CHAPTER ONE

Well Read in Poetry, Fair in Knowledge

Henry and Emily Form a Team

And by good fortune I have lighted well

On this young man, … well read in poetry

And other books—good ones, I warrant you.

The Taming of the Shrew, 1.2.169–72

Thou art as fair in knowledge as in hue.

Sonnet 82.5

AFTER THE CIVIL WAR, a newly muscular American economy became seriously competitive with Europe in international affairs. Culturally, too, the affluent middle and upper classes began, at about the time of the centennial, to resent the long-nosed disapproval of foreign commentators. For every Alexis de Tocqueville and James Bryce who mostly admired American individualism and risk-taking daring, there had been a Frances Trollope or dyspeptic Charles Dickens mocking the country’s rough-hewn manners. Henry James and Henry Adams were among the vocal cultural critics who despaired that America was fated to play merely a cameo role in the grand civilizing drama of Continental culture, which honored a past America ignored. In historic Boston, where Henry James returned in 1904 after a twenty-year absence, he sniffed, “What was taking place was a perpetual repudiation of the past, so far as there had been a past to repudiate … The will to grow was everywhere written large, and to grow at no matter what or whose expense.”1

The drive for material success over all would doom the nation’s cultural institutions to the second rank. To be sure, wealthy Americans such as Jenny Jerome were eagerly sought-after marriage material for land-poor English aristocrats like the Duke of Marlborough, but the exchange was perceived, as the novels of Edith Wharton and Henry James show, as trading money for lineage and social gloss. Frances Trollope’s younger son, Anthony, took his second-generation shots in books like The American Senator (1877) and other novels where American visitors are usually foils, bumptious and crude.

Many native-born American industry leaders and inheritors of wealth supported the arts and wanted the United States to equal Europe as a patron. Henry Clay Frick may have been one of “the Worst American CEOs of All Time,” rivaling John D. Rockefeller for the dubious sobriquet “most hated man in America,” but the opulent Frick Collection opened to the public on Fifth Avenue in 1935 housed a treasure trove of Rembrandts, El Grecos, Corots, Goyas, and more.2 Frick’s close friend Andrew Mellon endowed the National Gallery of Art, and Rockefeller’s philanthropies continue today in the fourth generation of that family. The story of Henry Clay Folger—self-effacing, self-made colleague of John D. Rockefeller and Charles Pratt and ultimately president of Standard Oil of New York—is another American story giving the lie to the notion that every Gilded Age striver cared only for personal wealth.

The seed of the world-renowned Folger Shakespeare Library was sown when Emily Jordan, “fair in knowledge,” and Henry Folger, “well read in poetry and other books,” attended a beach picnic and realized they shared a passion for Shakespeare. On June 7, 1882, members of the Irving Literary Circle of Brooklyn traveled to nearby Sands Point on Long Island Sound. The menu for the club’s third annual excursion was hearty and extensive in the Edwardian mode: mock turtle soup, baked black bass with white wine sauce, ribs of beef, lamb, spring chicken, vegetables, pickles—and, to refresh the palate if not trim the waistline, plum pudding with vanilla ice cream. After the feast, toastmaster Charles Pratt, the oil refiner and philanthropist, proudly turned to twenty-five-year-old Henry, who quoted lines from As You Like It. With a twinkle, Pratt then asked Emily Clara Jordan for a toast, which included a passage from Othello. Young Charlie Pratt and his sister Lillie, a Vassar chum of Emily, may have been up to a little matchmaking. But the young picnickers could hardly foresee that the bookish Henry and Emily would marry three years later, much less build a world-class research library in the depths of the Great Depression.

Henry Folger‘s quiet presence at the picnic showed a scholarly demeanor that had already impressed Pratt. Henry revered Pratt not only because he had paid for part of Folger’s junior year at Amherst after Henry’s father went bankrupt but also because, one week after college graduation, Pratt became his boss. Anxious to pay off his debt, Henry entered Pratt’s oil business in June 1879.

Although new to the literary circle at the picnic, Emily Jordan had just been elected its president and recently begun her first teaching job in Brooklyn. Unlike Henry, who had grown up only in Brooklyn, Emily and her family had roamed from Ironton, Ohio, to Flushing, New York, to Elizabeth, New Jersey. Like Henry, but unlike most women of her generation, she, too, attended college. Graduating from Vassar in 1879, she became a teacher in the collegiate department at Miss Hotchkiss’s School, also known as the Nassau Institute. She rented a flat at 65 Quincy Street, right across the street from the Folger family home.

Lillie Pratt had introduced Emily to Henry at a meeting of the Irving Literary Circle at the stately Pratt home at 232 Clinton Avenue in Brooklyn. Henry attended these meetings as early as 1880. By then he had compiled a chart in his small, fine clerk’s hand in violet ink, noting the strengths, weaknesses, and stylistic differences among Burns, Byron, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Longfellow, and Tennyson. The studious group also explored American political and social history, discussing the colonial and federal periods, slavery, and reconstruction. Emily and Henry met occasionally at the Literary Circle and soon realized they shared a similar upbringing, education, and interests. Each carefully preserved the Sands Point picnic program, one of the few identical items to be found in both their scrapbooks. Perhaps they knew this picnic had begun their lifelong partnership with William Shakespeare and with each other.

Henry’s blue-eyed ancestors had little interest in literature. Enterprise and business acumen distinguished the Folgers, who had lived on Nantucket Island off the Massachusetts coast for three hundred years and continue there today. Blacksmiths, carpenters, and seamen, they supported the bustling whaling trade. They were too busy to collect scrimshaw, decorated quarterboards, or barrel staves. Of Flemish descent, Peter Folger (originally spelled Foulger)—the first and most colorful of the island’s Folger clan—was born in Norwich, England, in 1617. He sailed with his parents to Massachusetts in the late 1620s. On Nantucket, he apprenticed for many trades: surveyor and blacksmith, miller and joiner, court clerk and recorder, school teacher and missionary. Adept in languages, he learned the Algonquian tongue of the Wampanoags. Practical, he fabricated and used machinery. Literary, he wrote poetry. Peter was a baptized Congregationalist who became a Baptist and showed sympathy with Quakers. Folger’s last child with Mary Morrel was a daughter, Abiah, born in 1667. Abiah became the second wife of Boston soap maker Josiah Franklin, and at age forty-one she gave birth to Benjamin Franklin. In homage to this distant connection, Henry Folger maintained that had he not collected Shakespeareana, he would have collected Frankliniana.3

Henry’s blue-eyed ancestors had little interest in literature. Enterprise and business acumen distinguished the Folgers, who had lived on Nantucket Island off the Massachusetts coast for three hundred years and continue there today. Blacksmiths, carpenters, and seamen, they supported the bustling whaling trade. They were too busy to collect scrimshaw, decorated quarterboards, or barrel staves. Of Flemish descent, Peter Folger (originally spelled Foulger)—the first and most colorful of the island’s Folger clan—was born in Norwich, England, in 1617. He sailed with his parents to Massachusetts in the late 1620s. On Nantucket, he apprenticed for many trades: surveyor and blacksmith, miller and joiner, court clerk and recorder, school teacher and missionary. Adept in languages, he learned the Algonquian tongue of the Wampanoags. Practical, he fabricated and used machinery. Literary, he wrote poetry. Peter was a baptized Congregationalist who became a Baptist and showed sympathy with Quakers. Folger’s last child with Mary Morrel was a daughter, Abiah, born in 1667. Abiah became the second wife of Boston soap maker Josiah Franklin, and at age forty-one she gave birth to Benjamin Franklin. In homage to this distant connection, Henry Folger maintained that had he not collected Shakespeareana, he would have collected Frankliniana.3

Samuel Brown Folger (1795–1864), Henry’s grandfather, was a master blacksmith in Nantucket shipbuilding and harbor works when whaling was at its apogee and islanders manufactured candles and sold sperm oil for lighting. From time to time, antiques auctions still turn up double-flued harpoons or cutting-in spades stamped with the initials “SBF.”4 Samuel named his son Henry, third of nine children, after Henry Clay, the statesman he most admired. In the 1840s, Nantucket died as a whaling center because oil extracted from the ground and refined as kerosene became a better source of light and its byproducts were in demand. The Folger children scattered. A fragile child, Henry Clay Folger Sr. left school at fourteen to work in a Nantucket bookstore run by Andrew Macy, brother of the founder of Macy’s department store. Two years later, Henry paid three dollars to sail to New York. Headwinds, storms, and a cautious captain prolonged the trip to two weeks.

Two more of Samuel’s sons also left Nantucket heading west. Edward, followed by his youngest brother James A. Folger, was lured by the Gold Rush. The brothers boarded steamers for California by way of the Isthmus of Panama. Fifteen-year-old James, who had to stay in San Francisco to pay off his travel costs, built a coffee mill. At mid-century, well-roasted select coffee was still a considerable luxury. James did well and, in 1872, started Folger’s Coffee, providing the first industrial service in San Francisco to roast, grind, and package coffee. The company still exists, producing popular coffee and a jingle:

The best part of waking up

Is Folger’s in your cup.

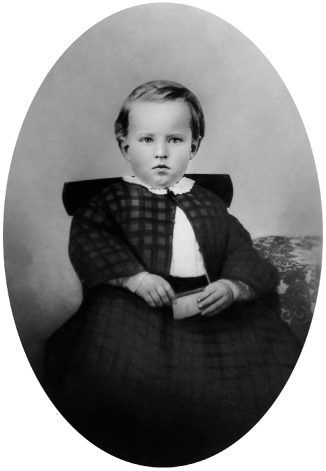

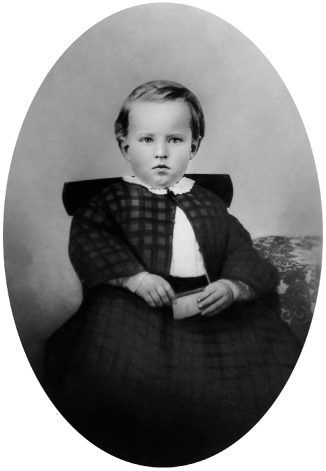

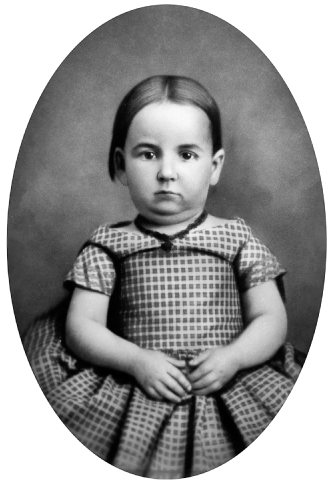

After seeing off Edward, Henry Folger Sr. doubted he could find a good job back in Nantucket, and determined to become financially independent. Just seventeen, he took a job at the wholesale milliners Blake & Brown on 71 William Street in Manhattan. Known for industry and reliability, he stayed with the firm a dozen years. In spring 1856 he married a grade-school teacher, Eliza Jane Clark, a young woman with fourteen siblings whose family had lived in New York City since the eighteenth century. The Presbyterian wedding ceremony lasted only fifteen minutes before the Folgers sped off in a carriage to catch the Fall River boat to Nantucket for a two-week honeymoon. The bridal couple settled in at 142 Franklin Street in Manhattan, where Henry Clay Folger Jr. was born in 1857. Seven more children came along, but his mother’s love of teaching and learning passed mostly to her eldest. One of Henry Jr.’s earliest memories was reading while rocking a cradle with his foot. Young Henry had a propensity for holding a book, as a photograph shows him. It was to be the first of 92,000 books. The first five children arrived before the oldest was five, a “good average,” wryly pronounced the father, reflecting at age 74.5 Twins George and James died in infancy, and sister Lizzie died when a teenager.

We know little about Eliza (called “Lida”) Jane Clark Folger, Henry Jr.’s mother, though her face is animated by warmth and devotion in a portrait with her baby son. In a simple black dress with white lace collar, hair neatly pulled back and parted in the middle, the young woman with the steady gaze whom Henry Sr. courted and married in 1856 affirms his laconic description of her as “a very nice pretty girl.” She was good with figures—a skill young Henry inherited—and ably managed a large household. Emily Folger recalled that her mother-in-law was beloved for her unassuming presence and energetic arrangement of children’s picnics and Coney Island excursions.

Eldest of eight children, Henry Clay Folger Jr. clutches the first of his 92,000 books, ca. 1862. By permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library

Henry Folger Sr.’s wavy hair and horseshoe mustache cut a handsome figure. He was known as a crack salesman, giving up millinery to work in water meters. He became partner, and later president, of Dynamometer and later worked with three other firms. His name appears as a witness when his boss John Thomson applied for a U.S. patent on a more accurate, dependable water meter. Henry invested, too, but his fortunes plunged during the Panic of 1873, when he “went out of business with 75 cents in my pocket.” Retiring on half pay, the aged Henry Sr. occasionally sent cash to his son to buy a few shares of Standard Oil stock. When he died in 1914 he had amassed a modest 116 shares through his own contributions and his son’s help.6

Henry Sr. changed residences even more often than jobs. He moved his family twelve times in Manhattan and Brooklyn and lived for three years in upstate Troy, New York. Looking back, he wrote, “I had a hard struggle to earn enough by selling goods on commission to keep my household expenses going for two or three years, but my family were loyal and did all they could to help, and our struggles cemented our love.”7

Henry Sr. left solid legacies. By example, he taught his children a firm Protestant work ethic. Valuing every cent he earned, he had a survivor’s ability to adapt to changing markets. He had strong faith that he could provide for his brood and the self-reliance to weather temporary adversities. In this family of teetotalers, regular churchgoing was expected and music was encouraged. The father conveyed to his children his love of music. He played the organ in several churches, led the congregation and Sunday school in hymn singing, and assembled a quartet choir. At home, he taught young Henry to play the organ. On Sundays he drove his children (and later, the grandchildren) in his trap, a small horse-drawn carriage.

The Folger family exuded affection, frugality and trust in divine wisdom. Henry Sr. customarily gave his children, no matter their age, a symbolic birthday gift of 100 pennies, challenging them to see how far the coppers could go. As his wife lay dying, in 1889 he wrote his daughter-in-law Emily:

It is possible that I shall be called out of the city the last of this or first of next week, so I enclose to you 100 cents to put under the Jr’s plate, or in the toe of his stocking, or any where else you may think best, on the 18th inst, and it is with pleasure that I send it as a reminder of our love for him, and at this time he seems more dear to us as we realize how much his mother loves him, and how soon she will be called up to her other loved ones waiting for her, and will be waiting for us to follow, which I feel will not be long. You also share our love, and we wish you all the happiness that can be given to you both, and may your lives be free from sorrow as God in His goodness thinks is best. With love from us all, Your Afft Father8

Henry Jr.’s three brothers, William, Edward, and Stephen, followed him into the oil business. Edward and Stephen worked at Standard Oil, both becoming executives. William worked as a stockbroker and Stephen had a sideline as a jeweler. Mary Folger—the only female Folger sibling to survive into adulthood—married Enoch Harden Wells and bore three daughters. After Enoch died young, childless Emily and Henry heaped generosity and affection on the Wells girls. Each received a ring—one with diamonds and emeralds, one with diamonds and sapphires, the third with rubies—and Henry financed their Vassar education.9

Years later, after Henry died, Emily lured his niece’s husband, Owen Fithian Smith, from an executive post at National City Bank in New York to serve as her banker, financial secretary, and executor of Henry’s will in negotiating with Amherst trustees on Folger Library plans, personnel, and policies. The Folger family was close-knit, exchanging regular notes, Christmas presents, and birthday gifts. By far the most affluent, Henry regularly showered his sister and brothers with significant cash payments.

Henry never strayed far from his New England roots. He was an avid collector of books on Nantucket, although he professed limited interest in his own genealogy, and no record exists that he visited the island.10 Even so, Nantucket appeared as a candidate on the list of possible sites for Henry’s monumental Shakespeare library. He became an accomplished sailor, after many boyhood summers spent in Camden, Maine, on Penobscot Bay. He took the Eastern Steamship Corporation steamer overnight from Boston and arrived at Mrs. Clara E. Palmer’s guesthouse, Cedarcrest, on upper Chestnut Street, in a barouche, in the early morning.

As a schoolboy, Henry Folger showed academic promise early. The first sign took the form of engraved certificates from P.S. 15 in Brooklyn. Not one to creep “like snail / Unwillingly to school” (As You Like It, 2.7.153–54), at thirteen, Henry showed his parents the first of what would become a stack of merit awards: “As an honorable testimony of approbation for industry, punctuality and good conduct during the last month.”11 These certificates bore the signature of P.S. 15’s principal, Stephen Gale Taylor, who moved to nearby Adelphi Academy as principal in 1875, tracking Henry’s school career. Mementos from Henry’s school days include a poem, an essay on Cicero, and “Scenes at an Auction.” The auction room he describes would become a familiar haunt in later book-collecting years. Henry read widely, too: Tennyson, Goldsmith, Longfellow, Keats, Milton, but apparently no Shakespeare or Emerson. Perhaps Henry was indeed drawn to the Bard as much by Emily as by his early love of reading.

In 1875, as he packed for freshman year at Amherst, Henry received the first of many solicitations that arrived throughout his long life. Startlingly, his elementary school needed money. We can imagine young, earnest Folger studying the constitution and by-laws of the Graduates’ Association of P.S. 15. He must have nodded as he read, “Object: to promote in every proper way the interests of the School, and to foster among the graduates a sentiment of regard for each other, and an attachment to their alma mater.” By the end of his life, Folger would lavishly redefine the concept of devotion to one’s alma mater.

His college preparatory school, Adelphi Academy, deeply affected Henry. When the cornerstone was laid at 412 Adelphi Street in northwest Brooklyn in 1863, founding supporter Reverend Henry Ward Beecher in his address declared this was no ordinary school: “No man can give any reason why a woman should not be educated as well as and in the same respect which, a man is educated.” This rare coeducational institution later boasted the first gymnasium in Brooklyn. Dedicated to building both strong minds and bodies, the school adopted a strangely stark motto: “Life without Learning Is Death.”

Folger was impressed by Adelphi’s emphasis on strong moral values and academic excellence. Besides Beecher, two other founding members greatly influenced the school, Brooklyn notables Horace Greeley and Charles Pratt. All three served on a committee that helped Adelphi expand its physical plant and academic programs. Greeley was a teacher, lecturer, newspaperman, and moral leader who spoke out for labor unions and against slavery and capital punishment. Beecher, a fiery abolitionist and mesmerizing preacher, was named the first pastor of Brooklyn’s Plymouth Congregational Church in 1847 and remained there forty years, despite being defendant in a notorious 1875 trial for adultery with a congregant, the wife of a friend. Henry was conscious of his good fortune in being exposed to an unusually progressive education.

Charles Pratt was wealthy mentor and friend to young Henry. But at ten, in 1840, he had been selling newspapers on a corner in Watertown, Massachusetts. At forty-four, in 1874, Pratt became president of the Adelphi board of trustees, endowing a scholarship fund and introducing prizes for academic excellence. Emily Folger wrote later that, as early as 1868, Henry was one of the first students to win a Pratt prize at P.S. 15.12 Pratt conceived of a curriculum in technical and mechanical training, founding the Pratt Institute in 1887. He died in his office in 1891 on return from lunch, suffering a heart attack while writing a $5,000 check to a charity.

In 1903, Folger was asked to speak at a Pratt Institute ceremony honoring the founder. He invoked Charles Pratt’s personal motto: “The giving which counts is the giving of one’s self.” Folger, who agreed with the motto, continued, “In business Charles Pratt was the soul of honor. Shrewd, sagacious, far-sighted—but the trait which helped him most was trustfulness … he coupled thrift with sagacity, industry with patience. Yes, he was an untiring worker. Wealth came naturally to such a combination of traits.”13 With the utmost respect for Pratt as an educational visionary and innovator, an early leader in the petroleum industry who turned his business achievement into philanthropy, and a mentor who took a personal interest in him, Henry studied Pratt’s path and followed it all his life.

During his years at Adelphi between 1873 and 1875, Folger studied under Homer Baxter Sprague. In 1870, Sprague had come out of journalism to direct Adelphi Academy, but he also taught Greek, Latin, rhetoric, and English literature. Sprague’s ferocious anti-slavery views had led to confrontations with slaveholders and even a Civil War general. Known as a fearless Union soldier, he survived months in Confederate prisons. After five years at Adelphi, he became president of the University of North Dakota and, in 1902, published in the Yale Law Journal “Shakespeare’s Alleged Blunders in Legal Terminology.” No one knows for sure whether Henry Folger heard Homer Sprague discuss William Shakespeare, but chances are he did.

At Adelphi, Henry was one of 550 pupils, girls and boys, divided among three departments: preparatory, academic, and collegiate. His activities included chapel, art, chemistry, and recitation, with a heavy dose of classics. In neatly penned compositions Henry addressed the characters of Caesar and Virgil, a Roman camp, Greek and Latin language and literature. He wrote a current events paper on the press and another on his journey to the top of the pier of the East River Bridge. Folger was chosen president of the literary association at Adelphi, a harbinger of his later mission.

In a graduating class of twenty-two, Folger ranked in the top five. He gave the salutatory oration at Adelphi’s June 1875 commencement. That oration, “Every man is the architect of his own fortune,” held prophetic metaphors. He declared in institution-building rhetoric that everyone has a life-work, a mission:

On observing the lives and characters, not only of illustrious men, but also of those belonging to the lower and common classes, there is perhaps no better simile for the course of human existence, than the comparison of it to the rearing of a building, whose foundations are laid in early youth, and the loftiness and grandeur of whose completed structure depend upon the architect’s abilities and intentions … It is for us to decide, whether our characters shall be grand and lofty structures, or groveling hovels; whether, at death, we shall leave them lasting monuments of imperishable marble, or the mouldering remains of abandoned ruins.14

At eighteen, Folger eerily presaged his own lifework’s culmination in a great marble monument devoted to literature.

Amherst, Massachusetts, east of the Berkshires and the Connecticut River, is surrounded by farmland even today. The Pioneer Valley is best known for tobacco fields that produced one of the finest cigar wrappers in the world; it is home to four colleges and a state university. Amherst College was founded in 1821 “for the classical education of indigent young men of piety and talents for the Christian Ministry.” Today, a coed Amherst has 1,700 students; in Henry’s time, it was more like an advanced academy of several hundred men. During their senior year at Adelphi, Henry Folger and his pal Charlie Pratt visited the college with alumnus William Clark Peckham, an Adelphi science teacher. Unlike Henry, Charlie was wealthy. But both boys were part of a post–Civil War generation for whom a college education was quickly becoming a prerequisite of success. After their campus visit, they told their fathers Amherst was for them. Henry Sr. agreed. Charles Sr. may have preferred Harvard but let his son choose.

Amherst, Massachusetts, east of the Berkshires and the Connecticut River, is surrounded by farmland even today. The Pioneer Valley is best known for tobacco fields that produced one of the finest cigar wrappers in the world; it is home to four colleges and a state university. Amherst College was founded in 1821 “for the classical education of indigent young men of piety and talents for the Christian Ministry.” Today, a coed Amherst has 1,700 students; in Henry’s time, it was more like an advanced academy of several hundred men. During their senior year at Adelphi, Henry Folger and his pal Charlie Pratt visited the college with alumnus William Clark Peckham, an Adelphi science teacher. Unlike Henry, Charlie was wealthy. But both boys were part of a post–Civil War generation for whom a college education was quickly becoming a prerequisite of success. After their campus visit, they told their fathers Amherst was for them. Henry Sr. agreed. Charles Sr. may have preferred Harvard but let his son choose.

Henry Folger arrived at Amherst in September 1875 with the proverbial ten dollars in his pocket. During his first year, he neatly penned over two dozen letters to his parents in Brooklyn; curiously, however, no letter was addressed to both. To his mother he described homework and campus activities; his father heard about money matters. No correspondence from the parents has survived. Henry opened his letters with “My dear Mother” and “My dear Father.” He often closed with “from your loving son Henry” or “from your aff [affectionate] son Henry.” He wrote in brown ink on both sides of folded blue-lined composition sheets, using a fountain pen. Not one for waste, Folger wrote lengthwise, then filled the page margins. His parents saved the envelopes with their canceled green George Washington three-cent stamps. (Henry and Emily also saved letters in their original envelopes, which remained intact save for a few where Henry passed the postage stamps to his nephew, Edward.)

In his first letters to the Folgers at 476 Adelphi Street from Amherst, 140 miles north, young Folger readily admitted he was homesick but proposed a remedy: “If you and Father write Sundays, and Mary and Will twice a week, I’ll receive a letter every day.”15 Henry was mortified when classmates received mail, but he didn’t. Convinced that letter writing was good compositional practice, he regularly wrote his family on Wednesday and Sunday, apologizing whenever a heavy academic workload threw off this schedule. Henry let his family know how much their letters lifted his spirits: “I received three letters from home this past week, and you can hardly imagine how much more quickly the week passes when I receive a letter or two during the middle of it.”

Henry was far from flush, even monitoring his postage: “I enclose this in a monogram envelope. We like it very much, but each envelope costs a cent and a half, so we don’t use them often.” His father had set the tone, questioning his son’s need for a table in his off-campus “boarding-place” shared with Charlie Pratt. Henry wrote to assure his parents that the table was well used, piled high with books.

The elder Folgers’ suggestions on housekeeping and economy irked Henry, who thought the two boys could handle their own affairs: “We thank you much for your advice about house keeping but consider ourselves quite adept chambermen.” When it came to washing clothes, however, Henry confessed frugality gone awry. He decided to buy a warming-stove to better endure Massachusetts winters. He opted for this after rejecting the expense of shipping a stove from the family in New York; he was sure he could sell the stove later for half the original cost. Henry was also sure he could save money by doing his own laundry. He made a fire, heated water in his wash basin, and managed to burn himself in three places, blistering four fingers:

After wringing the “things” as dry as my fingers, now almost useless, could make them, I laid them on the top of the stove to dry. There were two pairs of stockings, three towels, and a handkerchief, in all twenty-five cents worth of washing saved. I then set out for a skate with a clear conscience, thinking that I had saved a quarter of a dollar, or in other terms was fifty cents richer. After enjoying myself immensely I started towards home, with the idea that … I must still iron those “things.” When I came in the front door I noticed a peculiar odor, and on entering the room it became still more observable. As I crossed the threshold … and looked a little more closely, I found my “things” reduced to cinders, if burnt rags may be honored with that name.16

Another time, without injury, Henry sewed up a pair of pants, ripped in climbing a tree to pick five quarts of chestnuts. Like today’s urban foragers, he also delighted in finding free fresh produce: “We have splendid pears in our yard opposite the window and a slipper brings down just enough for us two.” After giving up the idea of having towels sent from home, Henry bought two towels for thirty-three cents, then asked his mother: “Write how much towels should cost so that I can have the satisfaction of knowing whether I have been cheated.”

Folger adapted well to college life and the bracing New England weather. Exploring the Connecticut River Valley, he thought nothing of the seven-mile walk to Northampton. He reported sleighing with friends, admiring a sunset, staying warm at home, playing whist, and occasionally having a “sing” in the parlor. Leaving Amherst, he thought he would miss singing more than almost anything. An early freeze prompted Folger to wax poetic, “A late November rain freezes and produced iced foliage, each twig supporting pendant icicles, that glistened in the light of the rising sun like so many diamonds.” Although an Amherst fall and spring could be muddy, and the winter well below freezing, the climate invigorated young Folger: “Never in better health in my life, I find this air agrees with me.”

In the 1870s, fraternities at Amherst served as vibrant bonding institutions. Students joined a fraternity house early in their first year, to live there. Like most Adelphi alums, Folger chose Alpha Delta Phi, perhaps because Adelphi professor Peckham had joined it. Henry noted in his college papers that Henry Ward Beecher, class of 1834, who often came to Amherst to preach, belonged to the same fraternity. (Beecher had advocated coeducation at Amherst, as he had at Adelphi, but it took until 1975 to achieve it.) Henry explained that “Freshman River,” where he loved to ice skate, got its name in a bygone era when hazing was in vogue and upperclassmen “ducked” freshmen. As a sophomore, one was allowed to wear a top hat and carry a cane, as Henry’s class photograph shows. Food packages from home offered treats to the fraternity brothers. While Mrs. Folger sent a plum cake, she was outdone by what Henry approvingly called “Pratt’s spread,” featuring Mrs. Charles Pratt’s pickled oysters. Other mothers sent tongue and crackers, jellies and pies, treating the boys to fraternity feasts. Overindulgence was not unknown. “Last night,” Henry confessed to his mother, “I was not as well as I would like to be always. I suppose it was the remnants of our ‘delegation bum’ [class drunk] that was the cause of it. But I laid abed till after ten, ate no breakfast, and now feel as good as new.” Although abstemious in later life, in college Folger was one of the boys.

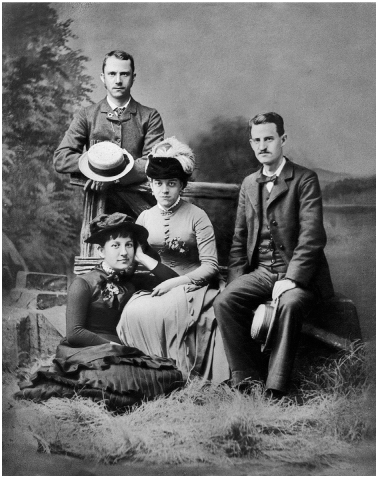

Alpha Delta Phi brothers at Amherst College pose for local photographer J. L. Lovell, 1879. Henry Folger stands top center, to his left, Charles M. Pratt. Sporting canes was a college tradition. Amherst College Archives and Special Collections

Henry shared his daily schedule and a self-assessment of his academic performance. “We usually rise at six, and study till seven fifteen, then we have breakfast. At 7:53 we are due at the chapel, and immediately after have calisthenics, and our first recitation follows directly afterwards.” Henry confirmed taking Greek, passing a Latin exam, and doing well in Geometry. His three daily recitations required eight hours of study or more, and he found history most difficult. He announced to his father that, in order to increase his chances of doing well in recitation, he employed a fraternity brother to drill him, at a dollar an hour. As an upperclassman, Henry himself tutored younger students at Alpha Delta Phi.

Henry was undecided about how much he should care about class rank. Initially he judged himself twelfth of a class of seventy-four, but believed as many as twenty-five peers were more able than he. Henry was more concerned with his self-image: “I feel that I have been faithful to myself in study and I don’t care how I stand.” Learning that he ranked first among classmates from Adelphi Academy, he revised his earlier judgment: “I am more than satisfied with my standing.” After his first year, Henry’s steady stream of letters to his parents ran dry, indicating he felt he had made an adult life for himself. Unfortunately, his parsimony in prose continued, allowing his talent for expression to lie fallow all his life. Henry wrote a few letters home as graduation approached, and tried to console his parents by empathizing with their decision not to make the journey due to the cost.

Henry Folger’s Amherst education was classical. As the college had fashioned a curriculum designed in part to train clergymen, required courses were orthography, elocution, and declamation, as well as exercises in English sentences, rhetoric, and extemporaneous speaking. While physics was mandatory for students headed for a B.S. degree, English literature, political economy, government, and history were marginal electives for all. Like many New England colleges, Amherst evolved into a liberal arts institution of higher learning that sent men into many professions besides the church.

Folger excelled, compiling a four-year average of 89 of 100. A solid achiever, as a freshman he scored 88 and as a senior, 91. Folger’s lowest grade was 85 in Greek. In modern languages—French and German—Henry scored 88. While far from fluent, he would later use his reading knowledge to scour book auction catalogs from many countries. In mathematics, a subject vitally important to people in the oil business, Folger landed a 90 average over four years. He was elected to Phi Beta Kappa in his junior year and graduated fifth in his class. Graduating first in the class was twenty-year-old John Franklin Jameson, who would play a role in where the Folger Library would eventually be located.

The woman who would become Henry’s wife and partner in bibliomania was born Emily Clara Jordan on May 15, 1858, in Ironton, Ohio. The industrial town sat along the Ohio River in the southern tip of the state, drawing its name from assets of iron ore and coal. Her mother was Augusta Woodbury Ricker, born in Bath, New Hampshire. Her father, Edward W. Jordan, came from Moriah, New York. When asked in college to name “other nationalities in your ancestry,” Emily responded with “French Huguenot, Scotch, and English.”17

The woman who would become Henry’s wife and partner in bibliomania was born Emily Clara Jordan on May 15, 1858, in Ironton, Ohio. The industrial town sat along the Ohio River in the southern tip of the state, drawing its name from assets of iron ore and coal. Her mother was Augusta Woodbury Ricker, born in Bath, New Hampshire. Her father, Edward W. Jordan, came from Moriah, New York. When asked in college to name “other nationalities in your ancestry,” Emily responded with “French Huguenot, Scotch, and English.”17

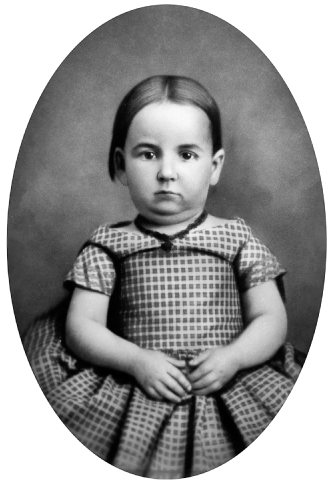

The youngest of three sisters, as a child Emily Clara Jordan moved from Ironton, Ohio, to Washington, DC, to Flushing, New York, to Elizabeth, New Jersey, ca. 1862. By permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library

A lawyer and newspaper editor, Edward Jordan campaigned to elect Abraham Lincoln president. Lincoln responded by giving “Jerdan,” as he called him, a commission as Solicitor of the Treasury, where he stayed until the end of the Andrew Johnson administration. In Washington, where the Jordans lived on the corner of 12th and M Streets during the Civil War, Edward once took young Emily to meet President Lincoln in the White House. She was so moved by the encounter that she wrote a short story about it, scribbling in pencil in her 1908 diary a tale, “The President and the Little Girl.” Her (unpublished) story reveals a child’s sensitivity to pain and suffering during the Civil War. The little girl’s request to the president was simple: “I want one wounded soldier on the battlefield taken care of.” “Father Abraham’s” reply was, “I do, too.”18

With her sisters, Mary Augusta and Elizabeth, Emily went to Miss Ranney’s School on 211 S. Broad Street in Elizabeth, New Jersey, after the family relocated. From 1861 to 1881, Nancy D. Ranney prepared women for teaching or further study. Brother Francis would read law. From their parents—neither of whom had gone to college—the Jordan children inherited “an enlightened mind, a sense of humor, and a critical love of books.”19

Eighty-five miles west of Amherst, in the old river port of Poughkeepsie, New York, in 1861, English immigrant and retired beer-brewer Matthew Vassar, prompted by a bright niece’s desire for education, founded a collegiate institution for women on the grounds of an old racetrack several miles from his estate at “Springside.” The college’s first (and only) building for a time, stately Main Hall, was designed in the French mansard-roof style and built near the center of the thousand-acre campus. Unusual for a businessman of his time, and allying himself with Reverend Henry Ward Beecher, Vassar declared boldly that “woman, having received from her Creator the same intellectual constitution as man, has the same right as man to intellectual culture and development.”20 Advocating that women, whenever possible, serve on the college faculty and administration, Matthew Vassar announced at the first meeting of the college trustees that “the course of study should embrace English language and its literature, other modern languages, mathematics, natural science, intellectual philosophy, political economy, and moral science.” His college would be no “finishing school.”

Eighty-five miles west of Amherst, in the old river port of Poughkeepsie, New York, in 1861, English immigrant and retired beer-brewer Matthew Vassar, prompted by a bright niece’s desire for education, founded a collegiate institution for women on the grounds of an old racetrack several miles from his estate at “Springside.” The college’s first (and only) building for a time, stately Main Hall, was designed in the French mansard-roof style and built near the center of the thousand-acre campus. Unusual for a businessman of his time, and allying himself with Reverend Henry Ward Beecher, Vassar declared boldly that “woman, having received from her Creator the same intellectual constitution as man, has the same right as man to intellectual culture and development.”20 Advocating that women, whenever possible, serve on the college faculty and administration, Matthew Vassar announced at the first meeting of the college trustees that “the course of study should embrace English language and its literature, other modern languages, mathematics, natural science, intellectual philosophy, political economy, and moral science.” His college would be no “finishing school.”

Ever since the Revolutionary War, pioneering New England teachers such as Sarah Pierce in Litchfield, Connecticut; Catherine Beecher in Hartford; and Emma Willard in Troy, New York, had sought to train women in academic as well as “domestic sciences” and decorative arts. The women who graduated from these schools, they insisted, would be partners to the second generation of Founding Fathers. They—and their daughters after them—would need, in order to be good Mothers of the Republic, more formal education than had been available to Abigail Adams, Martha Washington, or Dolly Madison.

This curriculum at Vassar, the first large endowed women’s college in America, differed from its classical counterpart at men’s institutions. While Latin and mathematics were required of all freshmen, French replaced Greek. Mental and moral philosophy were mandatory in the second and third years. Matthew Vassar was a devout Baptist who assured that theology and Christian studies entered the curriculum. Only unmarried women were allowed to teach in women’s colleges. Vassar did not teach domestic economy, judging that students could obtain these skills at home. English literature and expression were offered, but no history until 1887. Like other women’s colleges at the time, Vassar tried to provide a useful education that could lead to a profession; science was privileged. Offered opportunity for serious study, college women of the first generation—the 1860s through 1880s—were expected to pursue it conscientiously. In 1870, 11,000 women attended college in America, compared to about 41,000 men. The total population of the country at the time was about 38 million.

The three Jordan sisters thrived in this rich environment. Mary Augusta Jordan entered Vassar as a freshman in 1872. Her younger sisters, Emily and Elizabeth, followed in 1875. The two proudly saw their older sister graduate in June 1876, then stay on as college librarian, validating one of Matthew Vassar’s goals. In this family of modest means, Mary Augusta was able partly to finance her younger sisters’ studies. Emily was chosen president of her class of thirty-six—an honor that lasted a lifetime. Winning a Phi Beta Kappa key, as did Mary Augusta, Emily’s best subjects were English composition, French, and astronomy. Close behind ranked botany, chemistry, math, and English criticism. Academic proficiency in both science and letters prepared Emily well for her later roles as teacher in a Brooklyn secondary school and, eventually, as life partner of a business executive with wide-ranging literary interests.

A worn green buckram-covered volume with the words “Scrap Book” embossed in gold letters contains mementoes of Emily’s college days. Interspersed with pressed leaves and flower petals lie souvenirs of her academic, cultural, and social life from seventeen to twenty-three.21 The scrapbook contains several items about Maria Mitchell, the country’s first woman astronomer and the first professor hired when Vassar opened in 1865. Despite criticism, Professor Mitchell encouraged scores of students through the 1880s to prepare for scholarly careers. Emily and her classmates keenly admired Mitchell as an intellectual role model. Emily saved several pictures of Saturn’s rings from her classwork and, a real treasure, a booklet, Notes on the Satellites of Saturn, from her favorite professor, inscribed: “Miss Jordan, with love from Maria Mitchell.”

Each year’s astronomy class culminated in a “dome-party.” Dressed in their finest, students would file up the stairs into the observatory dome a few hundred yards from Main Hall—boasting the third most powerful telescope in the country—for a breakfast party celebrating science and literature. Tables were set in a circle, at each place a name card, a rosebud, and a small photo of the observatory. Silver-haired Professor Mitchell, in plain Quaker dress, presided. After chicken croquettes followed by strawberries, came poetry. Each student drew a neatly folded paper from a large basket the professor ceremoniously circulated. The notes contained poems, many of which made scientific allusions, and most of which Maria Mitchell herself handwrote in block letters. The students went around the circle, reading aloud to general merriment:

With my views it’s according

to prize highly Miss Jordan;

Few are richer & rarer

Than Emily Clara,

her head is clear and her logic the same,

But when it comes to rhyming

I don’t like her name.

Many messages concentrated on a student’s personal traits. Here lies a rare glimpse of how a professor viewed young Emily as a clear, logical thinker. (Would her mental sharpness remind her future husband of a Portia, a Beatrice, a Rosalind, or a Viola?) The evening ended with the girls forming an impromptu choir on the movable observatory steps to sing popular melodies. This grande dame of the dome endeared herself to scores of Vassar students. Born in a Quaker family in Nantucket, Maria Mitchell was a descendant of Peter Foulger. When Professor Mitchell died, Emily took charge of ensuring part of the noted astronomer’s legacy. Mitchell’s ambition had been to render her department independent and self-supporting. Emily assumed the chair of the Maria Mitchell Endowment Fund and organized pledge drives, proudly announcing to donors that the money invested was earning eight percent.

Besides receiving written invitations from faculty to parlor teas, coffees, or desserts, Emily joined class outings. A leaf of sorrel became a memento of a ride with Julia, and a forget-me-not of an excursion with K. S. Hawley. Students would send cards to special friends with “compliments” to each other. They circulated affectionate poems and sent flowers or other gifts. Such ritualistic demonstrations of fondness among students, and sometimes with faculty, were called “smashing.”

The college looked toward a class president for special duties. Members of the faculty wrote notes to Emily, asking her to contact the whole class on matters such as canceled classes or lists of students who would be traveling at Christmas. Emily often presided over the dinner table, occasionally inviting her older sister to sit with her.

Vassar offered many opportunities for cultural enrichment and social interaction, the latter with chaperones. Classmate Sophia Richardson, secretary of the Shakespeare Club, “cordially invites Miss Jordan” to become a member on September 28, 1876. We can assume she joined. Emily put much energy into the Philalethean Society, a cultural organization. The society produced plays, including George Eliot’s Spanish Gypsy, planned “literary entertainments,” organized debates, and sponsored concerts. Emily’s fervor for the Philalethean put her on the organizing committee in senior year. In a Thanksgiving musical performance, Emily played the triangle. On stage she took the role of Fanny in Everybody’s Friend, a three-act comedy. Poughkeepsie has an Opera House, the Bardavon, which Emily frequented; like Henry, she saved her concert and theater ticket stubs. Three years after graduation, she returned to campus to address the Philalethean Society in the chapel. Emily was the rare recent graduate to display so much dedication to her alma mater and keep in such close touch with fellow students. With similar Jordan enthusiasm, her sister Mary Augusta became secretary of the Vassar College Alumnae Association.

At a period when many young women did not know how to dance, Emily went to class “sociables,” “hops,” and lancier and quadrille dances with West Pointers twenty miles down the Hudson River. With other Vassar young ladies, she made the voyage via carriage, train, and then ferry. A pressed leaf from May 1877 and pressed grass in February 1878 bear small white labels with the initials L. J. Emily, however, did not have her heart and mind set on a cadet. She kept handy the New York Central and Hudson River Railroad timetable, traveling home for vacations with one trunk from room #26 at Main Hall by taking the 6:30 A.M. “Mary Powell,” the side-wheeler steamboat known as the Queen of the River, for New York.

Five commencement programs from 1876 to 1880 list the girls Emily would have lived, laughed, dined, studied, and talked with at Vassar. Two were the daughters of suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton: Margaret (class of 1876) and Harriot (class of 1878). For all its liberal views, Vassar did not go so far as to invite their firebrand mother to lecture on campus while they were students. Nevertheless, Ms. Stanton managed to meet informally with student groups to spread the gospel of women’s rights. Activism in voting rights followed apace behind more open opportunities in women’s higher education.

On commencement day at Vassar—June 25, 1879—the same day Henry Folger graduated from Amherst, Emily’s classmates said goodbye.

Miss Jordan, as President of the class of ’79, you, like the rest of us, are soon to leave “Alma mater”; but your connection with us is not to be severed. You, who have led us through this, our last year, will still be at our head. It may be that we shall never meet again as an unbroken class, but we trust that those who are permitted to attend our reunions may always find you ready to fill the President’s chair. As an emblem of what you have been, are, and will be, we present you with this ruler, hoping you may have many occasions for exercising your mild sway over us.

Emily was about to enter the world of work, buoyed by expressions of confidence from the faculty and students. She was a leader, very effective without wielding a big stick.

Pleased with her college mementos, Emily assembled a second scrapbook containing programs, invitations, and notes covering her six years of teaching in the Nassau Institute in Brooklyn, where she was hired right out of Vassar. The boarding school sat on the corner of Classon and Quincy Streets, within walking distance of Emily’s home. Started in 1868 by two sisters named Hotchkiss, the school prided itself on thoroughly training young ladies under the vigilant eye of a nearby Presbyterian Church. Educational principles included character development, ethics, and physical culture. Busier now, and less concerned with neat presentation than with saving fugitive documents, Emily was more likely to insert material in her scrapbook between pages than to use paste. Among the twenty questions in the literature/history tests she devised to keep her pupils on their toes were: “Where does Longfellow live? For what is the town celebrated? Who went to France for his struggling countrymen?” In rhetoric, “What are the elements of discourse? What is the use of the ‘a priori’ argument?” The young teacher stressed factual knowledge. Emily wrote an essay on printing and Gutenberg, perhaps as a model for her students. To help prepare for classes, she frequented the Brooklyn Library reading rooms on Montague Street in Brooklyn Heights.

Emily received many Tiffany-engraved invitations to receptions and soirées, teas and weddings. She traveled to New Jersey to hear the Princeton College Glee and Instrumental Clubs. She saved a program of HMS Pinafore by Gilbert and Sullivan. Christmas and New Year greetings arrived printed on small business cards. Emily participated in several religious organizations, one a Brooklyn “Sunday-School Union,” with singing, scripture readings, prayer, address, and benediction. She attended a painting and statuary exhibit in the Presbyterian Church of Elizabeth, New Jersey. Taking a rare break, Emily went to Brighton Beach on Coney Island. She took home a verification of her “Correct Weight” of 133 pounds and a Brighton Beach concert program advertising “Waterproof linen cuffs, collars and bosoms perspiration proof.”

Similarly, Henry recorded his Amherst career in a violet cloth-covered scrapbook whose stiff green pages covered all four undergraduate years and mainly featured academic programs, athletic contests, cultural events, extracurricular activities—mostly choral performances—and fraternity dinners.22 In contrast to Emily’s generous pagination, almost all of Henry’s mementos were neatly pasted, leaving almost no margins. No waste.

Similarly, Henry recorded his Amherst career in a violet cloth-covered scrapbook whose stiff green pages covered all four undergraduate years and mainly featured academic programs, athletic contests, cultural events, extracurricular activities—mostly choral performances—and fraternity dinners.22 In contrast to Emily’s generous pagination, almost all of Henry’s mementos were neatly pasted, leaving almost no margins. No waste.

The first loose sheet, surprisingly, consists of vital statistics the college collected on all incoming freshmen. (Amazingly, these albums of freshman physical statistics continued at many Eastern colleges, including Vassar, into the mid-twentieth century.) Folger, at eighteen, stood five feet four and weighed only 110 lbs. The shoe size of this slight, left-handed man was seven. An Amherst fraternity mate referred to him as “little Folger.” While only five feet tall herself, Emily also remarked occasionally on Henry’s slight stature. Later on, Henry grew first a mustache then a beard—perhaps due to his underbite, perhaps trying for additional gravitas, perhaps both. His grandnieces—some with the hereditary underbite—believe that Emily was behind these changes.

Henry’s admitted lack of athletic prowess (though in middle age he would take up golf and play quite well, being an ace on the putting green and entering senior competitions) did not translate to athletic indifference. He pasted into his memory book ticket stubs from Amherst’s football games against Brown and Yale. He not only attended games and meets; he minutely recorded in program margins the competitor’s class, distance, times, and scores. In an athletic association program from his sophomore year, he entered times for a half-mile run, a 100-yard dash, and lengths and heights for jumping events.

Henry was always attracted to winning. He noted the highest achievements in a field even if they were not his own. His notes also reflect the meticulous record-keeping that would flower in his collecting mania. Later, Henry closely followed the market price for thousands of volumes in bookstores and at auction, even when he was not the bidder.

Folger’s scrapbook conveys the flavor of his academic life. He saved the Latin, Greek, and English grammar exam booklets from his Amherst admissions. He kept an 1876 rhetoric exam and one in French from 1877. He noted two subjects—declamation and recitation—with his grades over four years. At least once a year, Henry received the top grade of 100 in both subjects. His lowest term grade in recitation was 86; in declamation, 98. Seniors at Amherst took recitation two or three times a week and declamation once.

Shakespeare commanded an unassailable place in recitation. Folger saved his essays on the characters of Shylock, Portia, and Macbeth. He found Shylock a “wonderful example of the power and scope in dramatic art” that “makes our blood tingle.” His professor wrote in the margin, “Apart from the matter of clearness, and facility in the use of language, you need to pay especial attention to smoothness of style; since, though graphic, you are sometimes abrupt.”23 After Folger characterized Portia as womanly, intellectual, attracted by pure motives, and buoyant of spirit, the professor penciled in the margin, “The style is good, but more grace and beauty must be added.” He made no more corrections on Folger’s essay on Macbeth. Folger’s class may have been one of the first at Amherst to study Shakespeare’s plays. Folger’s friend George A. Plimpton wrote that Amherst professors lectured on Shakespeare the writer without reading his plays.24

With tongue in cheek, alluding to a Shakespearean line, Folger wrote above his grades, “O, my offense is rank it smells to heaven.” He seems unsatisfied with less than being the best in academic competition. Another list, signed “Folger” at the bottom, indicates his partial readings in English literature while at Amherst: Bacon, Jonson, Marlowe, Massinger, Dryden, Addison, Pope, and Milton. Later, Folger would collect their first editions and, in some cases, manuscripts and autograph letters as well.

In Folger’s day, Amherst students enthusiastically competed for annual prizes sponsored by college icons named Kellogg, Hardy, and Hyde. Amherst awarded first, second, and third cash prizes for the best essays read publicly by the authors. Oratorical contests became popular, prestigious college events, with orchestral preludes and postludes. Henry’s scrapbook holds tickets and programs for these competitions. A clipping from the Brooklyn Eagle reported that local boy Folger was chosen to compete for the Kellogg Prize. His name figured among the winners of the Kellogg in 1876 for his essay, “Pericles before the Aeropagus.” He pocketed $100 with the Hyde in 1879 for a first-prize paper on Tennyson.

That may not sound like an enormous sum today. Then, it paid for a whole year’s tuition at Amherst. Henry’s oratorical prowess was a godsend to the money-strapped Folgers, who lacked the funds to visit their eldest at college, even for commencement. The same year, Folger competed for the Hardy Prize on the theme “Has a college course of study a tendency to repress independence of thought?” The Amherst Student reported that Folger won the First Junior Prize with an essay on “Dickens as a preacher.”25 Folger saw the competitions as opportunities to excel and further hone his speaking skills. His model was Daniel Webster, whose oratorical style he dissected in an essay.

Henry Folger sang a solid bass-baritone in the Amherst College Glee Club. The club sang often at Amherst, elsewhere in the Connecticut Valley, and, on occasion, in more distant locations. Henry saved the ticket for the Boston & Albany railroad trip that took the Glee Club to perform for the first time in Boston. In early 1879 he traveled with the Glee Club to Brooklyn to sing a benefit concert at the Academy of Music to support his alma mater, Adelphi. In his senior year, Amherst mounted one of the early (most likely pirated) American performances of HMS Pinafore. Henry played a major role as Dick Deadeye. His scrapbook contains a sheet of music on which he wrote the notes and lyrics he had to learn. The local Amherst newspaper reported, “Folger was a superb Deadeye. His part throughout was a great hit.” Someone commented on how surprising it was to hear such a loud, deep voice emanate from such a slight man. When Emily later learned of his success in the role, she began affectionately to call him “Dick.”

Folger’s scrapbook contains a tuition bill, signed by the college treasurer, William Austin Dickinson, the poet Emily’s older brother. Folger, who later paid a small fortune for manuscripts and famous Elizabethan signatures, would have been amused to learn that recently on eBay a vintage Amherst tuition bill was for sale at ninety-five dollars, due to the Dickinson connection. He would have been incredulous to learn that another Web site peddling historical documents offered for $5,000 a certificate of “100 shares of the Standard Oil Trust” made out to Henry C. Folger Jr. and signed by John D. Rockefeller.

Although nothing in his scrapbook suggests that Folger was following Amherst College’s earlier path toward Christian ministry, Folger clearly felt a spiritual dimension. He saved invitations to prayer meetings. He also kept tickets to lectures by the American evangelist Joseph Cook, who influenced many students when he spoke on the importance of Christianity for men and nations. With more than a dozen classmates, Henry was baptized at the college church in May 1876. Calvin Stowe, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s husband, performed the rites. Religious seeds sowed at Amherst encouraged Henry to become a lifelong active Congregationalist.

At commencement, Folger feasted at class suppers and engaged in musical and speaking events that marked this rite of passage. “Class Day” was a solemn occasion for odes and orations, a milieu in which Folger flourished, and he was chosen to deliver the coveted Ivy Oration. It is perhaps no surprise that the scrapbook of such a dutiful, self-contained young man contains almost no mention of social life. One of the last items in Henry’s scrapbook was marked “Senior Promenade.” Twenty slots were available for partners’ names on the prom dance card, but Henry’s card was blank. A lone dried leaf is affixed to one page, vestige perhaps of some undisclosed walk in the woods or brief whimsy. Emily and Henry’s college scrapbooks—preserving what each valued—were parallel tracks to a common destiny, though Miss Jordan was the more social one.

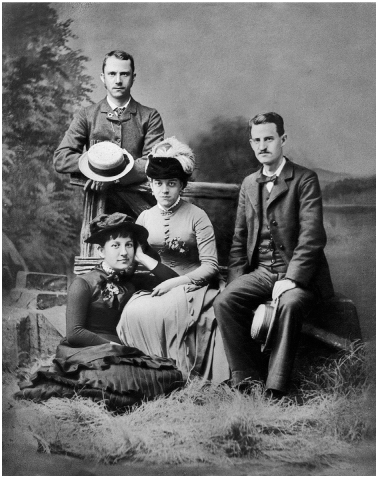

Rain poured down on October 6, 1885, as Emily and Henry were wed in the Westminster Presbyterian Church in Elizabeth, New Jersey. Mr. Jordan gave away his daughter, whom six bridesmaids, with Lillie Pratt as maid of honor, preceded to the altar. Two weeks after their wedding, a British Sunday newspaper published an article titled “The Mystery of an Autograph.” The article about an autograph of William Shakespeare came to the attention of the Folgers, and the couple’s Shakespeare collection was under way.

Rain poured down on October 6, 1885, as Emily and Henry were wed in the Westminster Presbyterian Church in Elizabeth, New Jersey. Mr. Jordan gave away his daughter, whom six bridesmaids, with Lillie Pratt as maid of honor, preceded to the altar. Two weeks after their wedding, a British Sunday newspaper published an article titled “The Mystery of an Autograph.” The article about an autograph of William Shakespeare came to the attention of the Folgers, and the couple’s Shakespeare collection was under way.

The Folgers shared a home with Henry’s parents at the modest 72 Quincy Avenue, Brooklyn, before they rented their first house in 1895 at 212 Lefferts Place in Bedford-Stuyvesant. In 1910, they moved around the corner to rent a large six-story brownstone at 24 Brevoort Place. In 1929, after Henry retired from Standard Oil, they bought their first home at 11 Andrews Lane on the edge of the exclusive North Shore enclave of Glen Cove, Long Island. After her marriage, Emily stopped teaching at Nassau Institute but continued to lead Sunday school classes at the Plymouth Church in Brooklyn Heights.

Henry and Emily exchanged no love letters that we know of, yet after the wedding, they were inseparable. When Henry took the rare business trip, he sent laconic postcards to “EJF” from “HCF.” From Abilene, Texas, in November 1910, one message—longer than most of Henry’s missives—read “All in fine health and spirits.”

As the couple pursued collecting Shakespeare, on several occasions Henry carefully respected Emily’s preferences. He wrote a dealer, “Will you please have sent to my house in Brooklyn, 24 Brevoort Place, the Shakespeare bronze about which you saw me the other day? I will take it, provided, without fail, you send the one which Mrs. Folger saw.” Writing another dealer, he made sure not to slight Emily’s own choice: “My wife, when we were abroad last Summer, made quite an elaborate collection of similar souvenirs and she will not understand why I think it worth while to supplement what she has done, so I return it herewith.”26

Folger’s most assiduous bookseller, Dr. A. S. W. Rosenbach from Philadelphia, often saw the Folgers together: “She would hunt up bibliographical details and investigate difficult allusions, and frequently she would advise him to purchase a book or manuscript when he was wavering and undecided. It was a very rare and beautiful thing, this complete harmony with a husband’s hobby, and I know of no more perfect example of it.”27

Henry Folger always credited his wife. In a letter to book dealer John Howell he wrote:

Mrs. Folger is quite an expert on Lincoln autographs, her father having been an official in Washington under Lincoln, she having a number of autographs, and she questions the authenticity of the signature in the volume of Shakespeare. I told her I thought you had a history of the volume to show the ownership from Lincoln down to the present time. If so, can you reassure us on the subject? Lincoln read Shakespeare, but, according to his own statement, specialized in Macbeth. As it happens, this play in your volume shows no indication of ever having been studied; it is one of the freshest plays in the book.28

Folger must have been pleased to present his wife as an expert, and, adding his own clever sleuthing, used her expertise to back Howell against a wall.

The Folgers were a couple that, for the most part, saw things the same way and delighted in looking in the same direction. But not always. In August 1910, Emily accompanied Henry on Standard Oil business to Paris. Like royal visitors, they stayed in the posh Hotel Meurice on the Rue de Rivoli overlooking the Tuileries. Like an ordinary tourist, Emily admired the Louvre’s Winged Victory and Venus de Milo. She noted in her trip diary that her husband liked Notre Dame, but not as much as Westminster Abbey. While Henry found the French capital “dirty and disappointing,” Emily “loved it.”29

Emily’s address book showed a woman prepared for all eventualities on their European jaunt, but especially for a grand spree. Yes, if it came to that, she knew where to find a watch repairman, druggist, and three doctors. Four addresses showed where she could have her hair done with Parisian flair, seven offered the latest fashions in ladies’ hats, no fewer than fourteen listed pâtisseries, and twenty-one were tempting dress shops.30

A Christmas poem for “Dick” sweetly manifests Emily’s playfulness and awareness of Henry’s frugality despite a solid marital bond:

Dear Santa says he brought my man a fur coat

But on my life as I’m his wife, I’d not, sir, know’t

’twas 1907

Exactly when Santa financed it.

He says I’ll one day see a coat and picture,

Our joy and love continuing without mixture,

For 1908

Towards your portrait

His throne has chanced it.31

It seemed to Horace Howard Furness, Shakespearean scholar and editor and Emily’s mentor for her master’s thesis at Vassar, that the couple was perfectly suited to each other by common literary and scholarly tastes. “My dear Emily,” he wrote, “thank you heartily for all your kind words. It is always a source of continual pleasure to me to reflect that there are in this world two such happy people as you and Henry, who can read and study side by side.” Furness wittily addresses them: “Dear HenryandEmily (man and wife are one, and should not be separated even by hyphens).”32 Charlie Pratt, Henry’s boyhood chum, college roommate, and Standard Oil colleague, knew the Folger couple better than most: “I find much comfort in thinking of you, Emily and the steady unchanging philosophy of life which each of you has never varied since I first knew you.”33 He spoke for others in recognizing the constancy and reliability of the Folgers’ “marriage of true minds” after thirty-five years together.

Newlyweds Charles (standing) and Mary Pratt and Henry and Emily (in brimmed black hat) Folger, 1885. Two Amherst-Vassar weddings were the prelude for lifelong friendships, and fortunes, thanks to a common employer, Standard Oil. By permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library

Other measures of Henry’s affection and concern for his wife appeared as they aged. Henry cared for Emily’s state of health as much as for his own. While he hated to decline an invitation to see a New Haven performance of King Lear, he wrote a friend, “I must now give our personal health first consideration, for a time at least. I am afraid the trip might prove too fatiguing for one or both of us.” Every spring from 1914 until 1929 a chauffeur drove them in the family Lincoln to the Homestead in Hot Springs, Virginia. Emily would take medical baths ordered by her doctor, use the pool, and go to the hairdresser. Henry golfed with his friends. Rosenbach would often try to tempt Folger to stop off at his Philadelphia bookshop en route to or from Virginia, but Folger had clear priorities: “I cannot leave Mrs. Folger here alone. She is taking the cure.” Ever the quietly attentive husband, Henry arranged for flowers to be delivered to their room. Henry selected gifts for Emily that he knew pleased her: necklaces of pearl and onyx, a cameo and a carnelian brooch, a diamond watch bracelet. He bought her silver from Tiffany’s and Gorham’s. If his choice did not please her, as in the case of some rings, he returned them.

A rare family recollection of the couple has survived in the responses to a questionnaire composed in the late 1970s by Folger Library docent Elizabeth Griffith. Folger Library director O. B. Hardison had urged Griffith to obtain direct family recollections with a view to producing a short biography of Emily. (Unfortunately, the project ended in its early stages.) Emily’s nephew and close adviser Judge Edward J. Dimock told Griffith that the marriage was affectionate and happy; he could recall “no hint of a single quarrel, disagreement or misunderstanding.” The judge considered that Henry was “completely dominant” but that Emily “submerged herself to his life and interests and appeared to be completely happy to do so. She gave herself ungrudgingly.” Dimock believed that his aunt’s “sweetness and generosity of spirit were remarkable and utterly genuine.” He never heard any comment on the Folgers’ childlessness or any reports of a miscarriage or a stillbirth. He believed that “building the collection and planning the monument to house it was totally absorbing, a real substitute for children.”34

James Waldo Fawcett, journalist at the Washington Evening Star, often covered the Folgers and their library. Emily hired him to write Henry’s biography; they got as far as assembling lists, notes, an outline, and considering Houghton Mifflin as the preferred publisher. Regrettably, after Mrs. Folger’s death, Fawcett abandoned the project, which he had seen as a love story, writing, “The Library itself … is the enduring fruition of the romance of Henry and Emily Folger. It is a living proof of the eternal values of work and love.” Elsewhere in the article Fawcett called the story of the foundation “an authentic romance without recorded parallel in the history of American philanthropic idealism.”35

Touchingly, for such a reserved man, Henry Folger showed his enduring faith in Emily in a singular notarized document: “I hereby give to my wife, Emily C. J. Folger, all my books, autographs, pictures, prints and other literary property, being largely Shakespeareana, to be her own to use and dispose of as she may see fit; the same being absolutely free from all debt or incumbrance of any nature whatsoever.”36 Emily Folger was a bluestocking, an educated, intellectual woman with a scholarly bent. More than Henry’s life partner, she was his intellectual soulmate. Theirs was a happy marriage that bore unbelievable fruit.

Henry’s blue-eyed ancestors had little interest in literature. Enterprise and business acumen distinguished the Folgers, who had lived on Nantucket Island off the Massachusetts coast for three hundred years and continue there today. Blacksmiths, carpenters, and seamen, they supported the bustling whaling trade. They were too busy to collect scrimshaw, decorated quarterboards, or barrel staves. Of Flemish descent, Peter Folger (originally spelled Foulger)—the first and most colorful of the island’s Folger clan—was born in Norwich, England, in 1617. He sailed with his parents to Massachusetts in the late 1620s. On Nantucket, he apprenticed for many trades: surveyor and blacksmith, miller and joiner, court clerk and recorder, school teacher and missionary. Adept in languages, he learned the Algonquian tongue of the Wampanoags. Practical, he fabricated and used machinery. Literary, he wrote poetry. Peter was a baptized Congregationalist who became a Baptist and showed sympathy with Quakers. Folger’s last child with Mary Morrel was a daughter, Abiah, born in 1667. Abiah became the second wife of Boston soap maker Josiah Franklin, and at age forty-one she gave birth to Benjamin Franklin. In homage to this distant connection, Henry Folger maintained that had he not collected Shakespeareana, he would have collected Frankliniana.3

Henry’s blue-eyed ancestors had little interest in literature. Enterprise and business acumen distinguished the Folgers, who had lived on Nantucket Island off the Massachusetts coast for three hundred years and continue there today. Blacksmiths, carpenters, and seamen, they supported the bustling whaling trade. They were too busy to collect scrimshaw, decorated quarterboards, or barrel staves. Of Flemish descent, Peter Folger (originally spelled Foulger)—the first and most colorful of the island’s Folger clan—was born in Norwich, England, in 1617. He sailed with his parents to Massachusetts in the late 1620s. On Nantucket, he apprenticed for many trades: surveyor and blacksmith, miller and joiner, court clerk and recorder, school teacher and missionary. Adept in languages, he learned the Algonquian tongue of the Wampanoags. Practical, he fabricated and used machinery. Literary, he wrote poetry. Peter was a baptized Congregationalist who became a Baptist and showed sympathy with Quakers. Folger’s last child with Mary Morrel was a daughter, Abiah, born in 1667. Abiah became the second wife of Boston soap maker Josiah Franklin, and at age forty-one she gave birth to Benjamin Franklin. In homage to this distant connection, Henry Folger maintained that had he not collected Shakespeareana, he would have collected Frankliniana.3