CHAPTER 3

Visualizing war victims

Rädda Barnen’s humanitarian reporting in the interwar years

Dwarfed by rickets and bone softening, ruined, deformed creatures with unnaturally big heads, pale cheeks, the facial expression that of old people, the skin shrunk and dry due to lack of fat, their tummies swollen like drums, underdeveloped legs as thin as sticks compared to the body, knees clenched, unable to walk, and usually to talk, too. This is how they look, the children of the twentieth century in the suffering Berlin and the starving Vienna.1

The twentieth century should have been a century of hope and progress, ‘the century of the child’ as the Swedish author Ellen Key had put it in her famous work first published in 1900.2 But as Alice Trolle wrote in the Swedish daily newspaper Svenska Dagbladet as one of Rädda Barnen’s (RB; Swedish Save the Children) representatives in Austria, by the end of the First World War the surviving children of the new era looked completely different: suffering, starving, ruined, deformed. What to make of the terrible sight of such prospects? What did the emaciated war child’s body signify to the RB, and how did the organization direct the eyes of the Swedish audience to the suffering? As Trudi Tate reminds us, the anxiety of bearing witness to war ‘is expressed most powerfully through the sight of the suffering human body, the place in which history and fantasy meet’.3 This chapter investigates practices of seeing and sensing total war in the humanitarian reporting of the RB’s media campaigns in the early twenties, focusing on the organization’s strategic emotional uses and sensory representations of the war child’s body. I will examine how and why the RB invested in a certain moral rhetoric of seeing and feeling suffering in order to ameliorate it, showing that a visual–visualizing discourse was key to its interwar humanitarian imagery. To behold the smallest and most vulnerable remains of war was to experience their pain, and to realize that they had the right to be saved.

A humanitarian awakening

When the RB was founded in November 1919, only the second counterpart to the pioneering children’s relief and rights organization, the British Save the Children Fund (SCF), it was part of the ‘great humanitarian awakening’ in the wake of the mass death of the First World War.4 Branden Little has suggested that the war’s ‘dynamic of destruction’ was countered by a ‘dynamic of salvation’, igniting an explosion of humanitarian activity by old and new actors alike.5 In the expanding field of the history of human rights and humanitarianism, the legacy of the First World War—long eclipsed by the Second—has attracted increasing attention from scholars over the last decade.6 However, humanitarians’ sensory experiences and emotions in war have yet to be investigated, not least from a media history perspective, and it is there this chapter makes a contribution.7 It does not help that the field has been heavily biased towards American and British humanitarianism, with the history of Save the Children largely the history of the SCF.8 In contrast, in this chapter I present new archival findings from the lesser-known but still highly influential Swedish organization, focusing on its media campaigns in the early twenties.9 With the ‘neutral periphery´ viewpoint of Europe, I offer a different perspective than the standard one on how humanitarians mediated war and suffering in the interwar years. During the conflict and its aftermath, neutral Sweden saw several humanitarian enterprises, including relief action for Belgium and a huge exchange of invalid POWs administered by the Swedish Red Cross.10 In the national imagination and in the eyes of the international community, Sweden was increasingly constructed in exceptionalist terms as a peaceful ‘humanitarian great power’ and a progressive ‘champion of the child’.11 Both images permeated the humanitarian imagery of the RB, where Sweden saving children and the peace were discursively linked.

During the organization’s first six years, the period covered here, the RB headed an impressive international humanitarian effort, helping mostly Central European children and their families with food, medicine, care, clothes, fuel, work, and housing. It managed local orphanages, kindergartens, canteens, and sanatoriums, and offered children temporary (and sometimes permanent) homes with Swedish families.12 Mediations of the suffering child played a crucial role in this effort, engaging the neutrals in what Stefan Ludwig Hoffmann calls ‘a compassionate gaze at Europeans’ and at a continent in ruins.13 In the interwar years, the daily and weekly press, films, novels, and women’s magazines were key in constructing starvation in distant Central Europe as a ‘disaster’, making it a media event for the Swedish public.14 Exposing the body of the war child brought a different kind of ‘war news’, and fostered new ways of seeing and feeling suffering. By highlighting and sponsoring the RB’s humanitarian work, the press also offered readers a way to help solving the terrible situation. It was news reporting and promotion of the RB at the same time. In both cases, the RB cause benefitted from the more socially engaged and active journalism established during the war years, when Swedish newspapers had become increasingly involved in fund-raising activities for the needy, addressing the readers as both donors and benefactors, and alleviating the pressing situation by proffering a helping hand.15 The RB was part of this reciprocal development, where the daily press became more humanitarian and the reporters acted more as humanitarians; and humanitarianism in turn became more oriented towards the narrative techniques and visual strategies of the so-called ‘new journalism’, resting on ‘the epistemological authority of the “eyewitness account”’ and investigative reports, exposés, drama, and human interest stories.16 As actors and spectators, participants and witnesses all at the same time, humanitarian reporters and reporting humanitarians together made common cause over the image of the emaciated toddler, one of the most powerful icons for aid in the postwar years—‘a projection screen for public appeals to end and relieve the suffering of the crushed nations’.17

The RB originated in a press appeal, and the organization was convinced of the importance of using the media to promote its cause, so it prioritized this part of its strategic work, despite a stretched budget. The RB had a special ‘press and propaganda section’ with a full-time press officer and a member’s paper (Rädda Barnen). They had frequent access to the daily and weekly press, especially women’s or family magazines such as Idun, Husmodern, and Veckojournalen. Articles and reports by the RB representatives—many of whom were also well-established journalists, writers, and opinion makers such as Anna Lenah Elgström, Anna Lindhagen, Gerda Marcus, Marika Stiernstedt, and Elin Wägner—were published in Stockholm’s daily papers along with the RB appeals and advertisements, and this material was frequently reprinted (sometimes under new headlines) in the local press a few days later. The papers regularly published interviews with the leading RB figures and reports from its meetings and congresses, and reproduced its public lectures as well as its appeals to the Swedish public. Many newsrooms administered donations to the organization from their readers and made big donations themselves. The newspapers sponsored special fundraising events such as ‘Linen Sunday’ in 1920, promoting them for weeks at a time.18 The intensive press coverage of the RB activities testifies to the war children becoming a national preoccupation in Sweden, and how this early form of human rights reporting and activist journalism made distant European suffering into breaking news on Swedish front pages.

The morality of sight

Ever since the first wave of humanitarianism in the late eighteenth century, sympathy has been regarded as spectatorial in nature, and a sentiment prompted mainly by sight. The humanitarian narrative appealed to the reader’s senses—especially ‘the morality of sight’—by making the eyewitness into a compassionate donor and activist.19 The moral rhetoric of early twentieth century humanitarianism had an instructive aspect, for it encouraged particular ways of seeing and feeling about suffering, and taught the public how to experience and act on those feelings.20 Following Heide Fehrenbach, it was a kind of moral training of vision and emotion.21 Thomas W. Laqueur holds that humanitarian narratives ‘demanded new ways of seeing’ in a more active, engaged way in order to keep distant others ‘within ethical range’.22 Humanitarians transformed specific episodes of privation and suffering into humanitarian crises, commanding viewers’ attention via specific narratives and moral framings. In their campaigns, they articulated a distinct worldview that ‘forged communities of emotion and action … around specific causes’ by appealing to people’s sense of duty.23 But the humanitarian imagery must also be understood as part of a wider discourse of visual, instructive pedagogy and reform from the late nineteenth century onwards. Anna-Maria Hällgren claims that a ‘governing of vision’ privileged certain practices of looking that enabled otherwise problematic representations of social issues to become a valuable resource, creating upstanding citizens who were aware of their responsibilities to actively engage in curing social ills.24 The RB reporting worked in such a way as to engage the Swedish public and make them aware of their international charitable responsibilities to relieve the suffering of war children.

Recent works have explored how humanitarians in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century made extensive use of the new visual media, such as photographs, films and lantern slides, and how new visual cultures in turn helped drive the evolution of new mediated forms of humanitarianism and human rights activism, reaching out to save an ‘imagined humanity’.25 In this period, the picture (and especially the photograph) was often thought to break down distance and to offer a truer picture of suffering than words alone, thus helping instil sympathy towards distant others. Images demanded a specific affective approach that was key to the sense of moral outrage that could rally public opinion.26 New visual strategies of representation and communication thus gave rise to what Heide Fehrenbach and Davide Rodogno call ‘humanitarian imagery’, a kind of moral rhetoric that gave both ‘form and meaning to human suffering, rendering it comprehensible, urgent, and actionable for European and American audiences’.27

The body held a special place in this achievement. Visualizing the human body as vulnerable, endangered, in pain, or in recovery, was the imperative onlookers needed to recognize and respond to their moral duty to address human suffering.28 According to Laqueur, the humanitarian narrative created this kind of moral concern and action above all ‘by the pain of a stranger crying out—as if the pain were one’s own or that of someone near’ and ‘through this discourse of the body a common ground of feeling is established and the cognitive pathways for intervention laid in place’.29

As Friederike Kind-Kovács has argued in her study of the American Red Cross’s interwar relief work with Hungarian children, the First World War was ‘an indisputable turning point in the body’s politization’, making the destitute children’s bodies into a site of humanitarian intervention and a new political battlefield, both symbolic and real.30 Even if the suffering body had long been central to the humanitarian imagination and to the laws of war, the war years saw a more widespread focus on bodies of war in general, and the war-wounded body became a political object both valued and devalued.31 The dominant, gendered narrative of the war-torn soldier-body was supplemented with stories of other bodies at war, and the body of the innocent, vulnerable child played a prominent part in psychological warfare and propaganda.32

In analysing the humanitarian imagery of the RB in its early days, I will look at the interwar interventions in this ‘battlefield’, arguing that in the case of the RB, textual and visual narratives together formed a special humanitarian imagery around the suffering body of the war child. I will thus study the uses and meanings of both photographs and texts, and their intermedial entanglement. Even if textual accounts dominated over photographs, both forms of representation were very graphic, trusting to the reader’s vision and ‘inner sight’. Rhetorically, the campaigns emphasized the visual over the other senses. Descriptions focused on what the children looked like, their expressions, and how to respond to their demanding gazes. Metaphors of sight, the eye, and the eyewitness were frequently used to privilege a discourse of the visual. To quote a telling formulation in Stockholms Dagblad in January 1920, ‘The eyes of the whole world are fixed on Vienna’.33

Sensing war

I will start by examining how the war child’s suffering body was used, focusing on the humanitarian strategies of the RB, the intended reading of the narratives presented, and the making of an emotional community of Swedish war witnesses. Due to the lack of material, it is hard to say exactly how the terrible pictures of suffering affected individual readers, or the reception by a Swedish audience; however, we can say something about how the RB imagined—or wished—the reader, spectator, and donor would respond.

The invitation to readers to engage and participate involved both the humanitarian body and the body of the compassionate humanitarian public, pointing to the imagined attachment between the body of the child, the humanitarian reporter, and the Swedish audience. Following Laqueur, the personal body is ‘the common bond between those who suffer and those who would help’, the very basis of identification. The humanitarian narrative has the power to make readers feel the pain of the victim as if it were their own or that of someone close to them. Readers are asked to feel vicariously, through the body of the protagonist.34 The RB’s visual discourse thus used the humanitarian’s body as the medium between the victim and the donor. Readers were invited to walk the streets of Vienna and other cities, to step inside the hospitals and sanatoriums, lending their eyes and ears to the humanitarian.35 The affective and physical effects of seeing the war children’s bodies were vividly registered and described. In one report, the narrator depicted an overwhelming visit to a deprived Viennese hospital and how she was so taken by the encounter with the small suffering children that she had to turn away, silenced. She then underscored the severity of the situation by explaining that not even the paediatrician accompanying her could control his emotions, but cried silently.36 An interpretation of the situation in Vienna as ‘paralysing’, as one subheading had it, reinforced the supposed effect on the reader’s body when partaking of—and hence in—the terrible news.37

The humanitarian reporter or reporting humanitarian was an expression of a special type of turn-of-the-century reporter ideal, ‘the witness ambassador’, whose physical presence and embodied closeness to the stricken objects was crucial. Each used his or her own body as both a reference and an instrument. As the ‘ultimate witness’, the body was considered critical in giving evidence to the reader who could not be present. Reliability was created by accounts of the physical and emotional reactions of the reporter, whose body mediated the experiences. The body was supposed to be a reliable source of information about ‘the naked truth’, transcending conflicting opinions since it ‘could not lie’, and with sensations or reactions that were believed to make the testimony universally comprehensible.38

Thus the camera lens was not the only ‘humanitarian eye’ intended to establish realism and evidentiary truth claims. Framing humanitarianism as an eyewitness account was another opportunity to recognize its authority, accuracy, and authenticity. ‘The person writing this has herself spent several months this year in Vienna. I know, therefore, that the talk of the city dying is not a phrase, not a figure of speech, not an exaggeration, but reality’, the RB’s Elin Wägner wrote, and Alice Trolle repeatedly referred to ‘we down here in Vienna’, seeing the war children with her own eyes: ‘I have seen them in the wards of the hospital, where they rest in rows, bed after bed’.39 The rhetorical device of opening the sentence with ‘I have seen—’ was commonplace in the reports. Again, the primacy of seeing was confirmed. By referring to special correspondents and dating the reports as exactly as possible—‘Vienna, January the 26th’, ‘Vienna, December 1920’, ‘Vienna, January’, ‘Vienna at this very moment’—the narrative created a sense of historical accuracy, directness, and proximity to the events depicted, sometimes ‘hour by hour’.40

The humanitarian reporter was not only an observing witness, but also an emotional guide of sorts, directing the reader to react appropriately to the suffering bodies. Sight was the privileged sense here: the panoramas of the hungry were repeatedly referred to as ‘horror pictures’ and ‘horror images’.41 The public was frequently urged to look at (and then subsequently feel) the pain of the starving bodies: ‘As you can see the little one’s body is totally disfigured by starvation and suffering’, ‘Look at the pictures of the stunted children’s bodies on the front page!’, ‘Look at the little girl on the far left of our picture’.42 Newspaper readers were not only told where to look (instead of looking away), but also how to look. The act of witnessing, if only on the front page of a newspaper was also an assumption of responsibility: if you saw, felt, and knew, you would be obliged to take action. The responsibility to end the suffering was placed on ‘humanity’, but also more explicitly on those enjoying neutrality, especially the Swedes.43 Occasionally, it was even extended personally to the reader, rhetorically addressed as ‘you’: ‘Don’t you want to help an Austrian family in distress?’44

Shame and guilt were sometimes used to remind the public that helping the children was a long-term commitment. The RB’s checklist for the summer of 1920 was a strong emotional appeal in the face of possible compassion fatigue, addressed to a privileged Swedish ‘you’:

Remember the hundreds of thousands starving and suffering children in Austria, Germany, Hungary, Poland and Russia. Remember that while You enjoy Your well earned rest and the beautiful Swedish summer, at the same moment poor little innocent victims die, a death You could have prevented with Your gift. Your consideration. … Help must arrive now. For want, death, do not rest. Don’t forget it. Remember them now. … Remember that the suffering out there appeal to You, trust Your help!45

The narrative repeatedly appealed to sensibility rather than sense. It was, in a way, more performative than informative, trusting to emotional reaction over rational argument. Sight was the first and most important sense, but not the only one: touch and hearing were called for as well. The children’s bodies spoke directly to ‘the hearts’ of others: ‘The thought of these little innocent sufferers makes your heart ache.’46 When ‘we think of Vienna’, as Stockholms-Tidningen inclusively stated, ‘we’ were also expected and even instructed to instinctively ‘feel for the terrible destitution down there’.47 The liberal use of exclamation marks and the inclusive second person ‘we’ and ‘us’ was deliberate, forging an emotional community around the humanitarian reporter and her fellow witnesses. And the privileged feelings in this emotional community were compassion and sympathy, not horror, aversion, or sensationalism—and absolutely not anger or a yearning for revenge. Even if the sight of the children’s starving, filthy, and sick bodies were described as horrifying, they were nevertheless poignant, not repulsive. This was in obvious contrast to how the very same children were mediated in other contemporary media, such as the fiction short story.48

In order to work strategically, the humanitarian narrative must prompt identification.49 In the RB’s narratives, the focus was on the heart, on the passion that knowledge of the suffering body would arouse in the humanitarian public, who could hear and feel the pain as if the experience was their own or their children’s: ‘The cries; cries of horror, suffering and hunger, the cries of the distressed mothers, as they watched the life leaving the limbs of children who were once rosy and chubby … rang in the hearts of other mothers’.50 Upsala Nya Tidning took a similar line: ‘May all hearts that are capable of compassion, today be touched and honourably answer the overwhelming cry of distress from all these vast realms of despair. … Save the Children!’51

Representing war

Part and parcel of the RB’s humanitarian emotional strategies were the representational aspects of the organization’s humanitarian imagery, and the kind of meanings and memories of war that were inscribed in the body of the war child. I would argue that the starving child’s body represented the remains of war, and served as a reminder of its horrors. The legacy of war was engraved on the child’s skin and bones, and to see such suffering was also to recognize the wider victimizing consequences of the First World War for (European) humanity. By envisaging the child’s body as both temporally and geographically trapped by war, the traumatic experiences of total war were visualized for a Swedish audience.

Even though I have analysed the textual and visual representations of the child’s body together as a unit—much as it was presented to contemporary newspaper readers—it is important to note some media specifics. While prominent members of the RB signed many of the reports, there was no reference to photographers, photo agencies, or the specific context in which the pictures were originally taken, produced and circulated, with one exception.52 In contrast to the detail of the texts, the pictures are generally bare of historical detail, and the children portrayed are all anonymous. Other dissimilarities worth noting are the gendered overrepresentation of the suffering boy in the visual material (unlike the texts), indicating either that the Swedish audience was more sensitive to male suffering, or that the sight of an emaciated, naked boy’s body was more socially acceptable than a girl’s. Another example of the divergence of the textual and visual narratives was that parents and families were frequently part of the texts,53 while the child in the humanitarian photographs was usually alone, pictured without recognizable relatives or even adults. According to Fehrenbach, the total focus on the lone child was a novelty in the humanitarian imagery of children, largely invented by Save the Children’s interwar campaigns.54

The child’s body as traumatic memory

Contemporaries considered the First World War to be a profound rupture in the linear history of progress. Later historians have conceived of the war as a traumatic, collective, ‘borderline event’—a radical disruption that destabilized all sense of historical continuity, fracturing the link between past and future.55 In the RB’s humanitarian imagery, the child’s body was used to tell of the war’s reversal or even perversion of time—of its ability to transcend temporality—through the lasting negative impact on natural biological development and the normal chronology of childhood. The legacy of war was inscribed on the bodies of its children in many enduring ways. The post-traumatic effect of war, disturbing and disrupting the normal phases of progression, was twofold: either the children’s bodies were stunted, underdeveloped, and they regressed, or they were prematurely aged. In early 1920, the RB quoted a doctor stating that all Austrian children were undersized: ‘four or five years behind for their age, and all had big swollen heads, stoops and big tummies’.56 They generally appeared to be years younger than their biological age: five-year-olds looked like one-year-olds, and one-year-olds looked like newborns.57 Not only did the children look younger than they were, they also behaved like infants. Their bodies were regressing instead of growing. Parents and doctors confirmed that children who had once been able to walk, talk, and play were now paralysed, mute, and passive.58 The massive resurgence of small bodies broken by diseases such as rickets and tuberculosis was seen as yet another sign of the retrogradeness of war: Central Europe was plunged back into the nineteenth century, a whole generation of progressive health work lost.59

The counterpart, the prematurely aged body, instead had the look and pains of the elderly: ‘I have seen eight-year-old girls look like dwarf women the size of a three-year-old, with heavily wrinkled foreheads and mouths and a smile so heartbreakingly sad it made me cry’, Wägner testified, and continued, ‘The poor little skeleton enclosed in empty, wrinkled, bluish skin. Their faces have a weird, old, timeworn, and suffering expression. It seems as if these strange creatures have a thousand years of suffering behind them.’60

The regressed body and the prematurely aged body were explicitly linked to the war, for it was the war that had ‘deeply disturbed the delicate organisms of the children’, and dislocated the biological from the chronological.61 The children had stopped growing or had aged too fast due to undernourishment and trauma caused by the war; their bodies were still caught in the conflict. Discussing the shell-shocked veteran’s body in similar terms, Jay Winter suggests that the disturbing character of such images ‘lay both in the body of the sufferer and in the gaze of the onlooker. Together they (and we) share embodied memory’.62 The shell-shocked soldier’s body and the deformed war child’s body both told war stories, for embodied memory was inscribed in them. For them, the war was not over. It carried on regardless in their stunted and disrupted—or aged and withering—bodies, both rewinding and fast-forwarding their normal, gradual development: ‘The war is over. But the misery that the war has created continues. People in the war-ravaged countries are eaten away by hunger and want. The children are least resistant and hardest effected. Three million will be lost this winter’.63 In this way, the RB challenged the established war narrative, both the conventional periodization of the First World War (when it ended, whether it was over, and in that case for whom), and which kinds of bodies and bodily harm counted as war invalids and war injuries, and thus rendered the sufferer a deserving war victim. Like the narrative of shell shock, it disrupted the heroic narratives of war and challenged conventional interpretations of the war’s meaning, questioning the temporality of antebellum and postbellum. The traumatic memory of arrested demobilization that both the shell-shocked soldier and the regressed or aged child embodied was circular or fixed, not linear.64

As a prolonged war with no foreseeable end ravaged it, body and soul, the symbolic figure of the child was not only constructed as a representation of a better post-war future—as earlier research has noted—but also as the remnants of a dark past, dragging the traces of war with it, a ticking bomb of physical and mental degeneration.65 Not only had the brutality of the greatest war in history halted the evolution of children, it had also halted or even ended the strong prewar belief in constant progress and the linear development of mankind with the Europeans in the van. Like its children, the continent now seemed to be moving backwards instead of leading the way.66 The RB’s many stories of deformed children’s bodies were part of this larger narrative, commenting on the terrible loss of (European) humanity and superiority. The RB narrative left it open to the onlooker to decide which side would win, cautioning that now was a fatal time of direst emergency that would determine the future of humanity. Privileging the children as the most worthy and precious war victims was the key to peace, and, again, the viewer was invited to intervene. If only the Swedes would give the RB the means to act quickly, the organization had the power to bring the war to a definitive end by reconstructing the children, hence setting time right.67

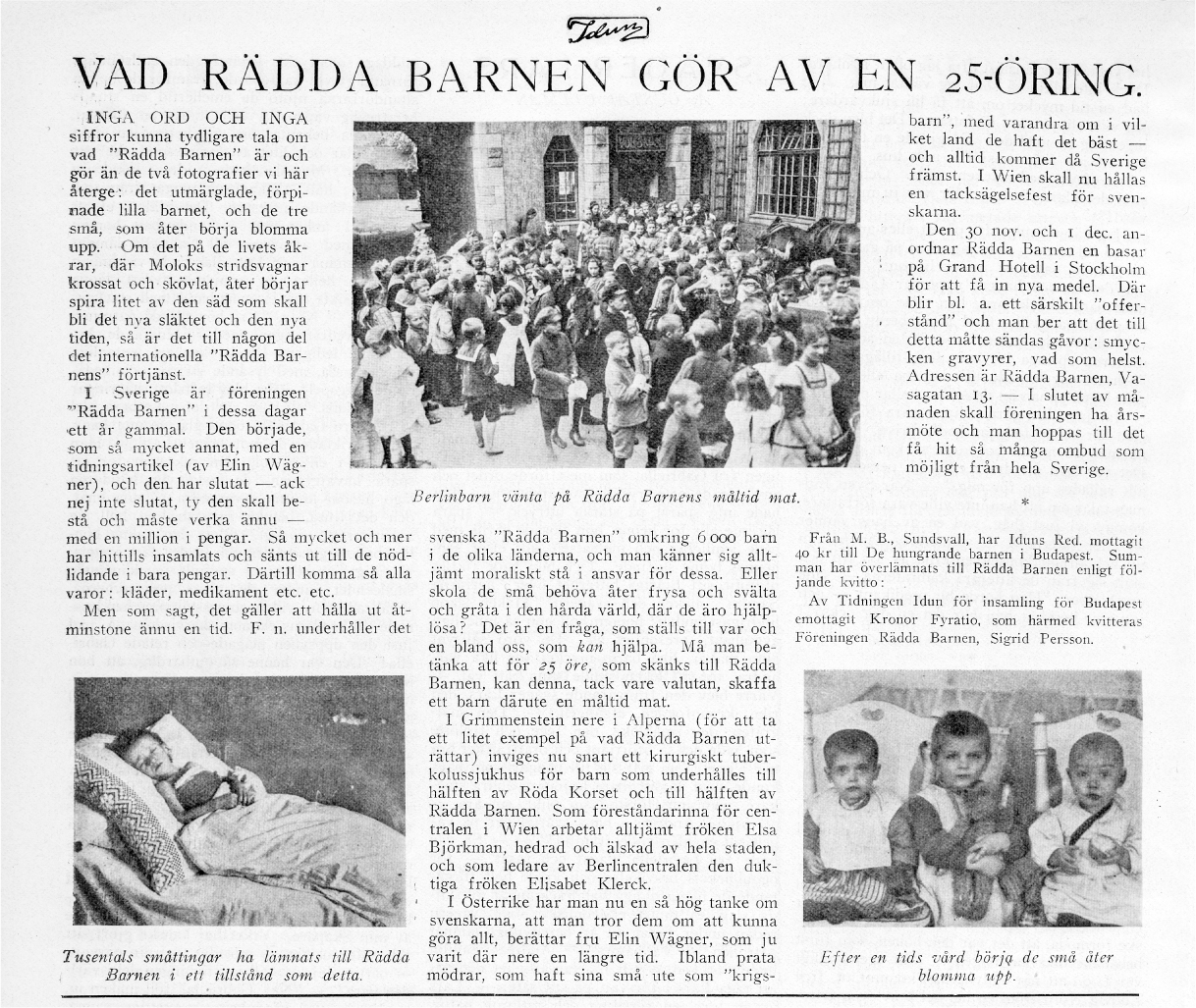

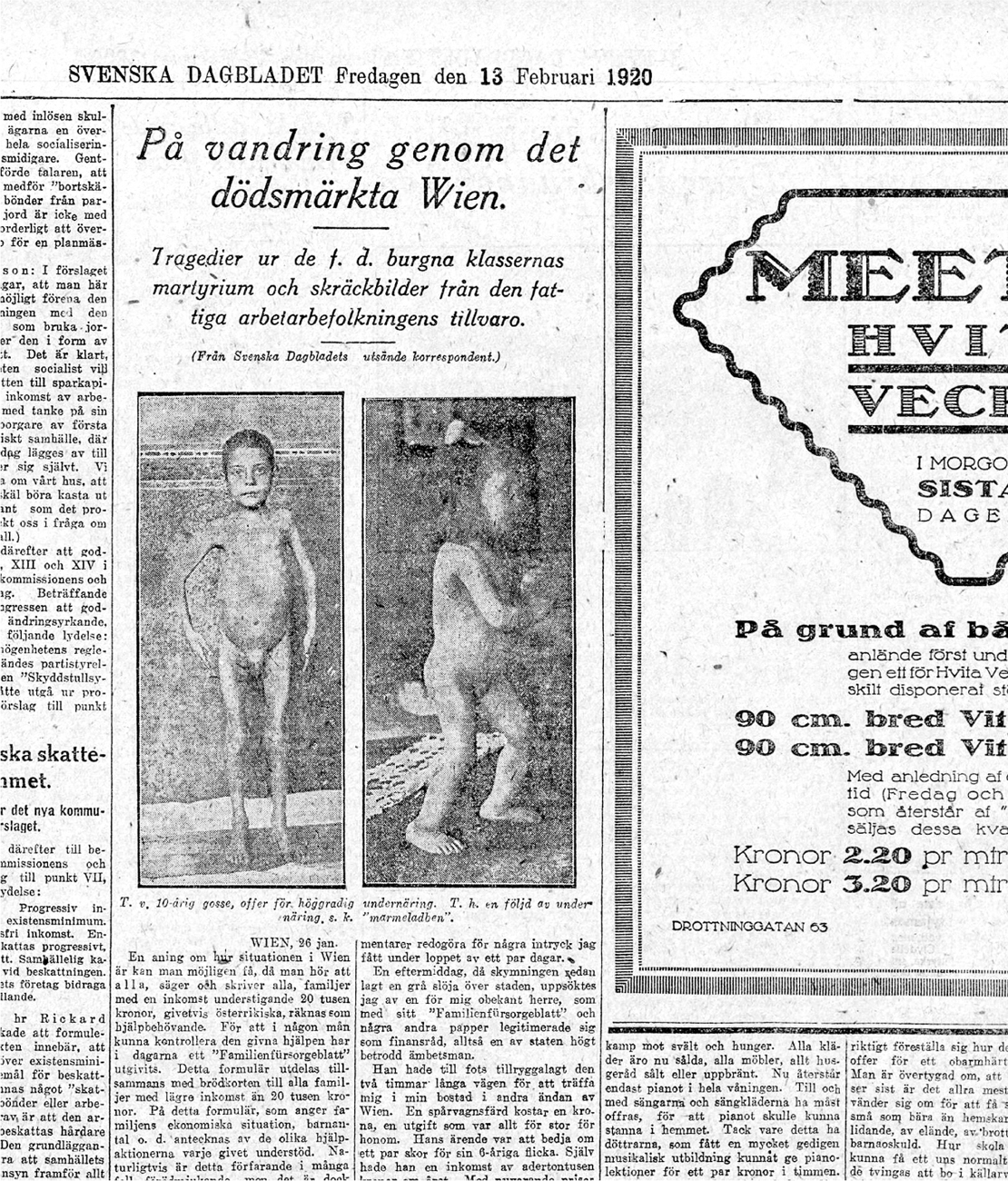

The humanitarian mending of time by reshaping and regenerating the child’s body was captured in the illustrated women’s magazine Idun in 1920, which wanted to convince its readers of the success story that was the humanitarian work done by the RB by an illuminating comparison before and after. The before and after was a long-standing photographic convention and rhetorical strategy employed by businesses and humanitarians alike.68 In the RB language, it compared the (nearly) lost and the saved. The before image in Idun was of an emaciated, helpless child with its eyes shut, sitting in a hospital bed; after showed three neatly dressed toddlers facing the camera, seated on chairs with toys laid out in front of them. The one in the middle, almost smiling, cuddled a teddy bear. The introduction to the article conveyed the typical conviction in the power of the testimony of the photograph: ‘No words, no figures can better speak of what Save the Children is and does than the two photographs below: the emaciated, tormented little child, and the three little ones who have once again begun to flourish.’69 This way of displaying the children’s bodies first before and then after feeding, nursing, and clothing them amounted to a visual affirmation of success, a way of literally showing their progress to the audience and attracting new donors, while at the same time such fundraising advertisements also ‘metaphorically placed the responsibility to continue to feed starving children in the hands of the viewer’.70 Finally, the before-and-after imagery can be seen as a way for humanitarianism to come to grips with wartime and overcome it by giving the saved child back its proper peacetime body and childhood. Seeing and saving children thus became peacemaking of both a literal and a figurative kind.

‘What Save the Children can do with a five pennies’ (‘Vad Rädda Barnen gör av en 25-öring’), Idun, 21 Nov. 1920. Image reproduction: UB Media, Lund University Library.

The sight and site of battle

As we have seen, the emaciated body of the child served the narrative purpose of being a sight—a visible memory in a temporal sense, a screen onto which the spectator could project a lost past and possible futures.71 But the starved, sick, and crippled body was also a site in spatial terms, ‘a space where violence is done’, to follow Aubrey Graham.72 The scarred body was seen de facto as the site of battle, pictured as ‘ravaged’, ‘totally broken’, and ‘beaten to the ground’.73 The Swedish press captured the insecurity and instability of demobilization in headlines and catchphrases such as ‘marmalade children’ for children suffering from an extremely painful form of rickets practically unknown before the war, which made the skeleton ‘so loose and swampy that it cannot support them’.74

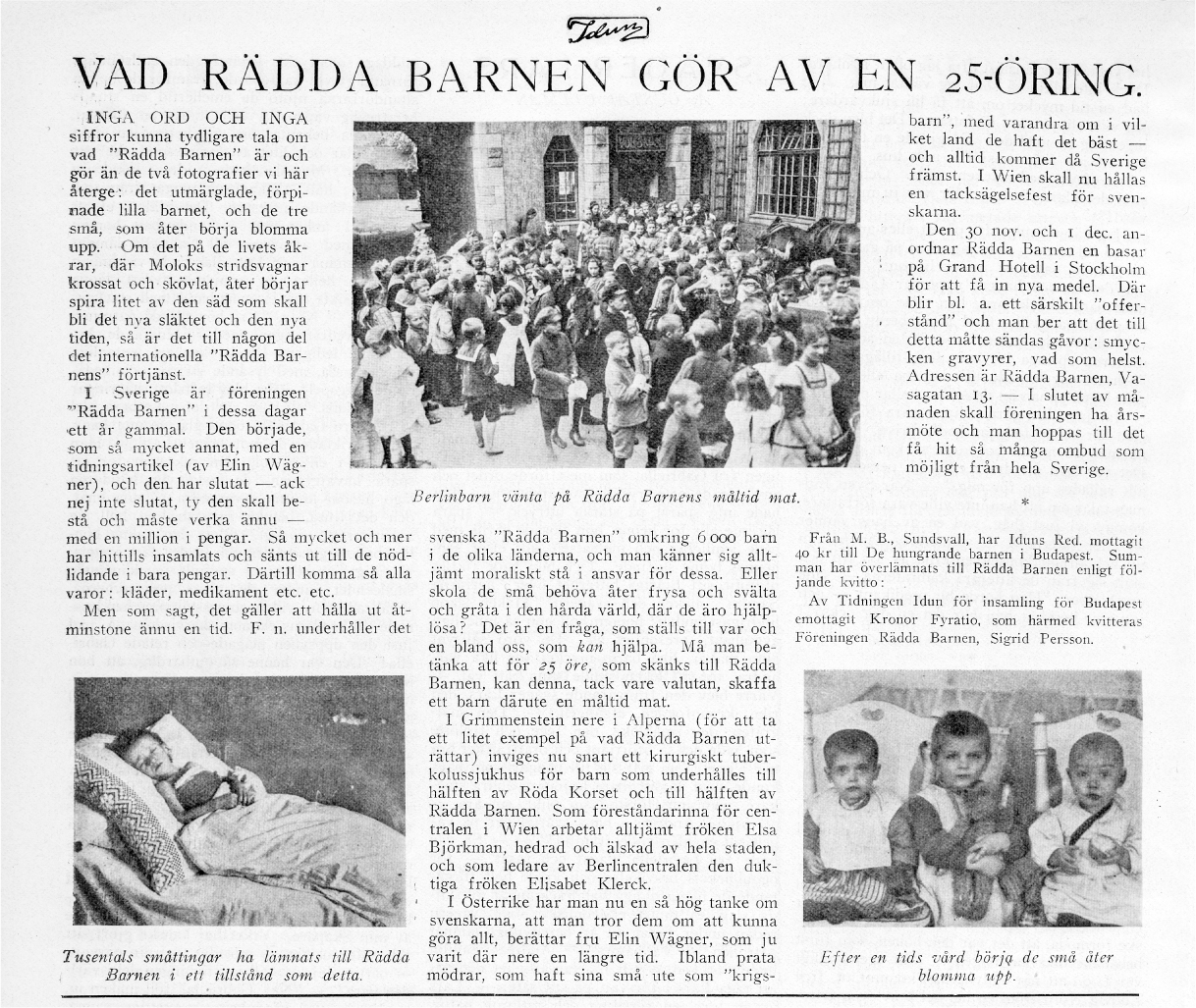

In Svenska Dagbladet’s report ‘A walk through a doomed Vienna’, a centred diptych of a naked boy and girl accompanied the graphic descriptions of disfigured war-marked bodies. Both pictures were examples of what Graham has identified as one of the two commonest visual tropes of ‘humanitarian crisis imagery’ at the time: the closely cropped portrait, set against a neutral background that draws attention to the victimized body. This type of body-centred, decontextualized portrait was assumed to ‘speak for itself’, in the sense that it did not need a caption to guide the reader as to the atrocity depicted.75 However, this did not apply in the Swedish case. First the headline indicated how to read the (possible) fate of the two children portrayed—all hope is despaired of. The caption then added that the photograph to the left showed ‘a ten-year-old boy, a victim of extreme undernourishment’. It was a full-length portrait of a naked, emaciated boy, his bony arms outstretched to emphasize his swollen tummy and the empty void behind him. His bare skin and genitals underscored his bodily vulnerability and exposure, a nakedness that also served to highlight the physical contours of starvation. He looked firmly into the lens, facing the viewer with an accusing look. This visual device of the child gazing back at the spectator encouraged a certain way of viewing the image. The sense of having eye contact enhanced a feeling of directness, presence, and proximity to the victim, and hence a sense of obligation towards him.76 The photograph to the right was also a full-length portrait, but in profile and closer up, and showed a little girl who was naked except for a bow in her hair. Her features were blurry and almost invisible. Instead of the typical marks of starvation—big belly, thin limbs, hollow face—the focus was on her awkwardly wobbly legs and feet. It looked as if she was being held up by the humanitarian hand extended to her. The reader was then told that this rickety girl was yet another ‘consequence of undernourishment, suffering from so-called “marmalade legs”.’77

Another example of a humanitarian portrait of a sick and starving child’s body as a site of battle was published in the weekly magazine Veckojournalen, and showed an infant, perhaps aged about one. A wrinkly, skinny baby was held up as evidence for the camera, crying, with his mouth and eyes wide open. A doctor in a white robe supported the baby with one hand placed under his bottom and the other around his swollen belly. What seemed to be a woman’s hand reached in from the left of the picture, holding the crying baby’s right hand. The position of the three hands drew the spectator’s attention to the boy, as did the doctor’s eyes and face, which were fixed on the baby and not the camera: the little boy was the only one gazing back. The caption read ‘A German child has got rickets due to undernourishment. The look in the little one’s tearful eyes should say more than words.’ It certainly bore witness to a confidence in the morality of sight, while at the same time its sheer existence paradoxically denied the common humanitarian idea that ‘their bones/flesh speak’ for themselves.78 The additional information in the headline also referred to the baby as ‘beaten’ and ‘defeated’, using warlike metaphors.79 This photograph thus functioned as a photographic proof for Swedish readers of the violations of the human body by war, ‘a kind of forensic evidence’ of brutality, an inconvertible visual verification that atrocities were occurring.80 Such images of victimized bodies served a dual purpose as evidence and as emotional provocation to provide factual and visceral explanations for readers.81 With such direct, naked, and distressing imagery, the Swedish public would be moved to act.

The report ‘A walk through a doomed Vienna’ (‘På vandring genom det dödsmärkta Wien’), by Gerfred Mark (Gerda Marcus), Svenska Dagbladet, 13 Feb. 1920. Image reproduction: UB Media, Lund University Library.

Miggs (signature), ‘Fight for the defeated’ (‘Ett slag för de slagna’), Veckojournalen, 16 May 1920. Image reproduction: UB Media, Lund University Library.

In contrast to Graham’s findings, the body-centred humanitarian crisis portraits used by the RB did not stand alone, or at least not in the daily and weekly press. Instead, powerful headlines, headings, and captions helped the reader to see, and hence feel, the motif in the right way. This was especially important when the press photographs were poor quality or blurred—they were frequently announced as ‘touching’ or as an ‘appeal to our compassion’.82 The reader was never left to look unguided; always the gaze was directed to the chosen meanings and effects of the humanitarian imagery.

The RB’s humanitarian imagery can thus be summed up as the picture of a passive, weak, and vulnerable child, an innocent war victim waiting to be saved. The children so portrayed were mostly inactive: staring, lying, sleeping, being carried or held up, unable to support themselves. The headlines, like the photograph captions, led the reader to interpret the children as victimized by referring to them as tortured, crying, fading, lost, beaten, defeated, dying. Their bodies were framed with passive tropes, ‘marked as victims by their bodily lack’ of strength and ability.83 Their gaze was decoded as engaging and appealing, not accusing or demanding. They were represented as victims there to plead the humanitarian cause rather than claimants in their own right.84 The practices of looking thus sometimes came close to what Hannah Arendt calls a ‘politics of pity’ towards the misfortunate, rather than an act of solidarity with the suffering.85

Even if simplicity and directness of emotional address instead of political causation were, at least in part, in the very nature of humanitarian imagery,86 and even if the RB’s strongly sensory, affective reporting sometimes came close to a ‘politics of pity’, such images at the same time helped to put children on the international agenda and encouraged the idea of children’s rights. In 1924, the Geneva Declaration of the Rights of the Child was adopted by the League of Nations, largely due to the activism of the International Save the Children Union, of which the RB was an active part.87 In its Swedish media campaigns, the RB used the ‘moralizing icon of the child’ to underscore that the deformed body was not a result of natural disasters or epidemics, but a sight and site of war violence, thus questioning the usual image of war victims and their rights.88 Bruno Cabanes has suggested that it was exactly the recognition of the other’s victimized body that would be the starting point for the imagining of a common humanity—‘a coalition of pain’—after the extreme nationalization of bodies in the First World War, and for the rethinking of individual, universal human rights.89

It is worth noting which purposes the child’s body was not expected to serve in the RB’s humanitarian imagery. The most notable absence from the many depictions of war-ravaged bodies in its media campaigns was the dead body, the corpse. The closest it came was when the children were represented as ‘the living dead’, ‘ghosts’, or ‘skeletons’, as liminal bodies in between life and death, balancing ‘on the brink of the abyss’.90 When the RB did mention death, it was collective and depersonalized. The dead were abstracted into statistics and figures—tables of birth and death rates, survival percentages, daily numbers of deaths and estimated casualties to come, or hidden in vague or sweeping phrases such as ‘mass death from starvation’ or ‘unparalleled mortality’.91 This is striking, since we know that other relief organizations at the time did publish accounts and photographs of dead children. According to the literature, the war years wore down opposition to public representations of violence in the media, and also changed the rules for portraying suffering in charitable publications, resulting in a more commercialized, sensationalist, and spectacular humanitarianism. The British SCF, for example, was infamous for its early use of shocking images.92 Why, then, did its Swedish sister organization refrain from ‘seeing the dead’? Since there is no principled discussion to be found in the sources, it is hard to tell whether it was for reasons of access or the result of an editorial choice. Perhaps the Swedish press—the organization’s main public channel—was cautious about publishing such images, which might have been more shocking in a country that had been spared open war.93 The RB might also have been wary of being accused of the sensationalism of the SCF, fearing that it might do more harm than good to their cause. If Kevin Rozario is right when he claims that ‘Humanitarian texts have always been sites for encountering horror’, and that there is only a blurred line between the humanitarian and the ‘atrocitarian’ gaze, the RB nevertheless shied away from depicting dead children.94 The dead body was indeed a powerful device, one that could communicate a strong anti-war message,95 but it was also a horrible sight that risked eliciting unwanted reactions: revulsion, alienation, hopelessness, and a desire for revenge. Instead, the RB activists directed its readership to the survivors, focusing its all on the victims who could be saved.

Conclusion

This chapter discusses the strategic, representational uses and meanings of the suffering war child’s body in Rädda Barnen’s (Swedish Save the Children) media campaigns in the aftermath of the First World War. I have examined the visual and visualizing discourse privileged within this kind of humanitarian reporting as a kind of moral rhetoric, which was designed to instruct Swedish readers how to view the images in committed, compassionate ways and ultimately to ameliorate the sufferings of war by donating to the RB or by becoming an activist. My focus is the functioning of the emblematic sight of a child’s warstuck body when sensing, imagining, and questioning total war and its consequences.

The experience of the First World War altered the frames of war, bringing civilian victims and marginalized groups such as children to the fore. According to Laura Sjoberg, it is only on war’s margins that we can understand war itself. War, the daily experience that long predates and post-dates what is traditionally defined as war, fought in non-standard arenas by non-standard combatants (and not by soldiers, men, governments), has its own invisible violence beyond the traditional battlefield.96 The RB’s interwar media campaigns are one such alternative way of telling war histories. In the organization’s humanitarian reporting, war was represented as a continuum rather than as an event: its narrative repeatedly challenged the conventional periodization in which the war ended in 1918. For the children of Vienna and other ‘haunted places’, the war raged on in their bodies and minds, in many cases worse than during the ‘actual’ war.97 The physical marks of hunger—the starving, stunted, sickly body—were thus used to contest conceptions of ‘war’ and ‘post-war’, demobilization and restoration. War remained in the children’s bodies, the visual remains—and reminders—of the horrors of war. But the textual and visual narratives also extended the reach of war, siting it in the daily suffering in icy cellars and dark streets of the post-imperial metropolis, far from the trenches. Humanitarian reporting, meanwhile, tried to direct the Swedish public’s gaze towards the smallest and often least visible victims of war, and with it change the main characters in the narrative. Obviously, the RB did not use concepts such as ‘human security’ or ‘food insecurity’, but the organization certainly considered starvation one way both to wage and to feel war. The sensory experience of hunger—its outcome mediated to Swedish readers by the humanitarian war witnesses’ accounts in the press—was accounted an experience of war.

By visualizing the suffering child as a signifier of total war, placing its war-torn body at the centre of a humanitarian imagery and projecting it onto the front pages of the daily papers, the RB thus took part in what Jay Winter has called a ‘war of narratives’ between competing, contradictory, and unsettled war memories during demobilization.98 Although the humanitarian, visual discourse of the RB was clearly discursively linked to other war narratives of the soldier–victim and ‘the lost generation’, it did not primarily foreground loss and disillusion. Humanitarian journalism stood for a more activist and progressive anti-war agenda, a way of getting out of war and hopefully leaving it behind for good by rescuing future generations. It was not only about remembering war, but also about forgetting. By keeping its eyes wide shut, focusing on survivors rather than dead children, it tried to encourage hope, faith, and confidence in the ‘humanitarian heart’ that some of what had been lost in war could yet be saved.

Notes

1 Alice Trolle, ‘De små martyrerna’, Svenska Dagbladet, 23 Jan. 1920.

2 Ellen Key’s Barnets århundrade was first published in 1900. This highly influential work on children and childhood was translated into 26 languages, in English as The century of the child (1909). Key was a keen supporter of Save the Children—see ‘Vad kända män och kvinnor tänka om Rädda Barnen’, Rädda Barnen, 6 (1920).

3 Trudi Tate, Modernism, history and the First World War (Manchester: MUP, 1998), 95; cf. Kevin McSorley (ed.), War and the body: Militarisation, practice and experience (London: Routledge, 2013); Christine Sylvester, War as experience: Contributions from international relations and feminist analysis (London: Routledge, 2013); Nicholas J. Saunders & Paul Cornish (eds.), Bodies in conflict: Corporeality, materiality, and transformation (New York: Routledge, 2014).

4 Julia Irwin, Making the world safe: The American Red Cross and a nation’s humanitarian awakening (Oxford: OUP, 2013), 12.

5 Branden Little, ‘An explosion of new endeavours: Global humanitarian responses to industrial warfare in the First World War era’, First World War Studies, 5/1 (2015), 13. The term ‘dynamic of destruction’ comes from Alan Kramer, Dynamic of destruction: Culture and mass killing in the First World War (Oxford: OUP, 2007). For the world wars as turning points in the emotional history of compassion, see Michael Barnett, Empire of humanity: A history of humanitarianism (New York: Ithaca, 2011), 15, 28–9; Bruno Cabanes, The Great War and the origins of humanitarianism, 1918–1924 (Cambridge: CUP, 2014), 3, 10, 304; Keith David Watenpaugh, Bread from stones: The Middle East and the making of modern humanitarianism (Berkley & Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2015); Friederike Kind-Kovács, ‘The Great War, the child’s body and the American Red Cross’, European Review of History-Revue Européenne d’Histoire, 23/1–2 (2016), 33; Friederike Kind-Kovács, ‘The “other” child transports: World War I and the temporary displacement of needy children from Central Europe’, Revue d’histoire de l’enfance ‘irrégulière’, 15 (2013), 75–109.

6 For an overview, see the special issue on humanitarianism in the era of the First World War in First World War Studies, 5/1 (2015); Little 2015; Branden Little, ‘Humanitarian relief and the analogue of war’, in Jennifer D. Keene & Michael S. Neiberg (eds.), Finding common ground: New directions in First World War studies (Leiden: Brill, 2011), 75–101; Irwin 2013, especially 213–14, n. 2, n. 5; Cabanes 2014; Watenpaugh 2015; William I. Hitchcock, ‘World War I and the humanitarian impulse’, Tocqueville Review/La revue Tocqueville, 35/2 (2014), 145–63; for the history of humanitarianism, human rights, and world war, see Cabanes 2014, 6, 9–11,17, 301. I can only agree with Cabanes’s remark that the history of humanitarianism and human rights ought to be read together with the cultural history of war, as intertwined rather than separate.

7 Little 2015, 11.

8 Emily Baughan, ‘Every citizen of empire implored to Save the Children! Empire, internationalism and Save the Children in interwar Britain’, Historical Research, 86/231 (2013), 116–37; Clare Mulley, The woman who saved the children: A biography of Eglantyne Jebb, founder of Save the Children (Oxford: Oneworld, 2009); Linda Mahmood, Feminism and voluntary action: Eglantyne Jebb and Save the Children 1876–1928 (London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2009); Cabanes 2014, 248–99.

9 The RB archive is held by the Swedish National Archives and consists of press clippings from the daily and weekly press, commercial campaign material (flyers, leaflets, advertisements, memos, photographs), and minutes from the RB board of directors: Riksarkiven, Stockholm (RA), Förenings- och organisationsarkiv (73), Rädda Barnens riksförbund, Rädda Barnen 1985, Samlingsserie övriga handlingar F1f: 2. 1920–50-tal diverse trycksaker; RA, Förenings- och organisationsarkiv (73), Rädda Barnens riksförbund, Rädda Barnen 2005, Övrigt Pressklipp Ö1, 1–6, 1919–1923; RA, Förenings- och organisationsarkiv (73), Rädda Barnens riksförbund, Rädda Barnen 1985, Samlingsserie övriga handlingar F1f: 1. 1920–1949 Medlemstidning 1920–26. See the minutes of the RB board of directors, RA, Förenings- och organisationsarkiv (73), Rädda Barnens riksförbund, Rädda Barnen 2005, Styrelsen A2:1 1920–1922 Kartong (protokoll styrelsesammanträden), 8 Dec. 1920, 11 Mar. 1920, 9 Jan. 1921, 27 Jan. 1921, 8 Feb. 1921, 11 Mar. 1921, 22 Mar. 1921, 31 May 1921, 19 Oct. 1921, 8 Nov. 1921, 22 Nov. 1923. See also ‘Vad Rädda Barnen gör av en 25-öring’, Idun, 21 Jan. 1920; Elsa Björkman-Goldschmidt, ‘Så var det i Wien’, in Vera Forsberg, Att rädda barn: En krönika om Rädda Barnen med anledning av dess femtioåriga tillvaro (Stockholm: Rädda Barnen, 1969), 117–21.

10 Lina Sturfelt, ‘Humanitarianism (Sweden)’, in Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer & Bill Nasson (eds.), 1914-1918-online: International Encyclopedia of the First World War (Berlin: Freie Universität Berlin, 2018-01-22), DOI: 10.15463/ie1418.11214; Lina Sturfelt, Eldens återsken: första världskriget i svensk föreställningsvärld (diss.; Lund: Sekel, 2008), 208–209; Mats Rohdin, ‘När kriget kom till Sverige: första världskriget på bioduken’, Biblis, 68 (2015), 13–15.

11 Lina Sturfelt, ‘From parasite to angel: Narratives of neutrality in the Swedish popular press during the First World War’, in Johan den Hertog & Samuël Kruizinga (eds.), Caught in the middle: Neutrals, neutrality and the First World War (Amsterdam: Aksant, 2011), 105–120; Sturfelt 2008; Monika Janfelt, ‘Svensk krigsbarnsverksamhet 1919–1922’, Historisk tidskrift för Finland, 75 (1990), 465–98; Monika Janfelt, Stormakter i människokärlek: Svensk och dansk krigsbarnshjälp 1917–1924 (diss.; Åbo: Åbo akademi, 1998).

12 For the RB’s own accounts of its early history, see, for example, Minnesskrift över föreningen Rädda Barnens 20–åriga verksamhet i Sverige, 1919–1939 (Stockholm: Rädda Barnen, 1939); and Vera Forsberg, Att rädda barn: En krönika om Rädda Barnen med anledning av dess femtioåriga tillvaro (Stockholm: Rädda Barnen, 1969). There is very little historical research on the RB, the one notable exception being Ann Nehlin, Exporting visions and saving children: The Swedish Save the Children Fund (diss.; Linköping: Department of Child Studies, 2009), which however is limited to 1938–1956.

13 Stefan Ludwig Hoffmann, ‘Gazing at ruins: German defeat as visual experience’, Journal of Modern European History, 9 (2011), 328–50.

14 On hunger as news and the media’s role in making humanitarian crises into media events, see Christina Twomey, ‘Framing atrocity: photography and humanitarianism’, History of Photography, 36/3 (2012), 255–8; James Vernon, Hunger: A modern history (Cambridge: Belknap, 2007); Heide Fehrenbach & Davide Rodogno, ‘Introduction: The morality of sight: humanitarian photography in history’, in Heide Fehrenbach & Davide Rodogno (eds.), Humanitarian photography: A history (Cambridge: CUP, 2015), 2–6; Sharon Sliwinski, ‘The childhood of human rights: The Kodak on the Congo’, Journal of Visual Culture, 5/3 (2006), 342, 365; Sharon Sliwinski, Human rights in camera (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011); Cabanes 2014, 303–304. The mediation of contemporary humanitarianism is a huge field. See Lilie Chouliaraki, ‘Afterword: The dialectics of mediation in “distant suffering studies”’, International Communication Gazette, 77/7 (2015), 708–714; Shani Orgad & Irene Bruna Seu, ‘The mediation of humanitarianism: Toward a research framework’, Communication, Culture & Critique, 7 (2014), 6–36; Luc Boltanski, Distant suffering: Morality, media and politics (Cambridge: CUP, 1999).

15 Johan Jarbrink, Det våras för journalisten: Symboler och handlingsmönster för den svenska pressens medarbetare från 1870-tal till 1930-tal (diss.; Mediehistoriskt arkiv, 11; Stockholm: Kungliga biblioteket, 2009), 181.

16 Heide Fehrenbach, ‘Children and other civilians: photography and the politics of humanitarian image-making’, in Fehrenbach & Rodogno 2015, 167–8, 174–5, quote at 167; Kevin Rozario, ‘“Delicious horrors”: Mass culture, the Red Cross, and the appeal of modern American humanitarianism’, American Quarterly, 55/3, (2003), 420–21, 430; Fehrenbach & Rodogno 2015, 11; Twomey 2012, 256–8; Little 2015, 5; Thomas D. Westerman, ‘Touring occupied Belgium: American humanitarians at “work and leisure”’, First World War Studies, 5/1 (2015), 43–53. There are many notable, sometimes literal, similarities regarding the imagery and metaphorical language of the humanitarian reports cited by Kind-Kovács (2016, 37–8) and in my Swedish material, making the humanitarian narrative genre and humanitarian journalism of the interwar years an interesting avenue to explore.

17 Westerman 2015, 50; Kind-Kovács 2016, 38, 33–4: cf. Fehrenbach 2015, 167, 176–7; Silvia Salvatici, ‘Sights of benevolence: UNRRA’s recipients portrayed’, in Fehrenbach & Rodogno 2015, 210–11; Irwin 2013, 144, 167; Cabanes 2014, 52.

18 See minutes of the RB board of directors, RA, Förenings- och organisationsarkiv (73), Rädda Barnens riksförbund, Rädda Barnen 2005, Styrelsen A2:1 1920–1922 Kartong (protokoll styrelsesammanträden), 8 Dec. 1920, 11 Mar. 1920, 9 Jan. 1921, 27 Jan. 1921, 8 Feb. 1921, 11 Mar. 1921, 22 Mar. 1921, 31 May 1921, 19 Oct. 1921, 8 Nov. 1921, 22 Nov. 1923; see also ‘Vad Rädda Barnen gör av en 25-öring’, Idun, 21 Jan. 1920; Elsa Björkman-Goldschmidt, ‘Så var det i Wien’, in Forsberg 1969, 117–21; for Elgström, Stiernstedt, and Wägner and their anti-war writing, see Sofi Qvarnström, Motståndets berättelser: Elin Wägner, Anna Lenah Elgström, Marika Stiernstedt och första världskriget (diss.; Möklinta: Gidlund, 2009), and her chapter in the present volume.

19 Fehrenbach & Rodogno 2015; Twomey 2012, 256–6; Sliwinski 2011.

20 Rozario 2003, 421, 425–6.

21 Fehrenbach 2015, 193.

22 Thomas W. Laqueur, ‘Mourning, pity, and the work of narrative in the making of humanity’, in Richard Ashby Wilson & Richard D. Brown (eds.), Humanitarianism and suffering: The mobilization of empathy (Cambridge: CUP, 2009), 8.

23 Fehrenbach & Rodogno 2015, 4.

24 Anna-Maria Hällgren, Skåda all världens uselhet: Visuell pedagogik och reformism i det sena 1800-talets populärkultur (diss., Möklinta: Gidlund, 2013).

25 Twomey 2012, 255–9; Sliwinski 2006; Sliwinski 2011; Fehrenbach & Rodogno 2015, 2–6; Gary J. Bass, Freedom’s battle: The origins of humanitarian intervention (New York: Knopf, 2008), 5–9, 25–8; Brendan Simms & D. J. B. Trim, Humanitarian intervention: A history (Cambridge: CUP, 2011), 22, 389–90; Davide Rodogno, Against massacre: Humanitarian intervention in the Ottoman Empire 1815–1914 (Princeton: PUP, 2012), 15–16, 268–9.

26 Sliwinski 2006, 334, 342, 346; Fehrenbach & Rodogno 2015, 1; Twomey 2012, 256.

27 Fehrenbach & Rodogno 2015, 2–6, quote at 4.

28 Ibid. 15–16.

29 Laqueur 1989, 180, 190, original emphasis.

30 Kind-Kovács 2016, 37–8, quote at 37.

31 Ana Carden-Coyne, ‘Gendering the politics of war wounds since 1914’, in Ana Carden-Coyne (ed.), Gender and conflict since 1914 (Houndsmill: Palgrave Mac-Millan, 2012), 5, 83, 95; Joanna Bourke, Dismembering the male: Men’s bodies, Britain and the Great War (London: Reaktion, 1996); Tate 1998, 80, 84–5, 95; Cabanes 2014, 6.

32 Tate 1998, 24, 41–50, 59–61; Rozario 2003, 419; Cabanes 2014, 272–3, 283–4, 297–8; Stéphane Audoin-Rouzeau & Annette Becker, 14–18: Understanding the Great War (New York: Hill & Wang, 2003), 110–112; James Marten (ed.), Children and war: A historical anthology (New York: NYUP, 2002).

33 ‘Där köld och svält dagligen kräva offer’, Stockholms Dagblad, 7 Jan. 1920.

34 Laqueur 1989, 177, 179, 180, 183, quote at 177.

35 See, for example, Gerfred Mark (Gerda Marcus), ‘På vandring genom det dödsdömda Wien’, Svenska Dagbladet, 13 Feb. 1920; Gerda Marcus, ‘En tidsbild från Wien’, Jämtlandsposten, 31 Jan. 1921; Eugenie Schwarzwald, ‘Det svenska barnsanatoriet i Grimmenstein’, Gotlands Allehanda, 22 Feb. 1921.

36 Alice Trolle, ‘De små martyrerna’, Svenska Dagbladet, 23 Jan. 1920; for similar emotional reactions to witnessing, see ‘Ännu mer hjälp åt Wienbarnen är oundgänglig’, Dagens Nyheter, 16 Feb. 1920; E. Th., ‘Rädda Barnen! Samt livklädnaden och nästan’, Idun, 1 Feb. 1920; Elsa Björkman, ‘Bland dem som förgås i Wien’, Svenska Dagbladet, 2 Jan. 1921; Elin Wägner, ‘Den döende världsstaden’, Svenska Dagbladet, 24 Feb. 1921.

37 Regan, ‘Då Wien mottog Sveriges första hjälpsändningar’, Dagens Nyheter, 7 Jan. 1920.

38 Johan Jarlbrink, ‘Objektiv journalistik i bandspelarens tidevarv’, in Marie Cronqvist et al. (eds.), Mediehistoriska vändningar (Mediehistoriskt arkiv, 25; Lund: Lunds universitet, 2014), 47; Géraldine Muhlmann, A political history of journalism (Cambridge: Polity, 2008).

39 Elin Wägner, ‘Den döende världsstaden’, Svenska Dagbladet, 24 Feb. 1921; Alice Trolle, ‘De små martyrerna’, Svenska Dagbladet, 23 Jan. 1920.

40 Gerfred Mark (Gerda Marcus), ‘På vandring genom det dödsmärkta Wien’, Svenska Dagbladet, 13 Feb. 1920; Elsa Björkman, ‘Bland dem som förgås i Wien’, Svenska Dagbladet, 2 Jan. 1921; Elin Wägner, ‘Alla onda drömmars land’, Dagens Nyheter, 3 Feb. 1920; ‘Ännu mer hjälp åt Wienbarnen är oundgänglig’, Dagens Nyheter, 16 Jan. 1920; Gerda Marcus, ‘En tidsbild från Wien’, Jämtlandstidningen, 31 Jan. 1921.

41 Gerfred Mark (Gerda Marcus), ‘På vandring genom det dödsmärkta Wien’, Svenska Dagbladet, 13 Feb. 1920; Alice Trolle, ‘De små martyrerna’, Svenska Dagbladet, 23 Jan. 1920; ‘Skräcktillståndet i Budapest förvärras’, Svenska Dagbladet, 1 Mar. 1920; ‘Där köld och svält dagligen kräva offer’, Stockholms Dagblad, 7 Jan. 1920; ‘Där nöden och eländet råda’, Blekinge Läns Tidning, 29 Feb. 1921.

42 ‘Svältens följder för Wienbarnen’, Politiken, 29 Jan. 1920; ‘Nu 2,200 kr. åt Wienbarnen’, Bärgslags-Posten, 13 Dec. 1919; Elsa Björkman, ‘Bland dem som förgås i Wien’, Svenska Dagbladet, 2 Jan. 1921. My emphasis.

43 ‘Rädda Barnen!’, Falkenbergsposten, 29 Nov. 1920; Elin Wägner, ‘Den döende världsstaden’, Svenska Dagbladet, 24 Feb. 1921; ‘Hjälp! Hjälp! Hjälp!’, Alingsås Tidning, 15 Dec. 1920; Elin Wägner, ‘Ett utfattigt Centraleuropa en stor fara’, Dagens Nyheter, 20 Nov. 1920; ‘Svältens följder för Wien-barnen’, Politiken, 29 Jan. 1920.

44 ‘Vill du hjälpa en nödställd österrikisk familj?’, Södermanlands Läns Tidning, 21 Jan. 1920; cf. ‘Hjälp i nödens tid’ (Stockholm: Rädda Barnen, 1920).

45 ‘Rädda Barnens minneslista’, Afton-Tidningen, 30 July 1920, original emphasis. The RB’s list was published in several papers including Stockholms Dagblad (1 Aug. 1920) and Svenska Dagbladet (5 Aug. 1920).

46 ‘Nu 2,200 kr. åt Wienbarnen’, Bärgslagsposten, 13 Dec. 1919; cf. ‘Nöden i världen’, Upsala Nya Tidning, 27 Dec. 1920; Gurli Hertzman Ericson, ‘Från det hungrande Wien’, Afton-Tidningen, 7 Jan. 1920.

47 Fanny Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, ‘Det tigande landets nöd’, Stockholms Dagblad, 16 Feb. 1920, my emphasis.

48 See Qvarnström’s chapter in this volume.

49 Laqueur 1989; Rozario 2003, 421, 425–6.

50 Gurli Hertzman Ericson, ‘Från det hungrande Wien’, Afton-Tidningen, 7 Jan. 1920.

51 ‘Nöden i världen’, appeal from the International Save the Children Union, published for example in Upsala Nya Tidning, 27 Dec. 1920.

52 The reference is most likely to the Austrian branch of the Catholic Church charity Caritas (misspelt ‘Charitas’) in ‘Svältens följder för Wien-barnen’, Politiken, 29 Jan. 1920. Very few of the original press photographs have been found in the RB archives (RA, Förenings- och organisationsarkiv (73), Rädda Barnens riksförbund, Rädda Barnen 1985, Fotografier K1:2–6).

53 See, for example, Alice Trolle, ‘De små martyrerna’, Svenska Dagbladet, 23 Jan. 1920; Elsa Björkman, ‘Bland dem som förgås i Wien’, Svenska Dagbladet, 2 Jan. 1921; ‘Sverige—Hela världens lilla vän’, Veckojournalen, 29 Nov. 1920.

54 Fehrenbach 2015, 167, 176–82.

55 See, for example, Jörn Rüsen, ‘Holocaust, memory and identity building: Metahistorical considerations in the case of (West) Germany’, in Michael S. Roth & Charles G. Salas (eds.), Disturbing remains: Memory, history and crisis in the twentieth century (Los Angeles: Getty, 2001), 252–3; Jay Winter, Dreams of peace and freedom: Utopian moments in the twentieth century (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006a), 7–8.

56 ‘E. Th.’, ‘Rädda Barnen! Samt livklädnaden och nästan’, Idun, 1 Feb. 1920; Friederike Kind-Kovács 2016, 41, 57 discusses how Hungarian children’s deviating bodies were visualized as markers for how they differed from the nutritional norms and standards of the American Red Cross at the same time.

57 ‘Där nöden och eländet råda’, Blekinge Läns Tidning, 29 Feb. 1921; Gerda Marcus, ‘Bland dem som förgås i Wien’, Svenska Dagbladet, 2 Jan. 1921; Alice Trolle, ‘De små martyrerna’, Svenska Dagbladet, 23 Jan. 1920; Elin Wägner, ‘I förödmjukelsens dal’, Dagens Nyheter, 11 Jan. 1920.

58 Alice Trolle, ‘De små martyrerna’, Svenska Dagbladet, 23 Jan. 1920; Gerda Marcus, ‘Bland dem som förgås i Wien’, Svenska Dagbladet, 2 Jan. 1921.

59 Alice Trolle, ‘De små martyrerna’, Svenska Dagbladet, 23 Jan. 1920; ‘Nöden i Tyskland’, Stockholms Dagblad, 25 Jan. 1920; Elin Wägner, ‘I förödmjukelsens dal’, Dagens Nyheter, 11 Jan. 1920; ‘Där nöden och eländet råda’, Blekinge Läns Tidning, 29 Feb. 1921.

60 ‘Livets igenstoppade källa’, Tranås Tidning, 5 Mar. 1921, a report that is unsigned, but almost an exact reprint of Elin Wägner, ‘Den döende världsstaden’, Svenska Dagbladet, 24 Feb. 1921; cf. Eugenie Schwarzwald, ‘Gåvor från Fru Liljecronas hem’, Upsala Nya Tidning, 30 Mar. 1920.

61 ‘Tusen sinom tusen barn förgås ännu af hunger’, Nya Dagligt Allehanda, 18 Dec. 1920; cf. ‘För mycket för att dö, men för litet för att leva’, Svenska Dagbladet, 12 Jan. 1921; ‘Wienbarnens svenska mamma på besök’, Stockholms-Tidningen, 11 Jan. 1921.

62 Jay Winter, Remembering war: The Great War between memory and history in the twentieth century (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006b), 55.

63 ‘Rädda Barnen!’, appeal for Save the Children, published for example in Falkenbergsposten, 29 Nov. 1920.

64 Winter 2006b, 60–1, 75.

65 Fehrenbach 2015, 167, 176–7; Barnett 2011, 85–6; Irwin 2013, 88, 167–81; Cabanes 2014, 248–99; Kind-Kovács 2016, 39; Dominique Marshall, ‘The construction of children as an object of international relations: The Declaration of Children’s Rights and the Child Welfare Committee of the League of Nations, 1900–1924’, International Journal of Children’s Rights, 7 (1999), 103–147.

66 Sturfelt 2008, 175–7.

67 Barnett 2011, 27–28, 227 discusses the ‘transcendental’ aspects of post-war humanitarianism, claiming that it helped the survivors ‘to come to terms with their ghosts’ by turning communities of memory and mourning into moral communities (and institutions) of care; cf. Bergström’s chapter in this volume.

68 Fehrenbach 2015, 179.

69 ‘Vad Rädda Barnen gör av en 25-öring’, Idun, 21 Nov. 1920.

70 Linda Mahood & Vic Satzewich, ‘The Save the Children Fund and the Russian famine of 1921–23: Claims and counter-claims about feeding “Bolshevik” children’, Journal of Historical Sociology, 22/1 (2009), 63.

71 Jay Winter, Sites of memory, sites of mourning: The Great War in European cultural history (Cambridge: CUP, 1995).

72 Aubrey Graham, ‘One hundred years of suffering? “Humanitarian crisis photography” and self-representation in the Democratic Republic of Congo’, Social Dynamics, 40/1 (2014), 153.

73 ‘Svältens följder för Wien-barnen’, Politiken, 29 Jan. 1920; Gerda Marcus, ‘En tidsbild från Wien’, Jämtlandsposten, 31 Jan. 1921.

74 ‘Där nöden och eländet råda’, Blekinge Läns Tidning, 29 Feb. 1921; see also Gerfred Mark (Gerda Marcus), ‘På vandring genom det dödsmärkta Wien’, Svenska Dagbladet, 13 Feb. 1920; Alice Trolle, ‘De små martyrerna’, Svenska Dagbladet, 23 Jan. 1920; ‘Nöden i Tyskland’, Stockholms Dagblad, 25 Jan. 1920.

75 Graham 2014, 141–6, 149, 157.

76 Ibid. 146; cf. Fehrenbach & Rodogno 2015, 6.

77 Gerfred Mark (Gerda Marcus), ‘På vandring genom det dödsmärkta Wien’, Svenska Dagbladet, 13 Feb. 1920; for photographs similar to that of the boy, see ‘Svältens följder för Wien-barnen’, Politiken, 29 Jan. 1920; Anna Lenah Elgström, ‘Den dömda stadens döende barn’ (Stockholm: Rädda Barnen, 1919).

78 Twomey 2012, 259; Laqueur 1989, 179; for war stories become flesh, see Winter 2006b, 57.

79 Miggs, ‘Ett slag för de slagna’, Veckojournalen, 16 May 1920.

80 Sliwinski 2006, 335; cf. Twomey 2012, 255, 258, 263.

81 Fehrenbach 2015, 176; Graham 2014, 147.

82 ‘Sverige—Hela världens lilla vän’, Veckojournalen, 29 Nov. 1920; ‘De namnlösa barnen i Wiens baracker vädja till vårt medlidande’, Svenska Dagbladet, 5 Mar. 1920; cf. Elsa Björkman, ‘Bland dem som förgås i Wien’, Svenska Dagbladet, 2 Jan. 1921; ‘Vad Rädda Barnen gör av en 25-öring’, Idun, 21 Nov. 1920.

83 Graham 2014, 153.

84 According to Kind-Kovács 2016, 45, the ways in which interwar humanitarians accessed and regulated the impaired and powerless child’s body was also ‘an invasion into the children’s most intimate lives’.

85 Hannah Arendt, On revolution (London: Penguin Books, 2006), 78f.

86 Fehrenbach & Rodogno 2015, 6.

87 Marshall 1999; Dominique Marshall, ‘Children’s rights and children’s actions in international relief and domestic welfare: The work of Herbert Hoover between 1914 and 1950’, Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth 1/3 (2008), 351–88; Dominique Marshall, ‘Humanitarian sympathy for children and the history of children’s rights, 1919–1959’, in Marten 2002, 184–200; Lara Bolzman, ‘The advent of child rights on the international scene and the role of the Save the Children International Union 1920–45’, Refugee Survey Quarterly, 27/4 (2009), 26–36; Cabanes 2014, 289–99; see also the Geneva Declaration of the Rights of the Child, http://www.un-documents.net/gdrc1924.htm. (accessed 20 Dec. 2017).

88 Kind-Kovács 2016, 40.

89 Cabanes 2014, 309.

90 In order, Elsa Björkman, ‘Bland dem som förgås i Wien’, Svenska Dagbladet, 2 Jan. 1921; ‘Hjälp! Hjälp! Hjälp!’, Alingsås Tidning, 15 Dec. 1920; ‘Det tigande landets nöd’, Stockholms-Tidningen, 16 Feb. 1920; Alice Trolle, ‘De små martyrerna’, Svenska Dagbladet, 23 Jan. 1920; and Björkman again.

91 ‘Mer hjälp till Wienbarnen nödvändig’, Dagens Nyheter, 16 Jan. 1920; ‘Hopplösa bilder från det svältande Wien’, Svenska Dagbladet, 15 Jan. 1920; cf. ‘Svältens följder för Wien-barnen’, Politiken, 29 Jan. 1920; ‘Tusen sinom tusen barn förgås ännu af hunger’, Nya Dagligt Allehanda, 18 Dec. 1920; Elin Wägner, ‘I förödmjukelsens dal’, Dagens Nyheter, 11 Jan. 1920; ‘Rädda Barnen!’, Falkenbergsposten, 29 Nov. 1920; Elin Wägner, ‘Den döende världsstaden’, Svenska Dagbladet, 24 Feb. 1921; ‘Rädda Barnens minneslista’, Afton-Tidningen, 30 July 1920.

92 Cabanes 2014, 220–2, 260–1, 288; Mahood & Satzewich 2009, 63–4; Salvatici 2015, 210–11; Fehrenbach 2015, 177, 179, 181; Rozario 2003, 419, 430–2; Irwin 2013, 87; Francesca Piana, ‘Photography, cinema and the quest for influence: The International Committee of the Red Cross in the wake of the First World War’, in Fehrenbach & Rodogno 2015, 152, 156–8; Fehrenbach & Rodogno 2015, 11. In neutral Scandinavia, the war was also a turning point in the visual mediation of war and for photojournalism. Accurate and authentic war pictures became a matter of fierce competition and keen marketing practices. There was a widespread notion that the visual mediation especially brought the war’s suffering closer to the neutrals; see Ulrik Lehrmann, ‘An album of war: The visual representation of the First World War in Danish magazines and daily newspapers’, in Claes Ahlund (ed.), Scandinavia in the First World War: Studies in the war experience of the Northern neutrals (Lund: Nordic Academic Press, 2012), 57–84; Sturfelt 2008, 37–43; Jarlbrink 2009, 181–4; Rohdin 2015.

93 It is notable that during the war years Swedish illustrated magazines, otherwise rich in horrifying images of death and destruction, including human remains, explicitly refrained from publishing pictures of dead or maimed civilians, especially women and children (Sturfelt 2008, 139–83, especially 155).

94 Rozario 2003, 443.

95 See Kärrholm’s chapter in this volume.

96 Laura Sjoberg, Gender, war and conflict (Cambridge: Polity, 2014), 113, 123, 133, 156, 164, 167; see also Laura Sjoberg, Gendering global conflict: Toward a feminist theory of war (New York: Columbia University Press, 2013); Sylvester 2013; Nicholas J. Saunders & Paul Cornish (eds.), Modern conflict and the senses (Abingdon: Routledge, 2017); and Skoog’s chapter in this volume.

97 ‘Hjälp! Hjälp! Hjälp!’, Alingsås Tidning, 15 Dec. 1920.

98 Winter 2006b, 6, 76; cf. Little 2015, 13; Cabanes 2014, 4, 301, 307 for the blurred boundaries between war and peace in the transition period.

References

Archival sources

Riksarkiven (Swedish National Archives) (RA), Stockholm

Förenings- och organisationsarkiv (73), Rädda Barnens riksförbund, Rädda Barnen 1985, Samlingsserie övriga handlingar F1f:2, 1920–50-tal, diverse trycksaker.

RA, Förenings- och organisationsarkiv (73), Rädda Barnens riksförbund, Rädda Barnen 1985, Samlingsserie övriga handlingar F1f:1, 1920–1949, Medlemstidning 1920–26.

RA, Förenings- och organisationsarkiv (73), Rädda Barnens riksförbund, Rädda Barnen 2005, Styrelsen A2:1, 1920–1922, Kartong (protokoll styrelsesammanträden).

RA, Förenings- och organisationsarkiv (73), Rädda Barnens riksförbund, Rädda Barnen 2005, Övrigt Pressklipp Ö1, 1–6, 1919–1923.

Secondary sources

Arendt, Hannah, On revolution (London: Penguin Books, 2006) (first pub. 1963).

Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane & Annette Becker, 14–18: Understanding the Great War (New York: Hill and Wang, 2003).

Barnett, Michael, Empire of humanity: A history of humanitarianism (New York: Ithaca, 2011).

Bass, Gary J., Freedom’s battle: The origins of humanitarian intervention (New York: Knopf, 2008).

Baughan, Emily, ‘Every citizen of empire implored to Save the Children! Empire, internationalism and Save the Children in interwar Britain’, Historical Research, 86/231 (2013), 116–37.

Björkman-Goldschmidt, Elsa, ‘Så var det i Wien’, in Vera Forsberg, Att rädda barn: En krönika om Rädda Barnen med anledning av dess femtioåriga tillvaro (Stockholm: Rädda Barnen, 1969), 117–21.

Boltanski, Luc, Distant suffering: Morality, media and politics, tr. Graham D. Burchell (Cambridge: CUP, 1999).

Bolzman, Lara, ‘The advent of child rights on the international scene and the role of the Save the Children International Union 1920–45’, Refugee Survey Quarterly, 27/4 (2009), 26–36.

Bourke, Joanna, Dismembering the male: Men’s bodies, Britain and the Great War (London: Reaktion, 1996).

Cabanes, Bruno, The Great War and the origins of humanitarianism, 1918–1924 (Cambridge: CUP, 2014).

Carden-Coyne, Ana, ‘Gendering the politics of war wounds since 1914’, in Ana Carden Coyne (ed.), Gender and conflict since 1914 (Houndsmill: Palgrave Mac-Millan, 2012).

Chouliaraki, Lilie, ‘Afterword: The dialectics of mediation in “distant suffering studies”’, International Communication Gazette, 77/7 (2015), 708–14.

Fehrenbach, Heide & Davide Rodogno (eds.), Humanitarian photography: A history (Cambridge: CUP, 2015).

—— —— ‘Introduction: The morality of sight: Humanitarian photography in history’, in Fehrenbach & Rodogno 2015, 1–21.

—— ‘Children and other civilians: Photography and the politics of humanitarian image-making’, in Fehrenbach & Rodogno 2015, 165–199.

Forsberg, Vera, Att rädda barn: En krönika om Rädda Barnen med anledning av dess femtioåriga tillvaro (Stockholm: Rädda Barnen, 1969).

Geneva Declaration of the Rights of the Child, http://www.un-documents.net/gdrc1924.htm (accessed 20 Dec. 2017).

Graham, Aubrey, ‘One hundred years of suffering? “Humanitarian crisis photography” and self-representation in the Democratic Republic of Congo’, Social Dynamics, 40/1 (2014), 140–163.

Hällgren, Anna-Maria, Skåda all världens uselhet: Visuell pedagogik och reformism i det sena 1800-talets populärkultur (diss.; Möklinta: Gidlunds, 2013).

Hitchcock, William I., ‘World War I and the humanitarian impulse’, Tocqueville Review/La revue Tocqueville, 35/2 (2014), 145–63.

Hoffmann, Stefan Ludwig, ‘Gazing at ruins: German defeat as visual experience’, Journal of Modern European History, 9 (2011), 328–50.

Irwin, Julia, Making the world safe: The American Red Cross and a nation’s humanitarian awakening (Oxford: OUP, 2013).

Janfelt, Monika, ‘Svensk krigsbarnsverksamhet 1919–1922’, Historisk tidskrift för Finland, 75 (1990), 465–98.

—— Stormakter i människokärlek: Svensk och dansk krigsbarnshjälp 1917–1924 (diss.; Åbo: Åbo akademi, 1998).

Jarbrink, Johan, Det våras för journalisten: Symboler och handlingsmönster för den svenska pressens medarbetare från 1870-tal till 1930-tal (diss.; Mediehistoriskt arkiv, 11; Stockholm: Kungliga biblioteket, 2009).

—— ‘Objektiv journalistik i bandspelarens tidevarv’, in Marie Cronqvist, Johan Jarlbrink & Patrik Lundell (eds.), Mediehistoriska vändningar (Mediehistoriskt arkiv, 25; Lund: Lunds universitet, 2014), 43–66.

Kind-Kovács, Friederike, ‘The “other” child transports: World War I and the temporary displacement of needy children from Central Europe’, Revue d’histoire de l’enfance ‘irrégulière’, 15 (2013), 75–109.

—— ‘The Great War, the child’s body and the American Red Cross’, European Review of History/Revue Européenne d’Histoire, 23/1–2 (2016), 33–62.

Kramer, Alan, Dynamic of destruction: Culture and mass killing in the First World War (Oxford: OUP, 2007).

Laqueur, Thomas W., ‘Bodies, details and the humanitarian narrative’, in Lynn Hunt (ed.), The new cultural history (Berkeley & Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1989), 176–204.

—— ‘Mourning, pity, and the work of narrative in the making of humanity’ in Richard Ashby Wilson & Richard D. Brown (eds.), Humanitarianism and suffering: The mobilization of empathy (Cambridge: CUP, 2009), 31–57.

Lehrmann, Ulrik, ‘An album of war: The visual representation of the First World War in Danish magazines and daily newspapers’, in Claes Ahlund (ed.), Scandinavia in the First World War: Studies in the war experience of the Northern neutrals (Lund: Nordic Academic Press, 2012), 57–84.

Little, Branden, ‘Humanitarian relief and the analogue of war’, in Jennifer D. Keene & Michael S. Neiberg (eds.), Finding common ground: New directions in First World War Studies (Leiden: Brill, 2011), 75–101.

—— ‘An explosion of new endeavours: Global humanitarian responses to industrial warfare in the First World War era’, First World War Studies, 5/1 (2015), 1–16.

Mahood, Linda & Vic Satzewich, ‘The Save the Children Fund and the Russian famine of 1921–23: Claims and counter-claims about feeding “Bolshevik” children’, Journal of Historical Sociology, 22/1 (2009), 55–83.

—— Feminism and voluntary action: Eglantyne Jebb and Save the Children 1876–1928 (London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2009).

Marshall, Dominique, ‘The construction of children as an object of international relations: The Declaration of Children’s Rights and the Child Welfare Committee of the League of Nations, 1900–1924’, International Journal of Children’s Rights, 7 (1999), 103–147.

—— ‘Humanitarian sympathy for children and the history of children’s rights, 1919–1959’, in James Marten (ed.), Children and war: A historical anthology (New York: NYUP, 2002), 184–200.

—— ‘Children’s rights and children’s actions in international relief and domestic welfare: The work of Herbert Hoover between 1914 and 1950’, Journal of the History of Childhood & Youth, 1/3 (2008), 351–88.

Marten, James (ed.), Children and war: A historical anthology (New York: NYUP, 2002).

McSorley, Kevin (ed.), War and the body: Militarisation, practice and experience (London: Routledge, 2013).

Minnesskrift över föreningen Rädda Barnens 20-åriga verksamhet i Sverige, 1919–1939 (Stockholm: Rädda Barnen, 1939).

Muhlmann, Géraldine, A political history of journalism, tr. Jean Birrell (Cambridge: Polity, 2008).

Mulley, Clare, The woman who saved the children: A biography of Eglantyne Jebb, founder of Save the Children (Oxford: Oneworld, 2009).

Nehlin, Ann, Exporting visions and saving children: The Swedish Save the Children Fund (diss.; Linköping: Department of Child Studies, 2009).

Orgad, Shani & Irene Bruna Seu, ‘The mediation of humanitarianism: Toward a research framework’, Communication, Culture & Critique, 7 (2014), 6–36.

Piana, Francesca, ‘Photography, cinema and the quest for influence: The International Committee of the Red Cross in the wake of the First World War’, in Fehrenbach & Rodogno 2015, 140–164.

Qvarnström, Sofi, Motståndets berättelser: Elin Wägner, Anna Lenah Elgström, Marika Stiernstedt och första världskriget (diss.; Möklinta: Gidlund, 2009).

Rodogno, Davide, Against massacre: Humanitarian intervention in the Ottoman Empire 1815–1914 (Princeton: PUP, 2012).

Rohdin, Mats, ‘När kriget kom till Sverige: Första världskriget på bioduken’, Biblis, 68 (2015), 2–19.

Rozario, Kevin, ‘“Delicious horrors”: Mass culture, the Red Cross, and the appeal of modern American humanitarianism’, American Quarterly, 55/3 (2003), 417–455.

Rüsen, Jörn, ‘Holocaust, memory and identity building: Metahistorical considerations in the case of (West) Germany’, in Michael S. Roth & Charles G. Salas (eds.), Disturbing remains: Memory, history and crisis in the twentieth century (Los Angeles: Getty, 2001), 252–270.

Salvatici, Silvia, ‘Sights of benevolence: UNRRA’s recipients portrayed’, in Fehrenbach & Rodogno 2015, 200–222.

Saunders, Nicholas J. & Paul Cornish (eds.), Bodies in conflict: corporeality, materiality, and transformation (New York: Routledge, 2014).

—— —— (eds.), Modern conflict and the senses (Abingdon: Routledge, 2017).

Simms, Brendan & D. J. B. Trim, Humanitarian intervention: A history (Cambridge: CUP, 2011).

Sjoberg, Laura, Gendering global conflict: Toward a feminist theory of war (New York: Columbia University Press, 2013).

—— Gender, war and conflict (Cambridge: Polity, 2014).

Sliwinski, Sharon, ‘The childhood of human rights: The Kodak on the Congo’, Journal of Visual Culture, 5/3 (2006), 333–363.