CHAPTER 7

Framing the waste of war

Motifs, paratexts, and other framing devices in EC’s Cold War comics

The period immediately after the Second World War has been described as one of the most difficult times to express messages that in any way deviated from the norms of containment culture. The publication of the Comics Code by the Comics Magazine Association of America (CMAA) saw the introduction of censorship to that particular form of popular entertainment.1 The publishing house EC Comics, under its editor-in-chief Bill Gaines, was among the comic producers who received most attention in the debate about the potentially harmful effects of comics on young readers, thanks to their list of horror titles such as Tales from the Crypt and Shock Suspensestories. EC also published war comics that could be seen as controversial for other reasons. The visualization and narrative depictions of war were in these stories designed to shock the reader in a similar way to the effects of the horror books. They aimed to show the gruesome side of war, but also to provoke thoughts of a more philosophical kind about war and its effects on the human body and soul. This was done using a range of recurring motifs, but also different framing devices.

The Second World War was a golden age for comic book sales. This was due to a growing readership of adolescents with money to buy their own comic books without the mediation of their parents, but also to a vast audience of soldiers consuming comic books while at war.2 According to the historian Jean-Paul Gabillet, comic books ‘maintained the morale of troops stationed in foreign countries, participated in the anti-fascist propaganda on the home front, and satisfied the demand for entertainment from an audience that had more money to spend at a time when the possibility of purchasing consumer goods was severely restricted by the constraints of the war effort’.3 Comic books thus had an important function for readers who were fighting or otherwise engaged in the war, providing strategies to cope with their experiences by enforcing certain values. In this context, it is interesting that EC managed to express a very different and subversive image of combat in their own war magazines: Two-Fisted Tales and Frontline Combat.4

The aim of this chapter is to chart the media-specific factors that determined how certain subversive messages might be communicated. The first part of the chapter will show how EC used a specific motif—the dead body—and its framing in the layout of the comic, to convey an anti-war message. The second part of the chapter will demonstrate how that same message was enforced by the different paratexts associated with the comics in the magazines. Form and content were made to work together to draw readers into a dialogue about the meaning of war and to provide the right framing for their interpretation specifically of the Korean War (1950–1953), but also for recent experiences of the Second World War.

For this chapter, the reprinted issues of Two-Fisted Tales in the EC Archives series are used as primary sources. This means that the comics discussed are in a sense lifted into a new context, one that has the ambition to consolidate EC’s production and uphold its legacy—indeed, I end the chapter with a reflection on this situation and what it means for the analysis. In the reprints, the original issues are reproduced in chronological order, assembling six dated issues in each volume. The issues are printed as facsimiles up to a point, but extra material is dispersed between them, adding a commentary function as well as providing a historical context for the individual issues and EC’s work as a whole.5 The analysis in this chapter, then, is not based on an entirely historically accurate material, but one that brings the issues of history and memory, connected to a printed medium, to the fore.

Two-Fisted Tales and Frontline Combat were the two of EC’s publications to feature war stories. Besides the importance of Bill Gaines as decision maker, the artist Harvey Kurtzman had a central role in the making of the stories. He ‘researched, wrote, edited, and provided complete visual breakdowns for all of the war stories’, with the support of several other artists.6 The stories were a mix of recent events in the Korean War or Second World War, and others inspired by wars further back, such as the American War of Independence. Most of the stories describe the hopelessness of war, making the point that there really are no winners, and that all men are equal in its path, as is claimed by the narrative voice in the story ‘Hill 203!’: ‘death treats all men equally and makes no distinction between Chinese and Americans’.7

The outbreak of the Korean War in June 1950 was the immediate reason that EC started to publish their war comics, and the end of the war in 1953 similarly spelt the end for these publications.8 After that, EC instead chose to concentrate on their humorous titles: MAD and Panic.9 The war publications were thus created and sold for a short timespan of two years, directly connected to the war in Korea, while the experiences from the Second World War were still a very fresh memory.

Against this background, it is interesting to see EC’s war comics as a medium that was used to comment not only on a war that was ongoing at the time of their publication (and to motivate combatants), but also on the recent Second World War, and to express a post-war experience. According to Leonard Rifas, the Korean War years were a ‘peak period for US comic book sales and impact (but not respect)’. He shows that the norm at the time was to glorify war and describe the enemy in generalizing terms, which was in great contrast to how this particular war and its enemies were described in EC’s war comics.10

Paratexts and frames

Part of the analysis will concern what the literary theorist Gérard Genette has defined as paratexts. Genette describes paratexts as ‘thresholds of interpretation’, and uses them mainly with literary texts.11 They consist of the elements surrounding the narrative text, and are used to guide the reader’s understanding when it comes to providing information about, for example, genre and author. Genette furthermore divides the paratext into peritext and epitext. Peritexts exist in the immediate context of the literary work, such as the jacket, title page, footnotes, illustrations, et cetera. Epitexts are more peripheral and not as easily defined, but could consist of other material that could be assigned as the author’s or the publisher’s intentions, such as marketing texts in catalogues and interviews with the author.12 In a sense, then, these paratexts serve to direct the reader’s attention towards certain things inside as well as outside the text. In this context, it is of interest to study the peritexts, or immediate surroundings of the war narratives—all the other elements that were included in the comic books and that could be read alongside the comics.

The literary scholar Marie Maclean has developed Genette’s terminology, discussing the way paratexts work as frames, ‘what relates a text to its context’, and the different ways this can function:

The frame may act as a means of leading the eye into the picture, and the reader into the text, thus presenting itself as the key to a solipsistic world; or it may deliberately lead the eye out, and encourage the reader to concentrate on the context rather than the text. Sometimes indeed the frame defines the text, by appropriateness or complementarity; at others it defines the context, like an elaborately carved art nouveau setting to a simple mirror.13

The paratextual frame thus contextualizes, but is not to be conflated with, the context per se, since it is the means by which the reader is directed towards the text and context.

The frame as a concept is also central to frame analysis, coined by sociologist Erving Goffman (1986), and used to discuss how frames are used to provide meaningful structures for the individual interpreter of any scene or social interaction.14 Media theorists have used this to model how the media can provide mediated events with frames in order to evoke certain meanings for the media consumer.15 According to this theory, both consumers and producers use frames in order to make meaning out of the message. The frames provided by the producer act to direct the consumer’s attention to a certain symbolic field, for instance, while the consumer also brings to the situation the frames that he or she has developed in earlier and similar situations.16

In comic books, frames are used to talk about the spatial dimensions of the medium: how frames are placed on the page or the two-page spread. Lefèvre defines it thus: ‘Framing in comics refers both to the choice of a perspective on a scene, and to the choice of borders of the image.’17 As the literary scholar Hillary Chute has pointed out, comics are of special interest to discuss in relation to framing, since ‘while all media do the work of framing, comics manifest material frames—and the absences between them. It thereby literalizes on the page the work of framing and making, and also what framing excludes.’18

The comic theorist Thierry Groensteen uses the concepts of frame, hyperframe, and multiframe. The frame is used for the immediate frame of a single frame in a comic. The hyperframe is the frame consisting of each page in a comic—how the placing of the frames are assigned a certain space on the page, framed by the (often white) outer margins, not counting the white spaces within the margins. The multiframe, in turn, can take on varying forms and consist of less than a page—in the comic strip—a half page, and also the whole comic book or magazine. It is a frame comprising one or more comic narratives.19 When discussing the different elements of the comic books, different peritexts, I will be commenting on the multiframe of the war comics, while the hyperframe and frame, in Groensteen’s sense, may become interesting while analysing the stories themselves. For this chapter, however, the meaning of the frame will also be used as a paratext function, when analysing for instance bulletin boards, book jackets, and advertisements, and how they relate to the stories about the waste of war.

Dead bodies everywhere!

One of the most frequently analysed functions in comics is the media-specific uses of temporality. The reader has to actively participate in creating and interpreting temporal movement from a succession of still frames or panels.20 Another important and media-specific aspect of comics is the function of the parts to the whole. The whole page is always present to the reader—and so is normally the counter-page in a two-page layout—when reading single frames. The page as a whole thus becomes a primary context for the interpretation of each frame. This makes spatial dimensions integral to the medium in a different way than in, say, film.21 The gutter, the space in between the frames, can be seen to have a decisive function in this regard, since it serves to ‘divide and proliferate time’ in comics.22 Spatial concerns and how they affect the temporal in EC’s war stories will be addressed in the following.

Death as a consequence of war is naturally present in most if not all of the stories in both Two-Fisted Tales and Frontline Combat. In two of the stories commented upon here, a dead body is used as both the starting and finishing point. This kind of circular movement, where a scene is repeated with variations in the first and last frame, was a narrative device that was used repeatedly in EC’s war comics in interesting ways. It can be seen in the story ‘Bug out!’, where the same words, with a slight variation, are repeated at the beginning and the end of the story. In this case, the repeated movement back to the beginning serves as an interesting way to describe the disturbed mind-set of a war veteran suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, who is unable to let his mind go of the events of one catastrophic day of war.23 Another version is in ‘Lost battalion!’, where the narrative at the outset is told from the perspective of a man lying on the ground with his rifle. At the end of the story the man is still lying there with the same facial expression, and turns out to be dead, but still narrates: ‘The boys will go back but I’ll stay here… covered with branches and why not… I’m dead!’24 Many of the stories use this circular movement with dead bodies serving as the starting and the end points, which serves to emphasize the waste of war.25 I will specifically look at the function of the dead in ‘Search!’ (1951), ‘Hill 203!’ (1951), and ‘Corpse on the Imjin!’ (1952).26

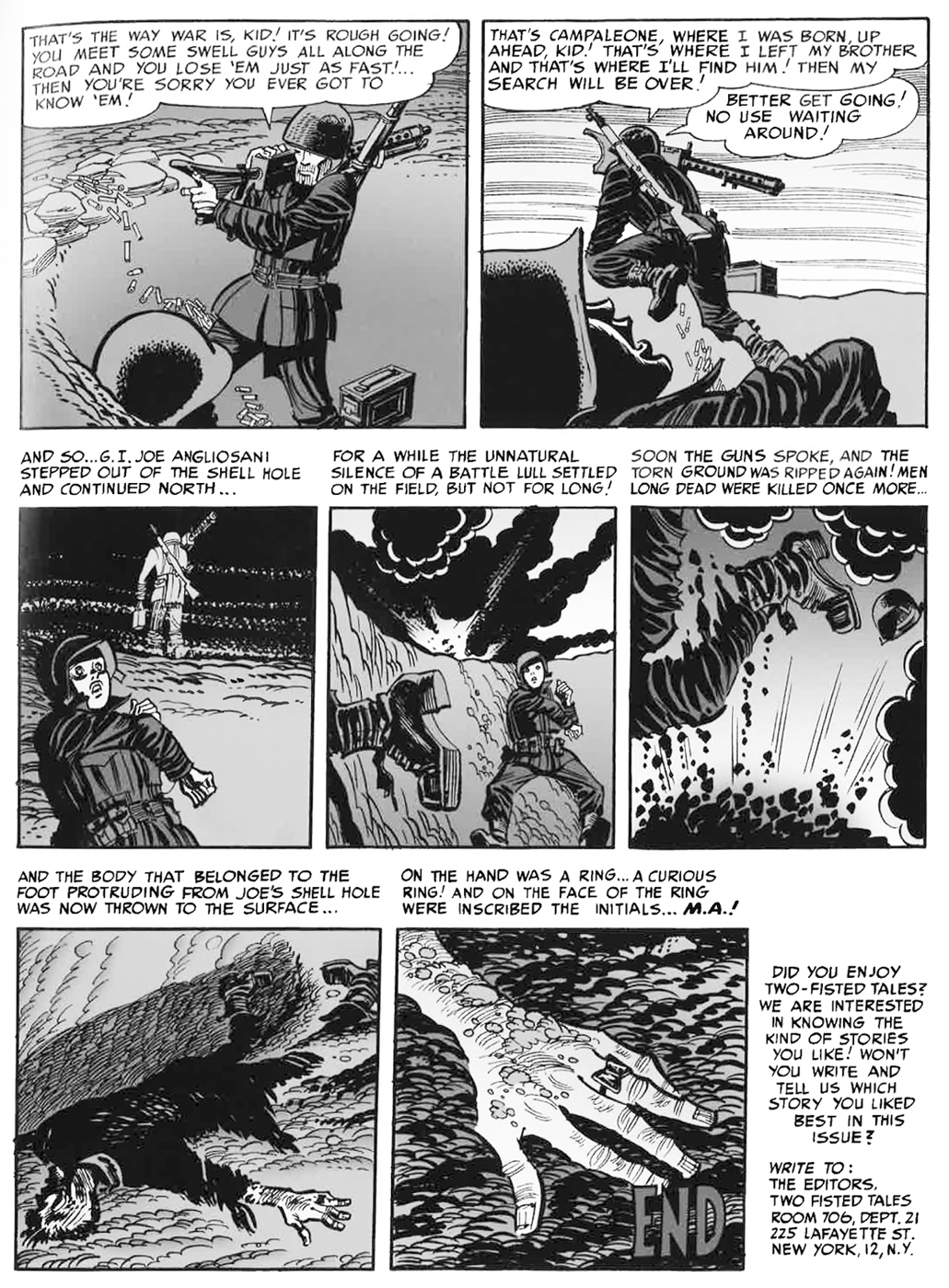

The story ‘Search!’ describes the meeting of a young American soldier with a senior American soldier of Italian descent in a bomb crater in Salerno, Italy, in 1943. The older soldier, Joe, has already been posted there for a long time when the newcomer arrives, and he tells the boy a story that explains why he has chosen to stay on in Italy. His older brother Mario, the sole survivor of his family beside himself, was left behind in Italy when Joe was sent to America. Joe now wants to reunite with him before returning home. He made sure he was picked to serve in the 45th Division, where he would have a chance to search for his brother.

The images underline the contrast in age and experience between the two men. This meeting between generations on the battlefield, where the older man passes on his wisdom to the younger, is another device that was used repeatedly in EC’s war comics.27 In ‘Search!’, Joe is described as a tough character, his face black with dirt and with a grim look on it. The boy is portrayed throughout with the same facial expression, one that reflects his fear and inexperience: his eyes as well as his mouth are drawn round and wide open.

During their conversation the boy points in shock at the foot of a dead body, sticking up out of the side of the shell hole. Joe tells him to calm down: ‘It’s only the foot of a corpse buried in the rubble! You get used to them after a while!’ The conversation is suddenly interrupted by an attack, and after silencing the assailants, Joe can continue his story about his brother. He claims that after all the time that has passed since he last saw him, he will still be able to recognize him from the ring on his finger, engraved with his initials, M. A. Joe wears one himself, with his own initials. Another attack interrupts him and when Joe turns around afterwards, it is to find the boy killed, still with the same blank expression on his face.

The dead state of the boy’s body is accentuated in the images through a sequence of pictures of his stiff body, locked into an uncomfortable position, and with that blank, staring look in his eyes. Right through a sequence of six frames, Joe continues to talk to the dead body as if he was still there. He then decides to leave the shell hole in order to continue his search for his brother. The perspective, as he walks away, remains on the dead body in the crater, along with the foot still sticking out from the rubble. We follow the dead bodies through another attack, while the narrative voice says: ‘Soon the guns spoke, and the torn ground was ripped again! Men long dead were killed once more’. The whole body of the man with the foot is thrown to the surface and the story ends with a close-up of his hand, a deathly grey colour, with a ring on its finger with the initials M. A. What was before an anonymous, lifeless foot is now a whole and visible body with a specific identity.

The narrative in a powerful way contrasts the anonymity of death and war with the specific and personal narrative of Joe Angliosani, the man in search of his brother and a way to find closure in the long-awaited reunion with what remains of his family. His very personal reasons for being in that place at that time are paralleled with the situation that makes him, his fellow soldier who is sharing a moment with him in the crater, and the dead body of his brother into anonymous nobodies. His exertions to hold on to his personal history are futile in the face of the horrors of war. Apart from the fact that we never learn the name of the boy (only ever called ‘Kid’ by Joe) and that the foot at first is described as just another dead body, anonymity is evoked again when Joe Angliosani—a man who we do know by name—is called ‘GI Joe Angliosani’ by the narrator, when he steps out of the shell hole and walks away at the end of the story. He still has his name, but the first part of it is just the anonymous name used for any American soldier.

‘Search!’, page 2. Art by Harvey Kurtzman. Copyright © 1951, William M. Gaines, Agent, Inc. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.

‘Search!’, page 7. Art by Harvey Kurtzman. Copyright © 1951, William M. Gaines, Agent, Inc. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.

In contrast, the dead bodies are in some sense treated as more than faceless bodies. Despite the lack of name and facial characteristics, the boy is talked to after his death as if he was still alive and listening. His function as an attentive listener lives on for as long as Joe needs it. This is accentuated by the presence of his stiff body in a sequence of nine consecutive frames. The final four frames show only dead bodies, first the body of the boy together with the foot of the corpse in the rubble, and then the corpse in the strange process of being ‘killed once more’ and thus brought to the surface. The corpse of what the reader will eventually learn is Joe’s brother regains his lost identity at the end because of the signet ring, making Joe’s earlier comment that he was just another dead body ironic.

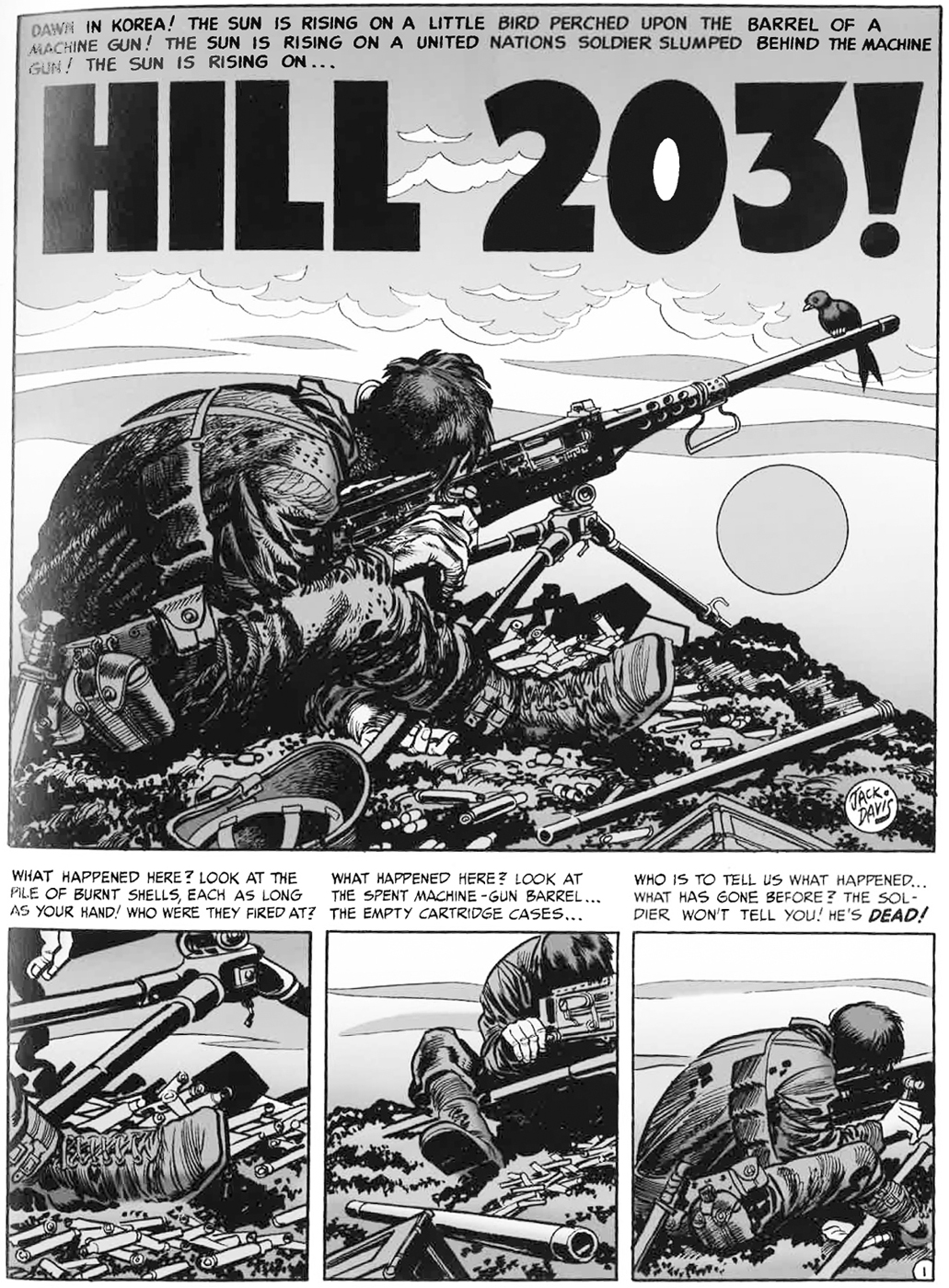

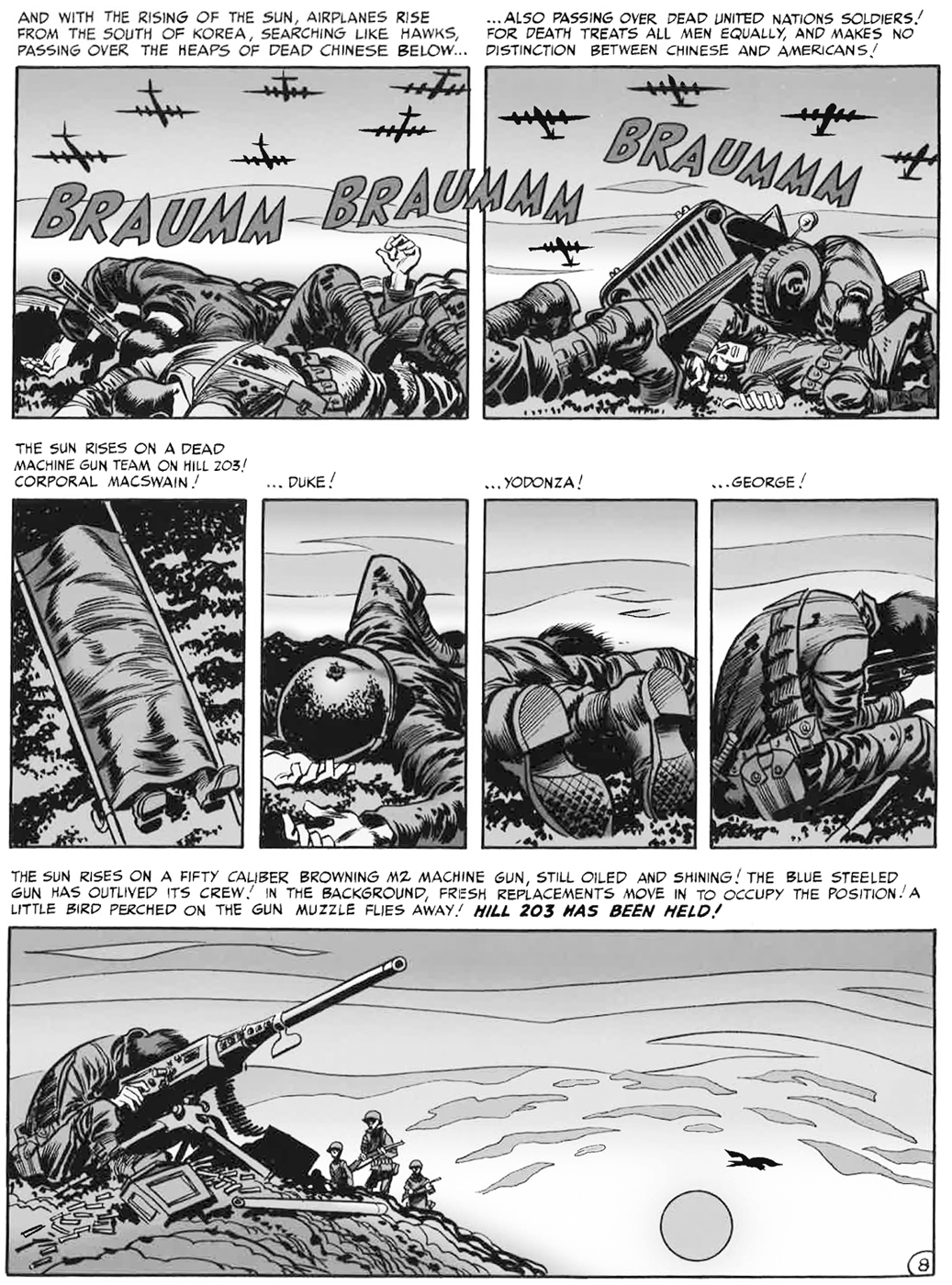

Another story, ‘Hill 203!’, starts with a company of UN soldiers getting a machine gun rigged to defend a hill. It is a ‘fifty-calibre air-cooled machine gun, a light tripod, and four cans of ammo’, a weapon that so fascinates one of the younger soldiers that he wishes to take some of its oversized ammo as a keepsake to take home. The gun requires one man pulling the retracting handle and one man feeding the gun with the ammo belt. A confrontation between the soldiers and their Korean enemies is set off, and the men handling the machine gun have the main function of holding ground until help arrives. Before that can happen, three men are killed one after another while manning the gun, among many others killed on both sides, so that when help finally arrives all the soldiers holding the hill are dead, as well as all the Korean soldiers attacking them.

The opening frame as well as the very last shows George’s corpse, the last man to use the gun. His image thus becomes, in a way, the framing of the story. The scenery is a beautiful sunrise, and a little bird is perched on the barrel in the first frame and flies away in the last one. The scene is highlighted as if a strange pause in the killing. At the outset everything is quiet and still, as if the narrator had somehow paused the image in order to philosophically take a moment to investigate: ‘What happened here? Look at the pile of burnt shells, each as long as your hand! Who were they fired at? [Frame 2] What happened here? Look at the spent machine-gun barrel… the empty cartridge cases… [Frame 3] Who is to tell us what happened… what has gone before? The soldier won’t tell you! He’s dead!’28

The pictures highlight the gun and its grotesque dimensions, the littering of empty cases, and the unnatural pose of the soldier’s dead body, which seems to be resting on the gun, ready to shoot. At the end of the story this scene is recalled, but only after showing the piles of dead bodies around the soldier, while the rescuing planes sweep in. The last five frames show the dead bodies of Corporal MacSwain, Duke, Yodonza, and George—all soldiers who held off the attackers with the machine gun. The story ends with the gun: ‘The sun rises on a fifty calibre Browning M2 machine gun, still oiled and shining! The blue steeled gun has outlived its crew! In the background, fresh replacements move in to occupy the position! A little bird perched on the gun muzzle flies away! Hill 203 has been held!’29

The insistence on the reality of the dead bodies is accomplished by this framing of the story in both images and narrative text. The futility of the task of holding the hill is what comes out as the main argument of this story.30 The hill has been held, but at what cost? There is little hope that the situation will not repeat itself with the new soldiers arriving on the horrible scene. The machine gun, however, stands out as the cold-blooded survivor. With its shining blue steel and large barrel, it has the ultimate design for war. The men needed to operate it, however, do not. The little bird emphasizes this point by flying away from the scene. Unlike the soldiers, it has the freedom to choose whether to stay or leave.

Versaci has pointed out how the frames of ‘Hill 203!’ freeze the action by breaking the scene up into many separate images.31 This pause technique, he argues, opens up a space for reflection on the meaning of war and death that would be difficult to achieve in another medium such as film.32 This technique is repeated, with variations, in this story, where the killing of North Korean soldiers is narrated through a sequence of four frames in which the tremendous power of the machine gun stands against their bodies in varying states of agony and dying.33 The machine gun is also made into a protagonist in this story. The focus on the machines of war in this and other stories in EC’s production emphasizes not only the futility of war, but also pushes a more explicit critique of technological warfare.

‘Hill 203!’, page 1. Art by Jack Davis. Copyright © 1951, William M. Gaines, Agent, Inc. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.

‘Hill 203!’, page 8. Art by Jack Davis. Copyright © 1951, William M. Gaines, Agent, Inc. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.

In ‘Corpse on the Imjin!’, the beginning and end of the story feature an anonymous corpse floating in the water, barely recognizable as human in the early sequences, but at the end looking less like flotsam and more like a lifeless body, floating further and further away. The corpse is in fact, in this case, two different corpses. The first is seen by an American soldier who is seated on the riverbank, and in a philosophical mode he starts to wander off in his mind, trying to figure out how this man died. He starts to think about different ways of dying in the war and rules out a regular fistfight, since physical combat, man to man, has become a rare sight in contemporary warfare. Ironically, a Korean man, his enemy, is watching him from a bush close by. The Korean jumps the American in order to take his food to still his own hunger. The American’s gun is thrown into the river and they are left with only rubble and their fists to fight with. They both fall into the river, still fighting, and eventually the American soldier uses the strength of his arms to hold the Korean under water until he drowns. The corpse floating away in the water at the end is thus another dead man, but this time he is recognizable as a man. The soldiers have seen each other up close, and the American leaves the scene ashamed of what he has done.34

The end sequence shows the body in seven different frames, slowly floating away into the river, with a narrator commenting, first on how the wind and the water is handling the corpse in the river and then on the moral of the story: ‘and it is as if nature is taking back what it has given! Have pity! Have pity for a dead man! [Frame 5] For he is now not rich or poor, right or wrong, bad or good! Don’t hate him! Have pity… [Frame 6] … for he has lost that most precious possession that we all treasure above everything… he has lost his life!’ [Frame 7] Under the last frame, the scenery is commented on again: ‘Lightning flashes in the Korean hills, and on the rain-swollen Imjin, a corpse floats out to sea’.35

The sequence with the frames showing the floating body on the first page, and then again on the last page, again dissects time into the briefest of stills, which together can be seen as a slow-paced room for reflection and contemplation. While the bodies are slowly floating away, there is time to think about what happened here. A life has ended, and, as the opening commentary said, ‘Though we sometimes forget it, life is precious, and death is ugly and never passes unnoticed!’36

When speculating about how the first dead man had died, the American soldier’s first thought was of bombers, F-51s, and 155 mm cannons, all weapons that must have killed ‘thousands of them in this offensive’. While ruling out a fight at close quarters, the soldier thinks: ‘Now with all the long-range weapons, we can kill pretty good by remote control!’ The high-tech weapons seem to obscure the human conditions of war: that actual men are being killed, and that men engage in killing other human beings. Seeing the dead body floating past his position on the riverbank is the spark that helps the American soldier reflect on these things, while the final frames of the dead Korean man, seen only by the reader and the narrator, close the circle, and ask the reader to reflect on the same question, taking the recent experience of the American soldier into account.

An interesting feature of this story is that the American soldier is addressed throughout as ‘you’. This calls for a deeper identification between the reader and the American soldier.37 While ‘you’, the soldier, is asked to actively ponder his actions while confronting his enemy up close, the reader is supposed to put him- or herself in the soldier’s position. Ironically, the narrator asks, ‘Where are the wisecracks you read in the comic books? Where are the fancy right hooks you see in the movies?’38 The comments seem to suggest that, unlike those other silly magazines and movies, this one takes its subject seriously.39 One of the strategies for showing this is to make the reader search his or her own conscience while confronted with the themes of the comics. Considering the fact that many readers could be expected to have first-hand experience of the war in question, this appeal becomes even more effective.

In all three stories, then, the dead bodies are used to invite the reader to reflect on the meaning of death and the consequences of war. The stories underscore somewhat different aspects, of course: ‘Search!’ points to how war works to dehumanize and depersonalize its participants, ‘Hill 203!’ underlines the disproportion between men and the machinery of war, as well as the intrinsic irony of warfare, while ‘Corpse on the Imjin!’ specifically addresses the act of killing and how it changes you, but also how it is wrongfully sanctioned by a state of war.

‘Corpse on the Imjin!’, page 1. Art by Harvey Kurtzman. Copyright © 1952, William M. Gaines, Agent, Inc. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.

‘Corpse on the Imjin!’, page 6. Art by Harvey Kurtzman. Copyright © 1952, William M. Gaines, Agent, Inc. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.

The literary scholar Elaine Scarry has noted that the human body is often the point of departure for making sense of the world. Physical pain or injury becomes a symbol for what is incontestably real, in that it always withdraws from the realm of representation in language.40 In war, this incontestable reality of injured bodies is juxtaposed with the unrealities or fictions of war.41 The way that EC’s war comics relate their stories reflects these ideas by their insistence on looking at dead bodies, while also picturing the ‘fictions’ of war in different senses, often through ironic situations like those portrayed in these three stories. This insistence on looking—or ‘seeing seeing’ as it has been called by the anthropologist Michael Taussig—is a central quality of comics as a medium, where the act of drawing is tightly linked to the act of seeing. In her account of war comics as documentary forms of witnessing, Disaster Drawn (2016), Chute comments on this: ‘Driven by the urgencies of re-seeing the war in acts of witness, comics propose an ethics of looking and reading intent on defamiliarizing standard or received images of history while yet aiming to communicate and circulate.’42 Even if EC’s war comics are not presented as documentary narratives, they share this quality with the comics discussed by Chute.

The stories and how dead bodies are used in them are really just examples of a recurring narrative device in EC’s war comics, where a certain framing—whether it uses a dead body or some other motif—is used to direct the reader’s interpretation. In another story, for example, ‘Tide!’, the tide and the image of a tiny crab in its wake serves the same function.43 This is done by a circular movement, but also with other enforcing measures, such as the narrator’s voice at the beginning and end of the stories, and with how the frames are broken up sequentially on the pages. The motif of the dead body is accentuated by showing it as a whole sequence or in recurring stills, as if creating a moment in time that is so often absent in the action in an actual war. This moment is supposed to be used for a deeper contemplation of what is at stake and the meaning of taking another person’s life. The next part of this chapter will discuss how the stories in turn are framed by their immediate context: the paratexts.

Combat Correspondence and other peritexts

The covers of the war comic books reinforced the anti-war message of the stories, often by portraying condensed situations of war’s irony expressed in a magnified image chosen from one of the stories inside the book. The cover of the thirtieth issue from 1952, for example, has a close-up of a soldier telling his mate behind him ‘Shots from the hill! Douse that light!’, while the soldier behind him is holding out his lit lighter and at the same time being shot before he can hear and follow through on the order.44

Two-Fisted Tales had a bulletin board for readers’ comments entitled ‘Combat Correspondence’. These pages provide an interesting insight to the readership’s attitudes towards EC’s take on war, as well as the motivations of EC’s editors and artists. The bulletin boards of EC’s different magazines reveal how a close relationship developed between the editorial board and the readers, which set them apart in the market for comics in the 1950s:

EC created a self-referential community, winking at inside jokes and speaking with their readers in a slang likely to mystify new readers. The strategy worked, creating a loyalty to the publisher, especially among young adult readers, and the sense that EC was something apart from the standard fare blanketing the newsstands. The first fanzine specifically devoted to comic books was The EC Fan Bulletin, founded by Bhob Stewart in 1953, and Gaines liked the title so much he adapted it for his own promotional newsletter, The EC Fan-Addict Bulletin.45

The bulletin boards in the comic books thus formed a starting point for what would grow into a larger fandom, with EC’s products at its centre.

The mix of letters published on the pages of ‘Combat Correspondence’ shows that the audience for the war magazines was largely teenage boys and men, many of them with experience of war.46 The editors encouraged readers to send in first-hand accounts of their own wartime experiences in order to provide inspiration and secure a higher level of realistic accuracy for the publications. For one reader, asking about the authors’ own experiences of war, the answer was that ‘Our artists all did serve with the armed forces in the last war! Severin was a GI in the Pacific, Elder saw action in Germany and Belgium, Davis served with the Navy in the Pacific, Woody was a Merchant Mariner and a Paratrooper, and Kurtzman was with the state-side Infantry’.47 The exchanges on these matters show that accuracy and first-hand experience were rated highly by editors and readers alike.48

The readers had different responses to the endings too. On some occasions, the comments in ‘Combat Correspondence revealed that not all readers were happy with the anti-war sentiment of the stories published in Two-Fisted Tales. In the twenty-fifth issue of 1952, for instance, two readers wished for ‘better’ endings:

‘Dear Editors, I wish you would change the endings of your stories. I’m sure I’m not the only one who doesn’t like them.’ ‘Dear Editors, I wish you would end your stories better. As it is, they end not so hot.’

The editorial board presents these comments together with an answer for both of them:

We take it that you readers didn’t like the sad endings in some of the stories. But you see, if we gave all the stories happy endings, you might get the impression that war is all happiness… which it is not! We’d like to get other reader’s reactions to this. Do you feel that you’d like all the stories to end happily?—Ed.49

In a later instance of ‘Combat Correspondence’, the editors published a list of comments on the same subject. One of them states that ‘I think it is great to show that war is actually hell, and it shouldn’t be presented as anything else but just that!’ and another writes to tell them to ‘Keep those sad endings, because when I finish them, it makes me sit up and think!’50 Other readers expressed views in line with some of the anti-war statements in the narratives. One example was a letter from a Gary Zeltzer, in Detroit: ‘Dear Editors, After reading your magazine, I realized what war meant. A terrible waste of human life inflicted on both sides. When will the civilized world learn to settle their differences by peaceful methods?’51 Ultimately it was taken as making the stories more authentic: war has no happy ending.

As shown by these examples, the relationship between the editorial board and the EC fans was one of mutual interest and inspiration. According to Gardner, ‘the image of the comics reader as lonely and isolated is itself largely a product of the post-war anxiety about the rising popularity of the comic book form, a form that openly inspired not isolation but collaboration, community, and communication.’52 Those who feared the effect of comics on the young readers’ minds believed that the threat had much to do with the lack of control over what happened in the individual reader’s isolated meeting with the comics.53 This fear did not take into consideration the fact that many of the most devoted EC fans were actually discussing their readings and interpretations with other fans, not to mention the editors.

The endings of Two-Fisted Tales and Frontline Combat resembled the equally moralistic endings of EC’s other publications, such as Tales from the Crypt or The Haunt of Fear, where the main ambition was to horrify their readership. These twist endings were EC’s trademark, who often called for the readers’ opinion about these as well as other ingredients in all their comics. It is interesting to note the similarities as well as the differences between the war stories and the horror stories. Both categories were about the darkest sides of humanity, and just like many of the war stories, the horror stories explored the darkness within. There is one substantial difference, however: the horror stories often described people and events that were entirely fictional, while the war stories strove to be authentic, in the sense that they used realistic war terminology, geographical data, and other factual ingredients.

Other reinforcing techniques

Many of EC’s artists worked on several or all of the comics. In the artwork of the horror stories as well as the war stories, the artists tended to experiment with facial expressions to express the horrified emotions at the depicted atrocities. Many of the war comics portrayed men with their eyes wide open in wordless fear, their faces frozen in extreme agony, in ways that were very similar to the depictions of terrified faces in the comics. The similarities show that the horror of war was every bit as real as the emotions stirred up by the ghastly stories of the horror genre, and the facial expressions of the characters were also an indication of the proper emotions that the reader should experience when reading the stories.54

The generous use of exclamation marks in the war comics—just as in the horror comics—was another way for the creators to stress the horror of the narratives. Just about every sentence ended with an exclamation mark, the titles were exclamatory, as were the final sentences, which so often were stressed on every word by the narrating voice, as in the story ‘Wake!’, which ends: ‘Back in the United States, we thought of war as a soldier’s war and not a civilian’s war! Yet… many civilians gave their lives on Wake Island! And back in the United States, we all found out that whether we wanted it or not, we were all in this war together… soldiers and civilians!’55 This insistent orthography might paradoxically have risked undermining some of the urgency of what was said; however, the endless exclamations also served to point readers in the right direction when interpreting given events on an emotional level: the correct impression should be one of fear, alarm, and outrage, not acceptance or passive disinterest. In some sense, the exclamations are—in this case perhaps more so than in EC’s other publications—a legitimate way to reproduce talk, since what were shown were often life-and-death situations where it was important to make quick decisions and give clear orders.

In the imagery of the war comics there was a surprising lack of blood, entrails, and other visual representations of severe bodily harm, which made them stand out from EC’s horror publications, which were awash in gore. They might have been full of dead or injured soldiers, but the bodies were remarkably ‘clean’ and unspoilt, unlike what must have been the experience of the actual soldiers and ex-soldiers who wrote in to the magazine to tell their stories. This seems to suggest that there were aspects of war that were simply too real to be used as means of providing realistic accuracy. In fact, however strongly the accuracy aspect was stressed by both editors and readers, the staging of war within recognizable and repeatable framings could have worked to create a reassuring distance to events and the memories they evoked. The readers of Two-Fisted Tales and Frontline Combat knew they would not be exposed to an actual war experience in these comics, but rather to a staged scene where the outline and outcome were carefully aligned by the skilled hands of the EC team.

In the horror comics, the ‘editors’ of the bulletin boards were often presented as three fictional (and monstrous) creatures, who also functioned as narrators and presenters of the comic strips: the Crypt-keeper, the Vault-keeper, and the Old Witch, together known as the Ghou-Lunatics. They ‘provided a continual external point of view that kept the reader outside the story. Like the chorus in a Greek tragedy or the proscenium in a theatre, their presence was bizarrely reassuring, a reminder to the reader that it was “just a story”’.56 The lack of a fictional narrator to frame the story meant that the reader’s safe space, assuring him or her that it was ‘just a story’, was not there in the war comics. There was, however, a distinctive narrative voice, framing the story and providing a moral standpoint for the reader’s interpretation of events, and this voice could easily be understood as the collective moral standpoint of the same ‘editors’ who were responsible for the ‘Combat Correspondence’ page. The strong presence of the editorial board, thus, had a reassuring function.

Even if these stories should not be read as ‘just stories’, they were clearly recognized to be hypothetical constructs. As Tom Gunning points out, ‘the power of comics lies in their ability to derive movement from stillness—not to make the reader observe motion but rather participate imaginatively in its genesis.’57 In its visual dimensions, comics also differ from other media, which use mainly photographic images: ‘The artist not only depicts something, but expresses at the same time a visual interpretation of the world, with every drawing style implying an ontology of the representable or visualizable.’58 The medium, with its insistence on the reader accepting an active role in the genesis of the story and the world depicted according to the vision of the artist, thus underscores the importance of interpretation, and invites the reader to share a symbolic representation of events, whether they are realistic or not.

Some of the issues of Two-Fisted Tales introduced the specific artists involved in the series as ‘the artist of the issue’ with a photograph and a longer text, which tended to give a presentation of the individual behind the scenes. It was common to mention where and in what capacity the artist had served in the military; another was to say how he had met his wife.59 In the presentation of Jack Davis, for example: ‘But all work and no play made Jack a dull life, so he headed south to fetch himself a wife. And he fetched a beauty too! Name’s Deena!’60 These personal stories were told with a tone of familiarity, and often ended with a comment about what a good fellow he was, well-liked by both fans and co-workers. The presentation mixed these ingredients with hard facts about the person’s experience of war and his life as a hard-working artist. The ‘artist of the issue’ feature thus individualized the team behind the comic books and built their personas and credibility among their audience.

The bulletin board was also at times used to discuss the work of individual artists, and the editors could on such occasions highlight the specific trademarks of an artist, which facilitated the recognition of their work. The mentions of individual artists reflected a deep admiration and mutual respect on the part of the comics’ creators—hence the editors’ description of the specific circumstances of an issue in 1953, when Kurtzman, who normally would ‘mastermind … the mag from cover to cover’, fell ill with jaundice and had to be admitted to hospital.

Harvey managed to write the Guynemer story for Evans while the nurse wasn’t looking … Jack Davis turned out script and art for ‘Betsy’ single-handed … Wally Wood came up with the solid ‘Trial By Arms’ theme, which Jerry embellished … and Jastly Jerry managed to find time to write the French Foreign Legion story for Severin. In all this, of course, Harvey had a HAND … rather than, as per usual, being up to his NECK! All the boys came through wonderfully in the pinch, and deserve much praise … which I hereby bestow!—William M. Gaines, Managing Editor (Oh, yes … Harvey is coming out of the hospital now and coming along nicely as of this writing!)61

The tone is frank, humorous, and familiar, which made it easier for readers to develop a connection with the makers of the comic books. The constant stress on the attention to detail, and on the skills and experience of the various artists, also encouraged the readers to appreciate the artwork, and to understand it as such and not just amusement. In the evolving dialogue between creators and consumers, a basis for a new view of comics as a form of art was laid out, one that implied a non-conformist ideological stance.

The effort to build individual trademarks out of EC’s various artists bore fruit, as was seen at the launch of what was to become their next flagship, MAD. An advertisement featured all the artists, drawn by themselves, with Kurtzman holding up the new magazine: ‘We at EC proudly present our latest baby …. A ‘comic’ comic book! This is undoubtedly the zaniest 10 [cents’] worth of idiotic nonsense you could ever hope to buy! Get a copy of MAD… on sale now! We think you’ll enjoy it!’62 In MAD, this self-ironic use of the artists’ portraits became a standard feature.

The readers were often treated as having the agency to change EC’s production in different peritexts. This was especially the case with the ‘Combat Correspondence’ page, but also in a repeat advert for other EC productions that stated: ‘You’ve written! You’ve telegraphed! You’ve phoned! You’ve threatened us! So here it is! The magazine you’ve demanded!’, followed by an issue of, say, Weird Fantasy or Shock! Suspensestories.63 The tone adopted towards readers was often more familial than respectful, but it was still clear that the editors listened attentively to reader’s demands and did their best to accommodate them, as long as it did not conflict with EC’s ideals and standards.

The paratextual ‘frames’ provided by the ‘Combat Correspondence’ page and other peritexts, provide different but combinable perspectives to the stories narrated in the comics. Firstly, they underscore the importance of historical and factual accuracy as a means to add authenticity to the war stories. Second, they set out some of the intentions of the producers while also providing them with an aura of skilled expertise and artistry. Third but not least, they provide a setting where the audience is invited in to the production and evaluation of the stories and their artwork. This setting is also to be interpreted as a place where likes and dislikes, and indeed the political and moral ideals of readers and EC co-workers, were welcome and discussed, in a way that helps the interpretation of the narratives from a moral standpoint. This function was further developed by the framing of stories within the stories themselves, using the different narrative devices discussed earlier.

Adding layers of paratexts

The collected EC Archives edition of Two-Fisted Tales consists of three volumes. All include forewords and introductions by the various editors and other experts on EC’s work. The stories have been recoloured for the new edition, but with the express aim of faithfully reproducing the style of the original artist, Marie Severin—the only female member of the EC staff.64

In providing new material, consisting mainly of commentaries and advertisements for other titles in the EC Archives series, the editors of the collected volumes of Two-Fisted Tales gave their comic fiction new, stronger ‘frames’. These frames generally supported the interpretation of the anti-war message of the war comics, as when commentaries were given under the heading ‘EC: War is hell’, with interpretations and analysis of select artworks along with quotes from the artists. In this way, they provide today’s readers with information that helps to see these war comics in a historical and ideological context. The material also serves to further highlight the sheer artistry of the comics. One example is when Russ Cochran explores ‘Editorial Style in the EC Comics: Feldstein and Kurtzman’ or ‘Kurtzman’s Cinematic Style’; another when Versaci shares his analysis of chosen stories, such as ‘Jeep!’ or ‘Hill 203!’65

Some of the additional material consists of memoirs or comments by the artists themselves. In Volume 1, Cochran has a piece about ‘Working with Kurtzman’, and Volume 3 has a foreword written by former staff member Joe Kubert, who states that he ‘learned a lot from Harvey Kurtzman’, and goes on to give a personal account of what it was like to follow his lead.66 This type of material consciously adds to the mythologizing of EC and its artists. In a sense, these editions can be seen as an extension of fan-based activity centred on EC’s trademark—they certainly conflate the roles of producer and consumer in a way typical for what has been labelled convergence culture.67 The fans have taken on the task of maintaining the production of EC’s comic books while striving to stay as close as possible to the style of the originals. When advertising for the rest of the collected EC Archives titles, for instance, the style of the original advertisment has been imitated, while also adding information of interest to the modern day reader:

The EC Archives proudly presents Tales from the Crypt. Tales from the Crypt is the best-known and most popular comic in the EC line! This comic book has spawned several feature films and the HBO series! Vampires, werewolves and ghouls galore! Great horror stories with art by the best comic artists in the business!68

The edition is thus addressed to already devoted fans, wanting to complete their private collections of EC’s work, and to potential new readers, interested in EC because of its legacy and great artwork.

Conclusion

In EC’s war comics, form and content come together to convey the main anti-war message of its publishers. The tools used, both in the magazines as whole and in separate comics, can be described in terms of framings that operate on different levels to guide the reader’s interpretation. The motif of the dead body in the analysed stories is an example of a narrative device that is repeated with variations in many of the war stories. The dead body is shown through sequences of stills that force the reader to actually look at it and ponder what made it take this unnatural state. Using the dead body is also one of many ways to create a circular movement in the stories, where the beginning and end serve to ascribe a moral outlook or perspective to the events recounted in the comics, and the return back to the beginning serves as a kind of ‘framing’ of the stories on a metaphorical level.

As paratexts, the same messages are enforced by their moral framings, such as the discussion of sad and happy endings on the bulletin board, or by stressing the accuracy of the backstories. Yet the paratexts also signal an openness to interaction with readers, who also have a relevant background that is used to improve the comics. In addition, the paratexts provide information about the comics’ creators, and frame this as information on artworks rather than ‘just for entertainment’. The close relationship built up between creators and consumers with the help of these paratexts has helped construct a legacy around EC’s trademark, where the brand has come to represent quality and seriousness as well as humour and a general cult status.

As a mediator of war, EC worked to question rather than justify it, while taking soldiers’ first hand-experiences into serious consideration. The plots, like the artwork, stressed the proximity of war to horror, suggesting that war changes those caught up in it in ways that extend far beyond the cessation of the fighting. The suggestion is that to be morally outraged, or even shocked beyond disbelief, is the normal response to what war asks of human beings. The many framings found in EC’s comic books were safety devices in the sense that they existed to ensure that, unlike other successful comic books of the day, the message could not be misread, while also providing the reader with tools to deal with very real experiences within a reassuring and confined context.

Notes

1 Chris York & Rafiel York, introduction in eid. (eds.), Comic books and the cold war: Essays on graphic treatment of communism, the Code and social concerns 1946–1962 (Jefferson: McFarland, 2012), 5–15 at 5.

2 Jean-Paul Gabillet, Of comics and men: A cultural history of American comic books, tr. Bart Beaty & Nick Nguyen (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2010), 197 (first pub. as Des comics et des hommes 2005); see also Hillary L. Chute, Disaster drawn: Visual witness, comics, and documentary form (London: Belknap, 2016), 11.

3 Gabillet 2010, 197–8.

4 Rocco Versaci, foreword in The EC archives: Two-fisted tales (2007), ii. 7; and Christopher B. Field, ‘“He was a living breathing human being”: Harvey Kurtzman’s war comics and the “Yellow Peril” in 1950s containment culture’, in York & York 2012, 45–54; Rocco Versaci, This book contains graphic language: Comics as literature (London: Continuum, 2007); Jared Gardner, Projections: Comics and the history of twenty-first-century storytelling (Stanford: SUP, 2012); Robert S. Petersen, Comics, manga, and graphic novels: A history of graphic narratives (Denver: Praeger, 2011), 158.

5 Other material has been taken from advertisements for other products than EC’s own as necessary for economical purposes (EC archives 2014, iii. 4–7). Note that the issues of the original magazines started at number 18 but are numbered from number 1 in the reprinted Archives-edition, in the first two volumes. The third and last volume, however, follows the original issue numbers and calls the last six issue numbers 30–35, accordingly.

6 Versaci, foreword in EC archives 2007, ii. 7.

7 EC archives 2007, ii. 2, 18; see also Field 2012; Versaci 2007.

8 David Hajdu, The ten-cent plague: The great comic-book scare and how it changed America (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2008), 195; Gabillet 2010, 38–9.

9 Gabillet 2010, 39.

10 Leonard Rifas, ‘Korean War comic books and the militarization of US masculinity’, Positions: East Asia cultures critique, 23/4 (2015), 619–31 at 619–20.

11 Gérard Genette, Paratexts: Thresholds of interpretation, tr. Jane E. Lewin (Cambridge: CUP, 1997, first pub. as Seuils 1987).

12 Genette 1997, 5.

13 Marie Maclean, ‘Pretexts and paratexts: The art of the peripheral’, New Literary History, 22/2; Probings: Art, criticism, genre (1991), 273–9 at 273.

14 Erving Goffman, Frame analysis: An essay on the organization of experience (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1986), 21.

15 See, for example, Dennis Chong & James N. Druckman, ‘Framing theory’, Annual Review of Political Science, 10 (2007), 103–26; Dietram A. Scheufele, ‘Framing as a theory of media effects’, Journal of Communication, 49/1 (1999), 103–122; and Gail T. Fairhurst & Robert A. Sarr, The art of framing: Managing the language of leadership (San Francisco: Josey-Bass, 1996).

16 Scheufele 1999, 106.

17 Pascal Lefèvre, ‘Mise en scène and framing: Visual storytelling in Lone Wolf and Cub’, in Matthew J. Smith & Randy Duncan (eds.), Critical approaches to comics (London: Routledge, 2012), 71.

18 Chute 2016, 17.

19 Thierry Groensteen, The system of comics, tr. Bart Beaty & Nick Nguyen (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1999), 31 (first pub. as Système de la bande dessinée).

20 Tom Gunning, ‘The art of succession: Reading, writing, and watching comics’, Critical inquiry, Special issue: Comics & media (2014), ed. by Hillary Chute & Patrick Jagoda, 36–51, quote at 50.

21 Lefèvre 2012, 24.

22 Chute & Jagoda 2014, 3.

23 ‘Bug out!’ in EC archives 2007, ii. 19.

24 ‘Lost batallion!’ in EC archives 2014, iii. 89.

25 When it comes to dead bodies specifically, this also happens: for example, in ‘Jeep’ in EC archives 2007, ii. 137; and ‘Massacred’, in EC archives 2014, iii. 79.

26 ‘Search!’ in EC archives 2006, i. 1–6, 137–43; ‘Hill 203!’ and ‘Corpse on the Imjin!’ in EC archives 2007, ii. 11–18 & 63–8.

27 For example in the stories ‘War story!’ and ‘Old soldiers never die!’ (EC archives 2006, i. 45–54, 189–98) and ‘D-Day!’ and ‘Fire mission!’ (EC archives 2007, ii. 131–6, 205–211).

28 ‘Hill 203!’ EC archives 2007, ii. 11.

29 Ibid. ii. 2, 18.

30 See also Versaci 2007, 167–9.

31 Ibid. 167–9.

32 Ibid. 169.

33 Ibid. 169. The technique of breaking up scenes into several stills was also common in EC’s war comics.

34 See also Versaci 2007, 164.

35 ‘Corpse on the Imjin!’, EC archives 2007, ii. 68.

36 Ibid. ii. 63, original emphasis.

37 Field 2012, 49 talks of this ‘you’ function in another storyline in EC’s war comics, concluding that ‘This has the effect of emphasizing the reader’s complicity with the American soldier’s actions in the story.’

38 ‘Corpse on the Imjin!’, in EC archives 2007, ii. 65.

39 Versaci 2007, 139–81 discusses at length the differences between film and comics, and specifically EC’s war comics.

40 Elaine Scarry, The body in pain: The making and unmaking of the world (Oxford: OUP, 1985), 27.

41 Scarry 1985, 125.

42 Chute 2016, 31.

43 ‘Tide!’ in EC archives 2014, iii. 105–111.

44 Cover by Jack Davis for EC archives 2014, iii. 13.

45 Gardner 2012, 98.

46 There are, however, occasional women readers who enjoy the war stories, as pointed out by Miss Nancy Cash, in Louisville: ‘Dear Editors, You may think your magazine appeals only to men! However, I want you to know that I enjoy it as much as any man!’ (‘Combat Correspondence’, in EC archives: Two-fisted tales, No. 22, Jul.–Aug. 1951).

47 EC archives 2007, ii. 28.

48 See also Hajdu 2008, 197 who comments on Kurtzman’s high ambitions when it comes to realism.

49 EC archives 2007, ii. 62.

50 Ibid. ii. 130.

51 Ibid. ii. 96.

52 Gardner 2012, 104.

53 Ibid. 104.

54 See also Sturfelt’s and Qvarnström’s chapters in this volume.

55 ‘Wake!’, in EC archives 2014, iii. 36, original emphasis.

56 Digby Diehl, Tales from the crypt: The official archives including the complete history of EC Comics and the hit television series, designed by David Kaestle & Rick Demonico (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1996), 43.

57 Gunning 2014, 50.

58 Lefèvre 2012, 16.

59 EC archives 2007, ii. 11.

60 Ibid. ii. 44.

61 EC archives 2014, iii. 166.

62 Ibid. iii. 12.

63 See, for example, the advert in EC archives 2007, ii. 162.

64 Stated in EC archives 2014, iii. 6.

65 EC archives 2006, i. 110, 178; EC archives 2007, ii. 42 (analysis of ‘Hill 203!’), 178 (analysis of ‘Jeep!’); EC archives 2014, iii. 166.

66 EC archives 2006, i. 12; EC archives 2014, iii. 9.

67 Henry Jenkins, Convergence culture: Where old and new media collide (New York: NYUP, 2006).

68 EC archives 2006, i. 78.

References

Chong, Dennis & James N. Druckman, ‘Framing theory’, Annual Review of Political Science, 10 (2007), 103–26.

Chute, Hillary, Disaster drawn: Visual witness, comics, and documentary form (Cambridge: Belknap, 2016).

—— & Patrick Jagoda, ‘Introduction’ Critical inquiry, Special issue: Comics & media, 40/3 (Spring 2014), 1–10.

Diehl, Digby, Tales from the crypt: The official archives including the complete history of EC Comics and the hit television series (New York: St. Martin’s, 1996).

The EC archives: Two-fisted tales, 3 vols (West Plains: Gemstone, 2006–2014).

Fairhurst, Gail T. & Robert A. Sarr, The art of framing: Managing the language of leadership (San Francisco: Josey-Bass, 1996).

Field, Christopher B, ‘“He was a living breathing human being”: Havery Kurtzman’s war comics and the “yellow peril” in 1950s containment culture’, in York & York 2012, 45–54.

Gabillet, Jean-Paul, Of comics and men: A cultural history of American comic books, tr. Bart Beaty & Nick Nguyen (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2010) (first pub. as Des Comics et des Hommes, 2005).

Gardner, Jared, Projections: Comics and the history of twenty-first-century storytelling (Stanford: SUP 2012).

Genette, Gérard, Paratexts: Thresholds of interpretation, tr. Jane E. Lewin (Cambridge: CUP, 1997) (first pub. as Seuils 1987).

Goffman, Erving, Frame analysis: An essay on the organization of experience (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1986).

Groensteen, Thierry, The system of comics, tr. Bart Beaty & Nick Nguyen (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1999) (first pub. as Système de la bande dessinée).

Gunning, Tom, ‘The art of succession: Reading, writing, and watching comics’, Critical inquiry, Special issue: Comics & media, 40/3 (2014), 36–51.

Hajdu, David, The ten-cent plague: The great comic-book scare and how it changed America (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2008).

Jenkins, Henry, Convergence culture: Where old and new media collide (New York: NYUP, 2006).

Lefèvre, Pascal, ‘Some medium-specific qualities of graphic sequences’, SubStance #124, 40/1 (2011), 14–33.

—— ‘Mise en scène and framing: Visual storytelling in Lone Wolf and Cub’, in Matthew J. Smith & Randy Duncan (eds.), Critical approaches to comics (New York: Routledge, 2012), 71–83.

Maclean, Marie, ‘Pretexts and paratexts: The art of the peripheral’. New Literary History, Special issue, Probings: Art, criticism, genre, 22/2 (Spring 1991), 273–9.

Petersen, Robert S., Comics, manga, and graphic novels: A history of graphic narratives (Denver: Praege, 2011).

Rifas, Leonard, ‘Korean War comic books and the militarization of US masculinity’, Positions: East Asia Cultures Critique, 23/4 (2015), 619–31.

Scarry, Elaine, The body in pain: The making and unmaking of the world (New York: OUP, 1985).

Scheufele, Dietram A., ‘Framing as a theory of media effects’, Journal of Communication 49/1 (1999), 103–122.

Versaci, Rocco, This book contains graphic language: Comics as literature (New York: Continuum, 2007).

—— foreword in The EC archives 2007, ii. 7.

York, Chris & Rafiel York, ‘Introduction’ in York & York 2012, 5–15.

York, Chris & Rafiel York (eds.), Comic books and the Cold War: Essays on graphic treatment of communism, the Code and social concerns 1946–1962 (Jefferson: McFarland, 2012).