Chapter 5

1 Thessalonians 4:13–18

Literary Context

In 4:1–12, Paul took up various points of Christian ethics, and he affirms that the Thessalonians already know and practice them. To put it another way, there is nothing that a Thessalonian would have found new or confusing. By contrast, in 4:13–18 Paul helps the believers navigate a topic they have perhaps never heard or, as is more likely, have forgotten to apply in their situation. Thus, 4:13–18 is the only paragraph that contains material new to them: that at his parousia, Jesus will resurrect the dead saints so that they will enjoy his coming with those who are still alive. Then in 5:1, the apostle returns to material that, again, he is sure they well know.

These verses serve to draw together and unite the various threads of eschatological hope: believers in Jesus will escape from God’s wrath (1:10; 5:9; by implication 2:16); they must be holy at Jesus’ coming (3:13; 5:1–11, 23); and they joyfully anticipate the parousia in part because their fallen friends will be there too (4:17–18).

The fact that Paul does not have to explore the topic further in 2 Thessalonians indicates that the matter was settled.

- VI. Paraenesis: The Gospel Ethic in a Gentile Environment (4:1–12)

- VII. Instruction about the Return of Christ (4:13–5:11)

- A. Dead Christians will be raised to be with Jesus ahead of the living (4:13–18)

- B. Christians should live in holiness, even without knowing the timing of the end (5:1–11)

- VIII. Final Exhortations (5:12–22)

Main Idea

For all their strong grip on Christian doctrine (e.g., Jesus doing the work of Yahweh, the person of the Spirit, the work of Satan, Jesus’ death and resurrection), the Thessalonians are missing something essential: that Christ’s resurrection guarantees the resurrection of believers who have died before his return. Most likely Paul had taught that doctrine to them, but in a time of persecution they were forgetting to apply it; we invite the reader to look over the material in the Introduction, under “Eschatology in Thessalonica.”

Translation

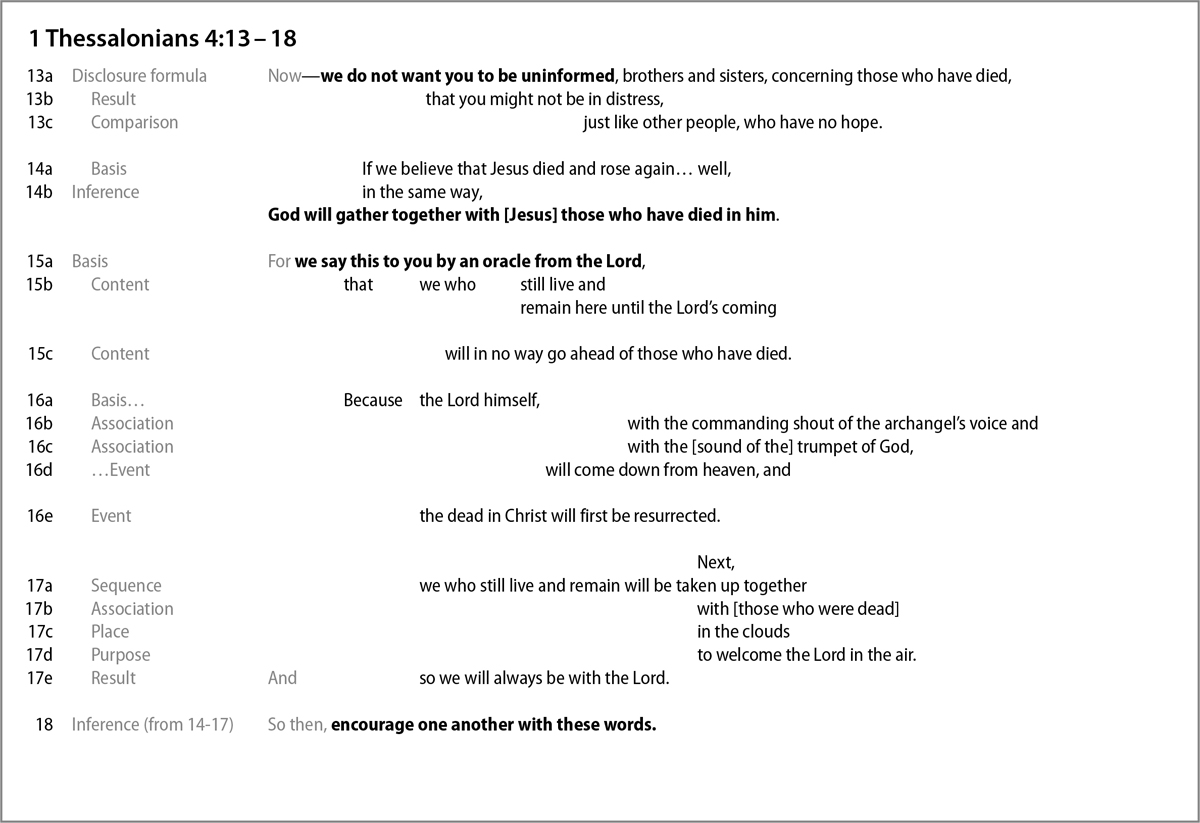

Structure

Paul has already said plenty about the Lord’s return, but now he turns his full attention to eschatology. He uses a litotes, “we do not wish you to be uninformed” to mean “let us fill you in on information you are lacking.” Once the Thessalonians have a proper grasp on the fate of their dead companions, they will not be emotionally distraught. Paul uses comparative language “just like [καθώς] other people” (4:13), in order to draw a firm distinction between the people of hope (see 1:3) and the hopeless pagans. His aim is pastoral, and he knows that good hope is rooted in good doctrine. Thus Paul begins with a word of hope in 4:13, starting an inclusio that will end with his charge to his hearers to comfort one another by means of the same information (4:18).

The Thessalonians’ main problem concerned those Christians who had died (using the common euphemism “fallen asleep”) in contrast with those “who still live and remain here” (4:15). Paul offers two proofs for the eschatological resurrection, a doctrine that will surely boost their spirits.

The first proof is that the resurrection of Jesus provides a full solution to their doubts (4:14). The adverb “thus” or “in the same way” (οὕτως) signals that Paul will be drawing an inference from the protasis: if we believe that God raised Jesus from the dead, then it is safe to assume that God will resurrect believers as well. This act is called a “gathering together with Jesus.” Paul reflects the language of the Olivet Discourse, where the angels gather the elect (Matt 24:31). He also anticipates 4:17e, “so we will always be with the Lord”; and 2 Thess 2:1, God “gathers us together to Christ.”

Paul offers a second proof in 4:15. I will argue in the commentary that this is not a summary of Jesus’ teaching or an agraphon, a hitherto unwritten teaching of Jesus. Rather, it is “an oracle from the Lord Jesus” given through a living communication as prophecy, perhaps recently to Paul or Silas. The content of the message is introduced by “that” (ὅτι, to introduce indirect discourse); it is brief but direct: “We who still live and remain here until the Lord’s coming will in no way go ahead of those who have died” (v. 15).

Paul then begins at the beginning and describes the second coming. It is best to take 4:16–17, not as part of the prophetic oracle of 4:15, but as a summary description of the parousia that uses traditional language of angels and trumpet, but in which the resurrection of the dead is strongly featured. Instead of the angels simply going to gather the saints from the four corners of the earth, which one would expect having heard Matt 24:31, the dead in Christ make a sudden appearance in 4:16e: “and the dead in Christ will first be resurrected.”

Paul then introduces the believers who are still living (4:17). There is a nice contrast between “and” (καί) the dead will rise, “next” (ἔπειτα) the living. One might almost paraphrase it as “only then will the living be taken up.” They will rise to be with the resurrected dead; the resurrected believers once again serve as a point of reference, if at some moment we had forgotten that they had already been made alive. It will all happen “so” (καὶ οὕτως, 4:17e), that is, “in this manner.” There is no need for the sort of grief that their pagan neighbors exhibit (4:13), since every believer will enjoy Christ’s presence forever.

To round out his inclusio in this section, Paul is not simply concerned with informing them about eschatology, but about comforting them and giving them the tools so that they can “encourage one another” (4:18).

Exegetical Outline

- I. The Apostles Perceive That the Thessalonians Are Missing an Important Piece of Teaching and Move to Fill It (4:13).

- II. The Basis for This Doctrine Is Found in the Gospel and Also in New Revelation (4:14–15a).

- A. According to the gospel, Jesus died and rose again; Christians will do the same (4:14).

- B. By a prophetic oracle the apostles have more details that they now transmit to the Thessalonians (4:15a).

- III. The Apostolic Eschatology Reveals Truths Relevant to the Thessalonians’ Confusion (4:15b–17).

- A. At the Lord’s coming, the risen dead will be the first to go to meet Jesus (4:15b–16).

- B. Then the living believers will ascend to join with the resurrected dead in welcoming Jesus (4:17a).

- C. All Christians will be with the Lord Jesus forever (4:17b-e).

- IV. The Benefit of This Doctrine Is to Encourage Living Christians (4:18).

Explanation of the Text

4:13a Now—we do not want you to be uninformed, brothers and sisters, concerning those who have died (Οὐ θέλομεν δὲ ὑμᾶς ἀγνοεῖν, ἀδελφοί, περὶ τῶν κοιμωμένων). Paul appreciates how people learn. He began in 4:1–12 by going over what the Thessalonians already clearly grasped, that is, the familiar themes of sexual purity and brotherly love. He now takes them to an area where they are not clear. To be sure, they have been awaiting Jesus’ coming from heaven (1:10) with his holy angels (3:13); yet they are wondering whether they will see their fallen comrades again at that parousia. Paul uses “now” (δέ) to turn their attention to this new theme and brings them to full attention with “brothers and sisters” (ἀδελφοί). “We do not want you to be uninformed,” he says; as throughout this chapter, “we” means Paul and Silas. The infinitive “to be uninformed” (ἀγνοεῖν) might be rendered “to be or stay ignorant,” but as this has an insulting tone in English, we render it in a way that does not imply criticism. The clause is a typical formula for disclosing new information (see 1 Cor 10:1; 12:1; 2 Cor 1:8).

There are two ways to translate “those who have died” (τῶν κοιμωμένων). The verb in some contexts had first of all the sense of literal sleep. Second, it served as a metaphor, denoting death; its cognate, “sleeping-place” (κοιμητήριον), is the root of the English word “cemetery.” The same double meaning of “sleep/death” occurs in the synonym for “sleep” (καθεύδω). This latter verb is used in Dan 12:2 to speak of the dead who will be resurrected, and Paul will use it in 1 Thess 5:10; probably it denotes “death” there as well.

Sleep came to be a metaphor for death at least as early as Homer: “So there the poor fellow lay, sleeping a sleep [from κοιμάω] as it were of bronze, killed in the defense of his fellow-citizens” (Iliad 11.241, trans. Butler). Homer believed neither in soul sleep nor in the resurrection; therefore, the metaphor does not imply a doctrine of soul sleep or that the person would “awake” at the resurrection. The comparison with sleep has to do with the appearance of the body to the survivors. Some Jewish literature pairs the verb “sleep” (κοιμάω) and resurrection (2 Macc 12:45); thus, Paul is using language that would have been a metaphor about death for Greeks or Jews.1

It is therefore a mistake to render the verb with a supposed literal equivalent, that is, “to fall asleep” (many versions, including KJV, NASB, ESV, NJB; the NIV and REB have “sleep in death”); to his readers it simply meant “to die.” It is parallel to “the dead” (i.e., οἱ νεκροί) in 4:16. Nevertheless, the wordplay between sleep and death does form a part of the plot of John 11:11, where Lazarus is thought by the disciples to be peacefully sleeping off his illness, whereas Jesus meant that Lazarus had died. But only in the postapostolic period did Christians begin to make a regular play on the double meaning of the verbs.

4:13b-c That you might not be in distress, just like other people, who have no hope (ἵνα μὴ λυπῆσθε καθὼς καὶ οἱ λοιποὶ οἱ μὴ ἔχοντες ἐλπίδα). Greco-Roman piety demanded that each family member properly grieve over the loss of a loved one. For their part, Thessalonian Christians have broken with their biological kin and pledged their deepest fidelity to the new family of faith. This leads to the reassigning of the role of “survivors” from blood relatives to members of the church. Are the Thessalonians therefore expected to rend their garments, as they would have done out of respect for their deceased biological parents?

Not precisely, answers Paul, but it is not for any lack of family feeling. Nor are they to follow the lead of the philosophers, who urged that people moderate their grief to a reasonable level. The Christian survivors’ reaction is based on their hope in God. But what is the specific point of contrast in “that you might not be in distress, just like other people.” Is Paul saying (1) that they should not grieve at all, because only those devoid of hope feel grief?2 Or is he saying (2) that they must not grieve in the same manner that the hopeless Gentiles do?3 Almost certainly the second is his intended meaning; “he meant simply to restrain excessive grief, which [grief] would never have had such an influence among them, if they had seriously considered the resurrection, and kept it in remembrance.”4

This interpretation is fitting in light of how grief is handled in other NT passages. One of the most poignant images of sorrow is that of Martha and Mary sitting in mourning for Lazarus; hardly less moving or less significant is that “Jesus wept” on the way to Lazarus’s grave (John 11:35). Yet in 11:24–27, Jesus and Martha both declare their faith in the resurrection. This resurrection hope transforms anguish into sorrow that is moderated by hope. Other examples of godly sorrow include when the Christians “mourned deeply” over the martyred Stephen (Acts 8:2). Sorrow is positively represented in the Pauline letters (e.g., Rom 9:2; 2 Cor 6:10; Phil 2:27). In fact, “the Bible everywhere assumes that those who are bereaved will grieve, and their grief is never belittled.”5 Therefore Thessalonians should not grieve in the unmitigated manner of the hopeless.

Paul compares other people with those “who have no hope.” The church is surrounded on all sides by Greeks. Their funeral rites reflect their belief in the irremediable loss of the loved one. For them, death was, as N. T. Wright puts it, a “one-way street.”6 The author of Hebrews seems to have Gentiles in mind when he refers in Heb 2:15 to “those who all their lives were held in slavery by their fear of death,” an anxiety not readily grasped today when medical science always holds out the hope of yet one more miracle treatment.

4:14a If we believe that Jesus died and rose again (εἰ γὰρ πιστεύομεν ὅτι Ἰησοῦς ἀπέθανεν καὶ ἀνέστη). The hope that Christians have, that which lifts them from utter distress, is made possible only by the death and resurrection of Jesus. The Christian hope is not merely wishful thinking, but a confident expectation. Paul uses “for” (γάρ), which need not be translated into English so long as the causal sense is implied. The function of this protasis (the “if” clause) is not to question whether Jesus’ death and resurrection are true, but to draw a conclusion—if the resurrection is believed to be true (and by definition a Christian does so believe, 1:10), then what follows is also true.7 Paul uses the same sort of logic in 1 Cor 15:12: “If it is preached that Christ has been raised from the dead, how can some of you say that there is no resurrection of the dead?”

“We believe that Jesus died and rose again” is fundamental to the Pauline kerygma. It may seem strange to modern ears that the point that “Jesus died” would be a part of someone’s creed, as if that could ever be debated. Yet that doctrine was precisely in doubt in the Hellenistic world and would later come under fire in Gnosticism. The Greeks had plenty of stories of gods and goddesses who passed among humans in disguise, but who, being immortal, did not die. The Gnostic Gospel of Philip 22 makes Jesus’ death to be spiritual, not literal. Other Gnostics imagined that God miraculously made Simon of Cyrene look like Jesus, so that he was crucified in his place while Jesus watched from the crowd.

Paul for his part makes the point that without Jesus’ death, there is no resurrection of Jesus and hence no hope for the resurrection of the Christian. The Apostles’ Creed affirms this truth with Paul and turns aside the Gnostics with its declaration that Jesus “suffered under Pontius Pilate, was crucified, dead, and buried.” His death was “for us” (5:10). “Rose again” (ἀνέστη) is the typical verb for the resurrection both of Jesus and the saints and is repeated in 4:16. The passage in 1 Cor 15:52 uses another verb to say that “the dead will be raised” (οἱ νεκροὶ ἐγερθήσονται).

4:14b Well, in the same way, God will gather together with [Jesus] those who have died in him (οὕτως καὶ ὁ θεὸς τοὺς κοιμηθέντας διὰ τοῦ Ἰησοῦ ἄξει σὺν αὐτῷ). Paul argues that belief in Jesus’ resurrection leads to a corollary, namely, the resurrection of the saints. This is translated “well, in the same way” (οὕτως καί), so that it doesn’t seem as if “we believe” in 4:14a is the cause of final resurrection. Rather, this is an example of evidence–inference, where “the speaker infers something (the apodosis) from some evidence.”8 Jesus rose (so we believe) from the dead; in the same way God will resurrect the saints.

Paul delays the explicit promise that God will resurrect the dead believers. In this verse, “[God will] gather together” (ἄξει, from ἄγω) the dead. In the gospel tradition, the parousia involves the gathering of people from around the world: “And he will send his angels with a loud trumpet call, and they will gather [from a compound of ἄγω, ἐπισυνάγω] his elect from the four winds, from one end of the heavens to the other” (Matt 24:31).9 Similar language appears in 2 Thess 2:1, where the saints are “gathered together” unto Christ (the cognate form ἐπισυναγωγή). Likewise, the ancient text Did. 10.5 instructs the church to pray that God will “gather [συνάγω] [the church] … from the four winds into your kingdom.” Paul will show in 4:16 that this gathering is accomplished through resurrection, not through a summoning together of the spirits of the disembodied dead.

For the expression “those who have died” (from κοιμάω), see 4:13. “In” (διά) is not the language Paul typically uses to speak of being in Christ; nevertheless, that seems to be his sense here, giving a parallel to “the dead in Christ” (οἱ νεκροὶ ἐν Χριστῷ) at the end of 4:16. An alternative might be that these saints died because of their association with Jesus, that is, that they were martyrs; or perhaps the phrase “with Jesus” (διὰ τοῦ Ἰησοῦ) is connected not with the participle but with the verb “will gather”: “through Jesus, God will bring with him those who have fallen asleep” (ESV). But this latter seems to be an awkward rendering of διά, which seems to connect better with the words that immediately precede it, “have died.”

Paul is at odds with some Christian thinking of our day; our eschatology has been affected over the centuries by foreign influences. In particular, we have become accustomed to the phrase “immortal soul,” that the soul lives in a mortal body but does not really require it. The roots of that idea lie in Greek philosophy: for example, Plato has Socrates say that for the philosopher, one’s final purification

consists in separating the soul as much as possible from the body, and accustoming it to withdraw from all contact with the body and concentrate itself by itself; and to have its dwelling, so far as it can, both now and in the future, alone by itself, freed from the shackles of the body…. Will [the philosopher] be grieved at dying? Will he not be glad to make that journey?10

Thus the philosopher realizes that death is not a frightening loss, since the soul is better off without the body. Paul for his part sees that death is indeed a cause for sorrow, but grief that is transformed by the Christian’s hope for the resurrection.

In the Bible, immortality is an attribute of God, meaning that he is not susceptible to death (1 Tim 1:17). This is nowhere said to be a characteristic of the human soul, even when it teaches that the soul or spirit remains conscious after death.11 Immortality (Rom 2:7; 1 Cor 15:53–54) or “eternal life” (Rom 6:23) in Pauline terms is always associated with the eschatological resurrection: God in the future will give eternal life, transforming the human body into an undying form. This meant that Paul had his work cut out for him as he taught about life and death “to an audience that denied an afterlife or held that immortality was theirs by natural endowment” or held to a hereafter of shadows.12

4:15a For we say this to you by an oracle from the Lord (Τοῦτο γὰρ ὑμῖν λέγομεν ἐν λόγῳ κυρίου). Paul now gives the cause for his assertion in 4:14 by revealing the source of his doctrine: a direct revelation from the Lord Jesus. He uses language that is reminiscent of the LXX. “Lord” (κυρίου) is a subjective genitive, indicating that “the Lord spoke.” The LXX typically uses “word [ῥῆμα] of the Lord” to refer to a word of prophecy.13 Its synonym (i.e., λόγος) also occurs in the LXX and functions interchangeably with ῥῆμα.14 The phrase in Thessalonians, “by an oracle from the Lord,” is based on an instrumental usage of “by” (ἐν). A parallel may be found in 1 Kgs (3 Kgdms LXX) 13:18, where a prophet falsely claims that an angel had spoken to him “by a word of the Lord” (ἐν ῥήματι κυρίου).

The question now arises whether Paul might be referring to a saying of Jesus from his earthly ministry (as he does about marriage in 1 Cor 7:10; cf. also 11:23).15 In a variation of that position, Seyoon Kim has argued forcefully that Paul has inferred 4:15–16 from the Jesus tradition in general, but not from a specific saying.16 The difficulty is that there is no known Jesus tradition that resembles the material in 1 Thessalonians. In that case, it would have to be an agraphon, that is, an oral tradition not included in the gospels.17 This hypothesis must remain a speculation. The better interpretation is that it is a word given to a Christian prophet such as Silas (he was a prophet, see Acts 15:32) or even to Paul himself.18 It would fall into the category of revelation that Jesus promised in John 14:26, that the Spirit would “teach [them] all things.” Paul is known to pass along new truth given directly by God: coincidentally he would disclose a similar “mystery” in 1 Cor 15:51, the parallel passage parallel to 1 Thess 4:13–18.19 He will soon teach the Thessalonians to hold prophecy in its proper honor (5:20) but also to beware of false messages (the deceiving “spirit” in 2 Thess 2:2).

4:15b That we who still live and remain here until the Lord’s coming (ὅτι ἡμεῖς οἱ ζῶντες οἱ περιλειπόμενοι εἰς τὴν παρουσίαν τοῦ κυρίου). The new datum is not the fact that Jesus will return, but that at the parousia dead believers will ascend first, to be followed by living Christians. Paul relates the content of this revelation in an “indirect discourse,” that is, “the ὅτι clause contains reported speech or thought.”20

“We who still live and remain” (ἡμεῖς οἱ ζῶντες οἱ περιλειπόμενοι, see also 4:17) has two present tense participles. But the present tense does not necessarily imply that the actions take place in present time, as if Paul were speaking of those now alive and now remaining; substantival present participles do not necessarily indicate an action that takes place at the time of the statement.21 Our translation restates what the Greek says, no more and no less.

Scholars have tended to overinterpret Paul’s use of the first person plural, that is, “we who live and remain.” There is sufficient evidence elsewhere that Paul did not expect necessarily to live until the parousia or that, by implication, the parousia was near at hand.22 First, the apostle faced death daily; even if a man of his age might expect to enjoy another twenty years of life, his lifestyle was by no means normal. With his constant encounters with near-fatal beatings, exposure, imprisonments in unhealthy conditions, malnutrition, bandits, shipwreck, and other threats to life (cf. 2 Cor 11:23–27), one should wonder how such a man could expect to see any future event, let alone Christ’s return.

Second, Paul’s intention here is to speak about believers who are living at the time of the parousia. He uses “we” for the simple reason that he was then alive and speaks of what living Christians should expect were the parousia immediate. He goes further and includes the Thessalonians in the “we,” even though some of them at that moment are facing death. Only the living write and read letters, and so the words are geared to those “who still live.”23

Third, in other contexts, where appropriate, Paul could speak as if he were identifying with believers who were already dead: “We know that the one who raised the Lord Jesus from the dead will also raise us [the dead] with Jesus and present us [the dead] with you [the living Corinthians] to himself” (2 Cor 4:14; see also 1 Cor 6:14). Paul is offering no prediction in 1 Thessalonians as to whether or not the parousia would take place during his lifetime (see also comments on 5:1–2; 2 Thess 2:1–2).

4:15c Will in no way go ahead of those who have died (οὐ μὴ φθάσωμεν τοὺς κοιμηθέντας). Paul now delivers the content of the word from the Lord: believers who manage to survive until the parousia will certainly not be the first to be summoned to go out and meet Christ. He uses “in no way” (οὐ μή), the Greek double negative making it especially emphatic: living Christians “will in no way go ahead” (φθάσωμεν). This verb often has the more general sense of “come, arrive” (as in 2:16; Matt 12:28); here alone in the NT it means “go ahead of” or “precede.”24 The parousia is not just the coming of Christ from heaven. There is also movement on the part of Christians, the dead first and then the living. The rendezvous will take place “in the air” (1 Thess 4:17). For “died” (κοιμάω as metaphor for death) see 4:13.

4:16a-c Because the Lord himself, with the commanding shout of the archangel’s voice and with the [sound of the] trumpet of God (ὅτι αὐτὸς ὁ κύριος ἐν κελεύσματι, ἐν φωνῇ ἀρχαγγέλου καὶ ἐν σάλπιγγι θεοῦ). The apostle has just shown that God will “gather together” the dead Christians; now he demonstrates what the parousia will be like and how the dead will be resurrected and go ahead of the living believers.

The word “because” (ὅτι) here is causal; that is, Paul shows on what grounds he has made the claim in v. 15. The phrase “the Lord himself” has its roots in the Scriptures (e.g., Isa 7:14 LXX; cf. also T. Sim. 6.5 [ed. Charlesworth]—“the Lord God shall appear on earth, and Himself save men”). For Paul, an integral part of the end of the age is that God’s people will be gathered to the Lord they love; see also 4:17, “so we will always be with the Lord.” The parousia will mark a new phase in the Christians’ relationship with their Savior. It is this personal relationship that contrasts with the pantheistic eschatology of Sallustius in the fourth century AD: “Souls that have lived in accordance with virtue have as the crown of their happiness that freed from the unreasonable element and purified from all body they are in union with the gods and share with them the government of the whole universe”; that is, there is no resurrection and no personal loving communion with God.25

The Lord comes with blasts of sound, introduced by “with” (ἐν). Are there three (i.e., shout, voice of the archangel, trumpet of God) or two (i.e., shout made with the voice of the archangel, trumpet)? Most versions leave the question unanswered. The NJB, however, makes an explicit identification between the shout and the archangel: “at the signal given by the voice of the Archangel.” This gives the best sense, since otherwise there would be a shout and then some other noise, voiced by the angel. “With the commanding shout” (ἐν κελεύσματι) is an authoritative command, not simply a loud noise.

There is a parallel in Joel 3:16 that likewise refers to the eschatological epiphany: “The Lord will roar from Zion and thunder from Jerusalem; the earth and the heavens will tremble.” Another parallel is found in Philo, whose death occurred around the time Paul wrote 1 Thessalonians. Philo is speaking of God’s power to bring people to repentance, no matter where they have strayed: “God, by one single word of command [ἑνὶ κελεύσματι], could easily collect together men living on the very confines of the earth, bringing them from the extremities of the world to any place which he may choose, so also the merciful Saviour can bring back the soul after its long wandering.”26

Morris comments that Paul has no particular archangel in view. Yet he reads too much into the absence of the definite article, thinking it must therefore mean “an archangel.”27 The Greek article does not function as does the English, and Paul could easily be speaking of “the” or “an.” Only in this passage and Jude 9 do we find this compound noun “archangel” (i.e., lead angel). Michael is the one named in the Jude passage. His name is also found in the OT, in Dan 10:13, where he is an angelic “prince” (ἄρχων). Michael and his angels fight the dragon and his forces in Rev 12:7.

Within the elaborate models of postbiblical Judaism, Michael emerges as the special defender of Israel.28 According to 3 (Greek) Baruch 11.2, it is Michael who holds the keys to the kingdom of heaven. While Paul does not name the angel here, it seems likely that he has Michael in mind. He is in some way associated with the resurrection of the saints in Dan 12:1, and it is even possible that Michael is the “restrainer” of 2 Thess 2:6–7 (see comments on that passage). Nevertheless, Paul’s focus is not on the layer upon layer of angelical hierarchy that one finds in the apocalyptic tradition. As this verse stresses at the beginning, the central figure is “the Lord himself,” and all other beings are subordinated to him.

The “trumpet of God” at the resurrection is clearly a parallel to 1 Cor 15:52: “… at the last trumpet. For the trumpet will sound, the dead will be raised imperishable.” The trumpet too finds its background in the OT29 and in the Jesus tradition: “And he will send his angels with a loud trumpet call” (Matt 24:31). What Paul does not include here in 1 Thess 4:16 is the plurality of “holy angels” from 3:13, nor does he explain the role of the angels in gathering the elect, as stated in the Olivet Discourse.30

Oddly, some imagine that Paul’s words here are derived from Jewish apocalyptic language. This cannot be so, for one searches in vain in known Jewish apocalypses to find any statement of a descending Messiah that resembles 4:16. Rather, Paul has woven together elements from the OT descriptions of “theophany” (the glorious appearing of the Lord) and the Jesus tradition, along with a fresh revelation.

4:16d Will come down from heaven (καταβήσεται ἀπ’ οὐρανοῦ). Paul now moves to the central event of the parousia: Jesus will descend from heaven; that is, he will come down to the earth, and the saints will meet him in the air. The same vocabulary is found in John 6:38, but there Jesus speaks of his mission on earth: “I have come down from heaven [καταβέβηκα ἀπὸ τοῦ οὐρανοῦ] not to do my will but to do the will of him who sent me.” More closely related conceptually to 1 Thess 4:16 is the descent of angels from heaven (Rev 10:1; 18:1; 20:1); the ascent of Jesus to heaven with the promise that he will “return” (Acts 1:11); and Paul’s later statement that “we eagerly wait a Savior from [heaven], the Lord Jesus Christ” (Phil 3:20). The topography of 1 Thess 4:16 runs from the surface of the earth, to the air, and then to heaven. While theologians across two millennia have proposed that heaven is not really vertically “up from” the surface of the planet, the New Testament writers were comfortable with that language as one way to describe the relative positions of heaven and earth.

4:16e And the dead in Christ will first be resurrected (καὶ οἱ νεκροὶ ἐν Χριστῷ ἀναστήσονται πρῶτον). Here is the solution to the Thessalonians’ grief: as Christ was resurrected, so now will those who died in him be resurrected at his parousia. This resurrection is the first part of the gathering of the saints. Paul does not develop, as he will in 1 Cor 15:35–49, the nature of the resurrection body.

We render the verb “will be resurrected” (the future passive, ἀναστήσονται) rather than the traditional “will rise,” which might be confused with the rising “in the air” (4:17). Many have noted the odd fact that nowhere does Paul write that the wicked will be resurrected. One has to draw that from Acts 24:15, where he states before Felix, “there will be a resurrection of both the righteous and the wicked.” This omission of the resurrection of the damned in 1 Thess 4 seems to be due to his interest in “the dead in Christ,” including the fatalities that some believers in Thessalonica have already suffered. The same seems true of 1 Cor 15:52: the dead believers will be raised incorruptible, and we [living Christians] will also be changed. In Acts 24, by contrast, Paul is speaking to non-Christians and gives out the truth that would be applicable to them as well. Paul uses “first” in 4:16 (πρῶτον) to denote a chronological order, following it up with “next” (ἔπειτα) in 4:17.

The author of Hebrews later reminded his readers that the eschatological “resurrection of the dead” was among the “first lessons of the Christian message” (Heb 6:1–2 GNB). How then had the Thessalonians missed out on this basic tenet? It is possible that there were countercurrents that pushed against the resurrection doctrine. In Macedonia, it would have been all but impossible to encounter the resurrection teaching in any venue apart from the synagogue and the newly planted church. Everything about the Greek worldview, be it in popular religion or erudite philosophy, resisted what would have seemed like the reviving of rotting cadavers. This, rather than some hypothetical Gnostic tendency, is the best explanation of why some in Corinth rejected the resurrection. Like the Sadducees and the Hellenists, they jibed, “How are the dead raised? With what kind of body will they come?” (1 Cor 15:35). Paul reminds the Corinthians of certain points of Christology and the doctrine of creation to show that it is not outlandish.

We have little idea of why some in Ephesus would say that the resurrection had already taken place (2 Tim 2:18), although in that case, they may have been anticipating what would blossom in the second century: Gnostics would reject the doctrine wholesale, along with the incarnation, death, and resurrection of Jesus.31 Hence the Fathers as early as the second century fought hard against a hyperspiritualized Christianity that rejected God’s continued interest in the material world.32 The best explanation for the Thessalonians is that they heard that truth, but then had trouble grasping it when it was no longer a hypothetical question but a crisis over what would happen to the fallen ones in their small congregations. Nevertheless, it is unlikely that the question of “why” can be answered definitively unless further information be forthcoming. See the Introduction, “Eschatology in Thessalonica.”

4:17a-d Next, we who still live and remain will be taken up together with [those who were dead] in the clouds to welcome the Lord in the air (ἔπειτα ἡμεῖς οἱ ζῶντες οἱ περιλειπόμενοι ἅμα σὺν αὐτοῖς ἁρπαγησόμεθα ἐν νεφέλαις εἰς ἀπάντησιν τοῦ κυρίου εἰς ἀέρα). The people of Christ will go forth to meet him at his parousia in two stages: first, the resurrected dead; “next,” the living believers. Paul now speaks of this second group. He repeats the phrase from 4:15, “we who still live and remain” as a rubric for living Christians. They will be “taken up together with those who were dead … in the air.” Paul is still speaking in terms of vertical movement: Christ descends from heaven, the dead arise, and living Christians are snatched upward with them into the “clouds” and into the “air.”

Paul uses the future passive of the verb “taken” (from ἁρπάζω). The Latin Vulgate translates the verb as rapiemur, a form of rapio; from this is derived the English word “rapture.” God “takes” Paul from earth to the third heaven in 2 Cor 12:2, 4. But in itself the Greek verb does not convey vertical movement, that is, of being “caught up”; it could refer to “being taken from one place to another.” For example, in Acts 8:39 the Spirit snatches (form of ἁρπάζω) Philip from the Gaza Road to Azotus. Some have concluded that the rapture must mean the transportation of the saints from earth to another location, heaven, to wait out the tribulation. This is not indicated: rather, when the believers are caught up from one place to another, it is from earth to “the air.” The verb “taken up” is a “divine passive,” since God is the one who gathers the saints (see also 4:14).33

First Thessalonians 4:17 is the only explicit New Testament reference to the saints being raptured “upward” at the parousia;34 other terms, such as “gather,” while easily accommodating the idea of an ascent, do not demand a vertical movement. The reference to Enoch’s translation in Gen 5:24 likewise does not say that Enoch went “up,” but simply that God “took” or (in the LXX) “transferred” him.35

“Cloud” has a variety of uses in eschatological passages. It may allude to the innumerable heavenly armies (cf. Jude 14; 1 Thess 3:13); to literal clouds, betokening the ascension into the upper air; to the cloud of glory on which sits the Son of Man; or to a heavenly cloud that transports Christ or his saints (Matt 24:30). The closest parallel to 1 Thess 4:17 is Rev 11:11–12, where the slain witnesses are resurrected and ascend into heaven in a cloud. So, “cloud” as heavenly vehicle is the preferred understanding, as is shown by Acts 1:9, 11: “After [Jesus] said this, he was taken up before their very eyes, and a cloud hid him from their sight…. ‘This same Jesus, who has been taken up from you into heaven, will come in the same way as you have seen him go into heaven.’ ” “In the air” is simply the atmosphere.

“Together” (ἅμα) is used in the parable of the tares in Matt 13:29, where the master forbids the servants from uprooting the weeds and hence damaging the grain. Here in 1 Thess 4:17 it signifies the reuniting of the people of Christ in the eschatological moment; we all join together, and it is the ascension of the living believers that is the second step that will complete the assembling of God’s people.

Paul does not divulge here the truth of 1 Cor 15:51, the “mystery” that “we will not all sleep [die], but we will all be changed”; that is, the living believers too must undergo a transformation. Paul calls it a “mystery,” perhaps another new revelation. Since he doesn’t mention it here, and since it seems to be new information in 1 Cor 15, it is unlikely that the doctrine of the “transformed living” was a part of the apostolic preaching at the time of 1 Thessalonians.

In our translation, “to welcome” follows the lead of most English versions by making a verb of the prepositional phrase “for a meeting” (εἰς ἀπάντησιν). The basic translation “to meet” or “to welcome” is technically correct, but what happens after the Christians meet the Lord in the air? Where do they go? Paul does not say, neither here or in 1 Cor 15:52. In some systems of eschatology, Christ comes close to the earth, to the atmosphere, to receive the saints and then takes them back with him to heaven.36 Another interpretation is that Christ comes back, the saints go forth to meet him, and then they accompany him as he continues on his way to earth.

In the absence of explicit details, is there some implicit indication of what is to follow? Apparently so: the Greek “meeting” (ἀπάντησις as here, and its cognate ὑπάντησις)37 is not simply going to encounter someone, but rather “the action of going out to meet an arrival, especially as a mark of honour.”38 When a dignitary came to visit a city in those days, the inhabitants would pay him tribute by going out of the city to meet him at the proper time. They would then accompany him back to the city he was planning to enter. This is what happened in John 12:13, where the crowd on Palm Sunday came out of Jerusalem to meet Jesus (ὑπάντησις) and accompany him back in to the city. Moreover, the Olivet Discourse contains the metaphor of a ruler coming to the city, which he then enters; “when you see all these things: know that he is near, right at the gates” (Matt 24:33 NJB).39

What makes Paul’s language unusual is the spatial reorientation of the “meeting.” He turns the horizontal action of the dignitary’s approach, reception, and entrance into a gated city into a vertical action: when Christ comes, he “will come down” to his domain, and his subjects ascend “in the clouds … in the air,” as befits his deserved honor.40 Based on this conventional usage of “meeting” (ἀπάντησις), it may be concluded with a relatively high degree of certainty that Paul envisions Jesus coming in the air; resurrected believers and then living ones will ascend to honor him, and they will then accompany him back to the earth.41 This lies close to the thought of 2 Thess 1:10: “when he comes to be glorified among his saints and to be worshiped among all who have believed.” Paul’s language, while taken from earlier tradition, would have sounded political to residents of the empire: Christ, not Caesar, is the true king, the one whom Christians should receive as their sovereign; Christ’s peace, not Caesar’s “peace and security” (1 Thess 5:3), is the true reality.42

4:17e And so we will always be with the Lord (καὶ οὕτως πάντοτε σὺν κυρίῳ ἐσόμεθα). In John’s gospel, Jesus promises, “I will come back and take you to be with me that you also may be where I am” (John 14:3). For his part, Paul shows that Jesus will come, not just to take individuals to him, but to gather together and be with his people as a body. The apostle uses “and so” (καὶ οὕτως) to demonstrate that the resurrection and rapture of the saints is the manner in which they are united forever with him. Paul leaves open what is the exact meaning of being “always … with the Lord.” This state is beyond human description, even for an apostle who is disclosing a prophetic word (4:15). But he has made the point the Thessalonians needed to hear: we, that is, the living and the dead, will be together with Jesus, and living Christians may be confident that they will see their deceased friends in his presence.

4:18 So then, encourage one another with these words (Ὥστε παρακαλεῖτε ἀλλήλους ἐν τοῖς λόγοις τούτοις). Paul concludes with “so then” (ὥστε) in order to show the Thessalonians what to do with this information. In Gnosticism, information about the true nature of resurrection would have been part of a higher plane knowledge, not able to be absorbed by rank-and-file Christians. But Paul does not make this information private and individualistic but corporate; if properly grasped, it will lead them to “encourage one another” (παρακαλεῖτε ἀλλήλους); see also 5:11: “so then, encourage and build up one another.” “With these words” are not simply words of emotional support, but words of revelation that are by nature encouraging, on which they should base their speech to other believers and help them to throw away their un-Christian grief.

Theology in Application

With the doctrine of the resurrection, Gentile converts were to accept and put into daily practice a radically new paradigm.

Theology in Thessalonica

The Jewish colony in Thessalonica differed from its religious context in many respects. Most Jews believed that history was moving toward a final conclusion (a telic view of history), an end that was in God’s hands. In addition, most Jews believed in the resurrection of the body as the redemption of God’s physical creation (cf. Dan 12:2–3). In the story of Lazarus, Martha is quoted as giving a simple but definite confession: “I know he will rise again in the resurrection at the last day” (John 11:24). An inscription from Rome (second or third century AD) over the grave of a twenty-year-old Jewish wife reflects that view of the resurrection:

Here lies Regina…. She will live again, return to the light again, for she can hope that she will rise to the life promised, as is our true faith, to the worthy and to the pious, in that she has deserved to possess an abode in the hallowed land…. Your hope of the future is assured. In this your sorrowing husband seeks his comfort.43

A few of the new Christians in Thessalonica came from that synagogue background, but most did not.

The Greek view of death varied widely.44 The followers of Plato, for example, believed in the reincarnation, or transmigration, of the soul: the soul goes into a new body (perhaps human, perhaps animal) and recalls something of the experience and wisdom of past lives. Others Greeks believed that death was the end of existence. For example, the Epicureans thought that human consciousness dissolved with the body:

Accustom yourself to believe that death is nothing to us, for good and evil imply awareness, and death is the privation of all awareness; therefore a right understanding that death is nothing to us makes the mortality of life enjoyable, not by adding to life an unlimited time, but by taking away the yearning after immortality.45

The Stoics believed in the survival of death, but not as personal beings. According to Marcus Aurelius:

The souls which are removed into the air after subsisting for some time are transmuted and diffused, and assume a fiery nature by being received into the seminal intelligence of the universe, and in this way make room for the fresh souls which come to dwell there. And this is the answer which a man might give on the hypothesis of souls continuing to exist.46

These ideas, along with the lore of the mystery religions, were always minority views, held by people with some taste for philosophy or for arcane religion. For his part, Paul was writing to Greeks who had “no hope” apart from Christ, that is, people who held to the majority opinion that the soul would travel to a gloomy underworld. Even if they might encounter their dead friends in the life beyond, it would be in a realm of shadows, known for its drab hopelessness.47 Tombstones have been recovered from all over the empire, and they reveal something of the popular mindset. An inscription from Thessalonica itself shows the misery of death; the widower built a tomb “that later he would have a place to rest together with his dear wife, when he looks upon the end of life that has been spun out for him by the indissoluble threads of the Fates.”48

How does one carry on when the future looks so baleful? Some Greeks would simply cry and wail against the destiny that awaits all people.49 Others urged acquiescence to one’s inevitable fate. Paul’s contemporary Seneca—whose brother, Gallio, crossed paths with Paul as proconsul of Corinth—took a typical philosophical approach. Grief, like all passions, should be moderated, and the wise man should control himself. If someone should tell Seneca that “ ‘One should be allowed a certain amount of grieving, and a certain amount of fear,’ I reply that the ‘certain amount’ can be too long-drawn-out, and that it will refuse to stop short when [eventually] you so desire.”50

Paul went directly against the grain, preaching the resurrection of Jesus and also the future resurrection of all humanity: “I have the same hope in God these [Pharisees] themselves have, that there will be a resurrection of both the righteous and the wicked” (Acts 24:15).51

Since the Thessalonians seem to have missed out on the implications of the resurrection doctrine, Paul writes to fill in this gap in their understanding. They should not grieve as others do. Yet Christianity is not Stoicism. When Christians lose friends from church, who are, at the deepest level of truth, family members, their grief should be shaped and moderated by the resurrection hope that lies at the foundation of the gospel.

Biblical Theology

Paul is the most prominent spokesman in the Scriptures for the doctrine that death is the result of human sin. While this is implicit in Gen 2:17; 3:19, and in other places, neither the authors of the OT, the literature of Second Temple Judaism, nor the NT authors give it the strong development found in Rom 5:12 and its context. In addition, Paul makes the corollary doctrine of the resurrection an integral component of divine salvation: “just as Christ was raised from the dead through the glory of the Father, we too may live a new life” (Rom 6:4b; see also 8:11).

The resurrection is not some isolated doctrine. It is part and parcel of the truth that God is the “living God, who made the heavens and the earth and the sea and everything in them” (Acts 14:15). Within this worldview, God has the authority to redeem life out of death.52 If God can create life from nonlife, he is ready to create life even from the bodies of the dead.

To the surprise of many, in no Scripture does one find the Greek phrase “the immortality of the soul.” To be mortal simply means to be capable of death. Human beings since the sin of Adam have been inherently mortal, that is, subject to bodily death and decay. No mortal may inherit the eschatological kingdom (1 Cor 15:50), and therefore the dead must be resurrected and the living transformed into immortality (1 Cor 15:51–53). As a second-century preacher would come to express it: “So great is the life and immortality which this flesh is able to receive, if the Holy Spirit is closely joined with it, that no one is able to proclaim or to tell ‘what things the Lord has prepared’ for his chosen ones” (2 Clem. 14.5).53

Some contemporary views of the afterlife suffer from reductionism. According to Rudolf Bultmann, no God will break into history to save us. There is no coming kingdom, parousia, Satan, demons, or three-storied universe consisting of heaven, earth, and hell:

This conception of the world we call mythological because it is different from the conception of the world which has been formed and developed by science…. In this modern conception of the world the cause-and-effect nexus is fundamental … modern science does not believe that the course of nature can be interrupted or, so to speak, perforated, by supernatural powers.54

Bultmann concluded that the apocalyptic message calls modern hearers outside themselves to an existentialist understanding of their reality. But in fact Bultmann approximated the approach of many philosophers of Paul’s day, who understood the old pagan myths as mere metaphors. Paul for his part could not accept that sort of ahistorical hermeneutic, since for him the literal history of Jesus was the foundation of the gospel. In the case of the believer’s resurrection, no mere feeling of hopefulness provided the foundation for Paul’s confidence that God would raise people from the dead just as he had Jesus.

Message of This Passage for the Church Today

Paul wrote this letter as a Christian pastor. He knew the value of theology for altering human psychology and insisted on the Thessalonians encouraging one another with good eschatology (4:18). They could now appreciate yet another facet of Christ’s gift of salvation, the physical and the eschatological level.

It is regrettable that so many of today’s Christians read volume after volume of “pop eschatology” and yet seem at a loss to better understand their future hope. For example, I just browsed through a painfully detailed study that “proved” that Prince Charles of England is the antichrist, and that no other possible candidate is possible. We should include here the growing set of people who supposedly have died and then returned to write up what they saw in heaven. But where is the flood of popular interest in the truly fundamental themes of the end times: judgment, vindication, resurrection, kingdom, and others—not to mention their traveling companions, joy, hope, faith, and mutual encouragement? Where are the teachers who will work through the details of eschatology so as to draw the larger conclusions about the divine nature? Eschatology, like any other part of our belief system, must be doxological; that is, it must lead to glorifying God.

Then too, many Christians neglect the resurrection doctrine and place too much weight on the doctrine of dying and going to heaven. Two books that we commend as a corrective are by Rebecca Price Janney, Who Goes There? A Cultural History of Heaven and Hell (Chicago: Moody Press, 2009); and N. T. Wright, Surprised by Hope: Rethinking Heaven, the Resurrection, and the Mission of the Church (New York: HarperOne, 2008). There is also a fine section by Beverly Gaventa in her Thessalonians commentary on “Preaching and Teaching Eschatology.”55

Let us explore how a proper emphasis on the resurrection might affect our proclamation.

The Christian funeral. “He is no longer suffering; he is in heaven, where we will join him; God will comfort the bereaved with his loving presence.” Such is the form into which the funeral oration has evolved. The difficulty with it is not that it is mistaken, but that it is ill-proportioned. Paul would probably have preached a funeral sermon along the lines of: “He testified to Christ in his life, despite opposition, right to the end; he is in the presence of Christ; he will be resurrected when Christ returns, where we will see him in the presence of our Lord; God comforts us by reminding us that he has destroyed death in Jesus.”

Evangelism. When Paul proclaimed the resurrection of Jesus at Athens, he was mocked (Acts 17:31–32). His modern counterparts might be tempted to skip over the eschatological resurrection of the saints as a necessary corollary to the Easter faith. But what is demanded of us today is not avoidance but an insightful biblical and cultural interpretation of the resurrection message to each generation. One route is to take advantage of our contemporaries’ obsession with their health. The media are saturated with medical reports, health advice, and new diets. Western culture is also obsessed with staying young, to the point of having multiple elective surgeries. People feel youth—and thus, life—slipping away, and there is no brake against it. With extended life spans, people are living long enough to experience more diseases, such as arthritis, Alzheimer’s, cancer.

The gospel does not promise some final release from the physical body but its perfect transformation. Take the woman with arthritic fingers: in Christ, she can look forward to, not reincarnation (as an animal, or if she is lucky, another human being who in turn is doomed to growing old again), nor the laying aside of the body, to live as a disembodied spirit, nor being extinguished. Rather, she can experience the transformation of that very hand so that the joints work precisely as her Maker intended, and in ways beyond our current reckonings.

By the same logic, those who do not know God cannot flee him through extinction or reincarnation or a flight into the cosmos as a phantom. No, such people will stand resurrected to give account of what they have done in the body (2 Cor 5:10), and will then exist forever in bodies that can experience torment and the pain of absence from God (Rev 20:13). If the resurrection is the bedrock the Christian’s expectation, it is also the terror of those without hope.