Chapter 3

1 Thessalonians 2:17–3:13

Literary Context

At the heart of this section is the occasion that prompted Paul to write the letter: the return of Timothy with good news about the Thessalonian church (3:6). The apostle also gives details about why Timothy went to them in the first place.

Many ancient letters contained an “itinerary,” that is, a description of the author’s travel plans. Romans 15:22–29 is an example of a Pauline itinerary. Nevertheless, in 1 Thessalonians, he does not write about his future travel; rather, he describes what he wished he could have done but did not.

Some have thought that this section and perhaps 2:1–13 is apologetic, that is, to excuse Paul and Silas for having sent Timothy instead of going to Thessalonica themselves. There may be some truth in that, although the exegete should remember Timothy had earlier explained in detail why Paul and Silas had not been able to return; why would Paul need to offer another excuse? It is better to see 2:17–3:13 fundamentally as an affirmation of their love and concern for the Thessalonians. Paul also underscores what they value in that church: their love (3:12; see 1:3 and 4:9–10) and the prospect of being holy at the end of the age (3:13; see 5:23). Paul ends with a prayer that God and Jesus Christ will bless the believers in Thessalonica and that Paul and Silas will be able to see them soon (3:11–13). This eschatological reference ties the section into the other references to the parousia in the letter and the pressing need to be found holy at Christ’s coming.

- IV. Recapitulation: Why They Regularly Give Thanks for the Thessalonians (2:13–16) [inclusio with 1:2]

- V. Paul and Silas’ Frustrated Travel Plans and a Solution (2:17–3:13)

- A. Paul and Silas had a deep desire to revisit the Thessalonians, but Satan hindered them (2:17–20)

- B. Timothy carried out a reconnaissance of the Thessalonian church (3:1–5)

- C. Timothy returned (3:6a)

- D. Timothy conveyed joyful information about the state of the church (3:6b–10)

- E. The new information makes Paul and Silas pray all the more (3:11–13)

- VI. Paraenesis: The Gospel Ethic in a Gentile environment (4:1–12)

Main Idea

Paul assures the Thessalonians that he and Silas had yearned for a return visit to their city, but they had been blocked by Satan. Timothy’s trip to Thessalonica accomplished what the apostles would have liked to have done. The news upon his return gives Paul and Silas much relief and leads them to pray even more for these disciples in tribulation.

Translation

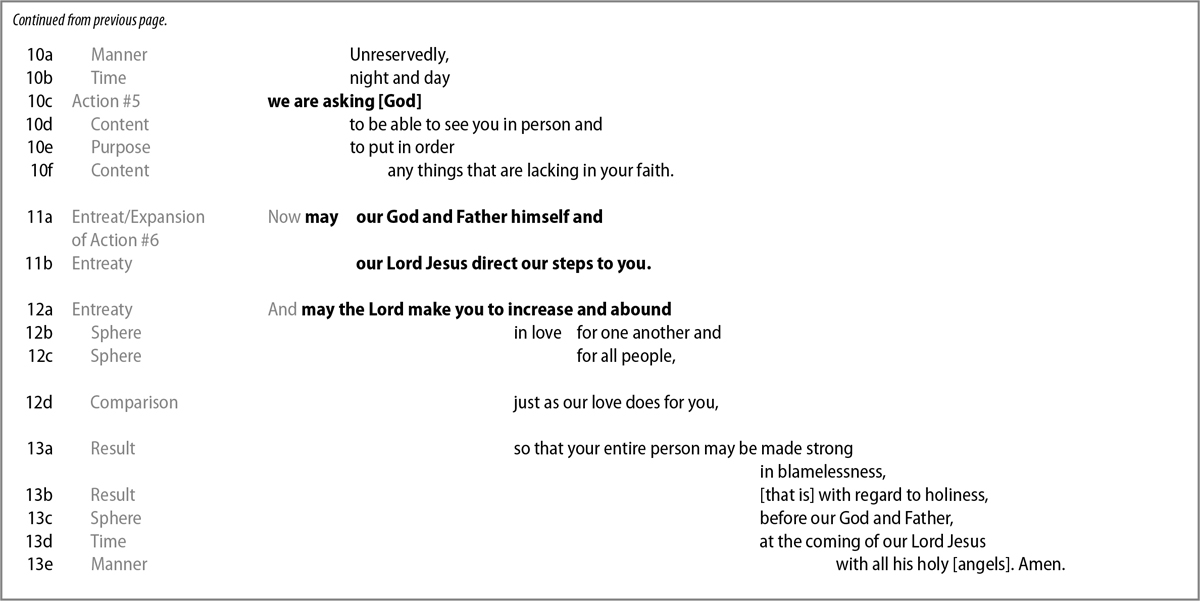

Structure

The section describes what has taken place between the departure of the team from Macedonia to the return of Timothy. Paul turns away from the oppression given by unbelieving Jews in 2:16 to another set of troubles, marking the transition with “meanwhile we” (ἡμεῖς δέ, a better translation of the conjunction δέ than merely “and”). He delineates five actions/events in 2:17–3:10 that are predicated on the forced separation of Paul and Silas from the Thessalonians, and the happenstance that young Timothy was able to go to and from the church unchecked.

First: “we made every possible effort to see you” (2:17e); the parallel “we resolved to go to you” (2:18) is marked by “and so” (διότι). The language is highly emotive here: orphaned, face-to-face, heart, abundantly, every possible effort, great desire, all alone, and so forth. Paul develops that resolution in 2:19–20, saying that their desire was because (marked by γάρ twice) the Thessalonians were so valuable to them.

Second: following hard on the first statement is that “Satan blocked” Paul and Silas (2:18c). Paul introduces this event with a bare “and” (καί), which seems to be a deliberate understatement on his part. It is an abrupt, harsh description, without elaboration: Satan just shut us down.

Third: the apostles came up with a “Plan B” (3:1–5), marked with “and so” (διό in 3:1a, διὰ τοῦτο in 3:5a) and a further note about how unbearable it was to be separated from their friends. Thus, they sent Timothy alone to Thessalonica (3:2). He was charged with (εἰς τό denoting purpose) “strengthening” (3:2d) and “encouraging” them (3:2e). The apostles were concerned “lest” (μηδένα + infinitive in 3:3a; similarly, “whether,” μή πως in 3:5c) they had been shaken (3:3a). Of course, Paul states, using reminder language and “for” (γάρ), they already well knew that they would be experiencing this sort of persecution (3:3b–4).

Fourth: Timothy returns to Paul and Silas in, we infer, Corinth and gives them a good report about the church (3:6–8). It is syntactically striking that his return is expressed in a genitive absolute, possibly for dramatic effect: “Timothy has come … and has announced the good news” (ἐλθόντος Τιμοθέου … εὐαγγελισαμένου). Timothy’s report is described as a brief list (3:6c-g).

Fifth: Paul and Silas react to the good news to the Thessalonians (3:7–10) and offer up prayer (3:11–13). They are encouraged “in that way” or “for that reason” (διὰ τοῦτου, 3:7a), followed up by “because of” (διά, 3:7c), “because” (ὅτι, 3:8a) and “for” (γάρ, left untranslated in 9a). Paul once again reverts to highly emotional language as he reports how they pray and give thanks to God for the Thessalonians. Suddenly, the reader is reminded that this was exactly how the letter began, with their unceasing prayer in 1:2–3. That text and 3:9–10 form an inclusio—two similar passages that stand at the beginning and end of a section of text. Now that we learn of the results of Timothy’s journey and report, we understand why the apostles were so exuberant in the opening verses. Paul began the first chapter writing about the effect; only now do we learn about the cause.

In 3:11–13 Paul not only reports how they pray; he goes ahead and prays for them, then and there as he dictates the letter. He introduces the benediction with “and” (δέ), but it is better translated as “now,” to match the flow of thought in the original and also to remind English readers of benedictions that they have heard in church, as in, “And now may the Lord, etc.” (see also 5:23). It is theologically significant that the apostles pray to both “our God and Father” and “our Lord Jesus,” a pattern that one finds throughout these early Pauline letters. There are two main petitions. First, he prays that the Father and the Lord Jesus “direct our steps to you.” This is meant to be taken literally, asking that the apostles will be able to return to Thessalonica. The second petition is much longer and has to do with the spiritual growth of the disciples, that they will abound in love, resulting in complete holiness.

Exegetical Outline

- I. Paul’s and Silas’s Deep Desire to Revisit the Thessalonians, but Satan’s Hindrance (2:17–20)

- II. Timothy and the Thessalonian Church (3:1–10)

- A. Timothy’s reconnaissance with the Thessalonian church (3:1–5)

- B. Timothy’s return (3:6a)

- C. Timothy’s joyfully conveying information about the Thessalonian church (3:6b–10)

- III. The New Information Makes Paul and Silas Pray All the More (3:11–13)

- A. To be able to visit them (3:11)

- B. That the Thessalonians’ love may continue to grow (3:12)

- C. That they may be ready for Christ’s coming (3:13)

Explanation of the Text

2:17a-c Meanwhile we, brothers and sisters, because we were made orphans from you for a time (Ἡμεῖς δέ, ἀδελφοί, ἀπορφανισθέντες ἀφ’ ὑμῶν πρὸς καιρὸν ὥρας). Now Paul returns to the first person plural with “meanwhile we” (ἡμεῖς δέ). “Brothers and sisters” draws the readers’ attention as Paul turns to a new theme: where they had been since last seen in Thessalonica. It is difficult to harmonize precisely this section of the letter with Acts 17 (see the Introduction, “The Second Missionary Journey,” for details).

In order to impress on the disciples their commitment to Thessalonica, Paul describes the psychological state of the team during the period of separation. In 2:1–12, he and Silas were like children, mothers, and fathers. Now they are like “orphans,” lost and worried. The verb “to be made an orphan” (ἀπορφανίζω) was at times used in a generic sense of “being deprived of”;1 nevertheless, the more specific sense of “to be made an orphan” makes good sense in a letter where family relationships are so key. Perhaps readers would have expected Paul to say “you were orphaned from us,” since Paul and team were “fathers/mothers” to the Thessalonians.2 But the natural sense of the verb shows that he is building on 2:7: now the little children have walked off and lost their parents.3

The phrase “for a time” (πρὸς καιρὸν ὥρας) usually indicates a relatively short period, not to be thought of as more than a period of weeks. Paul is probably not indicating the whole elapsed time since his departure from Thessalonica, but rather between their departure and the decision to send Timothy. Paul will later write something similar to the Romans, but instead will say that he had been hindered for a long time (τὰ πολλά, Rom 15:22; see 1:10, 13). That time period probably spanned eight or so years, commencing at the point he first started on the Via Egnatia but was then diverted to Berea (Acts 17:10).

2:17d [Orphaned from you] in person, not in our hearts (προσώπῳ οὐ καρδίᾳ). The apostolic team is physically but not emotionally separated from their Thessalonian friends. They are apart, literally, “with respect to the face” (προσώπῳ), “face” having reference to presence “in person.” Paul later speaks of believers who have never met him personally (Col 2:1). But despite their geographical separation from Thessalonica, the team was not orphaned with respect to the “heart.” In this case—unlike 2:4—“heart” (καρδία) does refer to the seat of the emotions.4 The “orphans” feel a strong bond with the church that distance cannot dilute. Here as always in his letters, Paul is no dispassionate functionary.

2:17e-f Made every possible effort to see you in person, with great desire (περισσοτέρως ἐσπουδάσαμεν τὸ πρόσωπον ὑμῶν ἰδεῖν ἐν πολλῇ ἐπιθυμίᾳ). This strong statement is fortified with Paul’s use of an adverb, a strong verb, and a prepositional phrase. “Every possible” (περισσοτέρως) means “even much more.” Paul uses it elsewhere to speak of Titus’s deep commitment to the Corinthians (see 2 Cor 7:15). They also “make every effort” (σπουδάζω); he uses this verb elsewhere in the context of “do your best to come to me quickly” (2 Tim 4:9; 4:21; Titus 3:12). Paul augments this further by saying “with great desire” (ἐν πολλῇ ἐπιθυμίᾳ). The language is unequivocal: it was not for lack of serious, heartfelt effort that Paul and Silas did not return to Thessalonica.

2:18a And so we resolved to go to you (διότι ἠθελήσαμεν ἐλθεῖν πρὸς ὑμᾶς). Added as it is to the phrases at the end of 2:17, this verse lends an air of drama to their dilemma. “And so” or “that is why” (διότι) we resolved this action. “Resolved” (ἠθελήσαμεν) is a better rendering than merely “to wish,” seeing that the clause is meant to draw a conclusion from their feelings in 2:17.

2:18b To be sure, I, Paul, more than once (ἐγὼ μὲν Παῦλος καὶ ἅπαξ καὶ δίς). And still Paul pushes on, telling of his own multiple attempts to revisit them. Because this is such a personal heart desire of his, he lapses from first person plural to the singular “I, Paul” (ἐγὼ … Παῦλος). Paul as an individual breaks in and interrupts the more consistent “we”—the senders of the letter.

The language now alternates back and forth from “I” to “we”:

- 2:17 we were made orphans from you

- 2:17 we made every possible effort

- 2:18 we resolved to go to you, to be sure, I, Paul, more than once–

- 2:18 and Satan blocked us

- 3:1 when we could stand it no longer, we determined to be left alone in Athens

- 3:2 we sent Timothy, our brother

- 3:4 when we were

- 3:4 we told you

- 3:5 when I could stand it no longer

- 3:5 I sent to find out about your faith

- 3:5 our labor

- 3:6 Timothy has come to us from you [and back consistently to the plural “we”]

One possible interpretation is that Paul has been using “we” as an “epistolary” or editorial plural; that is, that Paul is writing as the sole author, and “we” is a device, not a literal reference to himself and Silas (but not Timothy—he is referred to in the third person). Yet Samuel Byskorg offers a thorough analysis of the first person plural in the epistolary genre and demonstrates that a literary plural is unlikely. In Greco-Roman letters it was extraordinarily rare, with perhaps nine known examples. It is more common but still unusual in Jewish letters: “The samples of [Jewish] letters with several senders referred to above exhibit no instance of the literary plural…. The ‘we’ of these letters mostly includes all the senders.” He offers the rule, that “if other criteria of analysis allow an interpretation of either a real or a literary plural, the former is to be preferred.”5

There are other telling arguments in favor of “we” being literally the plural, “we, Silas and I.” (1) There is no clear evidence that Paul elsewhere uses an epistolary plural: “we” and “I” have their normal reference to plural or singular.6 (2) Paul writes with Silas and Timothy in 1–2 Thessalonians to a degree that he does not, for example, represent Sosthenes in 1 Corinthians. (3) There are “we” statements that would hardly function as having a singular reference, such as 2:6 (where “we” = “apostles,” plural, not Paul as “an” apostle) and 2:18 (where the plural “we resolved” alternates with “I, Paul”—otherwise, Paul would be repeating himself and probably mystifying his audience by the switch). (4) First Thessalonians 2:17–3:6 would be confusing if Paul were going back and forth between Paul-as-we and Paul-as-I.

Thus, “we” in this section means Paul and Silas (see comments on 1:1). As elsewhere in the Thessalonian letters, Paul makes reference to the prayers, ministry, and travel plans of three men who have deep ties with the church and whose representation in the letters would have come as a great comfort to them during their trials.

“To be sure” (μέν) captures Paul’s emphatic tone. “More than once” (ἅπαξ καὶ δίς, lit., “once and twice”) is an idiomatic phrase that does not literally mean “twice” but “more than once, and perhaps multiple times” (see also Phil 4:16, where Paul refers to the multiple gifts that the Philippians had sent Paul).

2:18c And Satan blocked us (καὶ ἐνέκοψεν ἡμᾶς ὁ Σατανᾶς). With “and” (καί) Paul reveals why their plan did not succeed: something “blocked” or “hindered” them. Because the Greek language is highly inflected (i.e., syntax is demonstrated by word endings), sentence structure is more elastic than it is in English. As in this verse, it was possible to delay the subject until the end of a clause. Here Paul delays the subject of the verb for the sake of emphasis, making it something like: “and he blocked us … Satan!”

“Satan” (ὁ Σατανᾶς, an alternate spelling is Σατάν) is a loanword; that is, it was transliterated from the Hebrew śāṭān. The word was at times used to mean any sort of adversary (cf. 1 Kgs 11:14; also Sir 21:27—“When an ungodly person curses an adversary, he curses himself”). It could also be used to refer to the chief angelic adversary of God’s people (see Job 1:6). It was translated into Greek as “devil/adversary” (διάβολος). In intertestamental Jewish literature, Satan played a larger role than he did in the Old Testament; at Qumran Belial or the angel of darkness is the being who stands behind the evil inclination and prompts people to sin.7

In the Gospels and Revelation, “Satan” is a common name for the principal adversary of God. It is used ten times in Paul’s letters and in a Pauline speech in Acts 26:18. A messenger of Satan causes Paul’s thorn in the flesh (2 Cor 12:7). Satan is the cause of false teaching (2 Cor 11:14; 1 Tim 5:15) and temptation (1 Cor 7:5). He is the one who stands behind the Man of Sin (2 Thess 2:9). Paul uses “devil” (διάβολος) eight times in his letters, more or less interchangeably with “Satan”; he uses the term “child of the devil” for Elymas in Acts 13:10.

From the very beginning Satan hoped to pull human beings away from God (Gen 3:5), and his longing is that they follow idols. Now, under the power of the gospel, some are turning back from idols (1 Thess 1:10). No wonder, then, that Satan wished to block the evangelists, who have turned a small but growing number of Gentiles away from false gods to follow the true and living Creator.8 The reader might be saddened at this point, thinking back a few sentences and drawing the inevitable conclusion that the Judeans who oppose the Gentile mission (2:15–16) are actively participating in a satanic work.

In this verse and in 2 Thess 2:9, Paul demonstrates no interest in the more arcane mysteries of the apocalypses of the Second Temple period. Nevertheless, he dwells within the conceptual framework of Daniel and Revelation. His universe has ample space for battles between spiritual powers. We find more details by comparing 1 Thess 2:18 with Acts 16:6–10:

Paul and his companions traveled throughout the region of Phrygia and Galatia, having been kept [κωλυθέντες] by the Holy Spirit from preaching the word in the province of Asia. When they came to the border of Mysia, they tried to enter Bithynia, but the Spirit of Jesus would not allow [οὐκ εἴασεν] them to. So they passed by Mysia and went down to Troas. During the night Paul had a vision of a man of Macedonia standing and begging him, “Come over to Macedonia and help us.” After Paul had seen the vision, we got ready at once to leave for Macedonia, concluding that God had called us to preach the gospel to them.

This extraordinary chain of events led Paul and his team to cross over to Macedonia, and within a short time, to plant the faith in Thessalonica. Apart from the “night vision,” Acts does not give details of how the Spirit communicated his wishes to the team. Some have suggested that they were not allowed by local governments to cross over into Asia (as Paul would later find himself able to do on his third missionary journey) and Bithynia. While this is a possible interpretation, the pattern of Acts suggests an explanation that comes from the supernatural realm. In Acts 13:2, “the Holy Spirit said” refers to a word given by one of the prophets who was present, during a period of worship and fasting. This resulted in Saul, Barnabas, and Mark’s campaign in Cyprus. After the Jerusalem Council, Silas and Judas Barsabbas went to Antioch as witnesses of the Council’s decision: they were both known as prophets (Acts 15:32).

Later in Acts, God sent a word of prophecy to warn Paul about the trouble he would face in Jerusalem (Acts 20:22–23; 21:10–14; see the standard commentaries for the difficulties surrounding prophecy in that section). Given the general trend within Acts, the most natural interpretation of 16:6–7 is that someone, perhaps Silas, uttered a prophecy that warded them off from Asia and Bithynia, but did not go on to give positive direction as to where to go. Then in Acts 16:9–10 Paul had a vision that they interpreted as guiding them to cross over to Macedonia. The Spirit thus gave them three signals concerning where they were to go.

So, God at times gives the apostle a direct word about where to go or not go. Yet now, Paul states that it is Satan, not the Spirit, who has hindered him and Silas (but apparently not Timothy) from going to Thessalonica. But how did they apprehend that this hindering was from Satan and not from the Spirit (as in Acts 16:7)? Bruce believes it was possible to discern the impediment’s source from its result: “It was probably evident—in retrospect, if not immediately—that the one check worked out for the advance of the gospel and the other for its hindrance.”9

While plausible, this is impossible to prove. After all, Acts 16:6–7 implies that the gospel was “hindered” from going into Asia and Bithynia; that is, the advance of the gospel was checked by Jesus. What did Satan’s block look like, to make it distinguishable from what Jesus did? Again, the facts of the case are elusive. In the case of the blocked path from Athens to Thessalonica, it is possible that Satan was hindering them by means of the onerous bail that Jason had posted, a legal prohibition that obstructed the two senior members but not Timothy. Paul might have employed a hermeneutic that interpreted any problem caused by the government to be satanic. Many other speculations are possible, ranging from bad weather to illness to spiritual warfare. Nevertheless, by some method—perhaps more supernatural knowledge given through Silas?—Paul knows it is Satan who has blocked their path, not just random circumstance and not the Holy Spirit.

The reader must press still further and understand Paul in the broader context of the Scripture. Paul would have believed that, while Satan could do harm to the saints, he could never do so apart from God’s permission. This is demonstrated clearly by Job 1:12; 2:6. The doctrine is even clearer in Dan 10:10–15, where Daniel prayed fervently for enlightenment, the angel who came in answer was blocked, and Michael came to relieve him and send him on his way to Daniel. Behind these accounts is the faith that Satan cannot act apart from divine leave.

It is probable that on his first reconnaissance Timothy had communicated to the church the specific details of why Paul and Silas had not returned; this reference to Satan was therefore comprehended in light of the information that they already possessed. Immediately helpful for the Thessalonians was the knowledge that it took the archenemy of God, Satan himself, to keep Paul and Silas from personally visiting them.

Paul communicates several important theological points in one statement. First, Satan is a foe whose presence is immediately palpable, not simply an abstract principle of evil. Second, he is able to impede such key apostles as Paul and Silas. Third, Satan’s hindrance continues, despite the many prayers to God for relief. Fourth, Paul and his team continue to pray for the satanic barrier to be eliminated, even though it has not been lifted thus far—their battle with Satan required vigilance. Fifth, Paul is not reticent about admitting that he, an apostle, has been successfully held up by Satan. Something similar appears in 2 Cor 12:7, where the “thorn in my flesh” is “an messenger of Satan, to torment me.” His spiritual modesty is a rebuke to those leaders who through the centuries have dared to imply that Satan is their trained poodle.10

2:19a-d [We wanted to see you], because who gives us hope or joy, or who is a prize to boast of—if not you all (τίς γὰρ ἡμῶν ἐλπὶς ἢ χαρὰ ἢ στέφανος καυχήσεως—ἢ οὐχὶ καὶ ὑμεῖς). Here is why they want to visit the Thessalonians; it is an affectionate cry from the heart.

“Crown” (στέφανος) might refer to the headwear of a king; this is how it is consistently used in Revelation. It may also refer to a prize won for athletic or civic achievement, a chaplet woven of some flowers or branches and is a symbolic honor given to a victor.11 It is used metaphorically by Paul to speak of the success he hopes to gain (here and in 1 Cor 9:24–25).

In Paul’s usage, “boasting” (καύχησις) is double-edged. It may refer to prideful attitudes by sinful people (Rom 3:27). But positively, it may refer to legitimate glorying in God (Rom 15:17) or in what a person can do in God’s power (1 Cor 15:31): “Let the one who boasts boast in the Lord” (1 Cor 1:31, which uses the cognate verb; also 2 Cor 10:17). This positive use is Paul’s intent here. The prize here is not some crown that he anticipates receiving: rather, the Thessalonians themselves are those concerning whom Paul will glory at the coming of Christ. Philippians 4:1 is similar, where Paul speaks of the Philippians’ steadfastness in the faith: “Therefore, my brothers and sisters, you whom I love and long for, my joy and crown, stand firm in the Lord in this way, dear friends!”

“If not you all” (ἢ οὐχὶ καὶ ὑμεῖς) is awkward; Paul probably adds the particle (ἤ, lit., “or”) to make it parallel with the preceding phrases.

2:19e In the presence of our Lord Jesus at his coming? (ἔμπροσθεν τοῦ κυρίου ἡμῶν Ἰησοῦ ἐν τῇ αὐτοῦ παρουσίᾳ;). Paul returns to the eschatological, “at” (ἐν) Jesus’ second coming.12 The parousia is not simply a deliverance from God’s wrath (1:10), but positively a time of glory and rejoicing. “In the presence of” (ἔμπροσθεν) is used of appearing before God or Christ, for example, at the judgment (Matt 25:32; 2 Cor 5:10). In other contexts the preposition may refer to prayer or more generally to existence in God’s presence (1 Thess 1:3; 3:9). “Coming” (παρουσία) is a semitechnical expression in the New Testament. The return of Jesus came to be called his parousia13 or epiphany (ἐπιφάνεια, e.g., 2 Thess 2:8) or revelation (ἀποκάλυψις, 1 Cor 1:7; 2 Thess 1:7). At Jesus’ coming the Thessalonian converts will redound to the team’s credit.

2:20 Yes, it is you all who bring us pride and joy (ὑμεῖς γάρ ἐστε ἡ δόξα ἡμῶν καὶ ἡ χαρά). Again, Paul affirms how they deeply value the disciples. We render “for” (γάρ) as “yes” in order to give it its proper emphatic meaning. Paul answers his own rhetorical question in 2:19 by echoing—although not word for word—his reference to “hope and joy or who is a prize to boast of.” Here he uses “glory” (ἡ δόξα) rather than the synonymous “prize to boast of.” We translate it with the present tense, although from the context, Paul is thinking ahead to the second coming.

3:1 And so, when we could stand it no longer, we determined to be left all alone in Athens (διὸ μηκέτι στέγοντες εὐδοκήσαμεν καταλειφθῆναι ἐν Ἀθήναις μόνοι). Paul changes direction and returns to the details of his and Silas’s enforced absence. The chapter division here is not ideal, since the apostle simply reverts to the original point in 2:17–18 after the parenthetical 2:19–20. With “and so” (διό) Paul continues to recount their abortive trip to Thessalonica. He uses in 3:1–2 the first person plural (Paul and Silas), whereas he will go to the first person singular in 3:5 (see comment on 2:18). “When we could stand it no longer” (μηκέτι στέγοντες) is a verbal participle, connected with the indicative “we determined.” It could be construed as causal (“because we could stand it no longer”), but the whole tenor of the section is the chronology of their actions, yielding a temporal participle “when.”

“We determined” (εὐδοκήσαμεν) is the same verb used in 2:8 with regard to giving their very selves to the Thessalonians. In the face of a satanic impediment, the apostles did not complain, nor were they paralyzed. They made hard and pragmatic choices, “to be left all alone in Athens,” while Timothy went to do what was possible. Paul has already spoken of their being orphaned from the Thessalonians, and so “all alone” brings out the poignancy of their situation. We note here again that Acts does not hint at Silas’s being with Paul in Athens, nor of the two of them together making plans to send Timothy to Thessalonica.

3:2a-c And we sent Timothy, our brother and God’s coworker in the gospel of Christ (καὶ ἐπέμψαμεν Τιμόθεον, τὸν ἀδελφὸν ἡμῶν καὶ συνεργὸν τοῦ θεοῦ ἐν τῷ εὐαγγελίῳ τοῦ Χριστοῦ). “And we sent” is the follow-up to “we determined” in 3:1. If the Thessalonians were hoping for the triumphal return of the apostles, they had a letdown: only Timothy showed up.

Timothy is not only their “brother” but also “God’s coworker” (συνεργὸν τοῦ θεοῦ) in the gospel. Other NT passages refer to coworkers in the horizontal sense of one’s fellows in the work (e.g., Timothy himself in Rom 16:21; cf. also the plural in 1 Cor 3:9). Many manuscripts smoothed what they saw as a theological difficulty by emending to “servant of God and our coworker” (διάκονον τοῦ θεοῦ καὶ συνεργὸν ἡμῶν). This is almost certainly an intentional emendation, since the copyists tended to balk about statements about “synergy” with God.

The solution lies not in altering the text but in a correct understanding of working with God. One must imagine that God’s power is possible only through the working of the apostolic team. It is that the team is working along with God, who ensures that the “word” of preaching is not mere talk but the conduit of the divine power (1:5). Paul’s underlying point is: Let no Thessalonian voice disappointment that the apostles themselves had not visited them! They must acknowledge that Paul and Silas have not simply dispatched a messenger boy; Timothy is a true part of the apostolic team, and he too can minister to their needs in God’s power.

A round trip from Athens to Macedonia would have taken three or four weeks, not to mention the time that Timothy spent with the church. This event was a momentous step in Timothy’s experience. He was probably in his early twenties and had only a few months earlier joined the team as the junior member (Acts 16:1–5). Yet here he is carrying out a solo mission to dangerous Thessalonica, one that would end in triumph. He would repeat that success on other occasions (Acts 19:22).

3:2d-f To strengthen you and encourage you for the sake of your faith (εἰς τὸ στηρίξαι ὑμᾶς καὶ παρακαλέσαι ὑπὲρ τῆς πίστεως ὑμῶν). Timothy went north not simply to gather information, but to carry out apostolic ministry. “To” (εἰς τό + infinitive) can denote a result; in this context what follow are infinitives of purpose.14 With “to strengthen you” (εἰς τὸ στηρίξαι ὑμᾶς), Paul employs a verb that he uses four times in these two letters (here; 1 Thess 3:13; 2 Thess 2:17; 3:3). This is a typically Pauline approach in 1 Thessalonians: the disciples are doing well, and the apostles want them to grow even more. Timothy will “encourage” them (παρακαλέσαι) “for the sake of your faith.” “Faith” (πίστις) in this paragraph, as in 1:3, is their active trust in God as tested by hard circumstances. Through Timothy’s work, the Thessalonians will have a stronger confidence in the Lord.

3:3a Lest in some way you had been shaken by these afflictions (τὸ μηδένα σαίνεσθαι ἐν ταῖς θλίψεσιν ταύταις). Now we know why Paul and Silas were unable to stand it any longer (3:1)—they thought that the church might have suffered real damage during the time of the satanic blockade. Paul begins with a phrase that is not easily translated; “lest in some way” (τὸ μηδένα) is acceptable and points to a shaking up that might have occurred before Timothy’s arrival. The implied subject of “been shaken” (σαίνεσθαι) is the Thessalonians, “lest [you] being shaken.” “Shaken” (σαίνω) is a hapax legomenon in the NT, a word more at home in poetic Greek. Its literal sense was of a dog wagging its tail. By extension, it was used of humans fawning on others in order to gain favor.15 Some therefore read the verse to mean that the Thessalonians had been confused by some smooth talker.16

Nevertheless, the other meaning offered fits more neatly here: “to cause to be emotionally upset, move, disturb, agitate.”17 Satan was pressing upon them with “by these afflictions” (ἐν ταῖς θλίψεσιν ταύταις); and there is no evidence that he was using flattery as such as one of his weapons. “Afflictions” here and the cognate verb “afflict” (θλίβω) in 3:4 were commonly used to denote Christian tribulation in general (in 1–2 Thess; Rom 5:3; 8:35; Phil 1:17), or semitechnically, of the eschatological tribulation (Matt 24:21; 24:29; Rev 7:14; but never in Paul).18

Seyoon Kim offers a detailed analysis of Paul’s “entrance” into Thessalonica. When he comes to this shaking up of the Thessalonians, he concludes that the devil must have created doubts specifically about the apostles’ integrity. That is, since Paul speaks about integrity in 2:1–12, he must be touching on the very point that at issue.19 Kim’s argument fails to convince, since in this verse, it seems to be persecution in general that is “shaking” the believers’ faith.

3:3b–4b And in fact, you yourselves know that we were destined for this very thing, because even when we were with you, we told you that we would be put through [such] afflictions (αὐτοὶ γὰρ οἴδατε ὅτι εἰς τοῦτο κείμεθα·καὶ γὰρ ὅτε πρὸς ὑμᾶς ἦμεν, προελέγομεν ὑμῖν ὅτι μέλλομεν θλίβεσθαι). Again Paul uses elaborate “reminder language.” He had taught the Thessalonians not only that tribulation was a possibility, but that it was the Christian’s destiny. The implied subject of “you know” (οἴδατε) is strengthened to “you yourselves” with the intensive use of the pronoun “yourselves” (αὐτοί). They know that “we” (in the sense of “we Christians”) are “destined for this very thing” (εἰς τοῦτο κείμεθα). This passive verb implies “God” as the doer of the action. Paul did not simply observe the harsh realities of pagan Macedonia and calculate that the Christians would be at risk. According to the worldview throughout the NT, God has destined the Christians for trials in this world.

Paul hearkens back to their previous knowledge, drawing on the team’s teaching in Thessalonica. The temporal clause “when we were with you” (ὅτε πρὸς ὑμᾶς ἦμεν) shows the context of when they taught. He reiterates his teaching, using the infinitive of the verb “afflicted.” It would be unjust to the context to load more meaning on the statement than Paul intended, to make it say that “we the church are going to pass through the eschatological tribulation.” Rather, the Christian per se is a person who can expect trials from the world.

3:4c-d Just as it took place, as you know (καθὼς καὶ ἐγένετο καὶ οἴδατε). Paul has circumscribed a large circle: you saw us experience tribulation, you became imitators of us, we foretold tribulations for you, they came about, you know this full well, I’m telling you that you know this, and now we’re all aware of what is going on. With this comparative clause Paul uses “as” (καθώς) to give the Thessalonians a firm reminder of their experience: it has taken place and they know it. “Took place” (ἐγένετο) refers to events of which the Thessalonians are daily all too aware; thus Paul again uses standard reminder language.

3:5a-b And so, when I could stand it no longer, I sent to find out about your faith (διὰ τοῦτο κἀγὼ μηκέτι στέγων ἔπεμψα εἰς τὸ γνῶναι τὴν πίστιν ὑμῶν). Paul seems to hop from topic to topic. He now leaves off speaking about his anxiety and his previous teaching; now he gets back to the main theme: what of Timothy’s mission (3:2)? “And so” (διὰ τοῦτο) returns us to the decision that Paul and Silas took. Yet here, Paul replaces the “and so, when we could stand it no longer … we sent Timothy” (3:1–2) with the first person singular: “when I [myself; κἀγώ] could stand it no longer.” Paul “sent” Timothy (πέμπω, repeating a key verb from 3:2). Years later, Timothy would go on a similar mission to Macedonia to communicate details about Paul and gather information about the church in Philippi (Phil 2:19, 23).

3:5c-d Wondering whether the tempter had perhaps tempted you and our labor had been in vain (μή πως ἐπείρασεν ὑμᾶς ὁ πειράζων καὶ εἰς κενὸν γένηται ὁ κόπος ἡμῶν). Here is the source for Paul’s angst: If Satan was blocking the apostles from entering Thessalonica, what dark deeds might he be doing behind those drawn curtains? After all, their tribulation was not just from angry synagogue leaders or impulsive Gentiles, but was orchestrated by Satan. Their doubt is expressed in “lest perhaps” (μή πως), which we paraphrase as “wondering whether.”20 Paul has a deep sense of apprehension. The following verb is subjunctive to denote the consideration of a possibility.21 “Test, try” (πειράζω) in the context of satanic work means to “entice to improper behavior, tempt” (see BDAG). The verb appears twice here, first as an indicative and then as “the tempter,” a substantival participle (see parallel in the temptations of Jesus, Matt 4:3).

The reader must push through the whole sentence in order to capture Paul’s meaning. It is not as if the apostles were uncertain whether Satan had tempted them—of course he had. Rather, they wondered whether, as a result of that temptation, their apostolic labor might have come to nothing. “Had been in vain” (εἰς κενὸν γένηται) is rhetorically parallel to 3:3, “shaken by these afflictions”; nevertheless it goes further than “shaken,” since Paul seems to imply that the whole Thessalonian project could have failed (for more, see below).

There is a biblical basis for his language. Paul elsewhere applies Isa 49 to his work among Gentiles (Isa 49:6 in Acts 13:47), and it is probable that he is now thinking of Isa 49:4 (KJV)—“Then I said, I have laboured in vain, I have spent my strength for nought, and in vain: yet surely my judgment is with the Lord, and my work with my God.” Paul and the team wondered if in the end their work in Thessalonica had been a waste of time. They knew from the prophet Isaiah that failure was an option.

There are broader questions that must be addressed if we are to understand the team’s apprehensions. First is the psychological. How can they have reconciled their deep unease with other biblical truths, in particular Matt 6:25 (“do not be worry about your life”) or Phil 4:6 (“do not be anxious about anything, but in every situation, by prayer and petition, with thanksgiving, present your requests to God”)?22 The answer lies in what motivates the anxiety. On the one hand, Jesus told his followers not to be anxious about their own daily needs, since this demonstrated a failure of confidence in God. The remedy is prayer and trust. On the other hand, love for one’s fellow Christians could produce a righteous anxiety, especially when they are in distress. A proper course of action would, of course, include prayer—and no one could fault Paul and his team with neglecting that—but also deep concern and the desire to rush to the aid of the needy. This is what we see in 1 Thessalonians. Paul emulates Moses, the prophets, and the Lord Jesus himself. The opposite of this positive, loving type of anxiety would be lukewarm indifference.

The second point of interest is the soteriological. Had Paul genuinely feared that the Thessalonians might have defected because of Satan’s onslaught? We say “defected,” that language being preferable to “lost their salvation.” In this letter, salvation is eschatological, and one cannot lose what one does not yet have. Those who turn from God under Satan’s onslaught are said to “be shaken” (2 Thess 2:2–3), or they might fall away (2:3), or in terms of 1 Thess 1:9, they might turn away once more from the living God.23

Here are some points to consider. Paul gives no hint that his fear is purely hypothetical. In that case he could have said: “We feared lest our work was in vain (which we all know cannot really happen).” Sometimes exegetes point to the conditional or hypothetical nature of a sentence (notably Heb 6:4–6) or the subjunctive mood of the verb in this sort of context and argue that the idea of defection is purely speculative and not a real possibility. But this is simply not how the Greek language works.

Paul and the team were deeply fearful. Fear results from what might really happen, not from what cannot happen and is only hypothetically possible. Their anxiety is not due to some mere abstract conjecture.

Paul does not say that their work would end in vain because Satan would have killed the Thessalonian believers or dispersed the church. It is “temptation” that is said to result in disaster—that is, the believers caving in under Satan’s onslaught and becoming shipwrecked in their faith.

Nevertheless, Paul also indicates that God’s chosen cannot be led away by the Man of Lawlessness, in that ultimate and most insidious deception of Satan in the end times (2 Thess 2:10–12; cf. 1 Thess 5:4, 9). This teaching seems to be drawn from the Olivet Discourse (Matt 24:24: “For false messiahs and false prophets will appear and perform great signs and wonders to deceive, if possible, even the elect”).

Finally, the apostles’ concern for the Thessalonians was eventually eliminated through eyewitness observation. They were able to conclude that “the welcome we had from you was not without good results” (2:1) because Timothy had just reported that the church was still alive and thriving (3:6). In addition, they had heard about their faith indirectly from others (1:7–8). That is, their relief is grounded on hard evidence.

To conclude, Paul and Silas trusted that God would protect the chosen ones; they suspected, rightly, that Satan was trying to pulverize the Thessalonians; they did not know the outcome of that battle until they had evidence as reported by Timothy and others.24 Any doctrine of perseverance must take all of these truths into account. Yet Paul’s concern here is not one of systematic theology (“what could happen?”) but a pastoral one (“what has happened/is happening?”). He is a model of Jesus’ teaching, that one may discern a person’s inner life only by outward manifestations (“fruit,” Matt 7:16), not by guessing about what lies hidden beneath the surface.

3:6a But just now Timothy has come to us from you (Ἄρτι δὲ ἐλθόντος Τιμοθέου πρὸς ἡμᾶς ἀφ’ ὑμῶν). Upon this verse turns the epistle; everything hinged on Timothy’s arrival in Corinth and the news he brought. The conjunction (δέ) is “but,” since this verse stands in contrast to the anxiety that went before. For this reason too “now” (ἄρτι) is better rendered with the more vivid “just now.”25 “Timothy has come” (ἐλθόντος Τιμοθέου) is a genitive absolute, as is “has announced” (εὐαγγελισαμένου).26 By switching from finite verbs and adverbial participles to this new form, Paul introduces a change of rhythm in order to arrest the audience’s attention. “To us from you” indicates that Silas and Paul were together when Timothy arrived; only Acts indicates that Paul and Silas had ever been separated during this portion of the journey.

3:6b-d And has announced the good news of your faith and your love (καὶ εὐαγγελισαμένου ἡμῖν τὴν πίστιν καὶ τὴν ἀγάπην ὑμῶν). Paul has now taken us full circle: Timothy is reporting the information that Paul assumes at the beginning of the letter, that the Thessalonians are still there and that they have faith and love (1:3). “And has announced the good news” (καὶ εὐαγγελισαμένου ἡμῖν) is the second genitive absolute. The word broadly means “announce good news” and not necessarily “evangelize.”27 The good news is that the Thessalonian place of assembly is not some Ground Zero that Timothy gazed on in horror, but a thriving body of believers.

3:6e And that you maintain a good memory of us at all times (καὶ ὅτι ἔχετε μνείαν ἡμῶν ἀγαθὴν πάντοτε). Not only are the Thessalonians still followers of Christ; they are also continuing to be loyal to the missionary team. “At all times” (πάντοτε) and “memory” (μνείαν) sound similar to the prayer language Paul used in 1:2–3 (also Rom 1:9; Eph 1:16; Phil 1:3–4; Phlm 4); nevertheless, it is not prayer language here. But neither does it speak of mere warm feelings, that they had “pleasant memories” of Paul and his team (so the NIV).28 A good translation would be “maintain a recollection.” It refers to maintaining and practicing a teacher’s model or pattern by the disciple, a dynamic that is strongly present in this letter as well as in Hellenism and Judaism. “A disciple continued to be guided by the exemplary life of his teacher in his absence by remembering him.”29 The implication is: “you maintain a good memory of us always and use that mental picture as a guide for your own actions.”

3:6f-g And that you long to see us just as we also long to see you (ἐπιποθοῦντες ἡμᾶς ἰδεῖν καθάπερ καὶ ἡμεῖς ὑμᾶς). The Thessalonians deeply miss the people who, from one perspective, were the proximate cause of their trials. They continue to reciprocate the feelings and motives of the apostolic team. The team was thwarted from seeing the Thessalonians by Satan (2:17–18), and the Thessalonians too wish to see “us.” Paul does not let the parallel go unnoticed. In the NT, the verb “long to” (ἐπιποθοῦντες) is found only in Paul (see 2 Tim 1:4) and James 4:5 and 1 Pet 2:2. Timothy has disclosed that the friendship between apostles and Thessalonians is a mutual one (cf. also Rom 1:11–12).

3:7 And in that way we are encouraged about you, brothers and sisters, in the middle of our affliction and distress, because of your faith (διὰ τοῦτο παρεκλήθημεν, ἀδελφοί, ἐφ’ ὑμῖν ἐπὶ πάσῃ τῇ ἀνάγκῃ καὶ θλίψει ἡμῶν διὰ τῆς ὑμῶν πίστεως). Paul and Silas are experiencing further trials of their own, but if the Thessalonians are well, then “in that way” their spirits are lifted. Once more Paul uses the verb “encouraged” (παρεκλήθημεν). Among Christian friends there is mutual support: Timothy encourages the Thessalonians (3:2), and Paul and Silas are encouraged to hear of them (see also Phil 2:19). “Brothers and sisters” (ἀδελφοί) captures the listeners’ attention and also underlines the fact that they have a shared experienced: Paul and Silas too need encouragement in their times of trial.

The fact of apostolic suffering was a pattern for all Christian tribulation: you saw us suffer, now you suffer, and we too are continuing to suffer. “Affliction” (ἀνάγκη) and “distress” (θλίψις) are often seen together in the LXX.30 In the NT, “affliction” (ἀνάγκη) may refer to an eschatological tribulation (Luke 21:23) or, as here, to the ongoing distresses of Christians during this age (cf. 1 Cor 7:26; 2 Cor 6:4; 12:10).

It is not clear to which trials the apostle is now referring. Is it the persecutions in Macedonia, some unnamed distress in Achaia, or simply the apostolic trials in general? Regardless, it is “because of your faith” (διὰ τῆς ὑμῶν πίστεως) that Paul and Silas have received encouragement. The phrase has specific reference to the positive news that Timothy has brought (1:3).

3:8 That’s because, now we are alive if you stand firm in the Lord! (ὅτι νῦν ζῶμεν ἐὰν ὑμεῖς στήκετε ἐν κυρίῳ). Paul tends to repeat himself when he is emotionally moved, and so he states the obvious once more. We take the conjunction (ὅτι) as the marker of a causal clause, explaining why Paul can say they are encouraged in 3:7. For them to “live” is not physical life, but a life of joy. Some translations offer some version of “now we really live.” “Stand in the Lord” uses a typically Pauline verb, “to stand” (στήκω); it has the sense “to be firmly committed in conviction or belief” (so BDAG).31 Paul will exhort them later to “stand” in 2 Thess 2:15, using the imperative mood: “be firmly committed [στήκω] and hold tight to the traditions that you were taught.”

3:9 What kind of thanksgiving can we repay God concerning you because of all the joy with which we rejoice on account of you before our God? (τίνα γὰρ εὐχαριστίαν δυνάμεθα τῷ θεῷ ἀνταποδοῦναι περὶ ὑμῶν ἐπὶ πάσῃ τῇ χαρᾷ ᾗ χαίρομεν δι’ ὑμᾶς ἔμπροσθεν τοῦ θεοῦ ἡμῶν). Paul’s rhetorical question comes across as more powerful than his declarations of gratitude. Certainly, he and Silas give thanks to God, but what kind of thanksgiving could possibly be sufficient?

The emotion continues to build. They rejoice before God because of the joy the Thessalonians have given them! The use of the cognate words “joy” (χαρά) and “rejoice” (χαίρω) are like the language of Hebrew poetry, which tends to use pairs of cognate words in order to emphasize a deep truth. Since this sort of repetition does not function well in English, “rejoice with joy” is not the best rendering. The NIV does better with, “for all the joy we have.” “Before” (ἔμπροσθεν) is again prayer language as in 1:3, standing before the God who is always present for Christians.

3:10a-d Unreservedly, night and day we are asking [God] to be able to see you in person (νυκτὸς καὶ ἡμέρας ὑπερεκπερισσοῦ δεόμενοι εἰς τὸ ἰδεῖν ὑμῶν τὸ πρόσωπον). Paul’s language swells. Now he gives a prayer report to show what is an appropriate response to this spiritual feeling. This is still technically a part of the rhetorical question that began in 3:9, but we have broken it up in order to make it smooth English. As in 2:9, he uses the genitive “night and day” (νυκτὸς καὶ ἡμέρας) to denote “by night, by day.” “Asking” (δεόμενοι) is a participle connected with “we rejoice” (χαίρομεν) in 3:9; their rejoicing is ever yoked with the “unceasing” prayer of which this letter is so redolent.

Up to this point the prayer language is familiar from other letters; but it is the term “unreservedly” (ὑπερεκπερισσοῦ) that gives the translator pause, since the compounded adverb is hard to render into proper English. BDAG offers “quite beyond all measure (highest form of comparison imaginable)”; L&N 78.34 suggests “extreme earnestness.” These are fine as far as they go, but they sound tamer than the original. The expression “flat out” would capture Paul’s mood, but is too idiomatic. Hence we have chosen “unreservedly.”

Paul and Silas are petitioning God with εἰς τό, which shows the goal of their prayer.32 At last we see what this team is praying for: that they might see the Thessalonians. As in 2:17, he uses an expression for a face-to-face meeting (τὸ πρόσωπον ὑμῶν) to refer to a personal visit. But beyond that, implicit in their prayer is that the satanic obstacle might prove to be no hindrance at all, that Paul and Silas will be able to once again head north and not simply send their agent to spy out the land. This prayer report should be studied in tandem with 2:18. Satan can seek to block the apostles, but lying behind that action, God has given him permission to do so. Thus the solution is not to rebuke Satan or to calculate boundaries of a territorial spirit, but to go directly to God and ask him to alter circumstances.

3:10e-f And to put in order any things that are lacking in your faith (καὶ καταρτίσαι τὰ ὑστερήματα τῆς πίστεως ὑμῶν). To be sure, this letter was already designed to fill the gaps in their lives, particularly in 4:13–18. Beyond that, Timothy was acting as the apostolic envoy who knows how to strengthen them. But Paul and Silas wish to do the same, and in person. “To put in order” (καὶ καταρτίσαι; BDAG suggests “to fix up any deficiencies”) is the second concern. With “lacking in your faith” (τὰ ὑστερήματα τῆς πίστεως ὑμῶν) Paul does not distinguish between faith as “doctrine” and faith as “practice”; likely in this statement, the one blends into the other.

Timothy would go north with 1 Thessalonians, then return to Corinth; Paul would then write the second letter and send it with Timothy. From that point until Paul’s return to Macedonia on his third missionary journey, we know little of these believers. The data we have suggest that Silas would go to Macedonia, but apparently not to Thessalonica (Acts 18:5). Thus, neither Paul nor Silas would be able to revisit Thessalonica for six or seven years more, perhaps at the time of the writing of 2 Corinthians. We do not know if Satan kept blocking them or if, as in Ephesus, “a great door for effective work” (1 Cor 16:9) had opened to them in Corinth and other locales, and they were loathe to leave. Green states that God answered the apostles’ prayer, pointing to Acts 19:21–22, where Paul again passed through Macedonia.33 This is stretching a point, since many years would pass before that next visit. The better interpretation is that God did not immediately answer their prayer.

3:11a-b Now may our God and Father himself and our Lord Jesus (Αὐτὸς δὲ ὁ θεὸς καὶ πατὴρ ἡμῶν καὶ ὁ κύριος ἡμῶν Ἰησοῦς). With “now” Paul concludes this section. The words Paul dictates are at once a real prayer and also an exemplar of the apostles’ prayers for the Thessalonians.

Grammatically the verbs (see below) catch the eye. The optative mood (as in “may God do something”) was rarely used in the first century. The spread of koinē Greek since the third century BC meant that many of the finer classical usages were left behind as Greek became an international second language. As part of this evolution, the optative was in “strong retreat.”34 It was being subsumed into the subjunctive and is virtually extinct in modern Greek. In the LXX it occurs in nearly four hundred verses, but in the New Testament only sixty-eight times. Paul uses it twenty-eight times; his stereotyped “Never!” (μὴ γένοιτο; lit., “may it not be”) accounts for fourteen (ten times in Romans alone, three times in Galatians, once in 1 Cor 6:15).

Apart from that, many are “voluntary optatives,” used “to express an obtainable wish or a prayer.”35 This appears three times in this prayer: “direct” (κατευθύναι), “increase” (πλεονάσαι) and “abound” (περισσεύσαι) in 3:11–12. What is remarkable for our purposes is the high frequency of nine optatives in the Thessalonian letters.36 The fact that the LXX Psalms used the optative in prayer may have prompted Paul to use this antiquated form, because it sounded like “biblical” prayer language.

“Our God and Father himself” (αὐτὸς δὲ ὁ θεὸς καὶ πατὴρ ἡμῶν) is not a common phrase, but “God himself” is found again with an optative in 1 Thess 5:23 (cf. also Rev 21:3).37 Isaiah 54:5 LXX provides a parallel with this letter: “he who rescues you is the God of Israel himself” (pers. trans.; 54:4 MT).

Integral to the apostle’s theology is that Paul prays to the Lord Jesus just as he prays to the Father. He does not defend or justify the practice. We can only assume that the new disciples had heard him praying to God the Father and to the Lord Jesus from the very first. There is syntactical tension here that reveals something of his theology; technically there is disagreement between the plural subjects “our God and Father and our Lord Jesus” and the singular verbs of which they are the subject. In English we would have to imagine a sentence such as “God and Jesus directs us” in order to hear the same grammatical discord. It is common in the Pauline literature to see Jesus assume many of the roles of God.

3:11b Direct our steps to you (κατευθύναι τὴν ὁδὸν ἡμῶν πρὸς ὑμᾶς). The Lord of the angelic hosts can break the satanic blockade whenever it pleases him so to do. And so the team prays about a concrete aspect of their ministry, the possible return north of the full apostolic team. The verb “direct” (κατευθύναι) is a common one in the Jewish literature.38 This is a prayer that God will give them “clear passage.”

3:12a And may the Lord make you to increase and abound (ὑμᾶς δὲ ὁ κύριος πλεονάσαι καὶ περισσεύσαι). Paul goes on to pray for the Thessalonians themselves, using two optatives from the verbs “increase” and “abound.” The subject of the verb is “the Lord,” the referent of which is consistently the Lord Jesus in these two letters. Jesus is not simply some powerful angel who, like Michael in Dan 10:13, 21, can make a show of power; here he does what only God does, working deep within the hearts of his people to incline them toward righteousness. “Increase” (πλεονάζω) is used of the abounding of Christian virtue in 2 Thess 1:3 and 2 Pet 1:8. Paul uses the language of “abounding” or “thriving” here and in 1 Thess 4:1, 10 to affirm that the disciples are on the right path and to pray for or encourage further growth. As prayer was pivotal in bringing about their conversion, so it is in their growth.

3:12b-c In love for one another and for all people (τῇ ἀγάπῃ εἰς ἀλλήλους καὶ εἰς πάντας). Just as they are already renowned for their love (1:3), so now Paul prays that they grow still more. “One another” is the language used in a broad set of reciprocal actions within the Christian community.39 “And for all people” could refer to Christians of other communities (see 1:7), but a better rendering is a reference to love they have for “the whole human race” (JB).40 Their love for outsiders and their desire to take the gospel to them contrasts with the forbidding stance of the synagogue toward the Gentile nations (2:15–16).

Here may be a veiled reference to the Olivet Discourse: apostates will “hate each other” and “the love of most will grow cold” (Matt 24:10, 12). By maintaining their love—no, by abounding in love—the Macedonians are standing firm against apostasy, whether it is the end time or not. The author of 2 Clement may have had either Matthew or 1 Thessalonians in mind when he urged his audience, “let us love one another, that we all may enter into the kingdom of God” (2 Clem. 9.6); he understood that those who are worthy of the kingdom are loving. Paul will next speak of love in 1 Thess 5:8, of the breastplate that is love. It is right to pray that others may be more loving and to expect that the glorified Lord Jesus—preacher of the Olivet Discourse—might answer that prayer.

3:12d Just as our love does for you (καθάπερ καὶ ἡμεῖς εἰς ὑμᾶς). All of 1 Thess 2–3 has shown the apostles’ love in the feelings they express, but more importantly, in the actions they have taken. He reminds the disciples that they have an excellent model of mutual love in the apostolic team; once again, Paul and his team are the “pattern” the disciples should imitate.

3:13a-b So that your entire person be made strong in blamelessness, [that is] with regard to holiness (εἰς τὸ στηρίξαι ὑμῶν τὰς καρδίας ἀμέμπτους ἐν ἁγιωσύνῃ). Paul now orients his readers toward the parousia; their present behavior will affect how they stand before God in his judgment. “So that” (εἰς τό) leads to an infinitive of result. The NIV, NRSV, and NJB start a new sentence and make the infinitive “strengthen” (στηρίξαι) sound as if it too were an optative (“May he strengthen your hearts so that … ,” NIV), but this is to neglect the causal relationship between growing in love and being strengthened in holiness. The NLT is better: “May he, as a result, make your hearts strong….” “Strengthen” (from στηρίζω) described Timothy’s work among them in 3:2; his ministry has its counterpart in the spiritual realm when the apostles pray toward the same end. “Hearts” (τὰς καρδίας) is not a reference to the emotional life, but to the whole inner person (cf. 2:4).41

Their “blamelessness” (ἀμέμπτους) may be summed up as perfect “holiness” (ἁγιωσύνη; cf. the other references in Rom 1:4; 2 Cor 7:1). God’s will in 1 Thess 4:3 is represented by the cognate “holiness” or “sanctification” (ἁγιασμός). Paul prays at the end of the letter for this very point, that they will be holy and ready at Christ’s return (5:23).

3:13c-d Before our God and Father, at the coming of our Lord Jesus (ἔμπροσθεν τοῦ θεοῦ καὶ πατρὸς ἡμῶν ἐν τῇ παρουσίᾳ τοῦ κυρίου ἡμῶν Ἰησοῦ). Again we return to eschatology: here, as in 2:19, “before” (ἔμπροσθεν + genitive) refers to the parousia or the judgment. The saints will stand before “our God and Father” in the coming of Jesus. This statement has implications regarding the person of Christ, especially when Paul’s Christology is contrasted with the theology of Second Temple Judaism. Within the Jewish hope, the messianic figure may range from being a central eschatological person to being eliminated entirely; or there may be two or even three messiahs.

But Christian theology is christocentric in a way that Judaism has never been Messiah-centric.42 In Judaism, the Messiah does not mediate the presence of Yahweh as Christ does for God; he certainly does not fulfill the scriptural predictions of the epiphany of Yahweh.43 In 3:13, Paul goes even beyond Matt 16:27: “For the Son of Man is going to come in his Father’s glory with his angels.” Jesus does not simply gather the saints to the Father; he embodies God’s presence by his own person.

3:13e With all his holy [angels]. Amen (μετὰ πάντων τῶν ἁγίων αὐτοῦ. [Ἀμήν]). The Lord Jesus is accompanied by other holy beings in his parousia, but by whom? “All his holy ones” (πάντων τῶν ἁγίων αὐτοῦ) is simple enough syntax: it is the substantive use of the adjective “holy.” There are two major interpretations of these “holy ones.” The first is that they are holy human beings—either saints of the old covenant or Christian saints.44 The second is that they are holy angels.45 A compromise solution is that both human and angelic beings are intended.46

In favor of the interpretation that these are human saints are the many New Testament references to Christians, so much so that “the holy ones” or “saints” (οἱ ἅγιοι) is a semitechnical term for believers.47 It appears that this is the sense of 2 Thess 1:10, which uses a Hebrew-type parallelism:

when he comes to be glorified among his saints and

to be worshiped among all who have believed

This verse does not necessarily contain a reference to Jesus coming with holy ones; rather, the saints glorify and worship him at the point of his revelation.

There is one possible NT picture of Christ coming to earth with human saints, in Rev 19:14: “The armies of heaven were following him, riding on white horses and dressed in fine linen, white and clean.” This interpretation of 19:14 rests on the identification of the armies with saints in 19:7–8: “His bride has made herself ready. Fine linen, bright and clean, was given her to wear. (Fine linen stands for the righteous acts of God’s holy people.).” Yes, they wear fine linen … but then so do angels in Rev 15:6, who are “dressed in clean, shining linen … [with] golden sashes around their chests.” The referent of “the armies” in Rev 19:14 is in the end difficult to pin down.

In favor of the second view, that these are “holy angels,” there exist many references to the coming of Yahweh or the appearing of the Son of Man or the parousia of Christ with angels.48 Deuteronomy 33:2 speaks of Yahweh descending from Sinai: “The Lord came from Sinai and dawned over them from Seir; he shone forth from Mount Paran. He came with myriads of holy ones from the south, from his mountain slopes.”49 In Jude 14, “Enoch, the seventh from Adam, prophesied about these men: ‘See, the Lord is coming with thousands upon thousands of his holy ones.’ ” This is a direct reference to the pseudepigraphal 1 En. 1.9 (ed. Charlesworth): “Behold, he will arrive with ten million of the holy ones in order to execute judgment upon all.” These “holy ones” are angelic, as in 1 En. 60.4; 61.10.

The “clouds” of heaven in Dan 7:13; Mark 14:62; and Rev 1:7 might also denote the heavenly armies. In the Matthean version of the Olivet Discourse, the angels come with the Son of Man in order to collect the elect from the four corners of the earth (Matt 24:31); according to 24:36, these same angels do not know the day or hour of the parousia. Angels are also assigned to gather the wicked together for the fiery judgment (Matt 13:39, 41, 49). Besides all this evidence lies the parallel in 2 Thess 1:7: “the revealing of the Lord Jesus from heaven with his powerful angels” (μετ’ ἀγγέλων δυνάμεως αὐτοῦ). The breadth of the evidence shows that 1 Thess 3:13 refers to angels, as does 2 Thess 1:7 (but they are not mentioned in 2 Thess 1:10).

The referent of “his angels” is not precise: its antecedent may be the Lord Jesus or God the Father. The parallel “his” in Matt 16:27 give no definitive help either; in Mark and Luke, Jesus simply refers to “the” angels. In 3:13, there is an allusion to Zech 14:5 (NETS)—“And the Lord my God will come and all his holy ones with him.” By contrast, in Matt 24:31 the Son of Man comes with “his angels,” and here the pronoun “his” clearly refers to the Son of Man. The parallel in 2 Thess 1:7 also makes the angels belong to the Lord Jesus. The parallels in Zechariah, Matthew, and 2 Thessalonians point to “all the holy angels” of the Lord Jesus. We conclude that Paul is speaking in 1 Thess 3:13 of how the Thessalonian believers will measure up in the presence of God, at the return of Jesus when he comes with his holy angels.

There is a minor textual problem at the end of this prayer, a phenomenon that is encountered at the close of prayers in other letters. Many strong witnesses include an “Amen” (ἀμήν), while other strong ones omit it. It may have been added in the margin by a pious scribe, assuming that it was appropriate conclusion to a prayer.50

Theology in Application

Theology in Thessalonica

Many of the Thessalonians had come to Christ from paganism. Their gods were of superhuman power, but they were bound to the Fates just as were human beings. This meant that no Gentile, no matter how pious, could use prayer to substantially redirect future events; what would be would be. The most that could be hoped for was that the regular sacrifices and visible religious duties would ameliorate some of the excesses of divine caprice, even while one’s Fate rolled on.

When the gospel arrived in Thessalonica, those Gentiles heard, perhaps for the first time, that there might exist a “living and true” God (1:9), one who freely “chose” (1:4) and who was in no way bound by Fate. This made stunning changes in the way in which the new believers saw the universe. Instead of fear and fatalism, believers could turn to the true God for help, even during hard circumstances, and ask for circumstances to change with regard to something as mundane as travel plans or something as profound as spiritual growth. “The God to whom we pray is no pitiless deity … but is the Father who can do all things, has control of every situation and is near me in every time of need.”51 The fact that Paul thanks this God for the blessings that have happened also indicates that God is their source and that he is not simply a bystander to Fate.

Biblical Theology

For the Christian, prayer is entering into a personal relationship with the almighty God through his Son Jesus Christ.

Satan, too, is a reality in the Christian life. While many Western Christians reject the idea of a personal evil being,52 it is a part of the apostolic gospel that he exists and that he makes himself known by trying to harm the gospel work—at times successfully—by blocking plans or by harming believers. Paul understands that to rightly exegete one’s circumstances, we cannot relegate what happens to mere happenstance. By contrast, the believer who does not have direct access to a prophetic word from God must show great care in ascribing this thing to Satan or that thing God, lest he or she make a disastrous mistaken identification.

Paul asks God that their faith be strengthened (3:10), but the apostle does not let up on his own efforts toward achieving that end. Neither did he know anything of “follow-up” as a brief period of instruction after a person makes a profession. Another modern notion is that once a person makes a profession of faith in Christ, it is up to the Holy Spirit to preserve them, and the evangelist’s work is done. That is, if they are true Christians, they will survive; if they do not persevere, it must not have been the real thing. The Bible reader seeks in vain for this sort of laissez-faire discipleship. Rather, urgency is the key characteristic of Paul’s work in taking his disciples from conversion through maturity. At every stage, prayer is a nonnegotiable.

By putting an imaginative spin on the apostolic prayers in this and other letters, we might be able to picture Paul and his companions at prayer:

Setting: One evening in Corinth before the sending of 1 Thessalonians

Paul: Our God and our Father, our Lord Jesus, our hearts are full of thanks. You have given us spiritual children, Father. It was you who sent the Spirit to convert them from their false idols. We did not do that, Lord, but you intervened and chose out for yourself a people for your name.

Silas: God and Father, you have made us love them. And they love each other so much. Miriam was even shunned by her parents because she refused to give up her new Christian friends. Be a Father to her, Savior; let the church embrace her as their own sister.

Paul: Be with those who can’t find work because of their faith; we don’t even know who they might be in this very hour. Let no one be discouraged, Lord, but let them seek work and find it so that they can support themselves in a godly way.

Timothy: Samuel was beaten in the synagogue, Lord Jesus, and did not deny your name. May all Christians of Thessalonica follow you even as they learn that this is normal for those who follow you.

Silas: Let no one panic, Lord, or lose hope. May everyone endure. [He prays at length and mentions many by name].

Paul: Thank you so much, Father, for these young disciples. [He too prays for dozens of individuals and mentions details about a number of them]. You’ve planted deep within us the desire to nurture them. But now you have placed us so far away, and we can only reach them in writing. For so many weeks Satan has blocked us. May it please you, Father … [he tears up and cannot speak].

Silas: Lift Satan’s blockade, we petition you, O Lord. No power in heaven or on earth can defy you. We confess that the Thessalonians are in your care; Timothy has brought us a good report; but in your mercy we pray that you would let us see the church with our own eyes.

And so on and so on…

Message of This Passage for the Church Today

One is impressed with the holy activism of the Pauline team through this section. If we were to follow the apostolic pattern laid down here, we would warn our people of all the possibilities that lie ahead, just as the apostles were frank about the possibility of persecution. In Greek mythology, Cassandra was a prophetess who foresaw horrible events, only to suffer the curse of being disbelieved. The apostolic message is more positive, given that we depend not on the Fates but on the almighty God.

Nevertheless, do we as preachers prepare our flocks for hard times? It’s more of a crowd-pleaser to preach prosperity, conventional morality, how to succeed in business with God on our side, family values, politics, or theology that doesn’t connect with real-life events—such as death, divorce, disease, addiction, unemployment, or rejection. In particular, a faithful Christian will warn people that tribulation is typical of Christianity, not an aberration. With regard to suffering, any pastor today who is not warning the flock about a great false teaching of our day, the Prosperity Gospel, is leaving the door open for trouble.

When speaking about signs of the end, focus not just on earthquakes and rumors of war, but also the grave danger that “the love of most will grow cold.”

A certain proportion of Christians imagine that prayer is not about changing things, but rather changing our attitude about circumstances. Other Christians exaggerate Jesus’ warning against vain “babbling” in prayer (Matt 6:7) and pray once and for all, “leaving it all in God’s hands.” But Jesus was not speaking against continual, fervent prayer, such as we find summarized in 1 Thess 3:10. In Christian prayer, one prays with passion and in communication with a divine Person, aided by the Holy Spirit.

Pray for matters that perhaps, according to your theology, are already sure things. Do you pray for your people? That they will continue to grow and be steadfast? Or even, as Paul implies here, that they will stay Christian? “But I believe in eternal security!” you might answer. Very well, and so do I. But the Holy Spirit carries out his work in part through the prayer of fellow believers.