The ACU, the organizing body for the TT meeting, had seen the number of entries for the races grow each year from their first running in 1907, and by 1911 it was confident that it operated from a position of strength and could shape the event in the manner of its choice. Showing considerable vision, despite opposition from manufacturers and riders, it moved the races from the relatively flat St John’s Course to a distinctly more testing one that gave a lap distance of just over 37 miles (60km) and incorporated a 1,400ft (425m) climb from sea level to skirt the northern flank of Snaefell. The adoption of what quickly became known as the Mountain Course was a move that, according to Motor Cycle some years later, ‘drove the whole motorcycle industry to develop engines of greater flexibility and to equip them with reliable and efficient variable gears’.

On the approach to the 1911 TT, manufacturers worried about how their existing big single- and multi-cylinder machines would cope with the demanding new Mountain Course, but the ACU had no such concerns and showed it by creating an additional race for singles up to 300cc and multis up to 340cc (resisting manufacturers’ calls for these smaller machines to be allowed pedalling gear). Thus two separate races were run in 1911 on different days and they were given the titles of ‘Junior’ (run over four laps) and ‘Senior’ (five laps). They attracted 104 entries, with the split between the classes showing thirty-seven Junior and sixty-seven Senior runners. Entry fees were double those of the first TT in 1907, being a substantial 10 guineas for trade and 7 guineas for private runners. In a further attempt to even out the performance differential between singles and multis in the Senior race, the capacity limit of multis (generally twins) was reduced from 670 to 585cc.

Manufacturers had received a foretaste of the demands that the climb of Snaefell would make on their machines when, just after the 1909 and 1910 TTs, the ACU ran a 6-mile (9.6km) hill climb from the sea-level outskirts of Ramsey to almost the highest point on the Mountain Road at the Bungalow Hotel. Several firms experimented thereafter with variable gears, and on machines that adopted them for use in the 1911 TT there could be seen examples of epicyclic hubs, epicyclic engine-shaft gears, sliding countershaft gears and expanding pulley gears. Such ability to vary the gearing, if only modestly by later standards, helped overcome the previous situation where the single gear fitted had to be a compromise between being high enough to offer the best possible speed on level going, without robbing the machine of reasonable hill-climbing ability.

Riders knew there was another transmission problem to cope with when tackling gradients, for the belt drives fitted to most early machines to convey engine power to the back wheel tended to stretch in use, thus allowing the belt to slip under load. Some makes used a jockey-wheel to help maintain tension, but problems of belt grip/slip could be aggravated by wet conditions, or by the belt getting coated in oil from the usually less than oil-tight engines of the day. It was not unknown for a belt to break in use and most competitors carried a spare (pre-stretched) belt during a race, plus the means to repair a broken one.

P. Owen is ready to race his belt-driven Forward in the Junior race of 1912. The Forward Company’s venture into motorcycle manufacture was short lived, for it found it more profitable to specialize in the making of drive belts and their associated fasteners.

With a lap of the new Mountain Course for 1911 extending to more than 37 miles, riders were keen to get in as much practice as possible and a pre-race report of the time said: ‘Once again between the hours of three and seven in the morning, when most people are wasting these good hours in bed, scenes of excitement will take place, and the roars of the engines will be heard.’ Those were clearly the words of a motorcyclist and it is doubtful if people living adjacent to the course spoke of the early morning practice sessions with such enthusiasm. Before practice riders were told: ‘All dangerous parts of the course will be marked by banners some distance from the point of danger’.

Machine reliability was a necessity for those seeking TT success and New Hudson was said ‘to have everything brazed on and every nut is split-pinned’. Despite the striving for reliability, most companies experimented with some new aspect of design during practice. In attempts to lighten and improve lubrication of pistons, Norton fitted one with thirteen circular grooves (excluding ring grooves) in their single-cylinder models, while Zenith lightened their pistons with holes in the walls. Brown and Barlow appeared with a new variable-jet carburettor that was chosen for use by several riders, and former winners Harry and Charlie Collier were back seeking further glory on Matchless machines fitted with a variable pulley gear offering belt-driven ratios between 3:1 and 5:1.

A problem with some variable pulley systems with a normal fixed-length drive belt was that as the size of the pulley was changed to alter the gearing, the belt could lose tension and slip. Various methods were used to deal with this problem. Zenith overcame it with their ‘Gradua’ arrangement, which moved the rear wheel to shorten or increase wheelbase as pulley diameter changed. The Rudge concern was uncertain what form of gearing to use in 1911 and a pre-race report said, ‘The Rudge TT models will be of the ordinary standard pattern as far as outward appearance goes, but it is not yet decided whether a direct drive, clutch or two-speed gear will be used. Probably one of each type will ultimately be adopted.’ In the final run-up to the TT, Rudge designed an improved form of variable pulley system that allowed constant belt tension to be maintained: although it allowed only a variation in gearing of 5¾ to 3¼ to 1, they named it the ‘Multi’.

Several Rudge-Multis being prepared on the Island for the TT.

The American Indian Company was another manufacturer with variable gearing, and its system was advanced for the time, comprising a two-speed countershaft gearbox, clutch, and all-chain drive. It was a system that greatly reduced the problems associated with the climbing of hills and one that paid rich dividends in the Isle of Man in 1911, for their twin-cylinder machines (with engines scaled down to the 585cc TT limit and featuring overhead inlet and side exhaust valves) came home a triumphant 1-2-3 in the Senior TT. Englishman Oliver Godfrey was the man to get his name inscribed upon the Tourist Trophy by taking first place from his team-mates Charles Franklin and Arthur Moorhouse, and their red Indians finished ahead of machines from Ariel, Bradbury, Zenith-Gradua, NSU, Rex and others.

A copy of the original Tourist Trophy was made to award to the winner of the newly created Junior race, and Percy Evans was the first recipient after riding his V-twin (Humber) into first place, nine minutes ahead of Harry Collier (Matchless).

The start and finish point of the 1911 races in Douglas was located on a flat section of road between the bottom of Bray Hill and the descent to Quarter Bridge, where the latter’s downward slope was very welcome to those who had difficulty bump-starting their machines. Clerk of the Course Mr J.R. Nisbet controlled affairs at the start with the aid of a megaphone, scoreboards were erected at the side of the road, the timekeepers had a small wooden shed to work in, and the press occupied a room in an unfinished cottage close to the finishing line. However, there was no room for a riders’ ‘replenishment area’, so official refuelling points were created at Braddan and Ramsey.

Charles Franklin sits astride his Indian before the start of the 1911 TT, in which he finished in second place. Note the spare butt-ended inner tubes tied around his waist in case he needed to repair a puncture.

Although it is not possible to make a direct comparison between the old and new TT courses, it is worth mentioning that Oliver Godfrey’s average race speed over the Mountain Course in 1911 was 47.63mph (76.65km/h), while Charlie Collier’s winning speed on the easier St John’s Course in 1910 had been 50.63mph (81.48km/h).

Outside Assistance

In what had become the customary post-race squabble over non-compliance with race regulations, Charlie Collier (Matchless), who was initially awarded second place in the 1911 Senior race, was disqualified for taking on petrol at other than the officially permitted refuelling points, and Jake De Rosier (Indian) received the same treatment for borrowing tools to adjust his valve-gear out on the course. Their actions came under the heading of receiving ‘outside assistance’, an expression that has become enshrined in TT lore as a forbidden activity. A rider was only permitted to carry out repairs on the course using the tools that he carried with him, but in the quest for lightness and speed some riders carried fewer tools than they had previously been obliged to do by the race regulations. TT history shows that the receipt of ‘outside assistance’ has resulted in the disqualification of many other riders down the years, several of whom lost race wins as a result.

Commercial Pressures

Even from the earliest days there was a strong commercial aspect to the TT races. While manufacturers entered knowing that racing yielded useful practical lessons in design and construction, they soon became aware that mere participation in a TT race raised the status of their products and increased their appeal to many potential buyers in what was a crowded but, by 1911, a profitable market. The esteem earned by TT participation was also sought by associated suppliers such as petrol and tyre companies (known as ‘The Trade’), and they were prepared to pay to have their names linked to TT success. The recipients of such payments were usually the successful riders and a report in Motor Cycle in 1911 opined that ‘it is worth nearly £200 to a trade rider to win the Tourist Trophy. Apart from the £40 cash offered by the ACU, a windfall from the makers of the tyres, belt, magneto, carburettor, petrol and the oil employed by the winning machine usually follows’. With such rewards available, it is little wonder that riders sometimes attempted to bend the rules by accepting ‘outside assistance’ to get to the finish.

The 1911 TT performance of Indian and other machines fitted with variable gears provided a convincing demonstration of the way forward for the motorcycle industry, and entries for the 1912 Senior TT featured only one single-geared machine. In yet another change of rule regarding engine sizes, the upper engine capacity limit for the Senior class was set at 500cc for all entries, singles or multis, and a similar ruling applied in the Junior, where the upper limit was set at 350cc. But all was not well on the organizing side, for there were differences of opinion between the ACU and British manufacturers over the running of the TT. Some of the latter boycotted the 1912 event at the end of June, and entries fell to twenty-five Juniors and forty-nine Seniors.

In an overview of the motorcycling scene in 1912, the British press considered that ‘The industry has settled down into a comfortable state of energetic prosperity’. On the run-up to the TT, however, it stressed the importance to the British motorcycle industry of recovering the Tourist Trophy from the foreign victor of the previous year.

Not everyone took Indian’s fine win in the 1911 TT in true sporting spirit, as this advertisement from Norton shows. Despite the disparaging tone that Norton adopted towards the American product, neither of its single-cylinder entries actually finished the race. It was the first year that Norton used a new 79 × 100mm bore and stroke for its engine, but one with those ‘longstroke’ dimensions then remained a feature of the Norton range until 1963.

Approaching May Hill on the outskirts of Ramsey in 1912, this rider takes a wide line to maintain momentum. Standing water can be seen in the road and riders sometimes used the left-hand footpath to avoid the worst conditions here.

A Two-Stroke Win

The Scott marque’s TT debut in 1909 had not met with particular success, but in the 1911 Senior race Frank Phillipp gave a hint of things to come by setting the fastest lap at 50.11mph (80.64km/h). He also anticipated future fashion by riding in leathers that were dyed Scott purple. Unconventional in many respects, the Scotts entered for the 1912 TT were powered by 486cc twin-cylinder, two-stroke engines fitted with water-cooled barrels, gear-driven rotary valve, and with the engine cradled in an open frame that had an early form of telescopic front suspension. With two-speed gearboxes and all-chain drive, they were light, nimble, fast and, as the race showed, sturdy enough to last for five laps of racing over the Mountain Course and bring Frank Applebee home to victory six minutes ahead of the opposition. Applebee’s race average speed was 48.69mph (78.36km/h) and it would have been a Scott 1-2 had the rear tyre of his team-mate Frank Phillipp not burst on the last lap when he was holding a secure second place.

This photograph is from 1913 when a Scott ridden by Tim Wood was again victorious in the Senior TT. Using an early form of ‘dump-can’, the rider adds fuel whilst his attendant tops up the radiator.

Scott motorcycles were initially built in Bradford and were technically ahead of the opposition almost from Alfred Angus Scott’s first experiments with a powered two-wheeler in 1901. An exponent of two-strokes from the outset, such was his sweeping success when he entered them in major competition that other manufacturers persuaded the ACU to handicap his product, and for several years an ‘equalizing factor’ was applied whereby his two-stroke engine’s actual capacity had to be multiplied by 1.32 for competition purposes. Scott used this point to advantage by stressing it in the company’s catalogue (even after the ruling was rescinded). It was respected racer, journalist and author Vic Willoughby who later wrote:

Scott had an uncanny flair for combining highly original ideas with sound, practical engineering. Such was the range of his vision that not only were the basic features of his design practically unchanged throughout the marque’s production, but he anticipated technical trends by up to half a century.

Another slightly unconventional machine took victory in the Junior race of 1912. This was the Bristol-built Douglas fitted with a horizontally opposed, twin-cylinder side-valve engine mounted longitudinally in the frame, thus giving it an overall low build. The 1912 Junior event was the first TT to be held in wet conditions and they proved a severe challenge to the smaller machines. Bill Bashall’s winning Douglas was belt-driven and he is said to have stopped eight times to adjust the belt that slipped badly in the wet and muddy conditions. Only eleven riders finished the race because, apart from belt troubles, many were forced out with electrical problems due to ineffective shielding of magnetos and sparking plugs. Among the lessons learnt from this wet event were that the business of weight-saving for racing by reducing the shielding to belts and electrics could be taken too far. Bashall’s average speed of 39.65mph (63.81km/h) in 1912 is the lowest ever race-winning speed recorded over the Mountain Course by a ‘Junior’ machine.

The roads faced by TT competitors were still surfaced with rolled macadam. They were narrow, bumpy, with a loose, stony and often pot-holed surface containing many horseshoe nails, while most of the stretch over the Mountain comprised just two stone-filled wheel ruts with a grassy rut down the middle. Not only did riders have to be exceptionally brave to race over them at speed, but the physical challenge of racing for five laps and 187½ miles over those primitive roads was such that competitor ‘Pa’ Applebee (father of 1912 Senior winner, Frank) was quoted as saying: ‘a rider was considered amazingly fresh if he could stand at the end of a race’.

Quarter Bridge during the very wet 1912 Junior TT, showing the conditions riders had to cope with for the 150-mile race distance.

To further emphasize the basic conditions under which the races were run, marshals were few and far between, particularly during early-morning practice. There were just three official telephone points on the Course: at the grandstand, Ballacraine and Creg ny Baa, and medical support was very scarce. If a rider fell and needed medical assistance he might receive it from one of the few policemen or volunteer ambulancemen on duty, but if it was a serious injury a message would have to be taken to the nearest doctor (a major task, for there were no radio communications or mobile phones) and the doctor would have to make his way to the scene of the accident. Depending upon where the rider was located it might then be possible to get him off the Course and to hospital by back roads, or he might have to remain where he fell until the race finished. A race win in those days took nearly four hours and by the time all the stragglers were in it could well be over five hours from the starting time.

A TT victory became much coveted by manufacturers and the supporting trade concerns, for it virtually guaranteed a boost to their profits. Victorious riders would also benefit, for apart from the prize and bonus money to be earned, their names would be publicized and become familiar to motorcyclists of the time. Taking advantage of the associated glory that ensued, it became common practice for them to go into business and profit from their names: the winners of the 1911 and 1912 TTs, Oliver Godfrey and Frank Applebee did just that, and in later years they were followed by many others, thus establishing the ‘Rider Agent’ category of dealer that many were proud to advertise.

Two-Day TT

Pursuing its theme of increasing the TT’s challenge to riders and machines, in 1913 the ACU extended the race distances to seven laps for the Senior and six laps for the Junior and, with full manufacturer support restored, received a combined total of 148 entries. However, mindful of the demands that the course made upon riders, a report of the time noted that:

It was supposed that even the toughest athlete, in the pink of condition, could never stand six or seven successive TT laps on the same day, so two laps of the Junior were run off on the Wednesday morning, after which the machines were locked up and the Senior men did three laps. Everybody recuperated during Thursday, and on Friday the survivors in both races covered four laps together.

So, after their day’s rest, Senior and Junior riders were set off alternately, and to further differentiate between the classes they wore coloured waistcoats: red for Seniors and blue for Juniors. Although the two-day TT was an interesting experiment, it was not repeated.

In the Junior race, where thirty-two of the forty-four entries were mounted on twins, Hugh Mason left his hospital bed to ride a NUT-JAP V-twin to a brave win, having crashed in practice earlier in the week. In the Senior, where only twenty-four of the 104 entries were on twins, victory went to a Scott for the second year running. It produced the closest finish since the races began, with Tim Wood (Scott) snatching victory from the relatively unknown Ray Abbott (Rudge) who, when leading on the last lap, overshot a corner and lost the race by a mere five seconds.

A busy start-line scene in 1913 when riders were despatched from a point on the flat between the bottom of Bray Hill and Quarter Bridge.

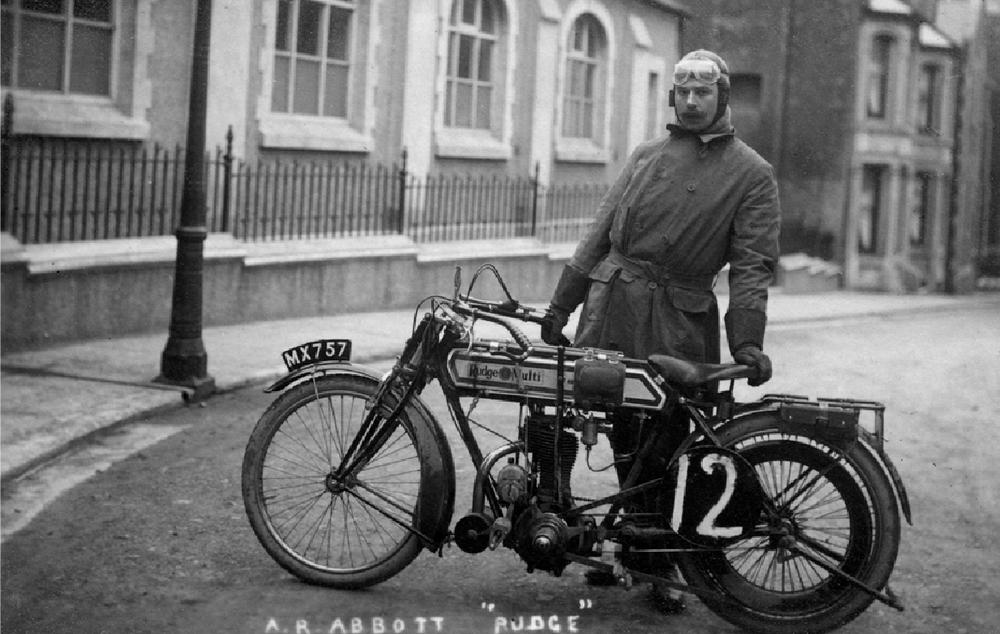

The man who came second in the 1913 Senior TT, Ray Abbott, poses with his Rudge Multi.

The winning Rover team of 1913.

Prize money was increased to £50 to the winner of the Senior race in 1913 and £40 to the Junior winner. To encourage support from the motorcycle trade, a Manufacturers’ Team Award was presented for the first time and, with its members Brown, Lindsay and Newsome being the only team to finish intact, the award went to the Rover concern.

Spreading the Word

At the time of the first TT in 1907 there were 35,000 motorcycles registered for use on the roads of Britain and by 1914 there were 124,000. Although many were bought and used for utility purposes, the majority were acquired by ‘enthusiasts’ who were prepared to put up with the anti-motoring attitude of the police and public, the relative unreliability of machines, poor roads, restrictive speed limits, and so on, all so that they could pursue their passion for travel by powered two-wheelers. Most of them bought the two principal specialist magazines of the time, Motor Cycle and Motor Cycling, to keep up with affairs, and this gave the magazines enormous influence over the thinking of their readers. Fortunately the magazines were very pro-TT, printing much news before and after the races, and raising the profile of the event and of the successful machines and riders. As early as 1911 Motor Cycle described the Isle of Man as ‘The motorcyclist’s Mecca’, although relatively few riders were able to make the TT pilgrimage before the First World War. Recognizing this, Motor Cycle sought to satisfy the tremendous demand for race information from those who could not attend by telegraphing progress reports and results to motorcycle dealers across Britain. The dealers would then post them in their showroom windows for information-hungry enthusiasts to read. Not to be outdone in catering for its TT-minded readership, Motor Cycling arranged day trips to watch the Senior race, involving travel by train to Liverpool and then by Steam Packet boat to Douglas. It tempted its readers with the words ‘Men who have watched every kind of sporting event have often said that nothing in the world is so thrilling to watch as this hotly-contested struggle for the blue ribbon of the motorcycling world’.

The many news reports, the advertising and the increasing numbers of visitors saw the names and places on the Isle of Man TT Mountain Course become part of the language of the average motorcyclist, just as they are today. Places like Bray Hill, Ballacraine, Ballaugh Bridge, Parliament Square in Ramsey, and spots on the Mountain like the Bungalow and Creg ny Baa were spoken about with authority by many who, although they may never have visited the Island, carried mental pictures of the locations, the lines that riders should take and the danger involved, with the majority of that information having come from the detailed reports carried in the motorcycle press.

Maps of the 37¾-mile Mountain Course show many of the names that it has acquired over the past hundred years. When first used the Course was slightly shorter, because riders turned right at Cronk ny Mona on the outskirts of Douglas and headed across to the top of Bray Hill.

By 1912 the TT’s high profile saw manufacturers trying to increase the number of machines they sold by developing more sporting versions of their touring motorcycles. Indeed, many included a ‘TT Model’ in their catalogues (whether they contested the event or not) and this became a generally accepted name for any machine without pedals, but fitted with flat or slightly downturned handlebars, tuned engine and sporting pretensions.

The TT’s growing popularity with motorcyclists was generally shared by the Manx people, although there were dissenting voices from a small but vocal element of locals who spoke of the motorcycles and races ‘desecrating the peace of Mona with these dangerous nuisances’. A newspaper report from the early days, however, confirms the high level of local support that existed, claiming that ‘The Island indulged itself in a National Holiday’ on race days. So frequent did this indulgence become that the authorities eventually declared the day of the Senior TT race to be a Bank Holiday – as it is on the Island today.

A New Start

It was in 1914 that the start of the race was moved to the top of Bray Hill, just south of St Ninian’s crossroads. This allowed the creation of a grandstand for 1,000 people and pits for riders to refuel, although the latter were very cramped. The organizers still referred to the pits as the Replenishment Depot. While it was a place where a rider could have the services of one assistant, he was limited to helping with topping up petrol, oil and water, as only the rider was allowed to do any work or repairs to his machine. Basic information on the progress of a race was still conveyed to those at the start area by the marking of information on large scoreboards; this was augmented by a man with a megaphone, for public address systems and radio commentaries were still to be invented.

A machine going through the weighing-in process prior to the 1914 TT.

Both the Junior and Senior TT races had entries from approximately twenty different makes of machine. They were examined for compliance with the regulations on the day before each race and usually left overnight in a tent under the control of the ACU and a policeman. However, at about 9pm on the evening prior to the Junior race a squad of soldiers with fixed bayonets surrounded the tent and remained on guard all night, for there had been rumours in the Island about a possible disturbance by suffragettes.

Safety

Organizers, riders and spectators had been aware from the very first TT that the racing of motorcycles was a dangerous business – indeed, that was the attraction for many. It was in 1911 that Victor Surridge earned the sad distinction of becoming the first TT fatality when he crashed his Rudge at Glen Helen during practice.

Concerned to ensure a reasonable level of competence among those who entered the races, from 1914 race regulations stipulated that riders were required to complete a minimum of six laps of practice in order to qualify to race, an additional rule being that one of those laps had to be completed within a maximum time of seventy minutes for Junior and sixty minutes for Senior runners. Not all of that year’s total entry of 160 reached the qualifying standard and thus some were not permitted to start.

To further improve safety, the organizers introduced an ambulance sidecar outfit at Ballacraine in 1913. For 1914 they increased the number of marshals and rigged more warning banners on the approach to danger points. Their early-morning arrangements for opening the gates across the Mountain Road prior to practice, however, were not totally effective, and early in the 1914 meeting there were alarming reports in relation to the gates, admitting that ‘already several smashes have occurred’.

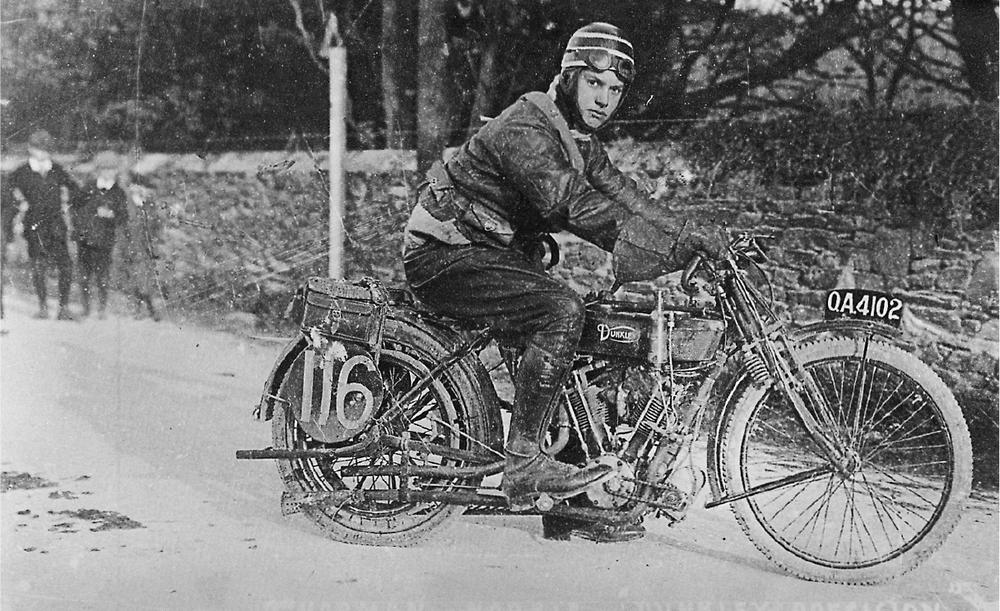

Norman Norris (Dunkeley Precision), dressed to race in 1914. Note the obligatory cut-outs around the ears so that the rider could hear those overtaking.

When the races switched to the Mountain Course in 1911 much was made of the demands that would be imposed on machinery by the arduous climb from Ramsey to Snaefell, but riders soon found that – even discounting the common hazard of wandering sheep – there were considerable dangers to both man and machine from the flat-out descent towards Douglas and the finish. F. Bateman was contesting the lead of the 1913 Senior when a tyre came off the rim and burst while he was riding down the Mountain at speed. Bateman was killed and there were several other serious accidents in 1913, some of which were attributed to racers with mainly ‘track’ experience trying too hard on the TT’s ‘road’ course. The history of the organization of the TT shows that lessons are usually learnt from the mistakes, incidents and accidents that occur, and that measures are subsequently introduced to counter the problems revealed. In a safety-oriented move for 1914, security bolts were made compulsory to help keep the beaded-edge tyres on their rims. Then, although riding gear had progressed to the stage where most riders wore leather jackets, trousers, boots and gloves, there was no recognized form of headgear that offered protection to such a vital area. Tom Loughborough, who was Secretary of the ACU, ‘Ebby’ Ebblewhite, the TT Timekeeper, and Dr Gardner, the Medical Officer at Brooklands, got together and produced an ACU-approved design of crash-helmet that was made compulsory wear for TT competitors in 1914.

The Certificate of Performance issued by the ACU to John Marston Ltd, maker of Sunbeam motorcycles, in 1914. Notice that Tommy de la Hay, in thirteenth place, was racing for almost 5 hours.

Although rider safety was at the forefront of the organizers’ minds in 1914, they could do little to prevent the fatal crash of third-placed Freddie Walker at the finish of the Junior race when, dazed after earlier falls, he failed to turn right at the top of Bray Hill and crashed into a barrier that had been placed across the road to define and safeguard the course.

Victory went to single-cylinder machines in both Junior and Senior races in 1914, thus reversing the trend of the previous few years that had seen twins to the fore. Speeds had increased relatively slowly despite four years of intense competition over the Mountain Course between top makes such as Indian, Matchless, Triumph, Rudge and Scott, but the number of finishers had gradually grown as manufacturers achieved greater reliability in the stern test of racing for six laps and some 225 miles. Winner of the Junior race of 1914 was Eric Williams on an AJS that the factory had put much effort into preparing for the TT. Despite experiencing many troubles during practice, AJS riders also took second, fourth and fifth places in the race. The result boosted sales overnight and brought about the need for the four Stevens brothers (who comprised AJS) to take larger premises in Wolverhampton. The Senior race saw a spirited battle for race honours, with a new rider and new make of machine challenging for the lead in the form of Howard Davies (Sunbeam), but victory eventually went to Cyril Pullin who averaged 49.49mph (79.64km/h) on a belt-driven Rudge. Howard Davies had to share second place with Oliver Godfrey (Indian) – an unusual occurrence – for both finished thirty-six seconds behind the winning Rudge. It proved to be the last TT victory by a belt-driven machine and, with the onset of the First World War just two months away, the last TT race for six years.