…

POOL SHARK Michael Phelps swam the butterfly leg of the 4 × 100 individual medley relay at the 2008 Olympic Games. The United States went on to win gold in world record time, giving Phelps his record eighth gold medal.

GREEK FIGHTER THEAGENES OF THASOS WAS ONE OF THE FIRST RENOWNED Olympic athletes, undefeated in 1,300 matches, including competitions in the 75th Olympiad in 480 BC and the 76th Games in 476 BC. After Theagenes died, his hometown erected a statue in his honor. According to mythology, one bitter rival returned to the statue every night to beat it up. Eventually, the statue fell on the man and killed him, burnishing Theagenes’ Olympic reputation even in death. In the more than 2,000 years that have passed, other exceptionally talented athletes have joined the ranks of Olympic legends. We celebrate a few of the greatest.

As a child she was sickly and unable to walk. As an adult she was one of the most graceful athletes to set foot on the track, defying the odds to become an Olympic champion and icon.

…

Rudolph warmed up before her races at the Rome Games.

The 20th of 22 children to Ed and Blanche Rudolph, Wilma Rudolph weighed four and a half pounds at birth and remained frail in her early youth. At age 4, she contracted pneumonia, scarlet fever, and polio, which caused her left leg to be paralyzed. But the young Tennessean refused to stay bedridden: At 6 years old, she learned to hop on one leg and began to walk with a leg brace. Her mother, a maid, drove her 90 miles each way for weekly physical therapy visits. By age 11, Rudolph was playing basketball without her brace, and she soon blossomed into a 5' 11" sports star.

Rudolph was a talent on the basketball court, but she became a legend in track. As a 16-year-old in 1956, she made the U.S. Olympic team, winning bronze in Melbourne as part of the 4 × 100 relay team. Four years later, at the Games in Rome, she became the first American woman to win three gold medals in track in one Olympics. After retiring from racing in 1962, Rudolph leveraged her fame to fight for civil rights and feminist causes.

HOME STRETCH Rudolph won the 100-meter dash, the 200 meters, and the 4×100-meter relay, breaking world records in all three competitions at the 1960 Rome Olympics.

WHEN IN ROME A CLOSER LOOK AT RUDOLPH’S EPIC PERFORMANCE AT THE 1960 OLYMPICS

100 METERS

Despite injuring her ankle the previous day, Rudolph equaled the world record during her semifinal run, leaving no doubt that she would be the favorite entering the finals. With temperatures in the triple digits, Rudolph scorched the field, finishing in 11 seconds.

4×100-METER RELAY

The U.S. team was represented by Rudolph (left) and her teammates from Tennessee State University, (from right) Barbara Jones, Lucinda Williams, and Martha Hudson. The quartet, with Rudolph running the anchor leg, set a world record in the preliminary heats (44.50 seconds). The final was not nearly as easy. The United States led until Rudolph fumbled the baton. She had to make up about two yards and edged out the German runner at the finish line.

200 METERS

Just a day after winning gold in the 100 meters, Rudolph set a new Olympic record in the preliminary heats for the 200 meters, with a time of 23.30 seconds. She was slowed by a stiff headwind in the finals, but Rudolph easily captured her second gold medal of the Games.

A LASTING LEGACY

After her achievements at the 1960 Games, Rudolph took part in a European tour before returning home. She was honored with a homecoming parade and banquet in her hometown of Clarksville, Tennessee, and insisted the celebration be integrated, one of the first such events in Clarksville’s history.

On top of her athletic feats, Rudolph represented something much greater. She was an African-American woman whose victories in Rome came during the civil rights movement and second-wave feminism.

“She was the Jesse Owens of women’s track and field, and like Jesse, she changed the sport for all time,” said Olympic historian Bud Greenspan. “She became the benchmark for little black girls to aspire.”

Rudolph ran her last race in 1962. She became an elementary school teacher and track coach, while also working with underprivileged kids through the Wilma Rudolph Foundation. U.S. Vice President Hubert Humphrey enlisted her to work in Operation Champ, a program in which star athletes worked with kids in inner cities. In 1974, she was voted into the National Track and Field Hall of Fame. Twenty years later, Rudolph died at age 54 after battling a brain tumor.

CLAIM TO FAME: Rudolph signed autographs at a Berlin department store in 1972. After she retired from competition, she devoted her time to working with children and became a sports commentator. In 1983, Rudolph was inducted into the U.S. Olympic Hall of Fame.

The speed skater and reluctant hero accomplished what no athlete had ever done in the history of the Winter Olympics: He won every single event in his sport.

…

In racing sports, sprinting champions usually do not compete in endurance events, and vice versa. In track and field, for example, the winner of the 100-meter dash would not later enter the 5,000-meter race.

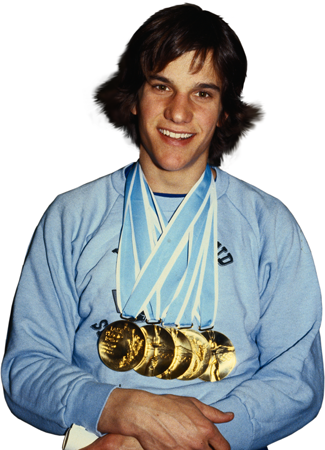

But the 1980 Lake Placid Games were not business as usual, thanks to extraordinary U.S. speed skater Eric Heiden. The 21-year-old Heiden not only swept all five speed skating events—distances that ranged from 500 to 10,000 meters—he won the most individual gold medals ever in a single Winter Olympics.

Heiden kicked off his gold medal run with a victory in the 500 meters. The sprint was his weakest race, but Heiden pulled away at the end to win in an Olympic record 38.03 seconds. The next day he won the 5,000 meters, and he followed that up with victories in the 1,000 and then the 1,500. Eight days after his first race, Heiden was in position to complete the sweep, as he prepared for the 10,000 meters. The day got off to a rocky start. Having stayed up late to watch the U.S. hockey team upset the Soviet Union in the Miracle on Ice game, Heiden overslept the next morning. But the 21-year-old didn’t miss a step. He won in 14 minutes, 28.13 seconds, shattering the world record by 6.2 seconds. The silver medalist didn’t complete the race until 7.9 seconds after Heiden crossed the finish line.

Heiden was a bona fide hero in the rink but never basked in Olympic glory. “I didn’t get into skating to be famous,” he once said. A few years after Lake Placid, the Wisconsin native became a professional racing cyclist. In 1985, he won the first U.S. Professional Cycling Championship as a road race champion. The following year, he participated in the Tour de France, but crashed five days from the finish and failed to complete the race. After his career in sports came to an end, Heiden earned a medical degree from Stanford University and became an orthopedic surgeon.

HIGH FIVE Heiden pulled ahead to win the 500-meter sprint, the first of his five gold medals at the 1980 Games. He and world record holder Yevgeny Kulikov were locked in a tight race until Kulikov slipped coming out of the last curve.

In a career that spanned four Olympics, the track-and-field star broke numerous records in the long jump and reached new speeds on the track.

…

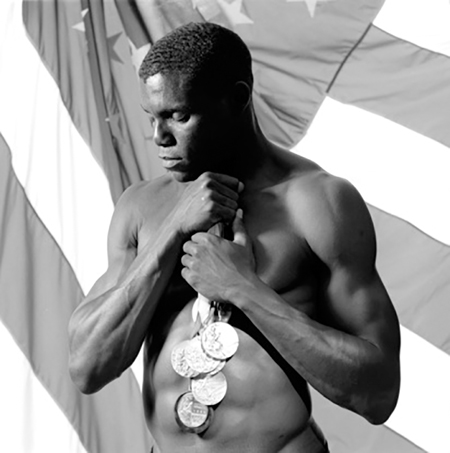

Lewis posed with his Olympic medals. He won gold in the long jump in four consecutive Games.

Growing up in Willingboro, New Jersey, in the 1960s and ’70s, Carl Lewis was a well-rounded student, taking cello and piano lessons and participating in sports. Track and field was the family calling. His parents, William and Evelyn, coached a track-and-field club, and Evelyn was a former elite hurdler. Both Carl and his sister, Carol, showed promise in the long jump from an early age.

By the time Lewis reached his senior year in high school, he had improved his personal best in the long jump by nearly a foot and was among the top five competitors in the world. At the University of Houston, he became a world-class sprinter, winning the 1981 National Collegiate Athletic Association title in the long jump and the 100-meter race. As only the second person ever to accomplish the feat, he was named top amateur athlete of the year.

Lewis introduced himself to the world at large in 1983 at the international track and field federation’s first world championships. Crushing the competition in the 100 meters and the long jump, Lewis demonstrated the speed and endurance that would define his Olympic career. He made his Olympic debut at the 1984 Los Angeles Games and continued to generate headlines for the next three Olympics. He eventually won a total of 10 Olympic medals, nine of which were gold.

SPEED RACER: Lewis ran the anchor leg of the 4×100 relay at the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics, leading the U.S. to victory in world record time.

The 1992 U.S. Olympic basketball team was filled with NBA legends—and dominated the competition on its way to gold.

…

LIFTOFF Guard Michael Jordan went up for a dunk at the 1992 Barcelona Games. It was the first Olympics that allowed NBA players to compete. The United States beat its eight opponents by an average of 44 points a game.

For 52 years—from basketball’s debut as an Olympic sport in 1936 through 1988—the United States sent only college amateurs to compete in the sport at the Games. Even though other countries featured more seasoned players, the United States still won gold nine out of 12 times.

But in 1988, after the Soviet Union beat Team USA in the Olympic semifinals, fans lobbied U.S. officials to change its policy and send the country’s best to the Games. Recognizing that other nations had caught up to the United States in basketball talent, the International Basketball Federation (FIBA) agreed to allow professional players from the National Basketball Association to take part in the 1992 Barcelona Games.

At first, the NBA was hesitant. What if a superstar were to get hurt during the Olympics? And was it right to break from tradition since the Olympics had become a showcase for the nation’s best college players? Eventually, and after much debate, the league became excited by the idea that basketball fans had already embraced—the thrill of watching the NBA’s best athletes from across the league playing together on one team on a world stage.

Twelve players were chosen (see outlined section on the following pages) and the squad was nicknamed the Dream Team.

During the Olympic tournament, Team USA showed no mercy. They won their opening game over Angola 116–48. “They should be happy to be here,” quipped forward Charles Barkley after the game. “They’regoing to be the answer to a trivia question.”

The Dream Team continued to cruise straight to the gold medal game against Croatia. That matchup proved to be closer than expected. The Croatian team even held a 25–23 lead midway through the first half. But it didn’t last long. The Dream Team had a 14-point advantage by halftime and won the game 117–85 for the gold medal. The United States reestablished its dominance in the sport that it had invented.

THE DREAM TEAM

THE GREATS WHO LED THE UNITED STATES TO GOLD

1. MICHAEL JORDAN, GUARD, CHICAGO BULLS (back row, in jerseys starting at left)

Considered the greatest player of all time, Jordan won five regular-season MVP awards, is the only player to be named NBA Finals MVP six times, and is the NBA’s all-time leader in scoring average.

2. LARRY BIRD, GUARD, BOSTON CELTICS

The sharp-shooting Bird won three MVP awards and led the Boston Celtics to three NBA titles.

3. MAGIC JOHNSON, GUARD, LOS ANGELES LAKERS

Johnson, a three-time NBA MVP, led the Los Angeles Lakers to five NBA titles. He retired before the 1991–92 season after testing positive for HIV, but played in Barcelona and later played 32 games in 1995–96.

4. CHRIS MULLIN, FORWARD-GUARD, GOLDEN STATE WARRIORS

A five-time All-Star, Mullin was a dangerous shooter and one of the NBA’s top all-around players.

5. CLYDE DREXLER, GUARD, PORTLAND TRAIL BLAZERS

Drexler, nicknamed Clyde the Glide for his smooth moves, was a 10-time NBA All-Star and had his No. 22 jersey retired by both the Portland Trail Blazers and the Houston Rockets.

6. JOHN STOCKTON, GUARD, UTAH JAZZ

The NBA’s all-time leader in assists and steals, Stockton was a 10-time All-Star.

7. SCOTTIE PIPPEN, FORWARD, CHICAGO BULLS (front row, in jerseys starting at left)

Pippen won six NBA titles and was a seven-time All-Star and eight-time all-defensive first team selection.

8. CHRISTIAN LAETTNER, CENTER, DUKE BLUE DEVILS

The only college player on the team, Laettner led Duke to back-to-back national titles in 1991 and ’92 and won national player of the year honors in ’92.

9. PATRICK EWING, CENTER, NEW YORK KNICKS

Ewing was an 11-time All-Star and the New York Knicks’ all-time leading scorer.

10. CHUCK DALY, COACH, NEW JERSEY NETS

The Dream Team’s head coach led the Detroit Pistons to back-to-back NBA titles in 1989 and ’90. Joining him as assistants were Duke coach Mike Krzyzewski (back row, left), Atlanta Hawks coach Lenny Wilkins (back row, second from left), and Seton Hall coach P.J. Carlesimo (back row, second from right).

11. DAVID ROBINSON, CENTER, SAN ANTONIO SPURS

The center was a 10-time All-Star and the 1991–92 Defensive Player of the Year. He won two NBA titles with the San Antonio Spurs.

12. KARL MALONE, FORWARD, UTAH JAZZ

Nicknamed the Mailman for his ability to deliver, Malone was a two-time NBA MVP.

13. CHARLES BARKLEY, FORWARD, PHOENIX SUNS

The outspoken Barkley was the NBA MVP in 1993 and one of the game’s greatest rebounders.

No athlete in history has had a more appropriate surname than Jamaica’s sprinting sensation.

…

LIGHTNING STRIKES This image shows the precise moment when Bolt crossed the finish line in the 100-meter sprint at the 2012 Olympic Games. Bolt won easily in 9.63 seconds, the second-fastest time in history.

Usain Bolt proved he was the fastest man on the globe at the 2008 Beijing Games. He won gold in the 100- and 200-meter races and was part of the winning 4×100-meter relay team, setting world records in all three events. Bolt won three more golds in those events at the 2012 London Games. Scientists consider his body and running form miracles of human biomechanics. Here’s a look inside the numbers.

6'5"

Bolt’s height

207 lbs

Bolt’s weight

3

Times that Bolt has broken the world record in the 100 meters

9.58 seconds

Bolt’s world record time in the 100 meters at the 2009 world championships. He broke his own record of 9.69 seconds.

5.29 seconds

Amount of time Bolt was not touching the ground during that 100-meter race

27.79 miles per hour

Bolt’s speed between the 60- and 80-meter marks while running his 9.58-second 100-meter dash

1,000 pounds

Approximate force with which Bolt pushed off on each step, according to physiologist Peter Weyland of Southern Methodist University. Most people apply about three times their body weight when sprinting.

The swimming phenom astonished fans around the globe by winning eight gold medals and setting seven world records at the 2008 Beijing Olympics.

…

Mark Spitz’s feat of winning seven gold medals at the 1972 Munich Games loomed large over other athletes, especially swimmers, for more than 30 years. But entering the 2008 Beijing Games, swimming phenom Michael Phelps decided he wanted to win eight.

Phelps already had an impressive résumé at the Games, winning six gold medals and two bronzes in 2004, so challenging Spitz’s record did not intimidate him. “Records are made to be broken,” he said, “no matter what they are.”

At the start, Phelps made the Herculean task look easy. He won his first race, the 400-meter individual medley, in a world record time of 4:03.84. Silver medalist Laszlo Cseh of Hungary finished more than two seconds behind. Phelps’s performance is even more impressive when you consider that Cseh’s time was good enough to set a new European record.

Phelps continued to set world records in his next five races: the 4×100-meter freestyle relay, the 200-meter freestyle, the 200-meter butterfly, the 4×200-meter freestyle, and the 200-meter individual medley.

But things got a little tougher in Phelps’s seventh race, the 100-meter butterfly. Perhaps it was the added pressure of knowing he was swimming to tie Spitz’s record. Or maybe it was simply the quality of his competition. Serbian Milorad Cavic jumped out to an early lead, and Phelps swam to catch up the entire race. To many spectators, it even appeared that Cavic beat him to the wall. But while Cavic glided to his finish, Phelps lunged forward with an additional stroke. Thanks to his long reach, Phelps touched the wall first, winning by one-hundredth of a second. Phelps had tied Spitz by a fingertip.

Phelps’s final race was the 4×100-meter individual medley. Swimming the third leg, he jumped into the pool with his team in third place but handed the Americans the lead. Team USA held on for Phelps’s eighth gold.

STILL GOLDEN Phelps celebrated in the water after winning the 100-meter butterfly by a fingertip at the 2008 Olympics. He out-touched Serbian Milorad Cavic at the wall for his seventh gold of the Games.

A FISH OUT OF WATER

THE FACTS AND FIGURES BEHIND THE GREATEST SWIMMER OF ALL TIME

76 inches tall

80-inch wingspan

Most of the time, a person’s height corresponds closely to the distance between his outstretched hands. By this measure, Phelps has an extra four inches in his wingspan. His long arms give him more power in his strokes, and the reach gives him an edge in close races.

12,000 calories consumed a day

During the 2008 Beijing Olympics, Phelps said his daily meals included a breakfast of three fried-egg sandwiches, a five-egg omelet, three pieces of French toast, three pancakes, and grits. Lunch was typically a pound of pasta and two sandwiches. For dinner, he would eat an entire large pizza and a pound of pasta.

Extreme Flexibility

Phelps’s knees and elbows have a greater range of motion than the average swimmer. That flexibility allows him to whip his arms and feet, propelling him forcefully through the water.

Produces 50% less lactic acid than other athletes

Phelps’s body recovers quickly after a race because his muscles produce half the amount of lactic acid, which causes muscle fatigue, than most of his competitors. While the typical athlete needs a long rest period, Phelps bounces back to top form just minutes after a grueling race.

Size 14 feet

Phelps’s feet reportedly bend 15 degrees farther at the ankle than those of other swimmers, turning his feet into virtual flippers.

The gymnast blasted onto the scene, making history at the 2012 Games as the first African-American to win individual all-around gold in her sport.

…

Three-year-old Gabby Douglas always loved tumbling around the living room. Her older sister, Arielle, taught her how to do a cartwheel and not long after,Gabby figured out how to do it one-handed. When she was 6, she started formal gymnasticslessons, rising through the ranks in her home state of Virginia. The story could have ended there, as it does for many young gymnasts. But at age 14, Douglasdecided to move to Des Moines, Iowa, to work withrenowned coach Liang Chow. Fourteen is young for most things, but old if your goal is to become a world-champion gymnast.

The transition from local star to Olympic hopeful wasn’t easy for Douglas. She lacked precision but overcame her technical deficiencies with boundless energy. Douglas soared so high on the bars that coaches nicknamed her the Flying Squirrel. Her work ethic was also strong. At the 2012 national championships—less than two years after leaving Virginia—Douglas showed how far she had come. She won gold on the bars, silver in the all-around, and bronze on the floor. Two weeks later at the Olympic trials, she won the all-around, which guaranteed her a highly coveted spot on the U.S. Olympic team for the 2012 London Games.

Douglas and her teammates McKayla Maroney, Aly Raisman, Kyla Ross, and Jordyn Wieber were medal favorites nicknamed the Fierce Five. With Douglas leading the way, the quintet delivered on the hype. The United States won the team event for just the second time in U.S. gymnastics history.

Two days later, Douglas took the spotlight alone in the individual all-around competition. The Flying Squirrel opened with an impressive performance on the vault and never looked back. She secured the gold medal with a near-flawless beam routine and strong showings on the floor and bars. “A lot was going through my mind,” Douglas said. “I was like, ‘Yes, all the hard work has paid off.’ I was speechless. Tears of joy and just waving to the crowd.”

Douglas became the third consecutive American to win the women’s individual all-around. She was also the first African-American woman to accomplish the feat. Said national team coordinator Márta Károlyi: “I don’t ever recall anybody this quickly rising from an average good gymnast to a fantastic one.”

BALANCING ACT Douglas performed a flip on the beam in the individual all-around competition at the 2012 Olympics. Her nearly perfect routine helped her secure gold.