With the arrival of the year 2000, the word millennium was much heard. In a world full of pundits looking at what life would bring in the years ahead, the TT received its share of consideration and predictions. Those whose interest lay solely in the racing turned their thoughts to who would be the TT’s Millennium Man over the Mountain Course, while those taking a broader look wondered for how many years into the next millennium the TT would continue to be run. On the latter point there was optimism that it would survive to celebrate its centenary in 2007, but those of a pessimistic nature saw the date as a potential cut-off point. When quizzed, many were unclear why they felt that way, but then throughout its life the TT has been faced with people trying to write it off. The strange thing is that it was often enthusiasts for the meeting who showed the most pessimism.

What was good to see was that the Isle of Man authorities were full of enthusiasm for the future, and the Minister for Tourism, former MGP competitor David Cretney, flung his weight behind making the TT Festival ever more successful. Rider and spectator interest ran at high level for 2000, for the races paid excellent prize money and the ancillary entertainment was extended to include several nights of street parties. The result was that 721 entries were received from twenty countries for the ten races, and newspaper headlines reflected increased interest and growth in televised transmissions of races, saying: ‘500 million will tune in to watch the TT’. Top road-race specialists like Joey and Robert Dunlop, Jason Griffiths, Ian Lougher, James Courtney, Adrian Archibald, Gary Dynes and Richard Britton were joined by riders who also spent much time racing on the short circuits, including David Jefferies, John McGuinness, Michael Rutter and Iain Duffus. There were also young racers coming through like Richard ‘Milky’ Quayle and Ryan Farquhar, while quality Commonwealth riders Blair Degerholm, Shaun Harris, Bruce Anstey, Paul Williams and Brett Richmond promised to help make a bright start to the millennium. Even with such a wealth of racing talent in contention, however, no one was prepared to bet against ‘King of the Roads’ Joey Dunlop celebrating the millennium with another TT win.

Practice

First practice of 2000 was on the opening Saturday evening of the fortnight. It was a departure from the normal timetable that usually saw newcomers making their racing acquaintance with the course in the cold light of Monday’s dawn, when damp roads and visibility problems were most likely to occur. This change enabled the organizers to reduce morning practice sessions to just two. Most welcomed the move, although others saw it as a step towards removing a unique aspect of the TT (and MGP) meetings for both riders and spectators. Among the newcomers in 2000 were the Argentinian riders Walter Cordoba and Eduardo ‘David’ Paredes, who had both followed the races for many years in press reports, satellite TV broadcasts and videos. They were now the first from their country to have the opportunity to fulfil their Island dreams and race over the Mountain Course.

Riders queue on the Glencrutchery Road, ready to start a practice session.

Joey Dunlop was once again riding for Honda, but this year on an SP1 V-twin (and Fireblade transverse-four, if required), with John McGuinness also receiving full ‘works’ support and Iain Duffus, Jim Moodie and Adrian Archibald giving Honda strength in depth on new race versions of the Fireblade. These had received very little testing, but were built to show that Honda’s top road bike could go head to head with Yamaha’s R1. In response, Yamaha advertised that its highly successful YZF-R1 model was ‘sharper, quicker and lighter’ in its new form, and it had David Jefferies and Michael Rutter riding examples prepared by V&M Racing.

Suzuki celebrated the fortieth anniversary of its first appearance at the TT with a tented display in Nobles Park, but gave little direct support to the racing.

125mph Lap

Talk of a 125mph (201.17km/h) lap in 2000 almost became reality in practice week when David Jefferies (Yamaha) twice went over 124mph, and spice was added to the proceedings when Adrian Archibald (Honda) became the first to lap at over 120mph (193.12km/h) on a 600. Practice times are of importance to riders and teams but they mean little to the organizers, who only recognize as official times set in a race and therefore worthy of entry in the record books. Joey Dunlop had a rather more troubled practice than Jefferies, having to cope with a stuttery power delivery and finding that the new SP1 did not handle well over the Mountain Course and that, as he described, ‘it won’t stop shaking its head’. Making a multitude of changes to fork and rear suspension settings, Joey and the other riders lost valuable practice time to bad weather in the latter part of the week, and the 48-year-old must have approached race day with reservations about fighting his Honda over 226 racing miles.

Joey Dunlop was extremely versatile, riding and winning on everything from 125s like the one shown here to Honda’s biggest racers.

By the time of the last practice scheduled for Friday evening, many riders were desperately short of track-time to get their bikes set up properly, and some still needed to complete more laps in order to qualify to race. Travelling Marshals’ reports of low cloud and generally wet conditions had the organizers in a quandary on that Friday evening, for while they wanted to run the session, the safety of competitors and the problems associated with using the rescue helicopter in poor visibility had them in two minds. Travelling Marshals were in almost constant motion on the course seeking information for Race Control. Eventually it was decided to allow the solos to run in an untimed session, with the sidecars to follow, but when it came to the sidecars’ turn even lower cloud from the Gooseneck to Kate’s Cottage put their session in jeopardy. In a compromise move, since the first Sidecar race was due to run the following day and competitors wanted to bed-in new tyres, chains, brake-pads and the like, the chairs were allowed to run at racing speed on the 23 miles from the start to Ramsey, where they were red-flagged. The forty or so outfits that had taken advantage of the restricted session were then escorted in convoy by Travelling Marshals across the misty Mountain and down to the finish at Douglas.

With Dave Molyneux away competing in the World Sidecar Cup, Rob Fisher started as favourite and duly won both Sidecar races with his Honda-powered outfit that had Rick Long in the chair. Although they averaged just under 110mph in both races, Molyneux’s race and lap records remained intact.

For all the talk of rising stars for a new millennium, it was a multi-TT winner of the old one, Joey Dunlop, who collected win number twenty-four in Saturday’s opening race of 2000, the prestigious Formula I event. The next solo race, the Lightweight 250, was on Monday, and the winner was Joey Dunlop. Wednesday morning brought another solo race, and the winner was Joey Dunlop. Race week was only half over and Joey already had a hat-trick of wins, bringing his total to twenty-six. What a man!

On the Wednesday afternoon it was David Jefferies’s turn to win a race for Yamaha by taking the Junior at a record race average speed of 119.13mph (191.72km/h), while Adrian Archibald (Honda) set the fastest lap at 121.15mph (194.97km/h). In abysmal weather on Friday morning, Jefferies rode to a second victory in a Production race shortened to two laps at 99.34mph (159.87km/h), with Manxman Richard ‘Milky’ Quayle second.

That poor weather caused postponement of the Senior to Saturday, when perfect racing conditions allowed the young Yorkshireman to also make it a hat-trick of wins for the week. It was a race in which he averaged 121.95mph (196.25km/h) and became the first to break the 125mph barrier with a record lap of 125.69mph (202.27km/h). His speed equated to a lap time of 18 minutes 0.6 seconds and was a pace that fellow hat-trick man and third-placed finisher Joey could not match even though he tried. Indeed, so hard did Joey try that he set his fastest ever lap of the TT course at 123.87mph (199.34km/h).

2001

Everyone knew that without Joey Dunlop’s presence the TT of 2001 was going to be very different from those of the previous twenty-five years in which he rode and won, but it was not until the spring that people realized just how different a year it was going to be. Large parts of Britain were ravaged by a foot and mouth epidemic and the Isle of Man, with its large farming community, was desperate to prevent the disease spreading to its shores. After much consultation, the decision was taken to cancel the TT meeting. It was a hard one to make, but the prospect of 40,000 visitors being dispersed for a fortnight of racing and practice around the fields that bounded the course was a risk that was too great to take.

No More Joey

Joey Dunlop was an enigma to many throughout his career of twenty-six TT wins, five Formula I World Championships, and countless victories at the Ulster GP and NW200. An unassuming star who was the peoples’ hero back home in Ireland, on both sides of the border, he was protective of his family. Throughout the 1990s he showed his concern for others by making many unpublicized trips to eastern Europe taking essential supplies to the needy. Honoured with an MBE and an OBE for his services to motorcycling and charities, he was a respected star on the world motorcycling scene who just loved to race motorcycles. A month after the TT he packed a couple of bikes in a van and set off to Estonia to take part in a small race meeting. There, on a rain-soaked track wending its way through a forest, he left the road on his 125, hit a tree and was killed.

It is doubtful if the world of motorcycling had ever been so united in sorrow as it was after Joey’s death, and an estimated 50,000 people turned out for his funeral in Ballymoney. The MGP took place on the island some six weeks after his death and, in an unforgettable tribute, five thousand motorcycle-mounted fans did a lap of the closed roads of the Mountain Course in his honour. Bikes of every size and description travelled at ordinary speeds over the same roads that he had covered so many times while racing to twenty-six wins – and with only one small spill.

This memorial to Joey Dunlop is located adjacent to the former Murray’s Motorcycle Museum near the Bungalow. Astride a Honda, Joey looks over the Mountain Course and up to Hailwood’s Height, named after another multi-TT winner who met an early death away from the Island, Mike Hailwood.

Ordinary visits were allowed and some 12,000 race fans came for a non-racing holiday, but the absence of a proper fortnight of racing brought home to local businesses just what it meant to miss out on their busiest two weeks of the year. The Manx Government felt it necessary to introduce compensation schemes for those who had suffered loss, and it was noticeable that among those in the queue for a hand-out were the island’s biggest hotels.

But not all Isle of Man businesses seek just to take from the TT. Several sponsor individual races and some sponsor riders, either directly with cash and machinery, or indirectly through giving free accommodation in hotels or private houses. A joint sponsorship deal that caught the eye with bikes and riders turned out in corporate colours was that between Lloyds TSB Bank (Isle of Man) and the enthusiastic Alan and Mike Kelly of Mannin Collections. It is not every bank that sponsors a TT rider, but as Andy Webb, Island Director for Lloyds TSB, explained: ‘To outsiders, it may seem strange to see a bank sponsoring motorcycle racing. The reality is that racing is at the heart of the Manx community. The TT is the most famous road race in the world, drawing in thousands of visitors and creating many spin-offs for local business.’ Lloyds TSB was a relative newcomer to racing, but Mannin Collections had been active sponsors since 1988.

Norman Kneen, one of the riders sponsored by Lloyds TSB and Mannin Collections, shows his sponsors’ names and colours to good effect as he rounds Governor’s Bridge.

Why so Named?

Duke’s

The series of bends at the 32nd Milestone are now called Duke’s after the legendary Geoff Duke, who particularly relished riding them. His TT heyday was in the 1950s, when he was even known by the man in the street for his exploits on the Island and at World Championship level. He then moved to live on the Island, developed many business interests there and was always prepared to help promote the TT if asked.

Almost fifty years after his TT successes over the Mountain Course, Geoff Duke was finally honoured for these and his many other efforts to publicize the Isle of Man’s name worldwide.

A great ambassador for the TT, Geoff Duke speaks at another function to promote the event.

TT Return

Two years is a very long time in racing: riders and teams change each season, as do their plans and the targets for their efforts. Rumours were rife on the approach to the 2002 TT about who would ride what, although the organizers were pleased to have an early indication that Honda and Yamaha would have ‘works’ entries. Indeed, Mark Davies, boss of Honda UK, said: ‘The TT is part of our heritage. As long as the event is here, we’ll be here too.’

One of the strongest rumours was that eleven-times TT winner Phillip McCallen was planning a return, perhaps on an RC45 bored to 1000cc. That rumour came to nothing, as did talk of Jim Moodie riding a Suzuki; instead he signed to ride for Yamaha via V&M Racing. It was V&M who featured in the really big pre-TT news when David Jefferies decided to switch from their Yamahas and join Ian Lougher in riding Suzukis for Temple Auto Salvage (TAS), which was receiving strong support from Suzuki. The previously dominant Yamaha R1 had set new design and performance standards, but Honda and Suzuki had not sat back, for with the R1’s race successes they had seen the sale of Yamaha’s road bikes soar at the expense of their own sales. Honda came to the 2002 TT with lightened and more powerful CBR900RR Fireblades for John McGuinness and Adrian Archibald, while Suzuki’s GSX-R1000 had also been much improved and was known to be a flier. As riders changed their allegiance (in Jefferies’s case less than three months before), a few toes were inevitably trodden upon, and tensions were created that added to the strong spirit of competition that accompanies every TT.

Many technical developments in the world of motorcycling are pushed along by the efforts of manufacturers seeking to steal a march on the opposition in the field of racing. The 180bhp ‘works’ Formula I bikes that came to the 2002 TT were capable of giving their output at up to 12,500rpm for much of the race. There had been moves towards fuel-injection, re-mappable ignition systems, slipper clutches, electronic gear-shift, quickly detachable wheels (to aid mid-race tyre changes), ever more refined suspension front and rear, much enlarged radiators and a general striving for lightness. The bike manufacturers’ efforts were supported by increasingly specialized tyres, as the tyre companies tried to build stability, consistency and durability into their products.

David Jefferies reminds spectators just how close they can get to the action as he uses almost all of the road on his TAS Suzuki at the Gooseneck in 2002.

The greater the scope for tuning and adjustment in almost every aspect of the bike, including ignition, suspension, brakes and tyres, the harder it became for riders to set the bikes up to optimum levels in the limited practice time available. They needed time on the course to do so and that was often in short supply, particularly if riders were running in several classes. The variations in Manx weather did not help with fine tuning, because changes in wind direction, wet and dry roads, and even temperature variations (particularly for two-strokes) could affect the settings required.

Welcome Back

Island businesses were pleased to see the races back and visitor levels matched those of earlier years. No one in the world of motorcycling had sought the cancellation of the 2001 TT, but there is no doubt that the break in the long tradition of racing over the Mountain Course brought home to many people just how important the TT Festival was to them. The organizers gave a substantial boost to the prize money for each race and then added a one-off, welcome-back bonus of £5,000 to each winner, which meant that a start-to-finish leader of the Formula I race would collect a huge £25,000, as would the winner of the Senior. With a newly created Joey Dunlop Trophy and £10,000 going to the man with the fastest combined times in the Formula I and Senior races, there was a lot of money for the fast men to ride for. Promising to be one of the best TTs ever, the rewards available at the 2002 event must have caught the attention of top riders and sponsors who did not normally contest the event, and the organizers hoped it would attract more of them to race on the Island in the future.

The cover of the TT programme for 2002 announced the return of the world’s greatest road race.

The racing of production-based machines was now a dominant aspect of the TT races. Pure racing machinery could only be found with 125 and 250cc machines and the number of 250 entries had been falling. Adjusting the race programme to suit, the Lightweight 250s lost their separate race status and ran at the same time as the Junior race. Perhaps as a response to that treatment the entry of 250s dropped from more than forty in 2000 to just twenty. The gap created in the programme was filled with a Production race for 600s run over three laps on Friday morning before the Senior. Another change saw the Singles race dropped and the Lightweight 400 race run with the Ultra-Lightweight 125s.

While racing in a TT normally served to bar a competitor from riding in the MGP, an exception to this rule was made in respect of the Production races, where they could ride without losing MGP eligibility. The 2002 TT already had entries from twenty-two former MGP winners, including 2000 Senior victor Ryan Farquhar, and they were joined by a string of aspirants to an MGP win who felt that a Proddie ride in the TT would help with their course-learning for the September races.

New for 2002 was the introduction of random breathalyser tests for riders. It was perhaps fortunate that they did not have breathalysers at the first TT, for after his win in 1907 Rem Fowler told how ‘twenty minutes before the start a friend of mine fetched me a glassful of neat brandy tempered with a little milk. This had the desired effect and I set off full of hope.’ There were also trials of machine-mounted transponders for timing purposes in several classes and, in a move aimed at improving safety, new types of ‘Air-fence’ barriers were in position at selected locations. As a tribute to Joey Dunlop, riding number 3 was not used in the solo races except in the Senior, where numbers were allocated on the basis of times and not by seeding. Aside from the professional racing, track days were introduced at Jurby airfield for those who wanted to emulate the stars, several of whom were expected to visit and give advice. Among race sponsors in 2002 were Duke, the Hilton Hotel and Casino, Scottish International, IOM Steam Packet and Standard Bank Offshore.

An Early Start

Mindful of the time they lost from the 2000 practice period due to bad weather, and the need for newcomers to be allowed adequate time on the course (plus the fact that everyone had been away for two years), the organizers brought forward the start of practice to an early session on Saturday morning. The weather greeted this move with strong rain and wind, causing a delayed start and convincing the star names to stay in bed. Although good weather allowed fast times on Monday evening, the weather was poor for much of practice week and in two of the poor-weather sessions the fastest sidecar clocked a better time than the fastest solo, albeit at 97mph. That was another first at the TT.

Bad weather usually involved more activity for the eight-man Travelling Marshal team mounted on their yellow and black Fireblades, supplied by courtesy of Honda and looked after by the local Honda agent, Tommy Leonard Motorcycles. Customary pre-practice and pre-race checks of conditions increase in poor weather and radio messages fly between the team and Race Control as the Clerk of the Course tries to get a course-wide view of road and weather conditions.

Why so Named?

Joey’s

Although it made no actual difference to the course as ridden, riders and spectators had to get used to a new name for the 26th Milestone, when it was renamed Joey’s in 2002.

In memory of a great rider and, fittingly, in recognition of his twenty-six TT victories, this nameboard carries no surname, but the whole of the motorcycle racing world knows that it acknowledges the achievements over the Mountain Course of William Joseph Dunlop, known to one and all as Joey.

Adrian Archibald was on a Honda 954 Fireblade in 2002, but could not match his earlier performances.

Man or Machine?

David Jefferies came to the 2002 TT having collected a hat-trick of wins in 2000 on a Yamaha and then proceeded to do the same thing again on the TAS Suzuki. In circumstances where a rider changes machines and continues to win races, there is a tendency to give most of the credit to the rider, but team-mate Ian Lougher backed Jefferies’ performances with a win, three second places and a fourth on similar Suzuki machinery (and a 125 win on a Honda), so perhaps this was an instance where the credit was shared by man and machine.

Jefferies’s wins came in the Formula I, Production 1000 and Senior races, and all were achieved in relatively comfortable and controlled fashion. In the Senior he dipped well below the eighteen-minute lap barrier, setting a fastest time of 17 minutes 47 seconds, a record speed of 127.29mph (204.85km/h). His rapid progress seemed to spur second place Ian Lougher (TAS Suzuki) and third place John McGuinness (Honda) to set their own fastest ever times in the Senior.

Yamaha achieved victory in the Junior with Jim Moodie and in the Lightweight 250 with New Zealander Bruce Anstey. As Bruce’s mother was Manx, his performance received plenty of coverage in the Isle of Man’s newspapers.

Bruce Anstey was a busy man at the 2002 TT, riding bikes from 125 to 1000cc and winning the Lightweight 250 race.

A performance that received even more local coverage was that of true Manxman Richard ‘Milky’ Quayle in winning the Lightweight 400 race. A popular and engaging racer who made his way up through the ranks of MGP winners, his words when interviewed on the top step of the rostrum were: ‘I never wanted to be a brain surgeon. All I wanted to do was win a TT’. After nearly nine years of racing and with more than his share of misfortune, ‘Milky’ achieved what many strive for but relatively few achieve. Leading from start to finish on his Honda, he won by twenty-two seconds.

The Blue Riband?

For more than fifty years the Senior TT was the most important race of the meeting. It was given the prime Friday spot on the race programme, and race week customarily moved towards its climax with the running of what was known as the Blue Riband. But the growth in importance of Formula I racing through the 1970s and 1980s, allied to the loss of specialist Grand Prix-type machines from the Senior, saw a reduction in its importance and it lost its prime position, being pushed about to suit the organizers’ convenience. Through the 1990s it recovered some of its prestige and its end of week position, but, with many riders wanting to get away to busy race programmes at the weekend, there was a tendency for some to leave early and miss the Senior, making the number of riders in the Friday race often less than that shown in the spectators’ programmes.

With the switch to Senior entry being determined by the fastest eighty qualifiers rather than by the normal pre-race method of entry, the situation regarding non-starters grew noticeably worse. It was understandable that at the end of a fortnight’s racing there would be riders missing through injury or major machine failure. In addition, however, now that fast MGP-type runners were allowed to compete in the Production TTs, it was inevitable that about a dozen of them appeared among the fastest eighty qualifiers for the 2002 Senior: but, of course, none turned up to race in the Senior because it would have ruled them out of the MGP. While the organizers tried to counter the loss by hastily extending invitations to a few of the less speedy qualifiers, it created a chaotic and embarrassing situation for commentators like Geoff Cannell who had to announce a long list of non-starters and alterations to entries. In 2002 only fifty-one started and, with twenty-one retiring, a field of thirty riders was not enough to hold spectators’ attention or command the title of Blue Riband, notwithstanding the record-breaking speeds achieved by the men at the head of the field. It was a problem needing a speedy solution, for quantity as well as quality is needed for a TT race to be successful in the eyes of those watching.

While most people knew that competing at the TT (Production classes excepted) made a rider ineligible to take part in the MGP, there was another twist to the ruling. For twenty years the MGP meeting had included hugely popular Classic races for the machines of yesteryear. The regulations for those Classic races did allow TT competitors to take part: Bob Heath did so with particular success in the 1980s and early 1990s, Phil Read and Nick Jefferies were slightly less successful. Even Joey Dunlop had a go on an Aermacchi. At the 2002 MGP, ‘Milky’ Quayle, winner of that year’s Lightweight 400 TT, contested the Senior Classic MGP and came home victorious on Andy Molnar’s Manx Norton. In doing so he achieved a unique ‘double’.

A Balancing Act

Putting aside the problems over entries in the previous year’s Senior race, in 2003 the TT meeting was in a reasonable state of balance. Its excellent prize money ensured that all the top road racers competed, along with good men from circuit racing who could adapt to the roads. Manufacturer support was particularly good for 2003 and promising young riders continued to enter. The problems associated with getting to and from the Island (involving the cost and choice of dates) and the availability of accommodation had not gone away. They remained as problems, but nothing is perfect! Overall the organizers had a successful meeting that justified the money invested in it, bringing the Isle of Man massive publicity for its name via satellite TV transmissions of race highlights, as well as the income the racing brought to the Island.

The festival aspect of the fortnight continued to grow with new events. The commercially run track days were augmented by Honda offering off-road experience on a fleet of twenty-five machines. Then the growing sport of Super Moto featured in a meeting at Jurby, while the established Moto Cross, Beach Cross, sprints, grass track and trials events continued to be run, along with an occasional hill climb. One-make clubs all had their special meets, a vintage rally had a week of events, while bungee-jumping and special ‘rides’ went on round-the-clock on Douglas Promenade, adding to the regular evening wheelie and burn-out sessions. Rather more organized were the appearance of bands and groups, although there were mixed receptions to the artists who were booked. Putting on a race meeting to suit all tastes created difficulties, but they paled into insignificance compared to the difficulty (impossibility?) of choosing groups that would suit everyone, for it was most certainly an area where one man’s meat was another’s poison.

No one could accuse the Island’s road safety authority of not trying to catch the attention of TT visitors!

Something that occurred every year and was not welcomed by the Manx authorities and public was the considerable increase in road accidents that occurred over the TT period. No one wanted to see visitors damaging themselves, particularly as their ‘accidents’ so often involved innocent members of the Manx public trying to go about their normal lives. Road safety was a message that the authorities tried to get across, but it was a difficult task to convey during a period of high-octane excitement for 12,000 motorcyclists riding roads that an hour before might have been a race track, and over which there was no overall speed limit.

Timekeeping

Since the very first TT the progress of riders in a race had been timed with hand-operated watches. The team of timekeepers occupied a position overlooking the start and finish line and, assisted by spotters whose job was to identify and warn them of riders approaching along the Glencrutchery Road, they recorded every rider at the start and finish of each lap of practising and racing. Times were noted on official timekeeping sheets and speeds were derived from substantial reference books in which figures for speed against time were all pre-calculated. The figures recorded were passed to time auditors who double-checked that all was correct.

Timekeeping boxes opposite the grandstand.

By a system that involved the use of slips of paper, clothes pegs, drainpipes and Scout messengers, the times were passed to the men who maintained the scoreboard opposite the grandstand. They then painted each rider’s lap times against their numbers, for spectators and pit attendants to see. In the early days of public address and broadcasting, times were also passed by telephone for onward broadcast.

After the experiments of 2002 involving the use of machine-mounted transponders, the organizers decided that for 2003 the use of transponders would be mandatory and would be used to determine the race results, although manual timekeeping was retained for the year – just in case! Timing points at Glen Helen, Ballaugh, Ramsey Hairpin, the Bungalow and Cronk ny Mona allowed for a major improvement in the information that was automatically (and immediately) fed back to computer screens in the timekeepers’ and commentary boxes, thus permitting the progress of a race to be more closely monitored and the information quickly made public via the commentaries from Radio TT. Whatever the new system did for the technicalities of timekeeping, there was no doubt that it created added excitement for spectators to receive up-to-the-moment time gaps between riders contesting the lead. There were many benefits from the new system. For example, in a six-lap race commentators could see from the early laps if an individual rider vying for the lead made or lost ground over rivals over different sections of the course, and this allowed them to make more informed comment about what was likely to happen in the closing stages of a race. For rider support crews the greater frequency of timing information also allowed for more accurate signals to be passed to their riders although, inevitably, the lesser lights got rather fewer radio mentions than the stars.

Entries

When entries closed for 2003 all classes were oversubscribed and 319 individual competitors (169 solo and 75 sidecar crews) were accepted to race. For some reason the TT had gained popularity with French competitors and there were ten solo and six sidecar outfits from France, plus entries from nineteen other countries.

Formerly classed as Lightweight 250s with their own race (even if latterly run alongside the Juniors), the 250s lost their separate race status in 2003. They were allowed to enter the Junior (600) race and there was an award for the best 250, but it was one more step towards the axing of this once so popular class.

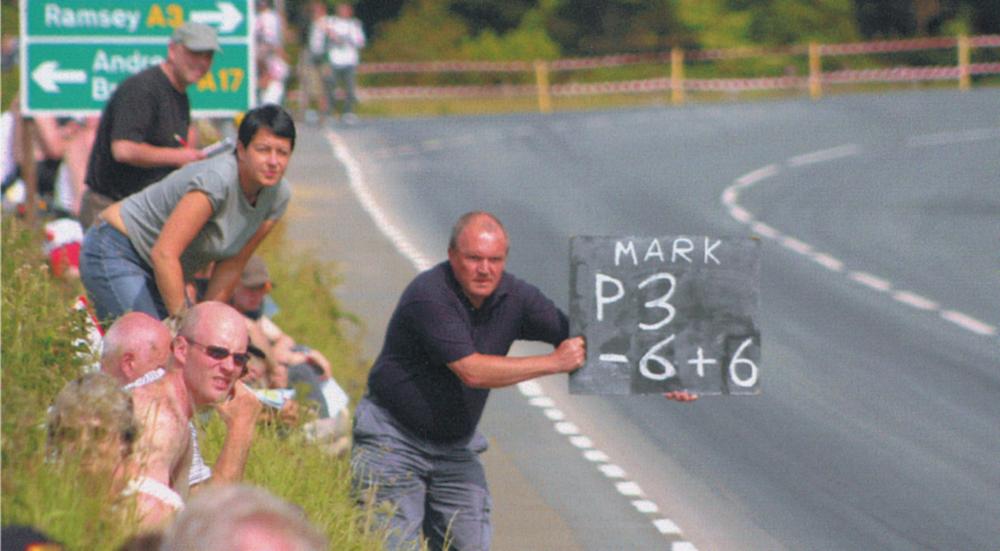

A member of Mark Parrett’s support crew holds out the signal board with his race position for Mark to read as he slows for Sulby Bridge.

To help pay for their racing efforts, French sidecar crew François and Sylvie LeBlond sold wine with a label that featured them leaping Ballaugh Bridge.

Sharing a paddock campsite wih the LeBlonds was the Voxan équipe, whose booming French-made V-twin offered spectators a welcome change in exhaust note from the dominant transverse fours.

Manufacturer Support

Mention was made earlier of how manufacturer support for the TT fluctuated down the years, but 2003 looked like being a good one with five concerns involved. Since its return to Island racing in 1977 Honda had been present every year and achieved considerable success, although in the last few years it had lost its number one spot to Yamaha and Suzuki in the all-important big classes. In 2003 it concentrated its TT effort on the second-fastest man around the Mountain Course, Ian Lougher, providing him with the 2002 World Super Bike-winning SP2 of Colin Edwards. There were considerable advances over the SP1 that Joey Dunlop rode in 2000, with revised fuel-injection, a slightly less rigid frame giving better traction and handling, plus the major engine changes introduced in the middle of the 2001 World Super Bike season. Not that the SP2 worked straight from the crate on the Island. No one really expected it to, but after tracing initial problems with stability at high speed to the tyres, Ian soon felt confident that he had a good set-up for the Formula I and Senior races on the 180bhp V-twin, which appeared in red and black Honda Britain livery.

Honda also provided limited support to Dave Molyneux with engines for his self-built DMR outfit. Dave came to the 2003 TT not having ridden since the previous October, for he had been too busy building outfits for his closest rivals.

Yamaha entered Jason Griffiths on an R1 built initially to British Superbike specification, but with slightly lower compression, 24-litre fuel tank, stronger fairing and strengthened bracketry to take the pounding it was to receive on the roads. The starter motor was retained to save precious seconds on getting away after pit stops.

Suzuki support went to David Jefferies and Adrian Archibald under the TAS banner. Although David was a favourite for TT wins in 2003, based upon past performances, he was slightly off the pace at the NW200 a couple of weeks before and admitted his concern that Adrian would press him hard. The GSX-R1000s were said to have about 8bhp more than in 2002 and came with an improved chassis.

Ducati representatives were John McGuinness and Michael Rutter, but pre-TT problems in British Superbike rounds saw Michael’s entry withdrawn by Team Renegade, losing him the chance of what might have been a couple of good pay-days. Apart from a Singles win at the TT on a BMW, victory in the big classes had eluded John McGuinness although, as third fastest lapper on the Island, he had six podium places to his name. Relatively inexperienced at riding the Ducati, John was nevertheless confident of doing well at the TT, saying of his 185bhp V-twin: ‘Compared to the Fireblade I rode last year [second in Formula I, third in Senior] the Ducati stops, turns and holds a line much better’. With three factory engines and a 999R for the Production race, John was entered under Paul Bird’s MonsterMob banner. The Ducati came with a reputation as being difficult to start, and the team had permission to use a portable roller starter after pit stops, but it was a process estimated to add 5 seconds to each restart.

John McGuinness takes a careful line through a glistening Ballacraine during an evening practice for the 2003 TT. The setting sun in his eyes also makes John cautious with his Triumph Daytona.

Nearly three decades after it last made a full ‘works’ effort at the TT, Triumph entered three of its 140bhp Daytona models in the Junior and Production 600 races, to be ridden by Jim Moodie, Bruce Anstey and John McGuinness.

The production heritage of all these machines was plain to see, but the days when lightly modifying production machines allowed manufacturers to go racing at far lower cost than with special GP models was now past. Wheels, forks, rear-suspension, brakes, tyre, radiators, fairings, exhausts and engine internals (where permitted) were all special racing components, meaning that the best bikes were now very expensive to build and maintain.

Black Thursday

David Jefferies was relatively slow in early practice before quickening his pace, while team-mate Adrian Archibald was fast from the outset. Was ‘DJ’ beatable? That question was on quite a few people’s lips, but it was one that was not to be answered. The long Thursday afternoon practice session is broadcast on Radio TT and the expectations of listeners were raised when the commentator described TAS Suzuki team-mates Archibald and Jefferies as streaking past the grandstand at 170mph almost nose to tail. Those watching at Quarter Bridge, Braddan Bridge and Union Mills thrilled to see the two aces pushing each other hard, while those further on at Greeba, Ballacraine and Glen Helen waited in anticipation.

But it was just Adrian Archibald who passed those spots – there was no David Jefferies. Had he encountered a mechanical problem and stopped? The sense of worry for spectators increased as the flow of passing riders slowed to a trickle and then ceased. Clearly there had been a major incident that brought riders to a halt. Although nobody wanted it to be so, most felt that it involved David Jefferies. Riders did eventually start to come past again, but no one could concentrate on what was happening on the course. Radio TT’s commentators were still broadcasting, but were telling spectators everything except the one fact they wanted to know – what had happened to ‘DJ’? The answer was that he had fallen with his machine at the ultra-fast left-hand kink in the centre of Crosby. Man and machine struck a wall and the finest TT rider of his generation was killed.

Other competitors, many of whom were close friends of the fallen rider, were halted by the incident and were witness to the aftermath. All were deeply shocked, as were the thousands of race followers who eventually came to hear what had happened. In a pre-race interview in Motor Cycle News, David Jefferies was quoted as saying, ‘At the TT I ride well within my limits. If you get it wrong you either hit a stone wall…’. These were the words of a man who knew the dangers and was prepared to take them on. With nine TT victories to his name, made up of three hat-tricks in 1999, 2000 and 2002, he was the outstanding talent from the three generations of the Jefferies family that had contested the TT and MGP from the early 1930s and been ever-present as competitors or on the organizational side through the efforts of grandfather Alan (second place in 1947 Clubman’s TT), father Tony (three times a TT winner) and uncle Nick (one TT win and many podium finishes).

Suzuki Victory

It was a chastened TAS Suzuki team that decided it would continue to race and so went about its preparations for the opening Formula I race. Boss Phillip Neill and his father Hector’s involvement with racing went back a long way (to include 1983 TT winner for Suzuki, Norman Brown). The team had experienced tragedy before and knew that it was inseparable from the racing game.

When the riders came to the line for Saturday’s Formula I race there must have been thoughts of David Jefferies in the minds of top runners such as Archibald, Lougher, McGuinness and Griffiths, all of whom had counted him as a friend. A delay of one hour in the start-time may have allowed some low-lying fog to clear, but it did nothing to help clear the minds of riders who were trying to get into the mood to race. Showing the remarkable resilience required of all front-line road racers who have to overcome personal tragedy, injury and machine troubles that would halt lesser men, Adrian Archibald (TAS Suzuki) rode to Formula I victory, finishing more than one minute ahead of Ian Lougher (Honda), John McGuinness (Ducati) and Jason Griffiths (Yamaha). It was Adrian’s first TT win, but one that was achieved in sad circumstances. It came as no surprise that he dedicated his victory to David Jefferies, and that the victor’s champagne stayed corked after the post-race garlanding ceremony.

Often late in putting his TT arrangements together from distant New Zealand, experienced runner Shaun Harris took his first TT victory when he rode a Suzuki home in the Production 1000 race, a feat he repeated for Suzuki in the Production 600 event that was curtailed due to poor weather on the Friday.

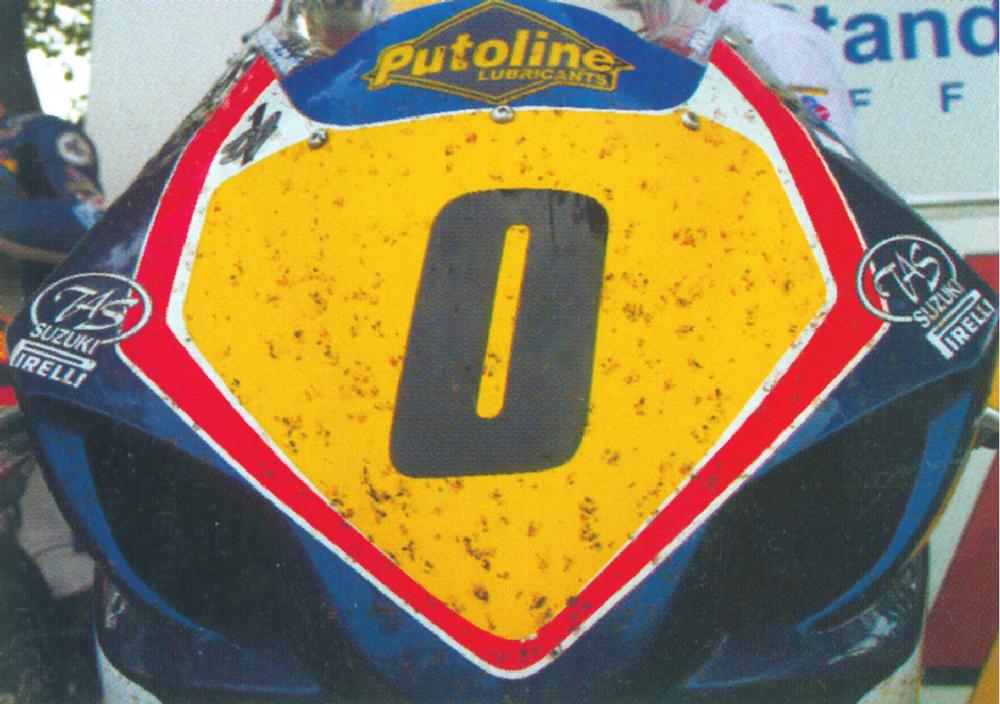

In a first at the TT, Adrian Archibald contested the Senior TT under number 0.

For the Senior, which was delayed until Saturday, then further delayed during the day and reduced to four laps, Adrian Archibald was allocated riding number 1. However, as numbers were allocated on the basis of times set in practice, and as he had not quite matched the late David Jefferies’s time, Adrian obtained approval to ride as number 0.

It was the top ‘works’ runners who headed the Senior field when the race eventually got under way: at the end of the first lap Archibald led by just 3.15 seconds from McGuinness, with Lougher close behind in third. Things remained close on the second lap when Archibald set the fastest lap of the race at 126.82mph (204.09km/h), even though it was one that involved slowing down to enter the pits for refuelling. He left 15 seconds ahead of McGuinness (might that have been 10 seconds if John had not needed to use the roller to restart his Ducati?) and built on his lead to win by 20.8 seconds from McGuinness, with Lougher third on his Honda and Griffiths fourth on the Yamaha. As usual, there was a prize of £1,500 for the best 750cc finisher in the Senior race, and it went to Mark Parrett (Kawasaki).

In what had been an emotional roller-coaster of a fortnight for all at the 2003 TT, Bruce Anstey produced the surprise of the week by racing a Triumph Daytona to victory in the Junior race, so giving British fans something to cheer. Patriotically finished with the Union flag on the nose of its fairing, the Triumph came home ten seconds in front of Ian Lougher (Honda), Adrian Archibald (Suzuki) and Ryan Farquhar (Kawasaki), so beating the best that Japan had to offer. Anstey’s bike must have been a real flier, for fellow Triumph runners Jim Moodie and John McGuinness (no mean runners) came home in ninth and tenth places.

In the Lap of Honour at the 2003 TT the letter ‘H’ stood for Hailwood, for Mike Hailwood’s son David did a lap on a Triumph Trident.

Richard ‘Milky’ Quayle rode this Suzuki with support from Padgetts, whose name has been associated with the TT for more than thirty years.

At a time when manufacturers acknowledged that race successes sold motorcycles, Honda had to be content with wins by Chris Palmer in the Lightweight 125 and Dave Molyneux in Sidecar Race B. It was not what they were used to at the Isle of Man races.

A Price to be Paid

In a very macabre outlook that Island racing induces, some riders believe that the TT course demands payment in tribute of riders’ lives each year, and when that happens they breathe more easily. The death of a star like David Jefferies was bound to make front-page news, but the death of Peter Jarmann at the 2003 TT attracted far less publicity. However, Peter was well known to real fans of the TT as one of the regular stalwarts who made up the numbers in the races, and so kept them interesting after all the stars had flashed past at the head of the field. He came from Switzerland to race in the TT each year (and often in the Southern 100 and Classic MGP events) and on the Monday of race week he rode to ninth place in the Lightweight 400 race. Such was his enthusiasm for all things connected with the TT that, a few hours later, he wheeled out a Classic Bultaco to ride in the Lap of Honour that took place after the Production 1000 race. Less than half a mile from the start the Bultaco seized; Peter was thrown against an unyielding wall on Bray Hill and was killed. Once again motorcycle racing and the Mountain Course had conspired to show its cruel side.

One man who managed to cheat death in 2003 was ‘Milky’ Quayle. Coming over the rise at Ballaspur on his big Suzuki, he touched his left shoulder against the rock-face. Man and machine were projected diagonally across the road to hit the opposite bank and he was sent cart-wheeling down the road. Seriously injured, ‘Milky’ decided that he had been one of the lucky ones and, putting his family first, he retired from racing. He remains committed to the sport that allowed him to achieve his life’s ambition and win a TT, and today he fulfils a role in promoting the event and attracting new riders.

Tragedy struck away from the TT later in 2003 when Steve Hislop, eleven-times winner on the island, was killed in a helicopter crash shortly after winning the British Superbike title.

Promotion

One of the many ways in which the TT is promoted is via the power of the press. Although it could sometimes, with justification, be critical of the event, Britain’s mass-circulation Motor Cycle News always gave the races good coverage. During the run-up to the 2004 event former editor Adam Duckworth explained how, ‘The TT is brilliant, frightening, fun, dangerous, anachronistic and, for that reason alone, a jewel that we must never lose sight of’, while current editor Marc Potter visited after an absence of seven years and felt things were better than ever. There was little doubt that the unique character of the event served as a magnet to attract people from all over the world, for all realized that nowhere else could they see such a ‘festival’ of motorcycling, dominated by racing over the famous Mountain Course. It was a high-speed fortnight for many visitors, but one event in 2004 that actually ran at controlled speed was an organized Lap of Honour in memory of David Jefferies by 3,500 bikers riding the 37¾ miles in front of thousands of spectators on Mad Sunday. It was an impressive tribute and many of those riding and watching sported ‘DJ’ tribute T-shirts, bought in aid of the David Jefferies Memorial Fund.

Organization

Since 1907 the TT meeting had been organized by the ACU. Every year its senior officials and selected voluntary helpers packed their bags for a fortnight away, made passage to the Isle of Man, checked in at the best hotels and enjoyed an all-expenses-paid holiday. Well, that was how it was seen by the countless number of Manx enthusiasts who also put in a fortnight’s effort (three weeks in the very early days) in support of the racing, with many also fitting in their normal day’s work.

While many genuine friendships formed between ACU and Manx helpers, there were also frequent tensions between the two tiers of organization. In the 1920s the ACU threatened to take the races away from the Isle of Man if it did not contribute towards the direct running costs of the event. The Island has always met the many indirect costs of the TT, such as course improvements, and eventually did start to make direct contributions, initially to meet the expenses of riders coming from overseas. This grew until it reached the present-day position where it meets almost the whole cost of the event. As its financial contribution increased, so the Island demanded a greater say in the running of the races.

A significant moment in TT history: Jim Parker of the ACU (seated left), David Cretney, representing the Isle of Man Government (seated right), David Mylchreest of the Manx Motor Cycle Club (standing left) and Ted Bartlett of the ACU (standing right) sign documentation that transferred the running of the TT to the Island.

By the new millennium the ACU had transferred almost complete control of the running of short-circuit meetings in the UK to promoters, leaving just the TT to be run from its Rugby headquarters and by the staff it moved to the Island for TT fortnight. Down the years there had always been low-key agitation for the Island to take over the running of the event, for the Manx Motor Cycle Club was experienced in running the Manx Grand Prix over the same Mountain Course and had a suitable organization in place. It was a change that could not be achieved without the agreement of the ACU, but after much discussion the major controlling body of UK motorcycle sport eventually granted a licence to the Isle of Man Government to run the TT for twenty years, and the Government appointed the Manx MCC to organize and run the event on its behalf from 2004.

No one knows exactly how many people are required to run the TT. The programme sold to spectators lists some 150 officials, ranging from the race management team, through the Clerk of the Course, scrutineering team, start/finishing line team (numbering seventeen people), Travelling Marshals, timekeepers and scoreboard staff, to the Press Officer, Incident Officers, Medical Officer, Welfare Officer and Chief Environmental Officer. They are the tip of the iceberg, for on race days the aim is to have 1,200 marshals dispersed around the course, plus doctors, paramedics, rescue helicopters, recovery vehicles and Civil Defence radio-communications staff, all on active duty; other support services, such as hospital staff, road-sweepers and highway workers, are on standby should they be needed. Every race has a scheduled 180-minute count-down to the start. Taking a round figure of 1,500 support personnel on duty it means that, before a race with an entry of seventy-five, an average of twenty people move into place to support each rider.

‘New’ Organization

The average spectator was little affected by the appointment of the Manx MCC as new organizers for the 2004 TT, although, in a couple of controversial moves, morning practice was abandoned and the Formula I and Senior races reduced to four laps distance. As with many changes at the TT it was surprisingly difficult to discover the real reason for them. In respect of dropping the long tradition of morning practice, there were mutterings about not being able to get enough marshals on the course so early in the day (marshals have been used as a scapegoat for a number of the TT’s ills), while from close to the organization came the guarded revelation that riders were not happy with modern-day tyres in the sometimes patchy damp conditions that could be found at an early hour. In reducing the meeting’s two premier events from six to four laps the organization justified its action by claiming statistics showed that more accidents happened towards the end of a long race. It was a change opposed by many riders and spectators.

Jason Griffiths came to the TT from the MGP and has achieved many podium places, latterly for Yamaha.

Racegoers noticed an ever-growing attitude of caution exercised by the organizers in respect of the conditions in which riders were allowed to race. This was shown in more frequent delays to the start of races, as they waited for roads to dry and mist to lift, while for 2004 they introduced an additional warning signal comprising a white flag with a red diagonal cross to indicate ‘lack of adhesion other than by oil’. Allied to the organizers’ caution came increased influence from the Health and Safety Executive on aspects such as refuelling and spectator locations around the course. The latter caused much concern, particularly to experienced fans who had watched from a particular spot for perhaps twenty years, only to be told that it was no longer safe to do so. The TT was changing and some riders and spectators did not like what was happening.

The Entries

With a total of 731 race entries, including thirty-seven foreign and fourteen female riders, the 2004 TT welcomed back ten former winners and many regular leader-board names who were still looking for a win, among them being Jason Griffiths, Ryan Farquhar, Richard Britton, Nigel Davies, Gordon Blackley, Steve Linsdell, Jun Maeda from Japan, and from the Isle of Man Gary Carswell and Paul Hunt on solos, plus sidecar duo Nick Crowe and Darren Hope. A surprise late entry among the sidecars was 2002 World Champion Klaus Klaffenbock, with Christian Parzer in the chair.

John McGuinness said all the right things about his R1 to please Yamaha’s public relations people, including ‘it’s the only bike I’ve ever hit jumps on nailed, and it lands dead straight’. Vic Bates was at the top of Crosby Hill to capture John and the Yamaha ‘nailed’ at over 160mph – but far from straight!

Honda had lost its previous dominance in the larger categories of the road-bike market as Suzuki, Yamaha and Ducati wooed the buying public with impressive performances at the TT and in World and British Superbike racing. In a move that probably would not have impressed Soichiro Honda, the response of the company’s British arm was again to provide support for just Ian Lougher, doing it via Mark Johns Motors. It claimed it was too busy to support the TT fully, although some watchers felt that it was an attempted snub to the meeting as changes it had asked for had not been implemented. Cynics contented themselves by pointing out that Honda had not done much winning on the Island of late. Kawasaki had a presence with Ryan Farquhar riding under the Winston McAdoo banner, and there were many who thought that Ryan was overdue a TT win.

Yamaha supported Jason Griffiths and John McGuinness and, showing that the Japanese manufacturers still rated the TT highly, UK Sales and Marketing Director Andy Smith said how Yamaha Japan first presented the R1 to him with the words ‘Think of it as an Isle of Man bike’. The R1 certainly proved itself as a TT winner, although a little more thought from Japan in the design stages as to its fuel consumption while racing in the Production classes might have seen it fitted with something larger than its standard 18-litre fuel tank. Riders knew that getting two laps from a tankful was touch and go, and the way the fuel warning light always blinked ominously on the descent of the Mountain on the second lap was a psychological barrier to keeping the throttle to the stop.

Having read about the TT in Argentina in their younger days, Walter Cordoba and David Paredes were now TT regulars and were themselves making headlines in the sports pages of their home newspapers. Back on the Island for another year of racing, neither expected to win a TT but both were close to achieving 110mph laps with their 600 Hondas in the Junior.

Judging that the experiment with the Senior TT of the past few years of inviting the fastest eighty qualifiers in practice to contest the Friday race was a failure, the organizers reverted to the traditional method of taking pre-race entries, and eighty-two were received.

During the 2004 Formula I race, the eventual winner John McGuinness (Yamaha, 3) has his main rival Adrian Archibald (TAS Suzuki, 1) he wants him. Having caught and passed Archibald on the road, McGuinness knows that he has a 20-second lead as the two of them heel through sweeping bends of the 11th Milestone at 140mph.

The Racing

Without a regular ride on the short circuits in early 2004, John McGuinness came to the TT supported by Yamaha with R1 machinery. In what was to prove a very successful visit, John had a secret weapon in his race team in the shape of non-riding Jim Moodie. Admitting to being ‘a bit laid-back, a bit lazy, a bit last minute’, John found the well-organized and vastly experienced TT-winning Scot to be just the person to do a bit of thinking, pushing and organizing for him. Perhaps Moodie lifted a little pressure from the rider and gave him confidence, and although the effect of rider confidence cannot be measured in lap times, for a family man like John who did not intend to push himself over the limit, a settled state of mind must have been a big plus. Indeed, many riders have said that a relaxed approach to riding the TT course yields faster laps than pushing hard. With a slowish start but an overall good practice week, John rode the Formula I race with plenty of confidence, racing to victory by eighteen seconds over Adrian Archibald (TAS Suzuki) and setting a new lap record on the first lap of 127.68mph (205.47km/h). Bruce Anstey (TAS Suzuki) was third and Jason Griffiths brought the other ‘works’ Yamaha into fourth, with Ian Lougher (Honda) fifth.

Switching to a private Honda for Monday’s Lightweight 400 race, the thirty-year-old McGuinness took a comfortable victory for the second year on the trot. The Ultra-Lightweight race for 125s was run as a separate race at the same time as the 400s, but everyone knew that, just as with the racing 250s allowed to run in the Junior, the year of 2004 was to be the final TT appearance for both of these pure racing machines. Once again the reasons put forward by the organizers did not quite ring true, as race fans looked at British and World Championships still catering for good fields in both of these capacities. Was it manufacturer interest and pressure seeking to clear the programme for other classes that caused the organizers to run down and then drop the 125s and 250s? Who knows – but it certainly had the effect of reducing the number of individual riders contesting the TT thereafter.

With the brakes of his Honda applied and front forks on full depression, Chris Palmer prepares to take Sulby Bridge on his way to victory in the 2004 Ultra-Lightweight race.

Chris Palmer won Monday’s Ultra-Lightweight race, setting the fastest lap at 110.52mph (177.86km/h) in a field comprised entirely of Hondas. Second place went to five-times TT winner Robert Dunlop, who announced that the axing of the 125 class meant that it was his last TT. Joint sponsors of three riders in the race, Lloyds-TSB and Mannin Collections were another concern unhappy with the organizers’ decision to drop the 125s. They had plenty of opportunity to race the 125s elsewhere but, as Manx organizations, they did wonder why they could not do so at the TT. Monday’s second race, the Production 1000, was unusual as it was stopped at Sulby Bridge on the first lap as sea mist crept in to affect the relatively low-lying Cronk y Voddy area. Rerun on Tuesday, Bruce Anstey seized the chance to break the McGuinness grip on the 2004 races and bring his Suzuki home ahead of John’s Yamaha by eighteen seconds for his third TT win.

Riders are red-flagged at Sulby Bridge on the first lap of the Production 1000 race after visibility problems affected part of the course.

Dave Molyneux and Daniel Sayle made up undoubtedly the top sidecar crew at the 2004 TT.

In a double Manx-double, local sidecar crews Dave Molyneux/Daniel Sayle and Nick Crowe/Darren Hope took first and second places in both Sidecar races with their DMR Honda outfits, ‘Moly’ lapping at over 113mph and equalling Rob Fisher’s total of ten TT wins. Former World Champion Klaus Klaffenbock made a steady debut, building up to a 104mph lap, and promised to return to race again.

In 2004 Nick Crowe and Darren Hope were on a rapid rise to TT stardom.

With track conditions less than ideal due to oil spillages in several places, John McGuinness exercised a degree of caution in the Junior race and still came up with a win for Yamaha on his R6, ahead of Bruce Anstey’s Suzuki. The usually steady Ian Lougher was lucky to get away unharmed from a first-lap crash on his Honda on the approach to Union Mills.

With just Friday’s two races, the Production 600 and Senior, left to run, fans wondered if John McGuinness, the star of the meeting to date, could achieve a new TT milestone and win them both, so lifting his victories for the week to a record-breaking five. As ever there were other riders with eyes on the top places in those races and it was Ryan Farquhar who broke his TT duck by winning the Production 600, so giving a rare victory to Kawasaki and its ZX6. In a close and exciting race, Ryan had just 2.3 seconds in hand over runner-up Bruce Anstey (Suzuki) at the finish. John McGuinness was in contention for the lead until a steering damper bolt snapped on the third lap, causing him to ease the throttle as his R6 became a bit wayward on the bumpy stretches. Showing his form in the afternoon’s Senior, McGuinness led the race until the third lap when clutch failure forced him out at Glen Helen. With Yamaha’s other rider Jason Griffiths out on the first lap, plus Ryan Farquhar and Shaun Harris as other early retirements, Adrian Archibald (Suzuki) moved into the lead and held it to the end of the four-lap race. To McGuinness went the fastest lap at 127.19mph (204.69km/h), Bruce Anstey (Suzuki) earned another second spot and Manxman Gary Carswell (Suzuki) took advantage of the retirement of several top runners to snatch third from another local, Paul Hunt, after he dropped out on the last lap. It was Archibald’s second Senior TT win on the trot and with it went the Joey Dunlop Trophy and £10,000 for the best combined finish in the Formula I and Senior. Coming from Joey’s home town of Ballymoney, the trophy meant much to Adrian, as did the almost £20,000 he earned from Senior victory.

Among those to catch the eye at the 2004 TT was Martin Finnegan for his sometimes hectic riding style and his increase in speed over the previous year, plus newcomer Guy Martin, whose first ever lap of the Mountain Course was completed at 112mph and who finished the fortnight with a lap of over 122mph and seventh place in the Senior race.

Major Changes for 2005

It was customary for the programme for the next TT to be announced either at or soon after the current year’s event and TT followers soon heard that, for 2005, gone were two-strokes, gone were the names Formula I, Lightweight and Production, and in came Superbike, Superstock and Supersport racing, leaving only the Senior and Sidecar A and B titles remaining from the 2004 event. The organizers explained that the programme had been changed to suit the views of riders and teams, and that ‘the key features of the new programme are a reduction in the number of classes and a harmonization of those classes with what happens elsewhere in motorcycle racing’.

The TT had allowed itself to become slightly out of step with the categories of machines raced on the UK short circuits, causing extra expense to riders who had to modify their bikes to meet the TT regulations, so harmonization of specifications made sense. Reducing the number of classes also meant fewer individual machines to prepare, but the result was that there were just three solo classes in 2005. TT Superbike replaced Formula I as the major class, with machines complying with World Super Bike or British Superbike specification. Production racing was replaced by TT Superstock for machines of over 600cc meeting the specifications of FIM Superstock and MCRCB Stocksport. The third class was for Supersport Junior TT bikes complying with FIM Supersport or MCRCB Supersport rules. All three of the new categories were eligible to contest the Senior TT.

The reversion to an all four-stroke TT mirrored the situation at the first TT races of 1907, although 100 years ago this was by accident rather than by design. Similarly the wholesale use of production-based machines in 2005 was another echo from 1907. But in seeking to justify the exclusion of pure racing bikes (125 and 250 two-strokes), partly on the grounds of cost, everyone conveniently overlooked the fact that the Superbikes prepared for 2005 were out-and-out racers sharing few components with their production origins, and prepared on a no-expense-spared basis by the factories to win on the world stage and sell their road-going products.

The outcome was a programme of just seven races with the Supersport Junior TT runners given two races classed, like the sidecars, as Race A on Monday afternoon and Race B on Wednesday morning. Other changes for 2005 saw the opening Saturday Superbike and closing Friday Senior TT revert to six laps, while the option for MGP competitors to compete in Superstock (formerly Production) without ruling themselves out of competing in the ‘amateur’ races was withdrawn. The result was an entry of just 244 individual competitors, although it was pleasing to see Honda, Suzuki, Yamaha and Kawasaki giving ‘works’ support.

An innovation was that the first practice lap by those falling into the Newcomers category was made under the control of Travelling Marshals riding at the head, middle and tail of the orange-jacketed group of first-timers. Due to the extremely windy conditions of the opening session, the organizers sought to take pressure off riders, and discourage them from taking risks, by telling them that no times would be recorded. John McGuinness (Yamaha) was the fastest man at the end of practice week, with Adrian Archibald (Suzuki), Richard Britton (Honda) and Martin Finnegan (Honda) also showing well, while Ian Lougher (Honda) and Bruce Anstey (Suzuki) were a little slower. Time was lost with severalwet practice sessions, and previous caution by the organizers manifested itself into a statement from the Clerk of the Course, Neil Hanson, that the organizers would no longer start a race in wet conditions, though he did explain that: ‘If it rains during a race riders must make the best of it … but if I felt conditions were dangerous I would stop the race’. It was the increased power outputs of modern superbikes and the increased specialization of racing tyres (solo and sidecar) that brought about this move in the interests of safety, but it was one that suggested riders and spectators could look forward to even more delayed starts and postponements as the fickle Manx weather exercised its options to interfere with racing in years to come.

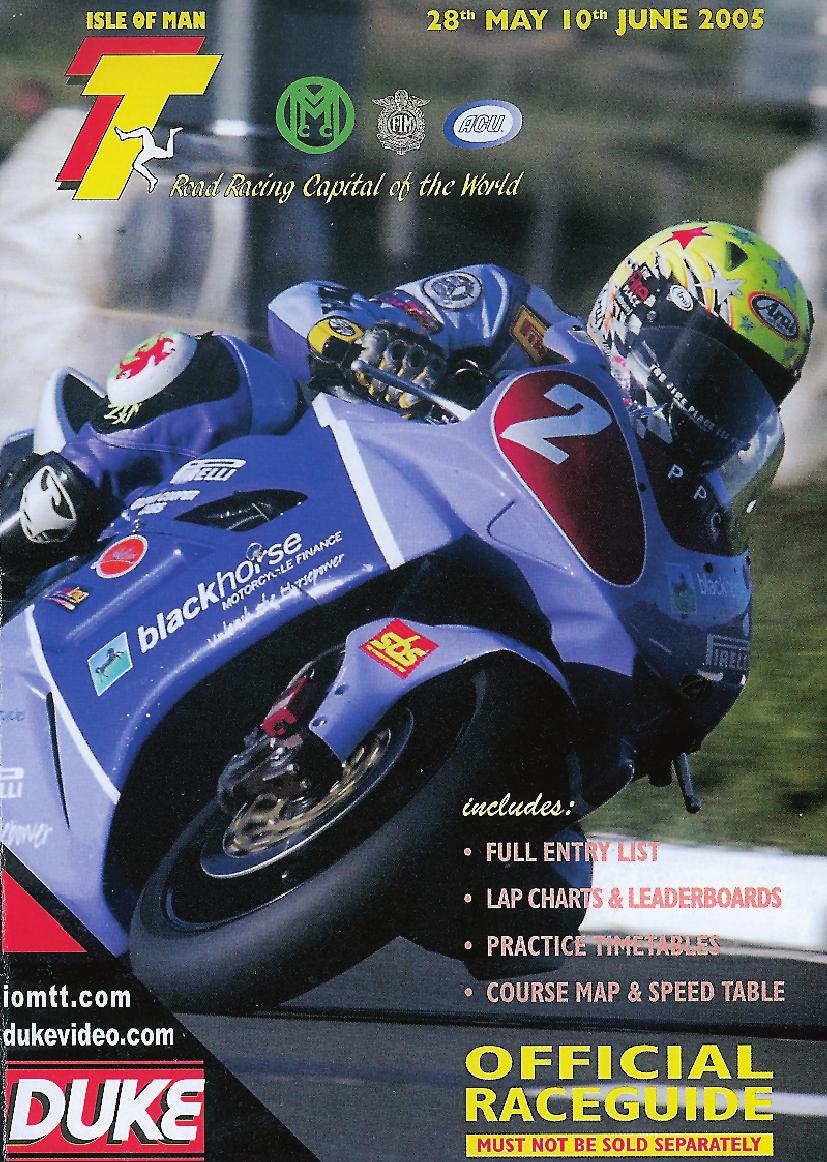

The cover of the Official Race Guide for 2005. The Isle of Man has long called itself the ‘Road Racing Capital of the World’.

With extra effort being put into the ‘Festival’ aspect of the TT, there would certainly be things for fans to do if racing was to be postponed, and official word was that ‘2005 will see the greatest collection of entertainments and shows ever seen at a TT Festival’. New events included TT chat shows with star riders as part of the evening entertainments, and paddock walkabouts on race days. There were also plans for a grandstand to be erected on Douglas Promenade for spectators to view organized stunt-riding displays and other entertainments.

Although much improved, the TT paddock drew complaints from riders every year, sometimes arising from unrealistic expectations, and the organizers promised more tarmac and a better layout for 2005. There were also going to be several small screens where transponder timing information on riders would be displayed during a race in the paddock/grandstand area. The same area provided a base for such concerns as K-Tech Suspension and Arai helmets to provide a service to riders using their products, while other commercial outlets sold race-style clothing, helmets and so on to the general public.

2005 Racing

The first postponement came on the opening day of 2005 race week. Wet roads and poor visibility meant the races were transferred to Sunday, when road conditions were good for the inaugural Superbike event. John McGuinness used the policy that yielded success in 2004 and went hard from the start, revving his Yamaha to 13,500 and leaving the competition to play catch-up. That was something that they could not do and, after early challenger Richard Britton retired, John was able to limit his revs to 12,000 in the closing stages and come home thirty-six seconds ahead of Adrian Archibald after 226 racing miles, leaving rising star Martin Finnegan to take third place. It was former Moto-crosser Finnegan who featured in lurid press photos showing him grinding the belly-pan as his Honda went on to maximum suspension depression at the bottom of Barregarroo, and of him leaping high and long at Ballaugh.

Top sidecar man Dave Molyneux had Daniel Sayle in the chair again, but the pair were sidelined by an ignition fault in Sidecar Race A and victory went to Nick Crowe and Darren Hope (Honda). In Race B Molyneux and Sayle smashed lap and race records when taking their Honda to victory over Crowe and Hope. Recording the first official sub-20-minute sidecar lap, the winners left the record at a staggering 116.04mph (186.74km/h). A scare in the last half-mile of the race when a wheel-bearing started to fail was accompanied by post-race revelations of one or two other faults not previously experienced, suggesting that venturing into the uncharted territory of 116mph on three wheels was going to call for a rethink on design.

Monday’s racing started with TT Superstock (formerly Production) over three laps, which was open to 4-cylinder machines over 600 and up to 1000cc, 3-cylinder machines over 750cc and up to 1000cc, plus twin-cylinder models over 850cc and up to 1200cc. It was monopolized by the Japanese manufacturers, with just an Aprilia of Mike Hose and MV Agusta of Thomas Montano to give a touch of variation and provide a change in exhaust notes. After leading the race until the closing stages, Adrian Archibald ran out of petrol on his TAS Suzuki, leaving team-mate Bruce Anstey to take the win from Ian Lougher (Honda), Ryan Farquhar (Kawasaki) and Jason Griffiths (Yamaha). To Archibald went the fastest lap at 126.64mph (203.80 km/h). Suffering two inexplicable high-speed slides early in the race, a de-tuned John McGuinness retired his Yamaha. But McGuinness could not afford to stay de-tuned for long because less than two hours after pulling in he was due to ride in the Supersport Junior TT Race A, where 4-cylinder machines over 400 and up to 600cc, plus twin-cylinder over 600 and up to 750cc were permitted. After a close struggle against the clock in which they were separated by less than one second (although fifty seconds apart on the road), Ryan Farquhar retired his over-heating Kawasaki, leaving Ian Lougher to take the win at an average speed of 120.93mph (194.61km/h), from back-on-the-pace John McGuinness (Yamaha).

The TT is always a busy time for mechanics and helpers.

Ryan Farquhar made up for his Race A disappointment when he rode to victory in Wednesday’s Race B of the Supersport Junior TT. What looked like being a closely contested race, as Farquhar, McGuinness and Lougher all contested the lead in the early stages, turned into a comfortable win for Ryan, with Jason Griffiths (Yamaha) second and Raymond Porter (Yamaha) third, following the retirement of McGuinness and Lougher. The retirement rate was higher than expected in Race B, in which there were fifty-eight finishers compared with seventy in Race A, and it was widely felt that the increasingly super-tuned nature of the 600cc Supersport fours was such that they could not be guaranteed to last for practice and two races. Notwithstanding the excellent mobile workshop facilities (and temporary garages) enjoyed by the top teams, an engine rebuild now entailed the use of more specialized facilities, something that was not possible between races. Perhaps even after nearly a century of racing the demands of the Mountain Course had once again been underestimated. Rumbles of discontent on the issue suggested that it might be an area for change.

Unreliability was also evident in Friday’s Senior TT, in which there were thirty non-finishers from seventy-nine starters and rostrum places were affected. There seemed little doubt that John McGuinness was heading for a win as he made his usual fast start and set the fastest lap of the race on his opener at 127.33mph (204.91km/h), and it was a position he held to the finish. Adrian Archibald held second until forced out with a puncture, while team-mate Bruce Anstey wisely retired when his Suzuki ‘did not feel right’. Potential rostrums were lost by Richard Britton and Martin Finnegan with slow pit stops, and Ryan Farquhar lost third place with a broken engine. Although Ian Lougher gladly took advantage of the situation to finish in second place, he was troubled with tyres that went off after just one lap. Renewing them at each refuelling stop (at the end of laps two and four) restored the grip, but it did not last. Taking third step on the rostrum was Guy Martin (Yamaha), in only his second year at the TT, who beat Martin Finnegan by just over one second to snatch the honour.

Two riders who finished the 2005 event with their highest-ever TT positions were Jun Maeda (11) and Guy Martin (15). Here they heel over at 140mph to pass the 11th Milestone, with Guy 30 seconds ahead on corrected time.

As there was only one race on Friday in 2005, a little more ceremony was attached to the Lap of Honour for Classic race bikes and riders. Former TT riders were sent off in the first grouping of about eighty riders, followed by a second group of fifty riders on Classic racing machinery controlled at the front by Travelling Marshals. The organized presence of Classic machinery was also extended to cover the weekend after the Senior, during which they were displayed in several locations and did laps of honour at the post-TT race meeting on the Southern 100 circuit.

Comparisons

Manufacturers, riders and sponsors had seemingly achieved what they wanted in 2005: a TT meeting spread over just seven races comprising three solo classes and sidecars, two groups from which (Sidecars and Supersport Junior) each had two races. But what of the TT’s 40,000 spectators – was there enough variety to keep them coming?

As the MGP approached, two months after the TT, a Manx newspaper chose to make the sort of comparisons that must have gone through the minds of many fans of Island racing, describing the TT races of production-based bikes as: ‘little more than three 1000cc and two 600cc solo events of similar design and outward appearances to the over-the-counter machines ridden on the open roads by the majority of road riders worldwide’. Although omitting mention of the Sidecar TT, it went on to point out that the MGP hosted some 400 individual competitors. It then indicated the variety of the MGP programme, with separate races for Newcomers on modern machinery in three different classes, races for modern machines in Lightweight and Ultra-Lightweights (open to the two-strokes dropped by the TT), plus Junior and Senior races for 600 and 1000cc machines in which riders were clocking laps above 120mph. In addition there were events for Lightweight, Junior and Senior Classic machines (using Classic capacity ratings), offering considerable variation of machinery by sight and sound.

Take your pick! TAS Suzuki was entered in all solo classes.

Strangely, the newspaper posed the question as to whether the increased specialization at the TT might be a good thing, wondering if narrowing the spectator appeal in June might prevent their numbers growing and, with the easier availability of boat crossings and accommodation during the MGP period, perhaps encourage some TT fans to visit the MGP instead.

While there are some who have swapped attendance from the TT to the MGP (for a host of reasons), it was difficult to believe that with the amount of money that the Island pumps into the TT it would want to see any decrease in numbers attending the premier event. However, it was still early days with the new arrangements of organizers and race classes, and there was bound to be speculation as to where the TT was heading.

What Races?

By the early months of 2006 there had been no announcement of the programme of races for the coming TT. Rumours flew in the press and on websites as to why there should be such an unprecedented delay. When the programme was eventually announced it was accompanied by much ‘PR speak’ about the lengthy discussions that had been held with all interested parties, but by then most people knew that one of the problems that had delayed matters was internal disagreement between those who paid for the races and those who organized them. The few who still believed that the delay was due to extensive consultation were no doubt surprised to see that all the talk had yielded little more than the fully expected omission of the second Supersport Junior Race and a hint of something extra for 2007.

The manufacturers had clearly got their way again about the dropping of the second 600 race, but that left the 2006 TT meeting with just six races. While it was natural to want to retain the support of the manufacturers and the associated status it conferred on the event, perhaps the TT organizers had got into the habit of leaning too far one way and not giving sufficient thought to spectators. From the earliest days through to the late 1960s the TT barely needed to worry about its status, for it was indisputably fixed at the top of the racing tree. When its position was threatened in the early 1970s, worries about maintaining status were paramount to the organizers. But, as was shown when it lost its World Championship ‘GP’ standing (followed by the loss of its World Championship Formula I title), the TT could stand alone. The same scenario prevailed with regard to protecting its dates against challenges from World and British Championship rounds, something the organizers became obsessed with. Yet during the opening weekend of the 2005 TT meeting there was a British Superbike round held at Croft, and over the middle weekend there was a Moto GP meeting at Mugello, with barely a mention of them affecting the TT.

Having laid those bogies from the past, it now seems to be the manufacturers who have captured the organizers’ minds. Many are aware that commercial forces want the TT condensed into a much shorter period than the current two weeks. Will they get their way? On current form, yes. But it is to be hoped that the organizers will listen to more than just the manufacturers’ views, for whatever their current demands, it should be remembered that they also need the TT as a showcase for their products.

Entries

Much of the considerable effort that goes into attracting new riders to race on the Isle of Man now falls to former winner ‘Milky’ Quayle and to Paul Phillips. Established riders receive personal approaches, offers of financial terms, and encouragement to come and look at the course, while up-and-coming riders are often brought to the Island in groups during the off-season and shown what the TT has to offer. Some of the funding for such group visits is paid for by the Mike Hailwood Foundation.

Wade Boyd tips into the right-hander of Quarter Bridge in 2002. The extrovert Wade has also ridden in Motocross and served as a sidecar passenger while on the Island. With his hair dyed in various colours, he has brightened the TT scene for many years.

An American newcomer to the TT, Jeremy Toye, is shown here on the Suzuki that he rode for regular TT sponsor Martin Bullock.