ULTIMATE UNDERDOGS The U.S men’s hockey team cheered on the ice after its unlikely upset of rival U.S.S.R. on its way to winning the gold medal. The win was dubbed the top sports moment of the 20th century.

“NEVER UNDERESTIMATE THE POWER OF DREAMS AND THE INFLUENCE of the human spirit,” track-and-field great Wilma Rudolph once said. “We are all the same in this notion: The potential for greatness lives within each of us.” This sentiment rings true at each Olympics. The Games put on full display the heart of underdogs, the perseverance of unlikely heroes, and the courage of athletes in the face of difficult circumstances.

Cold War rivals faced off on the ice at the 1980 Lake Placid Olympics, with the United States pulling off one of the greatest upsets in sports history.

…

Craig’s dramatic kick save with 33 seconds left in the game gave the United States a 4–3 win, allowing the team to celebrate the upset in front of a raucous home crowd.

To describe the 1980 medal-round game between the United States and the Soviet Union ice hockey teams as a matchup of men versus boys would not be an exaggeration. The U.S.S.R. team comprised veteran stars from the Soviet League, one of the strongest professional hockey leagues in the world. The country was a four-time defending gold medalist, going 27-1-1 during that span. The American team was made up of collegiate players. The team’s average age of 20.7 years made them the youngest squad in U.S. Olympic hockey history. Going into Lake Placid, the Americans had won only one hockey gold, in 1960.

During the Lake Placid Games, tensions were high between the United States and the Soviet Union. President Jimmy Carter was attempting to slow the arms race between the superpowers by initiating a second round of Strategic Arms Limitation Talks in 1979, but those efforts were undermined by the Iranian and Nicaraguan revolutions, both of which ousted U.S.-friendly regimes in favor of Soviet-supported ones. Finally, the Sovietinvasion of Afghanistan in December 1979 had led Carter to threaten a boycott of the 1980 Games in Moscow.

Against this Cold War backdrop, the rivals were set to meet on the Olympic ice in Lake Placid. The squad of U.S. amateurs—led by University of Minnesota coach Herb Brooks—was impressive in the preliminary rounds, upsetting Czechoslovakia and West Germany to advance to the medal round. There, they had a date with the powerhouse Soviets, who had outscored their opponents 51–11 through their initial five games.

The first period went back and forth, with the Soviets taking 1–0 and 2–1 leads. In the period’s final seconds, Vladislav Tretiak, considered the world’s best goalie, misplayed a long slap shot. U.S. forward Mark Johnson gathered the puck and beat a sprawling Tretiak to tie the score just before time ran out. Frustrated, Soviet coach Viktor Tikhonov took his star goalie out of the game during intermission. His backup, Vladimir Myshkin, managed to hold the Americans scoreless in the second period, as the Soviets regained a one-goal lead. But the United States was not finished. The Americans stormed out in the third period, scoring on a power play; then team captain Mike Eruzione put in the go-ahead goal less than two minutes later.

U.S. goalie Jim Craig staved off a furious Soviet attack in the final minutes. With just seconds to go, the United States cleared the puck out of their offensive zone ascommentator Al Michaels asked the memorablequestion: “Do you believe in miracles?! YES!” The line was the inspiration for the game’s nickname.

The United States still had one game left, and the players proved they had one more comeback in them. Trailing Finland 2–1 after two periods, Team USA scored two goals within the first seven minutes of the thirdperiod to take the lead. They scored again with less than four minutes left, sealing a 4–2 win for the gold medal.

During his on-air commentary, Al Michaels asked: “Do you believe in miracles?! YES!” The line was the inspiration for the game’s nickname.

THE PUCK STOPS HERE: U.S. goalie Jim Craig was a star against the Soviets in the semifinal matchup.

MEN OF THE HOUR: The 20 men of Team USA shared a hug on the gold-medal podium. Their success lifted the spirits of the country in the face of many setbacks, including the national gas shortage, runaway inflation, and a hostage crisis.

A SNAPSHOT OF THE 1970s AND ’80s

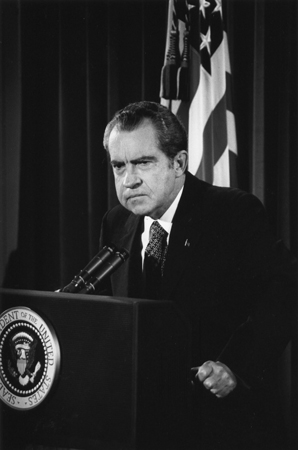

1972 WATERGATE On June 17, 1972, burglars were arrested inside the Democratic National Committee office. They were caught wiretapping phones and stealing documents. Their connection to President Richard Nixon, and his administration’s subsequent cover-up, led to Nixon’s resignation in 1974.

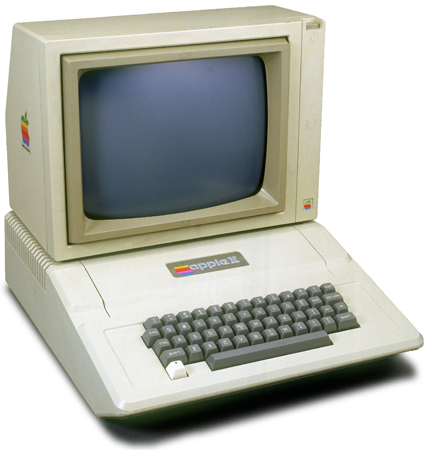

1976 THE BIRTH OF APPLE Steve Jobs, Ronald Wayne, and Steve Wozniak started Apple Computer Inc. and rolled out the Apple I, the first computer with a single circuit board. In 1977, they debuted the Apple II. The machine offered color graphics. It also included an audio cassette drive for storage.

1979 THE IRAN HOSTAGE CRISIS A group of Iranian students stormed the U.S. Embassy in Tehran and took more than 50 American hostages in protest of U.S. involvement in their country. The hostages were held for 444 days before being set free following an intense series of negotiations.

1989 THE COLLAPSE OF THE WALL In 1987, President Ronald Reagan called for Soviet Union leader Mikhail Gorbachev to open up the barrier that separated Democratic West Germany from Communist East Germany. Two years later, East Germans were allowed to cross the border, and ecstatic crowds used picks to tear down the Cold War symbol.

Britain’s first Olympic ski jumper became an unlikely folk hero when his unwavering determination landed him a spot in the 1988 Calgary Games.

…

Britain’s Michael Edwards dreamed of competing in the Olympics, but he faced a few obvious hurdles. For one, the plasterer from Cheltenham, England, was severely myopic. Second, there was no sport in which he was skilled enough to qualify for the Games.

A decent downhill skier, Edwards thought his best hope would be on the slopes. When he didn’t make the cut to represent Great Britain in the 1984 Games, he switched to a discipline that he had never really tried, ski jumping, where he thought his odds were better. The reason? Great Britain didn’t have another athlete that competed in the event.

Edwards moved to Lake Placid, New York, to train. Relying on hand-me-down equipment and a tireless spirit, the 24-year-old started to improve in his new sport as the 1988 Calgary Olympics approached. By the time the trials rolled around, he was still a neophyte, but the strategy paid off: Edwards qualified for the Great Britain Olympic team as its one and only ski jumper.

Arriving in Calgary, Edwards stood out among the community of elite athletes. He weighed 180 pounds, heavier than most of his fellow skiers, and his Coke-bottle glasses fogged up in competition. He was also self-deprecating. The combination of qualities, along with Edwards’s determination to be an Olympian, turned out to charm fans—especially his countrymen in the U.K., who dubbed him Eddie the Eagle for the way he looked flying off the ski jump.

That Edwards finished last in both of his events barely mattered. In his mind, he felt victorious just for representing his country in the Olympics and giving it his all. “Just sitting on that bar with my skis on, getting ready, I thought, ‘Well, this is it, I’ve made it to the Olympic Games,” Edwards later said.

In the months that followed, Edwards became a popular guest on talk shows around the world. He landed lucrative sponsorships and marched in a non-victory parade in his honor. He never competed in another Olympics. But he remained a folk hero to every kid who was ever picked last in sports or was told that they weren’t talented enough to make it. In 2016, Eddie the Eagle, a movie starring Taron Egerton and Hugh Jackman, brought the story of Britain’s most beloved Olympic failure to the big screen.

RARE AIR Edwards competed in the ski jump at the Calgary Games, finishing in last place in both events he entered. The high winds made the conditions especially dangerous, and organizers tried to convince the inexperienced Edwards to sit out.

A whimsical dream became Olympic reality when a group of athletes from a tropical island showed what it could achieve on ice.

…

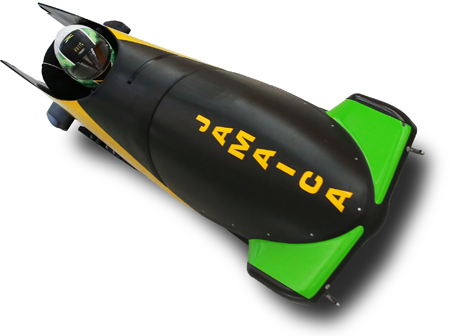

It all started with a dare. In 1987, American George Fitch, a member of the Foreign Service who worked in Jamaica, bet a friend he could find a winter sport in which local athletes could excel. Jamaicans were already world-class competitors in sports like track and field, so why couldn’t they do well in other sports too? So what if the temperatures on the island nation rarely dipped lower than the high 70s?

After attending a pushcart derby, in which contestants race homemade street-vendor carts, Fitch found his answer. Jamaica had plenty of athletes who possessed the lower-body strength and speed that would make them naturals at bobsledding, which requires strong push starts. Fitch put up his own money and decided to assemble a team. He first approached soldiers at the Jamaican Defence Force headquarters and found three stars: Dudley Stokes, a helicopter pilot who became the team captain, and Devon Harris and Michael White, both strong runners. He also recruited railway locomotive driver Samuel Clayton and student Caswell Allen, who later was injured and was replaced by Stokes’s brother, Chris. Rounding out the team was electrician and part-time reggae singer Frederick Powell. “I saw this thing on TV, and I said to myself, ‘Hey, mon, I got to do this thing. I never saw snow,’ ” Powell told People magazine before the Games.

American Howard Siler, a two-time Olympian as a bobsledder and a former U.S. national coach, was hired as their coach, and in September, the team set off for Lake Placid, New York. The Mount Van Hoevenberg run was the men’s first taste of the ice and snow. It was also terrifying. After a slippery start and an early crash, the team began to improve rapidly.

They passed an important hurdle in December 1987. The international federation required the Jamaicans to participate in a World Cup race. They finished a surprising 35th out of 41 nations, qualifying for the Calgary Games. The stage was set for Jamaica’s debut, and the world tuned in to watch the fun-loving bobsledders from the country that didn’t know snow.

It was an inauspicious beginning. The four-man team crashed, while the two-man team finished 30th. Yet the Jamaicans did not give up on the sport. The country participated in the 1992 Games in Albertville, and has competed in six Olympics, including the 2014 Sochi Games.

CHILL FACTOR The Jamaican bobsled team posed on the beach in Kingston, Jamaica. The team consisted of (from left) Michael White, Dudley Stokes, Devon Harris, and Frederick Powell, and inspired the popular 1993 movie Cool Runnings.

After the U.S. gymnast fell and sprained her ankle on her first vault attempt, she summoned her strength to try again, stick the landing, and help her team win gold.

…

CLUTCH PERFORMER At the 1996 Games, Strug badly injured her ankle on her first vault (above, first two photos), but helped the United States win gold when she stuck the landing on her second attempt (third photo).

The U.S. women’s gymnastics team seemingly had the gold medal in hand going into the final rotation of the team competition at the 1996 Atlanta Games. But then things started to go wrong. Competing on the vault, one by one, the U.S. team members struggled to land cleanly. When it was Kerri Strug’s turn, the 18-year-old Arizona native under-rotated on her first attempt, falling awkwardly. She heard something snap in her ankle. Suddenly, the gold medal was hanging in the balance, and a door was open for the Russians to win it all.

Strug was badly injured— she couldn’t feel her foot—but her team needed her and she readied herself for her final attempt on the vault.

“You can do it!” coach Béla Károlyi urged Strug, who was wincing in pain. “You can do it!” Strug took off running for a particularly difficult vault and remarkably stuck the landing on one foot and then hopped over to present to the judges that she was done. Then she collapsed in pain on the mat. As coaches helped her limp away, the scoreboard revealed her score: 9.712. The United States had clinched gold.

As the crowd roared, Strug, who was later diagnosed with a third-degree lateral sprain, was brought to a stretcher. While her teammates readied to take their spot atop the podium, Strug was on her way out to be taken to the hospital. In tears, she called out to Károlyi.

“No one’s taking you anywhere until you get your gold medal,” the coach responded. He then lifted her off the stretcher and carried her to the podium. Her teammates, waiting for her to join them, started toward the podium. Strug, in Károlyi’s arms, waved to the crowd.

Károlyi carried Strug to the podium to receive the team gold medal.

The man known for floating like a butterfly and stinging like a bee moved spectators to tears with his surprise appearance at the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta.

…

FULL CIRCLE Below: Legendary boxer and world statesman Muhammad Ali lit the Olympic flame to open the 1996 Atlanta Games, 36 years after winning a gold medal at the 1960 Olympics in Rome (above).

Arguably the most popular Olympian of the Games’ first 100 years was the legendary Muhammad Ali. When Ali passed away on June 3, 2016, he was more than a half-century removed from the 1960 Games where he first made his mark on the world. That year, he was an up-and-coming 18-year-old boxer in Kentucky going by his given name, Cassius Clay. Yet Clay was a kid so afraid of flying that he nearly skipped that year’s Olympics in Rome. Joe Martin, a local policeman who had encouraged Clay to learn to box, convinced him to make the trip. Clay supposedly wore a parachute throughout the flight.

By the end of that summer, Clay was a gold medalist whose unique style in the ring and magnetic personality away from it made him so well liked that he was known around Rome as the Mayor of the Olympic Village. “I didn’t take that medal off for two days,” he later said. “I even wore it to bed. I didn’t sleep too good because I had to sleep on my back so that the medal wouldn’t cut me. But I didn’t care, I was Olympic champion.” Throughout the rest of his career, Ali upheld the honor and ideals of being an Olympic champ and international ambassador. So it was fitting that at the centennial Games, held in Atlanta in 1996, the great champion would be at the heart of another great Olympic moment.

The torch relay started with Rafer Johnson, the 1960 gold medal winner in the decathlon. Over the course of 12 weeks, the torch snaked across the country, from Los Angeles to Atlanta. The last person to carry the torch outside Centennial Olympic Stadium in Atlanta was four-time gold medal discus thrower Al Oerter. He passed it off to American boxing legend Evander Holyfield, who brought it inside and then gave it to Greek track star Voula Patoulidou. The two ran around the track together before handing it off to four-time gold medalist swimmer Janet Evans. Evans ran a lap and then ascended a ramp to the cauldron. That’s when Ali emerged as the final torchbearer.

Ali was in deteriorating health. Stricken with Parkinson’s disease, visibly shaking, and a far cry from the vibrant, outspoken champion he once was, Ali stood tall with the flame, a sight that moved many to tears. He lit a mechanical torch that was then transferred to the cauldron that sat atop a 100-foot tower, marking the start of the Games. The ovation for Ali was as loud as any he had ever received. The world cheered for achampion whose career in and out of the ring embodied the American values of conviction, dedication, and compassion.

He was a far cry from the vibrant, outspoken champion he once was. But Ali stood tall with the flame, a sight that moved many to tears.

A LEGEND IS BORN: Ali (center), then known as Cassius Clay, posed with fellow gold medalist boxers Eddie Crook (left) and Skeeter McClure (right). About a year later, Ali’s medal disappeared. Ali said that he threw it into the Ohio River after being refused service in a diner, though some believe the story is a myth.

1991 THE END OF THE U.S.S.R. In December, 11 Soviet republics announced that they would no longer be part of the Soviet Union, dissolving the communist nation. Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev’s policies of perestroika and glasnost (restructuring and openness) set the stage for the disbanding, which marked the end of the Cold War.

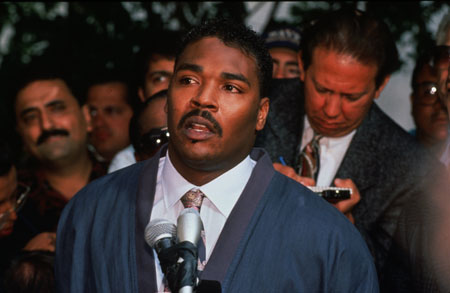

1992 LOS ANGELES RIOTS The acquittal of four Caucasian police officers who were shown on videotape beating African-American Rodney King sparked six days of violent riots throughout L.A. More than 50 people died before military forces were called in to stop the looting and rioting.

1995 OKLAHOMA CITY BOMBING On April 19, a truck bomb exploded outside the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, leaving 168 people dead and hundreds more injured. The blast was set off by Timothy McVeigh, an anti-government military veteran.

1995 A NEW IRON MAN The Baltimore Orioles’ Cal Ripken Jr. broke New York Yankees legend Lou Gehrig’s streak of consecutive games played when he appeared in his 2,131st game on September 6. Ripken extended the record to 2,632 games before finally sitting out a game in 1998.