NOTEBOOK/FUJIWARA, AIKO

DATE: 2006年9月19日

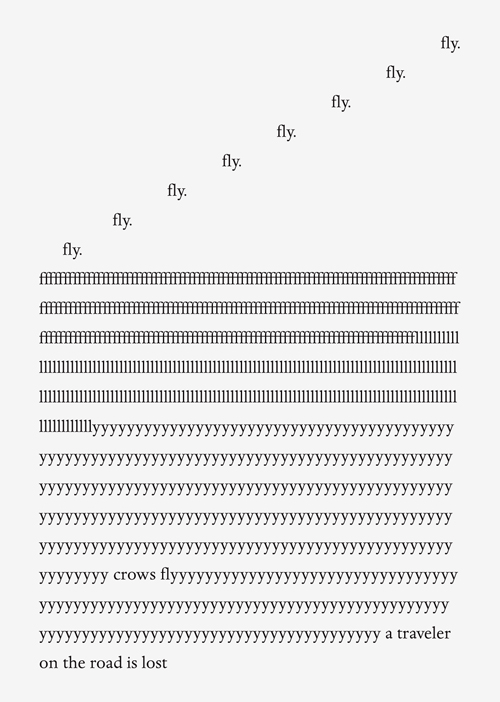

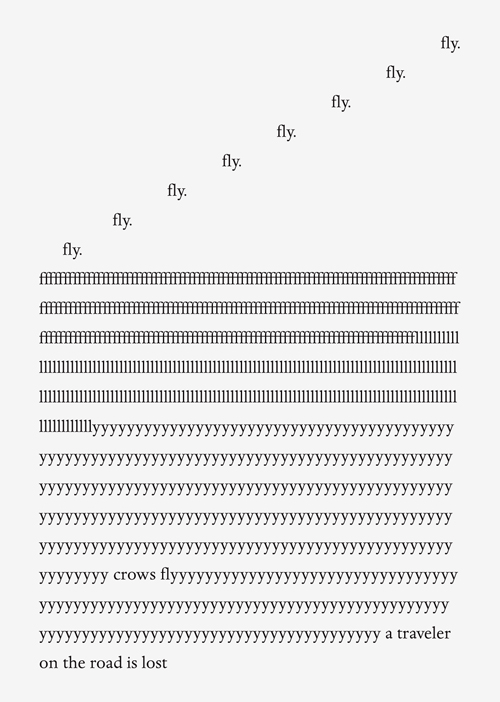

my hair hurts. my eyes hurt. everywhere i look i see them. watching me. perched outside my window perched on the fence perching perching watching watching. i watch him watching them watching me. it makes my eyes hurt. it makes my skin push and pull. fly away black bird. fly away. i didnt hurt you. i didnt know you then you came and perched and watched and perched and hurted. someone is angry. thats why he sent you. the angry one. you have no teeth. you have no arms. but he does. Hhhhhhhhhhhhheeeeeeeeeeeee dddddddddddddoooooooooeeeeeeesssssssssssssssss. i am hurting. you are hurting. he is hurting us. black feathers no shine. strong feet cracked broken. deep eyes cloudy blind. so beautiful. so lovely. where is the crow with three legs? why wont he save us? fly away, black birds. fly to places he can never find. i will follow. fly away from here.

Yori hadn’t lifted a lot of files from the town hall basement. There was a report about the headmaster’s suicide at Ōmura Shrine. There was an interview between a social worker and Seimei just after his parents died in the 1930s. And there was Aiko’s journal. The official files on the Yamabuki Three had already been moved to some central police station in Kōchi City.

More than anything else, the journal reached out to me. It was like the book was sewn together from the chills that run up your spine on a cold night. Aiko had obviously spent a lot of time decorating the front cover. The three-legged crow was carefully drawn and painted like some kind of tribute. She must have done that while she was still thinking clearly. As the journal went on, her writing became more and more muddled. At the end, she was just furiously scribbling crows with dark lines shooting out of their eyes.

I slid the journal under my futon and turned over the last item in the manila envelope. A single wristwatch fell out. We all have secrets. Moya didn’t want to tell me about the shrine fire? Well, I didn’t want to tell her about the memory I might have found. Not yet, anyway. Not until I knew for sure. I poked the watch with my finger. It wasn’t particularly cold. Other than the face being cracked, there was nothing strange about it. Maybe the trauma trapped inside had faded.

“Okay, so how do I do this?” I said to myself. “How do I start the cold dream?”

I picked the watch up and turned it over. Nothing happened.

“Maybe if I had a phrase or something? Maybe ‘Genkaku Power Go!’”

Did I just shout that in my bedroom at eleven at night?

Yep, my brain said.

“That did not work at all.”

It would have worked, said my brain, if you were in an anime and you were a crime-fighting princess.

“Hey, I like Sailor Moon,” I blurted out.

Can we just do this now? My own brain was getting impatient with me.

I lifted the watch into the air and closed my eyes as tight as I could.

Is it working? my brain asked.

“I don’t know. Should I, like, rub it or something?”

It’s not a genie!

“Well, usually things feel cold right before I faint.”

Does it feel cold to you?

“Not really.” I dropped my hand onto my futon. “Stealing memories—especially about death—does seem like a terrible thing to do.”

But there’s no other way to find the kappa.

“Yeah.”

Just take that part of you that feels weird about spying on someone’s misery and strangle it.

“Strangle it? That’s a harsh choice of words.”

If you want, I can do it for you. I am your brain.

“Good point, I guess. If you think you can, go ahead— Oh, see, now I feel the cold—”

I flopped forward on my futon as the world turned to ice.

From the reeds along Kusaka River, an ancient hand reached out. It could have belonged to a very unfortunate child. Small. Thick. Wrapped in turtle skin. Not the kind of hand you want to see poking around as you drunkenly stroll the edge of a river late at night.

Taiki’s father tossed his empty sake bottle into the black water. The boy had run at least this far, he reasoned. Normally Taiki hid out in an abandoned truck near the river, but he wasn’t there now. It didn’t make sense for the boy to throw a rock through the window and then run to his usual hiding spot. If he’d been thinking straight, Taiki’s father would have just waited until the boy returned home and then whipped the stupid out of him with a broom handle.

But Taiki’s father wasn’t thinking straight at all. How many times had he yelled at the boy for throwing pinecones at the side of the house? Soon he’d be throwing rocks, and then this would happen. Taiki ran fast, though, and by the time his father reached Kusaka River, the boy had already vanished.

Unfortunately for Taiki’s father, his son was nowhere near the river. But the real vandal was.

Shibaten had been hiding on the banks of Kusaka River for two centuries, feeding off the life-energy of bugs and rodents in the mud. In all that time, he’d never ventured far enough to watch a human. But then the small one came along. He sang a flattering nursery rhyme and threw cucumbers into the water. The small one was lonely. He was a throwaway, like the metal carriage he hid in at night. The small one looked over his shoulder and was constantly afraid. Like Shibaten with the crows.

But if the small one could find Shibaten, maybe the tengu could, too. Shibaten thought he might have to kill the small one and eat him. That would be the safest thing to do. The small one was sad and alone, so perhaps it would be better if he stopped existing anyway. Shibaten would decide what to do with Taiki in the future, but the fate of the man he lured out to the river tonight had already been decided.

Shibaten watched Taiki’s father as he kicked through the reeds, yelling into the darkness, screaming for the small one. The large human would draw out the crows in the area if he wasn’t silenced soon. Shibaten could break the man’s neck now. It would be so easy. Like a dry stick. The kappa pushed through the river grass.

“Who is it?” Taiki’s father screamed. “Who’s there?”

The reeds drifted in the breeze. The shadows along the bank shifted without a sound. Taiki’s father stared so hard into the darkness that he lost his balance and stumbled to the edge of the water. Taiki’s father rocked back and forth, drunken to a stupor on warm rice wine.

“Taiki!” he screamed again.

The boy he called for didn’t emerge. Something else that was small and hated did. Taiki’s father looked up and screamed for the last time.

Grabbing his wrist and shattering the watch, Shibaten yanked Taiki’s father off his feet and folded him backward until his spine popped. Shibaten was sorry that he might need to kill the young boy, so he gave him a gift—an agonizing death for the one person who tormented him most in the world. Taiki’s father groaned softly, moving his chin from side to side. The man’s spirit seemed old and sour like his breath, so Shibaten nudged his body into the water and let Kusaka River carry the folded man away.

Shibaten turned and leaped back across the freezing water. I stood on the other side, watching him through the icy air and the terror that still hung there. Shibaten crept up to an old barberry bush. He reached his hand out, and the thorny branches sank into a hole in the ground. The half-turtle, half-troll dropped to his stomach and slid into the cold darkness of the earth. The barberry rose up again, covering the entrance to Shibaten’s den.

I opened my eyes and stared at my futon with its warm electrical blanket. The broken wristwatch was tightly wedged in my fist. I forced my fingers free and brushed the murder evidence onto the tatami mats. I felt overwhelmingly tired. Maybe misery visions take their toll on you. Or maybe the week was finally catching up to me. Either way, I flopped forward and couldn’t keep my eyes from falling closed again.