…

Flopping to the Top Dick Fosbury used his signature Flop, clearing the bar upside down and backward, at the 1968 Mexico City Games. The innovative move became the preferred technique of high jumpers.

THE OFFICIAL OLYMPIC MOTTO,CITIUS-ALTIUS-FORTIUS, IS LATIN for “faster-higher-stronger” and dates to 1881, when a priest named Henri Didon used it to open a school sports event in Paris. More than a decade later, organizers adopted those three ideals for the inaugural modern Olympics in 1896. The goals continue to embody the hopes of every athlete, and if a fourth could be added, it might very well be first. Every athlete strives to be first—first on the podium, and in some cases, the first to attain the unachievable. Here are a few groundbreaking individuals who had a lasting influence on their sport and beyond.

Jim Thorpe

With his epic performance at the 1912 Games, the multifaceted star set the standard for the title of World’s Greatest Athlete.

…

The discus throw, high jump, and foot races.

JIM OF ALL TRADES: Thorpe posed on the field at the 1912 Games. He became the first Olympic decathlon champion, dominating an event.

Jim Thorpe was first a star in baseball and football, but it was his dominating showing in track and field at the 1912 Stockholm Olympics that caught the world’s attention. The 10-event decathlon and the five-event pentathlon were both relatively new competitions at the 1912 Games. The track-and-field events were designed to measure all-around athleticism, and Thorpe proved that he could do it all.

Before the pentathlon, Thorpe’s sneakers were stolen, so he pulled a replacement pair out of the garbage and competed in a pair of mismatched shoes. Despite his improvised footwear, Thorpe placed first in four events to win gold. The discipline in which he was not the top finisher—the javelin—was one that he had never competed in before 1912. Still, he had the third-longest throw.

Then came the decathlon. The U.S. trials did not hold a decathlon because it didn’t have enough entrants. The Olympics marked the first time Thorpe took part in the event. Swedish hero Hugo Wieslander was expected to dominate on his home turf, but instead Thorpe defeated him by more than 700 points; his tally of 8,413 stood as the Olympic record for another 20 years. At the closing ceremonies, King Gustav V of Sweden summed up everyone’s thoughts when he told Thorpe, “You, sir, are the greatest athlete in the world.”

But Thorpe’s Olympic triumph took an unfortunate turn. The Games had a strict amateurism rule, and a year later, it was discovered that Thorpe had accepted money to play professional baseball in the Eastern Carolina League. As a result, the Amateur Athletic Union retroactively withdrew Thorpe’s amateur status. Then the International Olympic Committee stripped Thorpe of his Olympic medals. Because so much time had passed since the Games, many supporters believed Thorpe was treated unfairly. They tried to have Thorpe’s medals and records reinstated, but the effort stalled. It wasn’t until 29 years after his death, in 1982, that his name was officially cleared.

When Thorpe, a member of the Sac and Fox Nation, died in 1953, the New York Times obituary told a story from his days as a collegiate track star for Carlisle Indian Industrial School, in Pennsylvania. It summed up Thorpe’s impressive talent. Carlisle was scheduled to compete in the town of Easton, but the welcoming committee was puzzled when only two people got off the train.

“Where’s your team?” they asked.

“This is the team,” replied Thorpe.

“Only two of you?”

“Only one,” Jim said with a smile. “This fellow’s the manager.”

GIANT AMONG MEN Thorpe, a star for the New York Giants on the baseball field, prepared for his at-bat at the Polo Grounds in New York.

THEN THERE WAS…

BRUCE JENNER

Going into the trials for the 1972 Olympics in Munich, Bruce Jenner was a little-known decathlete on the U.S. track-and-field scene. It took a come-from-behind effort at the trials, one in which he sprinted the final lap of the 1,500 meters, to make the squad.

Jenner ended up finishing 10th in Munich, but he was inspired by the regimen of Soviet Mykola Avilov, the gold medal winner. Over the next four years, Jenner spent six hours a day training, and by the time the 1976 Montreal Games arrived, he had set the decathlon world record twice. On the first day of competition in Montreal, Jenner achieved personal bests in three events. Gold seemed virtually guaranteed—the only question was whether he would set another world record. He did, with 8,618 points (later adjusted to 8,634). Jenner had earned the title of World’s Greatest Athlete and became an American hero on the track.

The sports star went on to become an icon in the entertainment industry. In 2015, Jenner came out as a transgender woman, legally changing her name to Caitlyn Jenner. She is considered a role model for the LGBT community and was given the Arthur Ashe Courage Award at the 2015 ESPYs.

VICTORY LAP Jenner easily won gold in the decathlon at the 1976 Montreal Olympics, setting a world record along the way.

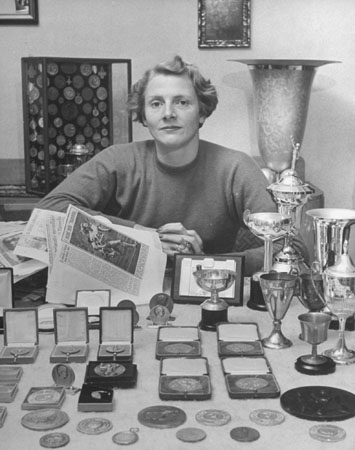

Known as the Flying Housewife, the Dutch star defied stereotypes at the 1948 Olympics and redefined what it meant to be a female athlete and mother.

…

The Dutch track star posed with her collection of medals and trophies.

The Olympic career of Dutch track-and-field star Fanny Blankers-Koen started with little fanfare. In her first Olympics, the 1936 Berlin Games, she returned home without a single medal. Two years later, at the European championships, Koen won bronzes in the 100- and 200-meter races. Not long after, she married her coach, former Olympian Jan Blankers, and gave birth to the couple’s first child, Jantje. For most women of her era, the story of an athletics career would have ended there.

But within weeks of her son’s birth, Blankers-Koen was back on the track—and soon showed she was better than ever. Between 1942 and ’44, she set six world records: in the high jump, long jump, 80-meter hurdles, 100-yard dash, and as a member of the 4×110-yard and 4×200-meter relay teams. The feats earned her the nickname the Flying Housewife. She gave birth to a second child, daughter Fanneke, six weeks before the start of the 1946 European championships, the first major athletics event since the end of World War II. There, Blankers-Koen delivered gold in the 80-meter hurdles and 4×100 relay.

Blankers-Koen was 30 years old by the time the 1948 London Olympics began. She was the oldest woman in her sport and many questioned her priorities. “One newspaperman wrote that I was too old to run, that I should stay at home and take care of my children,” she once said. “When I got to London, I pointed my finger at him and I said, ‘I show you.’ ”

At the London Games, track athletes were allowed to enter only three individual events. Though she was the world record holder in the high jump and long jump, Blankers-Koen chose not to compete in those events. She entered the 100-meter competition and took home gold. Then, after some encouragement from her husband to compete in the 80-meter hurdles, Blankers-Koen edged British rival Maureen Gardner in the finals of that event. Her next race, the 200 meters, was not nearly as close. She won the final by seven-tenths of a second, the largest margin of victory ever in an Olympic 200 final.

In her final race of the London Games, Blankers-Koen anchored the 4×100 relay team. The Dutch squad was in fourth place when she got the baton. She made up the difference and then some, clinching her fourth gold medal of the Games. She remains the only female track athlete to ever win four golds in a single Olympics.

HEAVY MEDAL: The 80-meter hurdles final at the 1948 Games was a tight race. Blankers-Koen beat her archrival, Britain’s Maureen Gardner, in a photo finish.

ALL IN THE FAMILY Four-time gold medal winner Blankers-Koen with her husband, Jan; son, Jantje; and daughter, Fanneke, while on vacation in Amsterdam.

THEN THERE WAS…

KERRI WALSH JENNINGS

Kerri Walsh Jennings has dominated the sport of volleyball, in the indoor game and on the beach. As a member of the indoor team at Stanford University, she was a four-time All-America, two-time national champion, Final Four MVP, and co-National Player of the Year. She was also a member of the 2000 U.S. Olympic team. In 2001, Walsh switched to beach volleyball, teaming with fellow Californian Misty May-Treanor to form the greatest duo ever in the sport. Between 2004 and 2008, the pair went undefeated and won two Olympic gold medals.

After the 2008 Olympics, Walsh Jennings and her husband, professional beach volleyball player Casey Jennings, started a family. By the time the 2012 Games came around, Walsh Jennings was the mother of two boys—and in peak form. She and May-Treanor won their third consecutive gold. Perhaps most impressive, Walsh Jennings achieved that feat with a secret under wraps: “When I was throwing my body around fearlessly, and going for gold for our country, I was pregnant,” she told the Today show. Eight months later, Walsh Jennings gave birth to her third child, a daughter named Scout.

Dick Fosbury

The high jumper invented a new technique that helped him win gold at the 1968 Games and forever changed the sport.

…

NEW HEIGHTS: Fosbury cleared the bar using his unique technique at the 1968 Mexico City Games, on his way to setting an Olympic record of 7 ¼ feet (2.24 meters). After the 1968 Games, Fosbury retired from competition and went on to start his own engineering company.

In his early days as a high school high jumper at Medford High School, in Oregon, Dick Fosbury was decidedly unremarkable. As a sophomore in 1963, he failed to clear five feet, a minimum requirement for many state meets. At the time, most high jumpers were using a method called the Western roll, or straddle. It involved leaping off the inner leg and clearing the bar facedown, often ending up on two hands and one leg in a landing pit made of wood chips. The gangly Fosbury was unable to master the technique, so he turned to an old-fashioned move that involved kicking the inner leg over the bar first and landing upright on two feet.

He continued to modify the move and was aided in his mission by the advent of soft foam pits that cushioned his landing. First, he finished his run-up on a slight curve. He then rotated his body at takeoff, clearing the bar headfirst and faceup. This allowed Fosbury to land on his back—an option that would have been too painful in the wood-chip days. Fosbury improved rapidly as he honed the new approach, finishing second at the Oregon state meet his senior year in high school. The Medford Mail-Tribune ran a photo of him with the caption “Fosbury Flops Over the Bar,” and the unique technique had a name: the Fosbury Flop.

When Fosbury arrived at Oregon State University in 1965, coach Berny Wagner dismissed the Flop. He described it as “a shortcut to mediocrity” and encouraged Fosbury to work on the straddle technique again. But the summer after Fosbury’s freshman year, Wagner captured the Flop on video. It was then that he realized Fosbury could clear seven feet. The Flop was the future.

Fosbury won the NCAA championship as a junior in 1968, as well as the U.S. Olympic trials. At the 1968 Mexico City Olympics, the Fosbury Flop was introduced to the world. The crowd gasped as it watched Fosbury clear 7 feet, 4¼ inches (2.24 meters) with his unorthodox move. With that jump, he won the gold medal. At the Munich Games four years later, 28 of the 40 high jump competitors used the Fosbury Flop. And nearly 50 years later, it has become the standard technique in the sport.

QUANTUM LEAP: This multiple-exposure image of Fosbury at the 1968 Olympics shows each step of the Fosbury Flop, in which he jumped headfirst and faceup.

THEN THERE WAS…

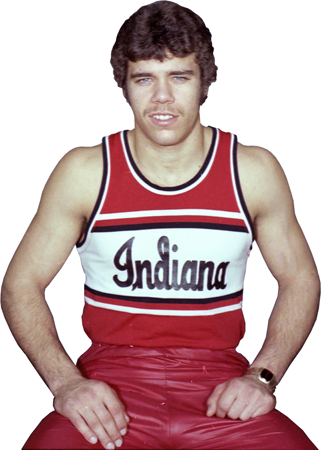

DAVE VOLZ

Fosbury wasn’t the only track-and-field athlete to create a new technique. In the 1980s, pole vaulter Dave Volz also came up with a unique approach in his event.

In pole vault, competitors avoid touching the bar so as not to dislodge it, which results in a penalty. Volz decided to take the opposite tack: He would grab the bar to steady it. Sometimes he would even remove it and then put it back on its pegs while in midair. The move became known as Volzing.

Volzing was great theater that showcased the pole vaulter’s amazing athleticism. At Indiana University, he set the American record twice during the 1982 season. He won bronze at the 1985 Universiade, a world Olympiad for college athletes. Injuries prevented him from making the Olympic team in 1984 and ’88, but Volz competed at the 1992 Barcelona Games. There, the 30-year-old finished fifth. Unlike the Fosbury Flop, Volzing did not catch on as the go-to technique in the sport. In fact, it was declared an illegal move in 1998.

Nadia Comaneci

At the 1976 Olympics, the Romanian gymnast showed the world that even at age 14, perfection was attainable.

…

RAISING THE BAR Comaneci performed one of her routines on the uneven bars at the 1976 Olympics. The Romanian gymnast scored four perfect 10s on the bars and became the first woman to receive a perfect 10 in an Olympic gymnastics event.

Before the 1976 Montreal Games, the Swiss luxury watch company Omega asked organizers how many digits the scoreboard for the gymnastics venue would need. The IOC, assuming that a perfect score of 10.00 would be impossible to achieve, suggested three.

It didn’t take long for Nadia Comaneci, a 14-year-old gymnast from Romania, to expose the faulty reasoning. On the Games’ first full day of competition, Comaneci executed a flawless routine on the uneven bars, earning a 10.00. The scoreboard, with only three spaces, had to display the historic score as 1.00.

Amazingly, Comaneci repeated the feat six more times in Montreal. She scored four 10s on the uneven bars in the team compulsory, team optionals, individual all-around, and event finals. But not to be forgotten was her performance on the balance beam, where she scored three 10s, wowing the crowd.

As Sports Illustrated’s Frank Deford wrote at the time: “The [uneven bars] demands such a spectacular burst of energy in such a short time—only 23 seconds—that it attracts the most fanfare. But it is on the beam that her work seems more representative of her unbelievable skill. She scored three of her seven 10s on the beam. Her hands speak there as much as her body. Her pace magnifies her balance. Her command and distance hush the crowd. ‘And everyone is scared on the beam,’ says Boris Bajin, the Canadian coach. ‘It is the most difficult. No matter how good they are, they are all shaking inside.’ ”

Even with a challenge from Soviet gymnast Nellie Kim, who scored three 10s, the Olympics belonged to Comaneci. She added individual gold in the beam and bars, as well as bronze in the floor exercise and silver in the team competition. Comaneci is still the youngest all-around champion in Olympic history, a mark that won’t soon be broken now that the minimum age requirement has been raised to 16.

PERFECT STORM Comaneci celebrated one of her seven flawless scores at the Montreal Games. In 2006, the International Federation of Gymnastics did away with the 10-point scale and introduced a more complicated scoring system.

THEN THERE WAS…

MARY LOU RETTON

In 1982, Mary Lou Retton was a 14-year-old with a pixie cut who dreamed of winning Olympic gold. She left her home in West Virginia and moved to Houston to train with Béla and Márta Károlyi, the world-renowned coaches who had worked with Nadia Comaneci.

Retton immediately became a star under the Károlyis, winning the American Cup and taking silver at the U.S. Nationals in 1983. The following year, she won the American Cup, Nationals, and the Olympic trials, establishing herself as a serious contender for all-around gold at the 1984 Los Angeles Games.

It wasn’t an easy road, however. During the individual all-round competition, Romanian Ecaterina Szabo opened up a lead against Retton. The floor exercise and vault events remained. To bring home gold, Retton needed to be perfect. And she was: Retton scored 10s in both events, edging Szabo by 0.05 of a point to become the first U.S. athlete to win all-around Olympic gold in gymnastics. For her achievement, she landed on the cover of a Wheaties cereal box and forever became the country’s darling.

AMERICA’S SWEETHEART: Retton, performing a floor routine at the 1984 Olympics, became the first U.S. woman to win gymnastics all-around gold. Retton also took home two silver and two bronze medals, making her the most decorated athlete at those Games.

Jonny Moseley

The skier brought style to the slopes at the 1998 and 2002 Olympics. He thrilled crowds with his showstopping moves and ushered in an era of action sports at the Games.

…

For much of the history of the Winter Games, skiing events had a certain monotony, with each athlete racing independently against a clock. Other than the differences in finish time, individual runs seemed pretty much the same. Then came freestyle skiing. With its spectacular aerial jumps and mogul courses full of tight turns and bumps, freestyling was a way for the IOC to inject a new level of excitement into skiing events. The committee introduced moguls as a demonstration sport at the 1988 Calgary Games, and then as a medal sport at the 1992 Olympics in Albertville.

The mix of speed and style kicked off a new era of Winter Games sports and athletes. And no one was more responsible for that evolution than American freestyle skier Jonny Moseley.

Moseley competed in moguls, where athletes’ scores are based on their times as well as the form and difficulty of their jumps. At the 1998 Nagano Games, Moseley’s near-perfect final run landed him a gold medal.

In 1999, Moseley participated in the third annual Winter X Games, the biggest action sports competition at the time. In the Big Air competition, in which athletes perform daredevil tricks, Moseley won silver to become the first athlete to win both Olympic and X Games medals.

At those X Games, Moseley unveiled a difficult aerial trick called the Dinner Roll, in which he flew off the ramp and rotated 720 degrees in the air, with his body parallel to the ground, before landing on his skis. Moseley wanted to perform the move at the 2002 Olympics, but judges questioned whether it violated moguls rules that said a skier cannot be inverted or bring his skis above his shoulders. Moseley lobbied the skiing federation to allow the Dinner Roll and even submitted video footage to support his position. Eventually, the officials agreed, a Moseley went to the 2002 Salt Lake City Olympics ready to perform the trick.

On the day of the men’s moguls competition, a crowd of more than 14,000 cheered in anticipation of the gravity-defying move. On the second jump of his run, Moseley unleashed the Dinner Roll and landed cleanly. After crossing the finish line, he took a left turn and sailed over a barrier into a group of frenzied fans. Because the elaborate move added time to the clock, Moseley finished fourth in the competition and was eliminated from medal contention. But he was all anyone was talking about that day. “The nice part about going for it and losing is that I did something sick,” Moseley said afterward. “And the crowd was stoked.”

ONE OF A KIND: Moseley performed acrobatic tricks in the air, helping him seal a gold medal in the men’s moguls event at the 1998 Olympics in Nagano.

BOLD MOVES: Moseley celebrated at the 2002 Games after finishing an entertaining run that included a trick in which he rotated 720 degrees in the air.

THEN THERE WAS…

SHAUN WHITE

Shaun White, who had already piled up X Games medals in skateboarding and snowboarding as a teenager, was a superstar in the sports world before he ever competed in an Olympics. But the 2006 Turin Olympics is what made everyone take note of the athlete nicknamed the Flying Tomato for his fearless tricks in the air and his long red hair.

White competed in the half-pipe in his Olympic debut, in 2006. He botched his qualifying run but came back strong to make it into the finals. With a series of high-flying flips and jumps, White blew away the competition, scoring 46.8 out of a possible 50, and took home gold.

Four years later, at the Vancouver Games, White dominated again. His score on his first run was so high that he was assured gold even before his second run. With nothing to lose, he attempted and landed a Double McTwist 1260, an incredible move that features two flips and three and a half twists. His second run landed him a score of 48.4, more than three points higher than any other Vancouver competitor.

ACTION STAR: White soared during the men’s half-pipe competition at the 2006 Olympics. Scoring 46.8 out of 50, he dominated the field to take home his first Olympic gold medal.

With her home country hosting the 2000 Sydney Games, the track star blazed a trail for Indigenous Australians and became a role model.

…

PRIDE OF A NATION Freeman proudly carried the Australian and Australian Aboriginal flags after winning the 400 meters in front of a home crowd at the Sydney Games.

Cathy Freeman, one of Australia’s greatest sprinters, not only amazed sports fans but also won the world’s admiration for exposing discrimination faced by Indigenous Australians. Freeman first made a name for herself at the 1994 Commonwealth Games, winning the 200- and 400-meter races and becoming the first Indigenous Australian to win gold. She went on to take home the silver in the 400 at the 1996 Atlanta Olympics.

The sprinter raised her profile further in 1997, when she won the world championship in the 400. In 1999, she defended her world title, while winning every 400-meter race she entered. Freeman was the pride of Australia going into the 2000 Games, which were being held in her home country, in Sydney.

Chosen to light the flame at the opening ceremonies, Freeman became the first competing athlete in Olympic history to hold that honor. Given the government’s mistreatment of Aborigines in the past, the symbolism of the choice was noted by the media. Australia was seeking to launch a new era. “She has emerged as a symbol of Australia’s edgy transformation from the white male-dominated imperial outpost that staged the 1956 Olympics to the multicultural melting pot of 2000,” Guardian newspaper columnist Matthew Engel wrote following the ceremony.

Ten days after the torch was lit, the spotlight was back on Freeman in the 400-meter final. A crowd of more than 100,000 fans cheered as the country’s great gold medal hope approached the starting blocks. Freeman was the clear favorite—her main rival, France’s Marie-José Pérec, was not competing at the Games—but the pressure was as intense as ever.

Freeman started the race conservatively, and at one point was third in the pack. But with 60 meters left, Freeman turned on the jets and cruised to the finish line. “What a legend! What a champion!” exclaimed commentator Bruce McAvaney. His broadcast partner, former Olympian Raelene Boyle, added, “What a relief.”

During her victory lap, Freeman carried both the official Australian and the Australian Aboriginal flags. “It was no big deal,” said Freeman at the time. “I was just somebody who wanted to display a flag that everybody knew about and nobody ever saw.”