One of the few photographs of the Halifax Explosion. Photograph: Library and Archives, Canada.

A German chemist who worked on designing poison gas in World War I and who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1918 for his work on nitrates, Fritz Haber was born on December 9, 1868, at Breslau, Germany (modern-day Wroclaw, Poland). Both his parents were Jewish. His father, Siegfried Haber, was a well-known merchant in Breslau, and his mother, Paula, died when he was a child. Haber was educated at the University of Heidelberg, where he studied under Robert Bunsen, and he then went to the University of Berlin where he worked with A. W. Hofman. He then went to the Technical College of Charlottenburg (now the Technical University of Berlin), where he studied under Carl Liebermann. On leaving the university, Haber worked at his father’s business developing chemicals.

From 1894 until 1911 Haber worked in Karlsruhe, where he and Carl Bosch developed what became known as the Haber process. This involved using high temperatures and high pressure to lead to the catalytic formation of ammonia from hydrogen and atmospheric nitrogen. After this, Haber went to Zurich, Switzerland, where he worked with Georg Lunge at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology. From 1911 until 1933 most of his research took place at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physical and Electrochemistry at Berlin-Dahlem.

During World War I, Haber was active in working on aspects of chemical warfare. He developed the gas mask, which had absorbent filters. He was also involved in developing chlorine gas and other gases that were used against Allied trenches on the Western Front. Much of his research was pitted against that of Victor Grignard, the French Nobel laureate for Chemistry in 1912.

Haber married Clara Immerwahr in 1901, and they had a son, Hermann, born in the following year. After Haber started developing poison gases for war, including overseeing the first successful use of chlorine gas on April 22, 1915, at the Second Battle of Ypres, Clara tried to get her husband to stop this work. She was also a chemist and was appalled at the use of his knowledge in war. She committed suicide by shooting herself on May 15, 1915, with Haber leaving for the Eastern Front that same day to supervise the release of poison gas against the Russians. Haber quickly noticed that death resulted either from exposure to a high concentration of gas for a short time or exposure to a low concentration over a long time. He used these to create Haber’s Rule, a mathematical relationship between the concentration and the exposure.

In 1918 Haber was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his role in the Haber process—the prize had been reserved in 1916 and 1917. The Haber process was a major advance in industrial chemistry as it helped with the production of many nitrogen products that were used as fertilizers, explosives, and chemical feedstock. Production before had been from natural deposits of sodium nitrate, of which much of the world’s supply came from Chile. The availability of cheaper fertilizer helped lead to an increase in food production, and some credited Haber with averting a possible worldwide food shortage because of the rapid increase in the population. Some pessimists had even suggested what amounted to a Malthusian catastrophe, based on the predictions of Thomas Malthus, by which the increase in population would rapidly outstrip the supply of food.

Subsequent to his winning the Nobel Prize, Haber researched into various combustion reactions, including the separation of gold from seawater, and he published some papers on the topic. However, he ended his research in this field, concluding that the concentration of gold in seawater was much lower than some earlier scientists had suggested. He also worked on various absorption effects and aspects of electrochemistry. Although Haber had been much criticized for his work on poison gas in World War I, he had defended it by claiming that death was the same however it was inflicted. In 1932 Haber was awarded the Rumford Medal of the Royal Society.

With the rise in anti-Semitism in Germany, Haber converted to Christianity. By this time he had remarried. However, this did not prevent persecution when the Nazi Party came to power. He left Germany and went to Cambridge, England, where he worked for a few months. He then considered taking up a position at the Weizmann Institute in Rehovot in the Palestine Mandate. However, on January 29, 1934, Haber died from a heart attack while staying in a Basel hotel in Switzerland. He was cremated, and his ashes, as well as those of his first wife, were interred at the Hornli Cemetery in Basel. His second wife, Charlotte (née Nathan), whom he had married in 1917, and their two children, Ludwig “Lutz” and Eva, settled in England, with Hermann, his son by his first marriage, immigrating to the United States and committing suicide in 1946. Lutz Fritz Haber, one of his two surviving children, became a historian and in 1986 wrote The Poisonous Cloud, which was a history of chemical warfare in World War I. His daughter, Eva Lewis, has been interviewed several times about the role her father played in World War I.

—Justin Corfield

Further Reading

Charles, Daniel. Master Mind: The Rise and Fall of Fritz Haber, the Nobel Laureate Who Launched the Age of Chemical Warfare. New York: Ecco, 2005.

Goran, Morris. The Story of Fritz Haber. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1967.

Haber, Lutz Fritz. The Poisonous Cloud: Chemical Warfare in the First World War. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986.

Hogg, I. V. Gas. New York: Ballantine, 1975.

Langer, W. L. Gas and Flame in World War I. New York: Knopf, 1965.

Szöllösi-Janze, M. “Pesticides and War: The Case of Fritz Haber.” European Review 9 (2001): 97–108.

The Halifax Explosion occurred on December 6, 1917, at the harbor of Halifax, Nova Scotia. The harbor was bustling with activity as World War I brought increased demands for shipping to and from the harbor. Two ships collided, and one, a French ammunition ship, the Mont-Blanc, caught fire and exploded. The resulting explosion destroyed property, including schools and homes, for miles around and left approximately two thousand dead and nine thousand more injured. It was the most devastating man-made explosion in history until the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima.

Halifax harbor and the surrounding areas had grown thanks to international demand due to the First World War. Ships from Allied and neutral nations alike docked at the harbor to take on supplies ranging from food and clothes to weapons and ammunition. Canadian troops and supplies bound for the Western Front also embarked at Halifax. Many ships headed for Europe formed convoys just out of the harbor for mutual protection during the Atlantic crossing. The rapid increase in activity also brought needed supply businesses to the area, such as increased warehouses, railroads, stores, and military facilities. A general population boom accompanied these industries.

The biggest drawback to this influx of shipping activity was that the Narrows, the shipping lane that separated Halifax and Dartmouth, was not large enough to handle the amount of traffic, especially given the confusion and lack of regulation on ships coming and going. The French Mont-Blanc left port on the morning of December 6, 1917, loaded down with explosives that included two hundred tons of trinitrotoluene and other incendiary devices. Very soon, the Mont-Blanc collided with the Imo, a Norwegian vessel also trying to navigate the Narrows. The Mont-Blanc caught fire, and her crew abandoned ship and rowed to the Dartmouth side. The unmanned ship, now on fire, floated back toward Halifax. It came to rest at Pier 6, where people watched the vessel burn. Just after 9 a.m. the Mont-Blanc exploded, leveling structures for miles around and killing nearly two thousand people and wounding nearly nine thousand others. The blast created a mushroom cloud filled with debris that covered the city. The explosion also created large waves that swamped vessels and poured into the city. After the immediate effects of the explosion subsided fires spread throughout Halifax. Many were killed from the blast outright, while others were killed from glass and wood shrapnel and other debris sent flying by the destroyed homes, businesses, churches, and schools. The harbor and many of the docked ships, some already loaded with men and supplies, were also destroyed.

Loss of life was mitigated by the rapid organization and response of relief agencies that included the military and rescue workers already stationed at Halifax, with support from across Canada and from the United States. Supplies poured in immediately, and empty ships and buildings were quickly converted to makeshift hospitals. Hospitals in nearby towns took in as many of the wounded as they could while relief agencies and civilians helped clean up and house those who now found themselves homeless. In the immediate aftermath many thought that the Germans had caused the explosion. Once the true cause had been discerned, charges were brought against both ships. Ultimately no criminal charges were levied, and it was declared an accident. There are several monuments and museums created as a memorial to those that died in the explosion. Another lasting reminder is that the people of Halifax donate a large Christmas tree to the city of Boston as a continued thanks for their help during the relief efforts following the explosion.

One of the few photographs of the Halifax Explosion. Photograph: Library and Archives, Canada.

See also: Anarchism; Bhopal Catastrophe; Chernobyl Nuclear Power Station; Factory System; Great Chicago Fire of 1871; Haymarket Affair; Seveso Disaster; Texas City Disaster; Three Mile Island; Times Beach, Missouri, Disaster; West Fertilizer Company Explosion (2013).

—Antonio Thompson

Further Reading

Armstrong, John Griffith. The Halifax Explosion and the Royal Canadian Navy: Inquiry and Intrigue. Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada: University of British Columbia Press, 2003.

Flemming, David. Explosion in Halifax Harbour: The Illustrated Account of a Disaster That Shook the World. Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada: Formac Publishing, 2004.

Mac Donald, Laura M. Curse of the Narrows. New York: Walker and Company, 2005.

Mildon, Catherine M. Exploded Identity: A Saga of the Halifax Explosion. Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada: Crown Publishing, 2004.

Hall, Charles Martin (1863–1914)

An American inventor and engineer, Charles Martin Hall became well known for his process for the production of aluminum. His electrolytic process for the cheap extraction of aluminum resulted in it becoming far cheaper than it had been beforehand and ensured that aluminum would become the first new metal to gain widespread use in the world since the prehistoric discovery of iron.

Charles Martin Hall was born on December 6, 1863, at Thompson, Ohio, the son of the Reverend Herman Bassett Hall and Sophronia (née Brookes). Herman Bassett Hall was from Vermont and Sophronia was from Ohio. There were two sons and five daughters in the family—Ellen J., Emily B., Julia B., Charles Martin, Edith M., and Louisa A. Hall—and they moved to Oberlin, Ohio, in 1873. Charles Hall attended Oberlin High School, and in 1880 he went to Oberlin College, a selective liberal arts college, from where he graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1885. Since he was young, Martin had been interested in scientific experiments. One of the men who encouraged him was Frank Fanning Jewett, a professor of chemistry whose home is now preserved as the Oberlin Heritage Center. In it there is a re-creation of the woodshed experiment that Hall made in 1886. The original Hall family house is also preserved but the woodshed is no longer there.

On February 23, 1886, Hall was able to produce the first samples of aluminum after having worked on it for several years. Helped by his older sister, Julia Brainerd Hall (who had also studied under Jewett), the method was essentially to pass an electric current through a bath of alumina that had been dissolved in cryolite. Recent scholarship suggests that she may have been crucial in this experiment. This resulted in the formation of deposits of aluminum in the base of the retort. On July 9, 1886, Hall filed for his first patent, narrowly beating the French scientist Paul Héroult. In 1893 the U.S. courts accepted that Hall had invented the process first, giving him “priority of invention.” However, the process is still often called the Hall-Héroult process.

Initially failing to find backing for the project in Ohio, Hall went to Pittsburgh, where he combined his resources with the metallurgist Alfred E. Hunt. Together they established the Reduction Company of Pittsburgh, and they built the first large-scale aluminum plant, starting the first commercial manufacture of aluminum in 1888. This manufacture reduced the price of aluminum to 0.5 percent of its previous price, making it cheap enough to use for a vast number of extra uses and to make its use very common around the world. It became one of the most common nonferrous metals used in the world. The company was subsequently renamed the Aluminum Company of America, and it is now called Alcoa. As a major holder of stock in the company, Hall became very wealthy, and by 1900 annual production levels reached eight thousand tons. He gained his master’s degree from Oberlin College in 1893, with a doctorate in law in 1910.

Refining the process, Hall continued researching and fine-tuning his inventions for the rest of his life, and in total he received twenty-two U.S. patents, most of which were on the production of aluminum. In 1890 Hall became vice president of Alcoa, a position he held for the rest of his life, and he also served on the Oberlin College Board of Trustees. In 1911 Hall was given the Perkin Medal, the highest award for industrial chemistry in the United States.

Charles Martin Hall lived at Niagara Falls in New York, and in the 1900 census he described himself as “vice-president, factory.” He died on December 27, 1914, at Daytona, Florida, and he was buried at the Westwood Cemetery in Oberlin. He was unmarried. In his will, proven after his death, he donated large sums of money to Oberlin College, and a statue of him—appropriately made in aluminum—was unveiled at the college. It was moved many times and is now on a large, granite block on the second floor of the new science center at the college. In 1997 the production of aluminum by electrolytic process was designated as a National Historical Chemical Landmark by the American Chemical Society.

Charles Martin Hall

The company, Alcoa, is now the third largest producer of aluminum in the world, with its principal headquarters in New York and its operational headquarters at Pittsburgh. In 2006 it employed 129,000 people, with a revenue of U.S. $30.4 billion and a net income of U.S. $2.248 billion.

See also: Mining.

—Justin Corfield

Further Reading

Craig, Norman C. “Charles Martin Hall—The Young Man, His Mentor and His Metal.” Journal of Chemical Education 63, no. 7 (1986): 557–59.

Craig, Norman C., and Christian M. Bickert. “Historical Metallurgy: Hall and Héroult—The Men and Their Invention.” CIM Bulletin 79, no. 892 (1986): 98–101.

Trescott, Martha M. “The Story behind the Story: Julia B. Hall and Aluminum.” Journal of Chemical Education 54, no. 1 (1977): 24–25.

Hall, Lloyd Augustus (1894–1971)

An African American chemist who contributed much to the science of food preservation, especially in the curing and preservation of meat for sale in supermarkets and elsewhere, Lloyd Augustus Hall transformed the nature of the food industry in the United States, and also the world. It was probably one of the most important developments in preserving food since refrigeration. He was born on June 20, 1894, at Elgin, Illinois, the son of Elisha A. Hall and Isabel (née French). His grandfather was one of the first Baptist preachers in the area, and his father was a Baptist minister at the same church. Lloyd Hall attended the high school in Aurora and then studied chemistry at Northwestern University, graduating with a bachelor’s degree, and then he worked as a chemist at the Department of Health Laboratories in Chicago, becoming a senior chemist in 1917 and briefly attending the University of Chicago as a graduate student.

With the start of the U.S. involvement in World War I and the United States sending soldiers to France, Hall was commissioned as lieutenant and worked as assistant chief inspector of powder and explosives at the Ordnance Department. Facing discrimination in the army, Hall put in for a transfer, and over the next nine years he worked at a number of chemical laboratories, often as a consultant. His first work was as the chief chemist of John Morrell & Co., Ottumwa, Iowa, in 1919 to 1921, and then at the Boyer Chemical Laboratory Company in Chicago in 1921. He was president and chemical director of the Chemical Products Corporation of Chicago in 1922 to 1925. In 1925 he was hired by Griffith Laboratories to work on food science, devoting much of the rest of his career to this. He remained at Griffith as chief chemist and director of research until 1946 and was technical director from 1946 until 1959. He remained connected with the company as a consultant after then.

Hall’s first major work was to try to cure meat, especially to improve the system known as “flash-drying,” which was used by Griffith Laboratories. It had been originally devised by a German chemist named Karl Max Seifert, who used solutions of sodium chloride and a number of secondary salts that were sprayed on hot metal and then dried quickly. This led to the production of crystals of the secondary salts, which were encased in the shell of sodium chloride. In 1934 Seifert had patented the process and sold the rights to Griffith Laboratories.

Enoch L. Griffith, the owner of Griffith Laboratories, was keen on using this process to cure meat. He felt that the use of nitrates and nitrites might also work to achieve this. Hall helped develop and improve the system and never claimed to have invented it, despite this appearing in many books and newspaper articles. However, he certainly took a major role in the development of meat curing by adding hygroscopic agents such as corn sugar and also glycerine to inhibit the caking of the powder. As a result, most of Hall’s patents in meat curing are concerned with attempts to prevent the caking of curing composition or remedying the ill effects that are caused by anticaking agents.

Lloyd Hall was also heavily involved in investigating the role that spices have in the preservation of food. It had already been discovered that some seasonings had a natural antimicrobial property. Hall researched along with Carroll L. Griffith, and they discovered that some spices also contained bacteria as well as spores from yeast and some molds. To counter the ill effects of the bacteria and mold, Hall and Griffith patented a method of sterilization of spices in 1938. This involved exposing the food to ethylene oxide gas, which is still used as a fumigant. In fact, ethylene oxide gas was used in many countries until recently, when health concerns led to its use on food being banned in the European Union and in Japan. However, it is still used to treat and sterilize medical equipment.

Over many years Hall studied the effects of antioxidants to prevent the spoiling of food, which was common with the rancidity of fats and oils. Unprocessed vegetable oils included natural antioxidants such as lecithin, which slowed spoilage. Hall developed ways to combine these compounds with salts and other materials.

Writing extensively on many topics connected with his work, Hall was the assistant editor of Beta Kappa Chi Journal in 1948 to 1949 and editor of The Vitalizer, published by the Chicago section of the Institute of Food Technologists in 1948. He was consultant editor for the next two years. He was also a member of the editorial advisory board of Food Processing magazine from 1952 until 1956, and a member of the advisory board of Chemical and Engineering News in 1957 to 1960. Hall was also a member of many social and community organizations, including being on the advisory board of the Los Angeles State College, the YMCA movement, as well as the Kenwood Neighborhood Redevelopment Corporation.

During World War II, Hall was a member of the scientific advisory board of the Commission on Food Research at the War Department, 1943 to 1948. Retiring from Griffith Laboratories in 1959, Hall took up a position as a member of the research advisory board at Truesdail Laboratories Inc., from 1960. Hall was a consultant for the Food and Agriculture Organization, and from 1962 until 1964 he was a member of the American Food for Peace Council. Hall was a member of many intercollegiate fraternity organizations, including Alpha Phi Alpha, the first Greek-letter fraternity established for African Americans. He retired to Altadena, California, and died on January 2, 1971, at Pasadena, and was buried at the Forest Lawn Cemetery in Glendale, California.

—Justin Corfield

Further Reading

Brodie, James Michael. Created Equal: The Lives and Ideas of Black American Innovators. New York: W. Morrow, 1993.

Kessler, James H., J. S. Kidd, Renée A. Kidd, and Katherine A. Morin. Distinguished African American Scientists of the 20th Century. Phoenix, AZ: Oryx Press, 1996.

Halliburton Energy Services is a large, U.S.-based multinational corporation that operates in more than 120 countries in the world. It has extensive political ties in the United States and has been at the forefront of criticism from media organizations around the world, mainly over its role in the invasion of Iraq in the Gulf War (2003). It is often used as an example of the military-industrial complex, and the profits made by Halliburton are criticized by commentators and journalists around the world.

The company was established by Erle Palmer Halliburton (1892–1957) and his wife, Vida (née Taber), who were involved in the cementing of oil wells in Burkburnett, Texas, later moving their business, then called the New Method Oil Well Cementing Company, to the Healdton Field near Ardmore in Oklahoma. Erle Halliburton was born in Tennessee, and his wife was from Illinois. Erle worked as an oilfield worker in California before moving to Texas as a consulting engineer.

In 1920 the company was reorganized and became the Halliburton Oil Well Cementing Company, and in the following year it moved its headquarters to Duncan, Oklahoma, and was incorporated in 1924. Erle Halliburton was the president and general manager from 1920 until 1947 when he became the chairman of the Board of Directors. In 1948 the company was listed on the New York Stock Exchange. In 1957 it acquired the Welex Jet Services of Fort Worth, Texas, and three years later it shortened its name to Halliburton Company, moving its headquarters to Dallas, Texas, in the following year.

Halliburton Company gradually increased in size with the acquisition of Brown & Root of Houston, Texas, in 1962. By 1982, with the energy industry in decline, it already employed 115,000 workers, and in 1988 it diversified, buying Geophysical Service Incorporated from Texas Instruments and establishing Halliburton Logging Services in the same year. It also bought Gearhart, but the downturn in the economy meant that it had a workforce of about seventy-three thousand in 1991.

After the Gulf War (1991), crews from Halliburton were involved in bringing 320 burning oil wells under control. At about the same time Dick Cheney, the U.S. Secretary for Defense, paid Brown & Root Services more than $8.5 million for them to undertake a report on behalf of the Pentagon to study the possible use of private military forces to serve with U.S. military personnel in combat zones. By this time Halliburton itself was involved in a number of scandals. One was over Halliburton Logging Services selling six-pulse neutron generators to Libya in violation of U.S. federal sanctions, and Halliburton had also sold dual-use oil drilling equipment to both Libya and Iraq in violation of U.S. federal regulations. In 2001, in spite of U.S. sanctions against Iran, the Wall Street Journal reported that a company called Halliburton Products and Services Ltd., incorporated in the Cayman Islands but using the logo of Halliburton Energy Services, had an office in Tehran. As no U.S. citizen was employed at the office and the company was officially registered in the Cayman Islands, it did not violate the Trading with the Enemy Act, which had been enacted in 1917 and was still in force.

In 1995 Thomas H. Cruikshank, who had been chairman and Chief Executive Officer of Halliburton since 1989, was replaced by Dick Cheney, the former Defense Secretary. In 1998 Halliburton merged with Dresser Industries, and one of the directors of Dresser, Prescott Bush, became a director of Halliburton. These close business links between Cheney and the Bush family have been the center of the controversies that have dogged the company since then. In 2001 Cheney became U.S. vice president, and subsequently Halliburton and its subsidiaries have been involved in major U.S. government contracts.

With the wars in the Balkans in the 1990s, Halliburton had been involved in providing services to the U.S. peacekeeping forces there, including food, laundry and transportation. They expanded their role in the Gulf War (2003), which led to the invasion of Iraq. Halliburton had been asked to draw up contingency plans in case of fires in the Iraqi oil wells and also to secure the oil wells and get them ready for production after a U.S. invasion.

After the U.S. invasion of Iraq, in which a significant amount of the Iraqi government infrastructure was destroyed, Halliburton was involved in much of the reconstruction work. They managed to get the oil pipelines working again, although they faced many problems emerging especially from the deterioration of the security situation in the country. The Halliburton contracts in Iraq generated some $13 billion in revenue, with higher figures quoted when Halliburton subsidiaries are included. The actual profit margin remained low, sometimes as low as 2 percent, unlike their core energy business that was far more profitable in percentage terms. However, there have been many persistent allegations of Halliburton inflating the costs of their operations in Iraq, with audits by various government bodies and private companies showing some “questioned costs.” Much has been made of this—and also the connections between Dick Cheney and Halliburton—in investigative reports published in newspapers around the world, and in television documentaries either about Halliburton specifically or about the military-industrial complex in general. In April 2004 Halliburton became the only company directly referred to by Osama bin Laden because of the profits made in Iraq.

Halliburton currently employs fifty thousand people around the world, and maintains its headquarters in Houston, Texas. It has a second headquarters in Dubai, in the United Arab Emirates, where Halliburton’s chairman and CEO David J. Lesar lives and works.

—Justin Corfield

Further Reading

Briody, Dan. The Halliburton Agenda: The Politics of Oil and Money. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2004.

Bryce, Robert. Cronies: Oil, the Bushes, and the Rise of Texas, America’s Superstate. New York: Public Affairs, 2004.

Juhasz, Antonia. The Bush Agenda: Invading the World, One Economy at a Time. New York: Regan Books, 2006.

Hamilton, Alexander (1755/1757–1804)

Alexander Hamilton was, over the course of his life, an army officer, lawyer, Founding Father, politician, statesman, financier, and political theorist. He was a leader in calling for the Constitutional Convention of 1787, and he was one of the two chief authors of The Federalist Papers. He was also one of the founders of the Federalist Party, but his greatest contribution was the creation of the banking and financial system that allowed the new nation to survive and his recognition that eventually commerce and industry would be the foundations of the American economy.

Hamilton was born in Nevis, in the West Indies, in 1755 or 1757. As a youth, he showed great intellectual promise, and in 1772 he was sent to the colonies by a benefactor to complete his education. He graduated from Kings College, later Columbia University, and while there he became involved in the revolutionary movement.

During the Revolutionary War, Hamilton served as aide-de-camp to George Washington, who later appointed him the first Secretary of the Treasury. In this position he became a close confidante of Washington and exerted great influence over the direction of policy during the formative years of the U.S. government. He believed in the importance of a strong central government and persuaded Congress to use the “necessary and proper,” or elastic clause of the Constitution, to pass far-reaching laws. These included the funding of the national debt, federal assumption of the state debts, the creation of a national bank, a system of taxation involving tariffs on imports, and excise taxes.

Hamilton was one of the founders of the Federalist Party, the first American political party, which he built up in the 1790s using Treasury Department patronage, networks of elite political leaders, and aggressive newspaper editors. His primary political adversary was Thomas Jefferson, who, with James Madison and others, created the opposition party that came to be known as the Jeffersonian Republicans. They opposed the ideas of a strong central government and attempted, without much success, to block all of Hamilton’s plans.

At the end of the Revolutionary War in 1783, Hamilton served for a short time in the Continental Congress and then opened his own law office in New York City. He was successful, and in 1784 he founded the Bank of New York, which today is the oldest bank in the country. In 1786 he attended the Annapolis Convention and drafted the resolution calling for a Constitutional Convention. He was one of three delegates from New York to the convention, but he had little influence there because the other two delegates were opposed to the creation of a strong central government.

Although he had reservations about the first draft of the Constitution, thinking it did not create a strong enough government, Hamilton became a leader in the campaign for ratification. Along with John Jay and James Madison, he wrote a masterful defense of the Constitution now known as The Federalist Papers. The work consists of eighty-five essays, of which Hamilton wrote fifty-one, Madison twenty-nine, and Jay five. These essays were influential in bringing about the successful ratification of the Constitution.

Hamilton served as Secretary of the Treasury from 1789 to 1795. Early in his term of office, in 1790 and 1791, he submitted five reports that laid the groundwork for a financial revolution in the American economy. These reports were: First Report on Public Credit (January 14, 1790), Operations of the Act Laying Duties on Imports (April 29, 1790), Second Report on Public Credit (December 14, 1790), Report on the Establishment of a Mint (January 28, 1791), and Report on Manufacturing (December 5, 1791).

All of Hamilton’s proposals became bases of policy, except the Report on Manufacturing, which was shelved by Congress. It was nevertheless important historically because it presented a clear vision of the dynamic industrial economy that would one day develop in America. There was significant debate, but as for his other proposals Congress soon passed legislation providing for the assumption of the states’ debts, the funding of the national debt, the creation of a national bank, the creation of a mint, and an elaborate system of duties, tariffs, and excises. In less than five years, Hamilton had replaced the fragmented and chaotic financial system of the Confederation period with a modern and stable system that gave investors the confidence to invest in government banks. But there was opposition. Jefferson and Madison believed that Hamilton’s plans stretched the meaning of the Constitution, and as leaders of the newly created Republican Party, they defended the idea that the Constitution should be interpreted narrowly to prevent the federal government from becoming too powerful. There was also violent opposition. Farmers in western Pennsylvania, who derived most of their income through the sale of whiskey, rebelled against the excise tax in 1794 hoping to force its repeal. But the government sent a strong military force to the area and put down the so-called Whiskey Rebellion with little bloodshed.

After leaving public office in 1795, Hamilton continued to practice law and remained involved in local, state, and national politics. His outspoken nature and fiery temper often caused him trouble, and finally he was challenged to a duel by Vice President Aaron Burr. Burr wanted to run for governor of New York, but he was challenged by Hamilton, who referred to him as a man not fit for the office. Stung by the insult, Burr demanded satisfaction, and on July 12, 1804, he shot and killed his adversary.

Alexander Hamilton set a precedent as a cabinet member, developing federal programs, writing them up in report form, pushing for their approval by appearing in person to defend them on the floor of Congress, and then implementing them. His interpretation of the Constitution, especially of the “necessary and proper clause,” laid the foundation for the later growth of a strong and activist federal government.

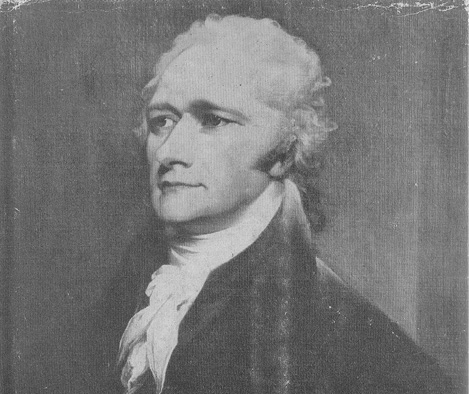

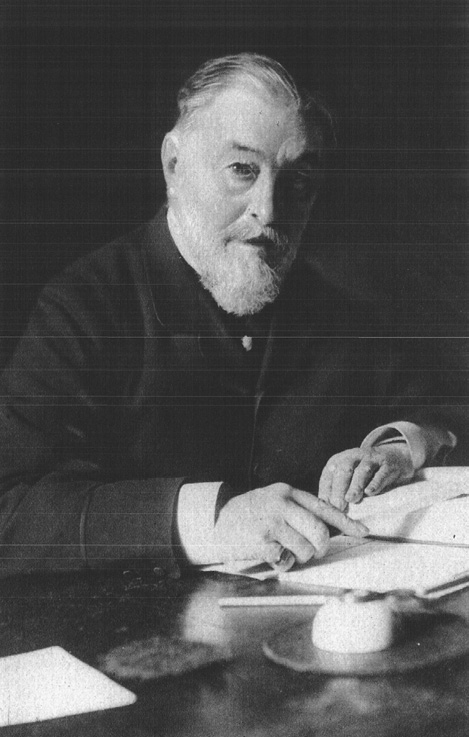

Alexander Hamilton, portrait by John Trumbull.

See also: American System (American School of Economics); Bank of the United States; Democratic Party; United States.

—Kenneth E. Hendrickson Jr.

Further Reading

Brookhiser, Richard. Alexander Hamilton: American. New York: Free Press, 1999.

Chernow, Ron. Alexander Hamilton. New York: Penguin Books, 2004.

Ellis, Joseph J. Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation. New York: A. Knopf, 2002.

Fleming, Thomas. Duel: Alexander Hamilton, Aaron Burr and the Future of America. New York: Basic Books, 2000.

Flexner, James. T. The Young Hamilton: A Biography. New York: Fordham University Press, 1999.

Hammond, John Lawrence Le Breton (1872–1949)

An historian and journalist, he was born on July 18, 1872, at Drighlington, Yorkshire, England, the second of the eight children of Vavasour Fitz Hammond Hammond, the local rector, and his wife, Caroline (née Webb). Growing up in the village of Drighlington, close to both Bradford and Leeds, John grew up in a household where his father was a supporter of the British prime minister William Ewart Gladstone. Educated at Bradford Grammar School, he proceeded to St. John’s College, Oxford, where he was known for his radical views. Elected secretary of the Oxford Union in November 1894, he worked for Sir John Brunner, the Liberal member of parliament for Cheshire. He started writing, and in 1901 he married Lucy Barbara Hammond, the seventh and youngest child of Reverend Edward Henry Bradby, the headmaster of Haileybury College, and who had studied at Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford.

The Hammonds lived in Hampstead, London, and then moved to a farm near Hemel Hempstead, Hertfordshire. Lawrence Hammond joined the Royal Field Artillery in World War I. However, he soon left, and with his wife, the couple continued writing. In 1911 they had written The Village Labourer, and this was followed by The Town Labourer (1917), then The Skilled Labourer (1919). They wrote a biography, Lord Shaftesbury (1923), and then The Rise of Modern Industry (1925). The three books on laborers and their other books soon became some of the best-known works on English rural history and the period of the Industrial Revolution. Lawrence Hammond also wrote for the Manchester Guardian. He died on April 7, 1949, and his wife died on November 16, 1961.

—Justin Corfield

John Hammond’s book, The Town Labourer, published by the Left Book Club.

Further Reading

Clarke, P. Liberals and Social Democrats. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978.

Weaver, Stewart A. The Hammonds: A Marriage in History. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1997.

———. “Hammond, (John) Lawrence Le Breton (1872–1949).” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. London: Oxford University Press, 2004.

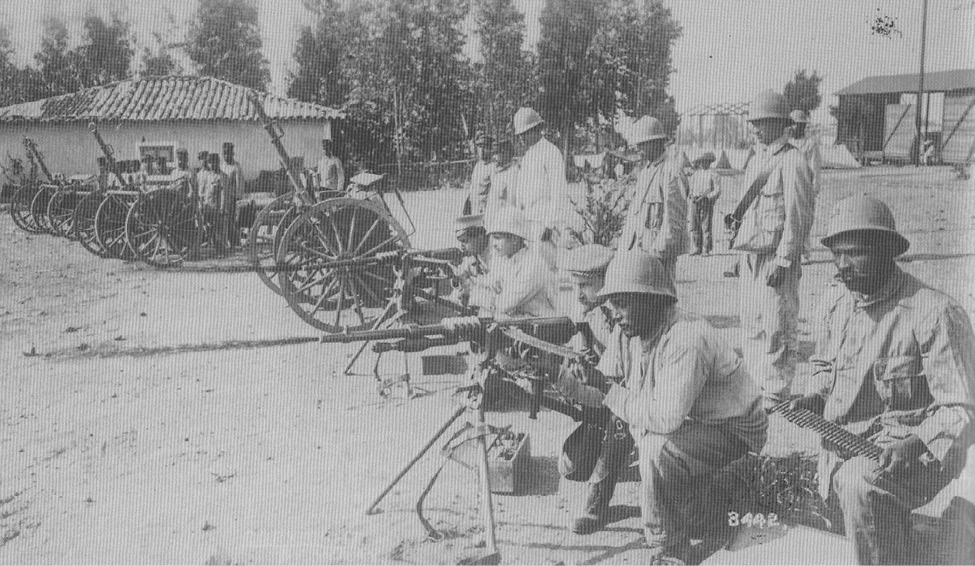

Han-Yeh-Ping Iron and Coal Company

The Han-Yeh-Ping Iron and Coal Company was located in the city of Daye (Ta-yeh), in Hubei province, in east-central China, and in two nearby centers, taking its name from Hankoy, Ta-yeh (the Wade-Giles rendering of Daye), and Pingxiang (then Pinghsiang). Situated on the south bank of the Yangzi River and about fifty-five miles (ninety kilometers) southeast of Wuhan, the provincial capital, there was a plentiful supply locally of iron, copper, and coal at Daye. As a result, there had been a government smelter there since at least the eighth century, during the Tang dynasty. In 1974 archaeologists excavated the site of a mine and copper smelter that might be even older, possibly dating back as far as the Zhou dynasty (1122–255 BCE) and the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE). The production of iron and copper during the Ten Kingdoms period and the Nan (Southern) Tang period that followed led to the settlement becoming known colloquially as the “Great Smelter.”

Following the Self-Strengthening Movement of Li Hongzhang, which operated in China from 1861 until 1895, during which government sponsorship of industries was established in China that were run by Chinese, the decision was taken to expand the iron and copper production at Daye. A factory was built at Hankou to help in the production of steel rails, which would be needed for the railroad that was being planned to link Beijing and Hankou. Iron ore from the mines at Daye was taken to Hankou for smelting.

The work on the plant at Daye was started in 1890 by the Viceroy Chang Chihtung, and the work there lasted for three years. During that time two blast furnaces were installed, each capable of an output of fifty tons per day, and there were also twenty puddling furnaces each with two steam hammers, two five-ton Bessemer converters, a twelve-ton Siemens-Martin furnace, a rail mill, a bar mill, a plate mill, and also a firebrick factory together with a mechanical workshop.

This business was initially run by the government, but it lacked the right machinery and faced considerable management and government intransigence, with long delays in decision making. They also had a problem sourcing coke for the blast furnaces. As a result, the company floundered, and in 1895 the Chinese government decided to sell it to local capitalists and investors, and Sheng Kung-pao, the then head of the China Merchants’ Steam Navigation Company, took over as the leading shareholder. Sheng Kung-pao immediately sought to purchase a coal mine, and initially he considered the one at Magan Shan but rejected it as the coal had too much sulfur in it. He then turned his attention to the Pingxiang coalfield, which had just been discovered.

To help structure the new works properly, V. K. Lee, the director of the Hanyang Works, went to the United States and Britain to study how iron and steel works operated there. He took with him Thomas Bunt, the president of the Shanghai Society of Engineers, as his technical adviser, and also Gustav Leinung, who was the chief engineer of the colliery at Pingxiang. On their return they decided that major changes would need to be made and that the plant would have to be enlarged.

In 1908, to help integrate the various operations in the region, the Hanyang Ironworks at Hankou, the iron ore mines at Daye, and the coal mines at nearby Pingxiang in Jiangxi province were all merged together into the Han-Yeh-Ping Iron and Coal Company, the name incorporating the location of the three arms of the business.

However, the business did not fare much better. The upheavals in China surrounding the Chinese Revolution of 1911 to 1912—which started in nearby Hankou—led to the company being sold in 1913 to its Japanese creditors. The Japanese planned to expand it themselves, but because of World War I, they were unable to source the machinery from Europe or from North America. This presented them with serious problems, but they kept on some of the old management, with Sun Pao-chi as the chairman and Li Ching Fong as the vice chairman. V. K. Lee remained with the company as general superintendent, and as a result much of the work there went into abeyance. In 1922 it had capital stock of $50 million.

Gradually the Japanese started to take over mines elsewhere in China, and their steel plants and mines in Manchuria started to undercut the prices of competitors in China. As a result, industry at Daye and Hankou started to decline, although the Japanese did start production there again during the period from 1939 until 1945, when they were anxious for pig iron for their war effort. After the communist victory in the Chinese Civil War, the new government of the People’s Republic of China enlarged the facilities at Wuhan, and these became major producers of iron and steel in 1957, taking over from the production at Daye.

See also: Capitalism; Factory System; Great Leap Forward; Imperialism.

—Justin Corfield

Further Reading

Cheng, Ming-ju. The Influence of Communications, Internal and External, upon the Economic Future of China. London: G. Routledge & Sons Ltd., 1930.

Feldwick, W., and W. H. Morton Cameron. Present Day Impressions of the Far East and Prominent and Progressive Chinese at Home and Abroad. London: The Globe Encyclopedia Company, 1917.

High, Stanley. China’s Place in the Sun. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1922.

Remer, C. F. Readings in Economics for China, Selected Materials with Explanatory Introductions. New York: Garland Publishing, 1980.

Hardie, James Keir (1856–1915)

A British labor leader and politician, he organized the Independent Labour Party in 1893, and in 1906 he became the first leader of the Labour Party in Parliament.

Keir Hardie was born in Scotland and went to work in the mines in 1866 at the age of ten. As he grew older he became involved in the labor movement; he led strikes and helped form unions. Eventually (1886), he became secretary of the Scottish Miners Federation and chairman of the Scottish Labour Party (1889). He also founded and edited a newspaper, The Labour Leader, in 1889.

Meanwhile, in Great Britain, a new phase of socialist thought had emerged. It went by the name of guild socialism, and it was originated by members of the Fabian Society, founded in London in 1883 to 1884. Fabians believed in evolutionary socialism rather than revolution, and they used public meetings and lectures, research, and publications to educate the public. Important early members included George Bernard Shaw and Sydney and Beatrice Webb.

Influenced by the Fabian ideology, Hardie went into politics and was elected to Parliament in 1892 as an independent labor candidate. The next year, Hardie and his followers founded the Independent Labour Party, through which they hoped to bring the socialist message to the people in a way they could understand. The aim of the Independent Labour Party was the collective ownership and control of the means of production, to be achieved through parliamentary action, social reform, the pressure of labor, and democracy in local and central government. Its platform was very sympathetic toward unions, and in its active work among unions its speakers usually avoided mention of revolution, class warfare, and Marxist concepts in general. Their approach was to emphasize ethical, nonconformist, and democratic points of view, which appealed to British workingmen.

J. Ramsey MacDonald soon joined the Independent Labour Party, and during the remainder of the 1890s the party devoted its chief efforts to winning the trade unions for independent political action. They had some success, and in 1899 the Trades Union Congress passed a resolution calling upon all working-class organizations to send delegates to a meeting where ways and means would be devised to secure more representatives of labor in Parliament. This resolution laid the foundation for the creation of the British Labour Party.

Pursuant to this resolution, a committee was formed consisting of four members: a liberal, a radical and Fabian, a social democrat, and a socialist. Two members were also selected from the Independent Labour Party, the Social Democratic Federation, and the Fabian Society. They were: J. Ramsay MacDonald, Harvey Quelch, H. R. Taylor, George Bernard Shaw, E. R. Pease, and Hardie.

The committee decided to call a conference to decide what to do next, and this conference met in London in February 1900 with 120 delegates present, representing over five hundred thousand workers belonging to trade unions and socialist organizations. The conference appointed a Labour Representation Committee of seven trade unionists, two members of the Independent Labour Party, two of the Fabian Society, and two of the Social Democratic Federation. The committee set to work at once to enlist the support of trade unionists, and in September 1900 they placed fifteen candidates in the field for the general election. Two of these candidates, Hardie and one other, were successful.

Interest in the work of the committee then increased, largely due to the Taff Vale decision that allowed the courts to force unions to pay for damages caused by strikers during labor disputes. Subsequently, two large fines were levied upon the Railway Workers Union and the South Wales Miners, which further excited the unrest of the ranks of labor who feared that union treasuries could be wiped out if such a precedent continued to be followed.

The next general election came in 1905, and the Labor Representation Committee placed fifty candidates in the field. Of these, twenty-five were elected. At that time the Miner’s Federation was the only large union not affiliated with the Committee. When it came in a few years later, labor forces in Parliament increased to forty. By that time, the Committee had come to be known as the British Labour Party.

Hardie’s last major effort was to join with those socialists who undertook a failed attempt to persuade their colleagues in the belligerent nations to oppose the war that broke out in the summer of 1914. He died in 1915.

James Keir Hardie is still remembered as a founding member of the British Labour Party, which remains a vital part of the British political system today (2008). Twelve years after its founding, in 1918, it became a socialist party with a democratic constitution, and by 1922 it had supplanted the Liberal Party as the official opposition party (the Conservative Party was in power). In 1924 J. Ramsay MacDonald formed the first Labour government with Liberal support. The party was out of power from 1935 to 1945 when a spectacular recovery brought in Clement Attlee’s government, which ruled until 1951. Between 1945 and 1951, Labour introduced a system of social welfare that included a national health service and extensive nationalization of industry. Labour regained power under Harold Wilson (1964–1970) and again in 1974 to 1979, but it foundered due to economic problems and declining relations with its trade union allies. In 1983, Michael Foot, a left-wing socialist, proposed such a radical program that Labour suffered a massive defeat. Foot was then replaced as party leader by Neil Kinnock, who sought to move the party back to the center. He succeeded, but it was not until 1997 that Tony Blair and his “New Labour” agenda brought Labor back to power.

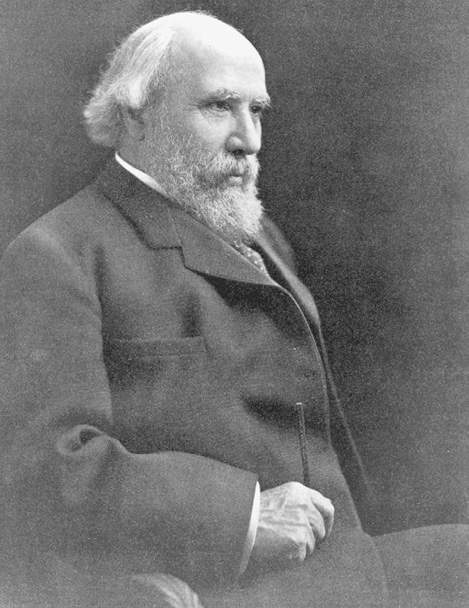

Keir Hardie

See also: General Strike of 1926; Boer War, 1899–1902; Capitalism; Collective Bargaining; Marx, Karl; Toynbee, Arnold; Trades Union Congress; Women’s Industrial Council (Britain).

—Kenneth E. Hendrickson Jr.

Further Reading

Brand, C. F. British Labour’s Rise to Power. London: H. Milford, Oxford University Press, 1941.

Cole, G. D. H. Economic Planning. New York: Knopf, 1935.

Hardie, James Keir. From Serfdom to Socialism. London: G. Allen, 1907.

Laidler, Harry W. British Cooperative Movement. New York: Co-operative League of America, 1917.

Lee, H. W., and Edward Archibald. Social Democracy in Britain: Fifty Years of the Socialist Movement. London: Social-Democratic Federation, 1938.

MacDonald, J. Ramsay. Socialism, Critical and Constructive. Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merrill, 1924.

McHenry, D. E. The Labour Party in Transition, 1931–1938. London: G. Routledge & Sons, 1938.

Shaw, George Bernard. The Socialism of Shaw. New York: Vanguard Press, 1927.

Webb, Sydney, and Beatrice Webb. The Constitution of a Socialist Commonwealth of Great Britain. New York: Longmans, 1920.

James Hargreaves is one of the most prominent names of the Industrial Revolution in Britain. He is credited with the invention of the spinning jenny, one of the first textile machines that greatly speeded the production of cotton cloth by simultaneously spinning eight threads. Little is known of Hargreaves as a person. He was born in Oswaldtwistle, England, in 1720. He received no formal education and was never taught how to read or write. He worked first as a carpenter and then as a handloom weaver near Blackburn; he had a strong interest in engineering. In the eighteenth century, the Lancashire textile workers enjoyed a degree of independence and control of their time, and the more intelligent among them sought to increase their freedom by improving their simple machinery. Hargreaves contributed to this progress by introducing improved methods of carding cotton by hand. Carding is the process of disentangling the fibers in the mass of raw cotton and laying them side by side in a filmy roll. Around 1762 Robert Peel (1750–1830), cotton manufacturer and pioneer of calico printing, sought his assistance in constructing a carding engine with cylinders that may have originated with Daniel Bourn, but this was not successful. In 1764, inspired by seeing a spinning wheel that continued to revolve after it had been knocked over accidentally, Hargreaves invented his spinning jenny.

In fact, at the time Hargreaves invented his jenny, the demand for yarn was beginning to outstrip the supply for at least two reasons. Since the 1750s, John Kay’s flying shuttle had doubled the weavers’ output and made them dependent on several spinners. Moreover, there was a considerable increase in British exports after 1760. The first jennies had horizontal wheels and could spin eight threads at once. To spin on this machine required a great deal of skill. A length of roving was passed through the clamp or clove. The left hand was used to close this and draw the roving away from the spindles, which were rotated by the spinner turning the horizontal wheel with the right hand. The spindles twisted the fibers as they were being drawn out. At the end of the draw, the spindles continued to be rotated until sufficient twist had been put into the fibers to make the finished yarn. A piecer was needed to rejoin the yarns when they broke. The thread that the machine produced was coarse and lacked strength, making it suitable only for the filling of weft, the threads woven across the warp.

The early history of the jenny is obscure. At first Hargreaves’s jenny was worked only by his family, but then he sold two or three of them, possibly to Robert Peel, who took a close interest in its construction. Hargreaves did not apply for a patent for his spinning machine until 1770, and therefore others copied his ideas without paying him any money. Hargreaves encountered other difficulties. His first spinning jenny was dismantled in 1767 by spinners fearing the possibility of cheaper competition; two years later more of his machines were destroyed. In 1776, the West Country experienced widespread popular sabotage of almost every form of machinery associated with the woolen industry. Three years later, a mob around Blackburn demolished every carding engine and all the jennies that used more than twenty-four spindles, as well as other machines using water or horse power. The local oppositions and labor riots in which Hargreaves’s house was gutted forced him to flee to Nottingham, which offered a favorable environment for innovation. The introduction of the jenny in the late 1760s occurred when wages were low and food was scarce, so workers attacked the labor-saving device. In more stable times, the jenny might have been accepted.

In Nottingham, Hargreaves entered into partnership with Thomas James and established a cotton mill in Hockley. It is not obvious why the jenny, which was worked by manual power, should have been housed in a factory. James almost certainly wanted to keep Hargreaves’s invention a secret as long as possible. In 1770 he followed the example of Richard Arkwright and sought to patent his machine, bringing a legal action for infringement against some Lancashire manufacturers, who offered £3,000 in settlement. Hargreaves held out for £4,000, but he was unable to enforce his patent because he had sold jennies before leaving Lancashire. Arkwright’s “water twist” was more suitable for the Nottingham hosiery industry trade than jenny yarn, and in 1777 Hargreaves replaced his own machines with Arkwright’s. When he died on April 22, 1778, he is said to have left property valued at £7,000. His widow received £400 for her share in the business. Once the jenny had been made public, it was quickly improved by other inventors, and the number of spindles per machine increased. In 1784, there were reputed to be twenty thousand jennies of eighty spindles each at work in Great Britain. The jenny greatly eased the shortage of cotton weft for weavers. Though the Hargreaves jenny was restricted by its design to a small number of spindles, it nevertheless enabled the cotton industry to begin a great, new advance that become one of the major sectors of the Industrial Revolution.

See also: Factory System; France; Jacquard, Joseph Marie; Luddites and Ned Lud; Spinning Mule; Textile Industry.

—François Jarrige

Further Reading

Horn, Jeff. The Industrial Revolution. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2007.

Timmins, Geoffrey. Made in Lancashire: A History of Regional Industrialization. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1998.

Weightman, Gavin. The Industrial Revolutionaries: The Creation of the Modern World (1776–1914). London: Atlantic, 2007.

Harrison, Frederic (1831–1923)

A British jurist and historian, and leading thinker of Positivism, Frederic Harrison was born on October 18, 1831, in London. His family was originally from Leicestershire, where they had been yeoman farmers for many generations. His father was Frederick [sic] Harrison, a prosperous merchant, and his mother was Jane (née Brice), originally from Belfast, Ireland. Frederic Harrison was educated at King’s College School, London, from 1842 until 1849, and after a brilliant academic career there, he won a scholarship to Wadham College, Oxford University. Harrison graduated from Oxford with a second class in the first examination held for classical honor moderations, and he gained a first class in literature and humanities with a fourth class in law and history. He was then called to the bar by Lincoln’s Inn in 1858, working as a barrister for fifteen years, most of the time spent fairly aimlessly. He married Ethel Berta Harrison in 1870, and they had four sons: Bernard O., Austin F., Godfrey Denis, and Christopher René. As boys, one of their tutors was George Gissing, the novelist, who became a family friend; the two younger sons went to Clifton College. By 1880 they were living at 38 Westbourne Terrace, Paddington, with a housemaid, a lady’s maid, a cook, a nurse, an under housemaid, and a sixteen-year-old footman.

As a barrister, Harrison initially concentrated on equity cases. However, he wanted to become an academic, and he wrote on several historical topics. Two of his articles in the journal Westminster Review were very well received. One, about Italy, was read by the Italian politician Count Cavour, who wrote to Harrison to commend him on the thoughts. The other was sharply critical of a book that had just been published. Some years later, Harrison worked with Lord Westbury on the codification of the law. Particularly interested in the role of the working class, he was a member of the Trades Union Commission of 1867 to 1869 and was secretary to the Commission for the Digest of the Law in 1869 to 1870. From 1877 until 1889 he was professor of Jurisprudence and International Law under the Council of Legal Education, and in 1877 he was in France as a special correspondent for The Times during the constitutional crisis that led to the fall of Marshal MacMahon, the first president of the French Third Republic.

Becoming increasingly radical in his politics, Harrison contested the parliamentary seat for the University of London in 1886, and he was defeated by Sir John Lubbock. Three years later he was elected as an alderman of the London County Council, becoming acknowledged as a Progressive in municipal matters.

Essentially, Positivism for Harrison encapsulated the use of strict scientific method as the basis for theories, tracing its origins to the early nineteenth-century philosopher Auguste Comte. Harrison soon became a follower of the positive philosophy that was being promoted by Richard Congreve. However, it was not long before he was in conflict with Congreve himself, and Harrison led the Positivists, who split from the mainstream movement and in 1881 founded Newton Hall, Fetter Lane, London, where supporters of Harrison started meeting on a regular basis. Harrison became president of the English Positivist Committee in 1880, holding that position until 1905. The system of strong social ethics made Positivism popular as a philosophical concept, but many of those interested in it would not go as far as viewing it as a full-fledged religion, which some of its ardent advocates felt that it was.

In 1888 he completed a biography of Cromwell, and in 1892 he was the editor of the Positivist New Calendar of Great Men. His works, The Choice of Books (1886) and Early Victorian Literature (1896) were both well received, as was his biography of the Dutch ruler William the Silent that followed in 1897. In 1900 he wrote Byzantine History in the Early Middle Ages, followed by two more biographies: Ruskin (1902) and Chatham (1905). As was the custom of the period, he also wrote a “romantic monograph,” Theophano (1904), followed by a tragedy in verse, Nicephorus (1906). His last books included Autobiographic Memoirs (1911), The Positive Evolution of Religion (1912), The German Peril (1915), On Society (1918), Jurisprudence and Conflict of Nations (1919), Obiter Scripta (1919), and Novissima Verba (1920). He was also the Rede lecturer at Cambridge University in 1900, the Washington lecturer at the University of Chicago in 1901, and the Herbert Spencer lecturer at Oxford University in 1905. He was also vice president of the Royal Historical Society, and he received honorary degrees from the universities of Oxford, Cambridge, and Aberdeen. In 1899 Wadham College, Oxford, made him an honorary fellow.

In May 1915, Frederic Harrison’s youngest son, Christopher René Harrison, died of wounds on the Western Front. He had trained as an architect, practicing in England and then in Argentina, before returning to England to enlist as lieutenant in the Leicestershire Regiment. Frederic Harrison had moved to the city of Bath, in the west of England, in 1912, and he became a local celebrity, conferred with the honorary freedom of the city in November 1921. He died on January 14, 1923, survived by his widow and his other three sons.

Frederic Harrison

See also: Marxism; Socialism.

—Justin Corfield

Further Reading

Harrison, Austin. Frederic Harrison: Thoughts and Memories. London: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1927.

Sullivan, Harry R. Frederic Harrison. Boston, MA: Twayne, 1983.

Vogeler, Martha S. Frederic Harrison: The Vocations of a Positivist. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984.

These experiments were detailed by a group of experts who studied the Hawthorne Works located on the outskirts of Chicago. A manufacturing plant of the Western Electric Company, the Hawthorne Works had been established in Cicero, Illinois, in 1905. The studies that were carried out there from 1924 until 1932 were done to see how it was possible to make workers more productive. This was especially in terms of whether they became increasingly productive in response to changes in a number of variables. The overall aim was to see how large companies could increase productivity easily.

The work involved industrial and occupational psychologists and also people studying organizational behavior under instructions from Elton Mayo and others. Initially they concentrated on the positions of two women who worked on a conveyor belt, later expanding their study to include four others. The suggestions to increase productivity included changes in pay. This did not include an increase in pay rates but with the pay for the group based on their overall production, rather than on individual production rates.

Another issue involved the provision of work breaks. When the women were given six five-minute breaks, the overall output was reduced as the women had to get back into the routine of work after each break in their working cycle. It was found that two five-minute breaks worked better than two ten-minute breaks. It was also found that if food was available or provided during the break, there was an increase in productivity.

The next issue was over the overall length of the working day. The study was able to show that when the working day was reduced by thirty minutes, overall production actually increased. However, when it was shortened more than thirty minutes, although the output per hour increased, the overall output decreased. Thus they recommended that the hours be cut to an eight-hour day, as any longer was counterproductive.

Other factors studied involved the effects of the lighting conditions, the organizational structure, the degree to which they were supervised and consulted, and other general working conditions. Essentially, it did show that the more care taken to individual employees, the better their performance, and that ill treatment of employees was counterproductive from an economic, as well as a moral, point of view.

The overall conclusions that Mayo drew from the studies covered three basic areas. The first was that the aptitude of individuals when measured by industrial psychologists were not able to predict accurately performance in the workplace. The results that the industrial psychologists were able to calculate was essentially the potential of the employee, whereas their actual productivity was dictated by many other factors.

The second conclusion was that the major effect on productivity was the informal organizational atmosphere within the factory. Previous studies of the workforce showed that workers were either dealt with as a collective mass or as isolated individuals, both operating within a formal chart that highlighted the hierarchical positions and responsibilities that formed the management structure of the company in question. The work in Hawthorne demonstrated that the individual behavior of the supervisors and foremen and how they managed to develop a rapport with the workers was the most important factor into whether employees did carry out their work, and how efficiently they went about it. A bad supervisor, or one who did not treat employees individually, led to a major fall in the output of all the workers under them regardless of the threats that they were able to use.

The Hawthorne researchers believed that the major factor that influenced productivity was the norms of the work group, with most people regarding that workers felt that they came to accept that there would be a norm for “a fair day’s work.” As a result, people working in production tended to structure their work at what they felt were the normal levels expected. As a result, even if workers were able to produce more and even if they were financially rewarded for more, the level of output did not increase for any sustained period. Although this had long been suspected, the researchers at Hawthorne were the first to be able to tabulate it systematically.

The overall conclusion of the Hawthorne researchers was that the workplace is a microcosm of a social system. Made up from a number of independent parts, human behavior tends to be able to be altered for short periods of time by some factors but will often return to a normal level that is, in turn, dictated by how the workers are treated and respected.

See also: Industrial and Organization Psychology.

—Justin Corfield

Further Reading

Adair, John G. “The Hawthorne Effect: A Reconsideration of the Methodological Artifact.” Journal of Applied Psychology 69, no. 2 (1984): 334–45.

Gillespie, Richard. Manufacturing Knowledge: A History of the Hawthorne Experiments. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Jones, Stephen R. G. “Was There a Hawthorne Effect?” American Journal of Sociology 98, no. 3 (November 1992): 451–68.

Landsberger, Henry A. Hawthorne Revisited. Ithaca: New York State School of Industrial and Labor Relations, 1968.

Mayo, Elton. Hawthorne and the Western Electric Company: The Social Problems of an Industrial Civilization. London: Routledge, 1949.

Roethlisberger, Fritz J., and W. J. Dickson. Management and the Worker. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1939.

Trahair, Richard C. S. The Humanist Temper: The Life and Work of Elton Mayo. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2005.

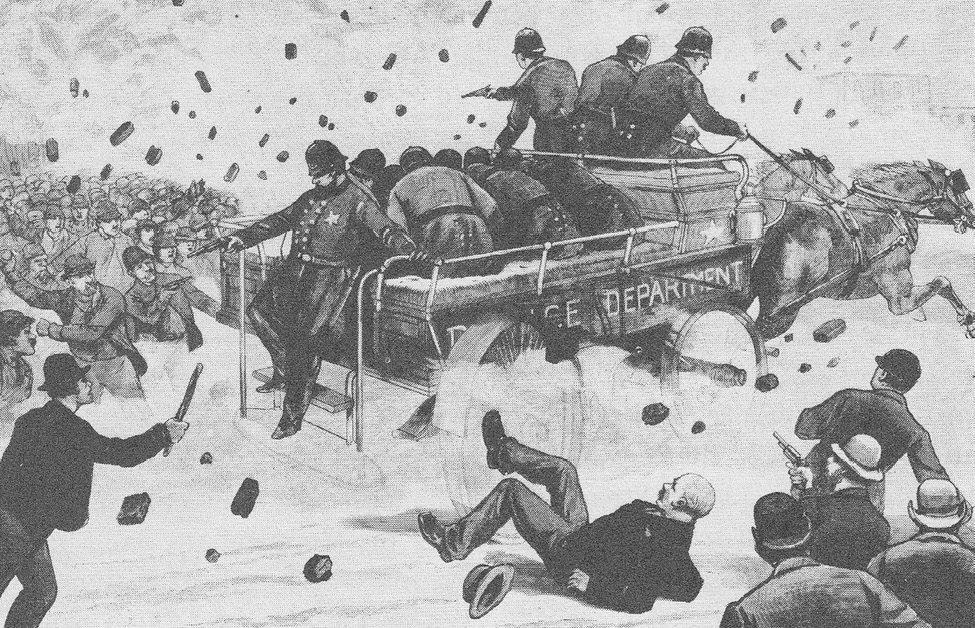

On May 4, 1886, a riot occurred near Haymarket Square in Chicago between workers and the city’s police. Someone threw a bomb, killing seven policemen and an indeterminate number of civilians in the blast and the ensuing shooting. The incident climaxed the class tension that had been building between labor and business in the city. Conflict surged around demands for an eight-hour day—the main goal of the American labor movement in the late nineteenth century—and underscored ethnic tensions since many of the laborers were immigrants of German and East-European origin. The ensuing outrage over the riot and the death of the policemen effectively killed the burgeoning anarchist/socialist movement and set back union and labor efforts across the United States.

The meeting in the Haymarket in the evening of May 4 was in response to a confrontation between police and striking workers the evening before at McCormick Reaper Works, during which the police had opened fire. The Haymarket meeting was reportedly peaceable. However, as the last speaker was winding down around 10:20 p.m., a column of armed policemen approached the group of several hundred listeners. The police ordered the meeting to disperse. Eyewitness accounts differ as to what exactly happened next, but a dynamite bomb landed at the front line of the police. After the bomb detonated, gunfire erupted mainly from the police, who in their confusion shot even at each other. Chaos ensued as people fled for their lives. The next day found a city terrified of a violent anarchist conspiracy. Chicago became home to the nation’s first major Red Scare as newspapers demanded vengeance for the policemen’s deaths. A flurry of arrests of prominent anarchist and socialist speakers and leaders followed. For the next several months, city authorities squelched civil liberties such as free speech and freedom of the press in the name of public safety. Union activity came to a halt as striking workers found themselves blamed in part for the bombing. The eight-hour movement declined, and many workers returned to their jobs defeated.

Although no one was certain who threw the bomb, eight men—Samuel Fielden, George Engel, Michael Schwab, Adolph Fischer, Louis Lingg, Oscar Neebe, August Spies, and Albert Parsons—were arrested and tried for murder. These men had all endorsed violence at one time or another. The prosecution, headed by Julius Grinnell, argued that they were part of an anarchist conspiracy to commit murder and were as guilty as the actual bomb thrower. Citizens throughout the city and the nation condemned the defendants even before they went on trial and demanded the death penalty. The jury was stacked with businessmen, who all admitted that they were biased, but Judge Joseph Gary insisted that the trial was fair. Evidence neither specifically linked any of the defendants to the throwing of the bomb nor to any conspiracy, but all eight were nevertheless found guilty on August 20, 1886. Seven were sentenced to death, and Neebe was sentenced to fifteen years in prison. Six months after the verdict, the defense lost its appeal at the Illinois State Supreme Court. Anarchist and radical labor politics in Chicago and Illinois collapsed.

In October 1887, the U.S. Supreme Court heard the appeal, with defense lawyers arguing that the prosecution had violated the defendants’ constitutional rights. However, in early November, the Supreme Court ruled that it did not have jurisdiction over this case, since constitutional violations were only relevant in federal cases. The final option to save the defendants’ lives was for Illinois governor Richard James Oglesby to commute their sentence. Pleas and petitions from all over the world were delivered to the Oglesby’s office. On November 10, Lingg committed suicide in his prison cell by exploding a dynamite cap in his mouth. That afternoon, Governor Oglesby commuted the sentences of Fielden and Schwab to life imprisonment. He upheld the death sentences of the other four, and on November 11, 1887, Spies, Fischer, Engel, and Parsons were hanged. They became martyrs to countless thousands of workers throughout the world. After a massive public funeral, the men were buried on November 13. Their deaths profoundly affected many, including Emma Goldman and Mother Jones, both of whom became labor activists themselves. In addition, the Haymarket incident eventually fused with the celebration of May Day as International Workers’ Day in 1890, as the eight-hour workday movement regained popularity. In June 1893, a monument was placed on the graves of the martyrs, and thousands traveled from the World’s Fair in Chicago to see it. That same month, Illinois’s new governor, John Peter Altgeld, pardoned Neebe, Fielden, and Schwab.

However, labor issues in Chicago were not easily resolved. The Haymarket Affair remained prominent in the popular memory, revived during the Red Scares after the assassination of President William McKinley in 1901 and as the United States entered World War I in 1919 to 1920. In addition, activists invoked the Haymarket memory during the crisis surrounding the trial and execution of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti in 1927 and during violent labor struggles in Chicago in the 1930s. In 1969 and 1970, the militant Weathermen faction of the Students for a Democratic Society attacked a monument to the police officers killed during the riot. City officials moved it to an area closed to the public. In 2004, the city dedicated a new monument that better reflected both sides of the issues that clashed on that May evening in 1886.

An attack on a police wagon near McCormick’s Reaper Works.

See also: Communism; Socialism.

—Sarah McHone-Chase

Further Reading

Avrich, Paul. The Haymarket Tragedy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1984.

David, Henry. The History of the Haymarket Affair: A Study in the American Social-Revolutionary and Labor Movements. New York: Farrar and Rinehart, 1936.

Green, James. Death in the Haymarket: A Story of Chicago, the First Labor Movement and the Bombing That Divided Gilded Age America. New York: Pantheon, 2006.

Roediger, Dave, and Franklin Rosemont, eds. Haymarket Scrapbook. Chicago: Kerr, 1986.

Werstein, Irving. Strangled Voices: The Story of the Haymarket Affair. New York: Macmillan, 1970.

Haywood, William Dudley “Big Bill” (1869–1928)

William D. “Big Bill” Haywood was one of the most radical and successful American labor leaders and enemies of capitalism in the early twentieth century. Physically imposing with a thunderous voice and total disrespect for the law, he mobilized unionists, intimidated company bosses, and often found himself facing prosecution. From 1908 to 1918 he led the Industrial Workers of the World, one of the nation’s most militant unions.

Haywood was born in Salt Lake City, Utah, on February 4, 1869, and began work as a miner at the age of nine. He was deeply impressed by the Haymarket Affair followed by the trials and executions of 1886 and 1887, and he said later that these events inspired him to a life of radicalism. The Pullman strike of 1894 further strengthened his interest in the labor movement, and in 1896, while he was working in a silver mine in Idaho, Haywood listened to a speech by Ed Boyce, president of the Western Federation of Miners (WFM). He immediately joined the union, and by 1900 he had risen to a position on the executive board. In 1901, he joined the newly formed Socialist Party of America.

When Boyce retired in 1902, he recommended that Haywood and Charles Moyer assume joint leadership of the union. This proved to be a difficult arrangement because Moyer was cautious by nature, favoring negotiations over strikes and violence. Haywood, on the other hand, had no compunctions and was a master at rallying working-class audiences. The campaign for an eight-hour day became one of his principal causes, and he was willing to do anything in order to force mine owners to an agreement.

Beginning in 1902, the WFM, the mine owners, and the Colorado government became locked in a long struggle known as the Colorado Labor Wars. This violent series of events took thirty-three lives. In one single incident at the Independence, Colorado, train depot on June 4, 1904, thirteen nonunion workers were killed by an explosion as they waited for a train. Haywood was the main suspect, and a virtual open season on unionists began. When former Colorado governor Frank F. Steunenberg was assassinated in 1906, Haywood was arrested and charged with the murder. While awaiting trial in the Boise, Idaho, jail, he busied himself reading. Among his favorite selections were such diverse works as Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle and Thomas Carlyle’s The French Revolution. From his jail cell he ran for governor of Colorado on the Socialist ticket, designed new WFM posters, and took a correspondence course in law. When the jury found him not guilty in May 1906, Haywood hugged his supporters and shook hands with each juror.

Meanwhile, Haywood had played a major role in the founding of the Industrial Workers of the World. At a convention in Chicago in 1905, Haywood, along with Eugene V. Debs, leader of the Socialist Party, and Daniel De Leon, founder of the radical Socialist Labor Party, and some of the more radically inclined members of the Western Federation of Miners, dominated the proceedings and brought forth the IWW declaring that the universal economic evils affecting the working class could be eradicated only by a universal working-class movement. They envisioned their creation as “one great industrial union” embracing all industries and founded on the premise of class struggle recognizing the irrepressible conflict between the capitalist class and the working class. They advocated direct action as a means to victory, by which they meant the use of such tactics as the general strike, boycott, and sabotage.

In 1908, after Moyer ousted Haywood from his executive position with the WFM, he turned his full attention to the Industrial Workers of the World, and by 1915 he had become the leader of that organization. The IWW appealed to the great class of unorganized, unskilled workers, especially certain groups of Eastern factory workers, such as those in the textile mills of the East and the migratory workers of the West. From 1909 to 1917 it was a very aggressive organization and led a number of major strikes. Strikes in Lawrence, Massachusetts (1912), and Paterson, New Jersey (1912), attracted national attention. In Lawrence, when strikers sent their children, ill clad and hungry, out into the streets, the “Wobblies,” as the IWW people were known, found them places to stay. During the Paterson strike they rented New York City’s Madison Square Garden for a massive labor pageant. Haywood and his colleagues believed that local strikes such as these would bring about capitalist repression that in turn would lead to a general strike and eventually a workers’ commonwealth.

The methods and the revolutionary language of the IWW aroused the hostility of the public and inclined it to condone the extralegal methods used by communities to rid themselves of this group. Then, the opposition of the IWW to the war brought them into direct conflict with the government, which further curtailed their operations. In 1918, during World War I, Haywood was convicted of violating the federal espionage and sedition acts by calling a strike in wartime. After serving a year in prison, he jumped bail while awaiting an appeal and fled to Moscow, where he became a trusted adviser to the new Bolshevik regime. He died in Moscow on May 18, 1928, and his body was cremated. Half his ashes were entombed in the Kremlin near his friend John Reed, and the other half went to Chicago to be buried near the monument to the Haymarket anarchists who had inspired his life of radicalism.

Soon after the end of World War I the Socialist Party went into swift decline, as did the IWW. In fact, the labor movement as a whole, including such organizations as the American Federation of Labor, was severely weakened during the conservative era of the 1920s and did not recover and begin to flourish again until the New Deal period of the 1930s.

See also: Factory System; Lenin, Vladimir Ilyich; Capitalism; Child Labor; Corporation and Incorporation; Debs, Eugene “Gene” V.; Depression of 1893; Lawrence Textile Strike; Lowell Mills; Paterson Silk Strike of 1913; Pullman, George Mortimer; Sweatshop.

—Kenneth E. Hendrickson Jr.

Brissenden, Paul F. The IWW: A Study in American Syndicalism. New York: Columbia University Press, 1920.

Carlson, Peter. Roughneck: The Life and Times of Big Bill Haywood. New York: W. W. Norton, 1983.