The Ayyubid state from 1193 to 1250 can best be understood as a confederation of rival principalities ruled by the extended Ayyubid family, generally under the hegemony of three sultans of Egypt: Saladin's brother al-Adil (1200–1218), his son al-Kamil (1218– 1238), and the latter's son al-Salih (1240–1249). When faced with a serious outside threat—such as a Crusader invasion from Europe—most of the rival princes united, only to again fall into bickering when the threat was removed. Saladin himself laid the foundation for this instability when, true to contemporary Near Eastern concepts of succession, he divided his empire among kinsmen, with brothers, sons and other relatives receiving semi-autonomous fiefs and principalities. With the feuding and incompetence of Saladin's sons weakening the state, Saladin's brother al-Adil (1200–1218) organized a coup, declared himself Sultan of Egypt, and established hegemony over the rival Ayyubid princes. Thereafter, although there was some expansion of Ayyubid power in northwestern Mesopotamia, for the next half century the Ayyubids generally remained on the defensive, facing two major enemies: Crusaders and Mongols.

In general, Ayyubid policy toward the Crusaders in the thirteenth century was one of truce, negotiation and concession. However, Crusader aggression aimed at recovering Jerusalem brought three major invasions. The Fifth Crusade (1218–1221) attacked Egypt and temporarily conquered Damietta, but was defeated at Mansura in 1221. Under the emperor Frederick II the Sixth Crusade (1228–1229) capitalized on an ongoing Ayyubid civil war and succession crisis, in which the Ayyubid princes of Syria and Palestine were allied against al-Kamil of Egypt. To prevent a simultaneous war against these rebellious Ayyubid princes and Frederick's Crusaders, al-Kamil agreed to cede a demilitarized Jerusalem to the Crusaders (1229). This respite provided the opportunity to force his unruly Ayyubid rivals into submission and establish himself firmly on the throne of Egypt. The last Crusader invasion of Egypt, the Seventh Crusade under Louis IX of France (1249–1251), also invaded Egypt, culminating with a great Ayyubid victory over the Crusaders at Mansurah (1250). But the untimely death of the sultan al-Salih at the moment of his triumph created a succession crisis resulting in the usurpation of power by mamluk generals, founding the Mamluk dynasty of Egypt (1250–1517).

Following the Mamluk usurpation of Egypt, supporters of Ayyubid legitimacy rallied around al-Nasir Yusuf (1236–1260), the grandson of al-Adil and ruler of Damascus and Syria. His failed attempt to invade Egypt in 1251 was overshadowed by the threat of the Mongols from the east, who destroyed Baghdad (1258), invaded Syria (1259), and captured and brutally sacked Aleppo, and conquered Damascus (1260). Al-Nasir was captured and put to death along with most surviving Ayyubid princes in Syria. The Mamluk victory over the Mongols at the battle of Ayn Jalut (1260) allowed them to add most of Palestine and Syria to their new sultanate.

WILLIAM J. HAMBLIN

See also: Egypt: Fatimids, Later; Salah al-Din/Saladin.

Further Reading

Daly, M.W., and Carl F. Petry, eds. The Cambridge History of Egypt. Vol. 1, Islamic Egypt, 640– 1517. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Gibb, H.A.R., et al. eds. The Encyclopedia of Islam. 11 vols. Leiden: Brill, 1960–2002.

Humphreys, R.S. From Saladin to the Mongols: The Ayyubids of Damascus. Syracuse: State University of New York Press, 1977.

Ibn al-Furat. Ayyubids, Mamlukes and Crusaders. Translated By U. and M.C. Lyons. Cambridge: Heffer, 1971.

Lev, Y. Saladin in Egypt. Leiden: Brill, 1999.

Maqrizi. A History of the Ayyubid Sultans of Egypt. Translated by R.J.C. Broadhurst. Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1980.

Lyons, M.C., and D.E.P. Jackson. Saladin: The Politics of the Holy War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982.

Setton, K.M., ed. A History of the Crusades. 6 vols. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1969–1989.

Vermeulen, U., and D.de Smet, eds. Egypt and Syria in the Fatimid, Ayyubid and Mamluk Eras. 3 vols. Leuven: Uitgeverij Peeters, 1995–2001.

Egypt and Africa: 1000–1500

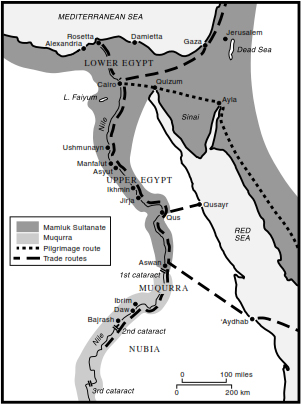

From Egypt, Islamic influence extended in three directions: Through the Red Sea to the eastern coastal areas, up the Nile Valley to the Sudan, and across the western desert to the Maghrib.

The Arab conquest, and the southward expansion of Islam from Egypt, were arrested by the resistance of the Christian kingdoms of Nubia. By the tenth century, however, a peaceful process of Arabization and Islamization was going on in northern Nubia as a result of the penetration of Arab nomads. Muslim merchants settled in the capitals of the central and southern Nubian kingdoms, al-Maqurra, and ‘Alwa. They supplied slaves, ivory, and ostrich feathers to Egypt. From the eleventh century, a local Arab dynasty, Banu Kanz, ruled the Nubian-Egyptian border. For four centuries they served both as mediators between Egyptian and Nubian rulers and as proponents of Egyptian influence in Nubia. By the beginning of the fourteenth century, they assumed control of the throne of Nubia after they had married into the Nubian royal family.

Arab revolts in Upper Egypt were endemic during the Fatimid and Ayyubid periods. The trained Mamluk troops defeated the Arab tribes that were forced to move southward, thus intensifying the process of Arabization of Nubia. Since the second half of the thirteenth century the Mamluk sultans had frequently intervened in the internal affairs of the Nubian kingdoms, and gradually reduced them to the status of vassals. In 1315 the Mamluks installed as king a prince who had already converted to Islam. This was followed two years later by the conversion of the cathedral of Dongola into a mosque. The Christian kingdom became practically a Muslim state. Christianity lingered on until the beginning of the sixteenth century.

Once the barrier formed by the Nubian kingdoms had been broken, waves of Arab nomads coming from Upper Egypt pushed beyond the cataracts, and spread westward into the more open lands of Kordofan and Darfur, and as far as Lake Chad. In 1391 the king (mai) of Bornu, ‘Uthman ibn Idris, wrote to Barquq, the Mamluk sultan of Egypt, concerning harassment by Arab nomads, who captured slaves including the king's own relatives. These slaves were sold to Egyptian merchants, and the king of Bornu asked the sultan to return the enslaved people.

With the decline of Christianity in Nubia, Ethiopia remained the only Christian power in Africa. There were close contacts between Ethiopia and Egypt throughout the Mamluk period. There was some awareness of the fact that the Ethiopians controlled the sources of the Blue Nile. The Ethiopians were concerned with the fate of the Christian Copts in Egypt, and when in the middle of the fourteenth century the Patriarch of Alexandria was arrested the Ethiopians retaliated by seizing all Muslims in their country and drove away all the Egyptian caravans. The Mamluks released the patriarch, and trade was resumed.

Beginning in the Fatimid period in the tenth century, Egypt developed trade with the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean. Muslim seamen from Egypt and Arabia established commercial centers along the Red Sea and Africa's east coast. Ivory and spices were exported via Egypt to the Mediterranean trading cities. Ethiopian slaves were in great demand in all Muslim countries. In the fourteenth century Egyptian economic influence was paramount in Zeila and other ports which were the starting points for trade routes to the interior. Muslim principalities emerged on the fringes of Christian Ethiopia, and the Egyptian rulers sought to be their protectors. Students from southern Ethiopia had their own hostel in al-Azhar. The Egyptians did not venture beyond Zeila, and there is no evidence for direct contacts between Egypt with the rest of the Horn of Africa and East Africa. Still, the role of Egypt in the development of Muslim trade all over the Indian Ocean must have indirectly influenced also the rise of Muslim trading towns on the East African coast. At the end of the period surveyed in this article the Portuguese entered the Indian Ocean and broke the monopoly of Egypt as the commercial intermediary between the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean.

Between the tenth and the sixteenth centuries Egypt absorbed huge numbers of black slaves from various parts of Africa, mainly from Nubia and Ethiopia. During the Mamluk period there were also slaves from central and western Africa. Black eunuchs in the service of the Mamluks were exported to Egypt from West Africa. Nupe (in present-day Nigeria) might have been the site where eunuchs were castrated.

According to Ibn al-Faqih (writing shortly after 903), there was a busy route connecting the Egyptian oases of the Western Desert with Ghana. But, according to Ibn Hawqal (writing between 967 and 988), this route was abandoned during the reign of Ibn Tulun (868–884) “because of what happened to the caravans in several years when the winds overwhelmed them with sand and more than one caravan perished.”

In the middle of the thirteenth century, a hostel was founded in Cairo for religious students from Kanem. In the second half of the thirteenth century, two kings of Mali visited Cairo on their way to Mecca. But the most famous pilgrim-king was Mansa Musa, whose visit to Cairo in 1324 left such an impression in Egypt that all Egyptian chronicles, as late as the middle of the fifteenth century, recorded the event. The huge quantities of gold that he spent affected the exchange rate between gold and silver.

After the exhaustion of the Nubian gold mines of al-’Allaqi, Mamluk coins were minted from West African gold. According to al-’Umari (writing in 1337), the route from Egypt to Mali once again “passed by way of the oases through desert country inhabited by Arab then by Berber communities.” Early in the sixteenth century, Leo Africanus said that the people of the Egyptian oases were wealthy because of their trade with the Sudan. Another route passed through Takedda and Gao. Egyptian merchants visited the capital of Mali, and some of them bought from a profligate king of Mali, Mari Jata II (1360– 1373), a boulder of gold weighing twenty qintars. In return for gold, Mali was a market for Egyptian goods, particularly fabrics. Mamluk brass vessels found in the Brong region, north of Asante, are silent witnesses to the trade with Egypt. The flow of gold to Egypt diminished somewhat in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries because of competition by Italian merchants in the North African coast, who channeled the gold to the Italian cities that were hungry for gold.

In the second half of the fifteenth century, the growth and refinement of scholarship in Timbuktu may largely be explained by influence from Cairo, then the greatest Muslim metropolis. Scholars of Timbuktu, on their way to Mecca, stayed for some time in Cairo, and studied with its distinguished scholars and Sufis. The Egyptian scholar who had the greatest influence in West Africa was Jalal al-Din al-Suyuti (1445–1505). In his autobiography al-Suyuti boasted about his fame in West Africa. Indeed, his Tafsir is still the most widespread Koranic exegesis in this part of the world. He corresponded with West African rulers and scholars.

In 1492 Askiya Muhammad led a religiopolitical revolution in Songhay that made Islam the cornerstone of the kingdom. Four year later, in 1496–1497, Askiya Muhammad visited Cairo on the way to Mecca. In Cairo he met Jalal al-Din al-Suyuti, from whom he learned “what is permitted and what is forbidden.” It was probably al-Suyuti who introduced Askiya Muhammad to the ‘Abbasid Caliph, who lived in Cairo under the patronage of the Mamluk sultans. The ‘Abbasid Caliph delegated authority to Askiya Muhammad that gave legitimacy to his rule. Twelve years earlier, in 1484, al-Suyuti was instrumental in arranging a similar investiture by the ‘Abbasid Caliph to the king of Bornu ‘Ali Gaji (1465–1497).

Al-Suyuti's teaching mitigated the uncompromising zeal of the North African radical al-Maghili, who sought to become the mentor of Sudanic kings at that time. Al-Suyuti saw no harm in the manufacture of amulets and ruled that it was permissible to keep company with unbelievers when no jizya was imposed on them. Al-Suyuti's pragmatic approach, representing the conservative tendencies of the alliance of scholars, merchants, and officials in Mamluk Egypt, contributed to the elaboration of an accommodating brand of Islam in Timbuktu of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

NEHEMIA LEVTZION

Further Reading

Hasan, Y.F. The Arabs and the Sudan. Edinburgh: 1967.

Hrbek, I. “Egypt, Nubia and the Eastern Deserts.” The Cambridge History of Africa. Vol. 3 (1977): 10–97.

Levtzion, N., and J.F.P. Hopkins. Corpus of Early Arabic sources for West African History. Princeton, N.J. 2000.

Levtzion, N. “Mamluk Egypt and Takrur (West Africa).” In Islam in West Africa. Aldershot: 1994.

Sartain, E.M. “Jalal al-Din al-Suyuti's Relations with the People of Takrur.” Journal of Semitic Studies (1971): 193–198.

Egypt: Mamluk Dynasty: Baybars, Qalawun, Mongols, 1250–1300

The Mamluk dynasty rose to power in Egypt through a series of crises forced upon the Ayyubid dynasty by exterior threats. The Mamluks themselves were slaves purchased in large quantities by Sultan al-Salih Ayyub (r. 1240–1249), who were then trained as soldiers, converted to Islam, and then manumitted. The Mamluks formed an elite corps of soldiers with loyalty only to their former master. With the Mongol invasions of the Kipchak steppe, in what is now Russia, large numbers of Turks were readily available.

Egypt under the Mamluks, c. 1250–1500.

The first exterior threat that led to the rise of the Mamluks was the Seventh Crusade led by King Louis IX (1226–1270) of France in 1249. As the army of King Louis invaded Egypt, al-Salih Ayyub died. His son, al-Mu'azzam Turan-shah (r. 1249–1250) was not immediately present, and the Ayyubids of Egypt were briefly without leadership. Meanwhile, King Louis's army had halted at the fortified city of Mansurah. His vanguard swept away all opposition and entered the city before becoming trapped and annihilated by the defenders led by the Bahriyya regiment of al-Salih's Mamluks. The Muslim forces led by the Mamluks soon surrounded the Crusaders and King Louis. Facing the potential annihilation of his disease-ridden army, King Louis surrendered.

Upon victory, Sultan Turan-shah arrived and became the ruler of Egypt in 1249. The Bahriyya Mamluks, along with other Mamluks desired more power in the government due to their efforts at Mansurah. Turan-shah, however, disagreed and only placed his own Mamluks in positions of powers, thus alienating his father's Mamluks. In retaliation, Rukn al-Din Baybars, who also led troops at Mansurah, and other Mamluk leaders staged a coup and assassinated Turanshah in 1250, three weeks after the victory at Mansurah.

The Mamluks then elevated al-Mu'izz Aybak al-Turkmani (1250–1257) to the throne. During the reign of Aybak, a power struggle between the Bahriyya and other regiments ensued, resulting in the flight of most of the Bahriyya to Syria and to Rum (modern Turkey). After Shajar al-Durr, Aybak's queen, assassinated him in 1257, the victorious faction, the Mu'izziyya led by Kutuz, elevated Aybak's son, al-Mansur ‘Ali (1257–1259) to the throne though he was only fifteen. Nevertheless, he served as a figurehead while the Mamluk leaders waged their own power struggles behind the throne.

The second crisis that led to the firm establishment of the Mamluk dynasty was the invasion of the Mongols. After destroying the Abbasid Caliphate based in Baghdad in 1258, the Mongol armies led by Hulegu (d. 1265), a grandson of Chinggis Khan (1162– 1227) marched into Syria, capturing Aleppo and Damascus with relative ease by 1260. There was little reason to think that the Mongols would not also invade Egypt after they consolidated their Syrian territories.

Their arrival prompted a change in policy among the Mamluks. Sultan al-Mansur ‘Ali's reign came to an end as al-Muzaffar Kutuz (1259–1260) became the ruler under the rationale that it was better to have a seasoned warrior rather than a child. In addition, the Bahriyya regiment led by Baybars came back to Egypt to join the Mamluk army against the Mongols. After executing the Mongol envoys, Kutuz decided to go on the offensive rather than await the Mongol advance. His decision was well-timed as the bulk of Hulegu's army had withdrawn from Syria, and only a small force remained under the Mongol general Ket-Buqa, whom Kutuz and Baybars defeated at the battle of ‘Ayn Jalut.

Kutuz's glory was short-lived, however, as Baybars staged a coup against him during their return to Syria. Rukn al-Din Baybars Bunduqari (1260–1277) thus was elevated to the Mamluk throne of a kingdom that now consisted of Egypt and Syria. Baybars immediately began to secure his throne by moving against the Ayyubid princes of Syria as well as dealing with any dissenting Mamluk factions. Furthermore, although the Mongol Empire dissolved into four separate empires and became embroiled in a civil war, the Mongol Il-Khanate of Iran and Iraq remained a very dangerous foe.

To counter this, Baybars arranged an alliance with the so-called Mongol Golden Horde, which dominated the Russian lands to the North, who also fought the Il-Khanate. In addition, Baybars focused his offensive campaigns against the Mongols allies in Cilicia or Lesser Armenia and against the Crusader lord, Bohemund of Antioch (1252– 1275) and Tripoli. Baybars's invasions of their territories effectively neutralized them as a threat.

Not all of the Crusaders allied with the Mongols, as did Bohemund. Initially, Baybars left these in peace while he dealt with more urgent threats. He, however, was very active in ensuring their downfall. Through diplomatic efforts, he was able to divert another Crusade led by King Louis IX to Tunis with the help of Charles D'Anjou, the king's own brother. Charles D'Anjou enjoyed profitable commercial and diplomatic relations with Egypt and did not want to dampen them with an invasion. Without the assistance of another Crusade, those Crusaders who remained in Palestine could only defend their territories. Baybars quickly relieved them of a number of strongholds including Crac des Chevaliers, Antioch, Caesarea, Haifa, Arsuf, and Safad. He also crowned his military career with a second defeat of the Mongols at Elbistan in 1277.

The Sultan Barquq complex was built in 1384 by the first tower or Burgi Mameluke sultan who ruled from 1382 until 1399. This complex includes a cruciform medersa; a khanqa, which offered living quarters for the Sufi mystics; and a tomb of one of the sultan's daughters. Cairo. © Mich. Schwerberger/Das Fotoarchiv.

Baybars died in 1277. His military success was due to not only generalship but also to his use of diplomacy to gain allies, which in turn prevented the Mongols of Iran from focusing their efforts on him. Much of Baybars’ reign focused on securing Syria from the Mongols, which led to his efforts against the Crusader states, and Cilicia. Furthermore, in Egypt he solidified the power of the Mamluks, allowing their rule to continue after his death.

Baybars's son and successor, al-Malik al-Sa'id Muhammad Barka Khan (1277–1279), however, did not have the opportunity to equal his father's deeds. Although appointed as joint sultan in 1266, and secretly elevated to power on his father's deathbed, another coup soon developed in which another Mamluk emir named Qalawun committed regicide, as had the previous rulers, and soon rose to the throne in 1279.

To secure his power, Qalawun (1279–1290) purged the al-Zahirriya, or Baybars’ own Mamluks. He then quelled any internal revolt. Qalawun, like Baybars, however, still had to contend with the Mongols. Abaqa (1265–1282), the ruler of the Il-Khanate of Persia sent another army into Syria in 1281. This force, however, met a similar fate as those before it. Qalawun's army emerged victorious and routed the Mongols.

This victory allowed Qalawun to turn his attention against the remaining Crusaders. Through diplomacy and force, Qalawun steadily reduced the Crusader castles one by one. By 1290 only Acre and few minor castles remained in the hands of the Crusaders. Though he laid siege to Acre, Qalawun would not see the fall of this remaining stronghold, as he died in 1290.

Qalawun, however, was somewhat more successful than Baybars at establishing a hereditary succession. His son, al-Ashraf Khalil (1290–1293) continued the siege and captured Acre in 1291. This victory allowed him to firmly establish himself on the throne. After this, al-Ashraf swept away the remaining Crusader footholds and ended their two hundred year presence in Palestine.

Regicide, however, was an ever-present threat in the Mamluk sultanate. When alAshraf attempted to replace the Turk-dominated Mamluk corps with Circassian recruits, the Mamluks rebelled again. Qalawun had actually initiated the introduction of Circassians, but al-Ashraf's continuation of it and arrogance prompted another rebellion. Though al-Ashraf Khalil died under the sword in 1293, his Mamluks, known as the Burjiyya, successfully gained control of Cairo and the sultanate allowing the Qalawunid dynasty to continue in name, if not in actual power.

The uncertainty of the Mamluks’ legitimacy as rulers that surrounded the Mamluk kingdom and the threat of the Mongols in the Middle East hampered the Mamluks’ interests in Africa. Trade with North and Sub-Saharan Africa remained a constant. Furthermore, the Mamluks did maintain and stabilize their rule in southern Egypt by quelling the Beduin tribes. As the threat from the Mongols and Crusaders diminished, the Mamluks began to become more involved with other powers to the south and west.

TIMOTHY MAY

Further Reading

Amitai-Preiss, R. “In the Aftermath of ‘Ayn Jalüt: The Beginnings of the Mamlük-Ilkhänid Cold War.” Al-Masäq 3 (1990): 1–21.

Ayalon, D. Outsiders in the Lands of Islam. London: Variorum Reprints, 1988.

Holt, P.M. The Age of the Crusades: The Near East from the Eleventh Century to 1517. London: Longman, 1986.

——. Early Mamluk Diplomacy (1260–1290): Treaties with Baybars and Qalâwûn with Christian Rulers. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1995.

Humphreys, R. Stephen. From Saladin to the Mongols: The Ayyubids of Damascus, 1193 to 1260. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1977.

Egypt: Mamluk Dynasty (1250–1517): Literature

Literary production during the Mamluk Sultanate was massive in scope. Authors from divers backgrounds produced works across the gamut of genres and in different languages, supported in part by the patronage of the Mamluk elite. While much of the literary output of any medieval Muslim society defies easy categorization into the genres or modern literary analysis, the Mamluk era is known today for its works of poetry, history, and for what may be called, popular entertainment.

Arabic poetry was produced in vast quantities, although the diwans (collected verses) of many poets remain unedited. Thus our knowledge of this key aspect of Mamluk literary culture remains spotty and uneven in coverage. Classical poetical types such as fakhr (self-praise), ghazal (love poetry), hamasah (personal bravery), hija’ (invective), madih (panegyric), ritha’ (elegy), and wasf (descriptive) were all well represented as well as less traditional styles such as the highly rhetorical badi’ and the colloquial verse known as zajal. Interest in Mamluk poetry, however, has often been affected by later aesthetic trends. Techniques such as tawriyah (forms of word-play resembling double entendre), for example, were quite common in Mamluk poetry.

The popularity of ornamentation and literary devices among Mamluk-era poets no doubt contributed to their being classified by earlier Western scholars as “merely elegant and accomplished artists, playing brilliantly with words and phrases, but doing little else” (Nicholson 1969, pp.448–450). Some modern Arab literary critics, meanwhile, dismiss this poetry as “decadent, pallid, worn out, and lacking authenticity” (Homerin 1997, p.71). These views, while still encountered, are under increasing challenge by recent scholars who approach the material on its own terms as well as viewing Mamluk poetry as a vast and rich source for the study of Mamluk-era life and culture.

Major poets include al-Ashraf al-Ansari (d.1264); Al-Afif al-Tilimsani (d.1291) and his son, known as al-Shabb al-Zarif (d.1289); al-Busiri (d.1295), well-known for his ode to the Prophet; Safi al-Din al-Hilli (d. 1349); Ibn Nubatah al-Misri (d.1366), particularly well-known for his use of tawriyah; Ibn Abi Hajalah (d.1375); Ibn Makanis (d.1392); Ibn Malik al-Hamawi (d.1516); and the female poet ‘A'ishah al-Ba'uniyah (d.1516). While technically an Ayyubid-era poet, the work of ‘Umar Ibn al-Farid (d.1235) was well known and extensively cited after his death, and should be mentioned as representing the blending of poetry with mystical (sufi) concerns.

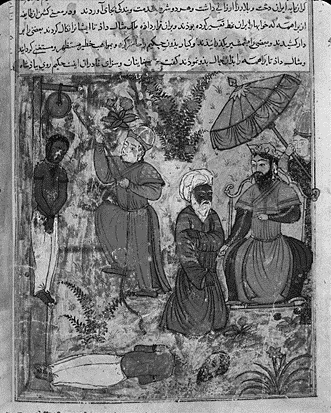

The sultan rendering justice. Miniature from The Fables of Bidpai: The Book of Kalila and Dimna (Arabic translation of the Panca-Tantra), fol. 100. Fourteenth century. National Library Cairo. Anonymous. © Giraudon/Art Resource, New York.

The Mamluk age is commonly celebrated for its prolific production of historical works. The major cities of the Mamluk sultanate were centers of learning and commerce, and in no small part the revenues of the latter supported the producers of the former. As a result, the Mamluk era is well recorded in many contemporary chronicles, regnal histories, celebrations of cities and other locales, biographical compilations, and other historically oriented texts. These works are in a variety of styles, ranging from ornate rhymed prose to straightforward narratives containing significant amounts of colloquial language. The authors of these texts were as varied as the texts themselves. Histories were written by Mamluk soldiers, government clerks, and the learned class of the ‘ulama’ (those learned in the Islamic sciences). To cite a minimum of examples, Baybars alMansuri (d.1325) was a Mamluk officer who participated in many of the military events he later discussed in his writings. Al-Maqrizi (d.1442) was a jurist and disappointed civil servant who frequently poured vitriol and criticism on the ruling Mamluk elite in his many works. Ibn Taghri Birdi (d.1470), the son of a major Mamluk amir, wrote histories reflecting the sympathies and insights made possible by his close association with that same ruling elite. Polymaths such as Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani (d.1449) and al-Suyuti (d.1505) produced important historical works as but a small part of their vast oeuvre addressing many topics. Finally, in a similar situation to that of Mamluk poetry mentioned above, many important historical works, such as much of the chronicle of alAyni (d.1451), remain in manuscript form.

While often looked down upon by the literary elite past and present, the Mamluk period produced significant works of what may be termed popular entertainment. Apparently performed or recited in public spaces, these works are increasingly studied for what they tell us about the lives and attitudes of the lower social classes absent from the majority of the Mamluk historical works. In particular, the texts of three shadow plays by Ibn Danyal (d.1311), otherwise known as a serious poet, have survived. They are populated with a rogues’ list of characters and while clearly works created for entertainment, give a glimpse of the seamier side of Mamluk Cairo as it was perceived by their author.

Much more well known are the tales known by the title Alf Layla wa Layla, commonly rendered as the “Thousand and One Nights,” or “the Arabian Nights Entertainments” (or some combination thereof). These stories, ranging from a few paragraphs to hundreds of pages in length, are far from the collection of sanitized and selective children's stories with which many modern readers are familiar. They are a complex conglomeration of many tales that likely took an early shape among the professional storytellers of the Mamluk domains. As Muhsin Mahdi has shown, the earliest known manuscript of the Nights dates from late Mamluk Syria. It contains both the famous frame-story of the cuckolded and murderous King Shahriyar as well as the first thirty-five stories told by his latest wife and potential victim Sheherezade to postpone his deadly intentions. While some of the stories are clearly of earlier origin, and many are set in the golden past of the Abbasid Baghdad of Harun al-Rashid, descriptive details in many of these thirty-five tales and the later accretions reveal their Mamluk context. Their potential for providing insights into Mamluk-era life has been demonstrated by Robert Irwin.

WARREN C. SCHULTZ

Further Reading

Guo, L. “Mamluk Historiographic Studies: The State of the Art,” Mamluk Studies Review 1 (1997): 15–43.

Homerin, Th. Emil, ed. Mamluk Studies Review.

Homerin, Th. Emil, ed., “Reflections on Poetry in the Mamluk Age,” Mamluk Studies Review 1 (1997): 63–86.

——. Mamluk Studies Review. 8 (2003).

Irwin, R. The Arabian Nights: A Companion. London: Allen Lane/Penguin, 1994.

Kahle, P. Three Shadow Plays by Muhammad Ibn Danyal E.J. W. Gibb Memorial, n.s. 32. Cambridge: Trustees of E.J.W. Gibb Memorial, 1992

Little, D.P. “Historiography of the Ayyubid and Mamluk epochs.” In The Cambridge History of Egypt. Vol. 1. Edited by Carl F. Petry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Mahdi, M. The Thousand and One Nights. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1995.

Meisami, J.S., and Paul Starkey, eds. Encyclopedia of Arabic Literature. New York: Routledge, 1998.

Nicholson, R.A. A Literary History of the Arabs. Reprint. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1969.

Egypt: Mamluk Dynasty (1250–1517): Army and Iqta’ System

Although the phenomenon of using slaves as soldiers had antecedents in pre-Islamic and early Islamic times, the formal institution of military slavery in the Islamic world had its origin in the Abbasid caliphate in the ninth century, when al-Mu'tasim (833–842), distrusting the loyalty of some regiments of his army, came increasingly to rely on his personal slaves for protection, eventually expanding his slave bodyguard to an alleged 20,000 men, garrisoned at Samarra. From the ninth through the eighteenth centuries the Mamluk soldierslave corps formed an important part of the armies of many Islamic dynasties, including the famous Janissaries of the Ottoman sultans. It was in Egypt, however that the mamluk military system reached it apogee, under the Mamluk Sultanate (1250–1517), when Egypt was ruled for a quarter of a millennia by an aristocracy of slave-soldiers.

Mamluk is an Arabic term meaning “possessed” or “owned,” and generally refers to military slavery. (Military slaves were also sometimes called ‘abd or ghulam.) During the Mamluk dynasty the major source of recruitment was Turkish nomads from the steppes of Central Asia, who were viewed as exceptionally hardy, loyal and warlike, and who had learned basic skills of archery and horsemanship during their nomadic youth on the steppe. During the early Mamluk dynasty the majority of the mamluks came from Kipchak tribes; after the reign of Sultan Barquq (1382–1399), recruitment focused on Circassians. However, during different periods of the dynasty, smaller numbers of Mamluks were recruited from a number of additional ethnic groups, including Mongols, Tatars, Byzantines, Russians, Western Europeans, Africans, and Armenians.

Mamluks began their military careers as young nomad boys on the steppes of Central Asia, who were captured as slaves during military campaigns or raids. Slave merchants would select boys in their early teens with the proper physique and skills, transporting them to the slave markets of Syria or Egypt. There, agents of the sultan would purchase the most promising candidates, enrolling them in a rigorous training program. The new Mamluk recruits were taught Islam, and at least nominally converted, while engaging in multiyear military training focusing on horsemanship, archery, fencing, the use of the lance, mace and battleaxe, and many other aspects of military technology, tactics and strategy; several dozen military manuals survive detailing all aspects of Mamluk military science and training. Emphasis was placed on skill at mounted archery; Mamluk warriors represented an amalgamation of long-established Islamic military systems with a professionalized version of the warrior traditions of steppe nomads.

The displaced young teenagers soon became fiercely loyal to their new surrogate families, with the sultan as their new father and their barracks companions as their new brothers. They came to realize that, despite their technical slave-status, the Mamluk military system provided them a path to wealth, power, and honor, and, for the most fortunate and bold, even the sultanate itself. Upon completion of the training program, which lasted around half a dozen years, young Mamluk cadets were manumitted and began service in the army, the brightest prospects being enlisted in the Khassikiyya, the personal bodyguard of the sultan. Mamluks were distinguished from the rest of society by ranks, titles, wealth, dress, weapons, horse riding, special position in processions, and court ritual—they were renowned for their overweening pride in their Mamluk status. The Mamluks thus formed a military aristocracy, which, ironically, could only be entered through enslavement.

Armies were organized into regiments often named after the sultan who had recruited and trained them—for example, the Mamluks of the sultan al-Malik al-Zahir Baybars (1260–1277) were the Zahiriyya. Successful soldiers could be promoted from the ranks. The Mamluk officer corps was divided into three major ranks: Amir (“commander”) of Ten (who commanded a squad of ten Mamluks), the Amir of Forty, and the highest rank, “Amir of One Hundred and Leader of One Thousand,” who commanded one hundred personal Mamluks, and lead a 1000-man regiment in combat. There were traditionally twenty-four Amirs of One Hundred, the pinnacle of the Mamluk army, who formed an informal governing council for the sultanate; some eventually became sultan.

The Mamluks had a formal and highly organized system of payment based on rank and function, overseen by a sophisticated bureaucracy. Remuneration included monthly salaries, equipment and clothing, food and fodder supplies, and special combat pay. Many Mamluk officers and soldiers were given land grants known as iqta’, both for their own support and to pay for the maintenance of additional soldiers under their command. Such grants were carefully controlled and monitored by the bureaucracy, and amounted to regular payment of revenues and produce of the land rather than a permanent transfer of ownership; the grant of an iqta’ could be withdrawn and redistributed.

At its height, the Mamluk military system was one of the finest in the world, with the Mamluks of Egypt simultaneously defeating both the Crusaders and the Mongols in the second half of the thirteenth century. During most of the fourteenth century, however, the Mamluks faced no serious outside military threat, and their military training and efficiency began to decline. During this period the major fighting the Mamluks engaged in was usually factional feuding and civil wars associated with internal power struggles and coups. When faced with the rising military threat of the Ottoman Turks in the late fifteenth century, the Mamluks initiated military reforms, which ultimately proved insufficient. The Mamluks were also unsuccessful at efficiently integrating new gunpowder weapons into a military system dominated by a haughty mounted military aristocracy. The Mamluks were decisively defeated in wars with the rising Ottomans (1485–1491, 1516–1517), who conquered Egypt in 1517, overthrowing the Mamluk sultanate.

WILLIAM J. HAMBLIN

Further Reading

Amitai-Preiss, R. Mongols and Mamluks: The Mamluk-Ilkhanid War, 1260–1281. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Ayalon, D. The Mamluk Military Society. London: Variorum Reprints, 1979.

Ayalon, D. Studies on the Mamluks of Egypt (1250–1517). London: Variorum, 1977.

Ayalon, David. Islam and the Abode of War: Military Slaves and Islamic Adversaries, (Aldershot, Great Britain; Brookfield, Vt.: Variorum, 1994).

Ayalon, D. Gunpowder and Firearms in the Mamluk Kingdom: A Challenge to Mediaeval Society, 2nd ed. London and Totowa, N.J.: F. Cass, 1978.

Gibb, H.A.R., et al., eds. The Encyclopedia of Islam, 11 vols. Leiden: Brill, 1960–2002.

Har-El, S. Struggle for Domination in the Middle East: The Ottoman-Mamluk War, 1485–1491. Leiden: Brill, 1995.

Holt, P.M. The Age of the Crusades: The Near East from the Eleventh Century to 1517. New York: Longman, 1986.

Irwin, R. The Middle East in the Middle Ages: The Early Mamluk Sultanate 1250–1382. London: Croom Helm/Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1986.

Nicolle, D. The Mamluks 1250–1517. London: Osprey, 1993.

Petry, C.F. Protectors or Praetorians ?: The Last Mamluk Sultans and Egypt's Waning As a Great Power. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1994.

Petry, C.F. Twilight of Majesty: The Reigns of Mamluk Sultans Al-Ashraf Qaytbay and Qansuh alGhawri in Egypt. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1993.

Pipes D. Slave Soldiers and Islam: The Genesis of a Military System. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981.

Daly, M.W. and C.F. Petry. eds. The Cambridge History of Egypt, Vol. 1: Islamic Egypt, 640–1517, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Egypt: Mamluk Dynasty (1250–1517): Plague

In the middle of the fourteenth century a destructive plague swept through Asia, North Africa, and Europe, devastating nations and causing serious demographic decline. Cities and buildings were laid waste, roads and way signs were obliterated, settlements and mansions became empty, dynasties and tribes grew weak. The entire inhabited world changed.

Thus wrote Ibn Khaldun in his Muqaddimah (v.1, p.64). The famous North African scholar spent the last decades of his life in Mamluk Cairo and saw firsthand the effects the early occurrences of the plague had on the lands and people of the Mamluk Sultanate.

The phrase “Black Death” was not used in the medieval Islamic world. In the Mamluk sources, the devastating and recurring pandemics were usually referred to by the common Arabic nouns ta'un (plague) or waba’ (pestilence). From the initial outbreak of 1347– 1349 to the end of the Mamluk Sultanate in 1517, there were approximately twenty major epidemics that affected large areas of Mamluk Egypt, occurring about every eight to nine years. Mamluk Syria seemed to be slightly less afflicted, with only eighteen epidemics over the same period. Given the descriptions of symptoms and the general mortality reported, it seems clear that the disease was that linked to the plague bacilli Pasteurella pestis or an earlier variant thereof. Buboes, for example, were frequently referred to as “cucumbers” (khiyar) in the sources. Michael Dols has argued convincingly that during several of the outbreaks a total of three forms of the disease—the pneumonic, bubonic, and septicaemic—struck simultaneously. The outbreak of 1429–1430, for example, was especially severe and was called in some sources the “great extinction.” The accompanying epizootics among animals frequently mentioned suggests a variant form, or perhaps an accompanying and as yet undetermined agent.

While demography for this period is inexact, it seems probable that the population of Egypt suffered a prolonged and aggregate decline of approximately one-third or so by the beginning of the fifteenth century. Egypt's population remained at levels lower than its pre-plague years into the Ottoman period. The plague did not afflict all segments of society equally. Reflecting the bias of the sources, we know more about the impact on the cities of Egypt then we do on the rural areas. It is common to encounter statements like the following in the chronicles: “the plague caused death among the Mamluks, children, black slaves, slave-girls, and foreigners” (Ayalon, p.70). The evidence suggests that the Royal Mamluks were especially hard hit, perhaps due to their recent arrival in Egypt, and previous lack of exposure to the plague. The cost of replacing these expensive recruits no doubt contributed to the increasing economic strain on the Mamluk regime during the fifteenth century.

The recurrent nature of the pandemic had other negative repercussions on the regime. While there is no evidence for a complete breakdown of either government or religious administrations, we read of confusion and disruption in land-holding, tax-collecting, military endeavors, the processing of inheritances, and the filling of vacated offices, not to mention the looting of abandoned properties and other civil unrest. Economic ramifications took the shape of price disruptions, labor shortages, decreased agricultural production in both crops and livestock, and an overall decline in commerce. Many modern scholars argue that the demographic decline brought about by the plague is the main contributing factor to the economic difficulties of the fifteenth century, and that the policies adopted by the Mamluk regime in that century are best understood as reactions to, not causes of, that decline.

Normative societal reaction to the plague was shaped by the ‘ulama’, those learned in Islamic knowledge. The guidance provided by this communal leadership was shaped primarily by those Hadiths of the prophet Muhammad related to disease epidemics, and featured these main points. First, the plague was both a mercy and a martyrdom for the believer, but a punishment for the unbeliever. Second, a Muslim should neither flee nor enter a plague-stricken region. And third, there was no interhuman transmissibility of the disease; it came directly from God (medieval Arabic medical terminology did not distinguish between contagion and infection). Other reactions on the part of the populace were condemned as innovation. The recurrent stressing of these points in the numerous pestschriften that survive, along with contrary reports in the chronicles, would seem to indicate that these policies were not always followed to the letter.

Nevertheless, it is clear that religion shaped both the individual and communal response to the horror and unpredictability of the plague, as seen in the poignant passage by the Mamluk-era author Ibn al-Wardi, who died in 1349, during the latter stages of the first outbreak:

I take refuge in God from the yoke of the plague. Its high explosion has burst into all countries and was an examiner of astonishing things. Its sudden attacks perplex the people. The plague chases the screaming without pity and does not accept a treasure for ransom. Its engine is far-reaching. The plague enters into the house and swears it will not leave except with all of its inhabitants. “I have an order from the qadi (religious judge) to arrest all those in the house.” Among the benefits of this order is the removal of one's hopes and the improvement of his earthly works. It awakens men from their indifference for the provisioning of their final journey. (Dols 1974, p.454)

WARREN C. SCHULT

See also: Ibn Khaldun: Civilization of the Maghrib.

Further Reading

Ayalon, D. “The Plague and Its Effects upon the Mamluk Army.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society (1946): 67–73.

Dols, M.W. “Al-Manbiji's ‘Report of the Plague’: A Treatise on the Plague of 764–65/1362–64. In The Black Death: The Impact of the Fourteenth-Century Plague, edited by Daniel Williman. New York: Center for Medieval and Early Renaissance Studies, 1982.

Dols, M.W. The Black Death in the Middle East. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1977.

Dols, M.W. “The Comparative Communal Responses to the Black Death in Muslim and Christian Societies.” Viator: Medieval and Renaissance Studies 5 (1974): 269–287.

Dols, M.W. “The General Mortality of the Black Death in the Mamluk Empire.” In The Islamic Middle East, 700–1900, edited by A.L. Udovitch. Princeton: Darwin, 1981.

Dols, M.W. “Ibn al-Wardi's Risalah al-Naba’ ‘an al-Waba’, A Translation of a Major Source for the History of the Black Death in the Middle East.” In Near Eastern Numismatics, Iconography, Epigraphy and History: Studies in Honor of George C. Miles, edited by Dickran K. Kouymjian. Beirut: American University Press, 1974.

Dols, M.W. “The Second Plague Pandemic and Its Recurrances in the Middle East: 1347–1894.” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 22 (1979): 162–189.

Ibn Khaldun. The Muqaddimah. Translated by Franz Rosenthal. 3 vols. London: 1958.

Egypt: Ottoman, 1517–1798: Historical Outline

In January 1517 the mamluk sultan of Egypt, Tumanbay, was defeated by the Ottoman sultan Selim I. The Ottoman conquest ended a sultanate that had ruled independent Egypt since 1250. The Ottomans were militarily superior, having cannon and arquebus in the hands of well-organized infantry troops, the Janissaries. The mamluk forces, mostly cavalry, had already been defeated in a battle in Syria. The occupation of Cairo by Selim reduced Egypt to a tributary of the Ottoman Empire, symbolized by the removal of the caliph, the spiritual head of the mamluk sultanate and of the Islamic world, to the imperial capital of Istanbul.

The Ottoman conquest capitalized on rivalries among the mamluks, which had become evident during the Ottoman conquest of mamluk Syria in 1516. By supporting Khayr Bey of Aleppo against his rivals in Cairo, the Ottoman sultan ensured Ottoman supremacy, and in September of 1517 Khayr Bey was appointed the sultan's viceroy in Cairo. The viceroy initially was known by the traditional mamluk title of malik al-umara’, or commander of the princes, as well as residing in the Cairo citadel in a style very much like that of the previous mamluk sultans. Moreover, he reprieved the remaining mamluks, who continued to hold land as a type of feudal assignment, or iqta’, in the twelve administrative districts of Egypt, each of which was headed by a mamluk bey.

Upon the death of Khayr Bey in 1522 the mamluks revolted, resulting in a series of reforms decreed by the Grand Vizier, Ibrahim Pasha, according to the prescriptions of Sultan Sulayman al-Qanuni. Sulayman codified laws for imperial administration across the empire, designed in part to regularize land revenue. In Egypt the reforms ended the system of land assignments and replaced the mamluk assignees with salaried officials, amins. The laws of 1525 established a political constitution that gave Egypt some degree of selfgovernment, specifically through the diwan, or assembly, which contained religious and military notables, such as the agha, or commander of the Janissary troops. The Janissaries were the most important of the seven imperial regiments stationed in Egypt, including another infantry regiment, the Azaban, and two troops of bodyguards or attendants of the viceroy. There were three cavalry units, one of which was composed of mamluks. The mamluks were also given high positions that carried the rank of bey, such as the office of commander of the pilgrimage (amir al-hajj), treasurer (daftardar), command of the annual tribute caravan (hulwan) to Istanbul, and military commands with the rank of sirdar. On the side of the imperial officials, the newly drawn fourteen districts of Egypt were placed under the authority of an Ottoman kashif, who stood above the amins. The formal constitutional structure of 1525 remained intact until the end of the eighteenth century, when Ottoman power in Egypt declined.

Ottoman rule in Egypt depended to a large extent upon maintaining the prestige of the imperial troops. The imperial troops and officers were paid salaries, but the introduction of American silver in the Mediterranean commercial system in the sixteenth century reduced the value of Ottoman currency. The imperial cavalry units revolted against an investigation by the viceroy into Egyptian finances in 1586. This was because the cavalry depended upon illegal taxes to supplement their reduced incomes. In this instance, the troops toppled the viceroy. A second revolt in 1589 resisted a proposed reorganization of the troops. These troubles were followed by an epidemic, and in 1605 the viceroy of Egypt, Ibrahim Pasha, was murdered by his troops. In 1607 the viceroy Muhammad Pasha investigated and suppressed an illegal tax levied by the cavalry. Finally, after a revolt of the imperial troops in 1609, the viceroys turned to the beys whose power was independent of the regiments. As a result, in the seventeenth century the power of the mamluk beys increased in relation to the seven imperial troops.

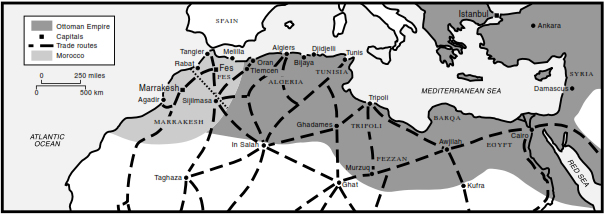

North Africa under the Ottomans, c.1650.

The foremost regiment, the Janissaries, established their power bases in the cities, particularly through influence over commercial wealth, while the mamluk beys invested in landholdings. Personal landholdings were revived with the development of the iltizam system, another form of land assignment that gave the mamluks tax-collecting privileges. The revival of quasi-feudal landholdings undermined the authority of the kashifs, a position that in any case was often given to mamluks beys. Consequently, the mamluks were able to reassert their corporate strength when, in 1631, the beys removed the viceroy, Musa Pasha, and replaced him with a mamluk bey who acted as interim viceroy. This set a precedent recognized by the sultan.

By 1660 the distinction between the constitutional roles of the imperial troops and mamluk beys had become blurred, for instance, a conflict among the leading mamluk factions, the Faqariyya and the Qasimiyya, also involved the Janissary and Azaban troops. At that time the Faqariyya and Janissaries allied and established an ascendance not broken until the great insurrection of 1711. At this point, although the constitutional system remained intact in theory, real power passed to the leading member of the ascendant mamluk faction, the Qazdughliyya, who carried the unofficial title of shaykh al-balad. Through the eighteenth century, individual mamluks built power bases independently of the Ottomans. ‘Ali Bey ruled as shaykh al-balad from 1757 to 1772. He was said to have wanted to revive the mamluk sultanate in Egypt, and challenged the authority of the Ottoman sultan when he invaded Syria in 1770.

Although the viceroys were not effective arbiters of power in Egypt, the Ottoman troops in Egypt had some success in influencing Egyptian politics and economy. Evidently, the Janissaries were integrated into the leading mamluk families through their role as patrons of merchants and artisans. As a result, patronage, rather than formal constitutional procedure, became the usual method of raising revenue and consolidating political power. The decline in the power of the Janissaries in the first half of the eighteenth century is largely the result of their inability to control economic resources, particularly the essential spice and coffee markets. These were undermined by the development of European colonies specializing in their production. By the second half of the eighteenth century Egypt no longer paid an annual tribute to the Ottoman sultan, while ambitious mamluks based their autonomous power on new forms of revenue collection that weighed heavily on the Egyptian population. As a result, at the end of the eighteenth century Egypt was practically independent from the Ottoman Empire, while in political, social, and economic tumult. The period of declining Ottoman power in Egypt, therefore, mirrored events in the rest of the Ottoman Empire, where regional warlords reasserted their autonomy from the middle of the seventeenth century, until Sultan Selim III began modernizing reforms at the end of the eighteenth century.

JAMES WHIDDEN

Further Reading

Ayalon, D. “Studies in al-Jabarti I. Notes on the Transformation of Mamluk Society in Egypt under the Ottomans.” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 3, no. 1 (1960): 275– 325.

Hathaway, J. The Politics of Households in Ottoman Egypt: The Rise of the Qazdaglis. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Holt, P.M. Egypt and the Fertile Crescent, 1516–1922. London: Longman, 1966.

Lane-Poole, S. A History of Egypt in the Middle Ages. London: Methuen, 1901.

Shaw, S.J. The Financial and Administrative Organization and Development of Ottoman Egypt, 1517–1798. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1962.

Winter, M. “Ottoman Egypt.” In The Cambridge History of Egypt, Modern Egypt from 1517 to the End of the Twentieth Century. Vol. 2, edited by M.W. Daly. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Egypt: Ottoman, 1517–1798: Mamluk Beylicate (c.1600–1798)

The beylicate institution revolved around a number of prestigious appointments to the Ottoman government of Egypt. The holders of these appointments held the rank of bey. The most important appointments were command of the pilgrimage, amir al-hajj, and treasurer, daftardar, as well as the distinctive title of shaykh al-balad, which was applied to the bey who had established his political supremacy over his peers. The supremacy of the beylicate was enabled by the formation of mamluk households, led by men who won political power through the military, commerce, or landholding. The households were factions composed of officers, merchants, and other notables, as well as freed slaves (the meaning of the term mamluk). Politics involved contests to control households, the most important being the Faqari, Qasimi and Qazdughli households.

The political role of the households begins in the early seventeenth century, with the rise of the Faqariyya, led by Ridwan Bey al-Faqari. Ridwan Bey succeeded to the office of amir al-hajj when, in 1631, the beys deposed the Ottoman viceroy, Musa Pasha, because he executed one of the bey commanders. From 1640 Ridwan had the support of the Sultan Ibrahim. After 1649 Sultan Mehmed IV and his viceroy Ahmad Pasha attempted to reduce the growing power of the Faqariyya by blocking Ridwan's hold on the command of the pilgrimage. But factional strength was more enduring, and Ridwan held the post until 1656. Yet, upon Ridwan's death, the viceroy gave the command of the pilgrimage to Ahmad Bey, the head of the Qasimiyya household.

The Faqariyya had the support of the Janissaries, who profited from protection money taken from the Cairo merchants. As a result, the Janissary officers were resented by the other imperial troops, and in 1660 the Azaban infantry troop allied with the Qasimiyya against the Janissary officers. The Faqariyya beys fled, and the factional ascendancy passed to the Qasimiyya. Yet, Ahmad was not allowed to attain the autonomous power of Ridwan, and in 1662 he was assassinated by a supporter of the viceroy. Until 1692 the Qasimiyya beys ruled with the support of the Ottoman viceroys, who attempted to bring about some reform to the system of hereditary estates, or iltizams. However, Ottoman reform only tended to divide Egyptian society between urban factions dominated by imperial troops, particularly the Janissaries, and rural society under the control of the mamluks. It was in this period that the iltizam system was firmly entrenched, with the mamluks converting state lands into private domains while the Janissaries converted their control of the custom houses into iltizam hereditary rights in 1671. Thus, in the seventeenth century there was increasing competition between factions for control of resources.

In 1692 the Faqariyya, led by Ibrahim Bey, increased their influence over the Janissaries by winning over the Janissary officer Kucuk Mehmed. But when Kucuk attempted to cancel the Janissary system of protection money in Cairo, he was assassinated by Mustafa Kahya Qazdughli, probably with the support of the Faqariyya faction within the Janissaries. The Faqariyya political and economic dominance lasted until 1711, when an imperial decree against military patronage of economic ventures resulted in another factional war. The “Great Insurrection,” as it was called, pitted the Qasimiyya and the Azabans against the Faqariyya, who were divided. The defeat of the Faqari household also meant the end of Janissary dominance in the cities. Consequently, the authority of imperial troops declined and political power passed to the beys.

After 1711 the preeminence of the beylicate was recognized by the unofficial rank of shaykh al-balad (“lord of the country”). The Qasimiyya head, Isma'il Bey, ruled as shaykh al-balad until 1724 when he was assassinated, as were his two successors. However, during the long rule of Isma'il, the two mamluk households were reconciled. The outcome is evident in the formation of a new household, the followers of alQazdughli. This household rose to prominence by controlling appointments to the Janissaries and Azabans. With the imperial troops now controlled by one household, rivalry between the Azabans and Janissaries was no longer a feature of Egyptian politics. Meanwhile, the Qazdughliyya also placed its followers in the beylicate. As a result the political power of the beylicate became supreme, and the heads of the household alternated holding the posts of amir al-hajj and shaykh al-balad.

In 1754 an insurrection of the Janissaries resulted in the assassination of Ibrahim Kahya Bey, the head of the Qazdughliyya. ‘Ali Bey, a mamluk follower of Ibrahim, became the shaykh al-balad in 1757 and began a period of innovation. He created a personal retinue by elevating his supporters to the beylicate and destroying his factional adversaries. According to the chronicler ‘Abd al-Rahman al-Jabarti, ‘Ali Bey wanted to make himself the sultan of Egypt. Therefore, he created an army of mercenaries with modern firearms. To raise revenue to pay for the army, he imposed extraordinary taxes on the Egyptian peasants, landlords, and merchants. He also confiscated the properties of his rivals. These innovations were accepted by the Ottoman authorities in return for a pledge to pay off the Egyptian deficit to the imperial treasury. Although challenged by opposition groups in Upper Egypt, ‘Ali Bey held power long enough to meet his obligations to the sultan. After these were fulfilled in 1768, he deposed the viceroy and took the office of interim viceroy, qa'im al-maqam. Established as the absolute ruler of Egypt, he turned to conquest, defeating a local warlord in the Hijaz, where he appointed an Egyptian bey as viceroy. In 1771 ‘Ali Bey defeated the Ottoman troops defending Damascus, thus establishing the previous frontiers of the mamluk sultanate.

The innovations of ‘Ali Bey were premature. He could not stand independently of both the Ottomans and the mamluk households. The Ottomans won over one of his closest supporters, Muhammad Bey Abu alDhahab. At the same time, his mamluk rivals who had sought refuge in Upper Egypt, particularly members of the Qasimi faction, allied with the Hawwara, a tribal group in Upper Egypt. Therefore, a combination of factors, but particularly the political rivalries of the beylicate itself, brought about a coalition of forces that defeated ‘Ali Bey in the battle of 1773.

The period from 1773 to 1798 was a time of economic, social and political upheaval, occasioned to a degree by the innovations of ‘Ali Bey. According to the chronicler ‘Abd al-Rahman al-Jabarti, it was a period when the beys practiced expropriation and oppression, levying excessive taxes that ruined cultivation and forced the peasants to take flight. Similarly, merchants were extorted, which caused inflation and brought the markets to ruin. Three Quzdughliyya beys, Isma'il, Murad and Ibrahim, contested for power in this period. In 1778 Murad and Ibrahim, followers of Muhammad Bey, forced Isma'il to flee Egypt. Ibrahim, the shaykh al-balad, shared power with Murad. Murad employed Greek technicians to develop a navy and artillery. To raise the necessary revenues, Murad seized the customs and forced the merchants to sell their grain through his monopoly. This was an important innovation, indicating the development of mercantilist economies by the mamluk beys.

When the beys reneged on the obligation to organize the pilgrimage in 1784 and 1785, an Ottoman force under Hasan Pasha intervened and Ibrahim and Murad fled to Upper Egypt. Although an Ottoman restoration under Isma'il was promised, the two rebels profited from a severe epidemic in 1791 which claimed the life of Isma'il and weakened the Ottoman regime in Cairo. Murad and Ibrahim returned to Cairo, defeated the Ottoman forces, and signed an agreement with the Ottoman sultan in 1792. However, the innovations of the beys of the latter half of the eighteenth century shattered the structure of the beylicate and imperial authority. They also increased the involvement of foreigners in the Egyptian economy and society, particularly the French, who sought control of the Egyptian export economy. Therefore, Egypt was in a very much weakened state when Napoleon invaded in 1798.

JAMES WHIDDEN

Further Reading

Crecelius, D. The Roots of Modern Egypt: A Study of the Regime of ‘Ali Bey al-Kabir and Muhammad Bey Abu al-Dhahab, 1760–1775. Minneapolis: Bibliotheca Islamica, 1981.

Gran, P. Islamic Roots of Capitalism, 1760–1840. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1979.

Hathaway, J. “The Military Households in Modern Egypt.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 27, no. 2 (February 1995): 2943.

Hourani, A. “Ottoman Reform and the Politics of Notables.” In The Modern Middle East: A Reader, edited by Albert Hourani, Philip S. Khoury, and Mary C. Wilson. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

Jabarti, ‘Abd al-Rahman al-. ‘Abd al-Rahman al-Jabarti's History of Egypt. Edited by Thomas Phillip and translated by Moshe Perlman. 4 vols. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1994.

Raymond, A. Artisans et commercants au Caire au 18e siècle. 2 vols. Damascus: French Institute, 1973–1974.

Shaw, S.J. Ottoman Egypt in the Eighteenth Century. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1962.

Egypt: Ottoman, 1517–1798: Napoleon and the French in Egypt (1798–1801)

The French expedition to Egypt initiated the modern period of European colonialism in Africa, because it was spurred by strategic, economic, and scientific interests. The strategic importance of Egypt lay in its position on the route to Asia. After 1798 Egypt would be the scene of continual competition by the European powers for influence and political control, particularly between Britain and France. Egypt was of economic importance to France as a source of grain. Moreover, French merchants had been able to market luxury goods in Egypt during the course of the eighteenth century. French and Egyptian commercial relations had suffered during the reign of Ibrahim, who forced the French merchants out of Egypt in 1794. As a result, a commercial lobby in France wanted French intervention in Egypt to secure free trade. The scientific objectives of the expedition were to study ancient and Islamic Egypt, probably to enable colonial occupation. Scientific expertise was certainly indispensable to the project of conquering, administering, and colonizing Egypt. Finally, the expedition exposed Egyptians to modern Europe, beginning a period of interaction that would transform Egyptian culture, society and politics in the nineteenth century.

Napoleon's strategy was to drive toward Britain's empire in India, instead of the proposed invasion of England. The French fleet landed Napoleon's army near Alexandria on July 1, 1798, and broke local resistance on the following day. Napoleon advanced toward Cairo against the mamluk commander, Murad Bey, who fell back and was defeated decisively at Imbaba on July 21, at the so-called Battle of the Pyramids. The mamluk commander, Ibrahim, retreated with the Ottoman viceroy to Syria. Shortly afterward, Nelson destroyed the French fleet at the Battle of the Nile. This victory won the British the support of the Ottoman Sultan, who formally declared war on France in September 1798.

The French conquest of Egypt required an occupation of the Delta and the pursuit of Murad, who adopted guerrilla tactics in Upper Egypt. Aswan was taken in February of 1799 and at the same time Napoleon began his campaign into Palestine. But in neither case were the mamluk forces entirely defeated, as Murad engaged in a continual resistance and Ibrahim joined Ottoman forces in Syria. The French conquest also relied on propaganda, with Napoleon's publicists using revolutionary dogma to attempt to win the support of the Egyptian middle classes against what was described as mamluk tyranny. Equally, it was hoped this would neutralize the Ottoman sultan, to whom the French declared their friendship. The propaganda was produced by specialists in Arabic and printed as bulletins from a press established at Bulaq. The Egyptians nevertheless regarded the expedition as an invasion, rejected the dogma of the revolution, and viewed the scientific works with interested suspicion. ‘Abd al-Rahman al-Jabarti recorded his impressions in his chronicles. From his testimony it appears that the Egyptians resented the foreign presence, viewed Orientalist interest in Arabic texts as cultural interference, as they did the conversion of French officers to Islam, such as in the case of General Jacques Menou.

The expedition nonetheless marks the end of an era, as the mamluk beys never again established their political and social dominance. Having disbanded the old aristocracy, Napoleon turned to the Egyptian notables, marking the ulama, or religious elite, for special favor. The purpose was to rally support for the French regime, and so Egyptian notables were given high positions in the administration. A system of representative assemblies was organized for the localities, as well as the general assembly, al-diwan al'umumi, which was convened in September 1798. Napoleon claimed that the natural leadership of Egyptian society was the ‘ulama’ and that the creation of assemblies would accustom them to ideas of representative government. Yet, ‘ulama’ and merchants were already established as a national leadership, having led several protest movements against the misrule of the mamluk beys in the last years of the eighteenth century. Similarly, there was a revolt in October 1798 against the French regime led by the ‘ulama’ of Cairo. The French brutally suppressed the revolt, executing some members of the ‘ulama’ and dissolving the general assembly. Nevertheless, the French occupation seems to have consolidated the political role of the urban notables and strengthened the national leadership.

In spite of the political experiments initiated by Napoleon, the French regime in Egypt was principally concerned with the collection of tax. The economist Jean-Baptiste Poussielgue created the Bureau of National Domains to administer the former iltizam estates, which were declared state property after the flight of the defeated mamluks. The bureau was directed by French officials, payeurs, who conscripted Coptic tax collectors, intendants, and the heads of the villages, shaykhs, to collect tax at the local level. Under Napoleon's successor, General Kleber, even more radical reforms were begun as the French regime became more entrenched and adopted a defensive posture in late 1799. The provincial districts were reorganized into eight arrondisements, administered by the payeurs, intendants, and shaykhs. At the same time a multitude of existing taxes were abolished and replaced with a single, direct tax payed in cash. Finally, land registration was begun and peasants were given individual property rights. This amounted to an abolition of the Islamic and customary laws of Egypt, bringing to an end a quasi-feudal social order. At the same it began a process of modernization that prefigured much of the subsequent history of Egypt.

After the retreat of the French army from Syria in June 1799, the Ottoman and British armies advanced, landing in Abuqir, where Napoleon defeated them on July 15, 1799. Yet, Napoleon failed in his grand design to control the Middle East and the Mediterranean. He escaped to France the same month. Kleber attempted to negotiate an evacuation of Egypt, withdrawing his troops first from Upper Egypt. At the same time the mamluks infiltrated Cairo and organized another revolt with the support of Ottoman agents and the Egyptian notables. The revolt lasted a month, through March and April 1800. It was crushed only when Murad Bey gave his support to Kleber. On June 14, 1800, Kleber was assassinated and succeeded by General ‘Abdullah Jacques Menou, who rejected negotiation in favor of strengthening the French position in Egypt. It was during this period that the more radical administrative reforms were carried through in Egypt. But Menou suffered a military defeat at the hands of a combined Ottoman and British force on March 8,1801 at Abuqir. Under siege in Alexandria, he capitulated to the allied command in August 1801 and departed for Europe on British transports in September.

The man widely credited with founding the modern Egyptian nation-state, Muhammad ‘Ali, was an officer in an Albanian regiment of the Ottoman army. His first lesson in politics began the last chapter of mamluk Egypt, when the Ottomans attempted to destroy the mamluk commanders after the French departure in 1801. In this instance the British secured the amnesty of the mamluks. After he seized power in 1805, Muhammad ‘Ali finally eliminated the mamluks. But his political ascent relied upon the support of the Egyptian notables. The French expedition strengthened the position of the notables, but it also provided the blueprints for future attempts to strengthen the state. These were taken up by Muhammad ‘Ali, who adopted Napoleon as his exemplar and brought about the modernization of the system of landholding, the military, and the administration.

JAMES WHIDDEN

See also: Egypt: Muhammad Ali, 1805–1849.

Further Reading

Dykstra, D. “The French Occupation of Egypt, 1798–1801.” In The Cambridge History of Egypt: Modern Egypt from 1517 to the End of the Twentieth Century. Vol. 2, edited by M.W. Daly. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

El Sayed, A.L. “The Role of the Ulama in Egypt During the Early Nineteenth Century.” In Political and Social Change in Modern Egypt, Historical Studies from the Ottoman Conquest to the United Arab Republic, edited by P.M. Holt. London: Oxford University Press, 1968.

Girgis, S. The Predominance of the Islamic Tradition of Leader-ship in Egypt During Bonaparte's Expedition. Frankfurt: Herbert Lang Bern, 1975.

Herold, J. Christopher. Bonaparte in Egypt. New York and London: Harper and Row, 1962.

Jabarti, ‘Abd al-Rahman al-. Napoleon in Egypt, Al-Jabarti's Chronicle of the French Occupation, 1798. Translated by J.S. Moreh. Princeton, N.J.: M. Weiner Publishing, 1993.

Shaw, S.J. Ottoman Egypt in the Age of the French Revolution. Cambridge Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1964.

Egypt: Ottoman, 1517–1798: Nubia, Red Sea

After waves of pastoral incursions between the thirteenth and sixteenth centuries, Nubian society was reduced to Lower Nubia, the area between Aswan and the third cataract. Upper Nubia adopted an Arab identity through Arabic and Islam; it also came under the sway of the Funj Sultanate of Sennar. Another result was that Nubia was no longer the important intermediary between African and Mediterranean commercial systems. The trade in gold, ivory, and slaves was in the hands of the Islamic sultanates of Dar Fur and Funj. Consequently, the economy of Nubia declined, as the pastoralists encroached upon the Nubian farmers of the Nile valley. When the Ottomans annexed Nubia in the sixteenth century, all trace of the prosperous societies of the Christian kingdoms had been erased.

Although Nubian traditions claim that Nubia was conquered during the reign of Selim I, it seems that the conquest took place between 1538 and 1557, during the rule of his successor, Sulayman the Magnificent. The conquest was staged from Upper Egypt in an expedition that might have come after an appeal made by the Gharbia, an Abdallabi or Ja'ali ruling group. The appeal was made to the Ottoman sultan by the Gharbia against their adversaries, the Jawabra. The campaign was led by Ozdemir Pasha, a mamluk officer, who was perhaps directed to engage in a campaign against Funj, which had expanded from the confluence of the White and Blue Nile to Lower Nubia. It is likely that a battle took place at Ibrim and the defeated Jawabra fled southward to Dongola. According to Abdallabi traditions, the Funj defeated the Ottoman troops in a subsequent battle. This reputedly took place at Hannik, near Kerma, probably in the early seventeenth century. In any event, Hannik became the southern boundary of Ottoman Nubia.

The Ottoman ruler of Nubia was given the rank of kashif, a mamluk term for the head of a province in Egypt. Therefore, Ottoman Nubia had a status similar to an Egyptian provincial district. The Ottoman tax system was imposed, but Ottoman firmans, or decree laws, exempted the cavalry from having to pay tax. So, just as the kashifs established a hereditary ruling house, the cavalry evolved into a privileged aristocracy, known as the Ghuzz. The kashifs and Ghuzz resided in several castles, notably those of Aswan, Ibrim and Say, although there were several others.

The kashifs were the appointees of the Ottoman authorities, nominally responsible to the Egyptian viceroy, who paid them a salary. Equally, the kashifs were obliged to pay an annual tribute to the viceroys. Tax was collected from the Nubians by a display of superior force, during regular tours of the Nubian villages. Therefore, the kashifs created their own private armies, composed of members of the ruling lineage and slaves. The Nubians paid their taxes not in cash but in sheep, grains, dates, and linen. This provided the kashifs with trade merchandise, enabling them to count their wealth in cash as well as in slaves. The European traveler Burckhardt observed at the beginning of the nineteenth century that Nubian subjects were victims of slave raids if their conversion to Islam could not be proven. The kashif ruling lineage also intermarried with the local, Nubian lineages, providing another means to increase the size of the ruling house, as well as its properties, which were extorted from the Nubian lineages.

By the eighteenth century, the Nubian kashifs ruled as independent monarchs of the Upper Nile Valley, much like the mamluks in Egypt. The annual tribute to the Ottomans was not paid, and emissaries of the sultan could not expect free passage through Nubian territory. The Ottoman connection remained only as a theoretical guarantor of the privileged position of the kashifs and the Ghuzz in Nubian society. As a consequence of the warlike nature of these elites, the Nile Valley above the first cataract was an insecure trade route and caravans were forced to take the arduous desert routes. The inclusion of Nubia in the Ottoman Empire did, however, enable Nubians to migrate to Egypt, which has since become a common feature of Nubian society. Nubians fled southward also, to escape the kashifs and to engage in trade. Some went on a seasonal basis to engage in caravan trade among Egypt, Funj, and Darfur, or found employment in Egyptian markets and industries on a permanent basis.

The Ottoman period in Nubia continued the process of Islamization in Nubian society. The Ottoman elite became integrated into the lineage systems established by the Arab nomads, resulting in social stratifications in which the Nubians were a subject peasantry. The kashifs and Ghuzz, meanwhile, lived in the quasi-feudal style of a military aristocracy, much like that established by the medieval Christian kings.

A similar process occurred in the Red Sea after the Ottomans occupied the mamluk port of Suez, where they built a fleet to control the lucrative Red Sea trade to India. Trade had already been intercepted by the Portuguese, who landed emissaries in the Red Sea, near Massawa, in May 1516 and April 1520. The first Ottoman expedition to the Red Sea brought the Ottomans to Yemen in 1538. Afterward, Ozdemir Pasha descended from Upper Egypt to the port of Suakin on the Red Sea to forestall the Portuguese advance. The port of Massawa was taken in 1557. By 1632 the Ottomans had shut the Red Sea ports to all Europeans, while the Portuguese contained the Ottoman fleet in the Red Sea. At the same time, Africa became a battleground between Christians and Muslims in the Horn. The Muslim Imam, Ahmad Gragn, was defeated by Christian Ethiopia with Portuguese assistance in 1543.

The Ottoman province of Abyssinia, or Habesh, was situated in the region between Suakin and Massawa. Ozdemir Pasha built fortifications and a customs house at Massawa and left the port under the command of the agha of a Janissary troop. Suakin became the center of Ottoman power in the Red Sea, with a garrison of Janissaries under a governor with the rank of sandjak bey. When the Red Sea lost its important commercial importance in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries with the decline of the spice and coffee trade, Ottoman authority on the African coast evaporated. The ports fell under the nominal authority of the pasha of Jidda. By the mid-eighteenth century even this connection was severed when the aghas discontinued their nominal payment of tribute to Jidda.