![]()

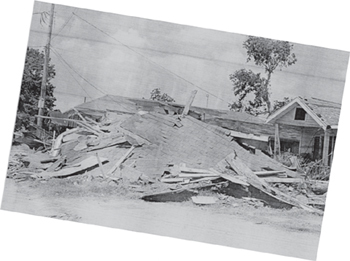

THE EFFECTS OF HURRICANE KATRINA, NINE MONTHS

AFTER THE STORM. (AMY GREBER)

MY FATHER’S FIRST CAR could only turn in one direction. It was a 1940 Plymouth, and whenever Dad turned left, the right front wheel would suddenly lurch, the bald tire tilting, the car stopping fast. Dad bought the old clunker in ’56, shortly after his sixteenth birthday, and only a mix of creativity and teenage resourcefulness kept it running. The gas pedal was a beer can. The gear shift was a screwdriver. The upper front frame was held together with a men’s leather belt. When the car hit high speeds—or turned left—the belt would slide from the frame, and the wheel would slide from the car. So it was right turns only. Slow right turns. In Arlington, Virginia, the urban Washington, D.C., suburb where Dad spent his high school years, he’d make three right turns to avoid going left.

“You’d be surprised,” he once told me, “how far you can go turning just one direction.”

I was thirty-nine when Dad collapsed. He’d finished eighteen holes of golf when he fell outside the clubhouse, his buddies inside ordering late morning beers. I’ve often wondered if Dad’s life flashed before his eyes, though I know it’s a foolish notion: the body doesn’t respond to cardiac arrest with a montage of classic clips. And yet as soon as I got the call, his life flashed before my eyes—or at least the parts of his life that I knew. The old Plymouth with the unreliable wheel. My parents’ honeymoon at an Arlington pizza joint after the courtroom ceremony. The time as a farm boy when he fell from the roof of a barn.

I thought back to his retirement party the summer before in San Francisco, one of the great nights of his life. What made that party so remarkable wasn’t simply the throng of guests—colleagues from twenty years earlier attended—or the happy buzz in the restaurant party room. What made the evening so memorable, so stunning, even, was that Dad had laid off at least a third of the jolly guests a few months before. The company was moving its manufacturing operation back to Japan, and Dad went from overseeing production of MRI units to closing the facility. Which is why the crowded room of pink-slipped partiers was so odd. Who celebrates the guy who killed your job? Who poses for pictures with him, hugs him, shares old war stories? Who gives their hard-earned cash to buy him a freaking gift? It’s beyond my comprehension. Like your ex-wife marrying your divorce attorney and you being so delighted to attend the wedding.

I watched Dad laugh with old colleagues when his friend Kevin, an ex-cop with fullback shoulders, corralled me for a chat. It was Kevin, a member of Dad’s leadership team, who noted all the recently-let-go workers in the room. Until I spoke with Kevin, I’d never known about Dad’s long battles to protect employees, to keep them on the payroll as long as possible, to preserve jobs as part of a small research-and-development operation that would remain behind.

“I was in a lot of the meetings,” Kevin said. “The Japanese wanted to give everyone a basic severance package. But Bob—your dad—he has this blue-collar compassion. He kept pushing and pushing for something better. And just about every employee got a management-level severance package. If they didn’t get that, they got more than they would have otherwise.”

The postbuffet, postdessert speechifying had a tone similar to Kevin’s. Colleagues praised Dad’s generosity and work ethic. Mr. Yakamura, Dad’s bespectacled, gray-haired Japanese boss, recalled my father’s Zen-like calm during emergencies. Dad always joked that the only Japanese words he knew were dai mondai—“big problem.” When those dai mondais surfaced—they weren’t infrequent given the cultural differences—the Japanese execs would summon Dad, asking: “Where is Bob-san!”

Finally it was Dad’s turn to speak. He held the microphone but said nothing, staring at the floor. A few weeks earlier he’d shaved off the mustache he’d worn for twenty years. Without it his eyes seemed wider behind his glasses.

He shuffled a bit, put a hand in his pocket. He thanked everyone.

“I’ve been so lucky,” he said, looking out over the gathering, at the white icicle lights gleaming against the walls. “Everywhere I’ve worked, someone took a chance on me. People saw something in me. They believed in me.”

Few people in the room knew it, but Dad never went to college. He was embarrassed by this hole in his résumé, though it fueled his drive and ambition, his quiet empathy. Dad knew what it was like to be unemployed—it happened for an uncomfortable spell when I was in high school. He knew what it was like to work two jobs—he did it while my mom was pregnant with my sister. He knew what it was like to work twice as hard as the other guy because that guy had a master’s degree and you had a certificate from a correspondence course.

The next morning, Dad was still glowing. We sipped coffee on the patio of my parents’ home near San Jose, me and Dad and Julie, my mom enjoying her traditional morning Diet Pepsi. Julie inspected the digital camera Dad received as a gift.

I told him what Kevin told me; how Dad had helped those who’d lost their jobs. He shrugged it off, but I pressed him, and he told me something I’d heard him say before. That you can’t just look at things from your perspective. That you can’t really understand people if you don’t put yourself in their position. Then he sipped his coffee, and he said something I hadn’t heard him say. “Remember, Budo”—my old family nickname—“you succeed when others succeed.”

The night of the party, amid all the good vibes and food and laughs, Kevin mentions something in confidence that surprises me.

“Your dad has some serious regrets,” he says in low tones. “He thinks he didn’t spend enough time with you and your sister because he worked so much.”

“Really? He thinks that?”

“Yeah.”

Really?

It’s like saying, Your dad regrets having eyeballs and nostrils and testicles. This is who he was. He’d sit on the couch at night, manila folders spread on the cushions, a report in his lap, open briefcase on the floor. He’d work late, he’d work weekends. He had a zest for spreadsheets that most people reserve for heroin or chocolate cake. So yes—Dad worked a lot. And Mom, as most moms do, bore the everyday labors of parenting: feeding us, dressing us, disciplining us. But Dad never skipped Christmas plays or Pinewood Derbies—he slaved over our little red car with the nail for a steering wheel—and I knew, always, I was more important than his work.

Maybe I should ease his regrets. You know—some mushy Hallmark moment where I say, “You’ve always been an amazing dad.” Where I tell him he’s not just the smartest man I know, he’s the best man I know. But I say nothing because … C’mon. We’re guys. We’re not weepy, confessional types. Besides—he’s retired now. My parents sold their house in California. They’re coming home to Virginia. He’ll be close.

It’s the weekend after Father’s Day: I make a dinner reservation at Dad’s favorite restaurant—our belated gift—then walk to the pool in the townhouse community where Julie and I live. It’s hot out. Humid hot. Miserable hot. Dad is playing golf that morning with his usual Saturday foursome and I think—

How in the hell can he play in such God-awful heat?

The golf has been good for him, slimming his belly. He looks fit, trim from the walking and working on their new house: painting, building shelves, landscaping. His golfer’s tan is a deep bronze, his arms abruptly pale at the sleeves. I’d thought he’d struggle with retirement, but he has enough projects, for now, to stay busy. “It wasn’t fun anymore,” he says of his career. “If it was still fun, it would have been harder to retire.”

I’m sweating when I return home—so much for the refreshing swim—and the air-conditioned foyer feels like another, better world. Julie walks from the kitchen and stops me as I close the door.

“Your mom just left a really weird message.”

I take off my sunglasses, hit “play” on the answering machine. Mom’s message is unintelligible. I call her at home. No answer.

I grab my cell phone. Water rolls from my bathing suit to my ankles.

She’s crying on the voice mail message.

I wonder if she’s sick. I was just telling Dad last week that I worry about her. She smokes—though Dad does, too—she doesn’t eat right, she doesn’t exercise. Amid her heaves and sputtering I hear only a few words, like a distress call that’s largely static: Dad has collapsed.

I call my sister. Dad was rushed from the golf course to Fair Oaks Hospital. I scramble to put on dry clothes, throwing on a T-shirt from a park in West Virginia where Julie and I went mountain biking. I know I wore that shirt because I couldn’t bring myself to wear it again for more than a year.

Julie and I hop in the car. We don’t speak the entire drive. It could be anything, I tell myself. Probably heatstroke. Dehydration. Dad had experienced some light-headedness of late—probably tied to a new blood pressure medicine, his doctor said—but a week ago he easily passed a stress test.

It could be anything. Relax.

We arrive at the ER. Mom is outside, talking on her cell phone, smoking. I jump out of the car. Julie moves to the driver’s seat to park.

Mom rushes toward me, throwing herself against me, sobbing into my chest.

“Daddy died,” she moans.

I hold her. I stroke her head as she cries. But for a moment it’s like I don’t exist. No thoughts, no nerves … nothing.

Mom and I walk toward the ER doors like survivors of a bombing, holding each other up. A stocky cop offers his condolences and shakes my hand. The hospital pastor does the same. It’s been two minutes since I heard the news.

We’re led to a small, indiscriminate room; a room of bland white paint, the bland furniture of interstate hotels. Every table has a box of tissues. The tragedy room. A place for instant grief and long forms on clipboards.

I want a moment alone with Dad. A nurse leads me past imposing wood doors down a white hall. His body is on a gurney, half surrounded by a curtain, a white sheet up to his chest, his red golf shirt still damp.

I stand by him. I speak. I make promises.

Everything changed for me that day.

It wasn’t just that I lost my father. When life works the way it’s supposed to, your parents die before you. I know that. I’m glad he died quickly, doing something he loved. I’m glad he never suffered the indignities of old age, the pain of cancer, the horrible haze of Alzheimer’s. I tell myself that frequently, and yet beyond just missing him, and mourning him, I’m forever jarred by the way we lost him. The morbid speed of it all. His memories, his hopes—everything—gone. Extinguished. The time it takes to clutch your chest and crumple to the earth.

My father and both his parents died suddenly in their sixties. They all led harder lives than me. And yes, they all smoked. The risk factors were higher. But who knows? Maybe a coronary time bomb is ticking in my chest, too. Maybe a genetic “off” switch lurks in my heart, programmed for my sixty-fifth year.

It’s not even dying that bothers me. It’s dying without making a difference in the world. Without doing a damn thing that matters. After Dad died—“The big sad news,” as one of his former Japanese colleagues put it—we received heartfelt letters and e-mails from the people who loved him, and I read and reread them all.

“When I think of Bob, as I do frequently these days, I recall him as a great influence on my life,” wrote Will, the HR director where Dad worked.

“I don’t think I would be the person that I am today without knowing him,” said Steve, another of Dad’s employees.

“I may dream to play golf with him at ano-yo [heaven] some day,” wrote Kyoto Tanaka, one of Dad’s first Japanese bosses and his close friend. “His score will be 95 and my score will be 96.”

By saying Dad will have the better score, Mr. Tanaka said his friend was the better man.

I read these letters and wondered: What will people say when I’m gone? What if my own life ends in an instant? What have I accomplished? These feelings weren’t new. Dad’s death simply ignited them, exposed them, ripped them from my secret shell. I’ve long wanted children, and in the weeks after the funeral I made my most emphatic case to Julie. It’s not too late, I said. We’ll conceive. We’ll adopt. We’ll build a child from a kit. We’re cheating ourselves out of the central experience of life.

She agreed to consider it, but I became morose. I found myself acting like things were normal—still smiling at work, still soldiering through middle-class routines—but I was lost. My life didn’t stand for anything. I had no purpose, no passion, no mission.

Months later, Julie’s sister gave birth to a son. When her mother left the happy message on our answering machine, I felt … anger. Long-submerged anger. Anger that surprised me with its intensity; jealousy that startled me with its bite.

“What’s bothering you?” Julie asked the next day.

“I don’t want to talk about it,” I snapped. But I knew that we must.

Late that night, Julie was in bed, under the covers, reading a mystery. I paced downstairs before heading up and entering the bedroom. I sat beside her. We’ve been friends since the sixth grade. Married for fifteen years. I’ve loved her for all that time put together. We talked. She had thought about children many times since we’d last discussed it. But…

But.

She looked at the book in her hands.

“I just don’t have maternal feelings,” she said.

Sorrow softened her voice. A sadness that seemed to say, I want so badly to do this for you, but I can’t.

When Julie was about three years old, a drunk driver killed her older sister. That day—the anguish of that day—is one of her earliest memories. I’ve always believed, though Julie disagrees, that something happened that day. That somewhere inside, that stunned little girl determined that she would never, ever subject herself to that kind of pain. The pain of grieving parents.

On the day Dad died, I never cried. I wanted to be strong for Mom. It was only the next day that I wandered away from visiting relatives, walked out of my sister’s house, made the five-minute trek in the heat to my parents’ nearby home, sat on their bed, alone, and wept. I could only lose control if I was in control. I could only cry on my own terms. But on this night, sitting on the edge of the bed with Julie, I finally—unwillingly—lost that carefully maintained control.

I needed an escape. I needed an outlet for wasted energies. I needed a way to tackle my grief: my grief at losing my father, my grief at not being a father.

A few months later the e-mail arrived. The subject: “Katrina Relief Volunteer Opportunities.” My employer was working with Rebuilding Together, an organization that repairs homes owned by low-income older Americans. Rebuilding Together was managing projects in New Orleans and throughout Louisiana, and ten to fifteen slots were available for volunteers to do hot, hard work for one week in the Big Easy, nine months after Hurricane Katrina had devastated the city.

“Employee volunteers will work under hardship conditions,” the announcement said. “Accommodations will be provided in a tent city and/or on cots in facilities such as church basements. Three simple meals will be provided daily, and dietary restrictions cannot be met. Employee volunteers must be in good health and capable of hard physical work.”

Without discussing it with Julie—without even knowing what the job would be—I signed up.

From the window of a cramped airport shuttle van, as I travel east on Interstate 10—a route that nine months earlier was underwater—the city of New Orleans seems almost healthy. Through smudged glass I see a few crude plywood patches on the roofs of houses, the occasional abandoned strip mall, the silhouettes of workers on the Superdome’s half-repaired roof. In the French Quarter, the old homes with their long shutters and iron gates seem free of Katrina’s scars. “You’re standing in the twenty percent of New Orleans that didn’t get any flooding,” the owner of Crescent City Books tells me that afternoon in his shop. On Canal Street, the reopened Harrah’s casino beckons gamblers to eat, drink, and lose money; dirty Bourbon Street entices out-of-town drunks with stiff Hurricanes and big-boobed contortionists on trapeze swings.

Now that I’m here, I’m not sure why I’m here. I have no talents to offer the city. My primary professional skills—writing and editing—aren’t exactly in high demand. (“Thank God the editor’s here—we’ve got one hell of a compound modifier problem …”) Not that any of this occurred to me when I signed up. I was aware of my feeble ability in all things hardware, but only when I spoke by phone with Cynthia, Rebuilding Together’s disaster relief coordinator, about two weeks before the trip, did I realize this was an issue.

“So,” Cynthia asked me, “what kinds of skills do you have?”

Skills?

No one said anything about needing skills.

I spared Cynthia the long, bullshitty answer—“Well, that all depends, of course, on how you define skills”—but my “skills” are basically limited to this:

1. Sarcasm

2. Spinning a basketball on my right middle finger for upwards of ten seconds

3. Quoting large sections of old Simpsons episodes

And that, sadly—really sadly, I realized, during our long-distance silence—is pretty much it. I can handle a drill and a hammer, I’m decent at replacing the innards of toilet tanks, but I’m about as qualified to operate a band saw as I am to give birth.

“That’s okay,” Cynthia said. “We have plenty of work for unskilled people.”

As Cynthia explained it, rebuilding projects seesaw between skilled and unskilled labor. The unskilled folks start first on a broken-down home, tearing down moldy drywall, ripping up floors; work that could be done by anyone with two hands and half a brain (me). After that, the skilled people—contractors and construction pros who volunteer their services—arrive to rewire homes, rebuild roofs, replace appliances, reinstall torn-out drywall and floors, and do any other jobs best performed by nonamateurs who know what they’re doing. Unskilled volunteers then return to paint, haul trash, and help residents move back in.

I tell Cynthia that I’m pretty confident in my ability to haul trash.

Our accommodations are lovely, which is disappointing. I was welcoming hardship conditions, because when you’re trying to figure out your life, severity is more illuminating than comfort (and when you’re trying to help those who have suffered, you want to know what they’ve endured). But we the eager volunteers—about fifty of us are here from around the country—are not staying in a tent city as we’d originally been told. Nor are we sleeping in church basements, like many other volunteer groups, or in cramped, no-frills trailers.

We’re staying at the New Orleans Marriott.

I know. There’s something deeply wrong about this. It’s like the Buddha seeking enlightenment in a limo.

The Marriott rooms are courtesy of the Order of Malta, a Roman Catholic organization that is some nine hundred years old and—I suspect—has Da Vinci Code–like plans for world domination. Based in Rome, the order is led by a Grand Master and Knights of Justice, and its red-and-white logo resembles a medieval shield (the Malta fleet waged war throughout the Crusades to “defend the Christian territories in the Holy Land”). As a sovereign subject of international law, it issues its own passports. The major flaw in my take-over-the-world theory is that the order’s altruistic mission, Tuitio Fidei et Obsequium Pauperum—“defense of the faith and assistance to the suffering”—has inspired centuries of good deeds. Here in New Orleans, the Maltas are providing not only unskilled older labor—many of the volunteers appear to be over the age of sixty-five—but also $1.3 million in a partnership with Rebuilding Together. We’ve all received red or blue Malta baseball caps, and our new yellow-and-white work T-shirts prominently display the Malta logo. As for the hotel rooms, apparently a high-ranking Marriott executive is a Malta, and rumor has it he worked out a deal: volunteers can stay for free if Rebuilding Together rebuilds homes for some Marriott employees.

The only inconvenience—a minor one, I grant you—is that I have a roommate. Obviously this doesn’t qualify as a hardship given the agony this city has suffered and since, I’m guessing, the tent city doesn’t have cable television or those cute little bottles of hotel shampoo. But there is something awkward about sleeping and showering in a modest-sized hotel room with a total stranger.

That stranger is a Californian named Antonio, and we work for the same nonprofit, which has donated money to Rebuilding Together. Antonio works in accounting outside of Los Angeles, while I’m an editor with the organization’s magazine in D.C. The good news—aside from the fact that the room has two beds—is that Antonio is an affable guy (not that one expects humanitarian projects to attract serial killers). We meet when I return to the room after strolling the city, still full from a shrimp po’boy at a nearby dive.

“Hey, buddy!” says Antonio with a firm handshake, dropping the remote control as he hops up from the bed.

Antonio exudes energy. He’s thin: a hiker and a beach volleyball player back in Long Beach. As we make small talk of the “how was your flight” variety, I realize we’re total opposites: I’m tall, he’s not; I’m an introvert, he’s an extrovert; I’m married, he’s single; I’m East Coast, he’s West Coast (though a native of Colombia who grew up in Puerto Rico). Antonio is one of those guys who enter a crowded room and within fifteen minutes know everyone’s name. He is outgoing, upbeat, charismatic, enthusiastic, and a real people lover. Despite that I think we’ll get along fine.

Any illusions about the health of New Orleans are shattered on the first morning’s bus ride to our work site. We drive through the Lower Ninth Ward and stare at empty apocalyptic neighborhoods, deserted homes with brown watermarks like grim tattoos, bitter graffiti with messages like:

Fix

Everything

My

Ass

The dingy siding of one home is a makeshift billboard in sprawling white paint: “Our government cares more about foreign countries than us.”

Watermarks line most homes three feet or so above the dirt and clumps of uncut weeds, but that’s simply where the floodwater settled. In many areas the water rose up to ten feet higher. Some homes have multiple watermarks as the water lowered then settled, lowered then settled.

We pass the occasional FEMA camp: fenced-in trailer parks with trailer offices and residences. Trailers also sit in random front yards, serving as temporary homes for residents. For every home being rebuilt, endless others sit eerily abandoned, phantom neighborhoods in a silent, vacant sprawl. Spray-painted by front doors is an X mark. On the right and left of the X are dates showing when rescue workers inspected the home. In the bottom of the X is a number: how many bodies were found.

Windows are boarded, mounds of trash heaped at the ends of driveways. Stores and strip malls are empty as well, and may never come back.

“This looks a lot better,” says Luther, our bus driver, as we pull through a deserted neighborhood. “A lot of the trash has been cleaned up.”

Trash is good. The nicely collected piles mean people are coming back and cleaning up. Where there is trash, there are people. “That’s why there aren’t any rat problems,” says Luther, who’s also a minister. “No people, no rats.”

The houses don’t seem too battered on the outside, but they’re unlivable on the inside, wracked with mold and water damage. Building supplies are limited. Rebuilding Together’s warehouse was flooded and later looted. Mark, a thirtysomething guy who works for the Order of Malta, says it took four weeks to find kitchen cabinets for one home. “You can’t just go to Home Depot,” he said at an orientation dinner at the Marriott. “Nothing is normal here.” The city fell from 460,000 residents to 180,000 after the floods, so many businesses are understaffed: stores, restaurants, hotels.

“Think of it this way,” said Mark. “You’re in a huge construction site of one hundred thousand homes. You’ll be driving down the road—this happened to me—and suddenly there’s a hole the size of a car; something the city dug to restore water. And traffic is insane because of the construction and closed roads and people coming back in the evening to work on their homes.”

Underneath an overpass are abandoned cars. The vehicles are dented, dirty from submersion in muddy water, broken windshields and brown waterlines along the windows; stretching in rows, like weary soldiers in formation, for what seems like miles. Imagine a long, open garage for ghost cars—“The world’s largest junkyard,” as Luther calls it. We drive past them twice a day. After a while, they become a rusted blur.

“They’re not organized in any way, so it’s just about impossible for people to find their cars,” says Luther. “Not that they would run anyway.”

The bus drops us off at a single-level brick house on Coronado Street in New Orleans East, which is where we’ll work. Our merry band of volunteers is split into two groups—the red team and blue team (hence our different colored Malta hats, I realize)—and sent to two different projects. Antonio and I are on the red team. A white trailer sits in the front yard, along with assorted odds and ends—an old stationary bike, a faded black tarp covering who knows what—but overall the home is in good shape. Much of the interior work is finished, from new walls to new ceilings. The main priority is interior and exterior painting, though some volunteers will rip out the dingy kitchen floor. A Porta-Potty stands at attention next to the driveway.

There’s a mad, enthusiastic scramble to grab paintbrushes and tools as we descend from the bus. Two college girls are ostensibly in charge and divvying up assignments, though they lack the you-do-this, you-do-that management skills of a foreman. At the blue team site, within the first hour, a college guy gets smacked in the mouth with a two-by-four, knocking out a tooth and sending him to the ER.

I receive my first task: scraping white paint from a wood workshop out back. It’s the kind of stimulating work one normally associates with prison road crews, but it’s work that needs to be done, and it’s a good match for my skills (or lack thereof). So I stand in the small backyard, alone, and I scrape, scrape, scrape, and though it’s simple work, it’s hard work, because if this cracked paint could endure one of the five most lethal hurricanes to strike the United States, it certainly isn’t daunted by unskilled me.

The sun roasts my neck and arms as I scrape. I’m a lifelong Virginian, so I’m conditioned to humidity, but the steamy May heat feels like July back home. Except the clouds seem more scarce, the sun more intense. My morning goes like this:

Scrape, scrape, scrape.

Sweat, sweat, sweat.

Scrape.

Sweat.

Wipe face with shirt.

Chug water.

Repeat.

It’s easy to think paint scraping is futile given the scale of the destruction. But one thing I’ve slowly learned in the ten months since Dad died, something I’m still only beginning to grasp, is the significance of small gestures. On the evening of Dad’s death his friend Joe drove me to the golf course, the now infamous golf course where Dad died, to pick up my father’s car. Here was a task, one of many, that would never have occurred to me when I woke that morning.

If your father’s heart implodes, you’ll need to get his car.

Joe drove fast, too fast, face ashen, zooming down a twisty two-lane road in his convertible. The top was down; Joe’s graying hair flapped in the wind. Over the past year, Joe had gone from distant acquaintance—my sister’s boss’s husband—to Dad’s golfing buddy and good friend when my parents moved home. Dad filled a hole in Joe’s Saturday foursome; Joe filled a hole in Dad’s postretirement life. He was there when Dad collapsed.

“We’d all gone to the clubhouse to get a beer,” Joe told me, yelling over the wind and the engine as we drove. “Your dad sat down on a bench outside. We thought he’d gone to the bathroom. Some guy saw him sitting there and said, ‘Hey—I think there’s something wrong with your friend.’”

The car hugged a curve; Joe shifted gears and roared down a straightaway, the trees a blur on either side. It was like being in a cop movie.

“He’d been joking about how healthy he was after acing his stress test,” Joe yelled. “He was so relieved.”

The parking lot was largely empty when we arrived. Joe got out and lit a cigarette, paced a bit, then stared at the spot in the green grass where the crowd had formed. I thought about asking him to show me the exact spot, to re-create the incident, to satisfy my sudden detective hunger. Instead I watched him, the cigarette smoke rising from crossed arms. It only occurred to me much later, given my own shell-shocked state, that this was the last place Joe wanted to be. It was too soon to be here; to be where his friend died only hours before. He was here purely to help. And it was something I’ll never forget.

Small gestures.

And so I think about Joe, and I think about Dad, and I scrape harder.

As will become our nightly routine, Antonio and I lie in our separate beds, tired, pillows propped up, watching the NBA playoffs. It’s a fitting TV choice, since my full stomach resembles a basketball. We ate dinner earlier with the volunteers in a Marriott ballroom: grilled salmon with stewed tomatoes on a bed of potatoes, plus two pre-dinner beers for me. I told Mark I felt guilty staying here instead of the tent city.

“Actually the tent city is quite nice,” he said. “The food is good, they have washing machines, showers…”

Yeah, sure. It may be nice, but it’s still a tent city. I doubt the folks there enjoyed a delightful raspberry tart with coffee for dessert.

Before dinner, while I nursed my beer, Antonio mingled with the other volunteers, as if every stranger were a friend.

“I never thought I’d be meeting knights and dames,” he says back in the room, talking about the esteemed elder Malta volunteers. “That Margaret sure is interesting.”

“Which one is Margaret?”

“You know: Margaret. Worked at ABC News and was married to a senator. She was sitting there with Jim.”

Jim…

“The guy who was a developer.”

On the TV screen, Steve Nash shoots a free throw. I pick up my cell phone.

“Louisiana is on Central time, right?”

“Central time,” he says.

“So we’re an hour behind home. I wonder if I should call my wife.”

“Hey, you don’t want to get in trouble with your wife.” He clicks channels during a commercial. “So what’s your wife’s name?”

“Julie,” I say, realizing how little I’ve revealed of myself. “She’s a nurse practitioner. Which means she does more diagnosis stuff than an RN, and she can write prescriptions. She works at a university, in the student health office.”

“Man, I couldn’t be a nurse or a doctor.”

“Me neither. You gotta have the right personality. I couldn’t do any job that involves phlegm.”

Sometimes if I call Julie at work I’ll jokingly ask, “So—have you healed anyone today?” But she really is a healer, even if she doesn’t see herself that way. Recently our dog, Molly, developed a nasty sore near one of her back paws. Every night, Julie sits on the floor and soaks it, and cleans it, and wraps it in gauze.

I don’t talk with many people about our kid quandary, but I once told a friend of mine about Julie’s dog care. “Sounds to me like she has maternal feelings,” she said. “She just has a four-legged outlet for those feelings.”

Antonio flips back to the game. I look down at my phone. It’s too late to call.

It’s our second day of work and by lunchtime I’ve already gulped down three bottles of water. Yesterday I drank six bottles, but thanks to the heat and my energetic sweat glands I made just one trip to the driveway Porta-Potty. And that, believe me, is a blessing, since the Porta-Potty bakes all day in the Louisiana sun.

I spend most of my morning painting the carport ceiling and all its upper carport crannies, a natural job for my long arms. As I dip my roller in a tray of white paint, the homeowner, Lucille, and her two middle-aged daughters make a surprise appearance to check the progress and say hello. Lucille is a tiny woman, probably approaching eighty (though I have more gray than she does), and her arrival is greeted with rock-star excitement. Susan, a volunteer who’s been painting shutters with a precision normally reserved for wristwatch repairs or circumcisions, rushes toward her with white-stained fingers and hugs her. Cameras come out. Mom and the daughters grin, arms around each other, posing for our paint-streaked paparazzi. For all the hardships these three good people have suffered—they endured the Superdome in the aftermath of the storm before relocating to Austin, Texas—they’re glowing, not just because Lucille will soon have a house again, her house (one of her daughters lives in the refurbished house next door), but because of the staggering generosity that rebuilt it. There’s a wonderment in their smiles that says—

All of these people—these strangers—have come from across the country to help us. Us! Can you believe it?

I’ve seen this grateful reaction throughout the city. The hotel staff seemed so damned happy when I arrived. Not the phony, robotic “How may I help you” happy you normally receive. This was thank you, thank you, we need people to visit our city, please tell your friends. The doorman’s smile made me feel like a long-lost brother. (Anna, a colleague from D.C., meets a probably not-uncommon exception, talking one day with a tattooed waiter in a French Quarter café who is sick of volunteers. “All the do-gooders are driving me crazy,” he says. “They don’t realize that things move here at a certain pace.”)

At lunchtime we grab box lunches and spread out around the house, from the carport to the backyard. The hardier folks sit in the grass under the front-yard sun, a terrific idea if you like a bit of heatstroke after dessert, but not appealing to a shade guy like me. I opt for the cooler front walkway. My neck is stiff from looking up at the ceiling for hours while painting, and I’m embarrassed to admit that my shoulder is a little sore from yesterday’s scraping, and from applying primer on the workshop. Complaining about it seems unthinkable. Seeing Lucille and her daughters, and their deserted neighborhood … I admire these determined homeowners who have the guts to rebuild and move back; the guts to endure such stress and doubt and uncertainty. I’m not sure I could do it.

Earlier that morning, Mark told one of many survival stories we will hear during the course of the week. “There was this old man,” he said. “I mean, really old. He was asleep on his couch when the levees broke. He woke up and the water was up to the cushions. So he went to his attic. A lot of people used hatchets to hack their way through the roof, but this guy didn’t have one. So he was trapped in the attic with no way out; his home was completely flooded. Think about the heat—it must have been unbearable. And yet somehow he survived. He just endured until someone found him.”

Not everyone was so lucky. Two months after I return home, New Orleans firefighters will find the skeletal remains of a Katrina victim in a Lower Ninth Ward home. It will happen again in December, when workers uncover another skeleton while demolishing a house.

I came here because I felt miserable, but now that I see other people’s misery—not misery because their suburban middle-class lives lack purpose, or because life hasn’t turned out the way they hoped, but real misery; the misery that comes from homelessness, from death and despair, from unthinkable loss—I feel ashamed for feeling miserable. Which, of course, makes me feel more miserable.

I sit on the cement and eat my turkey breast on white bread in silence. Antonio plops down next to me, gives me an elbow to the arm.

“Hey buddy,” he says, winking, then peering into his boxed lunch. “Whew! Man, when we got here that first night, and I saw how old some of these volunteers were, I thought you and I were gonna do all the work. These people work hard! But you know—it’s just good to be helping people, isn’t it?”

I munch on an apple from the box. Maybe he’s right. And then a little thought creeps into my sweat-drenched head.

Remember, Budo—you succeed when others succeed.

A coach-style bus takes us to and from the work sites, the air-conditioning a blessing at the end of the hot days. In the mornings, everyone is groggy, the coffee yet to provide its caffeine spark. In the afternoons, everyone is exhausted. We gaze out the windows at the injured city, finding some previously missed detail—I watch the watermarks rise and fall from one neighborhood to the next—and we ask questions of Luther, the minister–bus driver who enlightens us with his sermons on the city and the hurricane.

“Katrina was God’s punishment for the city’s sins,” Luther proclaims from his steering wheel pulpit. “This city did wrong for too long. So God sent us a flood to sweep up all the murderers and the drug dealers. That’s not to say they won’t be back. Some of them already are back. But God was sending a message.”

God has plenty of reasons to be irked with humanity, but the flooding was the work of man. Overdevelopment eliminated marshlands that once served as natural drainage areas. The levees failed, as did the floodwalls—which the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers had predicted could happen twenty years earlier. As for the criminals, fifteen convicts escaped from Orleans Parish Prison in the post-flood chaos. Eighty percent of New Orleans’ police officers lost their homes. Another 30 percent suffered post-traumatic stress disorder.

Luther’s life has been affected as well. He lives in Baton Rouge, and the drive to New Orleans that once took ninety minutes now takes up to two hours, since so many people now live outside the city and commute to work. His sister, he tells us, used to live in New Orleans—she and her family had sat down to dinner when the levees broke, sending them scrambling to the attic in terror.

“Next time there’s a hurricane, they’ll bus you out the second they hear the word ‘hurricane,’” says Luther. His description of the state’s post-Katrina recovery efforts: “Louisiana has a way of saying, ‘Leave it up to me and I can screw it up.’”

Tracy, a fiftyish volunteer from Sacramento, laughs and nods. I’m sitting next to her on the bus. She has an impressively intellectual résumé: for twenty years she led a bipartisan California think tank before becoming a university professor. I suspect, however, that she’s secretly a therapist, because she has this annoying talent for getting reticent, tight-lipped, closed-off people like myself to discuss things we don’t really want to discuss.

“You never told me why you’re volunteering here,” says Tracy. I’ve ducked the question for days, but now I’m trapped: we’re twenty minutes from the hotel.

“Well,” I say, “I turned forty a few months ago, and, you know…”

“So what was it about turning forty that bothered you?”

I see what she’s trying to do. She’s pressing me for specifics, because the more specific I get, the more I reveal. Well, it’s not going to work. I’m not going to start blabbing like some reality-show idiot and share my existential doubts and disappointments about life and not having kids. I don’t care if she is incredibly friendly, or if she looks like a happy elementary school teacher behind her dark-frame, smart-person eyeglasses, or if she has the type of calm, persuasive nature that encourages you to lie down and pour out your life’s secrets. I’m cleverer than that. In fact, she winds up talking about children, roughly ten minutes after I start blabbing like some reality-show idiot and sharing my existential doubts and disappointments about life and not having kids.

“For a long time I wasn’t sure I wanted children,” she says. “And then I’d see diaper ads on TV, and I’d start crying. That’s when I knew it was time.”

“I haven’t seen Julie crying during diaper ads,” I say.

I fell in love with Julie in the sixth grade: her family moved to Virginia from California, just outside of Pasadena. We lived on the same green-grass suburban court, four houses apart. For years I liked her, liked her in that prepubescent way that’s more intense, more desperate, more painful than mere love. To her I was simply her brother Tom’s friend, but I knew that one day Julie and I would be together. I can remember hearing Bob Seger on my clock radio as a dopey fourteen-year-old, convinced the song was right: Someday lady you’ll accomp’ny me.

Our first date was my junior prom. 1982. Julie was a sophomore. She’s two weeks older than me, but I was a grade ahead: in kindergarten I was promoted to first grade because I could read Green Eggs and Ham. Sadly, I reached my academic peak as a five-year-old.

For the prom, I wore a tan corduroy three-piece suit from JCPenney. Julie looked beautiful in a pink-and-white gown, which by today’s thin-strap, look-at-my-cleavage standards seems almost Victorian. I drove us in my mom’s Smokey and the Bandit–style Trans Am, a silver car with the big-winged orange-and-red bird on the hood, a cool-at-the-time improvement over my humble Volkswagen squareback.

We broke up after my senior year in 1983: Julie started dating the manager of the McDonald’s where she worked. He drove a Firebird, certainly sportier than my VW, though it didn’t have a hood. (Let me repeat: it didn’t have a hood.) About a year later we reconnected. We were married in 1991.

I always assumed we’d have kids. My parents had kids, her parents had kids—it seemed like a natural. An inevitable progression in life. We started with houseplants, graduated to fish, made the leap to a dog. A tiny human would surely be next.

But then we hit thirty, and thirty-five, and still no little one was scurrying through the house; no child to love us, infuriate us, worry us. Julie worked in a pediatric office, which didn’t help. When you handle sick, screaming kids eight hours a day, you generally don’t race home and say, I beg you: impregnate me—NOW. As the years passed, I struggled to discuss the issue, perhaps because I knew its conclusion: Julie, whether because of her sister’s long-ago death or because she wanted her freedom, was content with a childless life. And a silent sadness took hold of me, a malaise dragged to the surface by the slightest events: birthday parties for our friends’ kids, soccer games at the field near our house. That should be us, I’d think. Why the hell isn’t it us? And it would hit me, like a type of paralysis—

We may never have children. I may live my entire life without holding a son. Without holding a daughter. I may never have a relationship with a child like the one I had with my dad.

Julie and I are forty. The clock isn’t just ticking; it’s shaking us by the shoulders and screaming, “I’m ticking, you idiots! Can’t you hear me ticking!?”

I don’t have maternal feelings, she’d said. I respect those feelings. And I’m glad we never conceived a half-wanted child. Julie is a wonderful woman. She has devoted her career to caring for others. When my mother needed surgery for pancreatitis, Julie accompanied her to talk with the surgeon. When my grandmother needed monthly B12 shots, Julie would jab her arm, sparing her a trip to the doctor. I receive more from her than I give in return. She is the best part of me. And yet knowing all this doesn’t make it easier.

Cindy, one of the college-age quasi-foremen, needs a few volunteers to help install a laminate floor at a house down the street. I quickly raise my hand. It’s a chance to do something different, see a new home, learn a new skill.

Four of us work on the floor. The unskilled laborers are me and Keith, a volunteer from Sacramento who looks vaguely like Billy Carter. The skilled half of the team are Justin and Frank, two California contractors. Justin shows us how to install the rectangular floor pieces, which fit together with grooves. To knock them in place, we put a block against the open side, then tap the block with a hammer. Striking it too hard, as Keith and I discover, damages the wood grooves. We scrap several pieces due to not-gentle-enough tapping, but our efficiency soon improves, and by late morning we’re like a seasoned railroad crew laying track. Justin and Frank handle the corners and odd-sized end pieces, sawing the slabs to the right size, while Keith and I handle the easy stuff.

“This is kind of fun,” I tell Keith as we crawl across the floor, tapping.

“Yeah—nice change of pace. And it’s good to be away from the Paint Nazi.”

I look up from all fours. “The Paint Nazi?”

“You know—Bruce. The guy who doesn’t do any work. All he does is stir paint. And he keeps barking out orders like he’s in charge.”

Bruce has indeed decreed himself the unofficial paint stirrer, probably because it’s the only job that requires extended sitting. He plants himself on a knee-high overturned white plastic bucket like it’s a throne. And now that I think about it, he is a bossy son of a bitch for someone with no authority.

“I guess he is kind of a paint Nazi,” I say.

“Oh yeah. He’s a paint Nazi. ‘No paint for you!’” says Keith, mimicking the famous Seinfeld episode.

The homeowner, Sherry, pops in to say hello. She and her dog live in a trailer in the front yard. Keith, Justin, Frank, and I are eating lunch in the shade on the cement back patio; she brings us each a cold Pepsi. Sherry was forced to evacuate her home after Katrina. She traveled to Texas, where her son is a priest. When she returned home, two months later, her house was ravaged by mold. She shows us photos.

“It was on the walls, the furniture—everything,” she says, handing us one dismal pic after another. “All the food in the refrigerator … mold. I didn’t have time to take anything out.”

It’s hard to imagine, given the newly painted walls, the new bathroom fixtures, the new lights, the new everything. In the photos the house seems infected with plague.

“The smell would about knock you over,” says Sherry. “I tried all sorts of cleaning stuff, but the only thing that got rid of it was gutting the house.”

Like Luther, Sherry believes Katrina was God’s will. A message. And being a devout Catholic, she sees another message in the photos.

“It got everything I own,” she says of the mold. “But there wasn’t a single bit of mold on my Jesus and Mary statues.”

By the end of the afternoon, we stand—me, Keith, Justin, and Frank—admiring our now-installed living room floor. It’s dark brown fake wood, and it looks damn good. I assume it’s not a big deal for Justin and Frank, since they’re contractors, but even they pull out cameras for a group shot. We pose in the empty room, proudly, like hunters with a deer.

As cleanup work begins, I grab a broom and sweep the adjacent dining room, which is empty but loaded with dust from its own new floor and lights, including a very modern, very sleek hanging lamp. I picture the dining room table that will soon be underneath; imagine Sherry and her family enjoying a well-deserved meal.

The floor is similar to one Julie and I recently had installed in our basement. We’d overhauled the room, and Dad helped me in the months before he died. I was determined to do most of the work myself—all the painting, installing new ceiling lights, replacing the outlets—but we bought new doors, one for the room and one for the closet. As usually happens with home improvement projects, we hit a snag: the new doors didn’t quite fit the new frames.

“We can replace that one door frame,” Dad said with confidence. “We’ll adjust the other one. I did it in California. It won’t be a problem.”

He did research, of course. Spent an afternoon at the bookstore reading about door frames. “Nothing is worth doing unless you’re gonna do it right,” he said, another of his favorite phrases. We installed the frame, and I thought it looked good, but Dad checked it with the level, and the frame was a thousandth of a degree off, so we fiddled with it again, and he grabbed the level again, and we fiddled with it some more until it was perfect.

Dad could fix and build anything, just as his father could fix and build anything. (The handyman gene seems to be missing from my DNA.) As a kid, he took apart and rebuilt old tractor engines on the farms where my grandfather worked. After high school, he earned his certificate for a National Radio Institute correspondence course in electronics (sample question on the first quiz: “If a full-wave rectifier is used in a 25-cycle circuit, how many pulses will there be per second in the output?”). Soon he was assembling circuit boards for minimum wage, and eventually moved to a small start-up, building check-processing machines for banks. From there he worked his way up to management and then medical electronics, overseeing the production of ultrasound units and MRIs.

I can barely change the wiper blades on my car.

The mechanical miracles that most impressed me were his least sophisticated work. As a kid I had a bunch of superhero action figures—from Aquaman to Spider-Man—all with removable polyester tights, all anatomically incorrect. Their limbs were connected to their torsos by a nylon band, and inevitably, after overuse, the band would break, and Superman would go from Man of Steel to Pile of Body Parts. I had a shoe box that resembled a superhero trauma unit, filled with naked limbs and masked faces. Dad would repair them, rebuilding the bodies with rubber bands and paper clips, making each hero whole again. Superman still survives in my closet, and he’s still in one piece.

And so I’m thinking about dismembered superheroes as I sweep near the stunning new lamp, which hangs from the fresh white ceiling. And I’m feeling so very, very proud of this newly installed floor.

Which is when it happens. How it happens, I’m not sure. Meaning I’m not sure how the lamp goes from hanging to not hanging. I know, as I am so vigorously sweeping, that the top of my broom handle whacks the hanging lamp. And the lamp becomes dislodged. And that its descent seems to take hours.

Imagine a small nuclear weapon implanted in a lamp. That’s how it sounds when it hits the beautiful new laminate floor. Every other sound in the house—the banter and last-minute work, the dumping of tools in toolboxes—stops. Total, terrible, mortifying, I’m-a-complete-jackass silence. Volunteers and Rebuilding Together staff rush to see what happened. And I stand with my broom, chunks of glass at my feet, feeling so … unskilled.

I’ll pay for the lamp, I tell Brian, one of the Rebuilding Together staffers. No, no, he says—these things happen. Keith helps me clean, and says the lamp shouldn’t have been installed yet with so much work going on. He’s right, I suppose, but as I look down at the chunks of broken glass, this doesn’t feel right. I pick up the big pieces, dropping them into an empty paint bucket, then sweep the tiny ones in a sparkling pile, wishing I could fix the lamp the way that Dad used to fix Spider-Man.

Given how much I’m sweating, my work shorts are developing a gym locker funk. I could wash them in the hotel washing machine, but that seems like a waste of water, so before dinner I shower with my shorts on, scrubbing them with shampoo as I bathe. Washing proves easier than drying, alas: the shorts are dripping as I blast them with a hair dryer over the tub.

So now I’m feeding dollar bills into the clothes dryer near the soda machines. As the dryer hums, I call Julie on my cell phone. She thinks I’m cracking up. She hasn’t said that, but I’m convinced that’s what she’s thinking, since over the last few weeks she’s seen me: 1) become surly over the joyous birth of our nephew; 2) engage in an uncontrollable late-night crying fit; 3) withdraw even more than usual after the aforementioned late-night crying fit; and 4) abandon her for a week in New Orleans to do work for which I’m unqualified.

Sixteen years ago—about a year before our wedding—Julie volunteered for a medical mission in Haiti (a job for which she was qualified), working with a team of Virginia nurses and doctors. The two-story hospital looked more like a run-down garage than a medical facility, but the trip brought much-needed, highly skilled care to people who otherwise wouldn’t receive it. Typical for a medical person, her photos included not simply locals and landscapes, but also a twenty-pound tumor that looked like an uncooked turkey.

I hope we can remove whatever tumors are lurking in our marriage. Julie and I are similar in personality, which is the strength and weakness of our relationship. We’re both mellow. Easygoing. We’ve known each other almost thirty years, yet we’ve never once fought. Which isn’t healthy. Because rather than tell her what I’m feeling—I understand why you don’t want children but I’m pissed and I’m sad and I’m lost and I’m trying to compensate for the void—I become more distant, more locked in my thoughts. And she doesn’t say, Snap out of it, you secretive, self-absorbed, self-pitying jerk. Your life is good. And so the bad feelings rankle.

The conversation is awkward. I ask her what’s happening at home. Nothing much. She walked the dog. She’s trying to find something for dinner.

I used to make her laugh, I think. I can’t think of a way to make her laugh.

She tells me a few work-related tidbits. I tell her about New Orleans.

“Well … I miss you,” I finally say.

“I miss you, too.”

I think about it, and I wonder if she misses me, or the me she fell in love with.

Each morning starts with a boxed breakfast, which includes a bottle of orange juice and three snacks: a pastry, a pastry, and—for the main course—a pastry. “A carton of carbs,” as Anna calls it. The question is what to eat first. Should I start with a pastry and save the pastries, or save the pastries and devour the pastry?

Actually, the pastries are tasty: one oozes with cherry filling, another is more from the muffin family. We eat them, half awake, at tables in the hotel lobby. Anna notes that some of the insulin-challenged Maltas have retreated to the restaurant for meals that won’t send them into diabetic shock.

When it’s time to leave for work, the bus travels a different route, stopping first in Gentilly, a neighborhood bordering the breached London Avenue Canal. This is ground zero of the flooding, one of the hardest-hit areas. We’re brought here, I assume, to satisfy the disaster voyeurism we all feel. (Bus tours take gawking tourists to the worst-hit locations.) But we’re also brought here so we’ll share what we see; so we’ll go home and tell our friends that we can’t forget New Orleans, because it’s even worse than they think.

We clamber off the bus. It feels like a Star Trek scene; like we’re the lone life-forms on an alien planet, observers of vacant streets and a vacant civilization. The neighborhood, Mark says, was blasted with a wall of water when the levees broke. The canal is about forty or fifty feet away. On many of the one-story homes, the waterline is just below the roof, near the gutter, meaning the homes were completely submerged.

“Most people had already evacuated,” says Mark. “But if you were here, you were dead.”

Owners’ cell phone numbers are spray-painted on garage doors. Other messages are from inspectors: “Natural gas leak” or “One dog rescued” with a phone number. Windows are missing. We pass a home with two boards nailed in a crooked X across the doorless front entryway. “Keep out!!!” is scrawled against one board, as if anyone would be tempted to go in. The same message is on a board across the bay window and its black-stained white curtains. The front yard, like every front yard, is covered with sand and sediment, the odd weed shooting through.

A muddy stroller lies on its side in front of a gutted home. A mangy teddy bear is sprawled atop a pile of trash. Many of these homes, says Mark, will be demolished. They’re structurally unsound. Beyond saving.

Construction crews work on the canal walls, the arms of cranes rising behind empty houses. I see what looks like a metal Band-Aid patch on the canal wall. I wonder if it’s strong enough to survive another Katrina.

We walk to a battered single-level home. Multiple watermarks stain the siding, like rings in a cut tree. The windows and doors are gone. Three tires lie scattered in the middle of the sandy front yard, not far from a white four-door car, the roof and hood crumpled, rust devouring the hubcaps. On the driver’s side door, painted in yellow like graffiti, are the letters DB. I ask Mark what it means.

“Dead body,” he tells me.

We stare for a while, and then we file back on the bus.

My mother says she dreams about Dad almost every night. She felt his presence in the bedroom one morning when she woke up. I’ve dreamed about him periodically since his sudden death: in each dream we’re driving somewhere, or watching TV—something ordinary—and then I remember … he shouldn’t be here. I struggle to figure out why he’s here, and how he’s here. Sometimes I wake up, thinking it’s real, until my half-awake brain says, Wait, hang on, no—he’s gone.

In one dream we’re at my grandparents’ old ground-floor apartment in Arlington. We’re in the tiny kitchen—me, Dad, my grandparents—sitting at the round table where I’d eat grilled cheese sandwiches as a boy. We’re laughing. I’m so thrilled to see them; my grandparents have been dead for almost thirty years. And then I’m quiet, because I know this can’t be. And then they become quiet. We sit in silence.

In my past nocturnal encounters with Dad, we haven’t talked. But this time I look at him, and with all the seriousness I can muster, I ask a single question.

What is it like?

I mean death. But I also mean, what is it like to know the answers: to know the age-old questions of why the hell we’re here, and what we’re supposed to do with ourselves, and how to live a meaningful life.

I look up at Dad as if I’m a child again. He smiles softly, sympathetically.

“I can’t tell you,” he says.

I’d like to take a moment to formally apologize to the Paint Nazi.

I’m sorry.

I’m sorry for saying that you’re bossy and that you spend the day on your tuchis stirring paint. Hey—who am I to judge? Because you, Paint Nazi, blessed our tired red team bus with a grand humanitarian gesture, a gesture that may not seem that grand to you but was exceedingly grand to me.

Here’s the scene:

At the end of another dirty day of sanding and painting and lugging supplies in the thick New Orleans heat, we wait on the bus for the last few red team volunteers before driving back to the hotel. My white Malta shirt is soaked, and I can’t tell if I’m smelling me or Antonio or some unpleasant combination of both. That’s when the Paint Nazi comes on board, holding two silver briefcase-sized boxes.

A cheer erupts. Beer! Frosty beer!

“Hey, all right!” says Antonio, applauding. The Paint Nazi rips the top off the first box and pulls out beer cans one by one, like an alcoholic Santa reaching into his perforated sack. The cans travel down the aisle, each so wonderfully sweaty and cold. I place mine against my forehead, rub it against my cheeks, and I smile at Antonio, and he smiles at me, and when I pop the top and gulp that first bubbly swig … after the heat and the sweat and the grime and hard work, this is the best beer of my life.

Okay, so buying beer doesn’t make the Paint Nazi the Paint Saint. And I won’t question how he found the time to not only sneak off and buy beer, but to find an open market in this largely deserted neighborhood. But it’s a thoughtful gesture, a nice morale boost, and far more than I’ve done for any of these volunteers. And so a toast to the Paint Nazi: may your paints be well stirred and your beer always cold.

At the end of the week, I hear the sound I will most associate with New Orleans. It’s not the hammering of nails or the whirring of drill bits through drywall, or a trumpeter’s wail in the French Quarter. It’s Antonio screaming.

We’re at a new site in the Ninth Ward. I’m one of several volunteers working on the back of the house, first putting on primer, then paint. It’s a two-story home, so I stand high on a ladder near the roof’s peak, awkwardly painting around a power line connected to the house. I can hear the cable buzzing. There’s no insulation, no protection, so the prospect of touching it and getting zapped with however many volts is real and a bit worrisome. Even more worrisome: getting zapped and falling twenty-five feet off a ladder. I would rather not die in a way that reminds witnesses of a Road Runner cartoon.

“It’s not worth it,” says Keith, who’s painting below and watching me stretch to extend my brush around the cable. “No one can tell if you miss a spot.”

He’s right. But I keep thinking of Dad’s favorite line—

Nothing is worth doing unless you’re gonna do it right.

And so I keep straining. As I listen to the hum of the cables, I wonder if there’s a secondary clause to Dad’s statement—

Nothing is worth doing unless you’re gonna do it right, or unless you’re going to get electrocuted and fall twenty-five feet off a ladder.

I climb down, lug the ladder a bit closer to the cables, climb back up, then carefully paint around the power line connection. Dad, I hope, would be pleased.

After lunch, Antonio and I take a quick walk around the block. He delivers a few of our extra box lunches to workers at a house two doors down. The workers are gutting the place, and it’s our first exposure to the rancid, rank, putrescent smell of out-of-control mold. The only scent I can compare it to is horseshit. Except more intense. Like extra-strength horseshit. From a really big horse.

When we return, Antonio and I clean out trash that’s accumulated in the bedraggled side yard, the grass mangy and tall. We drop the small stuff in bags, drag the big stuff to the curb. The more trash we pull, the more we realize it’s the muddy remnants of people’s lives, carried here by the flood. A Playskool hammer. Assorted Tupperware containers and muddy cups. A black plastic ball from a kiddie bowling set.

Antonio rakes some of the trash out of tall, unruly weeds near the fence.

Which is when he screams.

He sliced an artery. That’s my first thought. Or that he somehow impaled himself with the rake. The real reason for the scream isn’t quite so terrifying: he smacked a plastic bowl while raking. The bowl is filled with funky, slimy brown water; the water sprayed his arms and face. It surprised him, and it stunk, almost as bad as the horseshitty mold. I don’t blame him for screaming. To this day, Antonio won’t even call it water. He was hit, he says, by a “liquid substance.”

“I yelped like a little girl,” he says back in the hotel that night. “I thought it was urine or toxic waste or some kind of bacteria-infested gunk.”

But Antonio’s yelp wasn’t the cry of some trivial mishap, the whoooaaa you shout as you slip on ice or slam on brakes. This was a scream of terror. Like this “liquid substance” was a relic of the flood and the blood of the city’s twelve hundred dead; the human waste and industrial waste possibly lurking in this morbid stew; like death itself was creeping in the water. Which, maybe, it was.

A bit melodramatic, perhaps. Maybe the scale of the devastation finally got to us. But this I know: I’ll never forget the sound of that scream.

On our last workday, we help a family move back into their home. Most of the volunteers have left for the airport, so only a small group of stragglers remains. Antonio, Keith, Anna, and I ride in the back of a pickup driven by Brian, the Rebuilding Together guy. I take pictures as we cruise down Canal Street. Anna smiles beneath a baseball hat. Antonio flashes a peace sign.

Inside the house—a white shotgun home—Anna and I wipe the baseboards and walls, which are grungy from workers and work. Later, Antonio and I haul lingering trash to the street and load supplies in the truck to return to the warehouse: barrels of paint, brushes and rollers, assorted tools. When the moving truck arrives, we lug furniture and boxes inside. After Katrina, the family was displaced to Paris, Texas, and city residents donated this furniture.

“Really sweet furniture,” Anna says, admiring the large framed Florentine paintings, the overstuffed tan sofa and armchairs, the bright decorative pillows.

Antonio and I carry a couch up the driveway. He backs in through the front door with one end, I walk up the concrete steps holding the other. We move gingerly, trying not to drip sweat on the upholstery or nick the newly painted walls inside. Voices echo as boxes and box springs, tables and chairs, mattresses and knick-knacks stream into the house; as volunteer contractors install a new toilet and sink.

As we move this family into their rebuilt home, my mom, back in Virginia, is sorting through Dad’s things: sifting through closets and drawers, reviewing the objects of a life. The clothes were difficult. What if he comes back? If he comes back he’ll need his clothes. She knows it’s illogical, yet the clothes remain in the closet.

In a junk drawer of papers and coins, right below his sock drawer, she finds a six-page letter Dad had started, then stashed, six years earlier. She’ll find several letters like this: monologues from long flights to Tokyo or when Mom was in Virginia visiting the grandkids. He’d jot down his thoughts, his feelings, then tuck them away. I never considered Dad a religious man—he seemed more interested in science than spirituality—but in his letter he invokes God and envisions his sudden death.

My dear family,

I always fear that someday the Lord will suddenly call for me and I will not have told you how much I love you. I guess I worry because that is exactly what happened with my own mother and father. So, I love all of you so much. I often pray to the Lord to let me carry your burdens, give you good health, and happiness. I also ask Him to allow you the opportunity to use your talents for the good of the world. All I ask of you is to be your best and do your best. Always look at the other side—often you don’t fully understand things unless you put yourself in the other person’s shoes.

I tried to do my best here in New Orleans, though I’m under no delusions that our red and blue teams contributed much in five short days. What New Orleans needed after Katrina was a bayou Marshall Plan. What it got instead, largely, was people like me and Anna and Antonio. Eager volunteers with noble intentions. But the solution is inadequate for the problem, as inadequate as the flood-walls against Katrina’s waves.

Our greatest contribution is simply being here, spending money, seeing the problems, showing that people care. The day I scraped paint, sweating in the humid heat and wondering if my efforts really mattered, I told myself this: If someone doesn’t scrape, the house doesn’t get painted. If the house doesn’t get painted, the house doesn’t get finished. If the house doesn’t get finished, the owner doesn’t move back in. If the owner doesn’t move back in, he or she is still homeless—and Rebuilding Together can’t proceed to a new project.

I always fear that someday the Lord will suddenly call for me.

I often pray to the Lord to let me carry your burdens.

On the day Dad died, I was at my sister’s house when the hospital called.

We can’t keep the body, a woman told me. Where should the body go?

All day: questions. About an autopsy. Casket. Death notice. Burial plot. And then another call.

“Do you want to donate your father’s organs,” a hospital administrator asked. “We need to know.”

I lowered the phone to my chest.

“Who is it,” Mom asked from my sister’s kitchen table.

“The hospital. They want to know about Dad’s organs.”

She started crying.

“I can’t deal with that,” she said, shaking her head. “I can’t deal with that.”

“I’ll call you back,” I told the administrator.

I never did. And I’ve always regretted it. I wish we had created something good from something bad. That’s what I hoped to do here in New Orleans: channel grief into action. Worthy action. As simple as lugging trash.

All I ask of you is to be your best and do your best.

Use your talents for the good of the world.

I land in D.C. the next day and throw my bag in the backseat of Julie’s car. We kiss. She asks about the trip, and I tell her I painted ceilings and helped install a floor (I don’t tell her I shattered a lamp). I’m glad I went, I say. I’m glad I offered my labor and limited skills to three resilient families, because it’s impossible to walk the Lower Ninth Ward’s barren neighborhoods, to see the spray-painted rants and muddy scars, and not feel changed. To not feel humbled, and angry, and baffled, and sad.

We drive home, a route we’ve taken many times before. I’m not sure what’s next. Sometimes, in life, you can drive a familiar road and still not know where you’re going.