7

Smugglers and UFO Visions

Global Threats and the Warminster Thing, the Longleat UFO, Geomagnetic Reversals, and Afterlife Realms

In Cornwall, their illicit business over, Brother Joab and Mein Host walked to the car, got back in, lit their cigarettes, and burst out laughing in relief. Tension dropped away from their emotional bodies. It had all come together so fluidly. The first person they’d approached! It was hard to believe!

The gods must be with them, they decided.

And, because they’d been given a week to find a boat and a sailor to handle the mission, they had some time to spare. Now they could take their time getting back to London on small side roads and see where their intuitions would lead them.

It was as they were nearing the ancient city of Bath that my ward announced he suddenly remembered a person he knew from his life in London before the Process. He must be living somewhere around Bath, because his title was Viscount Weymouth, seventh marquess of Bath.

However, due to the idiosyncrasies of the English landowning classes, Longleat, the family seat of the marquesses of Bath, was not near Bath but instead close to the small Wiltshire village of Horningsham. A safari park, proudly announced to be the first one outside of Africa, had been opened a few years earlier in Longleat’s almost nine thousand acres of parkland and forest, so the place wasn’t hard to locate.

They’d spent the night in a bed-and-breakfast, so when they arrived at the gates of Longleat it was a bitter cold morning with ice still slick on the road and the boughs of the fine old trees drooping heavy with snow.

They drove slowly along the narrow driveway as it curled through the trees toward the great house, achieving just the effect the tireless Capability Brown must have hoped for when he had landscaped Longleat’s surrounding estate in the eighteenth century. Glimpses of the magnificent sixteenth-century structure appeared and disappeared through the barren trees. The sweeping lawns beyond became a white backdrop to the dark columns of the somnolent tree trunks closing in on either side of the long driveway.

Gradually the mansion came into full view, the very picture of an American’s idea of an English stately home. It was true. Longleat was certainly the most complete example of Elizabethan architecture in the country. The size and the siting of the house in a broad, shallow valley with the smooth, snow-white lawns sweeping away from the terraced entry contrasted harmoniously, if a little ominously, with the surrounding forest. The house predated by more than a hundred years the more famous Blenheim Palace in Oxfordshire, the even more monumental country house of the dukes of Marlborough.

Not only was Longleat far more appropriately scaled than the ridiculously massive Blenheim Palace, it had been spared Blenheim Palace’s discomforting confusion of styles. This hodgepodge was due to additions having been made to it over the centuries, which has rendered it an architectural travesty. (As a sidebar to my ward’s anecdote, I should add that Sir Christopher Wren had been commissioned to do some modifications to Longleat.)

As they drove cautiously along the seemingly endless driveway, my ward, drawing from his architectural history courses, told Joab the strange story behind the building of Blenheim Palace and Longleat.

It was the Duchess of Marlborough, he explained, who was determined to employ Sir Christopher Wren to design Blenheim Palace. As the finest architect in the country, Wren had just completed St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. He was being celebrated for that magnificent structure as well as the numerous fine churches he was designing and building after the Great Fire of 1666 had destroyed much of central London. However, the Duke of Marlborough, “presumably to spite his wife,” my ward said with a wink, decided not to use Sir Christopher Wren but rather settled on a man who wasn’t even an architect to design and build Blenheim Palace for him.

“It was really the old boy network in operation,” my ward was saying as he guided the Rover slowly around yet another tree-lined curve. “Vanbrugh was a local hero. He was locked up in the Bastille for espionage; spent over four years as a prisoner in Paris. He was known for having played his part in getting rid of the English king, James II, I think it was . . . a Catholic king, the last of ’em, thank God! England had gone Protestant by that time. Hard to believe these days, but that’s what preoccupied them. Religion. They didn’t know James secretly converted to Catholicism when he was in France, before he became king . . .”

“Wasn’t he the king who had his head cut off?” Brother Joab interrupted with the one interesting fact most Americans knew about this tumultuous period of English history.

“That’s his father, Charles I. Remember, we’d had ten years of Oliver Cromwell after King Charles was executed . . . Know what Cromwell called himself? The Puritan Moses! He was fanatical about getting Catholicism out of the country by the simple strategy of killing all the Catholics . . .”

“Like a kinda genocide, you mean?”

“Sure. It was one of the worst times . . . like a permanent civil war for fifty years. Actually, there were two actual civil wars, but it was Cromwell’s campaign in Ireland, murdering priests by the thousands . . . absolutely ruthless. You know two years after his death, they dug him up and posthumously executed him?”

“You have to be kiddin’ . . . after he was dead? God! They musta hated him!”

They were both pondering this absurdity when Brother Joab asked to stop the car for a moment. When he climbed back in, my ward was saying, “Believe me Joab, it gets weirder still. Next it was King Charles II. Sure he ruled as a Protestant, but guess what? He got converted to Catholicism on his deathbed.”

“I thought Henry VIII dealt with all of that,” Joab said. “That’s what we’re taught here.”

“Yeah, that was earlier. It just took a long time to work its way through—but James II was the last of the Catholic kings.”

“How do you know all this history stuff?” Joab asked as the bulk of Longleat started appearing, flickering through the trees.

“It’s an important point in English history,” my ward told him after a thoughtful pause. “Like one of those key turning points. It’s when we started liberating ourselves . . .”

But before he could continue, something else altogether was taking my ward’s attention—a vision so utterly unexpected that he tells me he retains the image in his mind to this day, as though it was burned on his eidetic screen.

I’m choosing to interrupt my narrative at this point because Mein Host’s particular fascination with this period of English history has been fueled by an element of which he was unaware until typing these words. Given that I’m adding these observations for my ward’s fuller understanding of that time, please feel free to skip the following historical digression.

They were indeed revolutionary times in England as the seventeenth century turned into the eighteenth; they were years of intense rebellion, of a growing restlessness with the old autocratic strictures like the Divine Right of Kings. Only forty years earlier a reigning king had been officially executed for the first (and last) time in English history. Much in the same way that America hasn’t yet truly recovered from the assassination of President Kennedy in 1963, the killing of Charles I, and the courage and charm with which he faced his death, had set the country reeling for years.

Oliver Cromwell’s assumption of power and his decade of implacably persecuting Roman Catholics wherever his agents could find them—recall what Mein Host told Brother Joab about Cromwell’s wanton murder of many thousands of Irish priests—all this created a climate of fear and insecurity that permeated the emotional tone of the British Isles. Many people in Protestant England may well have initially welcomed Cromwell’s anti-Catholic campaigns for the perks they got out of it. But what the people couldn’t have bargained for was the pervasive sense of collective shame that settled over the realm. Nobody in England had ever killed a king before. For most people, especially Catholics, this was second only to killing the pope, God’s representative in the world.

After the immediate exhilaration felt by Protestants at the execution of the Catholic King Charles in 1649 wore off, and the awful savagery of Cromwell’s troops had further divided the country, the national dishonor felt at the regicide contributed to a profound spiritual unrest.

It was, of course, one of those moments of opportunity in history when a small wave of rebel angels chose to incarnate into the mortal ascension process. In doing this at that point of time they helped lay the foundation for the scientific breakthroughs that characterize the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and came to fruition in the Industrial Revolution and the formation of the American experiment.

So with that in mind, consider the charmingly named Kit-Cat Club. The place flourished briefly in London, and its members have been credited with fomenting the Glorious Revolution of 1688—the uprising my ward mentioned previously when talking with Bother Joab. My ward’s research reveals that Horace Walpole, who was the son of Kit-Cat member Sir Robert Walpole, has written about the Kit-Cat Club. The author paints the club as eminently respectable or, in Walpole’s words, a place “generally mentioned as a set of wits.” But this was a heavily disguised summary of the Kit-Cat Club’s true intentions, which he later hints at when pointing out that the members were “in reality the patriots that saved Britain.”

Saved Britain, no less!

John Vanbrugh, later Sir John Vanbrugh, the man the Duke of Marlborough chose to design Blenheim Palace, was also a fellow member of this Kit-Cat Club. He was known for his radical views and his commitment to parliamentary democracy at this particularly crucial period in English politics. My ward had called Vanbrugh a local hero—and he really was!

John Vanbrugh was barely in his twenties when he spent more than four years as a political prisoner locked up in Paris for spying, before a prisoner exchange brought him back to London. He was one of the main players in the conspiracy that replaced the hated Catholic James II with the Protestant William of Orange from Holland. Before Vanbrugh was caught and imprisoned he’d been working under cover, liaising with William’s invasion fleet. The invaders anticipated a battle when they landed in England—King James’s army was far larger than William’s invasion force—but no, what little resistance there had crumbled, and the king went on the lam. It was the depth of winter, and within days he was caught by some fishermen and returned to London.

The House of Commons, sensibly enough for that age, decided against repeating the regicide that rid England of James’s father, Charles I, and so promptly imprisoned him. When James managed to escape to France only a week later—his second attempt in days—the English didn’t bother to pursue him. Executing his father had made a martyr of the king, and it wasn’t a mistake the English were going to make again—better to leave him be.

James had always felt more comfortable in Catholic France. Yet within only a couple of years after he’d been thrown out of England he was back again, compelled to try to reclaim his crown. However, after landing on the east coast of Ireland in 1690 with troops lent by the French king, James was humiliatingly defeated by William’s forces at the Battle of the Boyne.

This battle turned out to be a key point in the conflict between Catholics and Protestants that had been continuing since Henry VIII broke away from Rome more than a hundred and fifty years earlier. Now finally the Protestant-leaning English parliament was able to make laws to curtail the powers of the king. Thus it was under those novel restrictions that Prince William of Orange became King William III of England. As for James, he remained in France under the French king’s lavish protection, living in resentful exile, ever hoping he’d be invited to return in triumph as an English monarch until his death eleven years later effectively ended any chance for a Catholic king of England.

Plate 1. Sacred Equilibrium. As we balance the spiritual and material aspects of our natures, so also does Nature seek her own sacred equilibrium.

Plate 2. Invisible Allies. We’re of great interest to those who watch and care for us from behind the scrim of reality.

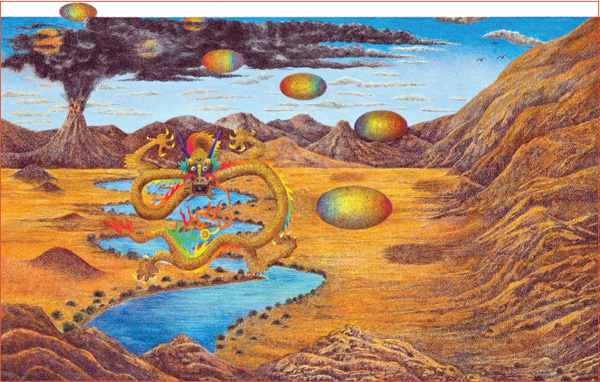

Plate 3. After the Earthquake. If or when Earth shrugs her shoulders will the North American continent split down the middle?

Plate 4. The Language of Light. Gestalt images of visual telepathy can dance their data on our eidetic screens.

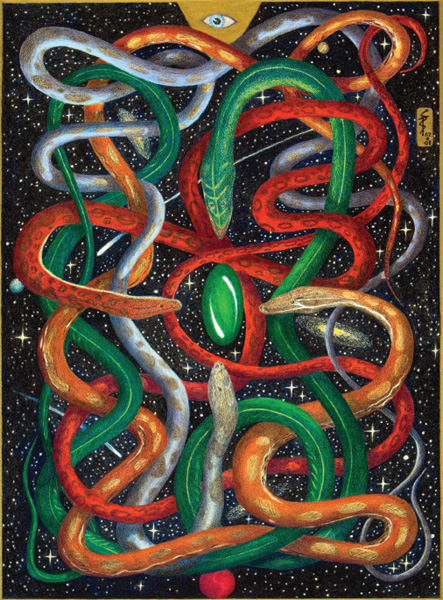

Plate 5. In the Beginning. There’s an ancient occult belief that before Earth was created four cosmic serpents gathered to bless the planet.

Plate 6. The Friendly Sun. Advice from a friendly extraterrestrial visiting from Itibi-Ra II: “First, make friends with your sun.”

Plate 7. Seeking Balance. I use my graphics as a form of biofeedback by which I can both observe the state of my inner equilibrium and correct it.

Plate 8. Passages of Earth. Mother Earth bends and shifts to accommodate the best humanity that brings her down through the ages.

This brief summary is, of course, a massive oversimplification of an event as significant to its age as the fall of the Berlin Wall was to the twentieth century. If the reader wishes to fill out their understanding of this vital moment in European history, the events are recent enough for considerably more detailed information to be readily accessible. Readers may also find it interesting to draw certain parallels between the events described here and those conflicts currently tearing apart the Middle East. Beneath the political and social upheavals, deeper than American or Russian interference in Middle East affairs, more fundamental than the lust far oil, the conflict is a religious one.

However, my purpose here in outlining some of the circumstances contributing to the glorious revolution of 1688 has been both to alert readers who may find an intuitive resonance with this period as well as to set a social context for the building of massive structures like Blenheim Palace and Longleat.

John Vanbrugh, after returning from his imprisonment in France, set his sights on the London theater, becoming a relatively successful playwright by the late 1690s. His plays were popular but soon became a bitter subject of controversy for their bawdiness and their lack of Protestant moral values. The spirit of the times had moved along once again, and this reflected directly in the changing public taste for theatrical events. Restoration comedies, which had been enthusiastically supported by King Charles II and were wildly popular during the previous thirty years with all classes of society for their saucy humor and sexual candor, had become unfashionable. The pendulum was swinging toward a new Protestant seriousness, leaving behind playwrights like Vanbrugh, with his rakes and fops and provoked wives. Vanbrugh then sensibly turned to his second love, architecture. Although he’d received no formal training other than what he’d picked up from gazing at the magnificent buildings in Paris from his time in France, he had friends in high places—namely, the Kit-Cat Club.

When the Duke of Marlborough decided on Vanbrugh to design Blenheim Palace, the playwright had already been working on the early stages of a stately home in North Yorkshire, in my ward’s words, “an absurdly monumental pile” known as Castle Howard. I’ve also heard him call the castle “a monstrous mishmash of styles, with its silly ornamental baroque turrets and its plaster cherubs.” A reader might recall the place as the fictional “Brideshead,” the stately home of the English television adaptation of Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited.

Although the primary architect of Castle Howard was the far more down-to-earth Nicholas Hawksmoor, a trained architect who’d worked previously for Sir Christopher Wren, it was John Vanbrugh who has been given credit for its weirdly idiosyncratic design. This became known as the European baroque style when other architects developed it further.

Yet if John Vanbrugh could boast of the success of his baroque innovations at Castle Howard, designing and building Blenheim Palace was going to be a horror from the very start. An architect’s nightmare! Everything was wrong. The money was never fully secured. The funds were voted on in parliament as a gift to the Duke of Marlborough for defeating the French king in 1704, yet in the excitement and generosity of victory there’d been no discussion of the actual cost. The money, however much it was going to cost, would be coming out of the royal purse—an arrangement that was, under any conditions, bound to end in conflict.

As the construction of Blenheim Palace dragged on, the queen became increasingly resentful of the constant demands for more money. The Duchess of Marlborough, in her turn, only made the situation worse. Feeling slighted by her husband’s choice of architect and taking out her fury on the unfortunate Vanbrugh, she formed a consuming hatred for “that upstart scribbler.” Their constant rows led to Vanbrugh being forbidden from ever again entering the site of the building he’d designed, as the financial brouhaha surrounding its creation would lead him to a public disgrace.

However, as though a curse hung over the palace, there was still a lot more disgrace to go around. Long before Blenheim Palace was completed the royal money dried up. Vast debts had been accumulated by the duke in his struggle to continue the building work, and, trading on his reputation, he made promises that were never kept. After a final, terrible row between the queen and the Duchess of Marlborough, both duke and duchess were exiled from the country. They owed a king’s ransom on the building and in the unpaid salaries of workers and could only finally return to England following the death of Queen Anne.

Although I’ve called this brief view of late-sixteenth-century English architecture one of my digressions, I’ve included it here not only to satisfy my ward’s longtime interest in architecture but also to hint at a period when a number of key players in important transitional periods in a nation’s history were incarnated rebel angels.

These selective infusions of rebel angels into mortal life on all thirty-seven rebel-held worlds have been occurring with greater frequency during those planets’ more recent histories. Such people, almost always completely unaware of their angelic heritages, can best be thought of as “agents of change,” having chosen prior to incarnation the roles they will hopefully fulfill over the course of their lives. They were frequently the heros and villains of history, but if there is a common feature it’s likely to be a preference for operating, as far as possible, behind the scenes. Unlike their purely mortal peers who seek public acclaim, incarnate rebel angels tend to withdraw from the fray when they’ve played their part.

It’s not my position to name names, unless there is something specific to be learned, but having some idea of the rebel angel personality as it enters mortal incarnation should allow interested readers to identify some of these people for themselves.

With that suggestion I will return to my narrative.

It’s a cold December day. Snow covers the ground.

A Rover Saloon threads its way cautiously through the skeletal trees lining the seemingly endless driveway of Longleat.

“From what I remember of my architectural history sessions,” my ward was saying as the house finally came into full view, “Longleat avoided all trouble. If Blenheim Palace was cursed, Longleat was . . .”

And he suddenly stopped speaking.

He was staring out over the vast expanse of the snow-covered lawns that stretched away down to their left.

“Did you see that?” There was an odd tone to my ward’s voice. No answer from Joab, who was looking at the house.

“Out of the corner of my eye . . . then when I looked it was gone! Joab, I swear it was there one moment and gone the next.”

“What? What’s gone? What the hell are you talking about?” This from the more phlegmatic Brother Joab.

“It was vast! An enormous spaceship. . . just sitting there on the snow. No, seriously! I saw it. It was transparent, like a jellyfish. Then, when I turned my head, it was gone. Disappeared.”

“C’mon, man! There’s nothing there! Look! Don’t spook me out!”

“You may be right, but I saw what I saw. If it was just an illusion or a hallucination it was a pretty weird one. The thing was enormous; it almost stretched all the way across the lawn . . . that must be, what? Three-quarters, half a mile?” My ward was still staring out across the snowy expanse of the lawn as the car scrunched on the gravel while pulling up to the house.

“That’s big, man! Half a mile!” Joab was humoring him as they got out of the car and climbed the stone steps to the fifteen-foot-high front door.

But I knew something remarkable had just occurred. After all, like all of my kind, I could clearly observe a sizable lenticular spacecraft parked in the fifth dimension on the front lawn of Longleat. What startled me, however, was that Mein Host had caught a glimpse of the ship. That spoke to me of his increasing sensitivity to the more subtle frequencies, as well as his growing confidence to trust what he perceived.

I believe, in retrospect, that choosing to trust his momentary vision of that Pleiadean craft while negotiating Brother Joab’s skepticism (well, he wasn’t looking in the right direction) was the first time I’d seen him practicing what he later called proceeding on an “as if true” basis. When there are no objective ways of establishing the truth or falsity of an event, a communication, or anything that occurs once, a wise person doesn’t reject such a thing out-of-hand because it doesn’t square with his or her preconceptions. No, the wise person proceeds on an as if true basis and keeps a sharp eye on what might happen next.

If something is true it resonates with an open heart. Even the most mundane truth is coherent with the greater Truth of the planet’s des-tiny. The truth persists, while falsity reveals itself false over time. This is the spiritual dynamic operating behind the well-worn phrase “the truth will out.”

Mein Host had only met Alexander Thynne, as the marquess preferred to be called, a couple of times under fairly informal circumstances, but they’d been able to talk about art and had enjoyed one another’s unorthodox opinions. The man was eight years older than my ward, and unlike most of his aristocratic peers he had a genuinely open and curious nature.

He welcomed both Processeans warmly, suspecting perhaps that because they were costumed as ostentatiously, though not as colorfully, as he was that they would share some of his more outrageous ideas. He was clearly a flamboyant dresser himself and an obsessive painter of erotic scenes, and was already becoming known for his free-love views. He was more of a hippy than a Peer of the Realm, although later in his life he would serve briefly in the House of Lords before “New Labor” shut out most of the hereditary peers.

It wasn’t a long conversation, because once they were sitting together there really wasn’t much to talk about. It wasn’t as if the marquess needed anything. He was one of the richest men in England, and while he agreed with a lot of what the Processeans saw as being ill with the world, he was far too wealthy and self-content to subscribe to the end-of-the-world theories held by the Process.

Before they left my ward gathered his courage and told their host about the enormous transparent spaceship he’d glimpsed in front of the house. He said how he couldn’t be certain. It had all happened so fast and it had been seen out of the corner of an eye. But that’s what it looked like. A vast, translucent spacecraft.

Expecting a casual dismissal or a burst of scornful laughter, Mein Host was pleasantly surprised at the response. No laughter. No scorn. Merely an enigmatic smile and a twinkle in the man’s blue eyes, and a sense that he knew more than he was prepared to say.

Did he appear to hurry them out after my ward’s question about the spaceship? Did he think at that point the pair were loonies? Had he seen the craft himself, perhaps? Did Joab too get the feeling he was holding something back? That he was hiding a secret? These were the questions the pair was pondering as they drove slowly back along the winding driveway.

It started to lightly snow again, and my ward was looking down under the dashboard and trying to fiddle with unfamiliar heater controls. Driving with his right hand and flipping switches and pushing knobs with his left, the radio splashed loudly on for a moment before he found the knob to silence it by finally hitting on the correct adjustment. When he looked back up through wipers barely scraping the wet snow off the windshield, his emotional body suddenly flushed crimson; Joab’s flaring moments later.

Another car had appeared on the road about twenty feet away. It loomed out of the snowy gloom and was now coming toward them on the narrow driveway.

It was a large black sedan, and it seemed to appear out of the snow from behind a thick stand of trees around which the road curled. It must have seemed impossible at first—they hadn’t seen another car on the estate. Yet, here one was, and now it was driving sedately toward them.

On a fine summer day the two cars would have been able to stop in time. Neither car was moving fast, perhaps ten or fifteen MPH at the most, but this was an icy road and the Rover P4 100’s clever arrangement of brakes—servo-assisted Giring disc brakes in front and drum brakes at the rear—were no match for the slick macadam. The car then started a long, slow, and not inelegant slide toward the oncoming car.

The big black sedan must have seen the Rover at about the same time, and the elderly driver, by stamping on his brakes, produced much the same effect, as his car also slid uncontrollably forward. I could see through his windshield the shocked expression on the driver’s face as the inevitable played itself out.

There was something strangely graceful about this little drama. If I had been more romantic I might have thought I was watching two monstrous metallic lovers being drawn ineluctably together, both sliding in magnificent grandeur toward one another, magnetized by some ancient memory to fall once again into each other’s arms.

Inside the Rover—the pride of Robert’s father’s eye and lent to them as an act of great trust—both men, their bodies rigid with tension, were bent forward, eyes glued to the windshield. Theirs was not such a romantic view as mine; no Greek gods were folding into a mutual embrace. Their mouths were wide open; their eyes staring into the snow. Joab’s right foot clamped down on a virtual brake, as my ward’s was on the real one, while they watched the distance between the two cars steadily, if slowly, diminishing. For them it might have appeared as if two planets, thrown from their orbits by some massive solar upheaval, were now floating majestically toward one another and their inexorable collision.

If I was a little scornful about the Rover’s brakes, I have nothing but admiration for the car’s balanced equilibrium as it covered the intervening space, skidding as it was over the icy surface in a perfectly straight line, as did the other car. Perhaps it was this that gave the drama its surreal, dreamlike quality. The two cars moved toward one another until coming to a sudden and jarring halt, bumper to bumper, hood to hood, headlights to headlights—and yet, by some miracle, no glass was broken, no fender bent. The headlight lenses on the two cars ended up within half an inch of one another.

Everyone in both cars sat very still for a long time before getting out and inspecting the fortuitous lack of damage. No police were required, so after a brief and friendly chat and an agreement that no one was at fault, hands were shaken and the drivers returned to the warmth of their vehicles. Backing up, the cars were easily separated from their tentative embrace, and both set off in their different directions.

“I know this is odd, Joab,” my ward said, as they drove slowly down the rest of the driveway. “But I had the strongest feeling something was trying to stop us from leaving Longleat, that there was more for us to learn there.”

“The spaceship, you mean? Oh man! Really?”

“You can laugh; you didn’t see it! But yeah, it could’ve been that. You saw how he looked when I asked him about the ship.”

“So why aren’t you turning back then?”

“It wasn’t that serious. What’d we say to the guy anyway? Perhaps if it’d been a bad crash, that’ve been a real stopper!”

They drove on in a thoughtful silence toward the town of Warminster. The snow had let up, but they drove with a new caution through the narrow country lanes. A watery sun flickered through the trees. Farther on the clouds cleared and the sun was shining, steam rising from the road as it dried out. Had Mein Host known the area better at that point in his life, he might have commented on the unusual number of microclimates in the southwestern region of the country. It might be raining in one valley and sunny in the adjacent one. In the next it would be stormy again, and moving past that to the lowlands the world would be swathed in mist.

The car was unaffected mechanically by the incident. Yet enough of its precious chrome-work was scratched to require the sincerest of apologies to Robert’s father with an offer—halfhearted though it would have to be, as they possessed no personal money—to cover the cost of the damage. Relieved to have his car back in one piece, the offer was generously ignored.

* * *

I left the dolphin pod when it became clear the ambient temperature had begun to rise, bringing with it the most violent and unpredictable weather I’d yet seen on this planet.

Hurricanes by the dozen swept across the Atlantic Ocean, ravaging the northern lands, the American seaboard, and sweeping over the Caribbean islands. Cyclones ripped through the Philippines, and other devastating storms wrenched trees from their roots across the Russian steppes. Lightning strikes ignited timber already dried and primed by the rising temperature of the atmosphere, spreading fires that raged across entire continents.

The sudden shift of the magnetic poles, a geomagnetic reversal achieved within a twenty-four-hour period that switched magnetic north and magnetic south, produced an additional hazard. The vast migrating herds of caribou broke into confusion, some running pellmell into lakes, or over cliffs, or into boggy marshland to be sucked under by the thousands. Many of these animals doubled back, only to become trapped and burned alive by raging forest fires. Flocks of birds, the crystals of magnetite in their brains feeding them inaccurate information, set off by the millions across an unfamiliar ocean, until, exhausted, they fell from the sky, blanketing the surface of the sea with an eiderdown of feathery bodies.

I think that of all I’d forced myself to observe over those terrible centuries, the sight of those millions of dead birds, too light to sink and yet weighty enough in their mass to calm the waves, was perhaps the most disconcerting sight of all. It was both utterly horrible in its tragic finality and yet quite one of the most disturbingly beautiful visions I’ve ever seen in a third-dimensional realm.

As I watched this unfamiliar and heartrending sight I found myself rising up higher in the astral without being consciously aware of doing it. I was now seeing still farther into an undulating plain of what looked like dirty white snow stretching in every direction. Then, moving still farther north, the unbroken blanket of death reached out far into the distance, until I could see the aurora borealis irradiating the darkness with its neon sheen, turning the feathered fields heaving beneath me into an incandescent echo of the silken skies.

I found the sight inconsolably beautiful.

That so much death is needed to contribute to a vision of such transcendent beauty has to be one of the idiosyncratic truths I’ve derived from my time on this world.

Need I go on with what I saw? The volcanic ash falling over human settlements, imprisoning the quotidian lives of the inhabitants into perpetual dioramas buried beneath many hundreds of feet of pumice.

Shall I tell of the terrible heat and floods that swept over the land, drowning all in the water’s path, washing away land bridges, separating islands forever from the mainland?

Or of the clouds of brightly colored butterflies, their migration routes disrupted by geomagnetic anomalies, flying in their masses into the sulfuric smoke pouring from volcanic vents?

Or perhaps of the enormous herd of impala I saw on the African plains, wildly leaping and running panic-struck from a fire driven by gale-force winds? Well, possibly just this one example, if only to illustrate that under such convulsive global conditions, heartrending and yet exhilaratingly intense visions become all too common.

It was inevitable, of course, that the immense herd of impala would eventually tire and falter. The fire line, a wall of burning grassland stretching far into the smoke, was moving rapidly, although not quite as fast as the herd. However, unlike the impalas, the fire was relentless in its progress. To the poor creatures it must have felt as if their worst nightmare was pursuing them, the flames first selecting the slow ones, the calves and mothers, the pregnant, the old and frail, and cruelly picking them off.

Still the fire rushed on.

The creatures’ graceful leaps became shorter and more laborious. The flames, nipping at their heels, would spur them on in bursts, these sudden spurts of speed only making their progress that much more chaotic. Those at the rear of the herd were leaping in panic over, and onto, the backs of the slower ones in front of them. Hooves thrashed out as they collided, sometimes in midair, falling in heaps of broken limbs, some struggling back up to drag themselves on, stumbling over their dead and dying, only to burst into flames, ignited by the roaring onrush of the fire.

Gradually the herd of tens of thousands of these elegant, beautiful creatures moved slower and slower, although it seemed to me as though the fire itself was accelerating. The animals’ progress—in fits and starts, somehow communicating almost instantaneously throughout the herd—became more labored as increasing numbers of impala were flaring up in flames.

But that wasn’t the worst of it.

The impalas were exploding! The wretched creatures were erupting in sudden bursts of bright crimson and torched flesh.

Not unlike the pretty explosions of antiaircraft shells high overhead that my ward had watched as a child from his garden, impalas were exploding as far as I could see. Like an obscenely conceived fireworks display, each detonation was accompanied by an eruption of flaming body parts, which then fell on the bodies of those running close behind, causing them, in turn, to flare up and explode.

The heat was so intense as it swept onward that it was igniting the gasses in the creatures’ stomachs. Frequently the impalas exploded at the peak of one of their hysterical leaps. As the fire finally gained on them, overtaking the creatures and consuming them, it appeared for all the world like the gods were making popcorn on a fiery pan the size of a small African country. Or perhaps, with all that leaping and exploding, and because the front of the fire was moving in a straight line through the herd, I imagined that I might have been looking down at a gigantic basse-lisse loom. The weft of the flaming cloth rose and fell as though an invisible shuttle was flying back and forth, moving inexorably forward and delineated by a line of those vividly colored explosions.

I don’t mean to make light of this horrifying scene, but it does reflect the degree to which I was growing inured and hardened by what I’d been observing over those tumultuous centuries. Sometimes I find it’s only by focusing on the ominous beauty of destruction, or by using the lens of gallows humor, that I can deal with the pain and shame of having to observe such horrors.

Yet it was precisely in order to witness such horrors that I forced myself to stay and continue to observe these catastrophes. This time I’d determined I would not retreat to another world simply to avoid unpleasant reminders playing out before me of the decisions we angels made during and after Lucifer’s rebellion. So I really have no basis for complaints.

However, there is something else that needs to be said. It relates as much to the massive die-off of human and animal life I witnessed in those times as it does to the massacre of millions in a war, or to the passing of a single human being. It concerns the nature of physical death and how death is perceived by the angels within the larger context of a mortal’s eternal life.

The Multiverse in general, and the angels who serve the mortal ascension process, have a very different understanding of human mortality than do regular human beings. As members of a species unavoidably aware of our immortality, we angels have no real comprehension of mortal death or the terrors it carries for so many people.

For most humans physical death remains the great mystery of life, and, given that, almost anything can be fabricated about the afterlife by the unscrupulous. Religions in general, to state what has hopefully become obvious, have been among the worst of these offenders, with their stories of heavens and hells used as manipulative devices to control their flocks. Classic Christian fundamentalists, for example, may well “believe” they will go to heaven as a reward for their beliefs, but it will be the fear of going to hell that will dominate and shape their lives.

Atheists, or nonbelievers, by sensibly rejecting all the religious speculation about the afterlife, don’t necessarily find themselves in a much stronger position. Their dismissal of a religion’s guesswork about the afterlife may satisfy their mental intelligence, but with nothing of substance to replace it, their fear of death comes to dominate their emotional intelligence, which then has to be repressed and denied.

It is the next stage of this downward spiral that is most dangerous. In dismissing any spiritual reality the atheist derives no authentic wisdom to feed his spiritual body. His natural animal fear of death will tend to overwhelm his emotional body, and because it’s unsustainable for any being to live with a constant fear of death, his mental intelligence will be used to justify repressing the fear in his emotional body.

The results of repression will manifest in a variety of ways. At its worst it will show in the tyrant as a callous indifference to other people’s deaths or in an authoritarian parent’s brutal overreaction to a child’s minor indiscretion. In a less obvious form the repressed fear surfaces as the preoccupation with death and violence seen every day of the week in the films and television shows of contemporary popular culture—an obsession with violence shared by both the producers and the consumers.

In some intellectuals this fear of death can result in a refusal to even consider the afterlife as real; in others it might manifest as a knee-jerk denial of any validity in the near-death experience. In still others their impending death is an elaborate drama in which their atheism becomes the badge of courage in so bravely facing their permanent extinction. If it was true that the death of the material body was the end of their existence, their stoicism would indeed be admirable. As it is, such people are merely victims of their own misconceptions—convicts imprisoned by their own convictions.

In many doctors and in the medical profession in general, their repressed fear of death will reveal itself in their need to compulsively revive the dying at all costs, regardless of their patient’s desire and the Natural Order of life. All this so-called reverence for life, and I’m not denying the many acts of heroism this produces, is in reality another cloak to this pathology. As a result old people can linger on, their bodies victim of a medical system that profits from keeping them alive, and as likely as not, they’ll be denied the reassurance of an afterlife.

There is an aspect of this pathology I can understand. In terms of whether there’s an afterlife, it’s the very human fear of being fooled or deluded yet again. Life in general has become so distorted over the thousands of years of planetary isolation that, as my ward likes to say, “everything has become upside down.” People sense this on a deep level and the gap between the world in which they live, and the reality they know in their hearts they intuitively know to be true.

A tragic example of this, if it wasn’t so amusing, are those scientists who dedicate themselves to proving that NDEs can be stimulated electrically in the waking brain. Sure, they can produce weird feelings in the subject, some flashes of light and what is assumed to be the tunnel that features in some NDEs. This evidence is then presented as a refutation of what anyone who has had an authentic NDE knows will likely be the most profound spiritual experience of their lives.

It’s a subject of some wonderment for angels to see the extraordinary lengths some mortals will go to hide their eyes from the reality of death. While it is sadly misguided, it’s a misconception that carries with it the hidden promise of a wonderful surprise at the end of such people’s lives.

Yes, life continues after physical death, and it’s well worth factoring that in to the way you live your life. Not out of fear for a fictional hell, nor from a desire for an eternity of pleasure in an equally fictitious heaven, but from the knowledge that this human lifetime is but the first stage of a spiritual career that will take you deep into the Multiverse, and, ultimately, far beyond and into the presence of the Creator of All.