![]()

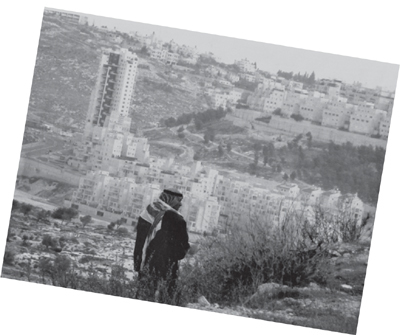

A PALESTINIAN PONDERS AN ISRAELI SETTLEMENT

NEAR BETHLEHEM.

LATE ONE AFTERNOON IN Ecuador, I was peeling off dirty clothes for a shower when something slammed against the cabana’s sloped metal roof. My first worried thought: the cabana’s been hit by a meteor. I opened the door and rushed onto the wood bridge to the path. There in the dirt, a large white bird, bigger than a football, lay on its back, its claws twitching, its neck twisted.

I hurried back to the room, slipped on my boots, not bothering to tie them, and ran up the path to the lodge. Mika was talking to some folks at the table where I’d spent two days dropping larvae into alcohol.

“Hey,” I told him, interrupting his conversation—this was the first time I’d spoken to him, I realized later—“some kind of bird just hit our roof—I think he’s hurt.”

We ran back down to the cabana, along with Zachary, the machete-wielding Robin to Mika’s Batman. Edward, the amateur ornithologist, hurried down as well.

The bird squirmed on its back.

“Looks like a quail dove,” said Edward.

Mika got down on one knee, picked up the dove, and nestled it in his red sweatshirt, holding it against his stomach.

“Best thing to do is keep him warm,” he said.

He took the dove back to his cabana, cradling it. When I saw Mika at dinner that night, he said the dove was woozy, though it eventually stood on his finger, and its pupils had stopped dilating. Mika left it outside on a stump. The next morning, he stopped me at breakfast.

“I have news on your dove, mate,” he said. “When I checked the stump this morning, there was a bit of poo and a few feathers. So I suspect he took off. Though he might have been someone’s dinner—he was right at puma height.”

Either way, a happy ending. It all depends on how you define a happy ending.

The hour-long drive from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem reminds me of winter in northern California. The mild December temperatures, the mountain highway, the yellow streetlights as evening turns to night. Until my folks moved back to Virginia, Julie and I would visit them once a year, usually after Christmas, landing in San Francisco and heading to my parents’ home near San Jose. Julie loves skiing, so we’d drive to Lake Tahoe, my parents gambling in the casino—Mom addicted to slots, Dad playing video poker—while Julie and I hit the slopes at the nearby Heavenly resort.

The first time I went skiing, back in high school, two friends tried to teach me. We went to Ski Liberty in Pennsylvania, riding to the top of the Dipsy Doodle slope, which is about as menacing as it sounds. I dismounted from the ski lift, slowing my momentum by falling face-first in the snow. My friends swooshed to a people-free area by a clump of white-covered pines, and I followed, wobbling and slipping and tumbling, like a gunshot victim on skis. With a little help from their instructions, I developed the following technique:

Ski three feet.

Fall.

Stand up.

Ski three feet.

Fall.

Start to stand up—fall—stand up—ski—

Fall.

I was so bad that I finally removed the skis and walked back down the hill, which was humiliating, though faster than if I’d “skied” to the bottom. After a lesson I improved quickly. Julie never tires of skiing—she’d love nothing more than a monthlong ski trip—but after a day or two on the slopes I’m done. My main objection is that skiing takes place in the cold. I just can’t see going out of my way—packing thick clothes, making airline reservations, taking off work, traveling—all to visit a place that’s far colder than the cold at home.

Dad enjoyed living in California, and developed what I consider a fairly sane policy about snow. Basically—

If I want to see snow, I’ll drive to the Sierras and look at it, and then I’ll drive home.

That was probably his only regret about moving back to Virginia: the cold. In February, four months before he died, he and his golf buddies played eighteen holes in 20-degree weather. When the ball hit the fairway, it was like hitting asphalt, he said; the ball would bounce fifteen feet in the air. For me, the cold feels right only at Thanksgiving and Christmas. Maybe I’ve been brainwashed by the corporate Christmas mythmakers, but Santa was headquartered in the North Pole (as opposed to, say, Pensacola) and the TV Christmas shows were all set in winter wonderlands. Had I watched Frosty the Strawman each year I might feel different.

This is the first time I’ll be away from my mom and my sister and Julie over Christmas, a separation the mild weather accentuates. In some ways, it doesn’t bother me. Because here’s a little if-you-want-children-but-don’t-have-children secret: Christmas is the shittiest time of year to not have kids. That’s when parents go to Christmas pageants or take the kids to see Santa; when the whole family decorates the tree. (Some parents, I realize, might say this is the shittiest time of year because they have kids.) And yet I feel Grinch-like for leaving Julie, because she loves Christmas as much now as she did as a kid. She wraps garland around the railings, hangs up lights, wears Christmas sweaters and socks. We own, I’m convinced, the East Coast’s largest collection of Christmas music, from the Chipmunks to the Mormon Tabernacle Choir. And this is a time of year when you’re supposed to be with loved ones.

So what we have here is a classic contradiction: I’m kind of happy to be gone, except that I’m sad to be gone.

Every human being, whether in Santa’s workshop or San Jose, the West Bank or Northern Virginia, is a red-blooded, oxygen-breathing contradiction. I was so concerned about climate change that I flew to South America in a carbon-spewing jetliner. In my attempts to help others I’ve neglected the people closest to me. While in China, I missed my nephew’s college graduation. I missed Mother’s Day. As I climbed the Andes in Ecuador, I missed the funeral of Adam’s dad. And now I’ll experience Christmas in the Holy Land—the most contradictory spot in the world—spending two weeks in the little town of Bethlehem, a town of hope and hopelessness; the birthplace of a pacifist savior whose name has justified centuries of killing; missing not just Christmas, but Julie’s birthday.

Julie was a Christmas baby. Born on December 25.

And so I arrive in Israel with a sort of guilty optimism: guilty for what I’ve left behind, hopeful for what I’ll find. I’m here because of Jonathan’s still-sturdy Costa Rica philosophy—you only learn about yourself when you’re outside your comfort zone—but also because … if you want to make a difference in the world, you need to see the world differently. You need to move beyond your assumptions and experiences. And if you want to understand suffering, you need to go to Palestine. The Palestinians have no monopoly on suffering; they’ve both endured suffering and inflicted it. We all suffer. Rich, poor, Muslim, Jew. But understanding suffering without visiting Palestine is like understanding the Bible without reading Genesis. Nowhere else on earth do the elements that so make us human—violence, hope, compassion, pain—seem on such stark and jarring display.

It begins in a back room at Ben Gurion International Airport in Tel Aviv. I’m escorted there, shortly after deplaning, by an airport security agent. As security personnel go, she’s pretty: formfitting, no-nonsense pantsuit, brown hair in a ponytail, more like a businesswoman than a cop, or whatever her inspect-the-traveler role may be.

The room is for those who are deemed threats. I suppose I should have expected extra attention given the country’s reputation for scrutinizing passengers, and given that I’m traveling to Bethlehem, although everything started normally. I left the gate and marched with the masses to the passport control booths, where a bored twentysomething woman inspected my passport.

“What will you be doing while in Israel,” she droned.

“I’ll be in Jerusalem for two days and then two weeks in Bethlehem.”

“What”—sigh—“will you be doing.”

“Oh,” I said with a nervous laugh. “I’ll be sightseeing in Jerusalem and volunteering in Bethlehem.”

My volunteer organization, Volunteers for Peace, forwarded a warning before I left, a message from our hosts in Beit Jibrin, the sixty-year-old refugee camp where I’ll be staying:

Even if the situation is calm now, you should expect that the situation may get tense. It is important to know that as a foreigner you are supposed to have freedom of movement (in comparison with the Palestinians) and security. But because your presence in Palestine is embarrassing to the Israelis who are committing crimes against the Palestinians you should be aware that you might not be welcome by them.

Not welcome? Me? How could I not be welcome? I’ve come here with what I believe is a typically American view of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Yes, it’s ping-pong politics. Back-and-forth violence. Back-and-forth outrage. Endless retaliation and blood. But when I see Israelis on American TV news, I see statesmen in suits. When I see Palestinians, I see hoodlums throwing rocks. Israel is our ally. Harry Truman considered recognition of Israel one of his chief accomplishments. The nation is a world leader in science and technology. Its citizens have persevered, and thrived, in the face of hideous terrorism. And yet … (This is the land of And yet…)

And yet … the state of Israel was founded on land where Palestinians had lived for a thousand years. Imagine being forced from your home, the home of your father and grandfather, the home of generations. Imagine a life of marginalization and harassment. Since 1967, Israelis have demolished 24,145 Palestinian homes, according to a truth-in-reporting group called If Americans Knew. The Palestinians are branded as militants, yet from September 29, 2000, through December 2009, a period that included the Second Intifada, the number of Palestinians killed was six times higher than the number of Israelis killed. As I write this, more than seven thousand Palestinians are prisoners in Israeli jails.

Always look at the other side, Dad wrote. Often you don’t fully understand things unless you put yourself in the other person’s shoes.

In 1938, Mahatma Gandhi wrote about the Holocaust, and the “Arab-Jew question.”

My sympathies are all with the Jews. I have known them intimately in South Africa. Some of them became lifelong companions. Through these friends I came to learn much of their age-long persecution. They have been the untouchables of Christianity. The parallel between their treatment by Christians and the treatment of untouchables by Hindus is very close.... But my sympathy does not blind me to the requirements of justice. The cry for the national home for the Jews does not make much appeal to me.... Palestine belongs to the Arabs in the same sense that England belongs to the English or France to the French. It is wrong and inhuman to impose the Jews on the Arabs. What is going on in Palestine today cannot be justified by any moral code of conduct.... I am not defending the Arab excesses. I wish they had chosen the way of nonviolence in resisting what they rightly regard as an unacceptable encroachment upon their country.

The more I’ve learned about the conflict, the more conflicted I’ve become.

I share none of this with the woman in the passport booth, who doesn’t appear curious to learn Gandhi’s worldviews, let alone my own. She hands me a slip of paper to give a gate guard, the next round of security bureaucrat waiting ahead.

Secureaucrats, I dub them. This uniformed secureaucrat gives my passport to the pantsuit secureaucrat, who immediately asks questions—

How long will you be here? What will you be doing? Where will you be volunteering?

I don’t know where we’ll be volunteering. It’s a series of projects, rather than working at, say, a school. We’ll receive the schedule when we arrive in Bethlehem.

“I know at least one day we’ll be at a farm.”

“A farm?” she says skeptically.

“A farm.”

The V-word—“volunteering”—is probably the reason for my special attention, because it means I’ll be interacting with locals, though “volunteering,” to me, seems like a pretty positive word. I try to imagine what other upbeat words might raise concerns—

I’ll be making balloon animals for two weeks in Bethlehem.

Balloon animals?

Balloon animals.

I see no balloons in your bags....

I once read a book about post-9/11 U.S. security efforts, called Fortress America, which discusses the Israeli approach to security. One tactic is for screeners to ask constant questions, some of them innocuous, in the hope that you’ll eventually screw up. It’s like someone throwing a bucket of baseballs: the more balls that come, the less likely you are to catch them. I have nothing to hide—the most dangerous thing in my bag is an electric razor—but I don’t want to get stuck here, so I decide to be perky, big-time perky, figuring if I’m cheerful they’ll assume I’m a dork as opposed to a terrorist. And so I tell her we’ll be working at an olive farm, and I say it in an Up With People golly-gee-willickers kind of voice.

Guess what, boy and girls—we’re going to an olive farm! Hooray!

“What do you do for a living.”

“I’m an editor.”

“You’re a journalist?”

“I’m an editor.”

An editor! Yippee!

She says she needs to scan my luggage. It’ll only take a few minutes. I pick up my backpack from the carousel.

“Do you get paid to come here?” she asks as we walk.

“No—I wish.”

“Your ticket is paid for?”

“I actually pay to volunteer.”

She looks at me funny.

“It’s screwy, I know.”

This is when I notice we’re walking—alone—past dormant carousels in an empty corner of the airport. We stop at a closed door. She slides her ID card through a slot to enter. I smile, wondering if I’m about to be interrogated. Inside, another woman runs my backpack and carry-on bag through a scanner. She walks to a machine and pulls out a long blue plastic spoonlike wand with a square cloth on the end that could easily—or not so easily—be shoved up an orifice. Next she opens my bags, rubbing the insides with the wand, checking, I assume, for explosives, inspecting everything—my sleeping bag, shirts, camera, phone, the backpack itself. The top of my electric razor pops off and whiskers spray on my socks.

“What is this,” she asks, holding up a small purple vinyl bag, the top tied in a knot.

“Toiletries. You know—brush, shampoo, toothpaste.”

She unties it, empties it in a bin, and takes it to another room.

An irritated middle-aged Brit is undergoing the same procedure. His sunglasses are propped on his head; he looks like a jet-setter not used to being detained. A morose dark-skinned couple—they might be from Mumbai, based on a label on one of their packages—sit in plastic chairs. They look like they’ve been here for hours.

The guard returns the bin from the room behind us, and tells me to go to the room.

“Empty your pockets,” she says.

I walk through a metal detector. Three times. Finally the pantsuit secureaucrat hands me my passport and says I can leave. My clothes sit in a mound in my open backpack, and on top are the blue underpants I accidentally received from the hotel laundry in China. That’s right, I’m still wearing them. Seeing them makes me smirk, and that smirk bloats into a giggle, which I suppress, because giggling at the end of a security shakedown would surely reignite the process, and explaining mystery Chinese underpants to humorless secureaucrats would be a chore—

I’m sorry—these underpants belong to another man—I didn’t steal them, though—is it stealing if you wear another man’s underpants without his knowledge?…

I mush everything in my bag, not bothering to fold my clothes. The pantsuit guard thanks me. I nod and leave, and the Mumbai couple continue sitting with long faces, having no such trouble suppressing smiles.

I’m staying at the Christ Church Guesthouse in Jerusalem, less than a five-minute walk from Jaffa Gate and the ancient city wall. I collapsed on the bed in my clothes the night before; now I enjoy a guesthouse breakfast of pitas, olives, tomatoes, and cheese, and dedicate myself to the things one must do while in Jerusalem. Before heading to the Western Wall, I dive into the Old City, descending down tunnel-like David Street, a claustrophobic hub of stone steps and tourist-shop stuff, the tin-awning stalls lined with postcards, plates, menorahs; scarves and patterned dresses high on hooks; “Guns N’ Moses” and “Super Jew” T-shirts.

I pass the Petra Hostel, where Mark Twain once stayed—it’d be easy to miss, a small red sign above the door, the harsh lighting making it seem more like a subway stop—and then a jewelry store and more stalls and more stuff, stuff, stuff. In one shop a man kneels with a black umbrella, until I realize, no, it’s an automatic weapon. I’ll pass multiple men with weapons. One of the volunteers I’ll meet tomorrow, a woman from Spain, says she told an old man in Jerusalem how startling it was to see so many guns, and his surprised response was:

Really?

A shopkeeper sees me and waves his arms. “I have special deal for you.” An African woman, part of a small tourist group, haggles with the shopkeeper next door over luggage.

Sixty!

No more than forty-five!

Fifty!

I wander down side streets, the smells shifting as I walk. Baking bread … ammonia … something citrus (tangerines?) … an unknown spice. Soldiers in green uniforms pass with rifles dangling; a monk strolls by in a hooded robe. Hasidic Jews walk and chat in their customary black suits, white shirts, and long beards.

When I retrace my steps and return to Jaffa Gate, past fruit stands and high tile street signs in Hebrew and English and Arabic, the street feels spacious, the new city extending beyond the open gate. I walk in the sun along the Old City wall through the Armenian quarter, descending a hill to the Western Wall entrance, the golden Dome of the Rock behind it, passing through a security shack with an X-ray machine and metal detector. A sign reminds visitors that the divine presence is here. The shack leads to a plaza, often described as an open-air synagogue, the wall behind it a backdrop to constant photos. A group of children hold balloons above their heads. About fifteen soldiers, college-age, men and women, pose in rows; the women good-looking, earlobes with pierced pearls, brunette ponytails, sunglasses on the tops of their heads; the men with cropped hair, grinning for the photo.

A fence blocks entry to the wall. You can enter if you wear a yarmulke, but I stay back, preferring not to gawk as people pray. So I gawk instead from a distance, admiring the Hasidic Jews as they rock, the cracks of the wall filled with prayer notes. Two boys throw rolled-up balls of paper at each other; kids will be kids, even at one of the world’s holiest sites. Near the fence young men in white shirts and white yarmulkes dance in a circle around a table covered by a wine-colored cloth, the table loaded with books and scrolls. It’s joyous to watch. Even here in the plaza, away from the wall, people pray.

Through an enclosed ramp near the women’s side of the wall I reach the Temple Mount—Muslims call it Haram al-Sharif—again going through security. This is the entrance for non-Muslims. The Temple Mount is quiet, like a park, open and green after the claustrophobia of the Old City’s streets. Boys play soccer on the grass near the back. I wander, then reenter the Old City maze, strolling in shadows past merchants and men smoking a hookah pipe. Feeling lost, I go back the way I came, but a cop with a rifle stops me: this is a Muslim entrance. And so I roam, holding my open map like an idiot tourist, before discreetly latching on to an Asian group that asks shopkeepers for directions. When I make it back to the shops of David Street, the sunglasses racks and T-shirts feel like home.

And then comes an oh shit moment.

Late in the afternoon, I pay sixteen shekels and embark on the Ramparts Walk: a walk along the top of the ancient city wall. Starting from Jaffa Gate, I stroll for about twenty-five minutes, admiring the views of the Dome and the Old City, the water tanks and satellite dishes on clustered roofs. With the sun setting I turn around, eventually exiting through a tall black turnstile at Damascus Gate. I walk down stone steps, push the gate—

And it doesn’t move.

I shake the gate—clang clang clang clang.

Nothing. A small silver, U-shaped bike lock is on the handle. I march back up the steps to the turnstile. The bars turn an inch or two, then lock.

As darkness descends on Jerusalem, I am trapped in a prison of seven steps.

I could be caged here the entire night. That’s my first thought. And it’s already getting cold. My hands are in my pockets; the chill creeps through my sweater. But someone will pass, right? I’m close to Damascus Gate, which is heavily traveled, although as I look through the bars of my unexpected prison, rock-and-cement walls at my sides, all I see is a rising, curving stone street that’s rapidly becoming dark.

In front of me is a two-story apartment building. A small girl walks onto the balcony above to collect flapping laundry. I shout up to her—

“Hey—excuse me—do you know anything about this lock? Is a policeman nearby?”

She rushes back inside with a pile of sheets.

I’ll wait five minutes or so, I decide. See if a cop or soldier walks by, then attempt to climb out. I could use the gate latch as a step—maybe—lift myself up, put my other foot on top of the gate, and climb over. Maybe. The other option is to walk back up the steps and shimmy across the ledge to the gate, though there’s precious little room for shimmying. And even if I could stand on the top of the gate without falling, I’d need to leap ten to fifteen feet to the stone steps below, which seems like the ideal strategy for breaking an ankle. I’m about to attempt it, despite the foolishness of it, when a young black-haired boy, maybe eight years old, runs up to the gate.

“Hey!” he says.

He slips his skinny body through the gate bars, first his head, then his chest, green sweater and black jeans, then his white sneakers. It’s the kind of thing you can do when you’re eight.

His head is about as high as my hip.

“Come,” he says.

He runs up the steps.

“Come.”

The tall turnstile is a like a revolving door, only instead of glass its four sides are black horizontal bars. He twists it to the right, just enough to slip around the bars before they lock, then pushes it to the left, slipping by the next set.

Why didn’t I think of that?

I do the same. It’s not as easy for me, obviously, but I manage to squeeze by. He waves. He wants me to follow him on the wall.

“Come.”

He walks, I follow. The Muslim call to prayer sings from loudspeakers. He stops, points at the view of rooftops and says something in Arabic; what I imagine is a tour guide spiel. We pass a school below. On an asphalt basketball court kids in gym clothes dribble from one baseline to the other. Two coaches seem to be critiquing their dribbling.

“Basketball,” says my eight-year-old rescuer.

“Yes—basketball,” I say.

He waves playfully to the people below, and despite the energetic bounce to his tyke-sized steps, the more we walk along the wall, and the darker it gets, the more I wonder if he’s leading me to a surprise meeting with his five or six much bigger brothers for a game of separate-the-American-from-his-shekels.

“Here,” he says.

I’m guessing we’re at Herod’s Gate. We descend the steps to market stalls selling fruits and breads under fluorescent lights, the women wearing head scarves, carrying plastic bags.

“Money,” he says.

Okay, I’d figured I’d give him something before he even asked, and I’m happy to be free without getting robbed or breaking my tarsal bones. I hand him a few shekels, pat him on the back, say thanks. He scurries off. I walk to a street outside the wall and head back toward Jaffa Gate, following a singing, torch-carrying Hanukkah throng to the Tower of David, directly across from my hotel. As I walk, it occurs to me—

I wonder if the kid is the one who locked the gate.

When Julie decorates our home for Christmas she places a red wooden toy soldier on the narrow mantle above the fireplace. The soldier has a happy Playskool expression, black grenadier hat, swinging arms. Dad brought it home from Denmark. He worked there for a few weeks after I was born, sent by his employer to repair check-processing machinery for banks. I’m embarrassed to say we never discussed what he did there, or what he experienced. Sometimes I wonder: why didn’t we talk about this? You think you know the people you love until they’re gone, and then you realize the questions you never asked, the questions that seem less important when they’re here.

I was six months old when Dad went to Denmark. He returned to find me even fatter than when he left. I was so wide when I was born, and so long, that I ruined my mother’s insides for future siblings. While Dad was gone, Mom took me to Sears for a baby picture. I wore a little red-jacket suit, but the bow tie wouldn’t fit around my too-fat neck.

Denmark was Dad’s only trip to Europe. He never lamented this. I think he was grateful, even a little amazed, that he made it to Europe at all; amazed that a poor farm kid could travel to China, to journey so often to Japan. I’ve had more advantages in life, but I feel grateful as well when I travel. I feel grateful my last morning in Jerusalem as I walk the Via Dolorosa, the route Jesus supposedly followed while carrying the cross; as I enter the dark, loud Church of the Holy Sepulchre, which Christians believe holds Jesus’s tomb; as I continue to misplace myself in the Old City’s cramped, confounding streets. It’s humbling to wander these tight ancient alleys, to know this is the center of faith for so many people, a center of human history.

I eat a simple tomato soup lunch back at the guesthouse, pay my bill, heave my backpack over my shoulders, then head out past tourists, locals, soldiers, and scooters, exiting through Jaffa Gate. The meeting point for volunteers is the Faisal Hostel, just outside the Old City wall, about a twenty-minute walk. When I arrive I’m sent upstairs to a narrow lounge, one wall lined by an orange couch. People mill about, chatting. It’s like a UN summit. I hear conversations in French and Italian, the accents of Irish and Brits and Scots. I talk with a Croatian woman and a woman from Spain. A Finnish girl looks like Dora the Explorer. It’s a mix of ages—an Italian couple appears to be in their sixties—though more weighted toward the college crowd. The common denominator is that all of the Europeans seem to smoke: the room is foggy, like the Ecuadoran cloud forest on late afternoons.

We board buses crowded with late-afternoon commuters, led by Perrine, a lovely Frenchwoman who lives in the West Bank. She’s here because our Palestinian hosts, given that they’re Palestinian, can’t enter Jerusalem. Palestinians can only enter if they have permits, like the Palestinian laborers, almost entirely men, who pack the bus.

We arrive at the Gilo checkpoint to enter Bethlehem. The men scramble from the bus: they must pass through the checkpoint—they must be out of Israel—by a certain time or they lose their permits.

The checkpoint is like a prison. We head through a penned passageway, pass through turnstiles, then walk to booths. A soldier with a machine gun waves me forward. I show him my passport, then walk through an outdoor area to another turnstile. Palestinian laborers pass through here twice a day, every day; through this cold, colorless chamber of echoes and insinuations, of metal bars and black weapons, of stern and staid expressions.

As we exit, we see the separation wall. It’s overwhelming: twenty-five feet high—roughly twice the height of the Berlin Wall—topped here by metal posts and a chain-link fence, built in vertical planks, one next to the other, concrete and gray.

The Israelis call it a security barrier. And from the Israeli perspective, the $2 billion wall is a success, reducing the influx of suicide bombers and protecting settlements. Another unofficial benefit: although the government states on its official security fence website that the wall “does not annex any lands to Israel,” other organizations say the barrier has claimed roughly 9 percent of the West Bank’s land—in addition to land already snagged for settlements. For Palestinians, the “Apartheid Wall” has led to the loss of farmland, divided families and towns, made it difficult to reach jobs, doctors, schools—to do the simplest of activities. The wall may make sense militarily for the Israelis, but there’s an unhealthy paradox here, like a cigarette that both treats and causes cancer. The short-term cure inflicts a long-term curse.

We walk down an empty street, led by a few locals here to greet us, the wall looming to our right, splattered with graffiti, a mix of slogans (“Build bridges, not walls”), occasional humor (“Can I have my ball back?”), and elaborate paintings. One looks like an acid trip—a scene from Yellow Submarine: splashy colors, a wavy rainbow, a giant smiling ladybug and butterfly.

In a red heart with white lettering someone has written, “This wall is a big bullshit.”

The slogans continue:

Palestina Libre

Only Love Will End War

Tear Down This Wall

And then a peace sign of black, green, and red—colors from the Palestinian flag; a charging rhino that seemingly crashes through the wall; a silhouetted man and woman, holding hands, a fighter jet descending upon them.

I can never decide if the paintings beautify the wall or stain it. It doesn’t really matter, because the gray still dominates, a concrete plague along the land.

I stroll with Aarif, an independent photographer who’s carrying a shoulder bag and a camera with a massive lens. He’s young—twenty-six—though I would have sworn he’s my age. He’s one of our escorts, a freelancer who works for a news agency.

“I notice almost all the graffiti on the wall is in English,” I say.

“It’s mostly done by internationals.”

Aarif gives a brief anti-wall summary, which I will hear frequently: five years ago, the International Court of Justice issued an opinion stating that the wall is illegal. The wall has been denounced by organizations ranging from Human Rights Watch to the Red Cross.

“You American?” he asks.

“Yeah—what gave it away?”

“I can tell by the accent.”

“That’s probably not good…”

“No—that’s good.”

“I just mean an American accent isn’t as nice as a British accent.”

“No, really—you sound Hollywood. Like Rambo.”

“You’re not the first person to tell me that.”

We talk about the conflict as we walk down stark streets. Like a lot of young Palestinians, he speaks excellent English.

“The problem is you have extremists on both sides, so there’s always a cycle of retaliation. People grow up in an environment where family members die.”

I stare at the wall. It’s grotesque. One of the most grotesque things I’ve ever seen. “We need a thirty-year truce,” says Aarif, “just to clear people’s minds.”

We reach the refugee camp, dropping our bags inside the Beit Jibrin Cultural Center, our base of operations for the next two weeks. The center is a colorful anomaly on a trash-strewn street—more like an alley, really—the doors a welcoming blue. A mural extends across the building at street level: a man and woman holding hands, children at their sides; the neutral expressions of mannequins modeling clothes. The children wear T-shirts with an image of Handala, a popular comic character. He’s a youth drawn in outline form, seen from behind, hands at his back, his round head with nine protruding rays of hair, like a refugee Charlie Brown. “He is a 10-year-old boy who lives in a refugee camp and observes the injustice of the world around him,” I read in the cultural center, better known as the Handala Center. “He acts as a symbol of the refugee cause and is a testament to its creativity, steadfastness and resilience.” Handala’s creator, Palestinian cartoonist Naji al-Ali, was assassinated by unknown assailants in London in 1987.

Black graffiti runs across the mural; black power lines crisscross the narrow street. Everything is hard here. Asphalt and concrete and iron. No grass. No playgrounds. The few trees are almost invisible, consumed by squat structures. The most prominent tree isn’t even real; it’s painted on the side of a tiny market near the Handala Center, the tree’s trunk and bare branches a pencil-lead gray, wrapped in barbed wire, a ringed sun like a dim dartboard behind it.

Of the fifty-nine Palestinian refugee camps in the Middle East, Beit Jibrin is the smallest: roughly two thousand people in a 0.02-square-kilometer neighborhood of three- and four-story apartment buildings, the windows covered by bars. Most families fled here from the Beit Jibrin village about thirteen miles northwest of Hebron, and more than half are descendants of the Azzeh family (which is why the camp is frequently called al-Azzeh). The village was included as part of an Arab state in the UN’s 1947 Partition Plan, but was captured by Israeli forces in the 1948 war. Forced from their homes, the refugees and their children, and their children’s children, have lived here ever since, along with refugees from the 1967 war.

“These camps have been here for sixty years,” says Mahad, one of our hosts, his accent thick as the black beard stubble on his long thin face. “We are guests, but we will return to our villages. It may be sixty more years, it may be one hundred years, but someday we will return.”

Mahad works at the Handala Center. Among his jobs: he records the oral history of first-generation refugees, with second and third generations conducting the interviews. He sits with us on plastic chairs in a harshly lit third-floor room, the walls void of posters or pictures, as we eat soft pitas filled with hummus and falafel. Later we each pay a two-hundred-dollar fee to the International Palestinian Youth League, which is running the volunteer program, then shuffle up echoing stairs to the large fourth-floor room where we’ll soon have nightly meetings. We sit in classroom-style chair-desks as Adli Daana, IPYL’s charismatic secretary general, gives a welcome speech. A handsome man, probably in his late forties, he exudes a politician’s aura, the ability to work a room, striding with an actor’s self-assurance in a leather coat that looks like a racing jacket, a red stripe with white border across the arms and chest.

Daana accuses the Israeli government of apartheid. “We want volunteers to see this, to see the difficult situations that Palestinians face every day. But we also want you to see the real Palestinian people. We love life,” he declares. “We love it.”

IPYL was founded, he says, to combat hopelessness, the lack of direction in the lives of Palestinian youth. Eighty percent of young Palestinians are depressed, according to a United Nations Development Program survey. The numbers are worse in Gaza, where 55 percent of youths described themselves as “extremely depressed.”

“Jesus Christ was a Palestinian,” Daana tells us, this being Christmas. “He was born here, he lived here, he was raised here.” Jesus was also a Jew living in what was then known as Judea, lest we forget. Bethlehem still has a large Christian community—by law the mayor must be Christian—though their numbers have fallen from 92 percent of the population in 1948 to under 50 percent of the town’s 27,000 inhabitants today.

Once Daana is done, Fateen, who’s running our two-week program, passes out a schedule and discusses our work—from building rock walls to cleaning streets—and social activities. He’ll try to get tickets for the Christmas Eve service at the Church of the Nativity, but given the region’s relative calm, various dignitaries and politicians will be attending, so tickets are scarce. We will, however, decorate a Christmas tree, though instead of traditional ornaments we’ll use bomb casings and tear gas canisters and other leftovers from Israeli attacks.

Perhaps alarmed at how Westerners accustomed to boughs of holly might respond to barbed-wire tinsel, Daana rises from his seat and raises his hands in not-to-worry, damage-control reassurance. “It’s symbolic,” he says, chuckling. “Don’t worry. It’s symbolic.”

In another symbolic gesture, we male volunteers will be not be sleeping in the same building as the female volunteers, unmarried slumber being a no-no in a Muslim community. The women will sleep here in the center, packed together in a ground-floor room, while we men will stay in a second-floor flat across the street. We gather our things and trudge in a masculine pack down a narrow alleyway in the dark carrying backpacks and blankets. The blankets are padding for the floor, which is where we’ll sleep. It’s a two-room unfurnished apartment with all the charm of the checkpoint: peeling white paint, the floor a spackled linoleum gray. Outside it’s cold, probably in the low 40s, though it feels colder in the apartment. As far as I can tell, no building in Beit Jibrin has central heating. Our chilly flat has a sole electric space heater, which sits near the bathroom door.

The bathroom has a toilet and a sink. That means we have roughly twenty men and one toilet. Oh—and no shower, though there’s one in the unit next door, which is where Fateen and a few volunteers will sleep, since the flat has quickly filled with bodies and packs. A path extends between sleeping bags to the toilet and a smaller back room, where seven of us will sleep. It’s like a room for interrogations: a single harsh lightbulb dangles on a wire from the ceiling. I snag two of the blankets, spreading them under my sleeping bag. There’s no carpet, so the floor is hard and cold. I crawl into my sleeping bag and zip the bag up around my head so only my face is exposed. The eye mask I brought to block sunlight warms my nose.

I’m sandwiched between Burt, a boomer-age bearded Belgian, and Mike, a college-age Brit. Two Italian men snore. Doug, a terrifically nice guy from Philly who’s here with his wife, is stuck between the stereo snoring. “It was like sleeping on an airport runway,” he says the next morning.

I wake up several times during the night, stiff from the linoleum. I dream about Adam and his son Erik: they wear football jerseys that stretch to their feet, like nightgowns, and they can’t stop laughing. I wake up after that, and the whole idea of being home, and being comfortable, already seems strange.

Visitors to Jerusalem are sometimes inflicted with a condition known as Jerusalem syndrome. Basically, they’re so overwhelmed by the city they believe they’re prophets—like visiting Disney World and convincing yourself you’re Snow White.

I felt the opposite. I felt small in Jerusalem. I’ve felt small on this entire journey. Small compared to the Andes Mountains and China’s masses; small in my skill level and contributions. I feel even smaller in Beit Jibrin.

A friend of mine at work sometimes wanders into my office on Monday mornings, and if it’s too early, and we’re too out of it, we’ll chat for a moment in a bleary, not-caffeinated-enough way, until she’ll finally say, “I have no personality” and wander back to her office. That’s how I feel here. Void of personality. Like my humanity was quashed the moment I walked through the checkpoint, which I’m sure is the intent. Less of a man coming out than going in. Sausage grinder to the soul. And the wall. The life-sucking wall. How do people face this planked, cold, concrete snake every goddamn day?

And yet, I’m sure I’d feel different if I were Israeli.

Always look at the other side, Dad had written.

Of course, it’s hard to see the other side when there’s a twenty-five-foot concrete wall in the way.

After breakfast we walk en masse to Bethlehem. Tomorrow we’ll start our work; today is explore-the-city day. We take a side road past a mosque and an auto repair shop to reach Manger Street, about a twenty-minute walk to Manger Square, passing mom-and-pop restaurants, convenience stores, tourist shops selling olive wood carvings of the manger scene. Mountains rise in the distance, though more prominent are the settlements on a nearby hill, surrounded by security walls, backed by a construction crane. Mahad watches as bulldozers rumble up a twisting dirt road. His eyes are narrow beneath a black stocking cap, a black-and-white Yasser Arafat–style scarf—a keffiyeh—around his neck. He tells us the settlements are like military bases: the Israeli military used them to launch attacks during the Second Intifada.

At Manger Square, next to the Church of the Nativity, a massive Christmas tree stands nearly three stories high, decorated with red bells and clumps of gold grapes and red-and-gold balls. The church resembles an old stone fortress, with thin windows for firing arrows. We crouch through the Door of Humility, a short door designed to keep soldiers from charging into the church on horseback. Inside, the church is sparse but broad, the smell of incense hovering. Light from a high window streams between stone columns. Gold lamps hang from the ceiling, their shiny red tops like a police car’s siren.

Beneath the church is a crypt: here, the faithful believe, is where Jesus was born. Portions of the church date back to the fourth century. It has survived threats from the Crusades to the Second Intifada, when, in 2002, Palestinian resistors, some armed, barricaded themselves inside for thirty-nine days.

The Second Intifada devastated the local economy. With political instability came severe restrictions on travel and trade. West Bank camp residents depend on work in Israel—most of the camp’s residents worked as day laborers before the Intifada, says Mahad—but now they’re severely hampered by checkpoints and the wall. The youth unemployment rate is around 30 to 35 percent, though people here think that figure is low. In Gaza it hovers around 50 percent.

We leave the church through Manger Square and head into an old-town section, ascending tight pedestrian walkways, past jewelry stores and tourist shops and food stands. When we reach the Aida Refugee Camp, Mahad gives a ten-word history of how the refugees lost their homes.

“The soldiers, they come, they say, ‘Get the hell out.’”

Established in 1950, the camp is more than twice the size of Beit Jibrin. Aida’s original residents came from seventeen different villages, and the camp is struggling even more than Beit Jibrin with overcrowding, with 43 percent unemployment, with poor water and sewage networks. During the Second Intifada, twenty-nine housing units were destroyed and a school suffered severe damage from an Israeli military operation.

The separation wall looms over a graveyard just beyond the camp. Everywhere, the wall is tattooed with images. A single eyeball sheds a tear. Multiple black Handalas stand with their hands clasped behind their backs. Why? someone has spray-painted in black.

When the oppressed becomes the oppressor, reads another tag.

More elaborate is a yellow tractor smashing a human heart with a wrecking ball. Nearby is a quote from Gandhi—

VICTORY ATTAINED BY VIOLENCE IS TANTAMOUNT TO A

DEFEAT, FOR IT IS MOMENTARY.

We leave the road and scale a hill made of crumbled cinder blocks and occasional chunks of asphalt. The wind flaps a blue plastic tarp, half buried by rocks. Twisted cables shoot up from the debris; a rotting mattress rises from the rubble like a crooked tombstone, its mesh cover ripped. Doug finds a little girl’s white shoe. Above the toe are Valentine-style hearts.

“Were these buildings?” I ask Fateen.

“These were Palestinian houses,” he says. “They were destroyed for the wall.”

Fateen points at the wall. Towns and villages were cut in half, he says.

“There’s a couple near here—they were supposed to be married. After the wall was built, they can’t see each other because they live on different sides. They go up on top of their buildings and signal each other with hand gestures.”

We walk down a side street. The call to prayer blares above; a boy rides by on his bike and yells “Beep!” Children kick a soccer ball. A plastic grocery bag floats over the wall.

Afternoon traffic picks up as we head back toward Beit Jibrin. We take a different route, approaching the back side of the neighborhood’s gray buildings, walking past a small one-story house. A dog stands on the flat roof of the carport. How he got there isn’t clear; a rickety ladder is the only way up. Two boys and their father pull a chain around his neck, trying to get him down, but the dog is scared; yelping, crying, barking, growling; refusing to move. The father says something in Arabic, and the boys climb down and retrieve a red plaid bag, about the size of Santa’s sack. They struggle to put the dog in the bag. The dog’s howl is piercing, shrill. Eventually, after some fumbling, they succeed, lugging the pooch down as he flails in the bag. When they release him and attach his chain to a pole, the dog is still crying. The father laughs.

As we walk down the alleyway, past bullet marks on the walls, I can still hear the dog’s shrieking, horrible howl.

That evening, we see photos of suffering Palestinians: the widows, the homeless, the poor. The photos are on poster boards, set on chairs in the pale third-floor room of the center where we eat our meals. I look at the photos, then go outside, standing in the cold, in the night, leaning against a graffiti-scrawled alley wall.

I miss Julie. I feel like … I’ve never missed her as much as I miss her tonight. It’s Christmastime, her birthday is coming up—

What the hell was I thinking?

My last evening in Jerusalem, before going to bed, I sat at the desk in my humble room and wrote a note in her birthday card. I sealed the envelope, walked to the bathroom, squirted toothpaste on my toothbrush, and started brushing. And then—why then, in a bathroom, as opposed to any of the holy sites I’d visited during the day—it hit me.

I don’t want to do this anymore. I don’t want to be apart from her. Everywhere I’ve gone—Xi’an, Quito, Jerusalem—I’ve thought … “I’ll have to come back here with Julie.” Like I haven’t really been there if she’s not with me.

I feel alone, sitting on the steps, depressed by the wall and the rubble and Aida and Beit Jibrin, still hearing the terrified snivels of the roof-bound dog, feeling my blank personality like a weight behind my eyes. I send her an e-mail on my phone, any qualms about contacting home left behind in Ecuador.

I’m sorry for not being there. When Dad died, one of the big things I wondered was how we’re meant to spend our limited time. I want that limited time to be spent with you.

I have an opportunity to do things in life that others can’t. I should be satisfied with that. I am satisfied with that. Funny, though, how life works. Once you’ve figured everything out, you’re tested.

I noticed Monique the first night. She’s French, wavy black hair. I watched her smoke a cigarette with an amused smile as Marcen, a friend she traveled here with, performed a semi-mime routine, waving his arms and grinning like a clown.

I was surprised to hear the French accent one evening after a meeting as I wrote in the notepad that doubles as my journal.

“I want to know what you are writing,” she said.

I looked up from my scribbles.

“Me? Oh. You know—just taking notes.”

“But why in this horrible meeting.”

We’d met to discuss a possible Christmas party, the kind of meeting that makes you want to cancel Christmas forever.

“It was so horrible that in some ways it was funny,” I tell her.

“I don’t see anything funny. Just horrible.”

She’s right. It was horrible. Instead of just telling us, “You have three Christmas party options—here they are,” Fateen asked for ideas. Given that we have forty volunteers of varying ages and nine different nationalities, that question invited a range of competing ideas and even some anger. A volunteer named Paul, who looks like an English Ted Kaczynski and just arrived at the camp, said that instead of a party we should distribute food and soup to the homeless.

“It’s hypocritical to go the Church of the Nativity and not serve others. It’s bullshit!” he yelled. “It’s crap!”

Everyone, regardless of nationality, wore the same puzzled look that said—

Who is THIS asshole?

“Our presence here is statement enough,” said Mary, an annoyed young Irishwoman.

Paul then evoked Jesus, as well as Muhammad, in a speech that, I confess, I found incomprehensible because of his accent, though he infuriated the Irish girl even more.

“Why are you dragging religion into this? I’m not here to be religious—I’m here to be a good person!”

Fateen settled folks down: “Guys, guys…”

More Christmas suggestions spewed forth.

We should pass out candy or chocolate.

No, no—tools. That’ll make a bigger difference in the future.

The center is hosting us; we should buy something for the center.

“Speak slow,” said one of the Italians.

We should work for the elderly.

This is about building relationships—maybe we should play soccer.

We should clean houses or repair them.

“Speak slow,” said one of the French.

We should have a party for the children.

It’s a refugee camp—you can’t have a party for the children.

Why can’t we have a party for the children?

Because it’s a refugee camp.

A middle-aged Scottish woman and a bossy middle-aged New York woman, who clearly don’t like one another, began to argue. Nothing got resolved.

“Horrible,” says Monique again.

“Okay, horrible.”

“So you will show me what you write?”

“Nah—it’s not that interesting.”

She smiles, a smile that seems to say there’s more to you than you’re letting on, and heads down the steps with some of the French contingency for an outside smoke.

I stay in the room and talk with Doug and his wife, Kayla, the couple from Philly. They’re in their late twenties, and traveled to Paris, and then Jordan, before arriving here. Doug broke a bone in his lower right leg playing Ultimate Frisbee days before they left home; he’s wearing a black medical boot. Kayla plays as well. They’re fit, and thin, so I was surprised to learn that Doug played the tuba in the Drexel University pep band. He doesn’t fit the tuba stereotype.

“You should have brought your tuba here,” I say. “Some gentle tuba music might have helped soothe the anger in that meeting.”

Kayla decides I’m an undercover CIA agent, since I’m here alone and frequently writing in my pad.

“I bet you’re taking notes on all of us,” she says.

“It’s true—you should see some of the shit I’ve been writing about you.”

“I knew it! You were airdropped into the country.”

“Yes—totally top secret. To avoid detection I didn’t use a parachute.”

“And your bag is packed with weapons.”

I show her my hands. “These are the only weapons I need.”

“You’re a dangerous man, Kenny.”

We had discussed bowling one night—for the life of me I don’t know why, other than there’s not a lot to do in a Palestinian refugee camp—and I had made the mistake of saying I was in a bowling league as a kid, and had my own monogrammed blue ball that said “Kenny” in script.

Kayla finds this very amusing.

There’s one other American I chat with from time to time during my two weeks. Benjamin is twenty-eight, looks younger (though acts older), of Mexican descent, now living in New York and going to art school while working at Starbucks. He seems shy, but he’s simply soft-spoken, thoughtful. The night I e-mailed Julie, when I was in such a deep funk, I went outside, down to the dark street, hoping the chill would clear my head, waiting for dinner: there was a gas leak, so dinner was cooked on Coleman-style stoves. The Italians made pasta. We didn’t eat until after 10 p.m. Benjamin stood near the door, mainly to escape the cigarette smoke. We talked about our time here so far. We were both shocked by the size of the wall, both aware that we’re hearing one side of the story. I ask him what he thought of the Church of the Nativity.

“I don’t like to take pictures in places like the church,” he says. “Too often people miss why they’re there. I’ve seen people at art museums take pictures of paintings without actually looking at them.”

“Are you a churchgoing guy?”

“Well, I believe in God, but I don’t go to church every Sunday.”

“I guess I believe in God. I mean, I could see that God or something so unfathomable that we think it’s God created the universe or the Big Bang. But I don’t believe in a God who knows whether I brushed my teeth at night. And I have a problem with biblical literalism. You know—insisting that the world was created in seven days.”

“You ever read Kierkegaard?”

“No,” I say, admitting my ignorance of the father of existentialism.

“Kierkegaard says absurdity is essential for religion because to have faith you need to suspend reason.”

“I’m interested in philosophy,” I say, “I’m just never sure where to start.”

“It all starts with Plato,” says Benjamin. “Everything since is just an argument with Plato or just restating what Plato said. The issues never change. Modern times, same issues.”

On our first day of work I wake up early and head to the Handala Center for breakfast. As I leave the flat, I carefully open the door, making sure I don’t whack an Italian guy’s face as he sleeps on the floor. Others rise from sleeping bags, stretching, scratching, putting on clothes.

I walk down the split-level steps past graffiti-sprayed walls. Up high is a black-and-white painting of a bearded martyr, a keffiyeh around his neck; a snarling, sharp-fanged lion behind him. Painted below are two Palestinian flags, rows of barbed wire on each side. Four camp residents were killed during the Second Intifada, says Mahad. Many more were injured and arrested. Fateen says every family has a father or son who’s been shot, arrested, or martyred. People here seem resigned to it.

After eating what will be our standard morning chow—pitas, jam, tomatoes, cheese, bologna, tea—we ride in buses to nearby Nahalin to build rock walls at a mountain olive farm. Nahalin is not only separated from Bethlehem by a barrier, but it’s also surrounded by four Israeli settlements, making access difficult. The settlements have pushed the villagers from their farmland, a common practice, we’re told. An estimated 90 percent of men age eighteen to thirty-five in Nahalin are unemployed.

The bus chugs to a stop. We exit and walk up a long, steep road of dirt and red rocks, past olive trees and occasional piles of goat dung, the sky a bright blue, the clouds in compact puffs like tanks. The landscape is scrubby and brittle. Two yellow flowers poke from a wall, their stems twisted. On a hill to our left sits a red-roof, white-walled settlement. The settlements are expanding: the clangs of construction crews echo across the valley. In Nahalin, and throughout the West Bank, boxed-in Palestinians expand by building up, since there’s no room to build out. Son gets married? Build a second floor. Another son gets hitched? Build a third floor.

The wind blows as we climb, tossing everyone’s hair. The stone walls are for the olive trees, to help control spring rains and erosion, though given the stark rocky landscape, I’m amazed that it ever rains, or that anything can grow.

Using nearby walls as a model—they stand anywhere from knee to waist high—we stack rocks, making sure one level is solid before stacking on more. Most of the rocks are the size of bowling balls, some smaller, some larger, some flatter; others are boulders that require five of us to move: we strain to flip them from one side to another. A farmer in a New York Yankees stocking cap gives a thumbs-up when we’re done.

An eighty-two-year-old man, skinny but strong, swings a sledgehammer with precision authority, slowly cracking one of the boulders into slabs. Everything about him is wiry and taut: his sledgehammer-like frame; the long, stringy white beard; his ears poking out from a white headdress, which drapes over his shoulder to his orange wool sweater. He is not so much old as ancient; his skin as weathered and parched as the landscape. A fierceness burns in his eyes. He could kick my ass. Without question.

The old man argues with a pudgy Palestinian farmer. They shout over each other in Arabic, pointing, gesticulating.

“The old man thinks the road is too narrow now for cars,” says Habib, part of the Handala team. The argument continues as I sit with Habib on one of the newly completed walls. We eat lunch: pitas filled with bologna and pickles. He’s nice kid, eighteen, upbeat, smart; disheveled hair and glasses on a Ringo Starr nose. A big reader. He taught himself Russian—he visited a friend there—and also speaks English, Arabic, and a little French.

“So I’ve been wondering if most Palestinians dislike Americans,” I say to him. “Well, not so much wondering. I assume you don’t like Americans. It’s more like, how bad is it.”

Since World War II, no country has received more U.S. aid than Israel. In 2009, the United States gave Israel an estimated $7 million a day. We help bankroll everything from the military that harasses Palestinians to the separation wall that screws up their lives. So I’m not expecting him to sing “God Bless America” or the Mickey Mouse Club theme.

Habib chews his bologna sandwich. “It’s not dislike,” he says. “Most people distinguish between the American people and American policy—the American government.”

I ask him where he lives. Hebron, he says.

“Do you go through a checkpoint to get to Bethlehem?”

“Yes, but I don’t always have to stop.”

“What about Jerusalem?”

“I can’t go there.”

“Why—because you need to fill out certain paperwork?”

“Because I’m Palestinian.”

“So you can’t go at all?”

“I can only go if there’s a reason—like family or a job. Sometimes if it’s a religious holiday.”

We finish our lunches, looking out over the brush and the craggy land. Two months from now, on February 25, Habib will be blasted with tear gas. In Hebron and throughout the West Bank, that date is known as Open Shuhada Street Day. The street was closed by the Israelis in 1994 to protect settlers in the city. The closure wounded the local economy; Palestinians struggle to navigate the city. For some a ten-minute walk is now an hour-long commute.

As Palestinians protest in Hebron on February 25—along with some Israelis and international activists—soldiers will fling tear gas canisters into the crowd. Habib will later write to Kayla about the incident:

I was only a few seconds away from being arrested, and am grateful to God I wasn’t shot. I did feel myself like I was swimming in a sea of tear gas, unconscious almost, tired and very dizzy by the gas I just inhaled, just minutes before the soldiers tried to arrest me. I had an onion trying to lessen the effect of gas bombs on my face, eyes and respiratory system. They threw a sound grenade at me, and in my shock I threw the onion at the soldiers, unintentionally. That’s what Newton says in his third law; maybe Israelis should arrest him for discovering that theory. I went away, as far away and as fast as I could, they did want to arrest me, and all I could do is just walk away!

To be honest I was very scared that day. It was the fear of getting shot or arrested, or both, either one is not helpful or good for me. I am a young Palestinian, who loves football, and I also love my country, but I don’t know what my feelings become after such incidents. My feelings toward my country become those of a raged, bitter and scared young man. The feeling that I am constantly in danger, the fear that something bad might happen to me all the time. And it does almost happen every day.

Newton’s third law, in case you’ve forgotten your old science lessons, is that for every action there’s an equal and opposite reaction. But in the messier world of humans, the laws of physics are twisted. For every action the reaction is often twice as severe.

In one of Dad’s late-night writing moments, he took stock of his strengths:

I am: |

I want: |

-Dreamer |

-to be the best |

-Thinker |

-to be loved |

-Sensitive |

-people to remember me |

-Different |

-to contribute |

-Believer in God |

-to make people happy |

-Happy |

-my family to be happy, healthy |

-Giver, not taker |

-to make a difference |

I’m not sure why he did this. Maybe one of the many Stephen Covey–style books he read suggested it. But it’s typical for him. He wanted to be successful. And yet the rest of the list is about happiness, helping others, giving. For all the success he attained, his legacy was never that the company shipped x amount of units or that he improved efficiency or boosted profits. His legacy was the people he supported, the people he inspired. And I think he knew that.

Dad was always close to his cousin Abigail. She was ten when he was born; his family visited her family on their farm most weekends. “Your father was totally at ease with who he was, and I believe he was like that from birth,” Abigail told me at a family reunion after Dad died. “I often rocked him to sleep on those weekends. I would sing hymns to him and he never fought sleep like so many babies do.” She smiled thinking back. “He was always just so comfortable with who he was.”

I always thought I was, too. I thought I knew myself. Now—here—I’m less sure.

I never asked Julie how she felt about me vanishing over Christmas and her birthday. That’s how we are. Part of me thinks it’s not a big deal for her. Part of me thinks, “How can it not be a big deal?” Mom always says, “You two never talk.” She’s right, but I like that about our relationship. We’re comfortable with each other. Sometimes we don’t need to talk. We may be a world apart, but I know she loves me. And she knows, I hope, how much I love her. But I would only realize much later, when I was done traveling, when I fully understood how deeply my introversion had hurt her, that there’s a fundamental difference between knowing you love someone and showing that love. I am guilty of knowing and not showing.

Doug and Kayla are spending the night at the Paradise Hotel on Manger Street to celebrate their wedding anniversary. Doug made the arrangements with Fateen, so it was a total surprise for Kayla. For those of us not spending the night in a hotel with a real bed and a warm curvy human underneath the sheets, Fateen asks us to clean the center.

I mop the floor in the room where we eat our meals. The activity at least warms me up. Before mopping I was shivering, despite a windbreaker and sweater and long-sleeve shirt, despite two pairs of socks. I poured a cup of steaming water, which is meant for tea, just to warm my hands. It always feels colder inside the Handala Center than it does outside on the street, which is where I find Benjamin after we clean. He’s going with Carina, a Spanish volunteer, to talk with a local family for the evening. Several small groups are doing this throughout Beit Jibrin, and I’m thrilled when Benjamin invites me to tag along. We’re escorted by Tariq, a local guy who helps out at the center; he’s one of the family’s neighbors. The few streetlights are dim, the alley graffiti barely visible in the night. The family lives in a ground-floor apartment. Aisha, the mother, smiles, nodding, welcoming us. She leads us to a cramped family room, mauve-and-white-covered love seats against three of the four walls, a table in the middle, matching chair on the other side. A setup conducive to group therapy. A faded painting of a mountain and stream hangs on the wall, like something from a hotel. On a small TV is a soccer game. Palestinian men seem rabid about Spanish league soccer, particularly Barcelona and Real Madrid.

Aisha points at us to sit—her English is limited—then scoots down the hall. On a corner table is a small Christmas tree, maybe three feet high. Later, when Carina comments on the tree, Aisha turns on white lights, which fade on and off. I spot reindeer dishes on a shelf with knickknacks and pottery. I’ve heard that many Muslim families in Bethlehem, like this one, celebrate Christmas. They seem proud of Jesus: he’s the local boy who made good.

Aisha’s husband joins us. He’s not a big man—thin, at least six inches shorter than me, graying hair—but his handshake is as firm as his presence. Aisha brings a pot of Arab coffee on a tray. It’s strong, served in small cups. I haven’t developed a taste for it yet.

“What do you think of al-Azzeh?” the husband asks.

“The people are friendly. They have been very nice to us,” I say, keeping my English clear. “Very warm.”

That’s not what he means. I can tell from his serious eyes. What he means is—

Do you think al-Azzeh is a shithole.

And I’m thinking…

It’s a ghetto.

A not-wholly-unpleasant ghetto—I feel safe walking the streets—but the buildings seem less like homes than factories, bleak and uninspired. Functional.

“Were you scared to come?” he says.

We weren’t, we all say, but our families were. One of the speakers at Handala had talked about the perception of Palestinians as villains, particularly in the United States, pointing to movies like True Lies and The Siege. “Palestinians are not simply Arabs,” he had said. “We’re the worst Arabs.”

My sense is that most Palestinians are baffled by the idea that they’re considered the terrorists. I explain to the husband something I’d noticed before I left home.

“If I told people I was coming to Bethlehem, they’d picture baby Jesus. They’d say, ‘Ohhh, that’s so nice.’ But if I said I was coming to Palestine, or the West Bank, they’d look concerned. A friend of mine asked me if I was bringing a bulletproof vest.”

He asks how Americans view Muslims. I tell him it depends on where you go. You’ll find plenty of Muslims in big cities, but less so in rural areas. I’m reminded of Costa Rica; of the rural Minnesota teenager who asked Jonathan if there were cows in England. She had never met a Jewish person until meeting Hannah, and had never met a Muslim.

“Who did you vote for?” he asks me and Benjamin, referring to the presidential election.

“I didn’t vote for either candidate,” says Benjamin.

The husband nods in approval. “Obama is no different than Bush. He does not care about my people. U.S. soldiers kill people every day somewhere in the world.”

“What about Arab leaders?” says Benjamin.

“Our leaders do nothing. Abbas does nothing. We are weak. Arab nations are weak.”

We pick up a few details about his life. He works for a Palestinian telecommunications company. He was in jail for four years. Benjamin asks why.

“Because I want freedom,” he says. “We live here. We are born here. I want to be free. My people need freedom. My people need a state. We are poor—look here,” he says, raising his arms to the tight room where we’re sitting. “We have no country. My country is a five-minute drive because of the settlements. My country is stone fence to stone fence.”

Aisha has left and returned with a second tray, this one with mint tea and a plate of wafer cookies. I ask her husband if he thinks attitudes will change between Israelis and Palestinians. I tell him about racial attitudes in the American South, that we still have racism, but things have improved radically in the last fifty years.

He seems skeptical. He could accept the 1967 borders, he says, but the Israelis take more land. From his old village, he tells us, he can see the settlements.

“When I was a boy we lived near Jews,” he says. I hear nostalgic variations of this on multiple occasions while I’m here:

Our families helped their families, and their families helped our families.

My grandmother spoke Yiddish because she watched Jewish children in the neighborhood.

This is not an ancient conflict, people like Mahad and Fateen maintain. It dates back to 1948. And the problem, they say, is not Judaism, but Zionism.

The father smokes one of Tariq’s cigarettes. “I respect the Jewish religion,” he says. “I do not respect the Israeli government. What the Nazis did to the Jews was terrible. But what the Jews do to Palestinians is the same as the Nazis.”

He is opposed to Osama bin Laden, he tells us, because bin Laden violates Islamic law by killing innocents. Tariq notes, probably to get a rise out of Carina, that Islam allows multiple wives, but you must treat each wife equally.

“Multiple wives seem like a lot of work,” I say. “I can barely manage one.”

The husband agrees. It is too difficult. “Maybe okay if you have half a wife,” he says.

Aisha has left and come back again, this time with a bowl of oranges. She is pretty, though I’m sure she was prettier once. Her black sweatshirt makes her look frumpy, but in a pleasing way. Her dark hair is uncovered. Carina asks her if she works outside of the home. Tariq translates. She’s a housewife.

“Why are you asking her questions?” the husband asks.

“I want to talk with her because she is so quiet. She hasn’t been here the whole time.”

“She is quiet because she does not speak much English.”

As Carina will note on the walk back to Handala, the husband is left-wing politically—he tells us he’s a socialist, and hails Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez as a freedom fighter (Chávez broke ties with Israel after the Gaza conflict, hence his popularity here)—yet he is clearly conservative when it comes to the roles of women.

Carina asks Aisha what she thinks of Palestinian men. She thinks a moment while peeling oranges.

“Rubbish,” she says—and she throws her head back and laughs. We all laugh. We talk and talk—the husband sits with his thin legs crossed, smoking another cigarette—discussing everything from the Iraq War to housework, realizing eventually that it’s after midnight.

“You are always welcome in my home,” the husband tells us. “I open my home to you.” It turns out Aisha has a relative who studied in New Jersey.

“I have a friend in New Jersey,” I tell them of Hannah.

They escort us to the door and we return to the stark street, trash blowing as we walk, plastic bottles skipping and rolling against our feet. A night like this, I decide, is why dialogue is so important. Because a Palestinian may have softened his views of the United States. And an American gained insight on what it’s like to be a Palestinian. That has to be worth something.

Burt the bearded Belgian is in striped cotton briefs, his butt about four feet from my face. He’s bending over, skinny pale legs extending from his underpants, looking for socks. Burt is a sweet, gentle man, though seeing his striped-cotton middle-aged behind is not my preferred way to start the day, and on this morning it’s literally the first thing I see. Granted, we’re in such close quarters that Burt has surely endured an equally unpleasant view of my ass in not nearly as festive briefs. There’s no space between Burt’s sleeping bag and my sleeping bag and Mike’s sleeping bag and Emmanuel’s sleeping bag, which is stretched behind our heads. I lie closer to them than I do to Julie in our bed back home.

I look away from Burt’s ass, staring up at paint peeling from the ceiling in strands, the single lightbulb hanging. Mike, the college-age Brit, sits up bleary, resting on his elbows.

“It’s starting to smell like eighteen guys in here,” he says in a croaking morning voice.

I unzip my bag, get up, put on jeans, and step over Mike to slide open the window, so we can air out the room with the fresh smell of … goats. The family living behind our building has a few farm animals.

“A few more days and the goats will be complaining about us,” I tell Mike.

Doug has smartly moved to the flat next door, deciding he couldn’t take two weeks trapped between the Italian snorers, though space is equally tight in his new digs. He’s sleeping in the only spot he could find: partially under Habib’s bed, his legs below, chest and head sticking out the other side.

“Funny how that’s a step up from where I was,” he says.

Bruno is such an impressive snorer—it starts within minutes of closing his book each night—that a few guys from the bigger room come in at night to listen and observe.

“It’s like having a vibrating bed,” I tell them.

At breakfast I ask Doug and Kayla about their night at the Paradise Hotel. Turns out the hotel’s owner, Joshua, lived just a few blocks from them in Philly. He joined Doug and Kayla for a drink. “The biggest mistake I ever made was coming back to Bethlehem,” he told them over a cup of Nescafé. Bethlehem is his hometown; he moved back because the West Bank, at the time, seemed peaceful. But then came the Second Intifada. And the wall. And the checkpoints.

“They make life hard,” he said. Last winter, the hotel was booked from before Christmas to after New Year’s. Then the fighting began in Gaza. Joshua lost nearly one hundred thousand dollars in canceled bookings. This year business has improved due to the relative stability, but he plans to sell the hotel in two years, when his son is ready for college, and move back to the States.

“He doesn’t think things will get better, even though he’s relatively privileged,” Kayla writes in a blog for family and friends. “He told Doug, ‘Don’t tell your coworkers about the boycott. Don’t bring up the Palestinians—nothing good comes from it.’ He was so adamant about it.”

We eat breakfast, then walk to the morning’s volunteer gig: a two-story building near the Aida camp that’s being converted into a youth and cultural center. Palestinians are building such centers to preserve their traditions, from music to architecture to folklore. A brown wood-grained archway shaped vaguely like a keyhole stretches from one side of the street to the other. Sitting on top is a giant black key—“the largest key in the world,” says Mahad. The key, he tells us, is a powerful symbol to Palestinians: when families were forced from their homes, they had minutes to grab essentials—money, photos, and, in many cases, their keys, since they expected to be back soon. Those keys are now family heirlooms.

The building has been gutted. In front is a concrete barrier; on it someone has spray-painted their desire for freedom. We go to the second floor. The steps are gone; it’s more like a split-level concrete ramp with two-by-fours for traction. Wind whips through large square holes where windows will eventually be. Cinder blocks are stacked in mounds. A few of the Irishmen pound the jagged remains of a concrete wall with jackhammers, debris ricocheting off of walls (someone says they’re using the wrong type of bit). The rest of us form a bucket line to dispose of rubbish that piled up during the gutting process: chunks of cinder blocks, tile, swept-up gray dust, pieces of wood, and wires, which we dump from a balcony into the bed of an orange dump truck below.

The two young Italian guys, who seem like lifelong friends but met right before coming here, sing “Bella Ciao”—Goodbye, Beautiful—an antifascist resistance tune from World War II. It’s a catchy little ditty, and everyone sings as we work—

O bella ciao, bella ciao, bella CIAO, CIAO, CIAO!

Dust rises from the crash of debris in the truck bed below. My coat is covered, my sunglasses caked; I can feel the dust in my eyes. The truck gets full, rumbles off to dump the trash, then returns. The process starts again.

After a few hours, we walk back to Beit Jibrin for lunch, passing one of the more striking graffiti paintings in Bethlehem: it’s a soldier, viewed from behind—hands against the wall—frisked by a little girl in a dress. On another wall is a dove with an olive branch in its mouth, a gun-scope target on its breast. I never see billboard-type ads for products—for cereal or soda or cell phone service. The most-advertised products are cynicism, frustration, harassment.

We take a shortcut between apartment buildings, snaking through trench-like alleys. “Bullet holes,” says Habib nonchalantly, pointing at some pipes.

Later he notes some red and green graffiti in Arabic.

“It means ‘freedom.’ I know who did this—he’s in prison.”

We enjoy a takeout lunch at the Handala Center: roasted chicken with yellow rice and nuts in Styrofoam boxes. As we eat, Mike and Peter, another Brit, say that a week before we arrived, Fateen was stabbed in the leg during a soccer game. Fateen fouled a guy—hard—and apologized. The guy was pissed. “So Fateen tells him, ‘If you won’t accept my apology, and you don’t want to get hurt, don’t play.’ And the guy pulled a knife and stabbed him,” says Mike.

“I wonder if the guy got a yellow card,” Peter quips.

“It was a red card,” says Mike. “It was covered in blood.”

I’m a little bloody myself. I cut my fingers today while dumping cinder blocks and other debris into the Dumpster. There’s blood on my jeans, my coat, my canvas bag.

“I’m amazed no one’s been hurt yet,” says Peter.

“Think of that construction site,” says Mike. “No masks for the dust, no hard hats, volunteers using jackhammers, we’re dropping debris while people are working underneath…”

“Apparently a few locals and UN people complained about the dust.”

The United Nations Relief and Works Agency operates a school next to the building we were cleaning out, and has offices there as well. Each camp is served by a UNRWA office: the UNRWA handles services a municipality might normally provide, from trash to water to clinics.

“Yesterday at the olive farm I kept getting hit by rocks—this eighty-two-year-old guy was pounding boulders with a sledgehammer and stuff was flying,” I say. “Maybe it’s part of the fatalism here. Why wear safety goggles given all the other shit that’s going on?”

“That’s probably why they all smoke,” says Mike.

Mike and Peter also visited a family last night. They asked the family what they do for fun on weekends.

“They said, ‘We don’t do anything for fun,’” says Peter. “They just live day to day and see what happens. They don’t plan ahead.”