Joe Craig had been a successful racer and employee of Norton in the latter half of the 1920s, but he left them in 1928 when the Walter Moore-designed ohc racing engine went backwards in performance. Returning after Moore left for NSU in 1929, Craig took charge of the practical side of design and set about producing a new race engine with Arthur Carroll providing the engineering theory. Results achieved with the new engine in 1930 showed they were on the right track and by the time of the 1931 TT the Junior and Senior Norton race machines had, as well as the new engines, four-speed gearboxes with fully enclosed positive-stop gear change mechanism, forks and brakes of Norton manufacture (previous items were bought in) and other minor changes.

Whatever advances Norton had made, Rudge, the double TT winners, had not been idle and its several victories early in the 1931 season indicated that it was still the team to beat. But Craig knew that his Nortons were now very competitive, and to enhance Norton Motors’ chances of success some of the best riders were engaged, arriving at the 1931 TT with a team comprising Jimmy Guthrie, Stanley Woods, Tim Hunt and Jimmy Simpson. Managed by Craig, the machines and men representing the Bracebridge Street factory were formidable opponents for the twenty other makes and 150 other riders entered for the meeting. Eight of those other makes were foreign, including NSU, Moto Guzzi and Husqvarna.

Factory teams and trade representatives usually tried to get settled into their garages and hotels a day or two before practice opened, which in 1931 was on Thursday 4 June. Former rider Reuben Harveyson represented Perry Chains and Lycett saddles, and advertised that he would be based at the Castle Mona Hotel. Mr Hill of Tecalemit (grease) was reported to have been busy with grease nipples and guns in many of the team garages, while Castrol reminded people of earlier TT successes by advertising in advance of the races that the Senior had been won fifteen times in succession on their oils.

Mixed Weather

In what some might say was a typical week of Manx weather, competitors had to cope with heavy mist, rain and strong winds in some practice sessions, while others were dry and sunny. Such sessions were still restricted to early mornings and that of Saturday 6 June was reported as ‘The Worst Morning Ever’ for weather. Despite the deplorable wet and foggy conditions, sixteen riders braved the elements, with several of them putting in two laps. In contrast, Monday morning offered almost perfect conditions and Jack Williams (Raleigh) was clocked at an average speed of 101.2mph (162.86km/h) over a measured mile at Sulby, while Tim Hunt (Norton) averaged 100.6mph (161.85km/h) at the same location.

The Norton team showed well in practice, with Tim Hunt setting the fastest lap in the Senior class on two occasions, while Jimmy Simpson and Stanley Woods vied for the fastest Junior lap, and Stanley bettered the lap record during the week. Encouraging as those practice performances were, after the permitted nine sessions Ernie Nott (Rudge) and Freddie Hicks (AJS) were also seen to be very fast in the Senior class and, although of no great concern to Nortons, Nott and Graham Walker were the fastest Lightweights on their 250cc Rudge machines. But performances in practice are difficult to evaluate, for riders and teams sometimes seek to conceal their true capabilities from the opposition. Norton’s racing effort received the full support of its senior management, and Director Dennis Mansell, who was with the team on the island, later told how he secretly timed Norton riders and the opposition over the stretch from Kate’s Cottage to Hillberry. Discovering that the Nortons were consistently fastest over this stretch was valuable information that the team was able to use in its race strategy. But although the Norton and Rudge factories were clear favourites to carry off the race wins in 1931, at the conclusion of practice press pundits found it difficult to forecast which individual rider would come home first in each of the three races (Lightweight, Junior, Senior).

Tim Hunt (Norton) was both fast and successful at the 1931 TT.

The early 1930s saw much spectator interest in the TT with record crowds and vehicles coming to the island. One unusual item of concern was that with the growth in use of light aircraft, their pilots might try to fly the course at low altitude to view and obtain photographs of the action. Just prior to race week the Air Ministry issued a notice to fliers requesting them not to overfly the course at less than 2,000ft.

The 1931 Races

The Monday of race week was blessed with good weather for what was expected to be a hotly contested Junior race. Jimmy Simpson (Norton) held the lead for the first four laps. After a slow start due to plug trouble, Tim Hunt (Norton) worked his way through the field to lie second. Hunt then took the lead on lap five and went on to win from Jimmie Guthrie (Norton), with Ernie Nott (Rudge) third. To Hunt went race and lap records, his best lap of 75.27mph (121.13km/h) being an impressive 3mph faster than the record set in 1930 by the then all-conquering Junior Rudges.

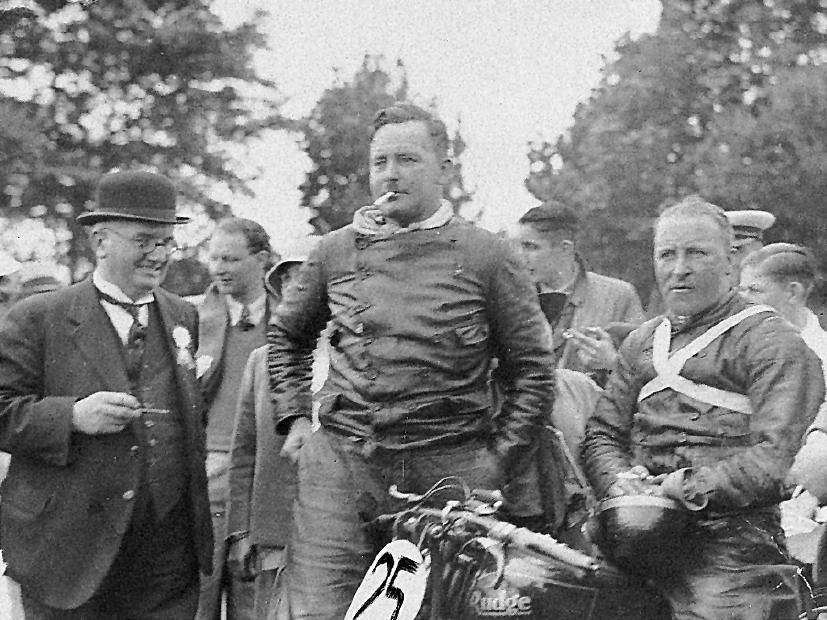

Rudge riders Graham Walker and Ernie Nott (seated) at the end of the 1931 Lightweight race.

Rudge did achieve a popular victory in Wednesday’s Lightweight race when ‘heavyweight’ Graham Walker came home at the head of the field on his 250, after the leader for most of the race, Ernie Nott, experienced tappet troubles with his Rudge, which dropped him to fourth. Graham’s first TT had been in 1920 and now, aged thirty-four, his win was watched from the Grandstand by his wife and young son Murray.

The successful Norton team after their 1-2-3 victory in the 1931 Senior TT: winner Tim Hunt (30), second Jimmie Guthrie (20) and third Stanley Woods (16). Norton team-manager Joe Craig stands between Hunt and Woods.

This photograph of Stanley Woods gives a side view of Norton’s successful racer.

The Senior TT had been known as the ‘Blue Riband’ event for many years and it gave Norton the chance to make an emphatic statement of its superiority over other manufacturers by taking the first three places at record speeds with Tim Hunt, Jimmie Guthrie and Stanley Woods. The Nortons led home the Rudges of Nott and Walker. After becoming the first man to lap at over 80mph, Simpson was forced to retire the fourth ‘works’ Norton after a fall at Ballaugh Bridge due to a grabbing front brake. It was a race that earned the headline ‘England Defeats All-Comers’, for, apart from Ted Mellors (NSU) in sixth place, the remainder of the foreign challenge faded during the race. Indeed, by the end of the week it was clear that TT supremacy lay with British men and machines in all classes. Ordinary motorcyclists who were inspired to emulate the members of the winning Norton race team could, for 1932, buy road-going replicas of the race machines, which the factory called the Model 30 International (490cc) and the Model 40 International (348cc), while the cheaper CJ and CS camshaft sports models remained available.

Reduced Entries

Although no-one could come up with a valid reason why, entries for the 1932 meeting were down by slightly over one-third (to ninety-five) on the 1931 figures. The quality was still there with ‘works’ entries, trade support and top riders; although there was reduced foreign interest, Jawa brought four-stroke machines to contest the Senior under the guidance of celebrated Brooklands star George Patchett.

It was inevitable that the reduction in entries had pessimists questioning the future of the TT, but a long article in Motor Cycle and Cycle Trader offered a careful analysis of the many factors that combined to make up the TT meeting. It recognized that the nature of the races could change significantly if manufacturers and the trade withdrew support, but it did not think they would, and so concluded with the encouraging words: ‘We think, therefore, that those who feel anxious for the future of the races can safely rid themselves of their apprehensions’.

While the Island prepared itself with enthusiasm for a royal visit from Prince George, who would watch the Senior race, riders got on with the business of practising and bringing their machines to race pitch. They could have done without what a local newspaper described as ‘the biggest adventure’ of the second morning’s practice, which involved ‘the appearance on the Course of 5 or 6 horses’. The beasts had been found loose between Union Mills and Glen Vine before the first rider came through and were herded into a field beside the course. Freeing themselves after practice started, they regained the course and went clattering through Crosby, increasing speed with every rider that passed them. Making it to the top of the hill before The Highlander, they were eventually rounded up by two young spectators.

Stanley’s Double

Although pushed hard in the Junior race by the Rudges of Ernie Nott and Henry Tyrell-Smith, it was the Norton-mounted Irish rider Stanley Woods who came home first in that opening race of the 1932 TT meeting, adding 3mph to the average race speed and the same amount to the lap record. Stanley led from start to finish, and while his three Norton team-mates all occupied top-three placings at some stage of the race, it was left to the Dubliner to keep the Rudges at bay. After its sweeping successes of 1930 the Rudge concern was finding it difficult to record another win and, although there were no Nortons in the Lightweight event to worry about, they even had to accept second and third positions in the mid-week race for 250s, where Leo Davenport set record speeds to win on his New Imperial ahead of Graham Walker and Wal Handley.

An unusual view of Ballaugh Bridge in 1932, as it is tackled by Ernie Knott (Rudge).

The four-man Norton team started as clear favourites for the Senior event and did not disappoint its followers. On machinery that was lighter than the previous year, but otherwise subject to only minor improvements, the team matched its 1931 performance by taking the first three places to record another hat trick with Stanley Woods, Jimmy Guthrie and Jimmy Simpson finishing 1-2-3, at record-breaking speeds. The only disappointment for Norton was that the previous year’s winner, Tim Hunt, was forced to retire after falling at Quarter Bridge on the first lap. When the race got under way at 10am on the Friday morning, Jimmy Simpson held the lead for the first two laps and no doubt had thoughts of a possible win. Despite setting the fastest lap of the race at 81.50mph (131.16km/h), however, Jimmy was overtaken first by Woods and then by Guthrie after his front brake cable snapped. In his ten-year TT racing career to that point, Simpson had started in more than twenty races, leading many of them, set new speeds (first man to lap at 60, 70 and 80mph), taken lap records, but suffered many breakdowns. It really seemed as though he was destined not to win on the Island.

Why so Named?

Handley’s Corner

Previously a spot with no particular name, the tricky left-right bend soon after the 11th Milestone, now known as Handley’s, earned its name when Wal Handley crashed there during the Senior race of 1932. Geoff Davison tells in The Story of the TT how in the crash Handley ‘damaged his spine and lay for some seconds in the road, unable to move and at the mercy of any approaching machine; and furthermore his Rudge was alongside of him, with the engine roaring away and petrol flowing all over the place, so that Walter himself was soaked in it’. Disaster was avoided when help quickly arrived. When Davison visited Wal in hospital a few hours later ‘he was as cheerful as ever and in his own inimitable style was describing it as a humorous incident’!

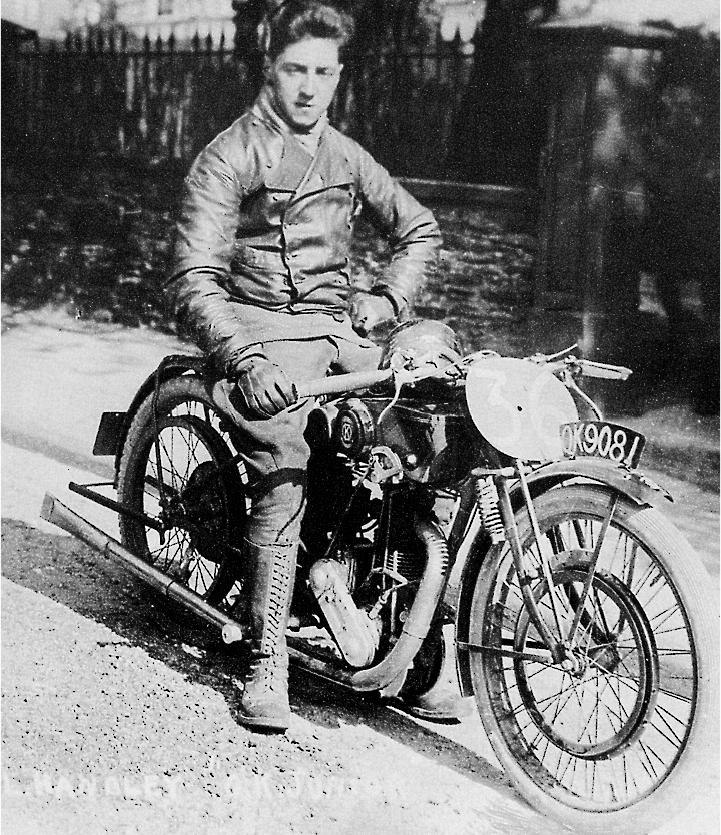

Wal Handley made his TT debut in the 1922 Lightweight race on a 250cc O.K. Between 1922 and 1934 he rode in twenty-eight TT races, taking four victories.

Almost Another Sidecar Race

The organizers included a race for sidecars in the 1933 TT programme, but although the press were supportive – for there was talk of some of the top solo riders adding a third wheel and competing – a report of the time said: ‘The Trade were against the Sidecar race and set their faces against it’. With only eight entries from three-wheeled competitors, the proposed race was scrapped and the report concluded: ‘It is unlikely that this once popular feature of TT week will ever be revived’.

The decision was not well received by those who had prepared outfits to race. One of them was Tommy Hatch, who agreed to ride a Scott Special outfit built by large Liverpool dealers A.E. Reynolds. Hatch reported that he had ‘selected a champion gymnast as my passenger’. Another contender was Alan Bruce, who had a JAP-engined Vincent HRD fitted with a banking sidecar ready to go. Thwarted by the decision to cancel, Bruce told ‘Kirkstone’, the motor cycling correspondent of the British daily News Chronicle, that he would claim the right to attempt to break the sidecar speed record over the course before one of the races. The record stood at 57mph (91.7km/h) and Bruce confidently expected to average 67mph (107.8km/h). Unfortunately, the organizers did not consider that Bruce had any right to make a record-breaking attempt, so the record remained intact.

Questions?

The TT races attracted attention and comment from all over the world, and the well-informed Manx press also had views on the races that ran on its doorstep. The Isle of Man Weekly Times made a couple of pertinent points in its pages on the run-up to the 1933 TT. Foreign entries totalled twenty-three and most TT fans felt that the presence of men and machines from abroad added interest to the races. However, the paper asked if the Island was getting value-for-money from the monies it paid towards the expenses of foreigners, saying that ‘none of them had the remotest chance of winning’. Having questioned the worth of the foreign entry, it then pointed an accusing finger at the successful Norton team with: ‘While we admire the Nortons, we doubt if their repeated successes are in the best interest of the races’. Such provocative comments hardly seemed likely to benefit the island or the TT but, right or wrong, the Manx press has never been afraid to speak its mind on the topic of the races, for it is a subject that, in one form or another, affects every resident.

A Double Treble

The question of whether domination of the major TT classes by Norton served to discourage other manufacturers from entering was aired in other publications, but with the entry for 1933 matching that of 1932 there did not seem to be too strong a case. It was certainly not a topic that the Bracebridge Street manufacturer troubled itself with, as it proved by taking the first three places in both the Junior and Senior events. It was Stanley Woods, at the peak of his form, who came home first in both races, setting new race and lap records in the process. While there were other Nortons competing, it was the ‘works’ riders who accompanied Stanley onto the rostrum, with Tim Hunt and Jimmie Guthrie taking second and third in the Junior. In the Senior, Jimmy Simpson was second, Tim Hunt third and Jimmy Guthrie fourth, putting all four ‘works’ Nortons firmly at the head of the field. Since before the time that the TT moved to the Mountain Course Norton’s advertising had described its motorcycles as ‘Unapproachable’; in 1933 no one could deny the truth of the slogan, for its dominance also extended to Continental Grand Prix, where, often riding to orders as to who should come home first, its four-man team won most of the events.

Rudge was unable to commit the finance or technical input to its racing effort of previous years and there was no Rudge in the top ten in the Junior of 1933, while Ernie Nott’s fifth place was their best result in the Senior. Although not a serious challenge to the ‘works’ Nortons at that stage, Velocette machines put in some excellent performances, giving a hint of what was to come from the Hall Green manufacturer in future years.

Although TT success had eluded them for a few years, Velocette was proud to include this transfer on the tanks of its road-going machines in the 1930s.

The Lightweight race offered a far more open contest with Excelsiors, New Imperials, Cottons and Rudges all considered capable of winning. On the almost straight from the drawing board Excelsior ‘Mechanical Marvel’ models, Wal Handley and Sid Gleave set the pace during the race, and at the finish it was Gleave in first place, followed by Charlie Dodson (New Imperial) and Charlie Manders (Rudge). The winner’s average speed was slightly up on 1932 at 71.59mph (115.21km/h) but the lap record was not broken.

At Last!

Having raced every year since 1922 in Senior, Junior and one Sidecar race, the speedy Jimmy Simpson finally achieved his sought-after TT win in 1934. It was gained under slightly unusual circumstances, for not only did his win come in the Lightweight class – at the first time of racing a 250 on the Island – but he did not rush off flat-out from the start in his customary manner. Indeed, mounted on a Rudge, it was the third lap before he moved into first place, a position he held to come home more than three minutes ahead of similarly mounted 250 runners Ernie Nott and Graham Walker in wet and misty conditions, recording one of the most popular of TT victories. In a fitting tribute to a man who set the fastest lap in eight TT races, today’s award to the overall fastest solo rider at the TT is named the Jimmy Simpson Trophy.

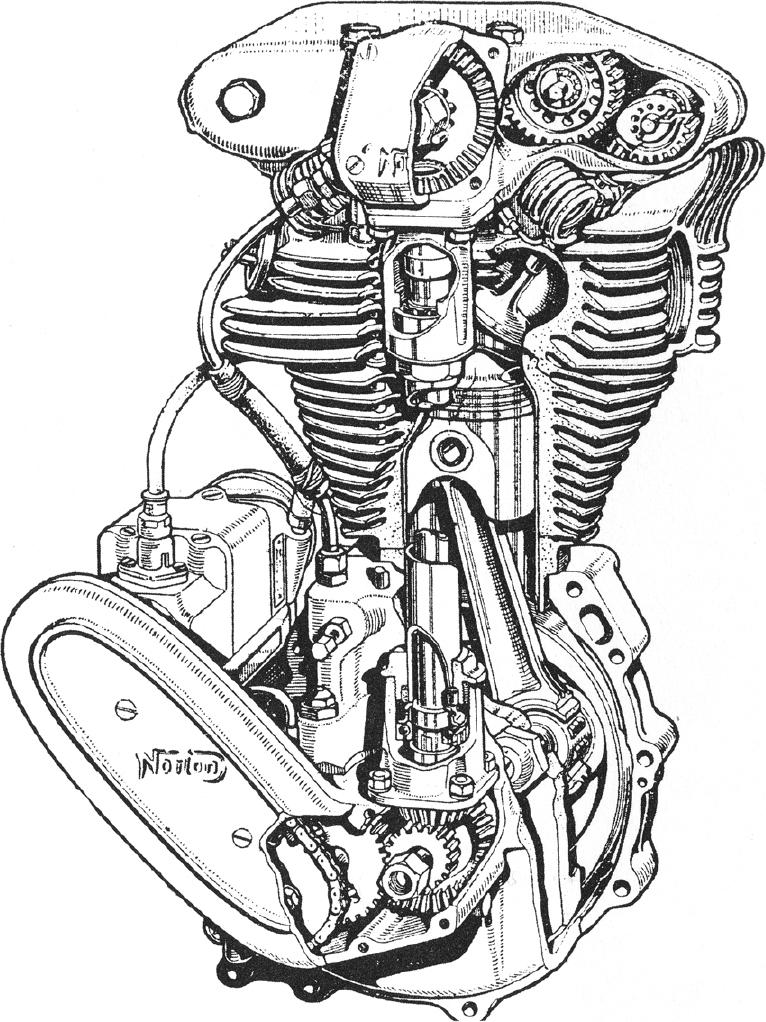

The 250cc Rudge engine that gained first, second and third place in the 1934 Lightweight TT.

The races of 1934 were good ones for Jimmy, because he also took second place in the Junior and Senior events on his Nortons. However, having taken an appointment in Shell’s competition department at the end of 1933, he decided, at the age of thirty-five, to retire from racing after the TT. The two big classes in 1934 were won by Jimmie Guthrie for Norton, so leaving the name of Stanley Woods missing from the winners for the first time in several years. Stanley had been unhappy with some of the riding-to-order requirements of Norton (setting up his own signalling system on the Island to be better informed) and, after receiving a good financial offer to ride Husqvarnas, he decided towards the end of 1933 that he would switch to the Swedish marque in 1934.

Husqvarna’s 1934 TT effort suffered a set-back even before it left Sweden prior to the event, for as a lorry loaded with 350 and 500cc V-twin racers was being loaded onto a ship at Gothenburg, a cable failed and the lorry fell to the dockside, finishing upside down. The bikes went back to the factory for quick repairs and the three Husqvarna riders – Stanley Woods, Ernie Nott and Gunnar Kalen – were late receiving their race bikes. Nott was the only one with Senior and Junior Husqvarnas; although forced to retire in the Senior, he took a fine third place in the Junior, some six minutes behind the winner.

Those who wondered if Stanley Woods had done the right thing in leaving Norton to ride for Husqvarna had their question answered when Stanley showed his machine’s quality by holding second place for much of the Senior race. Setting the fastest lap at 80.49mph (129.53km/h) in damp conditions, his threat to leader Jimmie Guthrie ended on the last lap when he ran out of fuel less than 10 miles from the finish. It was the nearest that Norton had been to defeat for several years, and it created a sense of expectation among TT fans and a feeling that the all-conquering Nortons could be challenged in future events, particularly as Walter Rusk had taken a Velocette into a fine third place in the Senior.

A Year to Remember

The 1935 TT meeting did not get off to the best of starts due to a general strike on the Island, but luckily it was called off just as most of the racers and officials, as well as tyre, petrol, oil and other trade representatives, arrived for practice. A few of the earliest arrivals had to carry their own bags to their hotels and eat cold meals by the light of candles, but most were spared such inconvenience.

The total entry of 107 comprised forty-one Senior, thirty-seven Junior and twenty-nine Lightweights, with a strong foreign challenge coming from Moto Guzzi (5), NSU (6), Jawa (5), DKW (4) and Terrot (2). The Norton team was based at the Castle Mona and was much changed, its members being Jimmie Guthrie, Walter Rusk and Johnny Duncan. Apart from those works entries there were only three other Nortons in the Senior race: ‘Crasher’ White on a factory-supported machine, plus privateers Bill Beevers and Chris Tattersall. Norton entries were also outnumbered by the small Vincent-HRD company, which had made its TT debut only the previous year, for this Stevenage concern had four works entries using engines of its own design and manufacture and also entered three JAP-engined machines on behalf of their engine maker, J.A. Prestwich. For its second year on the Island, Vincent-HRD based itself in garages at the Falcon Cliff Hotel, along with the New Imperial and NSU camps.

‘Laddie’ Courtney prepares to start in the 1935 Senior TT on a Vincent HRD with JAP engine.

Over half of the Junior entry were Velocette-mounted, which showed the worth of the company’s policy of marketing their over-the-counter KTT racer for purchase by the ordinary rider. There were also Velocette ‘works’ entries for Wal Handley, Ernie Nott, Harold Newman and Les Archer in the Junior and for the first three of those in the Senior. The magazine Motor Cycling described the Velocettes as beautifully prepared, adding ‘a black and gold finish takes a lot of beating’. Experienced TT riders George Rowley and Henry Tyrell-Smith had ‘works’ AJS entries in both Junior and Senior classes, as did up-and-coming former Manx Grand Prix (MGP) runner Harold Daniell. The eight makes represented in the Lightweight race saw entries on Excelsior, New Imperial, Rudge, Cotton, Terrot, Moto Guzzi, DKW and CTS.

Stanley Woods’s hopes of bettering his performance of 1934 with a Husqvarna were foiled by lack of entries from the Swedish concern, but he turned to the manufacturer of another V-twin, the Italian Moto Guzzi, with which to mount his Senior TT challenge in 1935. Stanley had ridden a 250cc single-cylinder Guzzi to fourth place in the 1934 Lightweight race and in 1935 he had entries on the red machines in both the Lightweight and the Senior, as did his team-mate Omobono Tenni. Based at the Majestic Hotel in Onchan, the Moto Guzzis, together with the Vincent-HRDs, were among the few machines of the day fitted with rear suspension.

After more than a week of cold early-morning practice sessions, honours were divided in all classes among the top runners from Norton, Moto Guzzi, Velocette and New Imperial. While no clear favourites emerged, only the teams themselves really knew if they were showing their best performances, or if they were holding something back. While the experienced top runners headed the practice leaderboards, those who were new to the Mountain Course put in many extra road-learning miles over open roads outside of the official practice periods. A report in Motor Cycle noted that ‘The DKW riders are out all day on their touring machines … Tenni takes a Guzzi out every day … Steinbach on the NSU does six laps in the morning and six in the afternoon every day’. Such application was very necessary if they were to be able to ride the course at racing speeds. Inevitably some newcomers tried too hard too soon and there were accidents in practice, including one to the experienced Wal Handley, and they reduced the eventual number of race starters.

Travelling Marshals

New to the TT organization in 1935 were motorcycle-mounted Travelling Marshals, whose job was to provide pre-race information to the Clerk of the Course on weather and road conditions, and to speed to race incidents and assist the static marshals at any point on the 37¾ miles of the Mountain Course. In their first year of operation they were on duty only on race-days, but this was later extended to include practice sessions. Former TT riders Vic Brittain and Arthur Simcock were the first two Travelling Marshals. They, and those who followed, became an indispensable part of the organization, being described by several of those who carried out Clerk of the Course duties in the control tower at the grandstand as acting as their ‘eyes and ears’ out on the course.

Another new arrangement for 1935 was that riders were permitted to warm their engines before the start. Most did this by riding up and down a defined section of the Glencrutchery Road near the grandstand. The consequent aromas of Castrol ‘R’ that wafted over the crowds no doubt added to the pre-race atmosphere, as did the newly introduced parade of riders to the grid behind Boy Scouts carrying the flags of the competing nations. Trying to catch some of that atmosphere was a film crew shooting crowd scenes for the George Formby film No Limit, based loosely around the TT, but the finished product must have given a somewhat distorted view to those not familiar with the races.

Familiar and Unfamiliar Results

For all the talk of a serious foreign challenge in 1935, the first race of the week – the Junior – saw a familiar Norton 1-2-3, with Jimmie Guthrie leading home Walter Rusk and John ‘Crasher’ White in damp conditions. The Lightweight TT, however, run on the Wednesday in poor weather, provided emphatic proof that there was strength in the foreign challenge, for Stanley Woods on his small Moto Guzzi rode to a comfortable win, almost three minutes ahead of Henry Tyrell-Smith (Rudge), with Ernie Nott (Rudge) another four minutes behind. It was the first TT victory by a foreign machine since the Indian 1-2-3 of 1911. Although the Lightweight race was not as highly regarded as the Junior and Senior classes, Stanley’s 500cc Moto Guzzi had been right up with the fastest runners in Senior practice and racegoers looked forward to Friday’s ‘Blue Riband’ event with eager anticipation.

Postponed

Previously every TT had gone ahead, whatever the weather, but for the first time ever the organizers decided to postpone the Senior race due to adverse weather conditions. With the growth in speeds, the occurrence of several serious accidents in poor conditions, and the round-the-course information coming in from the new Travelling Marshals – Vic Brittain reported on the Friday morning that ‘at no point on the Mountain was visibility more than 20 yards’ – the sensible decision was taken to postpone the race until Saturday.

A Sensational Race

Based on past performances, practice times and informed comment, most people expected the Senior race to be a contest between Norton team-leader Jimmie Guthrie (starting at number 1) on his finely honed single-cylinder racer, and the impressive but less well-known Italian twin-cylinder Moto Guzzi of multiple former winner Stanley Woods (starting 14½ minutes later at number 30). Guthrie was backed by a strong Norton team, but Woods was the lone Moto Guzzi runner, since his team-mate Omobono Tenni, described as ‘the most brilliant debutant the Island has ever welcomed’, was out of the race after a fall in the Lightweight.

In what was to be one of the most dramatic of TT races, Jimmie Guthrie went flat-out from the start, seemingly confident in his own ability and the reliability of his Norton to withstand such punishment for seven laps and 264½ gruelling miles. In contrast, Woods, who experienced major mechanical failure with the Guzzi in several pre-TT races, went off at a slower pace (although they both broke the lap record from a standing start!) The deficit at the end of the first lap was 28 seconds between Guthrie and Woods, with Walter Rusk (Norton) actually holding second place just one second ahead of Woods. Guthrie increased his lead to fifty-two seconds by the end of the third lap. Although Woods moved into second and was aware of the growing gap (he later told how his private telephone stations and timing staff worked perfectly to supply him with race information), he concentrated on working harder on the bends rather than risk overworking the engine, restricting himself to Carlo Guzzi’s prescribed 7,400rpm for the first two laps, increasing to 7,700rpm on lap three.

Seldom, if ever, does a rider achieve a perfect racing lap on the Mountain Course, for mistakes are made, slower riders prove difficult to pass, and so time is lost. Woods became slightly discouraged by several major hold-ups to his race progress and by the way that Guthrie, who by starting at number 1 had a clear road, extended his lead. However, vastly experienced at the TT, he kept his head. As he left his pit after refuelling at the end of the third lap, Woods weighed up his strategy for the remaining four laps.

With his signalling stations telling him that he was slowly eating into Guthrie’s lead on laps five and six, Woods’s mind was busy with mental arithmetic calculating the number of seconds that he had gained and the number that he needed to catch the flying Scotsman. Although growing in confidence, he saw that half-way around the sixth lap he was still twenty-nine seconds down on Guthrie, with a threatening Rusk (Norton) and Duncan (Norton) lying third and fourth.

Woods had told his pit attendant to be prepared for him stopping at the end of the sixth lap for a possible ‘splash and dash’ top-up of fuel. His attendant duly set about his preparations in good time, even before Guthrie came through to start his last lap. This was something that the Norton people must have noticed. Whether it lulled them into signalling Guthrie to hold his pace is not known – and whether Guthrie could have increased his already record-breaking pace is doubtful. Woods made his decision not to stop at the end of the sixth lap just after he rounded Governor’s Bridge, saying: ‘Glencrutchery Road, and a quick glance into my petrol tank to make sure that all is well’. All was well and he roared past the pits without stopping. For the first time in the race he allowed his Guzzi to achieve maximum revs in third, before changing into top beyond the pits where he got the message from his private signalling station that Guthrie’s lead was down to twenty-one seconds. That figure had been measured at his previous signalling point at Sulby, and his mental calculations as he plunged down Bray Hill at the start of his last lap suggested that it should now be less.

Would Guthrie have received a last-lap message to speed up? Woods did not know, but he did know that his last lap had to be an all-out effort and he let the revs climb to just under 8,000. Giving it everything, it was with massive disappointment that he discovered from his signalling board at Sulby that he had actually been twenty-six seconds behind Guthrie at the start of the last lap, not the thirteen or so that he had calculated. Not a man to give up, Woods let the Guzzi rev to 8,000 (118mph) on the Sulby Straight and thereafter revved it to its maximum on the stretch to Ramsey and up the Mountain climb. Coming down the Mountain he did not pay too much attention to the ever-climbing engine revolutions, for he was flat on the tank and seeking to take every corner at the fastest possible speed. Barely conscious of the massed spectators waving him on, Woods knew that, for all his efforts, he had to exercise an element of caution on the tricky bends that ran from the foot of the Mountain, through Hillberry, Cronk ny Mona, Signpost, Bedstead, The Nook and Governor’s Bridge to the finish, but he was desperate to gain time.

Flashing over the finishing line, applying the brakes hard and turning back into the Paddock, Woods was smothered by jubilant Italians. The starting interval between him and Guthrie had been 14 minutes 30 seconds and the gap at the finish was 14 minutes 26 seconds. Woods had won by four seconds with an incredible last lap of 26 minutes 10 seconds, a record-breaking speed of 86.53mph (139.35km/h).

The decision caused a degree of chaos on the crowded Island, for there were no contingency arrangements in place to cope with the effects of a postponement. Cafés and pubs filled with damp spectators seeking to dry out and consider their transport and accommodation arrangements, which had been thrown into confusion. As well as the thousands of spectators who were over for the entire race week, the Isle of Man Steam Packet Company landed an additional 11,000 race fans on the Island before 7.30am on Senior race day. As there were only four telephone lines from the Island to the mainland they were swamped with people trying to make new arrangements. Not all could, and many disappointed fans had to leave without seeing the big race.

Special approvals had to be obtained to close the roads for running the race on Saturday and, at a time when most people worked at least half the day, local marshals found it difficult to get time off work to man the course. Early inspections on Saturday morning had Travelling Marshal Arthur Simcock reporting poor visibility at the Bungalow. Aware of the considerable responsibility attached to his weather assessment, he later reported that, although visibility was still restricted, he did not consider that it would affect rider safety. The decision was taken for the Senior to go ahead, although injuries sustained by some riders in practice and the need for other competitors to honour commitments elsewhere meant that the number of starters was reduced, and only twenty-eight of the forty-one entries came to the line.

Whoops!

Few people had thought that Stanley Woods could pull back twenty-six seconds on Jimmie Guthrie on the last lap of that 1935 Senior TT. Remember, they were almost fifteen minutes apart on the road, and when Jimmy crossed the finishing line, impatient radio commentators, organizers, photographers and the Norton team were all keen to get on with the victory celebrations. It was only after much congratulatory shaking of hands, the broadcast of eulogies to Guthrie and Norton over the public-address system and the taking of celebratory photographs, that news came through of Stanley’s win. It was one that caused an all-round reddening of faces of those involved in the premature celebrations of a Norton victory.

Most post-race pictures show riders smiling for the camera, but in this one Stanley Woods shows the strain of racing to victory in 1935 on his 500cc Moto Guzzi.

While it is only natural for spectators and the press to concentrate their attentions on the winner (or supposed winner!), there were other fine performances in the Senior. Taking just under 3 hours 10 minutes for his race, Walter Rusk (Norton) finished third and John Duncan (Norton) was fourth. The first all-foreign combination was Otto Steinbach (NSU) in fifth, followed in sixth by Ted Mellors (NSU); the latter pair of entries show that other manufacturers as well as Moto Guzzi were seeking to challenge Britain’s domination of the TT races.

Although no real threat to the leaders, the Vincent-HRD concern must have been pleased to get five of its seven entries to the finish in only its second year at the TT, boosting the company’s reputation and sales.

Lessons Learnt

One year before the momentous 1935 Senior race, several experienced TT men had been asked by one of the weekly magazines to forecast the future of racing machinery. Graham Walker saw multi-cylinders, unit-construction and enclosure as ideals, Stanley Woods spoke of multis and supercharging, Charlie Dodson multis and spring frames, while Tyrell-Smith also thought the future lay with multis. In those days, the term multi was used for any machine of more than one cylinder. Of course, not every company could, or wanted to meet all such ideals, but the winning Moto Guzzi met several of them – twin-cylinders, unit-construction of engine and gearbox, rear springing – leaving the British motorcycle industry to contemplate if they were the reasons for its defeat by the Italian invader.

Technical Progress

It would be wrong to suggest that the British motorcycle industry had not improved its products during the first half of the 1930s. The TT was still regarded by manufacturers as a proving-ground for new developments, a fact appreciated by the buying public, who recognized the worth of strong (not necessarily winning) performances over the demanding Mountain Course, even though there were a few who claimed that the TT no longer had a major influence on the design of road-going machines. The early 1930s had seen advances in metallurgy that saw growing use of alloys for improved heat-shedding, lightness and durability. They were sometimes used to produce items like aluminium-bronze heads, or to give aluminium finning around a steel barrel, but were also used as direct replacements, as with elektron crankcases, hubs and alloy wheel-rims, with engine internals occasionally utilizing aluminium components.

All aspects of racing machinery were subject to experimentation and improvement. It became common for previously exposed valve-gear to be enclosed, the steels in use for frame tubing and such were improved and pressed steel frames were tried. Megaphone exhausts came into use, twin carburettors were used in experiments on single-cylinder machines, supercharging was tried, rear suspension proved its worth but was slow to be accepted, and the Cross concern utilized its own form of rotary-valve and oil/water cooling.

Riders had customarily supplemented the standard road-going saddle with a ‘bum-pad’ on the rear mudguard, which better allowed them to adopt a race posture. In the mid-1930s many adopted an elongated seat instead of the two separate fittings, and manufacturers slowly began to adopt rear suspension.

Beyond technical developments, an important topic that came to the fore in 1935 was the susceptibility of the Mountain Course to bad weather (the proverbial ‘Mist on the Mountain’), which meant that even if the poor conditions extended for only a few miles over the high ground the whole circuit could be put out of use. The pessimists correctly forecast that the first TT postponement of 1935 was the prelude to others, and Motor Cycle asked ‘whether it is not time that the ACU gave up the Mountain Circuit?’ In his book TT Thrills, the respected Laurie Cade mentions that in the mid-1930s:

The Manx Highways Board did in fact survey and produce an entirely new course, measuring twenty miles; this was claimed to have an enormous advantage in that it did not traverse the mountains, and so was not subject to the Mantle of Mona, that quickly-arising mist which sometimes enveloped the high roads.

As the 1936 TT approached it became clear that there was to be no immediate change from the Mountain Course, as the TT programme explained: ‘Although considerable controversy arose following the 1935 races, the ACU, for various reasons, has decided for this year at least, to utilise again the course that has been used for every post-war race – known throughout the world as the Mountain Course.’

Spectators

Riding on the excitement of the 1935 races, spectators from all over Europe flocked to the Island in 1936, with many foreign visitors keen to see if their riders, such as Tenni, Steinbach and Geiss, could do even better.

Opened the previous year, the Mersey Tunnel gave easier access to the Isle of Man boats to those approaching Liverpool from the south. However, one persistent difficulty for all motorcycle-riding visitors to the TT was the Steam Packet Company’s regulation that petrol tanks had to be pumped dry before loading for the unavoidable boat crossing. Motor Cycle publicized this requirement and highlighted a service for RAC members with the words:

Riders who are taking their machines over to the Island for the TT will be pleased to hear that the usual arrangements have been made by the RAC at Liverpool, Douglas and Fleetwood. RAC guides will be in attendance at these ports, equipped with quick-acting suction-pumps for emptying the petrol tanks – tanks must be drained dry of petrol before they are taken on the boats. Riders will be given a voucher which will entitle them on arrival on the other side to a small quantity of petrol, to enable them to ride to the nearest garage under power.

Riders who were not members of the RAC had their tanks pumped dry but were left to fend for themselves on landing. There was also a requirement for every rider to take out temporary registration of his bike before using it on the Island’s roads by way of an Exemption Registration Certificate. The cost for this was 2/6 (12½p) and there was a need for a temporary driving licence costing 1/- (5p).

At peak times the Steam Packet boats were completely crammed with bikes and bodies. Most of the bikes made the crossing on the open decks, with road machines often roped to adjacent competition machines that were destined for the races, for it was still the time when few factories used vans to transport bikes to the Island. Unfortunately, despite spectator enthusiasm and the effort made by everyone concerned with the races to get there, total entries for 1936 were only eighty-five, of which a mere twenty-four were for the Senior.

Consistency

Amid signs that British manufacturers were heeding both the ‘words of the wise’ and the racing lessons of 1935, unit construction New Imperials were entered in the Lightweight TT, while there were 4-cylinder supercharged AJS models for George Rowley and Harold Daniell in the Senior, plus experimental supercharged singles from Vincent-HRD, which promised much but reverted to normal aspiration for the race. Norton’s racing efforts were mostly paid for by monies from Castrol oils and for 1936 the company chose to continue with its proven single-cylinder racers, although it did adopt a basic form of plunger rear suspension on the ‘works’ entries of Jimmie Guthrie, John ‘Crasher’ White and MGP winner Freddie Frith.

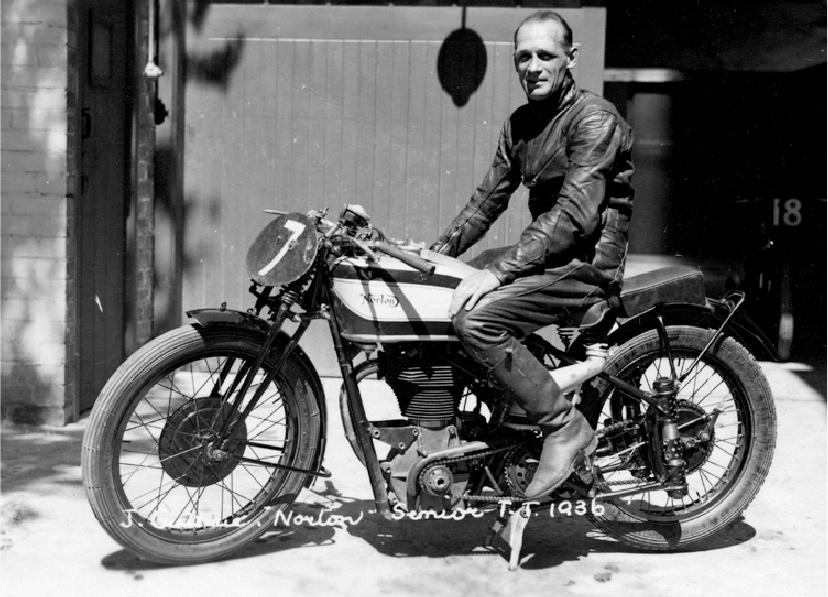

Jimmie Guthrie outside the Norton team garage during practice week in 1936 shows the new plunger rear suspension.

The Norton engines had slight alterations to bore and stroke (the ‘500’ going from 490 to 499cc). They also had increased finning to the engines, and were fitted with larger diameter brakes. Experimental double overhead camshaft engines were tried in practice but were considered to have had insufficient development time to be used at the 1936 TT.

While Norton honed their race machinery and their experience by contesting the TT every year, such consistency was lacking on the part of some manufacturers. Despite its successes in 1935, Moto Guzzi did not return in 1936 because Italy was busy waging war in Abyssinia. This meant that Stanley Woods was forced to look elsewhere for machinery and in 1936 he was entered on a DKW in the Lightweight and on ever-improving Velocettes in the Junior and Senior events. The German DKW concern claimed to be the biggest motorcycle manufacturer in the world at the time. Its TT machine was a two-stroke with a piston-pump form of forced induction, while the four-stroke Velocettes came with new pivoted-fork rear suspension aided by oleomatic units providing air springing and oil damping.

Norton teamsters Freddie Frith and Jimmie Guthrie appeared on these advertising cards issued by Castrol in the mid-1930s.

Early Risers

In 1936 practice sessions were still restricted to early mornings. For some race officials this meant getting up at 3am to prepare for such tasks as closing roads. For riders, mechanics, factory personnel and keen spectators a slightly later wakening was acceptable, and an unusual service offered in the advertising of the Falcon Cliff Hotel was ‘guaranteed practice calls at 3.45am, with refreshments’. A report of an early practice in 1936 told of Jack (C.J.) Williams being first in the queue of starters at 4.15am with his 500cc Vincent-HRD. When the course inspection and road-closing car arrived back at the start he was told ‘good visibility, lots of wind and millions of rabbits’. He was first man away, at 4.33am, knowing full well that the bark from his exhaust would awaken many nearby residents and hoping that it would also clear the course of rabbits.

Upon completion of their lap or laps riders would adjourn to a refreshment tent at the rear of the grandstand where they would find hot cocoa or coffee supplied by Cadbury’s or Dunlop. In the chill of the early morning, riders, mechanics, factory executives, trade representatives, journalists and sponsors rubbed shoulders in the damp and cigarette smoke-filled air. It was a place where first-hand information could be exchanged, machine performances discussed, sponsorship deals negotiated, plenty of tall tales told and much gossip exchanged. In the words of well-known competitor Phil Heath: ‘Practising was great fun. There was nothing to beat the excitement of a couple of laps in good weather with the bike running well and the prospect of a chinwag and hot cup of cocoa at the end’.

Riders take refreshment after early-morning practice.

Lightweight Variety

The 1936 meeting saw the Lightweight TT attract the greatest number of entries with thirty-four riders competing on ten different makes of machine. Having been very influential in this class in the early 1930s, the Rudge concern had managed to weather severe financial difficulties but it could no longer afford to support a race team and only one privately entered 250cc machine carried the Coventry firm’s name on its tank. Other entries were mounted on New Imperial, Excelsior, Cotton, O.K.-Supreme and, worryingly for those British makes, there were three ‘works’ DKWs that proved very quick in practice.

With the race postponed from Wednesday to Thursday owing to poor weather conditions, thirty-one riders presented themselves for the 11am start. All races had moved from a 10 to 11 o’clock start-time in order to allow more time for mist to clear from the Mountain. Also, as an aid to visibility in poor conditions, a yellow line was painted along the middle of the Mountain Road from the Gooseneck to Creg ny Baa, while the flattening and widening of Ballig Bridge was believed to have saved riders between three and five seconds a lap.

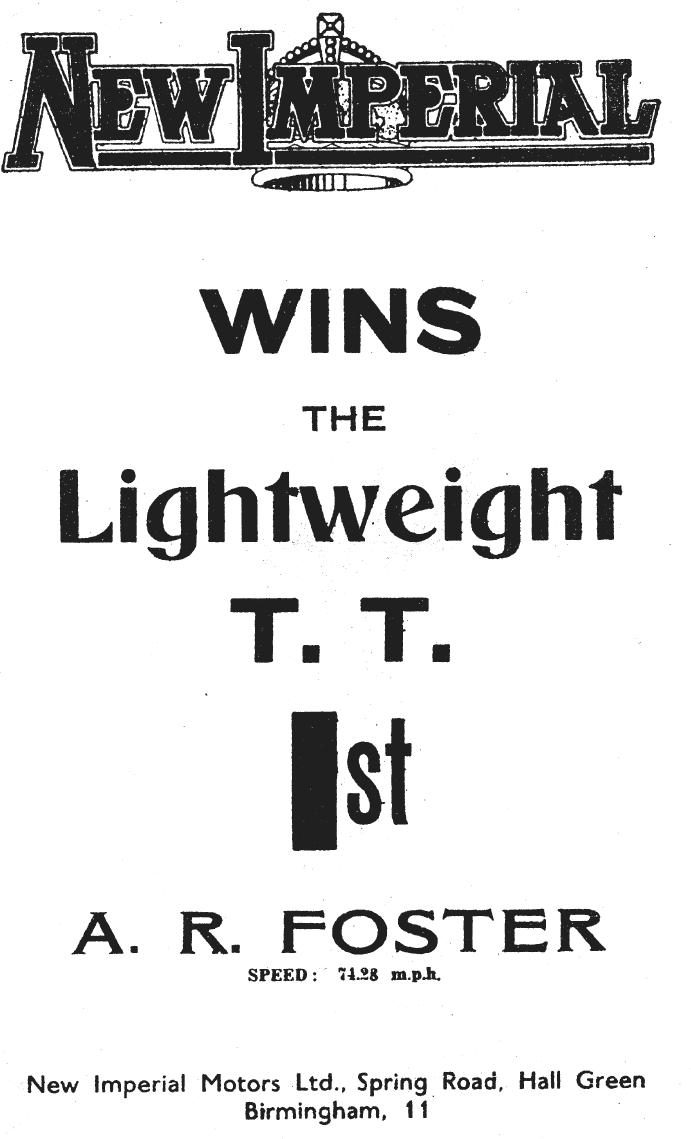

Few were surprised when the talented and vastly experienced Stanley Woods (DKW) took an early lead in the Lightweight race, but they were impressed to see newly married Bob Foster (New Imperial) holding second place, for Bob had much less experience over the Mountain Course. Woods was well ahead of the other DKW riders, but Foster had Jack Williams (New Imperial) and Henry Tyrell-Smith (Excelsior) chasing him for second place. Foster moved ahead of Woods on the third lap when the DKW rider stopped out on the course to replace a plug. Both men refuelled at the end of the third lap and, catching spectators by surprise, the surviving DKW riders, Woods and Geiss, stopped again at the end of the fourth lap to top up their thirsty two-strokes for the three-lap run through to the finish. Quite the noisiest machines to have been heard at the TT, Motor Cycling mentioned the DKW of Geiss ‘going like a scalded cat – and making quite as much noise!’ Although Woods regained the lead for the fourth and fifth laps he had further plug trouble and that allowed Foster back into the lead. Passing his pit at the start of his seventh and last lap, Stanley gave a brief thumbs-down to his crew. Foster, still believing that the speedy Stanley might catch him, rode to the limit of his own and his machine’s performance to take a very popular, record-breaking victory, so recovering the Lightweight Tourist Trophy for Britain. With Woods forced to retire on the Mountain during the last lap, Foster had five minutes in hand over second-place Tyrell-Smith (Excelsior), but the latter was only three seconds ahead of Geiss (DKW).

With unit-construction and gear-driven primary drive (as on the company’s lightweight roadsters), Bob Foster’s machine broke fresh ground for a British racing machine, moving New Imperial Motors Ltd to advertise its TT success with the statement: ‘Unit-Construction is the most up-to-date feature in modern motorcycle design’. Unfortunately, the company was not able to advertise similar success with its V-twin in the Senior, where ‘Ginger’ Wood was forced to retire on the last lap when lying in fifth place, and the New Imperial racing team folded later in 1936.

New Imperial’s celebrations of their victory in the 1936 Lightweight TT included this advertisement and the transfer they added to the petrol tanks of their road bikes.

In both big classes at the 1936 TT Norton headed the practice leader-board, but some experienced observers felt that Veloce Ltd stood a chance of victory in the Junior, where riders of its Velocette models were Stanley Woods and Ernie Thomas. But on race-day it was Norton machinery that led the way home, with former MGP winner (but first-timer at the TT) Freddie Frith winning at record speed from his team-mate ‘Crasher’ White, and with Ted Mellors (Velocette) third. Although Jimmie Guthrie led the race for the first four laps and looked set to win, a stop near Hillberry to refit a drive chain cost him time and created a clash with the organizers over whether he did or did not receive outside assistance in restarting. It led to the submission of an official protest from the Norton camp that was somewhat unsatisfactorily resolved by allowing Guthrie to retain his fifth finishing place but being paid the same prize money as White in second place.

Guthrie made no mistakes en route to winning the Senior, which he led throughout despite being closely pursued by Stanley Woods (Velocette). In what was the Velocette company’s best Senior TT performance to date, Stanley failed by just eighteen seconds to catch the flying Scotsman, although in doing so he set the fastest lap of the race and beat his own record of the previous year. He was also left wondering what might have been, had his Velo’ not developed an intermittent misfire on the last lap that knocked the edge off his speed. So, in 1936 single-cylinder machines again dominated the Senior; AJS’s attempt at ‘progress’ with its supercharged 4-cylinder racers was unsuccessful, for the mounts of Rowley and Daniell were heavy, did not handle well and were plagued with carburation troubles.

George Rowley speeds towards Keppel Gate on his 4-cylinder supercharged AJS during the 1936 Senior TT.

Truly an island of speed, just before the TT a ‘round-the-houses’ car race in Douglas attracted many of the top names of the day. The Island was also part of a major air race that started from London and finished at Ronaldsway. Immediately following the motorcycle TT came the ‘Bicycle TT’ run over the same Mountain Course. Proving rather more dangerous than motorized racing, ten of the eighty push-bike competitors finished up in hospital.

Rumbles

Despite its high standing with the majority of road race supporters, the TT has always been a target for criticism – often from those who were not winning or had personal axes to grind. Right in the middle of the 1936 TT, the influential magazine Motor Cycling floated the proposal that it should be the last year of the races in their present form, that a shorter British Grand Prix should be held in England (could it have been speaking on behalf of Donington?), and that the TT should revert more to a long-distance reliability Trial format, for production-based machines.

It was common knowledge that an ACU sub-committee was already considering the topic of the TT Mountain Course, spurred by the problems caused by poor weather and postponements. Manx newspapers joined in the discussion, with the Isle of Man Weekly Times rating a move of the TT from the island ‘nothing short of a calamity’. It put forward proposals for a new 8-mile course to be covered thirty times, which it believed could be learnt in two practice sessions. In doing this it recognized that the Mountain Course with interval starts was ‘too long to hold the interest of a sensation-seeking public’.

Norton’s dominance of the TT (and foreign Grand Prix) continued to rankle with some. There were even suggestions that the company should abstain from competing at the TT to give other manufacturers a chance. The Manx press had a view on this too, saying ‘the supremacy of the Norton machines has been, to some extent at least, responsible for the decline in entries’. Norton had achieved sixteen TT wins, but what a hollow victory it would have been for another manufacturer if Norton had withdrawn from the TT in order to give others a chance. On the other hand, what wonderful publicity it would have generated for the Bracebridge Street manufacturer and its ‘Unapproachable’ machines!

In truth, the performance gap between Norton and other makes had closed, but Joe Craig was very aware of this and worked hard during the winter to extract more from the Norton single-cylinder powerplant. The biggest change for the 1937 TT was the use of double overhead camshaft engines, with a train of five gears in the head replacing rockers. Craig claimed measurable extra power from the 500cc race engine with the dohc arrangement (less benefit from the 350), which had been well tested during the latter part of 1936. He had become a well-seasoned race manager, making haste slowly with new developments and used to juggling highly tuned race machinery and riders to get the best results. Of the latter he said: ‘in some cases and in certain circumstances, the riders can be as temperamental as the machines usually are’.

Nicknamed ‘The Wizard of Tune’, this was how Sallon saw Norton’s Joe Craig.

Back to Normal?

When entries closed for the 1937 TT they were up to 103 (from 85) and talk of moving the event from the Mountain Course or changing the nature of the races had seemingly subsided. What the Isle of Man did not know, however, was that during the period of the 1937 races the organizing ACU was actually ‘negotiating with an English municipality with a view to having the races run in another area’. Ignorant of these behind-the-scenes manoeuvrings, riders from thirteen countries looked forward to competing in the traditional TT races, with all that meant in terms of getting to learn (or relearn) the 37¾-mile course during the extensive period allowed for practice.

One change to the practice arrangements was the introduction of the first evening session. This took place on the second Thursday between 6.30 and 9pm and was introduced to let competitors see how their engines performed in conditions nearer to those that they could expect in a race, for the customary early morning sessions often did not allow for optimum carburation tuning. Evening practice proved more accessible to the local population and the Manx turned out in large numbers to watch in excellent weather, with Jimmie Guthrie (Norton) unofficially breaking Stanley Woods’s 1936 record lap by fifteen seconds. With Freddie Frith also beating his own Junior lap record in practice, spectators looked forward to fast racing in all classes, particularly as the Lightweight Moto Guzzis of Stanley Woods and Omobono Tenni, plus the DKWs of Ewald Kluge and Ernie Thomas, were reported to be capable of over 100mph (160km/h).

Race week started with the customary Junior event on Monday, and Stanley Woods’s race had barely got under way when he had a frightening near-miss with a stray dog at the foot of Bray Hill. But it was the Norton team that quickly established its superiority over the opposition: the final result was Guthrie, White and Frith (Nortons), with Woods (Velocette) taking fourth place. The high speeds promised by practice week were realized in the race when Guthrie and Frith both broke the Junior lap record with identical times of 26 minutes 35 seconds, a speed of 85.18mph (137.08 km/h), comfortably beating Frith’s 1936 record lap of 81.94mph (131.87km/h).

An example of the all-conquering Norton single-cylinder engine of 1937 with double ohc.

Wednesday’s Lightweight race also saw the establishment of new race and lap records. It was one that had three different leaders, the first being Ewald Kluge (DKW), but he soon lost first place to Stanley Woods (Moto Guzzi) before retiring his two-stroke with a broken throttle cable. Woods eventually lost the lead on the sixth lap to Guzzi team-mate Omobono Tenni. Both Woods and Tenni gave a thumbs-down signal to the Moto Guzzi pits as they went through to start their last laps. Stanley’s problem proved terminal at Sulby but Tenni, although he stopped to change a plug, continued his race and took victory from ‘Ginger’ Wood (Excelsior), Ernie Thomas (DKW) and Les Archer (New Imperial). There was much jubilation in the Moto Guzzi camp at the first victory by an Italian rider on an Italian machine, and Signor Parodi, a director of the company, wired the news to Mussolini.

Friday, Senior race day, dawned with fine weather for what turned into a titanic contest between Norton and Velocette. It was team leaders Jimmie Guthrie (Norton) and Stanley Woods (Velocette) who contested the lead for the first four laps, with Freddie Frith (Norton) pulling through the field to threaten them. Guthrie retired on the fifth lap, but Woods and Frith continued at a tremendous pace and started the seventh and last lap tying on time for first place. Woods rode at number 4 and Frith at 24, so the race was a classic TT battle on time, with the contestants miles apart on the road. Pushing his Norton harder than one had ever previously been ridden at the TT, Frith reached the finish fifteen seconds earlier than Woods on corrected time. Such was the race pace that he became the first man to lap at more than 90mph (90.27mph/145.27km/h), he broke Jimmie Guthrie’s 1936 Senior lap record by almost a minute, and he completed the 264½ miles in five minutes less than the previous fastest race time. It was a contest, however, in which the Velocette machines from Hall Green pressed their Birmingham counterparts from Bracebridge Street harder than ever before. Though overall victory still eluded Veloce Ltd, through Woods, Mellors and Archer it took the team prize from Norton Motors.

Stanley Woods shows the heavily finned engine of his Velocette at the 1937 TT.

A lone ‘works’ rider in the Senior was Jock West. He was mounted on a horizontally opposed, twin-cylinder, supercharged, shaft-driven BMW with telescopic front suspension and plunger at the rear. After a steady race that showed the bike’s handling needed developing to cope with the bumps of the Mountain Course, Jock came home in sixth place in what was the BMW company’s first TT.

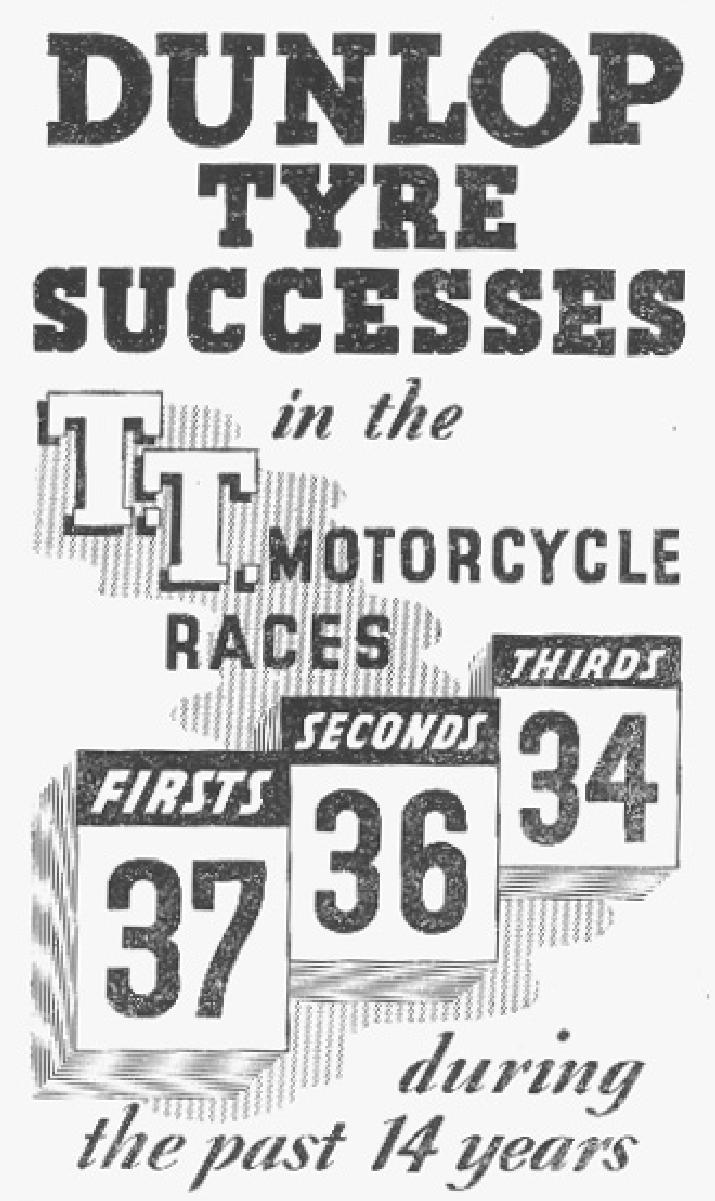

One firm that had an exceptionally successful TT in 1937 was Dunlop Tyres, a great supporter of the races. Best known for supplying tyres and providing a fitting service, they also supplied rims and wheel-building, saddles, copious supplies of rubber bands, French chalk, rider hospitality and publicity banners. At the end of the meeting the company was pleased to advertise that its products had been used by the first three place-men in Senior, Junior and Lightweight races.

Political Overtones

The TT races have always offered the opportunity for participants to escape the wider problems of the world by spending a fortnight in a high-octane atmosphere aimed solely with getting men and motorcycles to circulate the Isle of Man Mountain Course at maximum velocity. Indeed, prior to a mid-1930s TT meeting Motor Cycle captured the prevailing attitude with: ‘Who cares what Hitler says, or whether there has been another coup in the Balkans? This week we don’t read the national papers – we live, dream and read motorcycles.’ At the 1938 event, however, it was impossible to avoid the overtones of impending war and there was a strangely unreal feel about going motorcycle racing at a time of such tension. As the island gave a sporting welcome to BMW and DKW TT teams (just as it had to German pilots in the preceding week’s international air race), Britain was openly preparing for war. A local newspaper identified the anomalous position between racing and real-life activities, posing the question ‘Why are we in England working day and night in our armament factories, arranging to evacuate women and children from London at a moment’s notice, adopting all sorts of methods for saving our population from being bombed to pieces…?’

Why so Named?

The Guthrie Memorial

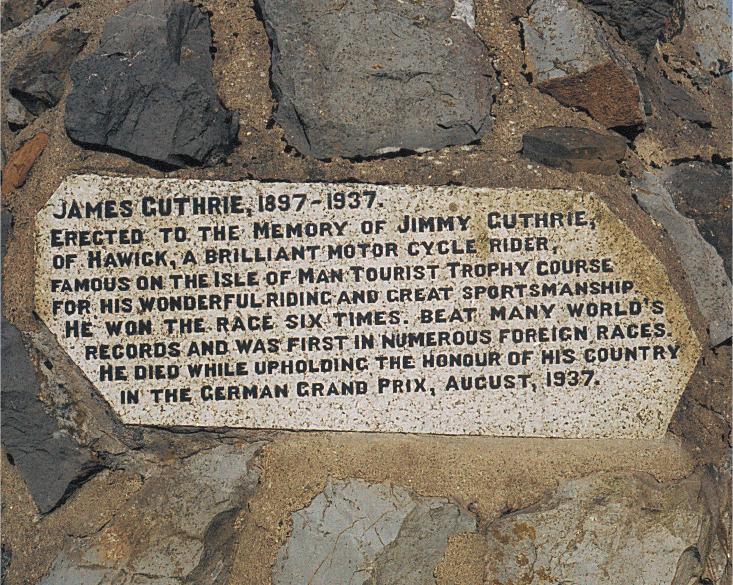

Jimmie Guthrie was known throughout the motorcycle world, for not only was he a great TT rider but he was also the winner of many Continental Grand Prix. It was during a ride in the 1937 German Grand Prix that Jimmie lost his life in a racing incident.

The inscription on the Guthrie Memorial.

Winner of six TT races in the 1930s and placeman in many others, Jimmie is remembered on the island by a stone cairn located between the 26th and 27th milestones on the Mountain climb where he retired in his last TT. Monies were raised by public subscription organized by Motor Cycle magazine and the place-name Guthrie Memorial was adopted for that spot on the course earlier known as ‘The Cutting’.

Manx Influence

Almost 50 per cent of the 109 entries in the 1938 TT were from competitors who had formerly competed in the Manx Grand Prix (MGP), a race for up-and-coming racers held over the Mountain Course in September of each year. It is an event that still breeds TT winners and it was just nine months after his double win in the 1937 MGP that Maurice Cann was entered for his first TT. He was on a Velocette in the Junior and an Excelsior in the Lightweight; through no fault of his own, however, it was to be more than a decade before Maurice achieved the TT win of which his earlier MGP wins had hinted he was capable.

There was only one true Manxman entered in the 1938 TT – Harry Craine – but there were several other competitors riding with ‘Manxman’ after their names, for they were mounted on Excelsior models that the factory had christened ‘Manxman’.

While Manx-born competitors were rare in the TT at that time, some 300 locals turned out to marshal and help run the races which, while organized in the name of the ACU, relied very heavily on local input in all areas.

An increase in the number of evening practice sessions to two received the support of riders and Manx people, particularly as the organizers decided that there would be no practice on the morning following an evening one, thus giving everybody a lie-in. This was particularly welcome in 1938 when many early-morning sessions suffered atrocious weather, seriously hampering riders’ efforts to prepare for racing. It generated some lobbying for daytime practice, which, if granted, would clearly impact on the everyday lives of local people even more than morning and evening sessions.

The 1938 Races

Good weather greeted riders and spectators for the opening Junior race, although there was some low cloud on the Mountain. Only two foreign makes had been entered, but since they did not come to the start the thirty-nine machines that went through the warming-up process on the Glencrutchery Road were all British, comprising nineteen Nortons, fifteen Velocettes and five AJS. Warming-up should have been a straightforward activity, for the organizers placed a line of metal dustbins down the centre of the road and competitors rode down one side, turned at the end and returned up the other side. Unfortunately – and not for the first time – there was a collision between two riders during the warm-up and C.B. Sutherland’s bike sustained damage to the frame that forced him to withdraw from the race.

Riders were required to cut their engines fifteen minutes before the 11 o’clock start time. They then went through the procedure of changing to harder sparking-plugs and parading to the line behind Scouts carrying their national flag. After that they sat fiddling with goggles, gloves, petrol taps and so on, while nervously awaiting to be started at half-minute intervals. When the starting maroon sounded and the flag dropped at 11am it was the Velocette pairing of Stanley Woods and Ted Mellors who soon moved into the lead. Freddie Frith (Norton) was their nearest challenger during the race, but at the finish he had to settle for third place, ahead of his team-mates Harold Daniell and ‘Crasher’ White. All three were on substantially ‘improved’ machines that, despite having been lightened and fitted with telescopic front forks, recorded slower race speeds than the previous year. The winner, Stanley Woods, reported a trouble-free run in which he broke the lap record but left the race record intact. It was the first TT win by a Velocette since 1929 and was just reward for the company’s sustained race efforts through the 1930s.

Having earned the reputation of being fast but temperamental, the DKW team managed to get one machine to the finish of the Lightweight race – in the all-important first place. Ewald Kluge battered the record book and the opposition on his way to recording the German company’s first TT win, setting a race average speed of 78.48mph (126.30km/h) and a fastest lap of 80.35mph (129.31km/h), both figures being some 5 per cent faster than the existing records. Excelsiors proved their reliability by finishing in the next six places, but second-placed ‘Ginger’ Wood was over eleven minutes behind Kluge in a race time that was slightly slower than his second-place finish in 1937. DKW had clearly leap-frogged the Lightweight opposition in the performance stakes, while Excelsior had stood still.

Despite the general apprehension about impending war, there was little reservation in the Manx press or the national motorcycle magazines about entertaining German men and machines at the TT. Their practice efforts were fairly reported and the thoroughness they showed in all aspects of preparation was openly admired. What was of serious concern was that the ‘Blue Riband’ Senior TT might well be won by the flat-twin BMWs from Germany. Its team of Georg Meier, Karl Gall and Jock West was a formidable one on paper, particularly with the exceptional speeds recorded on the Sulby Straight from their supercharged engines rated at more than 60bhp. Unfortunately, for all their apparent thoroughness, Gall put himself out of contention with an out-of-hours crash in practice week, and Meier went out on the first lap of the race with engine trouble, leaving just Jock West to participate on the fringes of the epic battle between single-cylinder runners from Norton and Velocette that occurred at the head of the Senior race.

At the end of the first lap just thirty-three seconds covered Freddie Frith (Norton), Stanley Woods (Velocette), ‘Crasher’ White (Norton) and Harold Daniell (Norton). Woods took the lead on the third lap from Frith and Daniell, with the latter then equalling the lap record on the fifth lap and tying with Frith for second place, the two Norton runners being just three seconds behind Velocette-mounted Woods. With a reputation for getting faster as a race progressed, Daniell broke the 25-minute barrier on his sixth lap to take the lead and leave Woods and Frith, both previous Senior winners, tying for second place five seconds behind him. Neither could match the pace of the bespectacled Daniell, who, knowing he had only a slender lead, went even faster on the last lap, setting a new absolute lap record of 91.00mph (146.45 km/h) and finishing fifteen seconds ahead of Woods, who was a mere 1½ seconds ahead of Frith. ‘Crasher’ White’s fourth place ensured the team prize went to Norton and by coming home fifth, Jock West salvaged some pride on behalf of BMW.

Bill Beevers flies his Norton over the St Ninian’s crossroads, prior to wrestling it down the bumpy Bray Hill and another TT lap in 1938.

Stanley Woods

Born in Dublin in 1903, Stanley Woods was probably the greatest TT rider of his era. Making his first visit to the Island in 1921, he returned to compete in 1922 and then took his first win in the 1923 Junior on a Cotton. Thereafter he was a consistently highly placed finisher, riding Royal Enfield, New Imperial, Norton, Husqvarna, Moto Guzzi, DKW and Velocette machines, with which he took TT wins against such high-calibre opposition as Charlie Dodson, Jimmy Simpson, Ernie Knott, Jimmy Guthrie and Freddie Frith.

Stanley was a thinking rider who devised his own signalling system at the TT to augment the single signal that riders received at the end of a lap, and which was already a lap out of date. His racing career included many wins in premier Continental races, and the ten TT victories he had achieved by the time he finished racing in 1939 put him at the head of the winners’ list for nearly thirty years.

A regular post-war visitor to the TT, Stanley took part in several Laps of Honour, his last ride being in 1982 when he was seventy-nine.

Stanley Woods portrayed by ‘Sallon’.

A Bumper Entry

The TT race regulations published in February 1939 were little changed from the previous year’s. The entry fee for individual events was £10, prize money totalled £1,800, and evening practice sessions had grown to three. There were still six early morning sessions.

Dunlop Tyres hoped to add to its impressive score of TT successes. This advertisement is from the 1939 TT Programme, which also contained an advertisement offering travel by air for visitors, while Motor Cycling announced that it was still running its combined rail and sea excursions to the Senior.

It may have been that competitors sensed this was to be the last TT for some years, for they flocked to pay their entry fees to this historic competition. Finally closing at 147, the total number of race entries was almost 40 per cent up on the previous year. Containing fifty-one Senior, sixty-five Junior and thirty-one Lightweights, the entry list saw an even stronger German contingent than in previous years, with BMW and NSU entries in the Senior, DKW and NSU in the Junior, and DKW in the Lightweight; many of their machines were supercharged. There was also a ‘dark horse’ from Italy, with a Benelli entered in the Lightweight along with Moto Guzzi. Although needing the best possible machinery to counter this enhanced foreign challenge, the ‘works’ Norton riders were handicapped by having to ride 1938 models without factory back up, as the company was concentrating all its production effort on Government contracts. The Velocettes were still sporting girder front forks (although they did bring their supercharged twin-cylinder ‘Roarer’ to try in practice), and Walter Rusk’s portly water-cooled and supercharged AJS V4 weighed in at 100lb (45kg) heavier than the BMWs. The overall strength of entry, however, moved a local newspaper to write: ‘The 1939 TT will be an unquestioned success, but we prefer not to speculate on TTs in 1940 and onwards.’

Sadly, the BMW challenge was reduced to two riders when Karl Gall died from injuries sustained in a practice-period crash at Ballaugh. His team-mates decided to race on and their practice performances showed they would be serious contenders for race honours, with Jock West timed at 130mph (209km/h) for a measured mile at Sulby and Meier finishing practice at the head of the Senior leader-board.

How the Isle of Man Weekly Times saw the opposing forces lined up to contest the 1939 TT.

Race week in 1939 started with the customary Junior event, which saw Stanley Woods take a narrow victory for Velocette over the Norton of Harold Daniell at slightly under record pace, with Heiner Fleischmann (DKW) in third place. It was Stanley’s tenth win in his seventeenth successive year competing in the TT. Two days later he set the fastest lap at 78.16mph (125.78km/h) on his Moto Guzzi in the Lightweight race before retiring and letting team-mate Omobono Tenni into the lead, only to see him retire on the third lap. Ted Mellors deliberately restrained his pace in the early stages, believing that the Guzzi teamsters would not last the pace, and brought his speedy little Benelli to the front on lap three. He held the position to the end, so giving the Italian firm a TT victory on its first Island appearance. Unable to match his pace of 1938, Ewald Kluge on his DKW was nearly four minutes behind Mellors at the finish and only two minutes ahead of Henry Tyrell-Smith on an Excelsior, although poor weather contributed to restricting speeds.

This memorial plaque to Karl Gall is located just after Ballaugh Bridge.

With weather and road conditions perfect for Friday’s Senior, Britain’s worst fears came true when Georg Meier and Jock West headed the field throughout the race and came home in first and second places on their BMWs. Not only did this offer the German government-backed effort a useful propaganda coup, it also earned BMW the right to take the Marquis de Mouzilly St Mars’ splendid Senior Tourist Trophy away with them. Three months later all sporting pretensions were put to one side as the principal opposing TT nations – Britain, Germany and Italy – went about the dirty business of war.

Georg Meier and his supercharged BMW in front of the pits in 1939.