Pennell, C. R. Morocco since 1830: A History. New York: New York University Press, 2000.

Moshoeshoe I and the Founding of the Basotho Kingdom

Moshoeshoe (1786–1870) was the name taken by Lepoqo, son of Kholu and her husband Mokhachane, headman of the small village of Menkhoaneng in the valley of the Caledon River, which today forms the northern boundary between South Africa and Lesotho. While the year of his birth cannot be precisely fixed, 1786 is the date accepted by modern scholars. During his long life he laid the foundations of the Kingdom of Lesotho and died acknowledged as the father of his people, the man who defended their land against the encroachment of European settlers.

His family was not especially important, though a number of stories relate that he was marked out by the influential chief Mohlomi as a man destined for greatness. As a young man he acquired the nickname Moshoeshoe (pronounced “muh-shwee-shwee”), a word suggesting the sound made by the shaving of a sharp razor. This commemorated his skill as a cattle raider who could steal animals as swiftly and silently as a razor shaves hair. His opportunity to found a kingdom came when the Caledon River valley was convulsed in the 1820s by a series of wars which smashed existing political authorities—a period retrospectively named by historians the lifaqane or difaqane. From the west Kora and Griqua raiders with horses and guns penetrated the Caledon Valley, wreaking widespread havoc as they seized cattle and children. To the north of Moshoeshoe's village, the Tlokwa people, led by Queen Regent ‘MaNtatisi and her son Sekonyela, became involved in wars with Hlubi and Ngwane chieftaincies from the neighboring KwaZulu-Natal region. These culminated in Hlubi and Ngwane invasions of the Caledon Valley in the early 1820s and a general reorientation of allegiances. Moshoeshoe emerged as an effective leader who gathered the remnants of many small groups together on the hilltop fortress of Botha-Bothe (sometimes Buthe-Buthe) in or about the year 1822. Here he successfully withstood a siege by Sekonyela's forces. In 1824 he moved his people to a more secure position, on the hilltop of Thaba Bosiu, which he defended against successive waves of attackers.

For the rest of the 1820s Moshoeshoe's primary concern was to restock his herds. Some he acquired by raiding south of the mountains into the territory of the Thembu and the Xhosa. Some he acquired by lending cows to his followers, who were allowed to milk them, while pledging that any calves that might be born would belong to the chief's herds. It was at this time that the name BaSotho (or Basuto) first began to be generally applied to Moshoeshoe's people. As his power grew, he formed new alliances, many of them cemented by marriages (his wives numbered more than 140 by the time of his death). The great accomplishment of this period was his displacement of his rival, Makhetha, who had a much better claim to inherited chieftainship. Makhetha perhaps unwisely allied himself to the Ngwane chief Matiwane and undertook a series of raids into Xhosa territory, where they were routed by a combined force of Xhosa, Thembu, and British forces. By the early 1830s Moshoeshoe had all but eliminated his rival.

The next period of Moshoeshoe's career is distinguished by the alliance he forged with Protestant missionaries of the Paris Evangelical Missionary Society whose first agents arrived in 1833. Well aware of the defeats inflicted on the Xhosa and other peoples on the eastern frontier of the Cape Colony, Moshoeshoe was pleased to have men at his capital who could communicate in writing with Cape authorities. He encouraged them to found mission stations throughout the territory he controlled. The missionaries welcomed his protection and wrote glowing tributes to his statesmanship, though they never converted him to their religion. They took his side in his wars against Sekonyela and other military rivals. During these years Moshoeshoe became increasingly powerful, partly because Sotho people who had fled to the Cape Colony during the wars of the 1820s now returned with cattle, horses, and guns they had bought with money earned working on farms. Moshoeshoe adopted a partially European lifestyle and set out consciously to modernize his kingdom by modifying many customs and traditions. He built a formidable military force armed with guns, whose centerpiece was a well-drilled cavalry.

A new chapter opened with the arrival of the first Voortrekkers (Afrikaans-speaking settlers from the Cape Colony) in 1836. Moshoeshoe took at face value their statement that they sought nothing more than safe passage through his territories. Soon, however, they began to settle near important sources of water, often claiming to have bought land from rival chiefs. In 1843, in a bid for British protection against the invaders, Moshoeshoe concluded a treaty with Governor Napier of the Cape Colony that he hoped would lay down firm boundaries. However, in 1848, a new Cape governor, Sir Harry Smith, annexed the entire region of “Transorangia.” British Resident Henry Warden fixed a new boundary line that removed most BaSotho land north of the Caledon. This led directly to a war in which Moshoeshoe's forces decisively triumphed at the Battle of Viervoet Mountain in June 1851. Not long after, Britain decided to transfer the Orange River Sovereignty to an independent Boer government. General Sir George Cathcart determined to reassert British power by attacking Thaba Bosiu in December 1852, but it was Cathcart's forces who learned firsthand what a determined resistance could be mounted by the disciplined BaSotho cavalry.

After the British withdrawal, Moshoeshoe was left to his own devices in dealing with the government of the Orange Free State. He triumphed in the first war of 1858, but was facing defeat in the long second war (1865–1868) when Britain intervened to save the kingdom by annexing it as the Crown Colony of Basutoland. Not long after the annexation, Moshoeshoe died, on March 11, 1870, revered by friend and foe alike as one of Africa's greatest statesmen.

See also: Boer Expansion: Interior of South Africa; Difaqane on the Highveld; Lesotho: Treaties and Conflict on the Highveld, 1843–1868.

Further Reading

Eldredge, E. A. A South African Kingdom: The Pursuit of Security in Nineteenth-Century Lesotho. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Ellenberger, D. F. History of the Basuto, Ancient and Modern. London: Caxton, 1912.

Hamilton, C. (ed.). The Mfecane Aftermath: Reconstructive Debates in Southern African History. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press, 1995.

Sanders, P. Moshoeshoe: Chief of the Sotho. London: Heinemann, 1975.

Thompson, L. M. Survival in Two Worlds: Moshoeshoe of Lesotho 1786–1870. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1975.

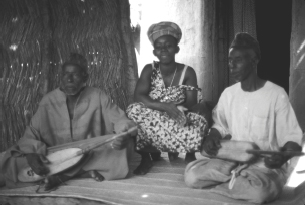

Mosque, Sub-Saharan: Art and Architecture of

The aesthetic features of the Sub-Sahara mosque owe their origins to three primary religious, cultural, and historical interpretations. First, the institution of the Friday congregational prayer, a legal Islamic requirement for all men. Second, the efficacy of vernacular building traditions, especially in relation to the Muslim Mande, Fulani, and Hausa. These three ethnolingustic groups are among the dominant Muslim populations who inhabit Sub-Sahara West Africa; they were most influential and played an active role in the cultural web of interactions, trade, diaspora, and the early nineteenth-century jihad movements.

The third explanation is more closely related to the history of Sub-Saharan medieval dynasties, that is, the Ghana, Mali, Songhay dynasties, and the later nineteenth-century Sokoto and Tukulor Caliphates. Each dynasty played host to the formation of architectural traditions in Sub-Sahara Africa. During the reign of Mansa Musa, the fourteenth-century ruler of Mali best known for his pilgrimage (hajj) to Makkah, Arabia (1324–1325), religious and educational buildings were constructed at Gao and Timbuktu. Upon his return to Mali, Mansa Musa brought an entourage of scholars from the Muslim world, among whom was an Andalusian architect and poet, Ibn Ishaq as-Sahili (d.1346 in Mali). As-Sahili is reputed to have introduced a “Sudanese” style of architecture in West Africa through the commissions granted to him by Mansa Musa. Scholars have since expressed doubt as to whether the architectural works of as-Sahili were single-handedly achieved.

A number of indigenous factors have contributed to the formation of the Sub-Sahara mosque in general and the aesthetic nuances that we find in the Mande, Fulani, and Hausa mosques in particular.

The Mande Mosque

The Mande, and in particular the Dyula, carried Islam southward from the northern savannah to the forest verges in the late eleventh and early twelfth centuries. They also carried the basic forms of the hypo-style mosque that can be found at Timbuktu, Djenne, Mopti, and San (Mali); Bobo Dialasso (Upper Volta); Kong and Kawara (Côte d'Ivoire); and Larabanga (northern Ghana). These religious edifices are a particular style of rectangular clay building, hypo-style in plan, and uniquely idiomatic in their exterior character. Formal modifications occur in the features of the mosque as it travels from north to south, from Timbuktu to the Côte d'Ivoire and northern Ghana; these modifications pertain to size scale, structure, construction details, and variations in the plan.

Compacted earth construction is used consistently with lateral timber members to reinforce the exterior walls. Protruding timber members also act as scaffolding. The exterior walls are also strengthened by buttressing or with vertical ribs. The ribs also give the appearance of decorative crenellations, termite mounds, or ancestral pillars of varying size as they terminate at the parapet. Wider ribs on the exterior facade and in the center of the qibla-wall correspond to minarets. The flat roofs are reinforced with wooden joists; this is where the muadhhin stands to summon the faithful to prayer (adhan). The courtyard (sahn) is quite small or virtually nonexistent in Sub-Sahara mosques.

The Mande distinguish three functional types of mosques: (1) the seritongo used by individuals or small groups of Muslims for daily prayers, simply an area of ground marked off by stones; (2) the misijidi (masjid), missiri, or buru serves several households for their daily prayers or for Friday prayers; (3) the jamiu, juma, or missiri-jamiu used for Friday prayers, which serves the large community.

The Fulani Mosque at Dingueraye

Amid the fervor of the nineteenth-century jihad movement in the Futa Jalon, Guinea, a unique idiom and expression of mosque architecture was born. The Fulani mosque at Dingueraye is linked to Al Hajj Umar's (Umar ibn Uthman al-Futi al-Turi al Kidiwi, 1794–1864) stay at Dingueraye from 1849 to 1853 and served one of the principal functions of a ribat, a place from which the abode of Islam (dar-al-Islam) might expand.

The Fulani mosque at Dingueraye was the first instance in which the nomadic tent and the organization of nomadic space lent themselves with the greatest of ease to a new mode of spatial orientation. Two modes of spatial orientation are evident: The first is an ambulatory space that surrounds a cube building, the actual mosque. The outer layer of the spatial enclosure is very much like the Fulani sedentary hut enclosed by a palisade wall, which demarcates an edge. In the nomadic tradition this circular space is quite evident. According to local custom at Digueraye this outer layer is changed every seven years, at which time an elaborate ceremony is held for the occasion.

The second layer of space is the cube itself, which has heavy earthen walls and an earthen ceiling supported by rows of columns. A central post supports the exterior roof structure from within the cube, like a great big tree it radiates to its outer roof. But the central post, the perimeter columns, and the thatched roof dome are structurally separate from the earthen cube within.

The mosque at Mamou and Dabola, Guinea, also has central posts that support the roof of the cube. Its inner cube has singular openings in the perimeter wall very much like the openings in Umar's sketch. The position of the central post at Dingueraye and Mamou also approximates to the central element in Umar's diagram. These spatial patterns, the elements they employ, and the image they convey can be described simply as cultural metaphors. They are also concrete renditions of Fulani spatial concepts.

The Hausa Mosque at Zaria

The mosque at Zaria was built at the end of a period of puritanical fever (jihad) and reform, and during a period of religious formation wherein the Sokoto caliphate united the Hausa states under the leadership of Uthman ibn Fodio. In the post-jihad period the ascetic scholars mainly favored the building of mosques.

None of the earlier works of Babban Gwani, a great master builder, match the architectural vitality and structural vocabulary of the vault in the Zaria mosque. However, it is very unlikely that the Babban Gwani actually invented the Hausa vault, but there is no doubt that he made the greatest and boldest use of the vault. It is very likely that Katsina, being at the forefront of Hausa custom and civilization in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries had developed the vault principles in reinforced earth technology. However, there are hardly any extant pre-jihad structures to support this hypothesis.

Professor Labelle Prussin argues that the vault is actually a synthesis of the Fulani tent armature, which was developed using Hausa skills in earth construction. The Hausa vault and dome are based on a completely different structural principle from the North African, Roman-derived stone domes. On the other hand, the Hausa domes incorporate, in nascent form, the same structural principles that govern reinforced concrete design. The bent armature in tension takes the horizontal thrust normally resisted by buttresses and tension rods and interacts with the compressive quality of earth. It was the development of this technology that permitted the transplantation of the symbolic imagery of Islam and in turn created a unique Fulani-derived architecture.

The increase in earth arch construction was particularly innovative in the post-jihad mosque at Zaria and the palaces of the period. The earth-reinforced pillars and the reinforced Hausa vaults are no commonplace construction. Very few pre-jihad buildings exhibit the structural solutions to an architectural problem of earth construction over such large spans. A more obvious solution can be found in the hypo-style mosques of Bauchi, or the Shehu mosque, Sokoto. Instead, given the program to provide a liturgical space, Babban Gwani in his organizing principle of geometry and structure derived a much more sophisticated and less formal plan than the hypo-style hall.

In determining the ceiling-type for a given building, the importance of the building, followed by the status of the patron, is brought together with the skill of the master mason. In context, a radical departure seems to have occurred from the simple trabeated type of construction which we find in the Shehu's mosque, the Kazuare mosque, and the Bauchi mosque, all built roughly in the same period (1820s) and the much later Zaria mosque (1836). The post and beam structure used to support short spans is quite commonly used in the earlier mosques, that is, Bauchi, and Shehu. They share a tradition with the Mande mosques of Mali and northern Ghana.

Further Reading

David, N. “The Fulani Compound and the Archaeologist.” World Archaeology. 3, no. 2 (October 1971): 111–131.

Denyer, S. African Traditional Architecture. New York: Heineman, 1978.

Engestrom, T. “Origin of Pre-Islamic Architecture in West Africa.” Ethnos. 24 (1959): 64–69.

Gardi, R. Indigenous African Architecture. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1973.

Leary, A. H. “A Decorated Palace in Kano.” AARP. (December 1977): 11–17.

Moughtin, J. C. Hausa Architecture. London: Ethnographica, 1985.

Moughtin, J. C., and A. J. Leary. “Hausa Mud Mosque.” Architectural Review. 137/818 (February 1965): 155–158.

Prussin, L. “The Architecture of Islam in West Africa.” African Arts. 1, no. 2 (1968).

———. “Fulani-Hausa Architecture: Genesis of a Style.” African Arts. 10, no. 1 (October 1976): 8–19; 97–98.

———. Hatumere: Islamic Design in West Africa. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986.

———. “Islamic Architecture in West Africa: The Foulbe and Manding Models.” VIA. 5 (1982): 52–69; 106–107.

Saad, H. T. “Between Myth and Reality: The Aesthetics of Traditional Architecture in Hausaland.” Ph.D. diss., University of Michigan, 1981.

Moyen-Congo: See Congo (Brazzaville), Republic of: Colonial Period: Moyen-Congo.

Mozambique: Nineteenth Century, Early

Around 1800 most of the territory that was to be delimited as the Portuguese overseas province or colony of Mozambique later that century (mainly between 1869 and 1891) was the domain of independent African states. The Portuguese territory was a string of settlements with surrounding rural estates on the coast and on the Zambezi. Portugal maintained an administrative center on the island of Mozambique and garrisons at Ibo, Quelimane, Sofala, Inhambane, and Lourenço Marques (now Maputo) on the coast and Sena and Tete on the Zambezi. Intermittently the trade posts of Macequece (Manica) and Zumbo (now Feira, in present-day southeastern Zambia) also had garrisons until 1835, when they were withdrawn owing to threats of attacks and lack of funds to sustain them. Except around Lourenço Marques, which had only been occupied definitively in 1799 or 1800 and only counted military and civilian government servants until about 1815, the settlements were composed mainly of civil populations of local, Indian, and European origin. They were surrounded in 1800 by areas of estates where inhabitants of the Portuguese towns grew some of their food and maintained many of their slaves who seemed to have constituted up to two thirds of the permanent population of the settlements. Except for the fort of Lourenço Marques and the outposts of Macequece and Zumbo, the settlements had municipal status and the free citizens elected a municipal chamber, and a justice of peace, sometimes in conflict with the local military governor. Soldiers were mostly locally recruited and some literate youths held secretarial jobs and were trained as officers.

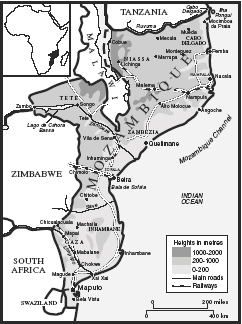

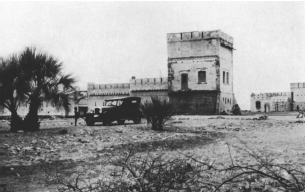

Mozambique.

Regarding commerce and trade, imports of textiles and other trade goods where paid mainly from the sale of slaves and ivory. Ivory went mostly to western India, where most of the imported cotton textiles and some of the beads for trade were obtained. Slaves were exported mainly to Brazil and French possessions (Mascareignes and the Caribbean) and from about 1837 to Spanish colonies such a Cuba. Some food staples were imported from neighboring African mainland territories and the islands of Comoro and Madagscar.

Interruptions of the trade caused by Napoleonic Wars, a temporary Brazilian import ban on slavery (effective 1831 to c.1836), the general trade depression of 1831–1833, and interference with Portuguese Indian merchant vessels as parts of the activity of the British antislavery campaign around 1840–1845 caused crises in the activity of local Portuguese and Banian (Vanya) traders. Loss of capital around 1845, its emigration around 1831–1845 paved the way to trade capital from Bombay to take a lead in Mozambique in the 1850s and for new elephant hunters and traders from the metropolis and Goa.

In the interior, African chiefs consolidated lineage states. Examples are Cee Nyambe Mataka I in Niassa, who may have started around 1825–1830 Mwaliya near Montepuez in the 1790s, Ossiwa in Alto Molocue somewhere in nineteenth century, the Khosa, Dzovo Mondlane, and the Makwakwas in modern Gaza around 1810, Yingwane and Bila-nkulu near Inhambane possibly from 1780 onward. Those in the south were overtaken by the impact of the mfecane and foundation of new states like Gaza after 1821. Near the Zambezi, descendants of traders and military officers like the Caetano Pereiras and Cruz (Bonga) who had settled in African communities the hinterland of the Portuguese estate in the later eighteenth century area emerged around 1840 as local power holders, often at the cost of local dynasties like Undi. The successors to earlier states like the Mutapa, Barue, and Uteve states maintained their internal cleavages although some candidates occasionally managed to obtain a more prominent position.

The relatively extensive coverage of local events by sources permits us to trace some major droughts and famines as result of events related to the phenomenon of el Niño around 1745–1760, 1790, 1818–1833, 1844–1845, 1855–1862, in addition to Red Locust invasions mainly during the el Niño periods, as well as smallpox and measle epidemics. This and the effects of warfare during the mfecane are supposed to have had such an effect on the population that Gaza King Soshangane was said to have ordered in 1845 to stop the export of slave from his domains.

The independence of Brazil from Portugal in 1822 inspired a revolt of soldiers on December 16, 1822, in the island capital but had few other consequences. From the point of view of Portuguese administration the most significant event ending the period of absolutist rule in the shape of the populist dictatorship of D. Miguel (c.1826–1834) was the successful liberal revolution in Portugal of 1833–1834. It happened to take place during one of the trade crises toward the end of a long period of famines, when local revenues were down and no budget support came from Portugal. Local liberals deposed and substituted governors and imprisoned of some of the most able qualified representatives of the former government. The shortage of priests increased because the new regime also abolished religious orders, retaining the parish priests on the payroll of the crown. The effect of the trade crisis of 1831–1834 is highlighted by two events in the south. The governor of Lourenço Marques, Dionísio Ribeiro, had been executed at the orders of Zulu king Dingane in October 1833. He had been reluctant to meet the Zulu kings demands of tribute from his own stores and of a private trading company. There had been no trade and almost no government funds to sustain the garrison. A year later the governor Manuel da Costa of Inhambane was killed with most of the soldiers and able bodied men from Inhambane (apparently some 280 to 1,000 men) on a foray to recover impounded ivory at a distance of about 150 to 250 kilometers from Inhambane. The settlement itself was never approached by raiders, unlike Sofala, which was attacked by Nguni chief Nqaba in 1836. As a result attempts were made to build or repair fortifications around the main Portuguese settlements except Queli-mane. (The governor of Sofala eventually shifted his administrative capital to the island of Chiloane.)

For the next decade and a half after the liberal revolution of 1834 the authority of the state institutions was very low and the attempts by military governors to reestablish their power (and possible use it for smuggling slaves) was countered by about eight isolated local revolts of the creole garrisons and settlers in the years 1840–1855, some of them apparently inspired by contemporary revolts in Portugal. Free trade policies and more direct control by the metropolis stabilized the administration after 1855. In 1834 control of movements of traders inside the colony was reduced and the establishment of Hindu and Muslim traders in the district capitals was no longer prohibited. They therefore started to spread out after 1838–1840.

Further Reading

Clarence-Smith, G. The Third Portuguese Empire, 1825–1975. Manchester: UP, 1985.

Isaacman, A. Mozambique: The Africanization of a European Institution, the Zambesi Prazos, 1750–1902. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1972.

Liesegang, G. “Dingane's Attack on Lourenco Marques.” Journal of African History. 10 (1969): 565–579.

Mudenge, S. I. A Political History of Munhumutapa. Harare: Zimbabwe Publishing House, 1986.

Newitt, M. A History of Mozambique. London: Hurst and Co., 1995.

Mozambique: Nguni/Ngoni Incursions from the South

Between the ninth and twelfth centuries, the moister summer rain areas that were adequate for millet-based agriculture in modern South Africa had been occupied by Bantu populations almost to carrying capacity and a number of processes took place to accommodate the population pressure that was building up in the areas less affected by malaria. Increase of social differentiation and of age of marriage, armed competition over farming areas and pastures, emigration and conquests, and formation of larger states seem to have been social responses to these pressures in South Africa and possibly also southern Mozambique. During this period important nuclei the ethnolinguistic or cultural formations as we now know them—Karanga (Shona), northern, eastern, and southern Sotho, Nguni, Tsonga, Tonga—seem to have been formed in southor eastern Africa. Larger states developed in the Karanga area, which extended to south of the Limpopo. Disputes over sucession and land seem to have led to immigration both of Kalanga and Nguni groups to Mozambique south of the Save River. As far as migrations and especially the Nguni group are concerned in mid-sixteenth century the Portuguese encountered already in place a number of chiefdoms in southern Mozambique who according to traditions collected in the eighteenth and twentieth centuries had immigrated from the Nguni (or Twa) areas. In pottery traditions, this identity may not always have been visible and the immigrants were assimilated also linguistically to the Tsonga Chopi and BiTonga groups in southern Mozambique.

The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries saw further groups moving north who claimed origin in the south (modern Ngwane or Swaziland and the Middelburg Ndebele areas). Most prominent were the Dzivi and Nkumbe (Cumbana) groups in Inhambane. They rapidly assimilated to the northern Tsonga (Tswa) and Bitonga and were accompanied by other groups from the Limpopo and Nkomati valleys or further south. They include the Bila or Bilankulu (Vilanculos) who had already been moving north around 1720–1730. Their spears and shields and penis sheaths distinguished them from the older Tsonga-Chopi populations north of the Limpopo using bows.

After a period of another sixty years, which registers only local dynastic quarrels and fights for hegemony, a series of campaigns and destructive wars known as mfecane in South Africa spilled over into southern Mozambique. Unlike earlier periods of invasions the mfecane one was dominated by a sociopolitical system equipped with institutions functioning to incorporate individuals and existing political structures at different places and in overlapping institutions in a new sociopolitical system. The development of this system based on an older age-class system seems to have been the result of political competition in southeastern Africa around 1810–1821 that ended with the formation of the Zulu state, which incorporated the parent Mthethwa and remnants of the Ndwandwe state complexes and extended to Swazi and Ndebele. After a period of competition between the Ndwandwe and Mtetwa states—which may have lasted for a decade—decisive clashes had come in 1819–1821. The Mtetwa led by the military commander Shaka Zulu invaded the Ndandwe kingdom after a military victory and forced important groups of the royal lineage and a number of vassal chiefs ruling parts of the kingdom to move away to the north, where at least five almost independent nuclei attempted to survive from mid-1821 onward. The groups of refugees were headed by the exiled king Zwide (who may have died c.1822) and his sons, who chose to turn back until 1827, and autonomous leaders like Ngwana Maseko, Nqaba Msane, Sochangane Nqumayo, and Zwangendaba Jere, who chose to move on and become independent heads of state. Zwangendaba may have had the position of head induna or administrator of the house of Zwide.

Zwangendaba seems to have spearheaded the advance close to the present capital of Mozambique in 1821, passing Matola and later moving to Manhiça, where from 1821 to about 1825, when he moved to the Limpopo valley. Soshangane initiated attacks in Tembe in 1821 and operated in association with Zwangendaba Jere until 1826 or 1829. Nqaba had apparently moved to the area north of the Limpopo by 1823 and in 1826 crossed into the area north of the Savé, where he founded a state that existed for about ten years. He and his warriors, many of them locally recruited, were known as “Mataos,” from which the present-day ethnic designation of Ndau is derived.

The emigration or flight of Zwangendaba from the Limpopo valley to the Venda and Zimbabwean Plateau in around 1827 or 1829, the defeat of Nqaba Msane by Soshangane around 1835–1836, the crossing of the Zambezi by Zwangendaba in 1835 and the Maseko in 1839 left the area between the Nkomati and the Zambezi to Gaza.

Parallel to the establishment of the Gaza state south of the Zambezi came the extension of Zulu rule to southernmost Mozambique from around 1824 to 1835 up to the Limpopo valley engulfing temporarily the Portuguese settlement of Lourenço Marques, which was also the aim of Swazi attacks in 1863 and 1864. The Nguni state of Swaziland exerted pressure east of the Libombos in the period 1840–1865 and maintained some presence there after the partition in 1886. Zulu military influence south of the Bay ended around 1878.

North of the Zambezi, the Nqabas group was defeated and destroyed in the upper Zambezi valley around 1840, but part of Zwangendabas followers and successors under his son Mpezeni and induna Zulu Gama managed to extend their power to Tete and Niassa provinces between 1870 and 1895. Remnants of a Maseko incursion to Niassa in around 1847/1860 stayed in present-day Niassa and Cabo Delgado provinces while the main group settled on the water-shed on the present border between Tete province and Malawi, where the colonial conquest reached them around 1898/1900, after which the could go to war only as auxiliaries in colonial wars.

The new incorporative military and age-grade system of the Nguni after 1820 permitted to establish a more permanent domination and class society with some chances of promotion for the subject population. In contacts with their superiors the subjects used the language of the victors until the defeat of the systems by the colonial conquest.

See also: Difaqane on the Highveld; Malawi: Ngoni Incursions from the South, Nineteenth Century; Mfecane; Tanganyika (Tanzania): Ngoni Incursions from the South; Zambia: Ngoni Incursion from the South; Zimbabwe: Incursions from the South, Ngoni and Ndebele.

Further Reading

Etherington, N. The Great Treks: The Transformation of Southern Africa, 1815–1854. London: Longman Pearson Eduction, 2001.

Hamilton, C. (ed.) The Mfecane Aftermath: Reconstructive Debates in Southern African History. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press, 1995.

Liesegang, G. “Nguni Migrations between Delagoa Bay and the Zambesi, 1821–1839.” African Historical Studies. 3 (1970): 317–337.

Newitt, M. A History of Mozambique. London: Hurst and Co. RITA-FERREIRA, A. 1974: Etnohistória de Cultura Tradicional do grupo Angune (Nguni). L. M. Memórias do Instituto de Inv. Cient. de Moç. II (247 pp.).

Mozambique: Colonial Period: Labor, Migration, Administration

Although Portugal established a presence in southern Africa long before any of the other European powers, it never had sufficient financial power or people to create a viable administration or to promote economic development. Even the establishment of effective occupation by reason of conquering the indigenous Africans was only completed in 1919. Early attempts to provide a foundation for that occupation and to promote some economic activity followed the Iberian pattern in the American colonies. Areas of northern Mozambique were granted to individuals in the form of prazos, within which the prazeiros had complete control; the right to exploit natural resources and people for their own profit, and in return for the payment of some taxes. The prazos were later replaced by three chartered companies, but Portugal's hold over Mozambique remained precarious, vulnerable to threats of takeover by Cecil Rhodes and Jan Smuts and to division between Germany and Britain. European diplomatic rivalries ensured that Portugal remained the nominal imperial overlord of Mozambique, but in economic terms the colony was dominated by the neighboring Boer republics and British colonies, subsequently the Union of South Africa and, to a lesser extent, Southern Rhodesia.

Partially to promote greater economic development, partly because of the ineffectiveness of the prazo system, the Portuguese created chartered companies which replaced it. The Companhia da Moçambique was given the right for fifty years to exploit and administer some 62,000 square miles north of the Savé River, including the major port of Beira. The company's financial backers were Belgian, French, and British; many heavily involved in the Transvaal and other parts of southern Africa and including, somewhat ironically, the British South Africa Company.

The Niassa Company and the Zambesia Company were also chartered by the Portuguese. They did not have the same degree of administrative responsibility as the Mozambique Company, and their authority was such that full administrative control was exercised by the Portuguese government virtually exclusively in southern Mozambique, south of the Savé River. This included the port of Lourenço Marques-Maputo on Delagoa Bay, one of the finest natural harbors on Africa's East Coast. That port was the starting point of the development of the economic links with the Transvaal and South Africa which were ultimately to a subimperial relationship in which Mozambique was the subordinate partner, South Africa the dominant.

In 1869, much to Britain's dismay, the Portuguese reached agreement with the Transvaal for the construction of a road linking the republic to Delagoa Bay, finally making a reality of a nonratified treaty of 1858. The road itself was easily built and completed in 1871. The Transvaal saw Delagoa Bay not only as the nearest port of entry and exit for its trade but also, and more important, as a means of access to the coast and world trade that was outside British control. For the Portuguese, the Transvaal represented Lourenço Marques’ only hinter-land of any potential value. To further cement the links between them, the 1869 Treaty also provided for free trade between the two countries.

In the course of negotiating this treaty, the idea of building a railway as well as a road was raised. A concession for the short stretch of line within Mozambique was granted to Edward McMurdo in 1884. For a variety of reasons, including fraud and shortage of money, the line's connection to the Witwatersrand's gold fields was delayed until 1895, the same year in which two other lines linking the Rand to the Cape ports and Durban were completed.

By 1895 the MacArthur-Forrest cyanide process for separating gold from its surrounding rock had ensured the long-term viability of the Rand goldfield, although not even the most optimistic of predictions could have justified building three rail links to the mines. Politics and the understandable desire of the different ports to reap whatever benefit they could from mine-related traffic played a great role in the decision-making process.

Although the mining industry had more lines than needed, it was seriously short of workers, for whom competition had been driving up wages beyond the ability of less profitable mines to pay. In 1896 the Transvaal Chamber of Mines, formed in 1889 primarily in an effort to control the wages spiral, and the Mozambique government agreed the terms on which Mozambicans would be recruited for work. The designated recruiting organization, was the Rand (later Witwatersrand) Native Labor Association (Wenela), set up that same year by the Chamber of Mines. Mozambicans had, from at least 1850, a history of migrating to various parts of southern Africa to seek work in agriculture, construction, and diamond mining. Attracted by higher wages than they could get in Mozambique, they also sought to escape social restrictions imposed on them and, more significant, the harshness of the Portuguese forced labor system. An approved, regularized system enabled the Portuguese not only to exert some control over population movements but also brought in revenue from the capitation fees levied on each recruit; all at virtually no cost to the Mozambique government.

Mozambicans rapidly became the most important single group of workers on the Rand. They also became especially experienced, as they frequently returned to the mines or simply renewed their contracts for extended periods. In 1901, even before the Anglo-Boer War ended, their value was recognized in a temporary agreement incorporating the continued right to recruit labor in exchange for a guarantee of traffic to the railway line to Lourenço Marques and the privileged right of entry of Mozambique goods and services to the Transvaal mining region. This right was reciprocal, and over the years the value of South Africa's exports to Mozambique greatly exceed that of its imports. Ultimately, Mozambique had only its male workers to use as a lever in negotiations with its more economically powerful neighbor. Despite pressure from Natal and elsewhere to end Mozambique's privileged position, that labor remained sufficiently important (some 50 per cent or more of the Transvaal mines labor force) for the arrangements to be incorporated into a formal convention in 1909.

Although the rail link from Lourenço Marques to the mines was shorter than any other, total shipping costs were not necessarily lower. It cost substantially more to ship goods between Lourenço Marques and Europe than was the case with the Cape ports and Durban; handling facilities at Lourenço Marques were not as good, and rates on South African lines were easily manipulated to attract traffic to them. Only the formal agreement ensured that the Mozambique line got any traffic at all, and what they did get attracted the lowest tariffs.

After World War I, efforts to renegotiate the convention failed. Cancellation had little practical effect and in 1928 it was renewed. To meet South African concerns about the working of the port at Lourenço Marques, the South African government secured a measure of control over it administration. South Africa's desire to limit the number of Mozambican recruit was met by restriction on the number of times workers simply renew their contracts without returning home. The interwar period also saw the introduction of deferred pay. A portion of workers’ wages was withheld and paid through local authorities at home, ensuring the payment of taxes and generally the interjection into the local Mozambican economy of money that otherwise tended to be spent on the mines. When the price of gold was allowed to float on world markets, accumulated deferred pay was transferred in gold to the government of Mozambique at an artificially high rate of exchange. The Portuguese could then sell the gold at a profit. This arrangement continued until shortly after Mozambique became independent.

Mozambique could not necessarily rely on continuing high levels of demand for mine workers. The Rand mines only had a finite life, and the new mines opening up in the Orange Free State were not as labor intensive. Other sources of labor opened up in the 1930s with the removal of restrictions on bringing workers from tropical areas. Restrictions had been imposed because of the high susceptibility men from those areas had to illness, notably pneumonia, when they arrived on the Rand, with its relatively hostile climate. Nonetheless, Mozambicans continued to constitute a substantial portion of the Transvaal labor force.

As South Africa felt increasingly vulnerable to pressure from the spread of independence throughout Africa, allowing recruitment to continue was one way of supporting Mozambique as part of the cordon sanitaire around the apartheid state. Mozambique's independence meant that South Africa could and did restrict labor migration, more to Mozambique's detriment than South Africa's. During the antiapartheid struggle, Mozambique could not oppose apartheid too vehemently because of its vulnerability to reprisal and its continue economic subservience to South Africa.

See also: Rhodes, Cecil, J.; Smuts, Jan, C.; South Africa: Gold on the Witwatersrand, 1886–1899.

Further Reading

Duffy, J. Portuguese Africa. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1961.

Harries, P. Work, Culture, and Identity: Migrant Labourers in Mozambique and South Africa. Portsmouth, N.H.: Heinemann and London: Currey, 1994.

Henriksen, T. H. Mozambique: A History.

Katzenellenbogen, S. E. South Africa and Southern Mozambique: Labour, Railways and Trade in the Making of a Relationship. Manchester, Eng.: Manchester University Press, 1982.

Newitt, M. A History of Mozambique. London: C. Hurst, 1995.

———. Portugal in Africa. Harlow: Longman, 1981.

Mozambique: Colonial Period: Resistance and Rebellions

Mozambique was supposedly conquered by the Portuguese in the sixteenth century. However, it was not until the nineteenth century, during the “Scramble for Africa” that the Portuguese effectively colonized Mozambique. Landing at the port of Sofala on the coast of the Indian Ocean, in 1505, the Portuguese intended to exploit mineral deposits in the interior. The interior belonged to the Mwenemutapa Kingdom, rumored to have an abundance of gold deposits.

Portuguese traders and merchants were not the first foreign forces in the Mwenemutapa Kingdom. They found that Muslim traders had been trading in the area but the Portuguese used their military might and drove them away and established commercial and administrative centers at Sena, Tete, and Quelimane.

Portuguese presence in Mwenemutapa Kingdom, and indeed in the rest of Mozambique, was never accepted by Africans. In a bid to access mineral deposits, the Portuguese sent a religious mission in 1560 whose aim was to pacify and convert the king and his subjects to the Catholic religion. The mission failed and its leader was killed, as he was suspected of having nefarious intentions. Further attempts by the Portuguese to control Mwenemutapa Kingdom were futile, as they were repulsed. Resistance to Portuguese presence had begun.

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Portugal still had not effectively colonized Mozambique as the Portuguese officials entrusted with the colonizing venture were inefficient, being more interested in their own personal gain. To ensure some kind of loyalty and obligation, Portugal relied on individual settlers. These were given title deeds by the Portuguese king for lands they had coveted for themselves. From this system developed the prazo, or crown estate. The owner was known as prazeiro. These prazeiros acted as Portuguese imperial agents and were supposed to pacify the area and rule African kingdoms on behalf of Portugal. The prazos were notorious not only for land alienation but also for exploiting Africans as sources of labor and taxation.

In the seventeenth century, the Mwenemutapa was plagued by internal dissensions, which the Portuguese used to their advantage. They installed rulers of their own choice. It was this interference in the African political system, coupled with land alienation, and an oppressive and exploitative Portuguese system that sparked African resistances, rebellions, and oppositions. Even with Portuguese interference in the African political systems, Africans still resisted in order to assert their independence. Often Africans made alliances with their neighbors in a bid to oust Portuguese rule. Nhacumbiti of Mwenemutapa and Changamira of Rozwi made such an alliance in 1692, and subsequently the Portuguese were driven away. Sometimes Africans showed their resistance by attacking Portuguese commercial and administrative centers, including prazos.

The Portuguese tried to use the Catholic religion in a bid to control some of the African kingdoms. In the eighteenth century for instance, the Portuguese tried to control the Barue Kingdom in this manner. The Barue soldiers defended themselves by attacking prazos and Portuguese commercial centers. Other ethnic groups, notably Sena, Tonga, and Tawara, also resisted the Portuguese presence, protesting Portuguese interference in political and religious autonomy, and the notorious slave armies.

By the mid-nineteenth century, Afro-Portuguese prazeiros of the Zambezi valley were using their Achikunda slave armies to pursue their slave-trading activities, in defiance of Portuguese authority. By then British, French, and Boers of the Transvaal were showing increasing interest in the region of Mozambique, thus forcing the Portuguese to make strenuous efforts, during the 1860s, to bring the whole are more visibly under their control. They faced some of their strongest opposition from rebellious prazeiros who objected to this reassertion of Portuguese power. Nevertheless, a combination of military and diplomatic effort ensured that by 1875, the whole of the modern Mozambique coast was recognized by fellow Europeans as belonging to the Portuguese.

By the time of the “Scramble,” the African kingdoms were not as well organized as they had been previously. They were replete with dissentions. Taking advantage of the situation, the Portuguese regrouped and remobilized, and from 1885 began to gain control of the Mozambique interior. Portugal then proceeded to establish its oppressive colonial system based mainly on forced labor and taxation, which the Africans resisted in various forms. Africans deliberately worked slowly, sometimes feigning illness, destroying agricultural implements or burning seeds so they would not grow. Some, like Mapondera, fled to areas that were not easily reached, from where and with the support of local societies, they attacked and destroyed symbols of Portuguese oppression. These kinds of resistances laid the foundation for national liberation movements of the 1960s such as the Front for the Liberation of Mozambique (FRELIMO). At other times, peasants simply revolted, destroying symbols of exploitation and Portuguese property and burning plantations. However, these revolts tended to be sporadic and uncoordinated, and therefore easily suppressed by the Portuguese.

One of the most common causes of resistance was taxation. Africans evaded paying tax, because they did not have the means to do so. They fled or hid before tax collectors arrived. Forced labor, or chibalo, also contributed to revolts. African peasants naturally preferred to expend their energies on their own lands, but the colonial system forced them to perform manual duties for the Portuguese. Often peasants staged small scale uncoordinated revolts, save for the 1893 rebellion in Tete, which temporarily united neighboring states in destroying symbols of oppression.

From about 1884 to the early twentieth century, Mozambique witnessed several rebellions aimed at driving out the Portuguese. The Massingire rebellion of 1884 was sparked by tax resistance. The 1897 Cambuenda-Sena-Tonga was the result of a 45 per cent increase in the hut tax. Makanga opposed the Portuguese demand of two thousand males for labor, Tawara wanted to assert the independence of the Mwenemutapa and the Shona in 1904 were against forced labor policies. The rebellions, significant as they were, were ultimately quelled because they were not united or well-organized.

Between 1900 and 1962, the Portuguese continued with their oppressive colonial system based on forced labor and taxation. Thousands of Africans were sent to South African mines and Southern Rhodesian plantations.

From the 1920s through the 1950s opposition to the Portuguese took various forms that included intellectual, rural, worker, church, and finally national opposition to Portuguese colonial system. Leading assimilados and mulattos of the 1920s started a newspaper, O Africano (The African), which spoke against the injustices of the Portuguese colonial system. In the 1950s writers and poets produced works condemning the atrocities of the Portuguese system. Workers also demanded better working conditions and wages and various independent churches expressed anticolonial sentiments. Meanwhile, the rural population continued with its sporadic and uncoordinated resistances.

It was not until the 1960s, when the ethnic and opposition groups united under FRELIMO, under the leadership of Eduardo Mondlane, that there was national resistance. Adopting guerilla tactics with the support of the rural peasants, FRELIMO resisted and fought the Portuguese until Mozambique achieved liberation in 1975.

Further Reading

Birmingham, D. Frontline Nationalism in Angola and Mozambique. London: James Curry, and Trenton, N.J.: Africa World Press, 1992.

Hanlon, J. Mozambique: The Revolution Under Fire. London: Zed Books, 1984.

Isaacman, A. and B. Isaacman. Mozambique: From Colonialism To Revolution 1900–1982. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 1983.

Penvenne, J. African Workers and Colonial Racism: Mozambican Strategies and Struggles in Lourenco Marques, 1877–1962. Portsmouth, N.H.: Heinemann, 1995.

Vail, L., and L. White. Capitalism and Colonialism in Mozambique: A Study of Quelimane District. London: Heinemann, 1980.

Mozambique: Frelimo and the War of Liberation, 1962–1975

By the 1960s it was clear that the Portuguese government would not follow the precedent offered by its British and French colonial counterparts in negotiating, relatively peacefully, the terms of decolonization with the rising forces of nationalism in its African colonies, including Mozambique. Too economically underdeveloped to feel confident of retaining the neocolonial reins after its colonies’ independence, Portugal's authoritarian political system at home was also one legitimized ideologically by the myth of empire and by ingrained practices of paternalism. Nationalists in Mozambique (but also in Angola and Guinea Bissau) would have to fight for their freedom against such a recalcitrant colonial power.

In the early 1960s, Tanzania became the central base for nationalists from throughout the southern African region who had come to similar conclusions about the imperatives of their own situations vis-à-vis white minority rule. In Dar es Salaam, encouraged toward unity by the Organization of African Unity (OAU) and certain continental leaders like Julius Nyerere and Kwame Nkrumah, a number of Mozambicans-in-exile came together, drawn from various of the quasi-nationalist movements then existent in territories neighboring Mozambique, from student and other organizations that had developed, up to a point, inside Mozambique itself, and from more distant exile (elsewhere in Africa, in Europe, and in North America). They moved to form, at a founding convention in September 1962, a more unified and effective organization to be named FRELIMO, the Front for the Liberation of Mozambique (soon referred to simply as “Frelimo”). Crucial to this development was Eduardo Mondlane who returned from a career of university teaching in the United States and employment with the United Nations to accept the position of first president of the new organization.

With the OAU Liberation Committee backing and by dint of a deft handling of relationships with other potential sponsors beyond Africa, both East and West, Frelimo soon outstripped rival claimants to nationalist primacy. Thus Frelimo was to prove far more skilled than other liberation movements in the region in drawing military assistance from both the Soviet bloc and China; its diplomatic efforts would also garner it an impressive degree of international acceptance, as well as considerable practical assistance for its “humanitarian” programs, from some Western governments (notably from the Scandinavian countries and Holland), churches and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs).

Frelimo's primacy in the eyes of the OAU and others was further consolidated by the movement's advances in military terms. After the training in Algeria of its first military cadres, including Samora Machel (soon to be head of the guerrilla army and later first president of independent Mozambique), the movement launched, in 1964, an armed struggle that would soon drive the Portuguese from large parts of both the Cabo Delgado and Niassa provinces, which bordered on Tanzania. Similar efforts were at first abortive in Tete, but from 1968 Frelimo reengaged more successfully in that province (via Zambia), pushing forward in the early 1970s to the Zambezi and ultimately, bypassing an inhospitable Malawi, into the middle of the country where it began to pose some threat to the Portuguese presence in Manica and Sofala provinces.

Such was the unifying logic exemplified by Frelimo, and the advantages reaped from the consolidation of its legitimacy within Africa and beyond, that only rather marginalized alternative voices were now heard within the broad camp of Mozambican nationalism. Much more apparent were tensions within Frelimo itself. The conventional political practices that had defined the brand of nationalism prevalent elsewhere in Africa seemed ill-suited to the requirements of the guerrilla warfare that was now deemed necessary. In consequence, one wing of the movement (influenced both by its own experience inside the country and by a sympathetic awareness, in those heady days of the 1960s, of the ideas of “people's war” associated with the Chinese and Vietnamese revolutions) began to advocate a more deeply grounded process of popular mobilization. The experience of these cadres also drew them towards an anti-imperialist critique of the nature of Portuguese colonialism and of the global capitalist system that framed it, another dimension of their radicalization.

Set against this increasingly leftist, even Marxist, tendency was a nationalist politics that instead emphasized a more exclusively racial reading of the imperatives of the anticolonial struggle and a more opportunist (elitist and entrepreneurial) practice of it. The contradictions within the movement that these differences produced may have helped trigger the 1968 assassination of Mondlane in Dar es Salaam, although the actual bomb that killed the Frelimo president was traceable to the Portuguese police.

Mondlane's death was no doubt a considerable loss to the movement in the long term, albeit one difficult to measure. Like the younger colleagues who would become his successors, Mondlane was certainly moving to the left, but his continuing presence at the heart of the movement might well have moderated the autocratic tendencies that Frelimo would eventually carry into government after 1975. More immediately, however, his death and the question of the succession merely brought into sharper focus an internal power struggle, one in which Samora Machel and the progressive group around him (with valuable support from Julius Nyerere, president of Tanzania where Frelimo was then primarily domiciled) prevailed over the more conservative Uriah Simango for the leadership. This elevation of Machel, a considerable military leader and a charismatic force, to the presidency meant a positive consolidation of the practices of armed struggle as well as a confirmation of the movement's leftward trajectory.

Some historians have questioned any such account of Frelimo's forging of effective and progressive purpose during this period. They have emphasized, for example, the importance of regional and racial factors to the movement's internal politics, viewing the group that emerged to power under Machel's leadership as being marked principally by their identity as “southerners” or “mulattos.” Others have chosen to see them merely as constituting an arrogant elite-in-the-making in their own right, albeit one (some would add) self-righteously and uncritically wedded to a modernizing agenda. Such interpretations are almost certainly overstated, although, as regards the latter point, it is probably true that the very successes of the new leadership during this phase of their struggle helped blind them to certain complexities of the transformational project they would seek to realize for their country in the postliberation period.

Opinions also differ as to the extent to which Frelimo had actually rooted itself firmly in a popular base in its “liberated areas,” even in those parts of the country where it had a palpable guerrilla presence. Nonetheless, the beginnings of a project of social transformation and popular empowerment (in terms of education, health, gender roles, even production) that the leadership felt it was witnessing in these areas helped further to radicalize its views as to what a liberated Mozambique could look like under the movement's leadership. It is also true that only a relatively small percentage of the population in the northern part of the country fell under the direct influence of Frelimo activity. Yet there can be little doubt that the movement had earned for itself a substantial credibility in the minds of a large proportion of the country's overall population by the time of the Portuguese coup in April 1974.

The precise reasons for the fall of Portuguese fascism are much debated. Nonetheless, the guerrilla challenge in Africa (and not least in Mozambique) to the regime's colonial project was an especially crucial factor in both draining the Portuguese army's morale and undermining the legitimacy of Marcelo Caetano's regime at home. Frelimo had been able to weather the combination of brutal intimidation (the massacre at Wiriyamu in 1972, for example), construction of strategic hamlets, and launching of “great [military] offensives” (such as the much trumpeted “Operation Gordian Knot”) thrown at it in the early 70s. Then, even after the coup, Frelimo refused to be tempted by the neocolonial blandishments of General Spinola and instead kept the fighting alive until a more radical Portuguese government agreed both to transfer power to the movement and, as occurred in June 1975, to recognize the new nation's independence.

Fatefully, Frelimo had thus come to power with much popular support but without benefit of elections and indeed (so certain was it of its mission to further transform in socioeconomic terms the lives of its popular constituency) with a pronounced distaste for entertaining opposition to what it considered to be its noble purposes. The hierarchical tendencies implicit in its experience of the (necessary) militarization of its struggle but also imbibed from the authoritarian practices of even the most enlightened nationalist leaders elsewhere on the continent no doubt contributed to this predilection. But so too did the movement's heady pride in its victory, its self-confidence, and its unquestioning commitment to the progressive project, deemed to be at once socialist, modernizing, and developmental, that it had forged in the liberation struggle.

See also: Mondlane, Eduardo; Mozambique: Machel and the Frelimo, 1975–1986.

Further Reading

Birmingham, D. Frontline Nationalism in Angola and Mozambique. London: James Currey, 1992.

Isaacman, A., and B. Isaacman. Mozambique: From Colonialism to Revolution, 1900–1982. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 1983.

Mondlane, E. The Struggle for Mozambique. 2nd ed. London: Zed Books, 1983.

Munslow, B. Mozambique: The Revolution and Its Origins. London: Longman, 1983.

Newitt, M. A History of Mozambique. London: Hurst and Company, 1995.

Saul, J. S. (ed.). A Difficult Road: The Transition to Socialism in Mozambique. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1985.

Mozambique: Machel and the Frelimo Revolution, 1975–1986

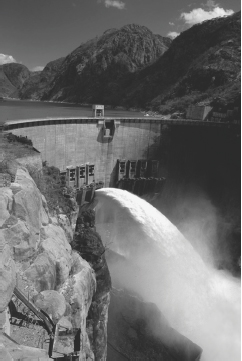

Cabora Bassa Dam, Mozambique. © Friedrich Stark/Das Fotoarchiv.

After the overthrow of the Portuguese colonial presence in Mozambique, FRELIMO (soon, as a political party, simply “Frelimo”) came to power in 1975 with an ambitious agenda highlighting nationalist, developmental and socialist goals. Although he surrounded himself with a deeply committed and unified team, the key figure in this process was undoubtedly Frelimo's president, Samora Moises Machel. Born in southern Mozambique in 1933 and trained as a nurse, Machel left Mozambique in 1963 to join FRELIMO in Tanzania. After military training, he soon rose to be head of the army and, in the wake of Eduardo Mondlane's assassination and a subsequent struggle for primacy within the movement, to its presidency in 1969. In the liberation struggle he came to play an absolutely crucial role in sustaining and advancing FRELIMO's military challenge to Portuguese rule and consolidating the movement's leftward trajectory. He was a man of enormous charisma, if also one of rather overweening self-confidence, and something of an autodidact in matters of revolutionary theory. He was deeply concerned with transforming and modernizing his country and the condition of its peoples. There can be little doubt that Machel and key leaders of Frelimo, now in positions of governmental authority, thought that this transformation would occur along socialist lines: Machel's speeches were studded with statements regarding the evils of exploitation and the nature of the global imperialist system that allow of no other interpretation of the movement's intentions.

The realization of such intentions would prove to be more difficult. The departure at independence of most of the resident Portuguese (who also engaged in substantial sabotage on leaving) created chaotic conditions, while also underscoring just how vulnerable the inherited economy was, and just how few trained Mozambicans Portuguese colonialism had produced. In addition, Mozambique was to be struck by a range of natural disasters (droughts and floods) throughout Frelimo's early years in power. The new government was prepared to be quite pragmatic in certain respects (e.g., as regards its inherited linkages with South Africa), but the various crises of the transition probably encouraged Frelimo, which in any case was extremely ambitious, to embrace too many tasks at once. Moreover, there was limited room for maneuver for progressives in power in the then polarized world of the Cold War. In such a context, Frelimo's developmental agenda was also distorted by the impact of assistance from the Eastern bloc upon which it became overly, if almost inevitably, reliant.

In the event, the movement was drawn away from the peasant roots of its liberation struggle toward a model that, by fetishizing (with Eastern European encouragement) the twin themes of modern technology and “proletarianization,” forced the pace and scale of change precipitously, both in terms of inappropriate industrial strategies and, in the rural areas, of highly mechanized state farms and (against the evidence of experience elsewhere in Africa) ambitious plans for the rapid “villagization” (“aldeias communais”) of rural dwellers. Debate continues as to how (and indeed whether) a more expansive economic development strategy that effectively linked a more apposite program of industrialization to the expansion of peasant-based production might actually have been realized under Mozambican circumstances. Nonetheless, the failure to do so was to be a key material factor in placing in jeopardy Frelimo's parallel hopes of mobilizing popular energies and transforming consciousness.

Similarly, in the political realm, the authoritarianism of prevailing “socialist” practice elsewhere reinforced the pull of the movement's own experience of military hierarchy and of the autocratic methods conventionally associated with African nationalism to encourage a “vanguard party” model of politics, this being officially embraced at Frelimo's Third Congress in 1978. The simultaneous adoption of a particularly inflexible official version of “Marxism-Leninism” had a further deadening effect on the kind of creativity (both visà-vis the peasantry during the liberation struggle and as further exemplified in the transition period by the encouragement of grassroots “dynamizing groups” in urban areas) that the movement had previously evidenced. Such developments substantially contradicted any real drive toward popular empowerment, tending to turn the organizations of workers, women, and the like into mere transmission belts for the Frelimo Party. It is true that the kind of “left developmental dictatorship” now created by Frelimo witnessed successes in certain important spheres (health and education, for example) and advances in the principles (if not always the practice) of such projects as that of women's emancipation were impressive. Moreover, the regime took seriously the challenges to their emancipatory vision posed by the structures of institutionalized religion, by “tradition” and patriarchy, and by ethnic and regional sentiment. But the high-handed manner (at once moralizing and “modernizing”) in which it approached such matters often betrayed an arrogance and a weakness in methods of political work that would render it more vulnerable to destructive oppositional activity than need otherwise have been the case.

The fact remains that the most important root of such “oppositional activity” lay in Frelimo's fateful decision to commit itself to the continuing struggle to liberate the rest of southern Africa, Rhodesia in the first instance but also South Africa, a point often downplayed by those observers who now choose to underestimate the high sense of moral purpose with which Frelimo assumed power in 1975. It was a choice for which the fledgling socialist state was to pay dearly, however. The cutting off of economic links with Rhodesia helped undermine the economy of Beira and its hinterland (especially when little of the promised international compensation for implementation of sanctions was forthcoming). And the support for ZANU guerrillas in advancing their own struggle prompted the Rhodesians to launch efforts to destabilize Mozambique, notably through the recruitment of renegade Mozambicans as mercenaries into a “Mozambique National Resistance” (the MNR, later Renamo) Then, after the fall of the Smith regime in 1979, the South African state itself chose to breathe fresh life into Renamo while intensifying the latter's cruel program of outright destabilization, characterized by its brutal targeting of Mozambican civilian populations, and its wilful destruction of social and economic infrastructures.

The conclusion carefully argued by Minter (1994: p.283) stands: that without such external orchestration, Mozambique's own internal contradictions would not have given rise to war. Once launched, however, the war did serve to magnify Frelimo's errors and to narrow its chances of learning from them. Indeed, such was the war's destructive impact on Mozambique's social fabric that what began as an external imposition slowly but surely took on some of the characteristics of a civil war. Given the nature of its own violent and authoritarian practices, Renamo could not easily pose as a champion of democracy (except in some ultraright circles in the West). Nonetheless, it had some success, over time, in fastening onto various grievances that sprang from the weaknesses in Frelimo's own project, Renamo seeking to fan the resentments of disgruntled peasants, disaffected regionalists, ambitious “traditionalists” (e.g., displaced chiefs). Meanwhile, under pressure, the Frelimo state itself buckled, its original sense of high purpose and undoubted integrity beginning to be lost. Thus, by the time open elections did finally occur in the 1990s as part of the peace process, Renamo had gained sufficient popular resonance to present a real challenge to Frelimo, albeit on a terrain of political competition reduced to the lowest kind of opportunistic calculation of regional, ethnic, and sectional advantage.

In the period covered in this entry such outcomes were not yet visible. And yet, by the early 1980s, Frelimo had begun to adapt its domestic policies in a less aggressively revolutionary, more market-sensitive direction. True, this was done (at its Fourth Congress in 1983, for example) in ways that could still be interpreted as realistic adjustments calculated primarily to ensure the long-term viability of quasi-socialist goals. In retrospect, however, they can also be seen as first steps in an effort to placate various Western actors, in particular the Reagan White House, which was now so aggressive in the region and a tacit supporter of South African strategies. By the 1990s such trends would witness a full-scale surrender by Frelimo to the globalizing logic of neoliberalism.

Just how far, had he lived, Samora Machel would himself have been prepared to travel down that road must remain a matter of speculation. Nonetheless, Machel had already presided over the movement's most humiliating capitulation, that to South Africa, as crystallized in the signing of 1984's Nkomati Accord. This pact found Frelimo trading abandonment of its support to the ANC for South Africa's promise to wind down its orchestration of Renamo's destabilizing activities. In fact, South Africa did no such thing, and Machel now proposed a (long overdue) housecleaning of state structures, in particular of the military. He was to perish, however, in October 1986, when his airplane crashed while returning from a meeting in Zambia (a crash which, some continue to claim, may have been engineered by the South Africans). Whatever the disarray and uncertainty that by now characterized Frelimo's overall project, the renowned unity of the movement's leadership core held firm. Joaquim Chissano, himself a veteran activist from the liberation struggle period, was elevated to the presidency.

Further Reading

Christie, I. Machel of Mozambique. Harare: Zimbabwe Publishing House, 1988.

Hall, M., and T. Young. Confronting Leviathan: Mozambique since Independence. Athens: Ohio University Press, 1997.

Machel, S. Samora Machel: An African Revolutionary/Selected Speeches and Writings, edited by B. Munslow. London: Zed Books, 1985.

Minter, W. Apartheid's Contras: An Inquiry into the Roots of War in Angola and Mozambique. London: Zed Books, 1994.

Saul, J. S. (ed.). A Difficult Road: The Transition to Socialism in Mozambique. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1985.

———. Recolonization and Resistance: Southern Africa in the 1990s. Trenton: Africa World Press, 1993.

Mozambique: Renamo, Destabilization

South Africa's apartheid regime responded to independence and majority rule in neighboring states with a policy of destabilization, in which it covertly fomented war and created economic problems in those states. This had three purposes: to weaken those states and prevent them from supporting the South African liberation movements, to disrupt transport links and keep the countries dependent on South Africa (and thus disrupt the newly founded Southern African Development Coordination Conference, or SADCC), and to demonstrate to its own people and the wider world that black governments were incompetent and unfit to rule. From 1981 this policy received tacit support from the U.S. administration of President Ronald Reagan, which saw which South Africa as an anticommunist bastion standing up to black “communist” governments.

Resistencia Nacional Moçambicana (Mozambique National Resistance, or Renamo) was South Africa's agent in Mozambique, and during the 1981–1992 war, at least 1 million people died, 5 million were displaced or became refugees in neighboring countries, and damage exceeded $20 billion. Renamo was initially set up by the Rhodesian security services in 1976 when Mozambique imposed mandatory United Nations sanctions against Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). Renamo's first members were Mozambicans who had been in particularly brutal Portuguese colonial units before independence, and who then fled to Rhodesia fearing punishment. Renamo made raids into central Mozambique, and built up recruits by raiding open prisons in rural areas. The main Renamo bases in Mozambique were captured in 1979 and 1980, and Renamo was largely defeated.

With independence in Zimbabwe in 1980, the remaining Renamo fighters were passed on to South African military intelligence, which set up special bases for them in northeast South Africa. Rhodesia had only used Renamo for harassment and intelligence, but South Africa built Renamo into a major fighting force with extensive training and supplies by boat and plane. South African commandos took an active part in key Renamo sabotage actions. Afonso Dhlakama was selected as the new commander. By mid-1981 Renamo was active in the two central provinces; by the end of 1983 it was disrupting travel and carrying out raids in six of the ten provinces; it required 3,000 Zimbabwean troops to protect the road, railway, and oil pipeline that linked the Mozambican port of Beira to Zimbabwe.

On March 16, 1984, Mozambique and South Africa signed the Nkomati Accord, under which South Africa agreed to stop supporting Renamo in exchange for Mozambique expelling African National Congress (ANC) members. Mozambique abided by the accord, but South Africa did not; support for Renamo was reduced but never stopped.

South Africa wanted to disrupt transport and commerce and destroy economic infrastructure in Mozambique, and it also wanted to destroy the image of the Front for the Liberation of Mozambique, popularly known as Frelimo. A central plank of its strategy was fear, and Renamo was molded into an effective terrorist force. Frelimo had gained its greatest popularity through its rapid expansion of health and education, so Renamo attacked schools and health posts and maimed, killed, or kidnapped nurses and patients, teachers, and pupils. The goal was to make people afraid to use health posts and send their children to school, and to make teachers and nurses afraid to work in rural areas, thus eliminating Frelimo's traditional sources of support. To disrupt commerce, shops were destroyed and there were brutal attacks on road and rail transport; wounded passengers were burned alive inside buses, but some were always left alive to tell what had happened, thus creating fear of travel. More than half of all rural primary schools, health posts, and shops were destroyed or forced to close.

In 1998 the United States deputy assistant secretary of state for African affairs, Roy Stacey, accused Renamo of carrying out “one of the most brutal holocausts against ordinary human beings since World War II.” Renamo, he said, was “waging a systematic and brutal war of terror against innocent Mozambican civilians through forced labor, starvation, physical abuse, and wanton killing.”

Renamo recruited largely by kidnapping large groups of young people. The Renamo members allowed the most determined of the kidnapped to escape. The rest were frightened into submission, forced to kill, and gradually molded into willing soldiers.

Travel and commerce became difficult in much of the country. By 1985, exports were only one-third of their 1981 levels, and GDP per capita was half of its 1981 level. By 1990, one-third of the population had fled to towns or neighboring countries, leaving rural areas depopulated. By 1992, the United Nations estimated that Renamo controlled 23 per cent of the territory of Mozambique, but only 6 per cent of the population.

Renamo had popular support in some areas, particularly in the center of the country. Peasants were critical of Frelimo for its opposition to “traditional leaders” and, in its rush to modernize the economy, for Frelimo's failure to adequately support the peasantry. The war and deteriorating economy turned many against Frelimo.

In 1992, after two years of negotiation in Rome, the government of Mozambique and Renamo signed a peace accord. Both sides were tired of war, and the ceasefire was quickly implemented. The peace accord implicitly accepted that there would be no truth commission, and thus no punishments would be meted out for atrocities committed during the war. Frelimo demobilized 66,000 soldiers; Renamo demobilized 24,000 adult soldiers and 12,000 child soldiers, according to the United Nations. The peace accord called for a new integrated army of 30,000 men, half from each side, but only 12,000 of the demobilized chose to join the army.

Renamo was recognized as a political party and received extensive donor support in the two years before the 1994 elections to convert it from a guerrilla force into a political party. Many people joined Renamo in that period, seeing it as the only viable opposition party.

Multiparty election on October 27–29, 1994, and December 3–5, 1999, were quite similar. Approximately two-thirds of all adults of voting age voted in each election. Both elections were declared free and fair by foreign observers who also praised the organization of the electoral process. Frelimo and its president Joaquim Chissano won both elections, but Renamo took a significant portion of the votes. Renamo boycotted the opening session of parliament after both elections, claiming fraud, but offering no evidence to support its claim.

In February 2000 southern Mozambique suffered the worst floods since 1895; 700 people died, 40,000 were saved by the Mozambique navy and South African air force, and 500,000 were displaced and assisted by the international community. Although Mozambique's per capita GDP continued to increase, the floods slowed growth in 2000, and the impact continued into 2001.

See also: Mozambique: Chissano and, 1986 to the Present; Mozambique: FRELIMO and the War of Liberation, 1962–1975; Mozambique: Machel and the Frelimo Revolution, 1975–1986; South Africa: Apartheid, 1948–1959.

Further Reading

Hanlon, J. Beggar Your Neighbours: Apartheid Power in Southern Africa. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1986.

———. Mozambique: Who Calls the Shots. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1991.

———. Peace Without Profit: How the IMF Blocks Rebuilding in Mozambique. Portsmouth, N.H.: Heinemann, 1996.

Minter, W. Apartheid's Contras: An Inquiry into the Roots of War in Angola and Mozambique. Atlantic Highlands, N.J.: Zed Books, 1994.

United Nations Department of Public Information. The United Nations and Mozambique: 1992–1995. New York: United Nations, 1995.

Vines,A. Renamo: From Terrorism to Democracy in Mozambique? London: James Currey, 1996.

Mozambique: Chissano and, 1986 to the Present