![]()

TEACHING ENGLISH—AND LEARNING ABOUT LIFE—AT

ESCUELA CUESTILLAS.

A BREEZE TICKLES SCRUFFY grass, the turf tough from soccer games and small feet. Palm trees and fruit trees shade tin roofs. It’s our first day teaching English at Escuela Cuestillas, an elementary school in rural Costa Rica, and Julie and I are screwed, so very, very screwed, though we don’t know it yet as we walk from the gravel road to a one-level building, home to six rooms and 110 students, most from low-income families, many of them Nicaraguan immigrants.

Children in uniforms—short-sleeve white dress shirts, blue pants—descend on us as we walk: they are whispering, giggling, inspecting the gringos. We’re escorted into the center classroom by Maria, the local program director for Cross-Cultural Solutions (CCS), our volunteer organization. The cinder-block school seems tidy and well kept, though this particular room is like a long-neglected garage. A discarded couch and dinged-up file cabinets are stashed against the walls. The chalkboard has a large, scablike hole. Centered above it is a gold-framed painting of Jesus and what I assume is God—white beard, flowing robes, air of confidence—though neither is identified, not that identification is necessary: Roman Catholicism is Costa Rica’s official religion.

Grinning children, third graders (I think), sit in groups of three and four, fidgeting and snickering behind benchlike desks, staring at us with tiny, curious eyes. Maria introduces us in Spanish. We stand in the humid room, already sweating—I have no clue what she’s telling them—and I wonder … where, exactly, is the teacher we’re assisting?

The kids pull pencils and papers from backpacks; we talk with them as best we can given our very limited Spanish. Maria hangs with us a bit, then wishes us luck. We watch her walk back to the waiting van. We watch the van turn around, dust rising behind it. And that’s when we realize it. We are the teachers.

We gaze at each other, Julie and I, just for an instant—there’s too much noise and too many boisterous children—but our thoughts are the same.

We are so, so screwed.

Over the next two weeks, as we scramble to develop multiple lesson plans for multiple classes, as we learn new Spanish phrases for high-energy children (Por favor, siéntense—“Sit down, please”), as we struggle to ensure that we don’t make their limited English worse, I’ll think back to the day we arrived, to a young woman we met at the airport. She was a fellow volunteer, overweight, frizzy-haired, no more than twenty years old; so uncomfortable she stood out, though wanting only to blend in. About twenty volunteers arrived the same day, and we congregated on a busy sidewalk outside the terminal in the capital city of San José, chatting, introducing ourselves, ignoring the calls of taxi drivers, waiting for other volunteers to land before riding to Ciudad Quesada, the town where we’re staying.

The young woman stood with crossed arms across her big belly, rubbing her left elbow with her right hand, a sad, scared look that said—

Oh shit oh shit oh shit—I’ve made a HUGE mistake—oh shit oh shit…

Maybe it was the two-hour tummy-churning, winding van ride over swooping green hills, through rusted-tin and stray-dog towns. Maybe it was the afternoon downpour, which lingered into a soggy, sloggy night. Maybe it was the skinny, bubbly college-age women who fill the dormlike home where we’ll stay. But the next morning, after hours of traveling—flying from the U.S. to Costa Rica, waiting at the airport, driving to Ciudad Quesada—the overweight girl with the overwhelmed look was gone. On her way back to the airport. On her way back home. Before any of us had eaten breakfast. She spent more time traveling to the town than she spent in the town.

On more than one occasion, when Julie and I are at the school, I’ll wonder if she was the smartest one of us all.

I can’t tell Julie that coming here was a mistake, because coming here was my idea. Julie knew from her medical stint in Haiti how exhausting these gigs can be. But I cheerfully spouted info from the CCS website: We’ll only work in the mornings! We’ll have our afternoons free! We’ll be good people!

Unlike Julie, who’ll work here for two weeks and then immediately return to her job, I’m off for six weeks. Around the time I went to New Orleans, my employer introduced a “renewal” program: after seven years of service to the organization you can take a four-week leave, fully paid, and add up to two weeks of vacation time. Given my new I-could-die-instantly-like-Dad approach to life, I signed up fast, determined to do something meaningful, though never believing I’d embarked on some larger quest. I certainly didn’t return from New Orleans three months earlier and think—

I’ve got it! I’ll be a daring do-gooder spreading happy fairy dust on every place I visit…

But I was formulating an idea that maybe, as a man without children—if that indeed is my destiny—I should use my time for activities other than reading the sports page and watching South Park. Both of which are happy pursuits, just not the achievements you want in your eulogy (“And so we remember Ken as a man who watched a lot of television …”). Plus … Julie and I need this trip. Travel is our spark. We rediscover one another away from home, where I sometimes fear we live separate lives. She takes classes, goes on dog walks with her sister and our infant nephew; I drift deeper into my what-am-I-doing-with-myself cocoon.

“It’s like you’re in your own world,” she once told me, “and I’m not invited in.”

We were so close in the months after Dad’s death. As close as we’ve ever been. And now … distance. Distance I’ve created. Distance from loving my life with her and hating the life I’ll never have.

The CCS house, alas, is unlikely to reignite passion. Julie and I are sleeping in bunk beds. Bunk beds are cool if you’re four, ridiculous if you’re forty, which is why no steamy romance novel has ever included the line Descend the little ladder to the bottom bunk so I may ravish you.

Our room is the size of a walk-in closet, with just enough space for the bunk bed, a few shelves, and a floor fan. I can stand in the middle of the room, extend my arms, and touch two of the walls, though I’m not complaining—we’re thrilled to have a room to ourselves. The house is overloaded with people, this being August, a peak time for college student volunteers. (Right now: around fifty volunteers. In two weeks: fourteen volunteers.)

After a blast of Costa Rican coffee and an energizing breakfast—fresh rolls, scrambled eggs, local pineapple so good it’ll make you cry—we take a first-morning stroll through town. Ciudad Quesada is not a destination; it’s a launching point for destinations more interesting than Ciudad Quesada. The town has everything you need—clothing, appliances, groceries—but outside of the sweet fresh-bread smell of the panaderías (bakeries) and the shady green square in the center of town, Ciudad Quesada is more functional than charming. Which is not to say I don’t grow fond of it. The people are friendly. Sunsets flare pink and red behind green mountains. The nearby land is rich with streams and cattle-filled pastures. Visitors do not outnumber the thirty-five thousand residents. I never see any Americans or Europeans other than CCS volunteers (locals call the CCS house “the gringo house”).

That afternoon we attend a mandatory orientation led by Juan, CCS’s country director. He explains the program’s rules. Everyone washes and dries their own dishes after meals. Volunteers are forbidden to drink alcohol in Ciudad Quesada, not even wine: CCS doesn’t want its local image tarnished by drunken, barfing foreigners. You get caught with a joint, a beer, a shot, probably even NyQuil—you’re gone. (After Julie and I return home, one long-term volunteer—I’m convinced he’s a fugitive hiding from the FBI—is kicked out for smoking pot and, oddly enough, for wearing another volunteer’s clothes.)

So this trip isn’t for the room service, cocktails-with-little-umbrellas crowd. Personally, I like the spare accommodations. This is what I wanted in New Orleans. “Most people come to Costa Rica, they never see the real country,” says Juan. “They leave their air-conditioned plane, they get on an air-conditioned bus, they go to an air-conditioned resort.” Not us. We will eat like locals, work like locals, and—the worrisome part—try to teach the local children.

After discovering that we’re the teachers, which is like some schmuck who can make toast suddenly running a restaurant, the first hour of our first day goes surprisingly well. We review the alphabet, numbers, nouns; I hold up flash cards with one group and they shout the words with gusto.

Blue card—Blue!!

Green card—Green!!

Brown card—Red!!—Green!!—Blue!!—Uhhhh…

We’re assessing their English skills. They can count, as high as one hundred in some cases, and they know basic nouns, but they don’t know verbs, so they can’t string words into sentences. They have English workbooks, though we never use them—one workbook will be nearly completed and another barely used, so we’re not sure where to start—which is unfortunate since we quickly exhaust our limited bag of teacher tricks.

“Let’s have them write their names on the board,” says Julie, resorting to educational improv.

Yes—perfect. We teach them “My name is” and they write with chalk—

My name is Enrique

My name is Tabitha

My name is Carlos…

Which kills about ten minutes.

Shit.

“Maybe they can write their birthdays,” I say.

They do that as well. Our blackboard activities work okay at first, but then one child wants to play tic-tac-toe, which leads to sudden swarms of children drawing tic-tac-toe grids. I play multiple games at once. Bend down and write an X. Straighten up and write an O. Turn right and write an X. As Julie says later, “We need more structured activities—otherwise they’re gonna run us over.”

By the end of the morning, a few scary facts are apparent:

Scary Fact #1

Because we’ll be teaching three different age groups, we’ll need to develop three different lesson plans. What works for second graders—say, drawing pictures—won’t work for sixth graders.

Scary Fact #2

No one at the school speaks English. Not the principal, not the other teachers. So we can’t ask for help. We can’t ask for insights. We can’t ask for mercy.

Scary Fact #3

Our class isn’t really a class. It’s more like an English club—and a forty-minute quasi break. Some students attend every day. Some pop in and out. It’s chaos.

Scary Fact #4

We have no idea what we’re doing.

At the end of the morning, as the children leave for lunch, a little sandy-blond girl with pigtails walks up and hugs me around my leg. She smiles and waves, clutching the backpack that fits snug against her tiny back as she skips out the door. And then another girl hugs me. And another one. Julie gets hugs as well. Well, at least they like us.

I find it surreal that I’m suddenly a teacher, given that twenty years earlier I was kicked out of college. Suspended, actually. For nine months. It was George Mason University’s way of saying, “You should take some time off and really reflect on what a dipshit you are.”

The suspension was one of the few things in life I’d actually earned, because attaining a 1.91 GPA requires a level of laziness and indifference that most responsible people lack. Some students graduate magna cum laude; I was magna cum quat: a pathological procrastinator who never studied and rarely attended class. As a sophomore, I tried to learn an entire semester of accounting ten hours before the final exam (which would be my entire grade since I hadn’t attended class in three months). Around midnight, after channel surfing for, oh, two hours, I downed some NoDoz and a few cans of Mountain Dew, opened the fat red textbook for the first time in months, and said to myself—out loud—in a pep-talk tone, “Okay—it’s time to learn accounting.”

About 5:30 a.m. I realized I was not going to learn accounting in time for the exam. It was the only thing I got right all day.

My lack of motivation would make more sense if I were a pothead or a crack addict (I’ve often thought of saying I was a crack addict because it sounds like a better explanation). But I was simply uninterested. As early as elementary school, a series of teachers made the same disappointed comment: “Kenny isn’t living up to his potential.”

All of which logically culminated in my suspension from college. And the worst part was knowing I had to call Dad. When he was twenty, he was a new husband, a new father, working two jobs to support his family, and taking his correspondence course at night.

You can do anything in life if you work hard enough. Dad said this repeatedly to me and my sister when we were young. I had twisted this—

You can fail at anything in life if you’re lazy enough.

I called him the next day. I was on the east coast, he was on the west. His secretary, Susie, answered the phone. “Bob Budd’s office …” If I was lucky he’d be in a meeting. A long meeting. I could leave a message with Susie: “Yeah—just tell him I’ve been suspended from college for nine months and I have no immediate plans.”

Please be in a meeting. Please, please, please.

“He’s here,” Susie chirped. “Hang on a minute.”

She transferred the call.

“Budo,” he said. “What’s up.”

“I have a problem,” I said.

He stayed silent as I explained, feebly, that I had attained consecutive “less than satisfactory” performances. That I was forbidden from enrolling for two academic periods. That my classes would be canceled for the spring semester, my parents’ money refunded. That the word suspended would be imprinted forever on my record like an academic cattle brand.

A weighty cross-country silence sat between us.

“Well,” he said finally. “What’s the next step?”

That was it. No lecture. Just … how we do move forward.

When Dad was a boy, his family moved constantly, uprooted when the rent came due, drifting through shabby homes and small Virginia towns. They moved from Delaplane to Middleburg, from Middleburg to The Plains, from The Plains to Marshall, from Marshall to The Plains—all in one year. He was quiet, shy from the moves, hiding when family visited, eating his dinner outside.

At the age of seven, he attended seven different schools in one year. Imagine always being the new kid, always ahead or behind the class. It could make you angry, or bored, or defiant, but Dad always swore it made him strong. On the day I told him about my suspension, it was never clearer to me: He was strong. I was weak. I was a fuckup. And I’d never really viewed myself that way.

After I was kicked out of college, I worked two jobs, including a sales gig at an electronics store. Selling batteries and widgets for minimum wage was a sobering experience, and though Julie and I hadn’t yet discussed marriage, it occurred to me that she might not want to spend the rest of her life with a widget salesman. Perhaps, I thought, while vacuuming the store’s worn carpet at closing time, a college degree might have its benefits. And so I went back to college. I graduated. And a few years later, I took night classes to get my master’s degree—earning straight A’s—mainly to prove I could do it. To prove I had just a whiff of my father’s fortitude.

Full from lunchtime beans and rice, motivated by fear, Julie and I walk to an Internet café in town and scan a kiddie-song website. Music, we’ve decided, is a fun, loud, active way to engage the children while teaching them English. So we scroll the online list, jotting down songs with potential. “Eensy, Weensy Spider.” “Old MacDonald.” “The Hokey Pokey.” Julie clicks on “If You’re Happy and You Know It.” We read the bubbly lyrics; she hums the impossible-to-forget tune.

If you’re happy and you know it clap your hands (clap clap)…

“It might be fun to teach it wrong,” I say.

If you’re crappy and you know it take a pill (gulp gulp)…

“You’re so helpful,” she says.

One song is a definite: “Head, Shoulders, Knees, and Toes.” First off, it’s easy—the lyrics to “Head, Shoulders, Knees, and Toes” are “Head, shoulders, knees, and toes”—and it involves movement (touching your head, shoulders, knees, and toes). Most of the kids already know the tune: it’s to international English classrooms what “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” is to baseball stadiums.

“Ooo—click on that one,” I say, pointing at the screen. It’s “On Top of Spaghetti,” one of my childhood favorites. Cheeses and sneezes, a mushed meatball that grows into a tree … this, to me, is poetry.

Julie sings a line softly, in a silly cartoonish voice.

The tree was all covered, all covered with moss…

I join her, quietly, to avoid the stares of the far-more-serious-looking Costa Rican Web users.

And on it grew meatballs, all covered with sauce.

That evening, back at the house, full from a rice-and-beans dinner, we’re still figuring out our lesson plans, sitting at one of the long cafeteria-style tables in the outdoor group dining area. A steady rain raps the roof. Julie has ideas: a word search puzzle, fill-in-the-blank phrases. Two other volunteers are working on plans as well, assisted by Hannah, a loud and lively forty-year-old Spanish teacher from New Jersey. We listen in—and beg her to help us when she’s done.

She sits across from us a few minutes later, asks about our classes, then churns out advice. “Make things active and funny,” she says. “Do either/or stuff. Point at one of the kids and say, ‘Is this a boy or a girl?’ ‘Is this a desk or a dog?’ ‘Is this a pencil or a house?’ And you’ve got songs, right? Good. Sing songs.” She looks at our list. “‘The Hokey Pokey.’ Perfect. Lets them move around. You could also give them cards with words on them and have them put the card on the object.”

It’s a ten-minute teaching tutorial that sparks ideas and boosts our shaky confidence. As I write down her suggestions, our new hero bemoans our situation.

“I don’t know why the fuck you got put in that class without any help,” she says. “I mean, you don’t even speak the same fucking language as the other teachers.”

The fucking amazing Hannah has entered our lives.

When I saw Hannah for the first time, wearing white sunglasses with rhinestones and demonstrating tae kwon do moves—Turn! Spin! Thrust! Kick!—I assumed I would not be spending a lot of time with this woman. She’s my opposite even more than Antonio was in New Orleans: four feet, eleven inches of raised-in-Queens toughness and relentless energy who never fails to shock with her jaw-dropping honesty about every intimacy in her loco life. In an atmosphere oozing with earthy PC earnestness, Hannah pines for her battery-operated boyfriend, shares every emotion in every moment—“I’m shvitzing from the fucking heat”—and drops f-bombs like a comedian at a Friars Club roast.

After the first-day orientation, Julie and I went for a quick swim at a nearby pool. Hannah joined us, as did Jonathan, another member of the very exclusive volunteers-over-the-age-of-forty club. Jonathan lives in Birmingham, England; he recently took a buyout after twenty-eight years as a communications officer for a bank. Coming here was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to tackle the unknown and help others—“I wanted to be selfless instead of selfish,” he told me. So he’s here for twelve weeks, away from his partner, William, who’s back home.

The four of us entered the cool water, wading more than swimming, laughing as Hannah told stories about her foulmouthed students, introducing us to teenage terms like snowballing. (Which, let’s just say, involves oral sex, and the transfer of certain bodily fluids from the giver to the receiver, and back to the giver.) Jonathan, already the droll counterpart to the talkative Hannah, recoiled in mock horror: “OH my God…”

We exited the pool, and a dripping little girl with a towel over her shoulders talked to Jonathan and Hannah, who are both fluent in Spanish. They erupted in laughter.

“She wants to know if we’re married,” Hannah said, giggling.

From that moment forth, Jonathan and Hannah were married. “Where is my husband,” Hannah says repeatedly. They become a unit, talking serious when alone, talking dirty when they’re with us; joking, hugging, quarreling, and insulting each other, often at the same time.

“I’d like to grow my hair longer, but I don’t want to look like a whore,” Hannah says one evening.

“You don’t need long hair to look like a whore, darling,” Jonathan replies.

“Fuck you, you fuck. You’re not my husband anymore.”

In our classroom hangs a banner made from a bedsheet, a project led by college students who taught here a few weeks before. “Never Give Up” is painted in Spanish and English, surrounded by the children’s handprints in yellow, blue, and red. The intent, I assume, was to inspire the kiddies, but to me it’s a cotton billboard trumpeting our inadequacies, since there’s no way in hell we’ll undertake something similar (although Julie encourages my “Always Give In” alternatives). Our goal, inspired by Hannah’s tutelage, is to offer fun but effective lessons—simple pub grub rather than flashy nouvelle cuisine. And the children seem to like what we’re serving, whether they’re supposed to be in our class or not (and we’re not always sure).

Our first class of students—we think they’re about eight years old—are eager and businesslike. Tabitha, a round-cheeked Nicaraguan girl, becomes one of our favorites. She’s always ready to laugh, like she just knows something funny is about to happen. After class she stays in the room, talking to us, giggling frequently. We can usually figure out what she’s saying, though in some cases, as with all the kids, I consult the English-Spanish dictionary, scrolling the page for the word.

Tabitha is smart. We ask the children to draw their families, and label them in English: mother, father, uncle, etc. A few children draw unlabeled stick figures. In Tabitha’s drawing the people are bigger, bolder, more defined. She labels everyone in English and Spanish. One morning she asks me my age—one of the few sentences I can quickly translate—and I make a frowny face, whisper my age in her ear, then hobble about like a geezer with a cane. She laughs, shakes her head no, walks to the board where Julie had written numbers and points at “30.”

See? Smart kid.

Tabitha and the other children play intense soccer games during breaks. “Teacher, teacher!” they yell, waving me to the field. I’m the goalie, presumably because they’d rather run and slide and knock the snot out of their classmates than stand and defend the goal. They play rougher than overprotective parents and teachers would allow back home. Not mean or vicious, just physical, running in sock feet, I assume to reduce kick-related bruises and broken bones. The boys unbutton their white uniform shirts and fling them in the grass, playing in their undershirts.

My goalie skills are roughly equivalent to my teaching skills, and a few shots zip past my long arms for goals. One comes from Adrian, a terrifically smart boy and gifted goal scorer. He’s the type of student—brains, athletic ability, good looks—about whom, even though he’s eight, I think: I should remember this kid’s name because someday he’s going to be Costa Rica’s first combination President/Soccer MVP/Astronaut/Movie Star/Nobel Prize Winner.

Adrian blasts a shot past my outstretched foot, and a little boy approaches as I retrieve the ball. I toss it to him, but he holds it, waiting as I walk. His Spanish is rapid, so I can’t understand, but I sense he’s suggesting a few improvements to my game, along the lines of “Listen—I realize you’re American, I know soccer isn’t your game, but dude, seriously—you have got to do better than this.”

I agree with whatever he’s saying, even though I don’t know what he’s saying.

“Sí, sí, sí,” I reply.

“When a player is dribbling toward you, don’t just stand here—charge him. Cut down the angle—make yourself big.”

“Ahhhhh—sí, sí, sí…”

He appears to be Nicaraguan. Many Nicaraguans migrated south to Costa Rica in the 1980s, escaping their war-battered country, searching for stability and prosperity, but finding poverty still hard to escape. Soccer goals, perhaps, are one thing he can control.

A community of Nicaraguan immigrants live in a nearby shantytown called Bajo de Meco. On a day when the schools are closed—Virgen de los Angeles Day, celebrating the country’s patron saint—Julie and I go with eleven other volunteers to play with the kids. Bajo de Meco is a rural dirt road village, each home a square hodgepodge of discarded plywood and rusted metal scraps. The CCS van chugs down a steep road, the mountains leafy and wet before us. As we squeeze out of the van, the children run to us, smiling and squealing. We walk to a dirt square, a former trash dump recently cleared of brush and debris by CCS. Julie notices occasional bits of broken glass.

The square is now a makeshift playground, blessed with the shade of a few tall trees. Andrew, a CCS staffer, unloads a burlap bag of outdoor toys. The result is semi-organized mayhem: a dodgeball game intersects a soccer game; the soccer ball zips past kids on a tree swing; the swinging kids nearly nail the soccer players. Tennis balls whiz by kids and volunteers playing pattycake. Remarkably, collisions are few.

I throw a football with a shirtless boy named Julio. We imitate each other—when I throw it high, he throws it high—and we’re soon sucked into the vortex of games, Julio switching to soccer, me moving to baseball. Julio’s sister, who insists we call her Chicken Little, rests a plastic bat against her shoulder, surveying her would-be players and then deciding, like a manager plotting strategy, that instead of Chicken Little we should call her Garfield. Satisfied with her irreverence—which seems to interest her more than baseball—she names me Rambo.

Garfield organizes a system. I, Rambo, am the pitcher. Heather, an eighteen-year-old from Oregon whom Garfield dubs “Cheemah,” is the catcher. The kids each get five at-bats, and when they’re not swinging they’re fielding, which is helpful, because a tennis ball smacked into tropical brush is hard to find, especially when your brush-clearing machete is a plastic bat.

After pitching for two hours to seemingly every child in Central America, I join Julie, who’s been playing dodgeball, for a neighborhood tour with some of the volunteers. A few children join us, kindergarten age, holding our hands as we walk past puddles in the pocked dirt road. The neighborhood has no electricity. No running water. The patched-together houses cling to green hillsides on wood supports.

The poverty rate in Costa Rica, Andrew tells us, is under 20 percent, which is pretty good compared to its neighbors (in Nicaragua it’s 48 percent). Costa Rica is essentially the Switzerland of Central America: the military was abolished after a coup in 1949, allowing the government to invest in health care and education. Nicaraguans now make up about 20 percent of the country’s population, leading to increasing complaints about illegal immigrants. More than once we hear lighter-skinned Costa Ricans note, with a hint of matter-of-fact smugness, that Nicaraguans are darker.

The men of Bajo de Meco work mainly on nearby cattle and sugar farms. Because this particular land was useless for ranching or agriculture, squatters built shacks, and the landowner, a Señor Meco, Ciudad Quesada’s richest man, never got around to kicking them out. Drugs, alcohol, and prostitution are common, and in an unfortunate cycle, the children often grow up to repeat their parents’ lives. And yet as we walk, everyone smiles at us and nods. The children laugh. And as Julie notices, for a community with no electricity or water—and kids who get really dirty—the clothesline laundry is clean, the school shirts a sparkling white as they flap in the breeze.

In addition to Rambo, I gain another name in Costa Rica: Lord Kenneth of Fairfax. James, a thirty-four-year-old Brit who’s volunteering for twelve weeks, tells me that Kenneth is a fine English name. He dubs me a lord, which means, he says, I’ll need a country estate, a pipe, a hunting rifle, a tweed suit, and a manservant. Oh—and some “below-stairs staff,” as he calls them.

James served in the Royal Air Force, in logistics, for seven years, and he remains a loyal subject of the British Crown, reserving a nook in the CCS kitchen for brewing proper English tea. When Hannah prods him to speak “normal fucking English” like her, he’s royally defiant.

“The Queen’s English will always prevail! In every corner of the globe there is always a piece of England!”

I do my best to encourage him. After awarding himself the title “Lord Juan of San Carlos”—the region where we’re staying—he announces he’ll write a royal decree instructing all residents of the CCS house that they are now loyal servants of the Crown. And that any inappropriate acts from the common ranks will be punishable by public flogging in the square followed by forceful consumption of rice and beans.

James is Jonathan’s roommate, as well as his workmate: they work together two days a week at a recycling center run by local women, and three days in a class for troubled teens (where they wrap a condom over a cucumber while teaching sex ed). I assume they’re paired together because they’re English—they’d never met before arriving here—but apparently someone in CCS thought they were a couple. This bothers the heterosexual James less than Jonathan’s disinterest in him physically.

“Why don’t you fancy me?” says James.

“You’re just not my type.”

“You mean you don’t find me attractive?”

“I’m sure plenty of women find you attractive. You’re just not the type of man I fancy.”

James is recently divorced, and this is the perfect place to be single: he’s one of just three unattached heterosexual men among roughly forty-five college-age, earthily attractive single women. Over time, several women will offer to serve as short-term volunteers in the privacy of James’s room, if you know what I mean.

James is also a master of the word-guessing game Taboo, which we find on a shelf in the main area of the CCS house. If you’ve never played Taboo, one person holds a card with a word on it. That person—in this case James—helps other players guess the word without actually using the word, or five other related words on the card.

We warp the game so every word is sexual. Why this happened, I don’t recall, though I’m sure Hannah talked about missing Bob (her battery-operated boyfriend) and how much she interacts with Bob in a given week, and Jonathan said “OH my God …” and Hannah informed us that she and Bob are close because she hasn’t had sex in nine months, and Jonathan suggested that this perhaps led to a marked decrease in New Jersey’s venereal disease rate, and Hannah told Jonathan, “You are such a fucking asshole.”

“This is a movie title,” James announces, reading a Taboo card. “So this gent goes round to the pharmacy and buys some Viagra, because he’s meeting a woman that night. And things go well—they go out to dinner—and later on he gets lucky and takes a Viagra. But then, during sex, he has a heart attack. And he keels over, right there in the bed, right during the sex.”

We never guess the answer: Die Hard.

Our own perverted entertainment aside, CCS offers a variety of education sessions for volunteers, from Spanish classes to lectures on Costa Rican history to Wednesday afternoon field trips (including a visit to the Arenal volcano). As part of our cultural education, a woman who works at a nearby diner offers dance lessons. We fold up tables in the outdoor dining area to make room, and she winks and grins as she demonstrates salsa moves, her black hair bouncing, hips and shoulders shimmying to Latin boom-box music. As one of only two straight male participants—James is the other—I feel obligated to say that watching this woman dance is worth the expense of flying to Costa Rica.

About thirty of us stand behind her in five cramped rows. We’re supposed to start with feet apart—open—then bring them together, moving to the left. She shouts instructions as she dances—

Open center center TAP

Open center center TAP

She adds a spin move—

Center TURN center TURN

From my back row perch I watch our attempts to mimic her sultry moves, and I’m impressed by how truly, truly awful we are. We look like narcotized robots. And our outdoor dining space wasn’t designed for a large group to salsa dance: when we sashay to the right—I’m on the end of the back row—I run out of real estate well before we’re done center centering, and since I’m watching my feet I barrel into the wall with a thud.

Our sizzling salsa teacher is oblivious, her back to us, sliding to the left, then to the right, as if the dance gods created Latin music and tight Levi’s just for her. We’re all drenched in sweat—I was sweating before we even started—yet she’s pleasingly dry despite her long-sleeve sweater. We trudge behind her to the left, then lurch to the right.

Open center center TAP

Center TURN center TURN

It’s a ceramic tile floor, and a back corner tile is loose, with some sort of pipe underneath. When I drop my foot for the tap it makes a thwock noise, which complements the thud as I hit the wall.

Open center center THUD

Center THWOCK! center THWOCK!

James, already a reluctant participant, smartly leaves his row and takes a seat. “It’s like a bloody marching drill,” he says.

Our teacher finally turns and sees our zombie dance team, her face a mix of sorrow and shock. Like seeing a pack of dogs pee on your favorite flower bed.

Our dancing may suck, but Julie and I are performing somewhat better at the school. Julie created a word search puzzle by hand, focusing on verbs, which the students devoured. A few even find a mistake: the word read appears twice.

I enjoy watching Julie with Roberto. He’s a sweet, pudgy kid, not the brightest student at the school, but one of the friendliest. Roberto frequently lobbies Julie to play Go Fish with our deck of English-Spanish flash cards. The problem is that none of the cards match. And yet Julie still plays Go Fish with him, flipping through all sixty or so cards, appearing interested as Roberto holds up a picture of a fork.

“No,” says Julie, checking her cards. “I don’t have a fork. Do you have this?”

It’s a card with a chicken. Nope—Roberto doesn’t have a chicken.

Baseball?

No.

Umbrella?

No.

Clock?

No.

Because of our inadequate Spanish, she can’t say to him: Hey, Roberto—this is pointless. The cards DON’T MATCH.

Finally, mercifully, they sift through the entire stack. And then Roberto tugs Julie’s shirt and holds up the stack of cards. He wants to play again.

It’s been enlightening to see Julie—to see us—pulled from our usual roles like the shuffled cards; to observe the person I know best in a new environment. To see her creativity. Her patience. She’s so wonderful with children. Always has been. Watching her write and draw with the young girls, showing them how to make a cat’s cradle with yarn … at times like these our childless life is a mystery to me.

Many of the kids, particularly the girls, ask if Julie is mi esposa— my wife. I say yes, fan my face, sigh dreamily. The girls cup their hands over their mouths and giggle. One day, after class finishes, Tabitha speaks to me in Spanish. She’s asking, I think, if Julie and I have children. I grab a piece of chalk and draw male and female stick figures on the board. One is me and one is Julie. I draw a little kiddie stick figure next to us and point.

“¿Yo tengo?” I say.

I have?

She nods.

No, I say.

Tabitha thinks, then points at the chalkboard child. If we have a child, she says, and we have a girl, we could name her Tabitha.

Two days after national holiday number one is national holiday number two: Día de la Madre (“Mother’s Day”), the Feast of the Assumption. Millions of people, we’re told, walk to Cartago, east of San José, to see the apparition of the Virgin. With the schools closed again, we return to Bajo de Meco, Garfield waving as I squeeze my long legs out of the van. She again calls me Rambo, which leads to a chorus of greetings from the kids.

Hola Rambo!

Heyyyyy Rambo!

Rambo! Rambo! Rambo!

I spend most of my time playing baseball with a young boy. We play for close to two hours: I throw the tennis ball, he whacks it with a plastic bat. Over and over and over in the sticky heat, the ball slicing through mud puddles with each energetic swing. I’m pleased to say he gets tired first (I am Rambo, after all). He pats his stomach, runs to one of the patchwork shacks, and returns with a banana. I squat before him in the dirt road.

“¿Como se llama?” I ask.

“Rafael,” he says.

He asks me my name. I tell him. I want to tell him what a good athlete he is: he rarely missed a pitch.

“Tu juegas béisbol muy bien,” I say in my meager Spanish.

He beams. It almost catches me off guard—his grin and his puffed-out chest—though this is one of the reasons we’re here: to offer encouragement to those who rarely receive it. But somehow it seems so inadequate. I’ve never seen poverty this extreme. I suppose that’s why the shirts sparkle on the clothesline. The people own nothing else. When we pull our bag of sports equipment from the van, you can tell the kids are thinking, Holy shit … they have TENNIS BALLS. And yet by global shantytown standards, I’m sure this is quite nice. The Bel Air of shantytowns.

Later I ask Mauricio, the program director, why we went to Bajo de Meco. Sure, we brought some morning fun to the kids, but how is that helpful?

“These children have no idea why they’re there,” Mauricio explains. “They never saw the war that drove their parents away. They’ve never seen their country and they don’t know why they’ve been stigmatized for leaving there. They grow up feeling that they are not important; that it’s normal to be pushed away or ignored.

“In our society, especially in rural areas, the highest social status is a gringo. Americans are considered wealthy and knowledgeable—which makes them important. Sending volunteers to this neighborhood has an effect on the adults, the other people in the community, and the children. Those children deserve to see something different than what they know. They need to understand that another way of living is possible. When all they’ve seen is that neighborhood, no one can blame them for not aspiring to something better. But when they feel important, welcomed, and acknowledged by others—especially those they consider important—it enhances their self-esteem. And it’s a reminder to other community members—who know the gringos are visiting Bajo de Meco—that these children exist and they need someone to give them better opportunities.”

When we toured Bajo de Meco, a little barefoot girl showed off a pet parrot. Several of the residents own birds. Maria tells Julie they catch the birds in the forest, then clip their wings so they can’t fly away.

On Fridays after lunch, volunteers race out of the CCS house like soldiers with a weekend pass. It’s your big chance to leave town and see the country, so we hire a local driver and travel with Hannah, Jonathan, James, and six others in a van for a weekend jaunt to an isolated cloud forest town called Monteverde.

Sure, it’s a five-hour drive, but who cares! We’re free! We can drink a beer! We’re on an adventure! Woo hoo! And we sustain that merry mood for two laugh-filled hours until traffic stops on a narrow, twisty-turny rain forest mountain road.

We sit. Wide fern leaves press against the windows and roof. We sit some more. Marco, our driver, asks a few passersby what’s happening. Hannah translates. Workers are replacing drainage pipes in a stream, which means a single-lane earth bridge has been obliterated. Why they picked a Friday afternoon for such work, I’m not sure.

We exit the van to stretch. A steam shovel covers two new concrete pipes with dirt and rocks, moving boulders on both sides to support them, then leveling them out and packing them in. Pedestrians stand within a few feet of the dinosaur-like machine as it loads and unloads boulders. James and I watch, then get soaked by a sudden downpour. It’s the first time I’ve felt cool in a week.

After two long hours, the bridge is rebuilt. Traffic starts to move. Three hours to go. What we don’t realize is that of two possible routes to Monteverde, our driver has chosen the longer, more scenic, yet far more roundabout route around Lake Arenal, instead of the shorter, still fairly scenic, less roundabout bypass. So that adds to our travel time. As does temporarily getting lost.

We stop at a pizza joint in a tiny, bustling-because-it’s-Friday-night town, then embark on the most rugged stretch of the drive. The closer you get to Monteverde, the more ragged the roads become: a lunar-style mix of craters, gravel, and softball-sized rocks. For two hours we bump, bump, bump up the mountains, our rowdy banter silenced. Moods, and stomachs, turn sour. Heads bounce. James’s seat squeaks. Twilight becomes night, the headlights squinting through dust, and still we crawl up the rocky road. It’s like a two-hour earthquake on wheels.

Bump, bump, BUMP, bump…

Cindy, a twenty-six-year-old from England, announces that she really needs to pee. But Marco the driver doesn’t speak English, and Hannah and Jonathan don’t translate. Maybe they can’t hear given the creaks and squeaks of the bouncing van, the thumps and grinds of the tires over stones.

A queasy James lowers his head out the window.

“I really have to go to the toilet,” Cindy moans.

Bump, bump, BUMP, bump…

I begin to wonder if this is what hell is like: a never-ending claustrophobic ride in an old van with bad shocks on a bad road with a guy who might throw up and a woman who might have an accident, assuming that the van doesn’t have one first.

“I’ll go anywhere,” she begs. “I can’t hold on any longer.”

After forty-five minutes of pee pleas, we pull over. Women scramble through darkness and cloud forest mist to crouch behind bushes on the side of the pitted gravel road. The men are less worried about privacy.

We get back in the van. “These are worse than the roads in Haiti,” Julie says as we return to our now very familiar seats.

Bump, bump, BUMP, bump…

When we finally reach Monteverde, around midnight, we can’t find our inn. When we do find it, the inn is dark. It looks closed for the night. Jonathan gets out to check, but Hannah doesn’t like the looks of the place.

“No way—I’m not staying there.”

“Why not?” says Cindy, with a hint of testiness.

“It looks like a shithole.”

“Better a shithole than no place at all.”

A mild argument ensues. Hannah wants someplace nice, and she wants privacy since she’s been getting up at five in the fucking morning to avoid lines for the fucking shower, and she wants fucking space since she’s in a claustrophobic two-bunk-bed room with three fucking roommates, one of whom has an ever-present boyfriend.

“No one’s there,” says Jonathan, climbing back in the van.

We’re now faced with the terrifying prospect of sleeping in the van. Marco drives to see what else, if anything, is available. We find a hotel with lights on: El Sapo Dorado (The Golden Toad, named after Monteverde’s most famous, and now extinct, amphibian). A security guard is shutting down. Hannah and Jonathan beg him to show compassion. The guard calls the manager. A minute later and we’d have been out of luck.

We rent cottages, sleep, and dream sweet dreams about smooth pavement.

Monteverde’s primitive roads have one benefit: they discourage people from visiting Monteverde. Open a superhighway and the cloud forest would be packed with ecotourists. Already roughly a quarter million people a year endure the hemorrhoid-inducing trek to see its steep, biodiverse charms.

The weather is refreshingly cool, like a damp autumn day back home. We start at a zip-line park, whizzing like Spider-Man down cables at speeds approaching 45 miles per hour, soaring above the mist and the canopy. After that we swoop waaay into the air on a Tarzan swing. James screams from the speed and the height—around forty feet at its peaks—and from the tightness of the cables around his crotch.

“Ohhhhh my God!” he yells, approaching a block of trees.

“Augggghhhh—my bollocks!” he cries on the way back.

Hannah skips the Tarzan swing. She’s freaked out by the zip-lining heights, so she rides with—and on—one of the hunky staff members, strapping her legs around him, as ordered, making no effort to conceal her pleasure.

“You’re such a tart,” says Jonathan, the shafted husband.

“We’re divorced,” Hannah says, screaming as she and her new zip-line stud careen toward the next platform.

The night before we left for Monteverde, a nineteen-year-old female volunteer named Pat, who was supposed to join us on the trip, tried joking with Hannah after dinner. Several of the under-twenty Caucasian girls have never spoken with Hispanics, Europeans, African-Americans, Muslims, Jews, or basically anyone other than their fellow Christian-American white folks. I give them credit for traveling and exposing themselves to the world, but their ignorance can be startling. A tight-faced girl from Minnesota, who looks no more than eighteen and struggles to smile, either from piety or culture shock, asks Jonathan—

“Do you have cows in England?”

He’s too stunned to respond. The girl bites her lip.

“I just said something stupid, didn’t I.”

As for Pat, in her attempt to be funny, she nodded at Sarah, another sheltered student away from America for the first time, and said snarkily to Hannah, “Sarah has never seen a Jew before. Do you have a Star of David tattoo on your ass?”

Hannah’s eyes reddened. She raced from the outdoor dining area through the kitchen and up the wood stairs to her room. James decided the weekend chemistry would now be too volatile if Pat joined us in Monteverde. So he fibbed and told her we didn’t have room. And then he was pissed that he was the one who performed the dirty deed.

“Well,” I announced to Julie, “this is going to be a fun weekend.”

Ironically, I think Pat wanted to ingratiate herself to Hannah; to appeal to her tough-gal persona. And because of that tough-gal persona, I figured the sassy, in-your-face, martial arts maven Hannah would mush Pat’s nose with a foot to the face. So even though Pat’s comment was in poor taste—and particularly jarring in such a bastion of save-the-world political correctness—I’m surprised that Hannah was so devastated. Her showy strength, I suspect, masks a deep vulnerability.

Hannah has told us a little about her ex-husband. “The shit-head,” as she calls him. The marriage was short. He was domineering, dictating how he wanted her to dress, how she should wear her hair (one reason it’s now defiantly short). Our first morning in Costa Rica, when we wrote on a whiteboard why we were volunteering, Hannah wrote that she was here because she’d turned forty.

“I’ve never had a sweet sixteen or Bat Mitzvah and my wedding was small—I hate parties, I think they’re fucking idiotic, and I don’t like being the center of attention. So I thought I would give something back instead. It was the antidote to self-pity over my old age. But I wasn’t trying to find myself,” she says. “I am found.”

Though she no longer wears it, Hannah brought her wedding ring to Costa Rica. Late that evening, after a guided nighttime hike in the cloud forest and dinner at a local café, we all return to our cottages. But Hannah eventually goes outside. She takes a few steps in the darkness. And with the strength built from months of postmarriage, postdivorce tae kwon do, she hurls her wedding ring into the dark woods and the cloud forest fog.

On Monday, back at the school, I’m suffering a Monteverde hangover. Not from alcohol—though it was nice to down a few cold Imperials, the Budweiser of Costa Rica—but from a kick in the shin by an ill-tempered horse.

We took a guided horseback ride on Sunday along green mountain trails, passing weathered barns and lazy cattle, peering at small valley villages below. The only glitch was that James’s horse hated my horse. He snorted and squealed—the horse, not James, who instead screamed “Gaaaaaa!”—and then James’s horse, while attempting to kick my horse, kicked me instead. Hoof hitting bone, if you haven’t experienced it, is like getting whacked with a baseball bat. After that, James and I tried to keep our horses apart, but we aren’t exactly accomplished horsemen. So our horses still trotted close enough to neigh some pony profanity to one another, grunting and huffing and biting.

“He’s bloody crazy!” cried James.

“Just keep him away from me,” I said.

James’s horse bristled, then took off at a trot.

“Whoooaaa!” hollered James, bouncing on the saddle as his horse charged ahead.

The shot to the shin was pain number one. Later that day, on the van ride back to Ciudad Quesada, I suffered a muscle strain. While sitting. Julie and I were in the back of the van, and she graciously shared her iPod earbuds: she used the left bud, I used the right. We listened to a podcast of NPR’s Car Talk. I turned to grab a water bottle and—pop!—my back, right between my shoulder blades, erupted in pain that stretched to my neck. Julie thought it was a muscle spasm, though it felt like a pinched nerve. Either way, I’m clearly getting old: I’m hurting myself in the midst of inactivity.

The next morning I asked Julie for assistance from the bottom bunk.

“Can you help me?” I wheezed.

“With what?”

“With getting up.”

“Seriously?”

“I can’t do it on my own.”

At the school, the kids view me as a human jungle gym during breaks, grabbing my arms, climbing on my back, taking turns as I swing them in circles. Given my limited Spanish, saying “Sorry—teacher popped a back muscle listening to NPR” isn’t feasible, and I forgot to ask Hannah for a simple “I’m in pain” translation. So I endure the onslaught of exuberant little uniformed bodies, though it’s likely the children learn a few colorful new English words, the kind you won’t see on flash cards.

In our muggy classroom, we’re working with three new groups of kids, and our first two classes are impressive: the students are serious, smart, motivated. Two girls in class number one—Rachel and Roxana, best friends, both fourth graders—know enough English to translate our instructions. Rachel is a chubby, thoughtful, very bright girl who could whup some serious ass if provoked. When a few boys get loud during class, Rachel yells, “Silencio!” The boys are silent.

The second class, fifth graders, is even better. They enjoy using letter cards we’d found at the CCS house (like flash cards, with a different letter of the alphabet on each card). They spread the cards on the desk and spell words and phrases we suggest: animals, fruits, machines—anything we can think of. We adapt our lesson to their enthusiasm. Flexibility, we’ve learned, is essential.

Two classes, two gems! It’s like an educational Eden.

And then the first graders arrive. They run around the room, jump on the beat-up old couch, yell, hit each other—and it’s the boys more than the girls, of course, testosterone transforming males under six into spastic imps when in groups of three or more. They’re not bad kids, especially one on one. Timmy, one of our biggest couch bouncers, frequently shares his snacks with me and Julie, and escorts me by hand during a break one day to play foosball at a corner market. They’re just high energy and rambunctious. So rambunctious that by the middle of the week I scream in the classroom.

It’s a calculated scream, the result of strained patience. First off, I’m getting annoyed by the students’ blobs: sticky wads of goo that come as a prize in bags of chips. When you throw ’em, they stick to various surfaces. Typically before and after class, a blob will hit the chalkboard—bloop! And then a window—bloop! The older kids restrain themselves while we’re teaching, but with the first graders I hear the occasional bloop as the boys—always the boys—run, shriek, and pant.

Also, at least once a day, a soccer ball will bounce into the room, careening off the walls. We ask Hannah to translate this critical phrase for us: Tomen la pelota afuera (Take the ball outside). So I say Tomen la pelota afuera, but reading it in a stiff voice from a notepad wimpifies its impact. And even the first graders know I’m a short-timer, the equivalent of an international substitute teacher, and really, is there anybody with less authority in the world than a substitute teacher?

As Timmy and Luis, another high-energy boy, jump on the couch, I remember: during our first-day CCS orientation, Juan said that Costa Rica is a macho-male society. Indeed, the school’s principal, Señor Blanco, looks more like a rancher than an educator: short-sleeve plaid shirt tucked in jeans, tan skin, firm forearms that come from work rather than workouts. He has a gold tooth, for cryin’ out loud. So I decide:

I am bigger than these kids. I am stronger. They are used to a male-chauvinist, male-dominant society.

I will DOMINATE them with my manliness.

And then I use my deepest, meanest, nastiest, surliest, most pissed-off, ticked-off, bad-ass, Darth-Vader-in-a-shitty-mood voice, and I bellow—

HEY!

It’s like a verbal whip crack. They stop jumping. They look up at me, surprised. I pull them off the couch. I don’t hear any bloops. And within five to ten seconds of my ultramasculine, hairy-chested yell—I am a Costa Rican BRUTE—the boys are back on the couch, running and jumping.

But Consuela heard me yell. She is a tall, thick, imposing woman with gold hoop earrings and a demeanor that says, I am a good person but you do not want to mess with me. Her primary duties seem custodial—she kindly brings us bananitas during breaks—but she’s also the school’s mother-in-chief. Señor Blanco may be the principal, but Consuela is the boss. Now she looms in the doorway and snaps at Timmy and Luis, a torrent of unyielding machine-gun Spanish. They freeze, then sit meekly at the nearest desk. She utters what I assume is Español for “Don’t make me come back” and departs. The class is quiet.

Forget the salsa dancer. This is my new Costa Rican goddess.

Clearly Julie and I need to burn the first graders’ energy; to transform their kiddie vigor in a way that helps them learn. This seems a wiser strategy than me yelling. So we unveil our musical ditties, starting with “Head, Shoulders, Knees, and Toes.” As you sing you touch the body part mentioned in the song. We stand in a circle and with each chorus we speed it up, ultimately to ridiculous proportions—like calisthenics on amphetamines—which gets huge laughs. In fact, it’s so hilarious it increases their energy levels.

Julie and I laugh, too, though we’re thinking, Do these kids ever get tired? It’s time to blow their little minds. Julie and I now debut our secret musical weapon, a tune that’s totally new to Escuela Cuestillas: “The Hokey Pokey.”

The kids look intrigued. They follow our lead. We put our right hands in, we take our right hands out. We put our right hands in and shake them all about. We do the Hokey Pokey and we turn ourselves around. That’s what it’s all about.

In addition to right hands we do feet, elbows, shoulders, chins, hips, and—the ultimate in first-grade comedy—butts! You can’t go wrong with butt shaking if you’ve got the right crowd.

Maybe it’s the volume—the singing, the laughs—maybe it’s the novelty of the song, but as we’re hokeying and pokeying scores of older kids line up outside the windows to watch. Some smile. Some seem to wonder if we’re mental patients. But our energy-burning efforts are successful: Julie and I are exhausted.

“You know,” Hannah tells me later, when I describe the hyperactive first graders, “if you’re hoping to have kids, this was the last place you should have brought her.”

Stray dogs lounge on the sidewalks in Ciudad Quesada, sprawling on shaded concrete in front of side-street bakeries and shops; sleeping, licking their paws, licking their balls, hoping for a handout, though never seeming to beg. Much as Julie and I love dogs, we don’t approach them, partly because I don’t want to acquaint myself with diseases carried by stray Central American pups, partly because we don’t want them shadowing us through town. But they seem content, and they seem healthy, hanging with their doggie amigos. Lazy Costa Rican mutt doesn’t seem like a bad life.

I was supposed to watch my friend Adam’s two dogs the weekend Dad died. Adam and his family were on vacation. I’d let the dogs out that morning—Holly, their Lab, is a compulsive Frisbee catcher—and when I called Adam from the hospital parking lot I apologized, because dog walking was now low on the postdeath to-do list. And yet I felt bad for shirking my pooch duty. I apologized several times: I’m sorry about the dogs … Maybe it was the shock. I felt the same concern about our Father’s Day dinner reservations for that night. I was semi-obsessed with calling the restaurant to cancel.

“Don’t worry about the dogs,” said Adam. “Jesus. I can’t believe this. Are you okay?”

Yes. No. I don’t know. I apologized again.

I read recently that Americans spend over $40 billion each year on their pets. Costa Rica’s gross domestic product, by comparison, is roughly $20 billion. In the pet biz, pampered pooches are often called “fur babies”: a much-coddled substitute for a child. Which is what childless people like Julie and I have. A fur baby.

I love our dog, Molly (a shepherd-terrier mix, we were told, though who knows what breeds are racing through her bloodstream). She’s nine now, and though gray streaks her cheeks and floppy ears, she still loves a long walk in the woods or to chase a squirrel she’ll never catch.

I was walking Molly one day when I met another dog walker, a woman Julie must chat with while plucking poo from the grass. “Ohhh,” she cooed to Molly in a baby-talk voice, as the dogs sniffed each other’s anuses. “Your mommy isn’t with you today!”

Her mommy? Julie is not Molly’s mommy. Molly’s mommy had floppy ears and paws and upwards of eight nipples.

I have no problem with viewing your dog as a fur baby. But Molly is my pal, not my child. We hang out together, we walk together, we tolerate each other’s farts. No matter how lousy my day might be, she scurries to the door when I come home and wags her tail as if nothing makes her happier. But I will not hear her first words. I won’t help her with her homework. I won’t cheer her when she gets an A and chastise her for an F. I won’t console her when she breaks up with her first love even though I’m thrilled because the guy was a chump. I will not watch her graduate, grow, suffer, succeed. A dog is a dog. A baby is a baby. I have a dog.

Rice and beans are a staple of the Costa Rican diet, so we’re served rice and beans at breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Overall the food is tasty—strips of sautéed chicken mixed with fresh tomatoes, onions, or peppers; fried fish with thick mashed potatoes for lunch on Fridays—but I admit it: I’m tired of rice and beans. It’s the repetition. If someone scheduled an orgasm three times a day you’d eventually say: “I am so sick of orgasms. Can we have pizza instead of an orgasm?”

As part of our evening pre-dinner routine, Hannah asks me with a straight face—

“Do you think we’ll have rice and beans tonight?”

“Hmmm—I hope so,” I say. “That would be nice.”

By the second week we make snack runs. I head with James and Cindy to a market up the hill on the main street, where we buy sodas and chips and cookies. Dessert is a rarity at the house—we have cake when it’s someone’s birthday—so one evening we walk to an ice cream shop. I’m enjoying my scoop of chocolate on a sugar cone when I spy a girl on the sidewalk who reminds me of Garfield: the girl from Bajo de Meco. I squint, look hard, and no, it’s not her, but I wonder—

Has Garfield ever had ice cream? Her home has no electricity, so there’s no refrigeration. Her family has little money, so ice cream would be a luxury. Garfield lives a rice-and-beans life, trapped in sameness. The monotony of poverty.

As melting chocolate ice cream streams over my fingers and down the cone, I wonder what I’ve been wondering since we arrived: what good are we actually doing here?

Think about the school: We’re there for two weeks. It took us half that time to figure out what we were doing, and what the kids know. Whoever follows us will go through the same process. So how much English are these kids learning?

CCS maintains you make a difference simply by showing up. In poorer parts of the world, parents are more likely to send their kids to school—instead of sending them to work—because American and European volunteers give a school cachet. Parents figure it must be worthwhile if foreigners are there. And you improve the image of Americans. A lot of Costa Ricans think that Americans are lazy, Mauricio tells us. The Americans they see on TV shows never work; they drink coffee and sleep around.

One night Hannah encourages us. “If these kids learn one word of English, if they see what normal Americans look like, you’ve made a contribution.” Maybe so. But I wonder.

Earlier that day at the school, Julie and I wrote seven fill-in-the-blank questions on the board:

What is your name?

My name is _______.

What is your favorite game?

My favorite game is _______.

What is your favorite animal?

My favorite animal is _______.

A boy named Carlos, probably about eight years old, writes “dog” in the space for animals, not surprising since he often pretends he’s a pooch. Many of the poorer families are led by mothers, so Mauricio had warned that some kids may call me “papa.” That never happens, though the grinning Carlos clings to me constantly. During a break after class, I talk with Principal Blanco, attempting to translate as he asks where Julie and I live and how long we’re staying in Costa Rica. Carlos is behind me, arms around my stomach, jumping up and down, barking into my back.

Maybe, as Mauricio hinted, Carlos attaches himself to me—literally—because his father abandoned his family. So is my being here confusing to a kid like this? Am I just another father figure who can’t be trusted?

In another of Dad’s secret letters, which Mom found after he died, he wrote about his own impoverished youth. He wrote it, I’m sure, when Mom traveled back to Virginia to see me and my sister and the grandkids; sitting on the couch—still his office away from the office—writing on a legal pad in his lap.

“I’m listening to some old country music tonight that is triggering massive memories of my childhood,” he wrote. “Sometimes the flashbacks are so strong I wish I could record it. If you could see them, you would probably cry in sadness where I could cry in happiness. Although the times were tough, they were good because they made me what I am. Therefore,” he said, “they bring me happiness.”

It’s a staggering thing to say.

I am a product of my pain, and therefore my pain brings me joy.

He’s thankful for a childhood without heat, without money, at times without food. For hand-me-down clothes; for throbbing toothaches, my grandmother pressing hot compresses against his jaw to ease the pain of bad teeth. The constant moving. For a time they lived above a country store—the owner would fire his shotgun at rats—in a house they called the Hole in the Wall (for obvious reasons). The store became a beer joint, an unfortunate switch since my grandparents were alcoholics, though no one used that term at the time. One night a fight broke out. Granddaddy was stabbed in the arm.

“I can still remember Ma taking us out through a back window because of the riot,” Dad wrote. “I remember Daddy all bandaged up, Uncle Buddy all cut, the broken furniture, and people running everywhere when they heard sirens.” My grandfather nearly bled to death, but survived. Dad was four when it happened.

And yet despite the hardships … no bitterness. At least none that I could detect.

“Please don’t be sad when I go,” Dad wrote in that same letter. “I’ve achieved more than I ever could have imagined. I’ve been the luckiest person in the world.”

Dad made his luck, like the circuit boards he assembled at his earliest jobs. He earned everything. But he succeeded because colleagues, friends, bosses—they invested themselves in his talents. I hope that children like Garfield, the children of Bajo de Meco, find equally astute investors: vessels that will carry them to new shores, risk takers who will gamble on their growth. Because just as Julie and I have implanted some English in our tiny students, Bajo de Meco has planted some unforeseen seed in me. Long after we leave Costa Rica, the words will remain a kind of code. When some pettiness arises, some problem at work, some jerk in traffic, I’ll think, Bajo de Meco. Which means that whatever nonsense I’m dealing with is truly nonsense. That the life of the shantytown could be my own. There but for the grace of God go I. It’s a poetic way of saying that someone else’s life is way more wretched than mine. And it will leave me to wonder … Why?

Why is it them and not me? Why are these families trapped in shabby, tin-quilt homes? Why was I born to a man of ambition? A man who pulled himself far from his own hole-in-the-wall roots?

Bajo de Meco will be the place I can’t shake. Because I fear it’s an unsolvable place. It’s not like you can host a bake sale or collect quarters in cans and say we’re gonna give these people electricity and running water—Hooray! These people are squatters. Improve this place and they’ll be kicked out. And I respect CCS’s stance on charity, which is basically that it doesn’t believe in charity—that handing out money creates dependency. So nothing changes, or change comes slowly. But Bajo de Meco’s mud puddle roads and its creaky homes—homes that look like they’d tumble with a shoulder’s hard shove—they’re in me, somewhere, like the tennis balls Rafael smacked into the rain forest brush; hidden, but there, concealed, and I’m trying to ignore them—and I will ignore them for almost two years—but eventually I’ll search with the plastic bat, whacking the weeds, pushing deeper, deeper than I’d planned, still hunting, still hoping to solve the unsolvable woe.

On our last day, we attend a school assembly, which is held outside. Roberto and Enrique raise the Costa Rican flag as the kids stand in rows, fidgeting in the grass. They sing the national anthem and then the school song in a monotone chant. The porch near our classroom becomes a stage, and students present a science project on tadpoles. Awards are given. Principal Blanco holds a microphone and makes a speech. The morning is sunny and warm, so Julie and I stand in the shade of an orange tree. Since I only understand about a tenth of what the principal is saying, I mainly watch the children.

Before class started, we hosted a rousing game of bingo that filled the room with focused, excited kids. I shouted out numbers, Julie wrote them on the board.

“Twenty-seven!” I yelled. “Twenty-seven! Who has a twenty-seven!”

I felt like an overcaffeinated game show host, strutting before the blackboard in a Groucho-esque crouch. The room filled with noise, then grew quiet, a quiet I never thought possible. They waited for the next number, eyes big as I scanned the room, rubbing my chin, prolonging the drama.

“Fourteen! Does someone have fourteen!”

“Bingo!” screamed a boy to cheers and wails.

Now that we’re leaving, I think we’re finally getting the hang of this.

Julie nudges me, bringing me back to the assembly.

“I think he’s talking about us,” she says, apparently hearing our names.

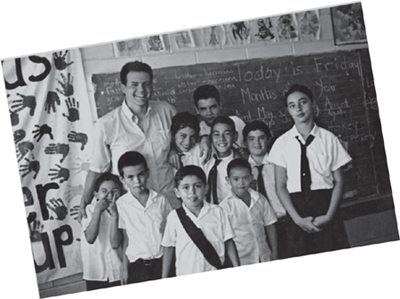

It sounds like he’s telling the students about the importance of knowing English, how English will create job opportunities later in life. He calls us up to the porch. They all applaud. A girl hands Julie a small package wrapped in pink tissue; I receive one in purple. We open them as everyone watches. It’s a key chain with photos: on one side is the school, on the other a picture of me and Julie with some of the kids, which Principal Blanco took a few days earlier. They applaud again.

The principal hands us the microphone. We say thank you in English and clumsy Spanish. Julie wipes away a tear.

She brought her camera so we take pictures, which the kids love. With each photo they jostle and push to see the digital image on the back. She snaps one of Roberto, and he frowns when he sees it: kids are making rabbit ears behind his head. So I stand behind him, hands on his shoulders, and Julie shoots again. This time he’s satisfied.

Principal Blanco later apologizes for the gift. He thinks it’s too small. I try telling him it’s one of the most touching things I’ve ever received.

Maybe, as Hannah noted, the kids learned one or two words from us. Maybe we helped improve the system: Julie and I were only the third group to work at the school, and moving forward, based in part on our evaluation, the English program will be a class, not a club, and volunteer teachers will stay for three-month stints, so there’s more continuity. Principal Blanco can use his limited funds to invest in computers for the school, rather than hire an English teacher.

When the van arrives to pick us up, kids rush into our room, even older kids, sixth graders that we hadn’t been teaching. We receive hugs, kisses, handshakes. A large group of students walks with us to the road. It is a warm, wonderful moment, yet sad, because we know we won’t see them again, that we’ll soon fade from their school-age minds. But maybe they’ll remember a few words of English. Maybe we’ve implanted a verb. To think. To hope. To run. To learn.

We say goodbye to Jonathan and James—they’ll work in Costa Rica for ten more weeks—and leave the CCS house in the afternoon with a group of departing volunteers, including Hannah. After unloading our bags at the Holiday Inn in San José, Hannah joins Julie and me for dinner. Parts of San José are lovely, such as the stately white, Old World-influenced National Theater, but as we search for a restaurant, the side streets smell of sour piss and exhaust.

We find a serviceable restaurant near a pedestrian mall. “Oh look,” says Hannah, surveying the menu. “Rice and beans.”

The discussion turns to Bajo de Meco. Our first day there, Hannah corrected a girl—maybe twelve or thirteen years old—who was pushing some kids off a swing. Hannah was later reprimanded by Maria of CCS.

“That girl was my instantaneous best friend, and then I was playing with some of the younger kids and she was really rude. I told her she was older; she should share. I mean, she should know better. Maria told me I was wrong. She said the girl had been sexually abused as a child and that’s why she was so angry. But this girl was almost violent toward these little kids. I was telling her how to act appropriately and Maria was excusing it.”

Before working for CCS, Maria had a job saving children from prostitution.

“It’s legal in Costa Rica and kids were dumped into it by their parents,” says Hannah. “So she was supersensitive to it. And you know, some of my students have tumultuous home lives, so when I find out, I give them extra slack. But Maria and I had a screaming match. Because yes, what happened to this girl was awful and unforgivable, and she should receive extra special care, but when her behavior is harming others who can’t defend themselves, it’s not a carte blanche situation. I have a girl in my class back home who was molested, and she’s angry—she cursed out one of our football players—and I didn’t write her up or call home but I did throw her out and then called the boy’s mother to say she raised him well because he kept his composure—you know, to reward him and not castigate her.

“That girl in Bajo de Meco had good reason to hate the planet but she was bullying smaller kids and acting like a nasty fuck.”

A waiter brings our drinks. I sip my soda from the bottle, not wanting to risk a tummy bug from the ice. Hannah looks serious.

“I was sexually molested as a young child, too, so I don’t speak from my butt on this.” She begins to tell us about her experience. As she does, a team of mariachi guitarists in matching black gaucho costumes stand before our table and play what sounds like the Mexican hat dance. We sit, silenced, as the three guitarists pluck their perky tune, Hannah’s personal pain and perseverance lying somewhere on the table between our empty plates.

At Bajo de Meco I’d sneak peeks of Julie as I searched for tennis balls in the brush with Rafael, poking the weeds and tall grasses with the plastic bat. I watched her play a singsong pattycake game with some of the girls and volunteers. I watched her bowl with a little boy using a tennis ball and rock-filled Pepsi bottles. I watched her play dodgeball, scooting across the cleared dirt, laughing, almost shrieking, twisting to avoid being hit.

On that inevitable day when it’s my turn, like Dad, to fall to the earth, this is the image, the sound, that will flash in my dying mind. Dodgeball. Julie giggling, the red rubber ball whizzing past; the ball as red as her cheeks. I hadn’t seen her laugh like this in a long time. I could watch her laugh forever.

A few months after we return home, I dream, for the first time in a long time, about Dad. I’m standing on the sidewalk of a four-lane street not far from our house. It’s dark. The woods and houses aren’t visible. Everything is black except for the sidewalk.

He approaches from far away. We don’t speak. He looks at me, hugs me in that heavy pat-on-the-back manner men use when they embrace. And then he walks away, down the sidewalk, then up the hill beyond. It’s the last time I dream about him.