It was two thirty in the morning, and raining. In the City, it was always two thirty in the morning and raining … But I was still strapped into my life, bound by a plot I could no longer predict, condemned to ride the streetcar until the last stop.

– Kim Newman (1989: 3 & 37)

Like all good monsters, film noir escaped.

Often reduced to little more than an image or an idea – the city at night, the femme fatale – it is a touchstone of popular culture. From the 1985 Moonlighting episode, ‘The Dream Sequence Always Rings Twice’ and the 1986 Dick Spanner, P.I. animations to the 2003 computer game Max Payne 2: The Fall of Max Payne, allusions to this familiar megatext are readily perceived and understood. It is little wonder, then, that when the alien Strangers of Dark City construct an environment in which to perform their experiments upon abducted humans they choose to build and rebuild the eponymous locale.

Mike Wayne argues that German expressionism and American film noir lack lucidity because of an ‘existential crisis’ derived from the subject’s ‘incomprehension’ in the face of the ‘absurd and impenetrable world’ (2003: 216) of commodity fetishism and reification. In contrast, he suggests that Dark City is ‘hyperconscious of the politics of its intertextual cultural references’; but he nonetheless notes in it ‘that sense – difficult to pin down empirically – that the aesthetics have become, like the subjects in the film, a shell or bodily form emptied of the emotional power and substantive historical content/context that originally motivated them’ (2003: 216–7). As the world Wayne describes has become no less absurd or impenetrable since the middle of the twentieth century, it is not unreasonable to conclude that contemporary noir aesthetics and allusions now perform, among other things, a consolation. They offer an image of the world that, however distorted, is familiar and comprehensible. This consolatory tendency can be best explained in terms of the double logic of remediation, by which ‘our culture wants to both multiply its media and to erase all traces of mediation’ (Bolter and Grusin 1999: 5), and by briefly considering two neo-noirs from either end of the budgetary spectrum of contemporary digital filmmaking: This Is Not a Love Song and Sin City.

Although screened at festivals as early as January 2002, This Is Not a Love Song officially premiered on 5 September 2003, when it was simultaneously released in UK cinemas and on-line (the website received over a hundred thousand hits during its opening weekend). Shot for less than £300,000 in just twelve days, using a handheld Sony PD150 camera and DV tape, it refashions the couple-on-the-run plot in Deliverance (1972) territory. Taciturn ex-soldier Heaton (Kenny Glenaan) collects his excitable young friend Spike (Michael Colgan), just released from a four-month prison sentence for stealing £57, and takes him on a road trip in a stolen car. When they run out of petrol in the middle of nowhere, a farmer, mistaking Heaton for a thief, locks him up at gunpoint. Spike gets hold of the shotgun, but accidentally shoots and kills the farmer’s daughter, Gerry (Keri Arnold). Outraged locals divert the police search to London and then hunt Heaton and Spike across desolate moorland. As Heaton fails to get Spike to safety and, injured, has to rely on him more and more, so their relationship becomes increasingly fraught. With their pursuers closing in, Heaton begs Spike to carry him. They tussle. Spike hits Heaton on the head with a rock, leaving him for dead. Spike is taken by the locals, gagged, bound and drowned. The locals trace Heaton to a narrow cave and seal him up inside. Somehow, he survives and escapes but, like Vertigo’s Scottie, he is left confronting an emotional and psychological abyss.

Sin City was shot on high-definition video in front of a green screen, with many of the actors not actually meeting each other despite sharing scenes. Costing $40 million, it took $120 million worldwide in the first four months of its cinematic release. The portmanteau film is based on four of Frank Miller’s 1990s ‘Sin City’ comics – ‘The Customer is Always Right’, ‘That Yellow Bastard’, ‘The Hard Goodbye’ and ‘The Big Fat Kill’ – which delight in belonging to the crude pulp tradition of Mickey Spillane and garish paperback covers: Sin City is the kind of place where all the women are whores and all the whores are beautiful, capable of handling a gun and taking a punch.

In the opening vignette, The Man (Josh Hartnett) tells a beautiful woman that he loves her, then assassinates her. In the next story, Hartigan (Bruce Willis), an about-to-retire honest cop crippled by angina, rescues 11-year-old Nancy (Makenzie Vega) from paedophilic serial killer Roark Jr (Nick Stahl), the son of Senator Roark (Powers Boothe). In the next story, set eight years later, the seemingly indestructible Marv (Mickey Rourke) is framed for the murder of a prostitute, Goldie (Jaime King). Because she was nice to him, he sets out to find her killer, eventually teaming up with Goldie’s identical twin sister and fellow prostitute, Wendy (Jaime King). The trail leads him via other murdered prostitutes and Kevin (Elijah Wood), their cannibal killer, to Cardinal Roark (Rutger Hauer). Marv mutilates and murders the Cardinal, and is executed. In the next story, Dwight (Clive Owen) finds himself caught up in a mob scheme to regain control of Old Town, which is run by the prostitutes who work there. When Gail (Rosario Dawson), their leader and Dwight’s ex-lover, is abducted, he must set a trap in which they can brutally slay the mobsters. The film then returns to Hartigan. Senator Roark paid to keep him alive so as to force him to confess to Roark Jr’s crimes. Hartigan refused, but was convicted anyway as no-one would allow Nancy to testify. She promised to write to him in prison. Eight years later, Hartigan receives a severed finger rather than his weekly letter. Convinced Nancy (Jessica Alba) is in danger again, he confesses and is immediately released. He tracks her down-– she is a stripper and, she declares, in love with him – but it has all been a set-up to lead Yellow Bastard (Nick Stahl) to her. Hartigan again rescues her – Yellow Bastard is Roark Jr, horribly transformed by the chemical processes involved in replacing the genitals Hartigan shot off eight years earlier. Hartigan beats him to death and tears off his new genitals. Fearing that Nancy will be caught up in Senator Roark’s revenge, Hartigan shoots himself in the head. In the closing vignette, The Man offers Becky (Alexis Bledel), the prostitute who betrayed Old Town to the mob, a cigarette.

Despite their very obvious differences, these two films indicate the problem Wayne notes of the relationship between an aesthetics and its socially, culturally and historically specific contexts while pursuing the double and contradictory logics of remediation. Jay Bolter and Richard Grusin argue that ‘although each medium promises to reform its predecessors by offering a more immediate or authentic experience, the promise of reform inevitably leads us to become aware of the new medium as a medium’ (1999: 19). This contradiction is evident in This Is Not a Love Song’s intertwining of realist and expressionist techniques. At times shot with almost Dogme-like purity, the hand-held camera prowls around the action, often getting that little bit too close to the characters, sometimes losing focus, other times refocusing abruptly. Elsewhere, the film expressionistically distorts the image: blurs of colour replace the landscape through which the stolen car races; slow-motion disrupts the relationship between the image and diegetic sound; sat in front of a café window, Heaton and Spike are reduced to little more than silhouettes; when the panicked Spike brandishes the shotgun, he is filmed with a camera mounted on it; when Spike inhales an aerosol, he trips in day-glo colour. However, even as both sets of techniques claim a form of unmediated immediacy, they also draw attention to the medium mediating. While the handheld ‘realist’ camera places the viewer in the midst of the action, its shakiness, shifts of focus, zooms out and natural lighting are not merely aesthetic choices evocative of certain varieties of realism but also reminders that the camera being used is not so different from home video technology. Furthermore, in its positioning – whether in close proximity to the characters or, for example, half underwater as they hide in a river gorge – it becomes an expressive realism, emphasising a noirish entrapment. Meanwhile, the more obviously mediated and expressionist images – the blurred landscapes, the day-glo tripping – also suggest a direct and unmediated corporeal experience of speed or drugs.

This contradiction is mirrored in the relationship between Heaton and Spike. The insistence of PIL’s plaintive ‘This Is Not a Love Song’, which recurs throughout, unleashes the homoeroticism of both this particular story and film noir more generally. But the film simultaneously draws attention to the mechanisms of denial and suppression that fuel both it and the genre. Gerry is the only woman in the film. Fifteen years old, she is an unlikely potential third point to a noir love triangle; but even with the early removal of any threat she might pose to the men’s relationship, their feelings for each other can never be articulated. They talk incessantly, but say very little. Early on, Heaton denies having missed Spike while he was in prison, but then their exchange of glances as they argue over the radio becomes flirtatious, and their subsequent wrestling verges on becoming something else. When they spot the city that might offer them sanctuary, Heaton gazes lovingly at Spike as he gleefully dances. At night, they sleep curled around one another, untroubled by this physical intimacy. Both live in fear of being abandoned by the other. Most poignant of all is Heaton’s voice-over as, at various moments, we hear the opening lines of the many letters he tried to write to the imprisoned Spike but could never complete. The ambiguities of this relationship are never pinned down or named. The film instead gives us a sense of these characters’ immediacy to each other, while the mechanisms of shot construction and voice-over mediate that experience for the viewer, making their relationship at once both simple and complex.

Sin City is more noteworthy for its attempt to recreate the distinctive visual style than the narratives of its sources. Miller has spoken of the influence of comic artists Johnny Craig and Wallace Wood and, especially, Will Eisner’s ‘The Spirit’ comic strip (1940–52), although stylistically he seems most indebted to Kazuo Koike and Goseki Kojima’s violent 1970s manga Kozure Okami (Lone Wolf and Cub). The ‘Sin City’ comics are drawn in stark black-and-white, often with the simplicity of woodcuts. Long sequences are presented with little written text – for example, the 26-page ‘Silent Night’ contains one sound effect and a single speech bubble – while other pages are overburdened with words, with panels cramped by packed speech bubbles and long columns of text running down a thick margin. As Miller remediates the hardboiled novel in comic book form, the visual image claims a greater immediacy even as the intermittent excesses of text point to the inadequacies of the visual image at capturing aspects of the hardboiled novel. Similarly, the Sin City film uses digital tools to give its viewer the immediacy of the comic book image. However, there is again a contradiction. As the digital film remediates the comic book, the immediacy on offer is the product of hypermediation. By ‘recreating’ Miller’s simple illustrations – some of which are displayed in the title sequence – the medium draws attention to, rather than effaces, itself.

In addition to the image, the film remediates Miller’s written text as voice-overs which become so excessive that, at one point, Dwight seamlessly takes over his internal monologue, speaking it aloud within the diegesis. Unlike This Is Not a Love Song, in which the voice-over fractures Heaton’s superficially confident and competent masculinity, this sequence displays Sin City’s hysterical investment in psychic unity and continuity. Whereas the former film plays with and explores the homoeroticism of film noir, the latter reduces sexuality to displays of elaborately costumed gun-toting prostitutes, an armed and naked lesbian parole officer and a stripper packing six-shooters, betraying a not entirely unconscious homosexual panic through the over-performance of heterosexual masculinity and repeated assaults, both verbal and physical, on male genitals.

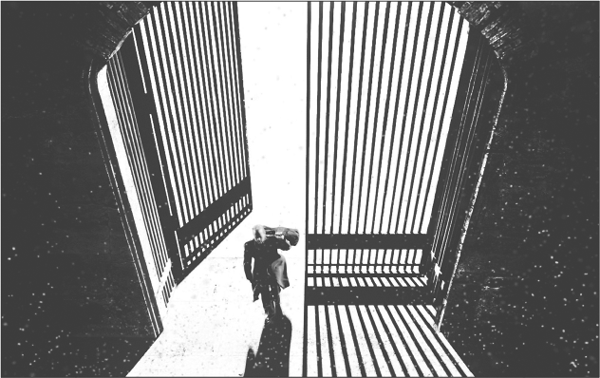

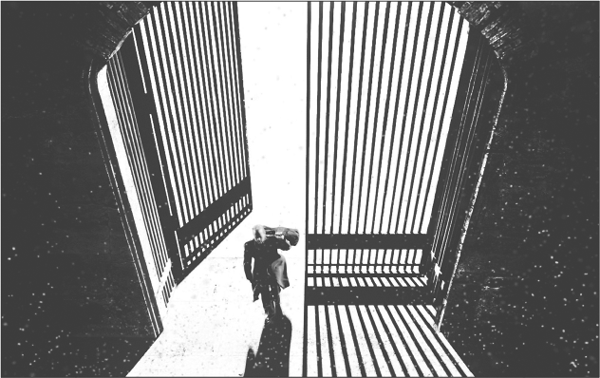

FIGURE 10 Noir image: Sin City (2005)

However, it is not merely the comic book that Sin City remediates. In many spectacle-driven movies, computer-generated imagery (CGI) is utilised to show everything, to render entire worlds visible, as with the vertiginous depths of the city in Star Wars: Episode 2 – Attack of the Clones (2002). But this impulse is frequently denied in Sin City as it uses digital technology to recreate analogue effects. For example, in the opening vignette, which is set on a roof terrace high over the city, the background is often out of focus behind the sharp foreground images of the actors. Similarly, when Hartigan drives to the waterfront to rescue young Nancy, he does so in front of a digitally created backdrop which looks like an old-fashioned back-projection. Both of these immediacy-effects are instructive in that they do not claim to offer a more direct experience of the real but, like the verité camerawork in This Is Not a Love Song, a familiar and thus authenticating visual language or representation. At other times, Sin City’s seems anxious about such recreations, becoming overly parodic, even cartoonish. At these moments, the impulse to erase the new medium ‘so that the viewer stands in the same relationship to the content as she would if she were confronting the original medium’ (Bolter and Grusin 1999: 45) conflicts with the impulse ‘to emphasise the difference rather than erase it’ (1999: 46), as the opening vignette makes clear. As The Man holds the woman he has killed, the image switches to a white-on-black silhouette, replicating a frame from ‘The Customer Is Always Right’. This comic book moment is followed by a crane shot that only CGI could achieve, the virtual camera rising up from the roof terrace, spiralling around skyscrapers and up into the sky to look down on this Manhattan-like district whose contours spell out ‘Sin City’ in a font familiar from Miller’s comic books.

Returning to Wayne’s argument about the hollowed-out aesthetics of Dark City, one can see in Sin City’s simple linear narratives and one-dimensional characters a reduction of film noir to its image(s) and the desire not to make a film noir but to somehow put the very idea, the megatext, of film noir on the screen. In contrast, This Is Not a Love Song creates an aesthetics out of economic necessity, cannibalising past styles while innovating at the edges of what its technology permits (for example, the tripping sequence consists of colour-reversed footage shot with an off-the-shelf digital lens which could operate detached from the body of the camera and thus could be fixed to the end of a fishing rod). In this sense, This Is Not a Love Song is a film noir while Sin City merely looks like one.

This judgement, however, too closely matches a knee-jerk preference for ‘realist’ over ‘fantastic’, ‘independent’ over ‘studio’, low-budget over big-budget, European over Hollywood filmmaking to be persuasive. These rough binaries should rather be seen as different modes through which film noir continues to evoke the absurd and impenetrable world of late capitalism. For all its ambiguities, This Is Not a Love Song is a love story, although its protagonists are trapped within the socially-constructed subjectivities which deny their love. Likewise, the crude certainties of Sin City – its depictions of armoured masculinity and eroticised femininity, its various detectives’ ability to trace crimes to unambiguous individual sources – are so hyperbolic, the milieu so knowable, as to completely separate this hermetic metrocosm and its continuous, unified subjects from reality. And even though the realist impulse and aesthetics of This Is Not a Love Song might seem to directly address ‘existential crisis’, it is through its various remediations that it becomes as effective an expression as Sin City of a cultural moment which shies away from exploring depth. Both films fetishise surface and superfice, generating what complexity they can from the proliferation of images and sounds. If their aesthetics are empty shells, they nonetheless connect to the moment.

Such remediations are recommodifications, images and styles repackaged and resold as capital exfoliates across levels and dimensions. But the remediation of film noir in digital films is something else, too. It is the next stage in the fabrication of the genre. To see This Is Not a Love Song and Sin City as film noirs requires us to look backward so as to validate their inclusion in the genre. Just as the Strangers reconstruct their Dark City every night to introduce small variants which might produce massive changes, so each additional film noir rethinks, reconstructs and refabricates the genre. For all the superficial unity implied by the certainty of Sin City’s visual style and by yet another book about the genre, film noir, like the subjects it depicts, is discontinuous and disunified – strapped into and bound by a plot no one could predict, condemned to ride the streetcar until the last stop.