Kenya: Nineteenth Century: Precolonial

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the East African interior was still a very secluded region in comparison with other areas of Africa. With its focus on the Eastern trade, neither the Swahili Arabs nor the Portuguese ventured beyond the small stretch of land along the Indian Ocean. The latter had ruled from the fifteenth to the eighteenth century but by the early eighteenth century Arabs from Oman had taken over the coastal zone near the equator. They started slowly to penetrate the interior, moving toward the Buganda kingdom near Lake Victoria, albeit by a southern route. They mostly shunned the northern stretch of land that in the twentieth century would become known as Kenya.

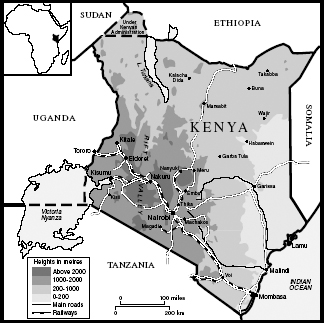

Kenya.

During the nineteenth century, Kenya underwent tremendous changes and yet also retained a degree of continuity. While the period witnessed the end of the relative isolation of African societies in the interior, it marked the reduction of the relative significance of the cosmopolitan Islamic coast. Both areas experienced a process of evolution, expansion, and differentiation that facilitated the emergence of practices and institutions which would be interrupted by colonialism at the end of the nineteenth century. However, neither the interior nor the coast showed any reduced dependence on agriculture and trade as a means of survival and stimuli for change.

Several ethnic groups varying in size, internal organization, and language, such as the Bantus, Cushites, and Nilotes, constituted nineteenth century Kenya. Patterns of life among these groups demonstrated a strong relationship between the environment and internal evolution and extra-ethnic relations. Broadly, crop production and pastoralism shaped ethnic distribution, power, and influence. They determined not only group survival and expansion but also whether a community was sedentary or nomadic. Thus, land was to crop producers what pasture and water were to pastoralists, significant aspects of group life and class differentiation on the one hand, and sources of internal and external disputes on the other.

The Bantu-speaking groups monopolized crop production since they inhabited some of the richest agricultural lands in central and southwestern Kenya. With adequate rainfall and its loam fertile soils central Kenya nurtured one of the largest Bantu groups, the Kikuyu, who with their Mount Kenya neighbors, the Embu and Meru, were fairly self-sufficient in food production. All three groups grew beans, peas, sweet potatoes, sorghum, arrowroot, and millet besides taming goats, sheep, and cattle, albeit not on a similar scale to their pastoral neighbors, the Maasai.

Agriculture fundamentally influenced the internal evolution and external relations of the Mount Kenya Bantu throughout the nineteenth century. Internally, agriculture enhanced population increase and strengthened sedentary life, the two distinct features of farming communities as compared to pastoral ones in precolonial Kenya. Also, social organization, political leadership, religious rites, and technological innovation revolved around agriculture and land. Among the Kikuyu, for example, the “office” of the Muthamaki (the head of the extended family) evolved mainly to oversee land allocation, distribution, and arbitration over land disputes.

Externally, agriculture nurtured constant trade links between the Mount Kenya Bantu and their southern neighbors, the Bantu-speaking Akamba, and the Maasai due to the semiarid conditions and the overdependency on the cattle economy. The Akamba constantly imported food from the Mount Kenya areas. This led to the creation of strong regional networks of interdependency sustained mainly by the Akamba Kuthuua (food) traders. They exchanged beer, animal skins, honey, and beeswax for the Mount Kenya staples of beans, arrowroot, and yams. Indeed, for most of the nineteenth century the Akamba played a prominent role not only as regional traders but also as long-distance (especially ivory) traders. They were intermediaries between the coastal Mijikenda and the Kenyan hinterland. From the second half of the nineteenth century their position weakened when the Zanzibar traders became involved in direct commerce in the Lake Victoria region and northern regions such as Embu, as elephants had become depleted in the more central areas. They exchanged cloth and metal rings for ivory and occasionally for slaves.

In western Kenya the Nilotic Luo and Bantu-speaking Luyhia practiced mixed farming, rearing animals, and cultivating crops. The Luo were originally pastoralists but gradually changed to mixed farming as a result of their migration to the Lake Victoria region and its attendant effects on their predominantly cattle economy. During a significant part of the nineteenth century their social, economic, and political institutions, like those of the Mount Kenya people, revolved around the importance attached to land. Increased pressure on land and subsequent disputes orchestrated the evolution of Pinje, quasipolitical territorial units, among the Luo. The Pinje enhanced corporate identity besides protecting corporate land rights. External aggression toward their neighbors, particularly the Nilotic Nandi, Luyhia, and Gusii, added further impetus to the Luo identity in the nineteenth century. Kalenjin inhabitants (Sebei groups) of the Mount Elgon area were similarly involved in intensive intertribal warfare throughout the nineteenth century with neighboring groups, mostly Karamojong, Nandi, and Pokot pastoral groups. The Luyhia, like their Luo and Kalenjin counterparts in western Kenya, were also characterized by internal rivalry and external confrontation with neighbors over land and pasture. Among the major causes of the fighting were periodic droughts and famine; the latter occurring at least once every decade.

Some sections of the Luyhia, such as the Bukusu, kept animals while others such as the Kisa, Maragoli, Banyore, and Marama practiced farming. The less numerous and isolated Bantu-speaking Gusii further up the highlands of southwestern Kenya underwent similar economic changes to those of the Luo and Luyhia. Once avowed pastoralists when living on the Kano Plains of the Lake basin, they gradually lost their affinity with cattle with their migration to the present-day Gusii Highlands. They turned to crop production and reduced the numbers of animals they kept. Regional trade that involved the exchange of goods produced by different groups provided interethnic linkages and coexistence that mitigated against land-based conflicts among the various ethnic groups of western Kenya in the nineteenth century.

Providing an economic contrast to the Bantu-dominated agriculture were the Nilotic-speaking ethnic groups such as the Turkana, Nandi, and Maasai, who practiced pastoralism. They controlled large chunks of territories in nineteenth century Kenya partly because of the requirements of the nomadic pastoralism they practiced and their inherent militarism. Of all the pastoral groups in Kenya the Maasai were a power to be reckoned with. Their force had risen since the eighteenth century and culminated in a complex southward movement by Maa-speakers from the area to the west and south of Lake Turkana south to present-day Tanzania. By doing so they conquered, assimilated, and pushed aside other groups in the Rift valley.

However, unlike the Kikuyu who enjoyed increased prosperity and demographic increase, Maasai power declined tremendously during the nineteenth century in the face of climatic disasters that annihilated their predominantly cattle economy, internal strife that led to the partition of the Maasai into contending groups, and human and animal epidemics that reduced their population and cattle stocks. The Maasai were weakened by the succession disputes of the last years of the nineteenth century. At the dawn of colonialism they had been replaced by the Nandi who emerged as the dominant power in western Kenya and resisted European penetration. In the northeast a similar change of power occurred. Since the sixteenth century Galla pastoralists had aggressively expanded southward from southern Ethiopia and Somalia. They finally reached Mombasa and occupied the lowland areas behind the coastal strip. By the middle of the nineteenth century, however, the Galla, weakened by disease, had suffered several defeats at the hands of the Somali and gradually withdrew. Drought and rinderpest epidemics that swept through their cattle in the last decades of the century weakened them still further. This allowed the Mijikenda, although they suffered periodically from cattle raids by Maasai groups, to move slowly outward from the coastal zone in the latter half of the nineteenth century.

The Kenyan coast, unlike the interior, had experienced historical links with the outside world long before the nineteenth century. The Arabs dominated the area from the tenth century onward with an interlude of-Portuguese rule and economic monopoly during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. With the ousting of the Portuguese, the nineteenth century saw the reestablishment of the Oman Arabs’ rule that for economic and political reasons was consummated by the transfer of their headquarters from Muscat to Zanzibar in 1840.

The politically semiautonomous settlements and trading posts such as Mombasa, Malindi, Lamu, Pate, Faza, and Siu remained as much an enduring feature of the Kenya coast in the nineteenth century as it had been in the previous century. The towns had strong ties between themselves based on religious, linguistic, and economic homogeneity. Islam was the dominant religion in the same way that Swahili was the prevalent lingua franca. Agriculture and trade remained the backbone of the coastal economy. Mainly practiced by the rich Arab families, agriculture's economic significance continued apace with demands for agrarian produce in the Indian Ocean trade. Local trade between the hinterland and the coast was in the hands of interior middlemen and the coastal Bantu-speaking Mijikenda.

Despite the above developments, the resurgence of Zanzibar as the heart of commercial traffic and activity stimulated the gradual decline of the economic and political significance of Kenyan coastal towns. The dawn of colonialism in the 1890s added further impetus in that direction. The establishment of various colonial administrative posts in the interior, the building of the Uganda Railway (1896–1901) and the shifting of the colonial headquarters from Mombasa to Nairobi diverted attention from the coastal towns in the opening years of the twentieth century.

One of the most important discoveries that made the interior of Kenya known to the Northern hemisphere had been the confirmation of the existence of snow-capped Mount Kilimanjaro and Mount Kenya. A German missionary Johann Rebmann saw Mount Kilimanjaro in 1848. He had arrived in Kenya to assist Johann Krapf in Rabai Mpia, a small village to the northwest of Mombasa. Both worked for the Church Missionary Society (CMS) of London, a Protestant mission founded in 1799. The work of the CMS and other Christian missionaries was the main European activity in East Africa before partition.

Although Christian missionaries pioneered European entry into Kenya, they were not responsible for the establishment of European political control that came about mainly as a result of happenings outside East Africa. French-British rivalry, both in Europe where Napoleon's defeat transferred the Seychelles and Mauritius among others to Britain, and in Africa especially due to interests in Egypt, should be mentioned. This triggered a scramble for the East African interior, in particular to control the source of the river Nile. The rising power of Germany in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, resulting in claims for the Dar es Salaam region, forced Britain to act. British and German chartered companies divided mainland territories that formerly belonged to the sultan of Zanzibar. Soon Britain took over from the Imperial British East Africa Company and a boundary stretching from the coast to Lake Victoria was drawn between British and German East Africa in 1895. Thus, it took until the end of the nineteenth century for Kenya to be explored, evangelized, and finally conquered by Britain.

The arrival of European colonizers put an end to the dynamic spheres of influence and changing fortunes of the African groups. Settlers were encouraged to come to East Africa to recoup some of the costs incurred in the construction of the Uganda railway. Soon Kenya was to be transformed from a footpath a thousand kilometers long into a colonial administration that would redefine internal power.

See also: Kenya: East African Protectorate and the Uganda Railway; Religion, Colonial Africa: Missionaries; Rinderpest, and Smallpox: East and Southern Africa.

Further Reading

Beachy, R. W. A History of East Africa, 1592–1902. London: Tauris, 1996.

Krapf, J. L. Travels, Researches, and Missionary Labors during an Eighteen Years’ Residence in Eastern Africa. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1860.

Ochieng’, W. R. A History of Kenya, London: Macmillan, 1985.

Ogot, B. A., ed. Kenya before 1900. Nairobi: East African Publishing House, 1976.

Oliver, R., and G. Mathew. History of East Africa. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1963.

New, C. Life, Wanderings, and Labours in Eastern Africa. 3rd ed. London: Frank Cass and Co., 1971.

Salim, A. I. Swahili-speaking Peoples of Kenya's Coast. Nairobi: East African Publishing Bureau, 1973.

Willis, J. Mombasa, the Swahili, and the Making of the Mijikenda. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993.

Kenya: East African Protectorate and the Uganda Railway

The early history of the East African Protectorate (after 1920 the Colony and Protectorate of Kenya) was intimately linked with the construction of the Uganda railway. The completion of the railway had an immense impact on the protectorate.

The decision of the British government to formally annex Uganda as a British protectorate in 1894 necessitated the building of a railway to connect the area around Lake Victoria with the Indian Ocean coast. Nevertheless, it was not until July 1, 1895, that British authority was formally proclaimed over the territory stretching from the eastern boundary of Uganda, then approximately fifty miles west of present day Nairobi. It was called the East African Protectorate (EAP).

Having formally claimed this part of East Africa, the imperial government undertook to build the railway through the EAP for strategic and economic reasons. It was believed that a railway would help foster British trade in the interior as well as provide the means for maintaining British control over the source of the Nile. Politicians in Britain also justified the construction of the railway by arguing that it would help to wipe out the slave trade in the region. Construction of what became known as the Uganda railway began on Mombasa Island with the laying of the ceremonial first rail in May 1896. The British parliament approved a sum of £3 million for construction in August, though not without opposition from critics who claimed that the railway “started from nowhere” and “went nowhere.”

Construction began on the mainland in August, and the railhead reached Nairobi, which became the railway headquarters, in 1899. The line reached Uganda in the following year and was completed to Port Florence (later Kisumu) on Lake Victoria in December 1901. From Mombasa to Kisumu, the railway was 582 miles in length. At £5,502,592, actual expenditure far exceeded the initial provision of funds by Parliament. The cost of the line was borne by the British taxpayer. The bulk of the labor used for construction, on the other hand, was provided by “coolies” recruited in British India. Slightly more than 20 per cent of these remained in Kenya following completion of the line; they formed a portion of the Asian (or Indian) population that took up residence in the EAP.

During the period of construction, railway building preoccupied colonial officials. Conquest of the peoples occupying the EAP was not as high a priority as the completion of the rail line. The colonial conquest was thus gradual and accomplished in piecemeal fashion, beginning in earnest only after the railway's completion. The Uganda railway facilitated military operations and was indeed the “iron back bone” of British conquest. By the end of 1908, most of the southern half of what is now Kenya had come under colonial control.

When completed, the Uganda railway passed through both the EAP and Uganda Protectorate. Imperial authorities quickly recognized potential difficulties in this situation. In order to place the railway under a single colonial jurisdiction, the Foreign Office, which was responsible for the EAP until 1905, transferred the then Eastern Province of Uganda to the EAP in April 1902. This brought the Rift valley highlands and the lake basin, what later became Nyanza, Rift valley, and Western provinces, into the EAP, doubling its size and population.

A substantial portion of Rift valley highlands was soon afterward opened to European settlement. Here also the construction of the Uganda railway played a significant part. The heavy cost of construction was compounded so far as the EAP and imperial governments were concerned by the fact that the railway initially operated at a loss and the EAP generated insufficient revenue to meet the cost of colonial administration. Thus the British government was forced to provide annual grants to balance the EAP's budget. In seeking to find the means to enhance the EAP's exports and revenues, its second commissioner, Sir Charles Eliot, turned to the encouragement of European settlement. From 1902 he drew European farmers to the protectorate by generous grants of land around Nairobi and along the railway line to the west with little thought to African land rights or needs. London authorities acquiesced in Eliot's advocacy of European settlement, which eventually led to the creation of what became known as the “White Highlands,” where only Europeans could legally farm. It meant that land and issues relating to African labor played a huge part in colonial Kenya as European settlers played a significant role in its economic and political history.

Ironically, the advent of white settlers did little immediately to solve the EAP's budget deficits. Only in the 1912–13 financial year was the annual imperial grant-in-aid terminated. The EAP's improved revenues were mostly the result of increased African production for export via the Uganda railway. European settler-generated exports accounted for the bulk of those of the protectorate only after World War I.

It cannot be denied, however, that the Uganda railway played a huge part in the early history of the EAP, from paving the way for conquest of the southern portion of the protectorate to helping to determine its physical shape and the character of its population, in the form of its Asian and European minorities in particular.

See also: Asians: East Africa.

Further Reading

Hill, M. F. Permanent Way: The Story of the Kenya and Uganda Railway. 2nd ed. Nairobi: East African Railways and Harbours, 1961.

Lonsdale, J. “The Conquest State, 1895–1904.” In A Modern History of Kenya 1895–1980, edited by William R. Ochieng’. Nairobi: Evans Brothers, 1989.

Lonsdale, J., and B. Berman. “Coping With the Contradictions: The Development of the Colonial State in Kenya, 1895–1914.” Journal of African History. 20 (1979): 487–505.

Mungeam, G. H. British Rule in Kenya, 1895–1912: The Establishment of Administration in the East Africa Protectorate. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1966.

Sorrenson, M. P. K. Origins of European Settlement in Kenya. Nairobi: Oxford University Press, 1968.

Kenya: Mekatilele and Giriama Resistance, 1900–1920

The Giriama (also spelled Giryama) were one of the most successful colonizing societies of nineteenth century East Africa. From a relatively small area around the ritual center called the kaya, inland from Mombasa, Giriama settlement spread during the nineteenth century to cover a great swath of the hinterland of Mombasa and Malindi, crossing the Sabaki River in the 1890s. It was a process of expansion driven by a conjuncture of circumstances. Long-standing tensions over resource control within Giriama society were accentuated by the new opportunities for accumulation created by the rapidly expanding coastal economy and the growing availability of servile labor, female, and male. The northward expansion took the form of a constant establishment of new homesteads by men who sought to accumulate new dependents of their own, and to assert a control over these dependents that could not be challenged by others—either their own kin, or the “gerontocracy” of other elders who claimed power through association with the kaya. The ambitions and the northward expansion of these pioneers were encouraged through engagement with coastal society. This was similarly undergoing a period of northward expansion, driven by the growth of a trade with the hinterland in ivory, aromatics, and other products, and by a growing regional demand for foodstuffs that encouraged the opening up of new areas of slave-based grain cultivation.

In the early years of British rule this expansion continued, and early administrators struck an accommodation with the most successful accumulators of the Giriama society that served the very limited needs of the early colonial state. But by the second decade of the twentieth century the demands of British rule had begun to conflict with the pattern of expansion and individual accumulation on which the nineteenth-century expansion had relied. The supply of slaves and runaway slaves from the coast had dried up after the abolition of slavery. British officials at the coast were increasingly concerned over the state of the coastal economy and sought to foster new plantation ventures, as well as supplying labor for the growing needs of Mombasa. Evidence taken for the Native Labor Commission in 1912–13 identified the Giriama as an important potential source of waged labor. In October 1912 a new administrator, Arthur Champion, was appointed to improve the supply of labor from among the Giriama, partly through the exercise of extralegal coercion and bullying, which was commonly used in early colonial states to “encourage” labor recruitment, and partly through the collection of taxes, which would force young men to seek waged work. Champion tried to work through elder Giriama men but demands for tax and for young men to go out to work struck directly at the pattern of accumulation on which these men relied: they sought to acquire dependents, not to send them away to work for others. British restrictions on the ivory trade were equally unwelcome. Champion found himself and his camp effectively boycotted.

The boycott was encouraged by the activities of a woman called Mekatilele (also spelled Mekatilili) who drew on an established tradition of female prophecy to speak out against the British and who encouraged many Giriama men and women to swear oaths against cooperation with the administration. This was a complex phenomenon, for it drew on an established accommodation between women's prophecy and the power of kaya elders, and exploited tensions between old and young and between kaya elders and the accumulators who pioneered the expansion to the north, as well as on resistance to colonial rule. Mekatilele was soon arrested and sent up-country; she escaped and returned to the coast but was rearrested and removed again. Meanwhile, in reprisal for the oaths and for some rather mild displays of hostility, the colonial administration first “closed” the kaya in December 1913 and then burned and dynamited it in August 1914. British officials were quick to understand Giriama resistance as inspired by oaths, prophecy, and the power of the kaya, but this probably reveals less about Giriama motivations than it does about colonial perceptions of male household authority as essentially good and stable, and magical or prophetic power as fundamentally subversive. In truth, Giriama resistance to British demands resulted from the disastrous impact of British policies and demands upon the authority of ambitious household heads.

The destruction of the kaya coincided with the outbreak of World War I, which immediately led to renewed efforts to conscript Giriama men, this time as porters for the armed forces. Giriama resentment was further inflamed by a British plan to evict Giriama who had settled north of the Sabaki, as a punishment for non-cooperation and to deprive them of land and so force them into waged labor. In an act of routine colonial brutality, one of Champion's police, searching for young men, raped a woman and was himself killed in retaliation. Thrown into panic by the fear of a Giriama “rising,” and finding themselves in possession of an unusually powerful coercive force, British officials launched a punitive assault on the Giriama, using two full companies of the King's African Rifles. As a result, 150 Giriama were killed, and hundreds of houses burned; officials found it difficult to bring the campaign to an end since there were no leaders with whom to deal and British policy had largely eroded the power of elder men. The campaign was finally called off in January 1915. There were no military fatalities. A continued armed police presence and the threat of further military reprisals ensured the clearance of the trans-Sabaki Giriama, the collection of a punitive fine, and the recruitment of a contingent of Giriama porters for the war.

Mekatilele returned to the area in 1919, and she and a group of elder men took up residence in the kaya. This continued to be a much-contested source of ritual power, but the idealized gerontocracy of early nineteenth century society was never reconstructed, and ritual and political power among the Giriama has remained diffuse. The trans-Sabaki was settled again in the 1920s, but Giriama society never regained the relative prosperity of the late nineteenth century.

See also: Kenya: World War I, Carrier Corps.

Further Reading

Brantley, C. The Giriama and Colonial Resistance in Kenya, 1800–1920. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1981.

Spear, T. The Kaya Complex: A History of the Mijikenda Peoples of the Kenya Coast to 1900. Nairobi: Kenya Literature Bureau, 1978.

Sperling, D. “The Frontiers of Prophecy: Healing, the Cosmos, and Islam on the East African Coast in the Nineteenth Century.” In Revealing Prophets: Prophecy in Eastern African History, edited by D. Anderson and D. Johnson. James Currey: London, East African Educational Publishers: Nairobi, Fountain Publishers: Kampala, Ohio University Press: Athens.

Willis, J., and S. Miers. “Becoming a Child of the House: Incorporation, Authority and Resistance in Giryama Society.” Journal of African History. 38 (1997): 479–495.

Kenya: World War I, Carrier Corps

Despite its strategic and commercial importance to the British Empire, the East Africa Protectorate (EAP, now Kenya) was unprepared for the outbreak of World War I. The King's African Rifles (KAR) were ill-prepared to sustain conventional military operations, as until that point it had been used largely as a military police force in semipacified areas. Moreover, the KAR possessed minimal field intelligence capabilities and knew very little about the strengths and weaknesses of the German forces in neighboring German East Africa (GEA, now Tanzania). Most importantly, the KAR lacked an adequate African carrier corps, upon which the movement of its units depended.

Hostilities began on August 8, 1914, when the Royal Navy shelled a German wireless station near Dar es Salaam. General Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, commander of the Schütztruppe, which numbered only 218 Germans and 2,542 askaris organized into 14 companies, opposed the German governor, Heinrich Schnee, who hoped to remain neutral. Instead, Lettow-Vorbeck wanted to launch a guerrilla campaign against the British, which would pin down a large number of troops and force the British to divert soldiers destined for the western front and other theaters to East Africa.

On August 15, 1914, Lettow-Vorbeck defied Schnee and captured Taveta, a small settlement just inside the EAP border. Lettow-Vorbeck then launched a series of attacks against a 100-mile section of the Uganda Railway, the main transport link in EAP that ran almost parallel to the GEA border and about three days march from the German bases near Kilimanjaro. Relying largely on raids, hit and run tactics, and the skillful use of intelligence and internal lines of communication, Lettow-Vorbeck wreacked havoc upon the British by destroying bridges, blowing up trains, ambushing relief convoys, and capturing military equipment and other supplies. By using such tactics, Lettow-Vorbeck largely eluded British and allied forces for the first two years of the campaign.

Meanwhile, the British sought to resolve problems that plagued their operations in the early days of the war. A military buildup eventually resulted in the establishment of a force that numbered about 70,000 soldiers and included contingents from South Africa, Southern Rhodesia, (now Zimbabwe), and India. There also were Belgian and Portuguese units arrayed against the Germans. Captain Richard Meinertzhagen, who became chief of allied intelligence in December 1914, created an intelligence apparatus that quickly earned the reputation of being the best in the East African theater of operations.

In December 1915, the port of Mombasa received a great influx of military personnel and equipment such as artillery, armored vehicles, motor lorries, and transport animals. Many of the troops deployed to Voi, a staging area on the Uganda railway some sixty miles from the German border. General Jan Smuts, who became allied commander in February 1916, sought to launch an offensive from Voi against Kilimanjaro to “surround and annihilate” Lettow-Vorbek's forces. Rather than commit himself to a major battle, which would involve substantial casualties, Lettow-Vorbeck resorted to hit and run attacks while slowly retreating southward. During the 1916–1917 period, Smuts fought the Schütztruppe to a stalemate. In late 1917, General J. L. van Deventer assumed command of British forces in East Africa and eventually forced the Germans to retreat into Portuguese East Africa (now Mozambique). On September 28, 1918, Lettow-Vorbeck crossed back into GEA, but before he could launch a new offensive, the war ended.

Formed a few days after the outbreak of hostilities, the Carrier Corps, East African Transport Corps played a significant role throughout the East African campaign by supporting combat units in the EAP, GEA, and Portuguese East Africa. Its history began on September 11, 1914, when the Carrier Corps commander, Lieutenant Colonel Oscar Ferris Watkins, announced that he had recruited some 5,000 Africans organized into five 1,000-man units, which were subdivided into 100-man companies under the command of native headmen. Initially, enlistment in the Carrier Corps was voluntary. On June 21, 1915, however, growing manpower requirements forced the colonial authorities to pass legislation that authorized the forcible recruitment of men for the Carrier Corps.

In February 1916, the colonial government created the Military Labor Bureau to replace the Carrier Corps, East African Transport Corps. By late March 1916, this unit reported that more than 69,000 men had been recruited for service as porters. When the East African campaign moved to southern GEA at the end of that year, the demand for military porters again increased. On March 18, 1917 the colonial government appointed John Ainsworth, who had a reputation for fair dealing among the Africans, as military commissioner for labor to encourage greater enlistment. During the last two years of the war, his efforts helped the Military Labor Bureau recruit more than 112,000 men.

Apart from service in the EAP, the Carrier Corps accompanied British and allied forces into GEA and Portuguese East Africa, where they served in extremely trying circumstances. Chronic food shortages, inadequate medical care, pay problems, and harsh field conditions plagued all who participated in the East African campaign but Africans frequently suffered more than non-Africans. Agricultural production also declined because of labor shortages on European and African-owned farms.

Nearly 200,000 Africans served in the Carrier Corps; about 40,000 of them never returned. Thousands received medals or other awards for the courage with which they performed their duties. On a wider level, the Carrier Corps’ contribution to the war effort was crucial to the allied victory in East Africa; indeed, without that unit's participation, the campaign never could have been fought. In the long run, many Carrier Corps veterans became important members of society. Some used the skills learned during wartime to become successful businessmen or community leaders. Others became politically active: Jonathan Okwirri, for example, served as a headman at the Military Labor Bureau's Mombasa Depot for eighteen months, then as president of the Young Kavirondo Association and as a senior chief. Thus, the Carrier Corps not only played a vital role in the East African campaign but also facilitated the emergence of a small but influential number of economically and politically active Africans.

See also: World War I: Survey.

Further Reading

Greenstein, L. J. “The Impact of Military Service in World War I on Africans: The Nandi of Kenya.” Journal of Modern African History. 16, no. 3 (1987): 495–507.

Hodges, G. W. P. “African Manpower Statistics for the British Forces in East Africa, 1914–1918.” Journal of African History. 19, no. 1 (1978): 101–116.

——. The Carrier Corps: Military Labor in the East African Campaign, 1914–1918. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1988.

Hornden, C. Military Operations, East Africa. Vol. 1. London: HMSO, 1941.

Miller, C. Battle for the Bundu. London: Macdonald and Jane's, 1974.

Moyse-Bartlett, H. The King's African Rifles: A Study in Military History of East and Central Africa, 1890–1945. Aldershot: Gale and Polden, 1956.

Savage, D. C., and J. Forbes Munro. “Carrier Corps Recruitment in the British East Africa Protectorate 1914–1918.” Journal of African History. 7, no. 2 (1966): 313–342.

Kenya: Colonial Period: Economy, 1920s–1930s

Land, labor, and production were strongly contested arenas for the political economy of Kenya, firmly based in agriculture, during the 1920s and 1930s. The contestation revolved around the basic nature of Kenya's outward-looking economy: were its exports and revenue to be generated by European settlers or African peasants? The most important contestants were Kenya's European, Asian, and African populations, the colonial state in Kenya, and the Colonial Office in London.

Land was a bitterly contested issue in interwar Kenya as a result of the colonial state's decision to encourage European settlement in the highlands through the appropriation of large amounts of land. By the start of the 1920s, the colonial state and the metropolitan government had accepted the principle that the region known as the white highlands was reserved exclusively for European occupation. This segregated principle of landholding was challenged by Kenya Asians and Africans during the two decades. Kenya Africans not only protested against the reservation of the highlands for whites, they objected to the loss of African occupied land taken for settler use. They also complained about the land shortage in many of the African “reserves” created by the colonial state and expressed fears regarding the security of land in those reserves. Despite protests throughout the two decades, neither the colonial state nor the Colonial Office managed to appease African land grievances. The 1932 appointment of the Kenya Land Commission represented a major attempt to do so, but it failed. Its 1934 report endorsed the segregated system of land holding in Kenya, and this was enshrined in legislation by the end of the decade. It did little to reduce African land grievances. In fact, the contestation of the 1920s and 1930s made certain that land continued to be a volatile element in Kenya politics.

Labor was likewise an area of conflict as a result of the European settler demands for assistance from the colonial state in obtaining cheap African labor for their farms and estates. The state was all too willing to subsidize settler agriculture in this way, as through the provision of land. This reached a peak at the start of the 1920s, with the implementation of a decree in which the governor ordered state employees to direct Africans to work for settlers and the initiation of the kipande (labor certificate) system as a means of labor control. Protest, particularly in Britain, forced the alteration of this policy, called the Labor Circular, but the colonial state continued throughout the 1920s to encourage African men to work for settlers. This mainly took the form of short-term migrant labor or residence on European farms as squatters. However, the impact of the Great Depression altered Kenya's migrant labor system. With settler farmers hard hit by the impact of the depression, the demand for African labor was reduced and state pressure no longer required at past levels. Squatters, in particular, faced increasing settler pressure by the end of the 1930s aimed at removing them and their livestock from the white highlands.

Pressure from settlers formed a part of the broader struggle over production that marked the two decades. The end of World War I found European settler produce (especially coffee and sisal) holding pride of place among Kenya's exports. This caused the colonial state to direct substantial support to European settler production in the immediate postwar years in the form of tariff protection, subsidized railway rates, and provision of infrastructure and extension services in addition to land and labor for the settlers. The postwar depression exposed the folly of ignoring peasant production, as the Kenya economy could not prosper on the strength of settler production alone. Pressed by the Colonial Office, the colonial state turned to what was termed the Dual Policy, which aimed to provide state support and assistance to both settler and peasant production after 1922. Nevertheless, the Dual Policy was never implemented as settler production held pride of place for the remainder of the decade, particularly after the return of a favorable market for settler produce from 1924.

The Great Depression brought an end to the strength of settler production as most settlers and the colonial state itself faced bankruptcy by 1930. The colonial state sought to save settler agriculture by a variety of measures ranging from crop subsidies and a reduction in railway charges to the setting up of a Land Bank to provide loans to European farmers. At the same time, the colonial state sought to stimulate African production for domestic and external markets during the 1930s as a means of saving the colonial economy and the settlers, a course that enjoyed strong support from London. Thus the decade witnessed a greatly expanded role of the state in African agriculture from a determination of crops to be planted to attempts to control the market for African produce. The decade was characterized by the consolidation of the commercialization of peasant production in central and western Kenya in particular while settler farmers continued to pressure the state for protection of their privileged position (e.g., removal of squatter stock from their farms and directing the sale of African grown maize through the settler-controlled marketing cooperative). The state introduced coffee, previously a crop grown exclusively by whites, to African farmers, though on an admittedly minute scale. By 1939 the state's role in African production had expanded dramatically, but the contradiction between peasant and settler production had not been resolved. This and the contestation it provoked continued to characterize Kenya's political economy over the succeeding two decades, just as was the case with land and labor.

Further Reading

Brett, E. A. Colonialism and Underdevelopment in East Africa. London: Heinemann, 1973.

Kanogo, T. “Kenya and the Depression, 1929–1939.” In A Modern History of Kenya 1895–1980, edited by W. R. Ochieng’. Nairobi: Evans Brothers, 1989.

Kitching, G. Class and Economic Change in Kenya: The Making of an African Petite Bourgeoisie, 1905–1970. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1980.

Maxon, R. “The Years of Revolutionary Advance, 1920–1929.” In A Modern History of Kenya 1895–1980, edited by W. R. Ochieng’. Nairobi: Evans Brothers, 1989.

Stichter, S. Migrant Labour in Kenya: Capitalism and African Response, 1895–1975. London: Longman, 1982.

Talbott, I. D. “African Agriculture.” In An Economic History of Kenya, edited by W. R. Ochieng’ and R. M. Maxon. Nairobi: East African Educational Publishers, 1992.

Zeleza, T. “The Colonial Labour System in Kenya.” In An Economic History of Kenya, edited by W. R. Ochieng’ and R. M. Maxon. Nairobi: East African Educational Publishers, 1992.

Kenya: Colonial Period: Administration, Christianity, Education, and Protest to 1940

As in many other parts of Africa, the establishment of colonial administration formed the prelude for the spread of Christianity in Kenya. Christian missionaries, such as the Church Missionary Society (CMS), had enjoyed little success prior to the establishment of formal colonial control in 1895. It was only after the conquest and the establishment of a colonial administrative structure that Roman Catholic and Protestant missionary societies gained a foothold. Just as the process of establishing an administrative structure for the protectorate was gradual and incremental, so also was the introduction of Christianity. By the end of the first decade of the twentieth century, colonial control had been established over much of the southern half of Kenya, and missions had gained converts as well in the region under British rule. In those areas in particular, missionaries were pioneers in introducing Western-style education in Kenya. Christians who had experienced Western education became part of a new elite that gained salaried employment with the missions as teachers and pastors, or with the colonial state, as chiefs and clerks, and took the lead in economic innovation.

Moreover, Christians with Western educations played a significant part in the protest movements that emerged to challenge the policies and practices of the colonial state in Kenya prior to 1940 and to demand improved status for themselves within colonial society. Such protest movements, which did not seek an end to colonial rule, but rather reform within the system, came to the fore following the end of World War I and were most active in the areas where the missions had established the largest numbers of schools, namely central Kenya and the Lake Victoria basin. The war and its aftermath produced a number of hardships for Kenya's Africans, including higher taxes and greatly increased demands for labor from the colonial state and the colonial European settlers and for enhanced control over African workers, reduced market opportunities for African produce, and, in central Kenya in particular, heightened insecurity with regard to land. Many Kikuyu in that region had lost access to land as a result of European settlement, and in addition to a demand for the return of those lands, mission-educated men sought to pressure the colonial state so as to ensure their access to, and control over, land in the area reserved for Kikuyu occupation.

Protest emerged first in central Kenya with regard to the land issue. It was articulated by the Kikuyu Association (KA), formed in 1919 by Kikuyu colonial chiefs, and by the Young Kikuyu Association, quickly renamed the East African Association (EAA), formed in 1921 by Harry Thuku and other young Western-educated Kikuyu working in Nairobi, to protest against high taxes, measures initiated by the colonial state to force Africans into wage labor, reduction in wages for those employed, as well as land grievances. The EAA challenged the position of the KA and colonial chiefs as defenders of African interests. The organization had gained sufficient support by March 1922 for the colonial authorities to order Thuku's arrest. The latter produced serious disturbances in Nairobi and led to the banning of the EAA and the detention of Thuku for the remainder of the decade.

Nevertheless, another protest organization soon emerged in central Kenya to champion the interests of educated Christians and challenge the KA. This was the Kikuyu Central Association (KCA), formed in 1924. It was concerned with the land issue (e.g., shortage and insecurity of tenure), but the KCA also took the lead during the interwar decades in demanding a greater voice for its members in local affairs and demanding enhanced access to the means of modernization, including more schools and planting high value cash crops. In western Kenya also, the postwar period witnessed the emergence, during 1921, of a protest organization led by educated Christians in the form of the Young Kavirondo Association (YKA). It also articulated grievances such as increased taxation, low wages, and the oppressive labor policies of the colonial state. As with the KCA, leaders also advocated more schools and greater economic opportunities directly challenging the colonial chiefs as political and economic leaders in their home areas.

In addition to the forceful suppression of the EAA, the colonial administration responded to activities of these protest organizations by some concessions, such as the lowering of taxing and ending officially sanctioned forced labor for European settlers, by the introduction of Local Native Councils in 1924 where educated Africans might play a part, by making sure that such protests were confined to a single ethnic community, and by putting pressure on the missionaries to keep the political activities of their converts under control. In western Kenya, this led to recasting the YKA as the Kavirondo Taxpayers Welfare Association (KTWA) under the leadership of the CMS missionary William Owen, and the KTWA's focusing on welfare activities rather than political protest. The colonial state also co-opted some of the protest leaders; as a result some protest leaders of the 1920s became colonial chiefs by the 1930s.

Nevertheless, Western-educated men continued to take the lead in protest to 1940. As a result, some gained influence within the state structure as well as economic advantages, such as in trade licenses and crop innovation. Overall, however, these protest movements provided no real challenge to the colonial system itself. Such political and economic gains as resulted were limited. Despite consistent advocacy by the KCA, for example, little had been done by 1940 to address the increasingly serious Kikuyu land problem. Thus it is not surprising that after that date, many educated Africans turned to different forms of protest in an attempt to address African grievances and improve living conditions.

See also: Thuku, Harry.

Further Reading

Berman, B. Control – Crisis in Colonial Kenya: The Dialectic of Domination. London: James Currey; Nairobi: East African Educational Publishers; and Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 1990.

Clough, M. S. Fighting Two Sides: Kenyan Chiefs and Politicians, 1918–1940. Niwot, Colorado: University Press of Colorado, 1990.

Kanogo, T. “Kenya and the Depression.” In A Modern History of Kenya 1895–1980, edited by W. R. Ochieng.’ London and Nairobi: Evans Brothers, 1989.

Maxon, R. M. “The Years of Revolutionary Advance, 1920–1929.” In A Modern History of Kenya 1895–1980, edited by W. R. Ochieng.’ London and Nairobi: Evans Brothers, 1989.

Strayer, R. W. The Making of Mission Communities in East Africa: Anglicans and Africans in Colonial Kenya, 1875–1935. London: Heinemann, 1978.

Kenya: Mau Mau Revolt

The Mau Mau peasant revolt in colonial Kenya remains one of the most complex revolutions in Africa. It was one of the first nationalist revolutions against modern European colonialism in Africa. Unlike other subsequent nationalist revolutions in Africa, the Mau Mau revolt was led almost entirely by peasants. The majority of its supporters were illiterate peasants who fought against the British military with courage and determination. Although the revolt was eventually defeated militarily by a combination of British and Loyalist (Home Guard) forces, its impact on the course of African history was significant. It signaled the beginning of the end of European power in Africa and accelerated the pace of the decolonization process.

The roots of the revolt lay in the colonial political economy. The colonization of Kenya by Britain led to the alienation of fertile land for white settlers from peasant farmers in Central Kenya, the home of the Kikuyu. This loss of land and the subsequent proclamation of “native reserves” sealed off possible areas of Kikuyu expansion. There arose a serious land shortage in Central Province that led to the migration of landless Kikuyu peasants to live and work on European settlers’ farms as squatters in the Rift valley.

In the Kikuyu reserve, there were social tensions over land as corrupt chiefs and other landed gentry proceeded to acquire land at the expense of varieties of landless peasants. Some of these displaced peasants migrated to the expanding urban areas: Nairobi, Nakuru, and other townships in Central and Rift Valley provinces.

After World War II, there was widespread African unemployment in urban areas, especially in Nairobi. There was inflation and no adequate housing. A combination of these factors led to desperate economic circumstances for Africans who now longed for freedom, self-determination, land, and prosperity. The level of frustration and desperation was increased by the colonial government's refusal to grant political reforms or acknowledge the legitimacy of African nationalism. Even the moderate Kenya Africa Union (KAU) under Jomo Kenyatta failed to win any reforms from the colonial government.

From October 1952 until 1956, the Mau Mau guerillas, based in the forests of Mt. Kenya and the Aberdares and equipped with minimal modern weapons, fought the combined forces of the British military and the Home Guard. Relying on traditional symbols for politicization and recruitment, the Mau Mau guerillas increasingly came to rely on oaths to promote cohesion within their ranks and also to bind them to the noncombatant “passive wing” in the Kikuyu reserve. Throughout the war, the Mau Mau guerillas sought to neutralize “the effects of the betrayers.” The guerillas relied heavily on the “passive wing” and hence could not tolerate real or potential resisters to their cause. In order to control the spread of Mau Mau influence, the British military and political authorities instituted an elaborate “villagization policy.” Kikuyu peasants in the reserve were put into villages, under the control of the Home Guards. The aim was to deny the guerillas access to information, food, and support. The “villagization policy” led to corruption and brutality toward the ordinary civilian population by the Home Guard, whose actions were rarely challenged by the colonial government so long as they “hunted down Mau Mau.” At the end of the war, the colonial government stated that 11,503 Mau Mau and 63 Europeans had been killed. These official figures are “silent on the question of thousands of civilians who were ‘shot while attempting to escape’ or those who perished at the hands of the Home Guards and other branches of the security forces.” It had been a brutal bruising war that was destined to have long-term repercussions in Kenyan society.

The British government's response to the Mau Mau revolt aimed to strategically reinforce the power of the conservative Kikuyu landed gentry while, at the same time, proceeding to dismantle the political power of the resident white settlers. This was achieved through a combination of the rehabilitation process and a gradual accommodation of African political activities and initiatives. The overriding aim of the rehabilitation of former Mau Mau guerillas and sympathizers was to “remake Kenya” by defeating radicalism. Radical individuals detained during the period of the emergency had to renounce the Mau Mau and its aims. This was achieved through a complex and elaborate process of religious indoctrination and psychological manipulation of the detainees.

The Mau Mau revolt forced the British government to institute political and economic reforms in Kenya that allowed for the formation of African political parties after 1955. Most of the former guerillas were not in a position to influence the nature of these reforms nor to draw any substantial benefits from them. The conservative landed gentry who had formed the Home Guard had a significant influence on the post-emergency society. Since the start of counterinsurgency operations, these conservatives and their relatives had been recruited by the police, army, and the civil service. They were best placed to “inherit the state” from the British while the former guerillas and their sympathizers desperately struggled to adjust to the new social, economic, and political forces.

In postcolonial Kenya, the Mau Mau revolt has remained a controversial subject of study and discussion. The failure of the Mau Mau to achieve a military and political triumph has complicated discussions about its legacy. Former guerillas, without power and influence in the postcolonial society, have been unable to “steer the country in any direction that could come close to celebrating the ‘glory of the revolt.’” There is controversy over the role that the Mau Mau played in the attainment of Kenya's political freedom. The ruling elite in Kenya have been careful to avoid portraying the revolt as a pivotal event in the struggle for independence. This has been done while continually making vague references to Mau Mau and the blood that was shed in the struggle for independence. Related to this is the emotive issue of the appropriate treatment (and even possible rewards) for former guerrillas.

The rising social and economic tensions in Kenya after 1963 have politicized the legacy of the Mau Mau revolt. Former guerillas have been drawn into the postcolonial struggles for power and preeminence by the ruling elite. The result has been a tendency by many of the former guerillas to adapt their positions to the current political situation. Both the governing conservative elite and the radical leftist opposition have invoked the memory of the revolt to bolster their positions.

Further Reading

Barnett, D., and K. Njama. Mau Mau From Within. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1966.

Buijtenhuijs, R. Essays on Mau Mau. The Netherlands: African Studies Centre, 1982.

Clayton, A. Counter Insurgency in Kenya. Nairobi: Transafrica Publishers, 1976.

Furedi, F. “The Social Composition of the Mau Mau Movement in the White Highlands.” Journal of Peasant Studies. 1, no. 4 (1974).

Gikoyo, G. G. We Fought for Freedom. Nairobi: East African Publishing House, 1979.

Kanogo, T. Squatters and the Roots of Mau Mau. London: James Currey; Nairobi: Heinemann Kenya; Athens: Ohio University Press, 1987.

Lonsdale, J., and B. Berman. Unhappy Valley: Conflict in Kenya and Africa. London: J. Currey; Narobi: Heinemann Kenya; Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 1992.

Maloba, W. O. Mau Mau and Kenya. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993.

Tarmakin, J. “Mau Mau in Nakuru.” Journal of African History. 17, no. 1 (1976).

wa Thiong'o Ngugi. Detained. London: Heinemann, 1981.

Troup, D. W. Economic and Social Origins of Mau Mau. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 1988.

Wachanga, H. K. The Swords of Kirinyaga. Nairobi: Kenya Literature Bureau, 1975.

Kenya: Nationalism, Independence

In June 1955 the internal security situation in Kenya had improved sufficiently to enable the government to lift its ban on African political organizations. But colonywide parties remained illegal, and the Kikuyu of Central Province were excluded, except for a nominated Advisory Council of “loyalists.” The government hoped that by fostering political participation among Kenya's other African ethnic groups progress would be made by nonviolent means, and some counterbalance to Kikuyu dominance of African politics would be achieved. Equally important, the possibility of “radical” African politics and violent protest being organized at a countrywide level was minimized.

By the end of 1956, as the withdrawal of the last British soldiers on counterinsurgency duty began, so too did registration of African voters for the first African elections to Kenya's Legislative Council (LegCo). Based on the Coutts Report of January 1956, the complicated qualified franchise, and the intricacies of electoral procedure meant that African elections did not take place until March 1957, six months after those for Europeans. The European candidates had been divided into two groups, six seats being won by those who approved of African political participation, against eight won by those who did not, led by settler politicians Michael Blundell and Group Captain Llewellyn Briggs, respectively. But they soon united to consolidate their numerical advantage over the eight newly arriving African Elected Members (AEMs).

Having unseated six of the government-appointed African members and thus assured of their mandate, the AEMs, led by Mboya, had different ideas. They rejected the Lyttelton Constitution as an irrelevancy imposed under emergency conditions, demanded fifteen more African seats, and refused to take ministerial office. The European members recognized that without African participation in government there would be little chance of future stability and agreed that they would accept an increase in African representation. Accordingly, in October, Alan Lennox-Boyd, the secretary of state for colonial affairs, accepted the resignations of the Asian and European ministers. This enabled him to present a new constitution: the AEMs would gain an extra ministry and six more elected seats, giving them parity with the Europeans.

The Africans, including those elected in March 1958, rejected what they saw as the disproportionate influence that the provisions for the elections to special seats left in European hands. Following the largely unsuccessful prosecution of Mboya's group for denouncing as “traitors” the eight Africans who did stand for election to the special seats, in June 1958 Odinga sought to shift the political focus by referring to Kenyatta and others as “leaders respected by the African people” in debate in LegCo. Not to be outdone in associating themselves with this important nationalist talisman, the other African politicians soon followed suit. Thus began the “cult of Kenyatta.”

Keen to emulate political advances in recently independent Ghana, the African leaders pressed for a constitutional conference to implement their demands for an African majority in LegCo. Lennox-Boyd refused to increase communal representation, insisting that the Council of Ministers needed more time to prove itself. In January 1959, as the colonial secretary and the East African governors met in England to formulate a “gradualist” timetable for independence (Kenya's date being “penciled in” as 1975) the AEMs announced a boycott of LegCo. With the prospect that the two Asian members of the government would join the AEMs, undermining the veneer of multiracialism, Governor Baring demanded a statement of Britain's ultimate intentions for Kenya. Lennox-Boyd responded in April, announcing that there should be a conference before the next Kenya general election in 1960.

But in order for the conference to take place (scheduled for January 1960) with African participation, the state of emergency had to be lifted. By the time this occurred, on January 12, 1960, the Kenya government had enacted a preservation of public security bill that, beside enabling the continued detention and restriction of the Mau Mau “residue,” and measures to preempt subversion, deal with public meetings, and seditious publications, also empowered the governor to exercise controls over colonywide political associations in accordance with his “judgement of the needs of law and order.” This was not simply a political expedient. The defeat of Mau Mau led the Kenya government's Internal Security Working Committee to conclude in February 1958 that future challenges to stability would take the form of “strikes, civil disobedience, sabotage, and the dislocation of transport and supplies rather than armed insurrection.” An Economic Priorites Committee “to study supply problems in such an eventuality” had been set up in April 1957; that same year saw some 4,000-plus strikes of varying intensity, and Mboya made frequent threats that if African demands for increased representation were not met, “the results would be far worse than anything Mau Mau produced.”

Kiama Kia Muingi (KKM), or “Council/Society of the People,” which emerged from the Mau Mau “passive wing” in March 1955, became so widespread, and too closely resembled Mau Mau, that it was proscribed in January 1958. Only political solutions to Africans’ grievances were to be allowed. But, by December 1958, Special Branch had discovered contacts between KKM and Mboya's Nairobi Peoples’ Convention Party. Only by the end of 1959, following a concerted campaign of repression, did the “KKM crisis” appear to be resolved. As a precaution, however, Britain took the unprecedented step of resuming War Office control of the East African Land Forces, thereby removing the military from “local political interference.” The measure was announced at the constitutional conference and presented as a means of freeing up local revenue for development projects.

At the January 1960 Lancaster House Conference, the African delegates presented a united front, the result of collaboration since November. Again, the Africans pressed, unsuccessfully, for Kenyatta's release. The outcome of the conference and subsequent negotiations was the concession by Iain Macleod of an effective African majority in LegCo, plus an increase in the number of Africans with ministerial responsibility. But the fissures in the African front resurfaced over the issue of whether to accept office, Mboya rejecting the constitution as “already out of date.” By June 1960 the two major pre-independence political parties had been formed: the Kenya African National Union (KANU), principally Kikuyu, Luo, Embu, Meru, Kamba, and Kisii orientated, which boycotted the government, and the Kenya African Democratic Union (KADU), representing an alliance of the Kalenjin, Maasai, and Coast peoples.

In the February 1961 general election KANU won 67 per cent of the vote but refused to take its place in the government without Kenyatta's release, leaving KADU to form a coalition with Blundell's New Kenya Party and the Kenya Indian Congress. But the expansion of yet another Kikuyu subversive movement, the Kenya Land Freedom Army (KLFA)—many members of which also carried KANU membership cards—led the governor, Sir Patrick Renison, to press Macleod to reverse his decision on Kenyatta. It would be better, Special Branch advised, to release Kenyatta and gauge the impact of his return to Kenyan politics on the security situation while Britain was still “in control.”

Although the African politicians had used “land hunger” and the presence (since 1958) of a British military base as political sticks with which to beat the colonial authorities over the issue of “sovereignty,” a further constitutional conference in September 1961 broke down over access to the “White Highlands” because KADU rejected KANU's proposals for a strong central government, favoring instead a majimbo (regional) constitution. The “framework constitution,” settled in London in February 1962, provided in principle for regional assemblies, and appeared to ameliorate tensions. But the coalition government, formed in April 1962, served as a thin veil over KADU-KANU ethnic tensions. The KLFA had spread: its oaths became increasingly violent; “military drills” were reported; over 200 precision weapons and homemade guns had been seized; and civil war seemed imminent.

It was no mere coincidence that, within weeks of KANU's June 1, 1963, electoral victory, and Kenyatta becoming prime minister and appointing an ethnically mixed government, the British Cabinet agreed to December 12, 1963, as the date for Kenya's independence. The apparent desire of the three East African governments to form a federation meant that to maintain its goodwill, and for procedural reasons, Britain could no longer prohibit Kenya's independence.

But the prospects for a federation soon collapsed and civil war seemed likely. At the final constitutional conference in September, Sandys therefore backed KANU's proposed amendments to the constitution, making it easier to reverse regionalism at a later date, as the best means to prevent chaos.

Nevertheless, on October 18, 1963, Britain began to make preparations to introduce troops into Kenya for internal security operations and the evacuation of Europeans. The victory of the “moderates” in the KADU parliamentary group and the defection of four KADU members to KANU a week later seem, on the face of it, to have been enough to ensure a peaceful transition to independence.

See also: Kenya: Kenyatta, Jomo: Life and Government of.

Further Reading

Kyle, K. The Politics of the Independence of Kenya. London: Macmillan, and New York: St. Martin's Press, 1999.

Percox, D. A. “Internal Security and Decolonization in Kenya, 1956–1963.” Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History [forthcoming].

——. “British Counter-Insurgency in Kenya, 1952–56: Extension of Internal Security Policy or Prelude to Decolonisation?” Small Wars and Insurgencies. 9, no. 3 (Winter. 1998): 46–101.

Tignor, R. L. Capitalism and Nationalism at the End of Empire: State and Business in Decolonizing Egypt, Nigeria, and Kenya, 1945–1963. Princeton: Princeton University Press, and Chichester, 1998.

Kenya: Kenyatta, Jomo: Life and Government of

Jomo Kenyatta (c.1894–1978) was born in Gatundu, Kiambu district, probably in 1894. His childhood was quite difficult due to the death of his parents. Early on, he moved to Muthiga where his grandfather lived.

Muthiga was close to the Church of Scotland's Thogoto mission. Missionaries preached in the village and when Kamau (Kenyatta's original name) became sick, he was treated in the mission hospital. Mesmerized by people who could read, he enrolled in the mission school. He accepted Christianity and was baptized Johnstone.

Leaving Thogoto in 1922, he was employed by the Municipal Council of Nairobi as a stores clerk and meter reader. The job gave him ample opportunity to travel extensively within the municipality. The allowed him to interact with his African peers, as well as Indians and Europeans. With his motorcycle, a novelty at the time, and wearing a beaded belt (kinyata) and big hats, he became a familiar figure in the municipality. Moreover, he established a grocery shop at Dagoretti, which became a meeting place for the young African elite.

Becoming acutely aware of the plight of Africans, he decided to throw his lot with the Kikuyu Central Association (KCA). He became its secretary general at the beginning of 1928 and editor of its newspaper, Muiguithania (The Reconciler). The future of Kenya was also being hotly debated in the 1920s, with Indians being pitted against the settler community. European settlers demanded responsible government, restriction of Indian immigration into Kenya, upholding of racial discrimination, and the creation of a federation of the East and Central African British colonies. Under these circumstances, the African voice needed to be heard. KCA decided to send an emissary to England for this purpose. Kamau became their choice due to his charisma, eloquence, and education. By then, he had assumed the name Jomo Kenyatta.

Kenyatta went to England in 1929–1930 and made presentations to the Colonial Office and other interested parties. The British government appointed the Carter Land Commission to investigate the land problem that had become the bane of Kenya's political life. Again KCA dispatched Kenyatta to London in 1931, where he remained until 1946.

Life in London provided Kenyatta with many opportunities for self-improvement. He enrolled at the London School of Economics to study anthropology. He traveled widely across Europe. He met with the African diaspora in Britain, gave public lectures, and wrote to newspapers about the inequities of the colonial system. He also found the time to write his major work on the Kikuyu, Facing Mount Kenya (published 1938).

The peak event of his time in Britain was probably his participation in the Pan-African Congress in Manchester in 1945. The participants committed themselves to fighting for the independence of their respective countries.

Upon returning to Kenya in 1946, he immediately became president of the Kenya African Union (KAU), which had been formed in the same year. His return initiated a new era in Kenyan politics. Here was a man who had lived in Britain for fifteen years and married a white woman, Edna Clarke. To many Kenyans, Kenyatta knew the white man's secrets and would use this knowledge to liberate them from the colonial yoke. His tour of the rural areas to popularize KAU attracted huge crowds.

As the clamor for uhuru (independence) gained momentum, two camps emerged within KAU. Kenyatta was a constitutionalist, while a faction of younger, more radically minded members, advocated for armed struggle. They began to prepare for a war of liberation by recruiting others into their movement, called the Land and Freedom Army, although it soon acquired the name Mau Mau. Initially, recruitment was through persuasion but increasingly it was carried out by force. Hence, violence escalated, and the colonial government declared a state of emergency on October 20, 1952, after the murder of Chief Waruhiu Kungu in broad daylight. Kenyatta, together with ninety-seven KAU leaders, were arrested. KAU leadership was accused of managing Mau Mau, a terrorist organization. Kenyatta was convicted, in what turned out to be a rigged trial, and jailed for seven years. He was interned in Lodwar and Lokitaung, in the remotest corners of Kenya. His release came only in 1961, after a swell of national and international outcry against his detention.

By 1956 the British and local military forces, supported by Kikuyu Guards, had contained Mau Mau. Nevertheless, Britain was forced to assess its role in Kenya and begin to meet some of the African demands. A series of constitutional changes were mounted and African representation in the Legislative Council gradually increased. Furthermore, the ban on political parties was lifted from 1955, albeit at the district level. These amalgamated in 1960 into the Kenya African National Union (KANU) and the Kenya African Democratic Union (KADU). The former was predominantly supported by the Kikuyu and Luo, while the latter attracted the smaller tribes, such as the Kalenjin and the coastal peoples.

Upon his release, Kenyatta unsuccessfully tried to reconcile the leaders of the two parties. He eventually joined KANU, becoming its president. KANU and KADU engaged in protracted constitutional negotiations centered on whether Kenya should be a federal or centralized state. Eventually KADU, which espoused federalism, was victorious. A semifederal system, majimbo, was accepted. In 1963 general elections were held which KANU won, ushering Kenya into independence on December 12, 1963, under Kenyatta's leadership (he was named president in 1964).

Kenyatta's government faced enormous problems. The formation of KANU and KADU was a glaring manifestation of tribalism, which threatened to tear Kenya apart as had happened to Congo. The economy was under the control of expatriates. It was also in shambles due to the flight of capital. There was rampant unemployment aggravated by landlessness. There were few well-trained and experienced indigenous Kenyans to man the civil service.

From the outset, Kenyatta preached the gospel of reconciliation and urged all Kenyans, irrespective of tribe, race, or color, to join together to work for the collective good. Thus he coined the national motto, Harambbee (pull together). In this regard, he encouraged KADU to disband, which it did in 1964, its supporters joining KANU. This reduced tribal tensions but produced an unexpected development. There emerged ideological divisions within KANU: a pro-Western wing that believed in capitalism, and a pro-Eastern cohort that sought to align Kenya with socialist countries. The former was led by Kenyattta and T. J. Mboya while the latter was led by Oginga Odinga, the vice president. This culminated in the ousting of Odinga as vice president in 1966. He then formed his own party, the Kenya Peoples Union, which was predominantly supported by the Luo.

To consolidate his position, Kenyatta embarked on a series of constitutional changes. He scrapped the majimbo constitution and increased the power of the presidency, including the power to commit individuals to detention without trial. He also increasingly relied on the provincial administration for managing government affairs and this led to the decline of KANU and parliament. So long as his authority and power were not challenged, he tolerated some measure of criticism and debate.

He eschewed the socialist policies that were in vogue in much of Africa. He vigorously wooed investors and courted the Western world. His policies paid dividends in that the economy grew by more than 6 per cent during his time in office. In late 1970s, this rate of growth contracted due to the vagaries of the world economy, such as the oil crisis of 1973–1974. Equally, he made efforts to indigenize the economy by establishing bodies that offered assistance to Kenyans. These include the Industrial and Commercial Development Corporation, Kenya National Trading Corporation, and Kenya Industrial Estates, among others. This assistance has a produced a class of local entrepreneurs that is playing a significant role in the Kenyan economy.

Critical to the survival of Kenya was the problem of squatters and ex-Mau Mau. In order to gain their support, the government settled them and the squatters in former settler-owned farms. In the first ten years, 259,000 hectares of land were bought and distributed to 150,000 landless people, who were also provided with development loans and infrastructure.

Kenyatta's government abolished racial discrimination in schools, introduced curricula and exams in secondary schools to prepare children for university entrance, and made efforts to increase the number of Kenyans in universities, both local and overseas. For example, between early 1960s and late 1970s university and secondary students increased from 1,900 to 8,000 and 30,000 to 490,000 respectively. And adult literacy jumped from 20 per cent to 50 per cent in the same period.

Kenyatta died on August 22, 1978. By then, he had provided Kenya with peace and stability for fifteen years. In a continent ravaged by war and coups, this was no small achievement. But one should not ignore the fact that corruption started to show its ugly face during his term. He relied heavily on his kinsmen, a factor that fuelled tribalism. He had fought very hard for freedom and yet became an autocrat, albeit a benign one. Few can deny that he laid a firm foundation for Kenya. He is thus referred to as mzee (respected elder) or Father of the Nation. In short, he was an exceptionally formidable and complex man.

Biography

Born Gatundu, Kiambu district, about 1894. Named secretary general of the Kikuyu Central Association (KCA), and editor of its newspaper, Muiguithania (The Reconciler), 1928. Goes to England, 1929–30. Returns the following year. Publishes Facing Mount Kenya, 1938. Participates in the Pan-African Congress in Manchester, 1945. Returns to Kenya, named president of the Kenya African Union, 1946. Convicted for the murder of Chief Waruhiu Kungu, 1952. Released due to national and international pressures, 1961. Named first president of Kenya, 1964. Died on August 22, 1978.

Further Reading

Barkan, J. D. “The Rise and Fall of a Governance Realm in Kenya.” In Governance and Politics in Africa, edited by G. Hyden and M. Bratton. Boulder, Colo.: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 1992.

Kenyatta, J. Suffering Without Bitterness. Nairobi: Government Printer, 1968.

Murray-Brown, J. Kenyatta. London: Allen and Unwin, 1972.

Widner, J. A. The Rise of a Party-State in Kenya: From ‘Harambee’ to ‘Nyayo’. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992.

Kenya: Independence to the Present

At the attainment of independence in 1963, Kenya inherited an economy that was symptomatic of most African colonial economies: a predominantly agricultural economy, a manufacturing sector whose cornerstone was import-substitution financed by foreign capital, and a transport infrastructure that was insensitive to the internal economic needs of the majority of the population. In the social arena, literacy levels were fairly low and disease patrolled the majority of households.

The government of Kenya under the first head of state, Jomo Kenyatta (1963–1978), cogently identified and declared war on the three major enemies of economic development in postindependence Kenya: illiteracy, disease, and poverty. Sessional Paper No. 10 of 1965, titled “African Socialism and Its Application to Planning in Kenya,” was promulgated as the government's blueprint for eradicating poverty, raising literacy levels, and providing health care services to the citizenry. But Sessional Paper No. 10 was more than just an economic document. It had the political taint of the Cold War era, when socialism and capitalism were struggling for economic and political space in the countries that were emerging from the womb of colonialism. Thus, besides its economic agenda, the document was also meant to appease both the radical and moderate wings of the ruling party, Kenya African National Union (KANU), by emphasizing private and government investment, the provision of free primary education as well as health care services.