Bell’s opinion. Now find the match in the answers.

Work the Answers

-

If you can clearly identify the answer in the passage, look for its match among the answers.

-

If you aren’t sure if an answer is right or wrong, leave it. You’ll either find one better or three worse.

-

Cross off any choice that talks about something not found in your window.

-

If you’re down to two, choose key words in the answer choices. See if you can locate them back in the passage, and determine if the answer choice matches what the passage says.

Here’s How to Crack It

F. have no appreciation for the value of modern art.

Bell is critical of historians and critics, and value could refer to significance in the passage. This seems possible, so keep it.

G. abuse art and its history.

The passage states that the term is abused, not art and its history. This is a trap, and it’s wrong. Cross it off.

H. should evaluate works of art on the basis of their merit without regard to the artist’s fame.

There was nothing in the window about “fame.” Cross it off.

J. attach the phrase “modern art” to those sculptors that intrigue them.

Attach the phrase is a good match for name as ‘modern’ and sculptors that intrigue them is a good match for in whom they happen to be interested. This answer is better than (F), and it is correct.

Steps 3 and 4: Repeat

Look for all the Now questions, and repeat Steps 3 and 4. Make sure you understand what the question is asking. Read what you need to find your answer, usually a window of 5–10 lines. Work the answers, using POE until you find your answer.

Referral Questions

Referral questions are easy to answer because they ask what was directly stated in the passage. Read the question carefully to identify what it’s asking. The passage directly states something about what? Once you find your window to read, read to find the answer. The correct answers to Referral questions are barely paraphrased and will match the text very closely.

How to Spot Referral Questions

-

Questions that begin with According to the passage

-

Questions that ask what the passage or author states

-

Questions with short answers

If the answer to a Referral question is also easy to find, they are great Now questions. Look for Referral questions with line references or great lead words.

26. According to the passage, Renoir differs from Daleur in that:

F. Daleur had no inspiration, while Renoir was tremendously inspired.

G. Renoir’s work was highly innovative, while Daleur’s was not.

H. Daleur was a sculptor, while Renoir was not.

J. Renoir revered tradition, while Daleur did not.

Here’s How to Crack It

Renoir and Daleur are great lead words, easy for your eye to spot in the eighth paragraph. On the real test, you’ll have the passage on the left and all your mapped questions on the right page. For convenience’s sake and to avoid flipping back to the passage, we’re printing the window to read with the question.

Lines 71–73 state that Renoir was a modern sculptor and Daleur is not. But that same sentence mentions four artists in this light. What light? Any time you see this, that, or such in front of a noun, back up to read the first mention of that topic. This light is the author’s definition of modern, given on lines 68–71.

Now work the answers. Cross off answers that don’t state Renoir is modern and Daleur is not. Innovative in (G) is a good match for modern and is the correct answer. Inspiration in (F) doesn’t match modern. Choice (H) is disproven by the passage. Choice (J) tempts with tradition but compare it to the text, and the author states modern sculpture consciously casts tradition aside.

Try another Referral question with great lead words.

27. According to the passage, Cézanne’s work is characterized by:

A. a return to subjectivism.

B. a pointless search for form.

C. excessively personal expressions.

D. rejection of the impressionistic philosophy.

Here’s How to Crack It

Cézanne appears first in the fourth paragraph, but the question is about Cézanne’s work, which is in the fifth paragraph. Choice (D) matches reaction against impressionism and is the correct answer.

Reasoning Questions

Reasoning questions require you to read between the lines. Instead of being directly stated, the correct answer is implied or suggested. In other words, look for the larger point that the author is making.

Reasoning questions aren’t as easy to answer as Referral questions, but they’re not that much harder. If they come with a line or paragraph reference or a great lead word, they should be done Now.

How to Spot Reasoning Questions

-

Questions that use infer, means, suggests, or implies

-

Questions that ask about the purpose or function of part or all of the passage

-

Questions that ask what the author or a person written about in the passage would agree or disagree with

-

Questions that ask you to characterize or describe all or parts of the passage

-

Questions with long answers

25. Information in the fourth paragraph (lines 33–41) makes clear that the author believes that:

25. Information in the fourth paragraph (lines 33–41) makes clear that the author believes that:

A. Rodin was more innovative than Cézanne.

B. Cézanne was more innovative than Rodin.

C. Modern art is more important than classical art.

D. Cézanne tried to emulate impressionism.

Here’s How to Crack It

The question doesn’t provide specific clues what to look for and instead asks what the author’s point is in the fourth paragraph. The author is comparing the artists Cézanne and Rodin. The concluding sentence states that Cézanne…had a more lasting effect on sculpture than did Rodin. Choice (A) says the opposite. The paragraph does not mention either classical art or impressionism, so (C) and (D) can be eliminated. Choice (B) is a good paraphrase of the author’s point and is the correct answer.

Work Now the Reasoning questions with line or paragraph references or great lead words. Use POE heavily as you work the answers.

28. Based on information in the sixth paragraph (lines 49–57), the author implies that:

28. Based on information in the sixth paragraph (lines 49–57), the author implies that:

F. mannerism reflects a lack of integrity.

G. Rodin disliked the work of Michelangelo.

H. Rodin embraced the notion of decadence.

J. Rodin’s work represented a shift in style different from the works of artists who preceded him.

Here’s How to Crack It

Use POE. Choices (F) and (H) use terms from the paragraph but garbles them. Rodin wanted to restore elements of sculpture that had changed since the death of Michelangelo, which means he respected Michelangelo’s work, so (G) is not supported. The last sentence states that Rodin’s work marked the beginning of the end and therefore represented something new, as is stated in (J), which is the correct answer.

29. In line 65, when the author uses the phrase “

modern

,” he most nearly means

sculpture

that:

29. In line 65, when the author uses the phrase “

modern

,” he most nearly means

sculpture

that:

A. postdates the Rondanini Pietà.

B. is not significantly tied to work that comes before it.

C. shows no artistic merit.

D. genuinely interests contemporary critics.

Here’s How to Crack It

Use POE. The Rondanini Pietà is in the wrong window, so eliminate (A). Choice (B) is a good paraphrase of the art that consciously casts tradition aside and seeks forms more suitable to the sense and values of its time, and it is the correct answer. Choice (C) can’t be proven by the passage; the author doesn’t state that they have no worth at all. Choice (D) tempts with contemporary as a possible match for modern or its time, but critics are not in this window.

Later Questions

Once you have worked all the questions with line or paragraph references and great lead words, move to the Later questions. The answers to questions without a line or paragraph reference or any great lead words can be difficult to find, which is why you should do them Later. But the later you do them, the easier they become. You’ve either found them or you’ve narrowed down where to look. From the windows you’ve read closely to answer all the Now questions, you may have located lead words you missed when you worked the passage. And if you haven’t, then they must be in the few paragraphs you haven’t read since you worked the passage.

24. According to the passage, academicism and mannerism :

F. were readily visible in The Age of Bronze.

G. were partially manifest in the Rondanini Pietà.

H. were styles that Rodin believed lacked integrity.

J. were styles that Rodin wanted to restore into fashion.

Here’s How to Crack It

According to the passage means that this is a Referral question and should be easy to answer. The challenge, however, is finding the lead words. But you read this paragraph when you answered 28. Not only would you find academicism and mannerism if you missed them when you worked the passage, but you also know the paragraph well from working question 28. Use POE to eliminate choices that don’t match your correct answer from 28. Choices (F), (G), and (J) all contradict both the passage and your previous answer. Choice (H) matches, and it is the correct answer.

Now move onto question 23. Because you worked it Later, the answer is easy to find.

23. Which of the following most accurately summarizes how the passage characterizes subjectivism’s effect on Rodin?

A. It ended his affiliation with mannerism.

B. It caused him to lose his artistic integrity.

C. It limited his ability to innovate.

D. It caused him to become decadent.

Here’s How to Crack It

You know this paragraph well by now, but subjectivism didn’t play a major role in the points made for questions 28 and 24. Use POE to eliminate (B) and (D) because they don’t match what you’ve learned about Rodin. You know Rodin didn’t like mannerism, but check the part of the window that specifically discusses subjectivism. Lines 49–51 give subjectivism as the explanation of why Rodin was not an innovator. That matches (C) perfectly.

Last

Questions 24 and 23 showed how your work on each question builds your understanding of the passage, making the Later questions easier to do than if you hadn’t waited. The questions, after all, refer back to the same passage, so the answers should agree with each other. Some questions may ask about a relatively minor detail in the passage, but most should ask about important details, the ones that help the author make the main point.

Use what you’ve learned about the passage to answer last the questions that ask about the entire passage.

21. The author expresses the idea that:

A. art should never be studied in terms of movements.

B. art can be labeled as modern when it introduces a style that is different from those found in works that came earlier.

C. lesser artists do not usually vary their styles.

D. great artists are always nonconformists.

Here’s How to Crack It

Question 29 helps the most with this question, but several questions echoed the theme of art making a break from the past. The correct answer is (B).

30. Which of the following statements would the author most likely agree with?

F. Cézanne had greater influence on modern sculpture than did Rodin.

G. Rodin made no significant contribution to modern sculpture.

H. Daumier should not be considered a modern sculptor.

J. Carpeaux should be considered a modern sculptor.

Here’s How to Crack It

Questions 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, and 28 all help eliminate the wrong answers (G), (H), and (J), making (F) the correct answer.

THE 4-STEP BASIC APPROACH

Try a passage on your own. Give yourself up to 12 minutes, but don’t worry if you go a little over. Use the passage on the next page to help you master the Basic Approach, and worry less about your speed. Later in the chapter and in the next, we’ll discuss other strategies to help with time. The answers are given on the page following the passage.

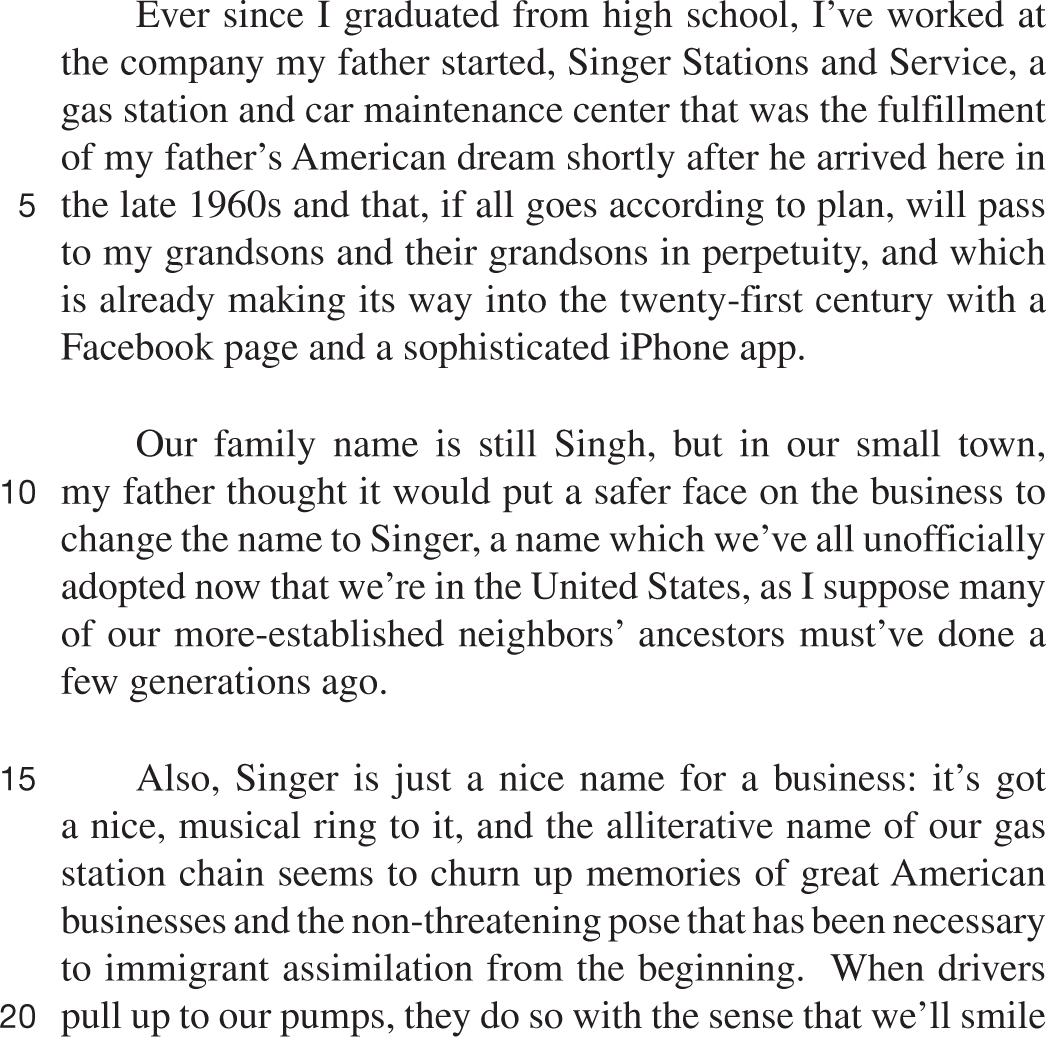

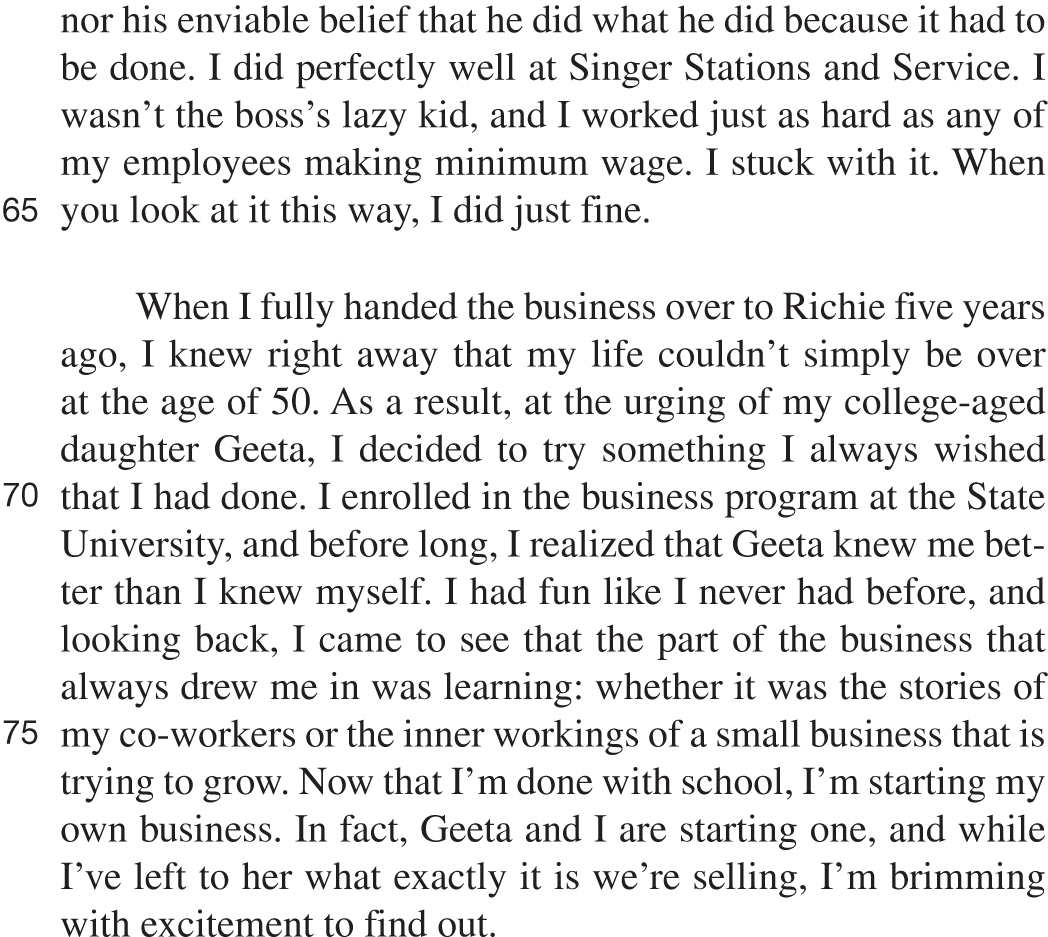

Passage I

PROSE FICTION: This passage is adapted from the novel Skyward by Prakriti Basrai (©2012 by Prakriti Basrai).

1. The passage can be best described as primarily:

A. one business owner’s questioning of the direction his business has taken after he handed the management over to his son.

B. a son’s elegant praise of his father’s skill and determination in creating a family business.

C. a personal narrative that describes one man’s role within a business started by his father and passed down through generations.

D. a story of the changes in American immigrant businesses in the twentieth century.

2. Which of the following actions affecting the family business does the narrator NOT attribute to his father?

F. A sophisticated iPhone app

G. The founding of Singer Stations and Service

H. A change in the family’s last name

J. An alliterative name for the business

3. The narrator explicitly declines to take a firm stand on which of the following issues?

A. The personal preferences he had that enabled him to succeed in business

B. The quality of the name Singer Stations and Service

C. Which generation has had the most difficult time in the world of business

D. Whether the family should have kept the name Singh rather than Singer

4. According to the passage, what is the narrator’s father’s attitude toward words?

F. He treats them like a poet would.

G. He believes business names should be alliterative.

H. A man should keep his mouth closed and his ears open.

J. He believes that advertisers work in the business of deception.

5. As it is used in line 40, the word hurt most nearly means:

A. impede success.

B. injure.

C. sting.

D. cause a bruise.

6. What or who is the “saving grace” referred to in the passage?

F. Singer Stations and Service

G. The narrator’s mother

H. The narrator’s daughter

J. Religious piety

7. What does the narrator state is his mother’s view of his role in Singer Stations and Service?

A. In actuality, the credit for the business’s name should go to him because he was the real artist.

B. He had the worst time of any of his family members because he ran a business in which he did not have a passionate interest.

C. His hard work, though less public than his son’s, was crucial to the company’s success at the time.

D. He should be more grateful for his inheritance and not insist on changing professions.

8. According to the passage, who or what is “Raman (The Gas Man)”?

F. Singer’s main gas supplier

G. The business’s main competitor

H. The narrator’s son

J. The narrator’s father

9. According to the passage, the narrator’s daughter knows the narrator better than he knows himself because:

A. the company’s new Internet presence emerged after he retired.

B. she suggested that he go back to school, and he enjoyed doing so.

C. Richie bought a second Italian sports car.

D. the history of Singer Stations and Service is a history of the immigrant experience.

10. As it is used in line 73, the phrase came to see most nearly means:

F. arrived at.

G. realized.

H. attended.

J. visited.

Score and Analyze Your Performance

The correct answers are (C), (F), (C), (F), (A), (J), (B), (J), (B), and (G). (For detailed explanations, see Chapter 25.) How did you do? Were you able to finish in 12 minutes or less? If you struggled with time, identify what step took up the most time. Identify any questions that slowed you down. Did you make good choices of Now and Later questions? Did you use enough time? If you finished in less than 12 minutes but missed several questions, next time plan to slow down to give yourself enough time to evaluate the answers carefully. In Chapter 19, we’ll work on skills to help you work the questions and answers with more speed and greater accuracy. But first, we’ll finish this chapter with strategies to help you increase your speed working the passage.

BEAT THE CLOCK

When you struggle with time, there are several places within the Basic Approach that are eating up the minutes.

Pacing the Basic Approach

If you spend 10–11 minutes on your first passage, use your time wisely.

Step 1: Preview. 30–60 seconds

Step 2: Work the Passage. 3 minutes

Steps 3 and 4: Work the Questions and Answers. 7 minutes

Step 1: Preview

To move at the fastest speed when you preview, you can’t read the questions. Let your eye look for lead words and numbers. Don’t let your brain read.

Time yourself to see if you can preview the following questions and blurb in less than a minute.

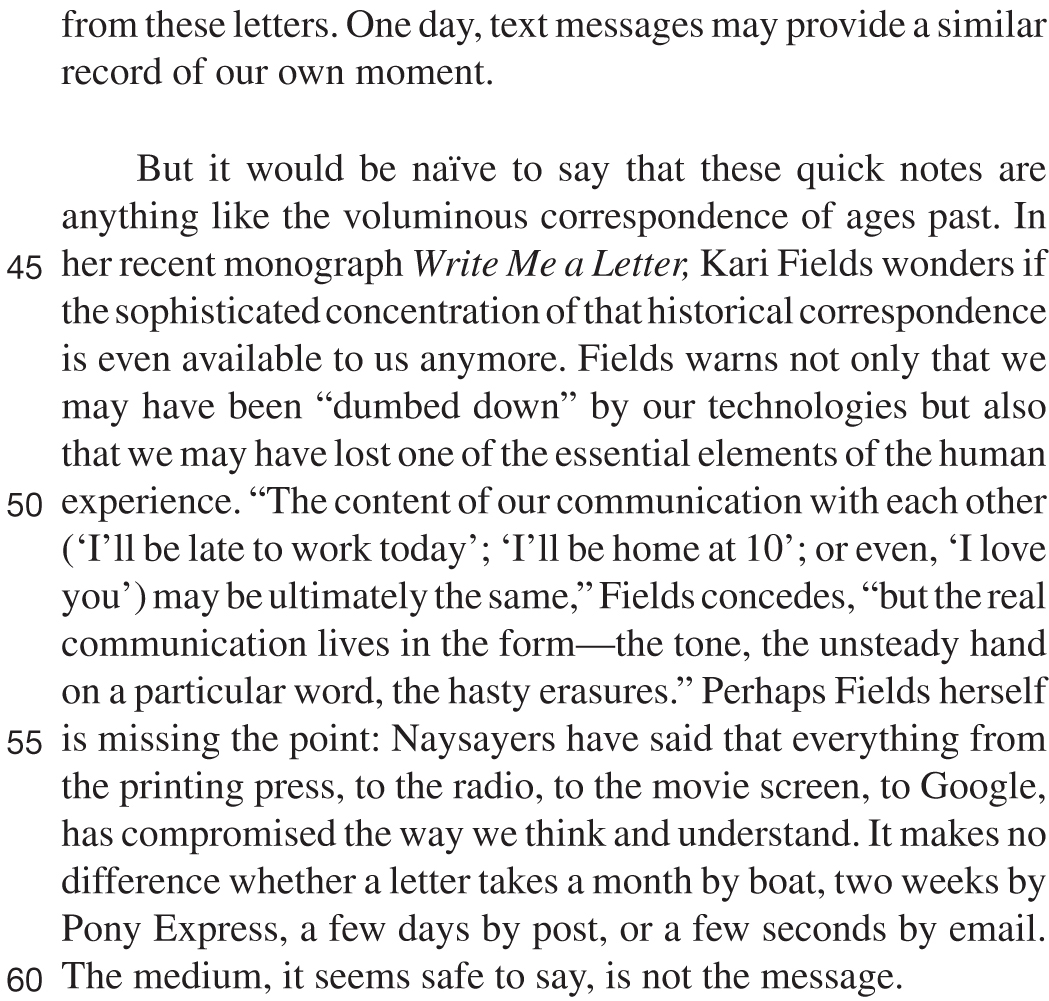

Passage IV

NATURAL SCIENCE: This passage is adapted from the article “What Giotto Saw” by James Herndon (©2001 by Galaxy Press).

31. The author characterizes the comparison of the work of Sagdeev to that of Peale as:

32. The main point of the last paragraph (lines 43-48) is to show that Zdenek Sekanina:

33. In terms of their role in studying the rotational period, the 1920 photographs are described by the author as:

34. Lines 17–19 mainly emphasize what quality?

35. According to the passage, the nuclear surface of Halley’s comet is believed to be:

36. As described in the passage, Giotto’s camera was specifically programmed to:

37. As used in the passage, the word resolution (line 11) means:

38. The passage indicates that H. Use Keler:

39. Lines 25–28 are best summarized as describing a problem that:

40. According to the passage, the volume of Halley’s comet is:

Step 2: Work the Passage

This step should take no more than 3 minutes, and you should not be trying to read the passage thoroughly. Your only goal is to find as many of your lead words as you can and underline them.

Skimming, Scanning, and Reading

If we told you to skim the passage, would you know what that means? If you do, great. If you don’t, don’t worry. Skimming is something many readers feel they’re supposed to do on a timed test, but they don’t know what it means and therefore can’t do it.

Reading needs your brain on full power. You’re reading words, and your brain is processing what they mean and drawing conclusions. Reading is watching the road, searching for directional signs, and glancing at the scenery, all for the purpose of trying to figure out where the road is leading.

Skimming means reading only a few words. When you work the passage, your brain can try to process key parts that build to the main idea, but you don’t necessarily need to identify the main idea just yet. Working the questions and answers tells you the main idea and all the important details. Skimming is reading only the directional signs and ignoring the scenery.

Scanning needs very little of your brain. Use your eyes. Look, don’t think, and don’t try to process for understanding. Scanning is looking for Volkswagen Beetles in a game of Slug Bug.

When you’re working the passage, you can skim or scan, but you shouldn’t be reading. Read windows of text when you work the questions.

If you feel you can’t turn your brain off when you work the passage, or you even skim and scan too slowly, then focus only on the first sentence of each paragraph. You may find fewer lead words, but you will give yourself more time to spend on working the questions and answers and can find the lead words then.

Time yourself to work the following passage, focusing only on the first sentence of each paragraph. We’ve actually made it impossible to do otherwise. Look for the lead words you underlined in Step 1 and underline any that you see.

Let’s see what you learned in less than three minutes.

Now Questions

You should have several Now questions.

-

Questions 32, 34, 37, and 39 all have line references.

-

Questions 31, 33, 35, 36, 38, and 40 all have lead words, great lead words in some.

-

The lead words in 31 can be found in the first sentence of the sixth paragraph.

-

The lead words in 33 can be found in the first sentence of the last paragraph.

-

The lead words in 35 and 36 can be found in the first sentence of the first paragraph.

-

The lead words in 40 can be found in the first sentence of the fifth paragraph.

-

Nine of the ten questions have been located, and the great lead word in 38 should be easy to find easy to find when you’re given the whole passage and not a lot of “blahs.”

The Pencil Trick

When you have to look harder for a lead word, use your pencil to sweep each and every line from beginning to end. This will keep your brain from reading and let your eye look for the word.

The Passage

You also have a great outline of the passage. The topic sentences have drawn a map of the passage organization, and the transition words tell you how the paragraphs connect.

-

What is the first paragraph about? The nucleus of Halley’s Comet and the Giotto camera.

-

The second paragraph? The details that the photographs show.

-

The third? What scientists have learned from the photographs.

-

How does the fourth paragraph relate to the third? On the other hand tells you that it is different from the third.

-

How does the fifth paragraph relate to the fourth? Moreover tells you that they are similar.

-

What is the sixth paragraph about? It’s still on volume, which came up in the fifth paragraph.

-

What is the last paragraph? It’s the conclusion, which the transition word Finally makes clear.

Topic Sentences and Transition Words

Think of your own papers that you write for school. What does a good topic sentence do? It provides at worst an introduction to the paragraph and at best a summary of the paragraph’s main idea. What follows are the details that clarify or prove the main idea. And do you care about the details at Step 2? No, you’ll focus on the details if and when there is a question on them.

Transition words are like great road signs. They show you the route, direct you to a detour, and get you back on the path of the main idea. When you skim, you’re focusing on topic sentences and transition words.

Look for Transition Words

Here are 15 transition words and/or phrases.

-

Despite

-

However

-

In spite of

-

Nonetheless

-

On the other hand

-

But

-

Rather

-

Yet

-

Ironically

-

Notwithstanding

-

Unfortunately

-

On the contrary

-

Therefore

-

Hence

-

Consequently

In the next chapter, we’ll cover more strategies for working the questions and answers. But now it’s time to try another passage.

Reading Drill 1

Use the Basic Approach on the following passage. Time yourself to complete in 8–10 minutes. Check your answers in Chapter 25.

Passage III

HUMANITIES: This passage is adapted from the article “The Buzz in Our Pockets” by Danielle Panizzi (©2013 by Telephony Biquarterly).

1. The main idea of the passage is that:

A. telephone conversations are defunct because they are so impermanent.

B. telephones took the place of serious long-letter writing.

C. text messages do not provide real interactions for the people who send them.

D. text messaging is a popular medium whose social effects are debatable.

2. Based on the passage, with which of the following statements would Fields most likely agree?

F. The frequent use of text messaging can limit people’s other human experiences.

G. Internet users lost their capacity for human experience when they started using Google.

H. Text messages provide a quick, intimate way for people to communicate.

J. Text messages force people to write more thoughtfully to one another.

3. How does the passage’s author directly support her claim that the text message is more than a simple message?

A. By citing examples from American culture in which text messaging plays a role

B. By describing famous novels about the cultural role of texting in American society

C. By listing the accomplishments of the two German men who created the medium of text messaging

D. By showing that text messaging was initially limited to 160 characters

4. The passage’s author most likely discusses the era before the War of Independence to:

F. demonstrate how historical figures refused to use text-messaging technology.

G. prompt the reader to do more research into the history of communication.

H. give a fun digression in an otherwise dry discussion of communication media.

J. show that forms of communication can provide historical records.

5. Which of the following people think or act in a way that is most similar to that of the naysayers described in the fifth paragraph (lines 43-60)?

A. Scientists who see improvements in medicine as an improvement in the quality of life

B. Sports journalists who say that a change in rules will destroy the integrity of a sport

C. Novelists who prefer to write on computers rather than with pen and paper

D. Historians who would prefer to read official documents rather than letters

6. According to the passage, of the following, who were the earliest contributors to the development of the medium of the text message?

F. Fields and Chacon

G. Scorsese and Franzen

H. Franzen and Wallace

J. Hillebrand and Ghillebaert

7. A character in a short story published in 1994 had this to say about text messages:

Say what you will about the “decline of real interaction”—I’ve had plenty of them that would’ve felt a lot more real if they’d happened in a sentence or two rather than a two-hour phone conversation.

Based on the passage, would Hillebrand agree or disagree with this statement?

A. Disagree, because 160 characters proved to be an inadequate number of characters.

B. Disagree, because he ultimately believed that most communication should occur by letter.

C. Agree, because he felt that the telephone was no longer an effective communicator.

D. Agree, because he thought that 160 characters was adequate to express most messages concisely.

8. Based on the passage, why might The Departed have been considered a film interested in contemporary issues?

F. It made a recent communication medium, text messaging, central to its story.

G. Its actors spoke in favor of text messaging, and the medium exploded in popularity after the film’s release.

H. It won an important award in honor of the quality of the filmmaking.

J. It showed that letter writing was no longer a sufficient way to communicate.

9. Based on the passage, when the author cites the saying “time is money” (line 23), she most likely means that a text message:

A. is an inexpensive way to send a message.

B. keeps a long-lasting record of people’s conversations.

C. is a quick way for people to communicate.

D. allows an intimacy that can otherwise take a long time to develop.

10. Based on the passage, Chacon suggests the number of people with whom people’s ancestors might have had interactions in order to:

F. state that the family unit is no longer as important as it once was.

G. suggest that new media can connect people in new ways.

H. imply that people in older times should have traveled more.

J. encourage readers to explore what their ancestors said in letters.

Summary

-

Use the 4-Step Basic Approach.

-

Step 1: Preview. Check the blurb, and map the questions. Star line and paragraph references and underline lead words.

-

Step 2: Work the Passage. Finish in 2–3 minutes. Look for and underline lead words. One option is to focus on only the first sentence of each paragraph.

-

Step 3: Work the Questions. Do Now questions that are easy to answer or whose answers are easy to find. Read what you need in a window of 5–10 lines to find your answer. Save for Later questions that are both hard to find and hard to answer.

-

Step 4: Work the Answers. Use POE to find your answer, particularly on Reasoning questions.

-

Skim and scan when you work the passage.

-

Read windows of text when you work the questions.

-

Look for topic sentences and transition words.