Expressionist Dial

Or, Thinking Around Canonicity

As an object-maker, Thornton Dial is unparalleled. Though comparisons are made with other southern African American artists, from Hawkins Bolden from Tennessee to his fellow Alabama residents and friends like Lonnie Holley and Ronald Lockett, none possesses quite the mixture of touch, artistic intelligence, skill as a manipulator of his media, and sheer empathic understanding of what it takes to choose subject matter and bring it together in a poetical and utterly convincing manner. His drawings are a distinct and important stream, less complex and forthrightly physical than, though not subservient to, the larger and more worked paintings and constructions. For the viewer, they reveal the distilled essence of his creative approach. Through them, much can be learned about his creative thinking, separated from other more technical and narrative concerns that are important in the other parts of his practice. Taken together, Dial’s work amounts to a significant oeuvre, whether measured in terms of content or aesthetic quality. In truth, the two are inseparable.

Watching Dial draw is like watching movies of Jackson Pollock, Arnulf Rainer, or Karel Appel in his later years working. In each case, there is a highly intuitive though decisive approach to mark-making that simultaneously takes account of materials, ground, and emerging subject. Dial’s drawing activity is anchored by a stock of forms: fish, birds, serpentine cats, female faces, and contorted, open-form women. On one level, this means that although each drawing can be read individually, as if rendered for the first time, the cumulative works are effectively an ongoing series. Alternatively, we might view the stock of forms as analogous to cords put in the service of a spare musical form that relies on repetition of sequences and recognizable melodic structure yet also delivers a rich and sophisticated formal and narrative content.

The drawings are the microcosm of a practice that, for Dial, begins in all media with the broad idea (“the pattern,” as he calls it) but privileges development of the completed work through intuitive manipulation of materials, relying on the peculiarly visceral cognition embedded in hand and eye. Dial’s is essentially an expressionist modality, akin to that described by Henri Matisse as long ago as 1908: “The thought of a painter must not be considered as separate from his [sic] pictorial means. . . . I am unable to distinguish between the feeling I have about life and my way of translating it.”1 Similarly, for Dial, the successful work must literally embody the person of the artist, transmogrified through the materials. As he himself put it: “The piece is going to have Mr. Dial in it, under it, and over it, and everybody can know it.”2 In “Notes of a Painter,” Matisse argued that although artists are driven by a singular goal, every new work they make is effectively a unique experience: “My destination is always the same but I work out a different route to get there.”3 Dial shares this experiential sense of the creative process, explained by him in terms of a metaphor for the constantly nascent creation of the world: “A piece of art is like the movement of the clouds, or the sun in the sky . . . constant moving, always changing. The movement of the world always make changes in things.”4

Dial has an organicist, essentially metaphysical attitude toward his materials, including found objects, that reflects expressionist beliefs: “Everything I pick up be something that done did somebody good in their lifetime. So I am picking up on their spirit.”5 Dial’s eschewing of the new and unused began as simple necessity, born of poverty, but it quickly became self-consciously part of his creative process. His interest in the broken and discarded object is both aesthetic and empathic. Each object is an accumulation through use of significant human experiential and emotional content: “I only want pieces that have been used by people, the works of the United States, that have did people some good but once they got service out of them they throwed them away. So I pick it up and make something new out of it.”6

Similarly, Dial invests in the manipulated material a communicative power beyond semiotics. Art-making, therefore, has to be conducted as active and physical and sensuous. He tells us: “I like to touch every picture all over the surface of it. It got to be a finished product. I like to work on that surface, rub it, scratch it, smear it. I beat on it sometimes, knock holes in it. I have even set fire to it. I want that finished piece to be exactly right when it leave my hands.”7 While this is perhaps more obvious in his great collage-paintings and constructions, it is no less part of his practice in his drawings, where economy of materials only emphasizes the physicality of the creative process: “I have learned to make a beautiful picture by just using pencil and charcoal. The rubbing and the smearing is the struggle to make something beautiful with your own hands.”8

Dial shares a concern with freedom, both as personal creative liberation and as social justice, with expressionists throughout the twentieth century, from Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Conrad Felixmüller early on, to Appel, Constant, Asger Jorn, Robert Motherwell, and Hans Hofmann in midcentury, and Georg Baselitz, A. R. Penck, and the Neue Wilde group near its end. “My art is evidence of my freedom,” he says. “When I start any piece of art I can pick up anything I want to pick up. . . . I start with whatever fits with my idea, things I will find anywhere. I gather up things from around. I see the pieces in my mind before I start, but after you start making it you see more that need to go in it.”9

Writing of the American abstract expressionists, the writer and critic Clement Greenberg pointed to the dynamic at play in their works between the privileging of gesture, or the physical act of art-making, against premeditation: “Their paintings startle because, to the uninitiated eye, they appear to rely so much on accident, whim and haphazard effects. An ungoverned spontaneity seems to be at play. . . . All this is seeming.” The good work, he argued, “owes its realization to a severer discipline than can be found elsewhere in contemporary painting.”10 The results in expressionist art are often visually awkward or ugly. Dial himself is aware of this predicament: “Art is strange-looking stuff and most people don’t understand art. Most people don’t understand my art, the art of the Negroes, because most people don’t understand me, don’t understand the Negroes at all. If everybody understand one another, wouldn’t nobody make art. Art is something to open your eyes. Art is for understanding.”11

To argue for Dial as expressionist is to attempt to appropriate him not to a historical movement but rather to something more generally understood as a creative tendency, of which German Expressionism or American Abstract Expressionism are only the most theorized and self-conscious examples. Even in its narrow, early modernist manifestation, the term “expressionism” was first used in France to describe the practice of post-impressionists and Fauves and adopted before 1918 in Germany as a pan-European designation. In the United States in 1934, the writer Sheldon Cheney in Expressionism and Art argued that expressionism was the common feature of international modernism. At its most useful, though, the idea of expressionism is divorced from the external application of social theory and generated through the practices and beliefs of individual artists.

Dial’s ability to produce compelling forms and to communicate strong messages directly has resulted in clear interest in his work. He has been the subject of three major monographs and numerous solo exhibitions, as well as included in many group shows. There are plenty of positive reviews and newspaper articles. His work is collected. He became a canonical figure soon after his work first came to public notice. From the specific point of view of the dominant contemporary art world, however, his canonical status has tended to be limited to noncanonical categories. Faced with an artist who was clearly highly intelligent and completely committed to his practice but whose formal education was negligible and who had appeared, as it were, from nowhere, Dial was inscribed into discourses of ethnicity, the self-taught, outsider, and the vernacular, a tendency further fuelled by formal similarities in his practice to some canonical outsiders. Perhaps most notable in the context of his drawings are comparisons with Europeans like Heinrich Anton Müller (fig. 2.1) or Gaston Duf, though these arise from a shared intuitive approach to image-making rather than any actual influence. His exhibition history confirms this, consisting characteristically of shows with outsider and vernacular themes,12 often in venues associated with non–art world art, including commercial galleries specializing in outsider or folk art.13 There are exceptions, to be sure. The most important are two solo shows, at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (2005), and the Indianapolis Museum of Art (2011).14 But even here the difficulty in presenting Dial matter-of-factly as contemporary artist continues, and issues around mainstreaming the vernacular pervade these museum shows and the critical response.

Figure 2.1 Heinrich Anton Müller, Untitled (between 1917 and 1922). Pencil and chalk on colored paper. 78 × 82 cm. Photograph by Henri Garmond. Courtesy of the Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne.

With seminal works like Patterns: Road Map of the United States (1992) (fig. 2.2), Trophies (Doll Factory) (2000) (fig. 2.3), and Cotton Field Sky Still on Our Head (2001) (fig. 2.4) to his name that speak to crucial historical and cultural content, as well as possessing more universal aesthetic qualities, how can America not see Dial as one of its great contemporary artists? How can his work not be found in the collections of the world’s great contemporary art museums? Why is this contemporary of the great postwar generation of artists like Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, and Karel Appel not in their pantheon? The answer to the last question is partly that, whereas the other three embarked on their careers in their twenties, achieving wide recognition early on,

Figure 2.2 Thornton Dial, Patterns: Road Map of the United States (1992). Wood, tin, enamel, and Splash Zone compound on canvas on wood. 56 × 78 ½ × 2 inches. Courtesy of the Mendlesohn Collection.

Figure 2.3 Thornton Dial, Trophies (Doll Factory) (2000). Barbie dolls, stuffed animals, plastic toys, cloth, tin, wood, rope carpet, Splash Zone compound, oil, enamel, and spray paint on canvas on wood. 75 × 123 × 18 inches. Courtesy of the Collection of Jane Fonda.

Figure 2.4 Thornton Dial, Cotton Field Sky Still on Our Head (2001). Toys, polyester fiber, cotton, cloth, baskets, wire screen, twine, wire, paint bucket, tin, bracelets, oil, enamel, and spray paint on canvas on wood. 72 × 87 × 10 inches. Courtesy of the artist and The Souls Grown Deep Foundation.

Dial was in his late fifties when he fully embraced his calling as artist, after forty years of blue-collar toil.

Coincidentally, there are some interesting correspondences between the practices of Dial and the other three. There is a tendency in Dial, for example, to appropriate the real and literally inscribe it into the fabric of his art—as with Rauschenberg’s combines, much of Appel’s sculpture, and, in a much more obviously self-critical way, Johns’s plays on metonymy in painting and sculpture. Similarly, the serial, intuitive form-playing in Dial’s drawings has analogues in the work of Rauschenberg and Appel. However, by the time Dial emerged onto the art scene around 1990, the way in which he breathed his art to life was rather unfashionable, sharing many more affinities with European art informel artists like Jean Dubuffet and Jean Tinguely in the decades after the Second World War than the increasingly dominant neoconceptualists of the last two decades of the twentieth century. So Appel, Johns, and Rauschenberg, as surviving old masters of the 1940s and 1950s, their reputations confirmed, continued to enjoy successful careers. Their already historical status insulated them, as it were, from arguments about what it took in the 1990s to be “cutting edge” in contemporary art. This was something unavailable to Dial as a newcomer to the scene.

Moreover, the neo-expressionism of the 1980s, epitomized by Julian Schnabel, Sandro Chia, and Anselm Kiefer, to which Dial’s work has its most immediate visual similarities in American art, had been stopped in its tracks. Its (anti)theoretical underpinnings had been called to account in the course of the decade by critics like Hal Foster, Craig Owens, and Benjamin Buchloh, and its market value was negatively impacted more than most by the financial crash of the late 1980s. The reputations of once-stellar younger artists like Schnabel and Chia dipped spectacularly, and postconceptual art gained an ascendance that is yet to be toppled. The dominant art world likes its contemporary artists young, photogenic, savvy, and art school educated. Its new stars were postconceptualist young guns like Jeff Koons, Damian Hirst, and Tracey Emin, and increasingly photo and new media artists (this was the decade that saw the reputations of artists like Cindy Sherman, Robert Mapplethorpe, and William Wegman confirmed in art history). So Dial’s arrival on the scene, at the mature age of sixty-two, has to be seen in this context.

With this as the background, in this essay I explore issues of canonicity, especially as they pertain to Dial and outsider art, and offer another reading of the artist that addresses artistic production headon and also problematizes the mainstream/outsider dichotomy. Dial’s first, and still most important, collector was William Arnett, who since the 1980s specialized in art of the African American South, having previously collected non-Western work, including pre-Columbian art, the art of India and Southeast Asia, and African art. Arnett was introduced to Dial by Lonnie Holley, a younger African American artist already well known in the self-taught scene. The immediate groups to which Dial’s practice was revealed were folklorists and others with interests in self-taught and outsider art. It is unsurprising therefore that Dial’s early exhibition outings and the first critical literature on the artist came from this quarter. He was recognized from the start as important, with early work that was sustained and impactful, without the formative juvenilia usually associated with an artistic career. This lack of a specifically artistic personal history was a positive criterion in the field of folk and outsider art, but it would prove problematic to his reception by the dominant, metropolitan contemporary art world.

In the 1990s, Arnett and others began an attempt to attract support for southern African American “vernacular” artists like Dial, Holley, and Ronald Lockett in the major cultural institutions and among curators and critics of contemporary art. But they were fraught with disappointment and resistance from what Arnett describes as an “institutional artworld profoundly ill-equipped to support these artists and the ideas their work embodied.”15 However, herein lies the paradox of Dial’s reputation and reception history: while he and his practice remain the same, Dial’s discovery, interpretation, and advocacy by one group alienates the other. From a contemporary art point of view, it is, sadly, something of a question of who got to Dial first. His career pattern does not conform to art world expectations, and he is culturally distant from the mix of curators, writers, dealers, collectors, and art producers who constitute and inhabit it. In view of this, as a self-taught southern African American working in Alabama, far from any of the dominant art world centers, he would be destined to remain invisible to that art world. His “discovery” by the folk/outsider art world—and it is almost certain that his initial discovery could only have been in the context of that field, precisely because its view is acentric—and championing from that quarter marginalizes him even as it makes him visible to broader art world contexts.

It has been suggested by many that the significant question is how to bring about Dial’s invasion of the dominant art world. But the question as to whether the artist should be appropriated by the dominant art world is also highly pertinent. What are the motivators? Part of the problem is a closedness of definition. The field of outsider art and its tributaries narrow the scope of opportunity in considering individual practices, and also dwell overmuch on anthropology at the cost of aesthetics. Institutionalized conversations about contemporary art, on the other hand, still owe much more to modernism and modernist theorizing than anyone wants to admit. They are situated within philosophical structures that are more interested in the way art relates to, and is affected by, other art (in a trajectory leading from Clement Greenberg and Michael Fried to Fredric Jameson), than as to how individual practices are constituted and function. In both cases, the effect is a kind of blindness that will not allow critics to see Dial in looser, more broadly creative terms, where affinities and common impulses within a range of practices might facilitate the development of a more holistic picture of Dial the artist.

Before suggesting strategies for approaching this, it will be useful to consider the construction of self-taught and outsider art, the field that first appropriated Dial as a public figure, his elevation to exemplary status within that field, and some of the ways in which his practice has been claimed and resisted in the nexus of art world posturing and debate. In the United States, the field’s first written formulation appeared in the 1930s with people like Sidney Janis and Holger Cahill,16 where it went under various guises, such as popular painting, modern primitive, self-taught, and contemporary folk art.17 In this formulation, artists were more likely to be autodidacts and more or less marginalized individuals (as often as not owing to their class and cultural positions). Early canonical self-taught Americans like John Kane, Horace Pippin, Morris Hirshfield, and William Edmondson emerged, especially as a result of championing by dealers and museum people, and not least by the seriousness such work was afforded by New York’s Museum of Modern Art in its first decade of existence.

There was, at least, a certain general art world interest in the American field that simply was not the case in Europe in the 1930s. However, if the works of the self-taught African American painter Horace Pippin found their way into the collections of mainstream art museums early on, Pippin still had no more chance of becoming a canonical figure in the dominant story of Western art than the institutionalized Adolf Wölfli in Europe, for example. As Judith McWillie has written, “It was a curious enigma to the fine arts intelligentsia of the 1930s that the aesthetic results of Africa’s fusion with the Americas . . . should so closely parallel, in some instances, works of the early modernists who, only a generation before, had experimented with their own version of Afro/European synthesis.” Yet, as she points out, the folk art designation won out over inclusion in mainstream, high art discourses, abetted by “folk arts enthusiasts, anxious to segregate themselves from what they called ‘the high art elite,” severely [criticizing] comparisons of American self-educated artists with European modernists.”18

William Swislow notes that

anyone with a passing exposure to the literature of outsider, self-taught, folk and related art has been exposed to the struggle to define a label equal to the richness of the art. Every few years a new word is floated and then shot down amid quotes from Jean Dubuffet, claims of elitism and questions of whether the work should be labeled at all. The effort is hopeless—not because the labels are wrong, but because the art does not constitute a single genre for which a universal label can be resolved. In different contexts, for different work, different, sometimes overlapping, labels will be appropriate.19

This has certainly been the case with Dial. Many have argued that Dial’s practice should be seen specifically in the context of African American self-taught or vernacular art and, as Jerry Cullum puts it, “shouldn’t be shunted off into categories reserved for the insane, the incarcerated, or the isolated and illiterate.”20 On the other hand, Tessa DeCarlo has argued for the usefulness and multivalent nature of the outsider denomination: “Why, then, fight the term outsider? If we want a name that refers primarily to the art rather than the artists, outsider makes more sense than the other candidates. It isn’t intrinsically insulting; everyone in America aspires to be an outsider, from pop stars to presidents.”21 Moreover, as Swislow says, “In the most useful version of the outsider art concept, the great insight is that art is not a monopoly of Culture, with a capital C.” In this sense, art produced outside the dominant art world matrix is generally recognized but not dependent on art world appropriation for legitimization. “The point,” says Swislow, “is certainly not that the art world’s light has finally shined to transform these objects into art.”22

Outsider art suffers from a powerful creation myth, first codified and promulgated in the mid-1940s by French artist and sometime wine merchant Jean Dubuffet, under the rubric Art brut. Around that time, he embarked on a flurry of art-collecting activity, most notably, though by no means exclusively, from European psychiatric hospitals.23 His aim was to seek out previously ignored and unvalued works that he considered to be of higher quality than any mainstream contemporary Western art, based on personal criteria that were a mixture of the (anti)aesthetic and sociological. The best artists, he argued, were those who were as unentangled from sociocultural influence as possible. This was because he believed, in line with an intellectual primitivism common at midcentury, that relatively unmediated creative outpourings reveal more truthfully the things of existence. Crucially, he also argued that although all such artists were probably better than any professional one, not all of them were necessarily of the highest quality. In this way, from the start, his artists—those represented in his collection; people like Heinrich Anton Müller, Adolf Wölfli, and Aloïse Corbaz, all of whom were long-term psychiatric patients; and Augustin Lésage, who was a spiritualist without artistic training—were held up as exemplary artistes-brut. Their status as artistes-brut was supported by a definition devised by Dubuffet that changed little from 1949 until his death in 1985,24 but which quickly gained the status of doxa in the European field. The contemporary field of outsider art, of which Art brut is a part, has its origins, though, half a century earlier25—indeed, Dubuffet had a kind of guidebook in his initial collecting activity in the form of Hans Prinzhorn’s Artistry of the Mentally Ill, published in German in 1922.

Dial can be viewed as a canonical figure in the subsets of southern African American vernacular art and outsider art, yet he has been more or less invisible in histories of contemporary art, in spite of the best attempts early on of supporters like Thomas McEvilley, himself a mainstream staple of New York art criticism and theory. The 1993 solo exhibition he curated, Thornton Dial: Image of the Tiger, seemed, for a time, to presage a grand entry for Dial into the contemporary art world. The openings were a great success, and there was talk of tours, Parisian shows, and acquisitions by major American collectors. However, McEvilley says, “I began to get phone calls about the Dial project, revealing a growing groundswell of resistance to it. Some of the calls were from prominent American museum directors.” Dial and other emerging southern African American vernacular artists like Holley, Lockett, and Bolden were perceived by many as a challenge to the cultural and aesthetic status quo of the dominant art world. While for some, like McEvilley, this was read positively as a symbol of a further breaking down of old exclusionary practices, for others it posed a threat to “cultural dominance.” In the end, he says, “the established white art world was made apprehensive by the threat that an important new group of artists was about to appear on the scene, a group completely outside establishment control.”26 So, instead, Dial’s work has been exhibited almost exclusively in minor mainstream spaces or ones devoted to outsider art.

There are instructive parallels with the British “outsider” Albert Louden. Here was another self-taught artist, this time from ordinary, working-class, East London origins who, through the efforts of the major contemporary art dealer Victor Musgrave and his partner, Monika Kinley, was given a major solo exhibition in London’s Serpentine Gallery in 1985, only a couple of years after his discovery. His highly inventive, personal visions of people and landscape received enthusiastic public praise. But the backlash from critics and art school–educated artists was vicious. Louden’s great unwitting sins were to have jumped the line, so to speak, for this prestigious contemporary space, funded by the British Arts Council, and to be applauded by his supporters as an outsider, which only served to further rankle professional sensibilities. Moreover, his outing in the mainstream has problematized the chimerical artistic purity demanded by Art brut’s apologists. Though troubled by all this, Louden is philosophical, and his practice remains the same.

Dial’s reception history explains his lack of visibility in the contemporary canon. In no small part, it is a result of his late emergence on the art scene, fully formed as an artist, but without a conventional personal artistic history. And, as previously stated, it is a result no less importantly of his embrace by the folk and outsider art fraternities, which marginalizes him in relation to the internationalist contemporary art world even as it accords him centrally important status in the former fields. Additionally, identification as outsider or vernacular implicates an artist in a market whose prices are much lower, so that even canonical status in that world ensures low ceilings relative even to minor contemporary art stars. Intriguingly, Amiri Baraka sees this as part of Dial’s (unwitting) challenge: “There is . . . a real fear that this art, brought into the mainstream en masse, would compromise the goofy price structure of the modern art world.” The question of the comparative quality of his work is also raised: “Like I said when I first saw Dial’s work, if his work gets hung up then a lot of other stuff would have to come down.”27 It is certainly true that if the work of Dial and other southern African American artists is really of the highest quality, when measured against art world contemporaries, then logically it demands a rethinking of the canon, which also implies the demotion of other artists. On the other hand, although Baraka is right to point to the issue of prices, the art market in general, and the contemporary art market in particular, influences as well as reflects the artistic value afforded to objects. The relatively low prices of southern African American vernacular art are a reflection not only of the discourse that supports it but also of the type of individuals and institutions that buy it; that is, on the whole, specialist collectors and not the mega-rich contemporary art collectors or major international museums. Were the latter groups to begin acquiring Dial’s work “en masse,” to use Baraka’s term, there is no doubt that his prices would rise accordingly in line with the contemporary art market.

In order to understand better Dial’s current art world position, it is worth examining the idea of the art historical canon more generally, since the canon abides despite attempts by various groups at times to rule it out of existence, while being simultaneously resistant to active manipulation of its meta-identity. The art historical canon refers, then, to those artists, tendencies, and groups that constitute the generally agreed list of representatives of the dominant flowering of art at any period in the West (or claimed for the Western tradition), as defined by a discipline—art history—that is itself little more than a century and a half old. By necessity, then, the proportion of canonical artists and artworks to those that are paradigmatic but noncanonical is small. Additionally, Christopher Steiner has noted, “the canon of art history is a highly routinized hierarchical system in which most non-Western arts have been relegated to the lowest status.”28 It might be added that local, nonhegemonic intra-Western arts have historically been of even lower status than most non-Western arts. Furthermore, Steiner says, “each subfield within the canon is itself a structured system which embraces certain categories of objects while rejecting many others.”29 In addition, other canons develop related to place, culture, and creative tendencies, so that while the North American modernist canon shares a number of agreed figures with the Northern European one, for example, it looks rather different. The former, though, owing to the cultural and political dominance of the United States in the contemporary era, is commonly accepted internationally. In the case of outsider art, however far away it might be perceived to be from the rarified heights of art history’s generally agreed pinnacle, it is implicated (in spite of much resistance by apologists and detractors alike) as a subfield and has its own canon.

British writer Steve Edwards notes that the art historical canon “is best understood as a relatively fluid body of values and judgments about art that are subject to constant dispute and redefinition.”30 This is the ground on which arguments about Dial’s place and importance can be played out over time: will the apparently increasing number of solo exhibitions in public museums contribute to a raising of his status in the overall art historical canon? Others argue more emphatically that “the canon of art history . . . is a rigid hierarchical system which excludes ‘impure’ categories of art and reduces certain classes of objects to the status of untouchable.”31 Interestingly, art history’s core figures and canonical works have remained relatively stable. More often than not, it is not the canon that shifts appreciably but the discourse around it. So, the canon has tended to morph around this core mostly in relation to changes in contemporary art world fashions or new discoveries in places in which cultural and political hegemony reside at any time (currently, for example, major international reappraisals of Chinese and Indian modern and contemporary art that are related directly to the recent economic rise to dominance of these nations are under way).

Crucially, as Rakefet Sela-Sheffy has argued, canons are “accumulative, widely shared and persistent cultural reservoirs, which endure the vicissitudes of dominant tastes promoted by different groups in different times.”32 This is what McEvilley and Baraka lament. It is partly a question of historical perspective, though. Canons are more precariously constructed the closer one gets to the present; a glance at any art history survey on contemporary art written in the middle of the last century containing dozens of seemingly canonical figures whose stars have since waned will demonstrate this. Dial is the same age as Jasper Johns and Andy Warhol, but his emergence as an artist three decades after them places him in a contemporary context. Dial is of the present, while they are already of the past and their legacy already seemingly secure.

Outsider art as a field really grew out of a coming together of the older American contemporary folk art tradition, Art brut and its tributaries in Europe, and a growing postwar American embrace of its own exponents of Art brut, so that nowadays it is starting to look something like a global phenomenon; so much so that it is not infrequently, though incorrectly, referred to as a movement qua impressionism, cubism, etc.33 Its name, as is well known, can be traced to the title of Roger Cardinal’s 1972 book about Art brut, which was rendered as an Anglophone equivalent rather than a translation of the notoriously untranslatable French term.34 Contrary to much of the debate that has surrounded it ever since, the word “outsider” is not significantly less protean in meaning than the French word brut; both can function as noun and adjective, and both have multiple referents that nevertheless mostly point away from overcomplication, social control, and gentility. Like all good monsters, the term “outsider art” broke free from the focused reference to Art brut intended by Cardinal and quickly came to stand for a much more expanded field.35

Art brut came into being with, thanks to Dubuffet, a codified taxonomy, which not only described the initial group of artistes-brut but also laid down the checklist for identifying others. Yet Dubuffet also argued—like the early apologists for American folk and self-taught art—that the work spoke for itself; that one instinctively knows Art brut when one sees it. This is one of the paradoxes that lie at the heart of the field. The founding definitions of outsider art provide embryonic form and help explain why certain of its objects and artists are canonical. However, its emotionalist, (anti)aesthetic imperative virtually invites the kind of flux that ought to resist canon formation.

Sela-Sheffy says that “in all canonising processes, the canoniser’s strategies oscillate between the tendency to consolidate an existing canonized repertoire and that of prefiguring a new one and present it as canonical from the outset. Usually, however, the prefiguration of a new canonized repertoire comes only late in the process of canon formation, after a prolonged phase of conformity with the existing canon.”36 In the case of Art brut, Dubuffet’s strategy was clearly that of prefiguring a new repertoire, although it must be emphasized that he was building on a preexisting paradigm established by expressionist and surrealist aesthetics between around 1920 and 1939. Similarly, at the same time in America, people like Barr and Cahill were attempting to create a more broadly inclusive and, in their terms, authentic American cultural canon.37 In the case of outsider art, in its expanded sense, canon formation has followed a more usual pattern: artists are introduced into the discourse and over time enter—sometimes quickly (Martín Ramírez, Dial, George Widener), other times more slowly—the canon, and occasionally slip out of it (Eddie Arning, Lee Godie).

Outsider art is defined less by a repertoire of individual canonical works than by the total production of its canonical figures. Unless we count instances of environments, such as Sabato Rodia’s Watts Towers or Fred Smith’s Wisconsin Concrete Park, which are cumulative and usually constitute a single-work opus, there is no outsider equivalent of Picasso’s Demoiselles d’Avignon, Manet’s Bar at the Folies Bergère, or Pollock’s Blue Poles. There are, rather, the oeuvres of Adolf Wölfli, Bill Traylor, Minnie Evans, Martín Ramírez, and Thornton Dial. All are artists whose work collectively constitutes more than just examples. Their works provide exemplary models, the highest standards by which we might recognize and judge outsider art. They have practices of superior quality against which others are habitually measured; and those quality judgments are generally assumed, without being necessarily articulated in the discourse.

Canon formation is a cumulative process; no Dial without Traylor or Edmondson, for example, but also no canonical Traylor and Edmondson without the continued confirmation of their validity with the appearance of artists like Dial. It is easy today to imagine that Wölfli has always been a canonical figure, yet in spite of being the subject of a full-length monograph by Walther Morgenthaler in 1921, he was not included as one of the “schizophrenic masters” by Hans Prinzhorn in his pioneering book, Artistry of the Mentally Ill, a year later. Neither was he particularly lauded by the surrealists, who preferred the likes of Augustin Lésage and August Natterer. By 1964, though, he was honored to be the sole subject of the second of Dubuffet’s Art brut fascicules (again authored by Morgenthaler). Nowadays, along with Henry Darger and Ramírez, his is one of the few outsider names commonly known by artists and critics unconnected with the field.

If it can be argued that outsider art has canonical figures, it is more difficult to situate them in a continuum that exemplifies the broader paradigm of the field, thereby distancing it in some way from the usual art history canon and its subsets. This is because Wölfli, Ramírez, Dial, and the rest do not readily conform to expectations that they have engaged with and been immersed in a discourse that connects them to previous art or each other. In usual cases, a canonical figure or canonical work is culturally connected to other artists working within the same paradigm. There are arguments, to be sure, that Dial is connected to a shared southern African American vernacular creative culture, and more directly he is part of a small group of artists including Holley and Lockett who share common concerns and know each other well. Yet the direct reach of his influence is negligible, and in art historical terms he remains somewhat unconnected.

“The crucial point about canonicity,” Sela-Sheffy argues, “is the sense of objectification it confers” on families of cultural forms, “thereby naturalizing them in a given socio-cultural order to the point they seem congenital, concealing the struggles that determined them in the first place.”38 This is salient in the case of outsider art, a field that encompasses a number of (still-)competing subsets. While its boundaries remain contested and even its name is still the subject of internal wrangling, there is little doubt that an artistic canon has emerged that is particular to outsider art. Canonical figures have been habitually introduced into debates in the past and sometimes still today as evidence of the legitimacy or otherwise of the field’s familial reach. That such a debate exists is the most tangible confirmation of outsider art’s existence as a field in its own right.

All of this is difficult terrain in a field that has grown in large part out of a series of strategic attempts to sidestep dominant discourses and to valorize marginal practices. Moreover, this is a field that has preached anticanonicity, and to this day has strong anti-intellectual elements. It is also a field that has very often glorified in its own marginality, a kind of inverted snobbishness that not only takes pride in valuing things that the mainstream does not but also guards them from it. Yet even anticanonicity produces canons—if not these sacred objects, then which? The answer is Morris Hirshfield rather than Thomas Hart Benton, Martín Ramírez rather than David Alfaro Siqueiros, Thornton Dial rather than Jasper Johns.

Christopher Nokes has argued that “it is precisely at the borders, boundaries, or frontiers of natural phenomena and human development that we find dramatic change or phase shift,”39 and that this is where canonical figures are likely to emerge, on the grounds that although in inhabiting a paradigm there is more likelihood of artists producing work that accords perfectly with a particular typology, it is in the process of paradigm shift that exemplary models emerge. For example, the work of Monet around 1870, though not yet properly impressionist, is canonical, precisely because it embodies a struggle to create something emphatically new, and offers raw glimpses of impressionism proper. On the other hand, the work of others from later generations working in the full-fledged impressionist idiom could not hope for artistic canonization. This raises an interesting issue in relation to outsider art, where the argument has been, in effect, that it is all phase shift, each and every time, with each and every individual creator. A new paradigm each time, so that potentially all artists enter the canon, or perhaps each artist is their own canon. This said, it has been convincingly argued by a number of writers that artists like Dial have inhabited precisely a moment of paradigm shift. McWillie, for instance, appears to be making a direct argument for the canonical status of Dial and one of his works, The Coal Mine (1989), when she writes: “Both the artist and the painting are emblematic of a generation of working-class African Americans who grew up in the South during the era of segregation and lived to witness and participate in the social transformations of the American Civil Rights movement.”40 He is, then, from an art historical point of view, difficult to locate. And such searching after connections and art-familial relations is the art historian’s default position. Jane Livingston is typical in trying to locate Dial within the prevailing paradigm but concluding that “he simply doesn’t conform to any of our categories or expectations.”41 The “us” of this statement is a metropolitan, highly educated, (white) middle-class audience far removed from Dial’s own experience. Little wonder, then, that she concludes: “Try as we might to relate Dial to other artistic traditions, we cannot easily do it.”42

If Dial’s practice can be characterized as broadly expressionist, though, his introduction to the New York art world in 1993 was doubly unfortunate, coming immediately after the end of the ascendency of so-called neo-expressionism, and in the wake of a concerted critical attack on its tenets. Craig Owens, for example, recognized the legitimacy of what he saw as the sincere, if utopian, project of early expressionism: “Expressionism was an attack on convention (this is what characterizes it as a modernist movement), specifically, on those conventions which subject unconscious impulses to the laws of form and thereby rationalize them, transform them into images. . . . The Expressionists, however, abandoned the simulation of emotion in favor of its seismographic registration.” But he rejected its supposed reemergence in 1980s new art, accusing neo-expressionism, on the contrary, of being “Expressionism . . . reduced to convention.”43 Hal Foster, another highly influential critic, was equally scathing: “Neo-Expressionism: the very term signals that Expressionism is a ‘gestuary’ or largely self-aware act.”44 On one hand, Foster rightly pointed to the “rhetorical nature” of expressionism and its “status as a language,” in the face of claims to the contrary by expressionist artists and critics: “Expressionism is a paradox: a type of representation that asserts presence—of the artist, of the real. Of course, this Expressionist presence is by proxy only.”45 On the other hand, the materialism underpinning Foster’s worldview does not allow for idealism or metaphysics. “Neo-Expressionism,” he says, “occurs as one more belated attempt to recenter the self in art,” in spite of revelations that “subjectivity has proven to be no more exempt from reification and fragmentation than objective reality.”46 Such critique presupposes highly self-aware practices, conducted at least as much with an eye to historical precedence as to the immediate demands of visual communication. Though this might be true of neo-expressionist painters like Julian Schnabel or Sandro Chia, it is hardly the case for Dial, who argues strongly that his is a considered practice, though one that has developed directly from accumulated experience: “It seem like some people believe that just because I ain’t got no education, say I must be too ignorant for art. Seem like some people always going to value the Negro that way. I believe I have proved that my art is about ideas, and about life, and the experience of the world. I have tried to learn how to explain everything I did. I tried to name everything that could be named about that experience, and if a person still see ignorance in me, he might just be looking into his own self.”47

By virtue, then, of little more than a certain, coincidental visual resemblance, Dial’s work was thus indirectly, but no less damagingly, implicated in a debate that rejected expressionism’s putative late manifestation as pseudo-expressionist, trading on “the quotation of modernist conventions.”48 Similarly, Dial’s treatment of historical narrative, through means that are highly personal and at times idiosyncratic invoked spirit clash with an art world moment in which the “death of history” was a buzz phrase. As Foster said, “Far from a return to history (as is so ideologically posed), recent culture attests to an extraordinary loss of history—or rather a displacement of it by the pseudo-historical.” Artists, in general, he argued, “only seem to prize open history . . . in fact, they give us hallucinations of the historical, masks of these moments. In short, they return to us our most cherished forms—as kitsch.” At best, the appearance of neo-expressionism is a “problematic response” to the loss “of the historical, the real, and of the subject.”49 Where, then, does Dial fit in all this? On the contrary, he senses no loss of history; instead, part of his project is a reclaiming of history: “My art is talking about the power. It is talking about the coal mines and the ore mines and the steel mills. It is talking about the government, and the unions, and the people that controls the hills and the mountains. The power of the United States is the fuel that carries the United States on. It carries everything, the mills and factories and stores and houses. I try to show how the Negroes have worked in all these different places and have come to help make the power of the United States what it is today.”50

At the height of the First World War in 1916, Hermann Bahr wrote: “This is the vital point—that man should find himself again. . . . He has become the tool of his own work, and he has no more sense, since he serves the machine. It has stolen him away from his soul. And now the soul demands his return. This is the vital point. All that we experience is the strenuous battle between the soul and the machine for the possession of man. We no longer live, we are lived.”51 Art—and specifically a metaphysical expressionist art—was to be the means by which this restoration might be effected. In Foster’s view, such ideas cannot be legitimately applied to the contemporary, for, he says, “However real alienation is today, the crisis of the individual versus society is largely a cliché, as is the crisis of high versus low culture.” This is a highly privileged view of the cultural moment, arguably representative as much of Foster’s intellectual milieu and Manhattan-dominated worldview as of any general truth. Perhaps unsurprisingly, it jars somewhat when we attend to Thornton Dial. Without knowing of either Foster or Bahr, after first acknowledging the unfortunate history of racial inequality and struggle in the United States, Dial adopts a characteristically optimistic view: “I don’t believe there is any natural hate in people. I believe there is natural love. We can relate to people’s spirit and we can relate to their mind. I understand those things, and I believe we need to make the mind more close to the spirit.”52 And for him, like Bahr, art can be the agent of change: “Art is like a bright star up ahead in the darkness of the world. It can lead peoples through the darkness. Art is a guide for every person who is looking for something. That’s how I can describe myself. Mr. Dial is a man looking for something.”53

NOTES

1 Henri Matisse, “Notes of a Painter,” in Art in Theory 1900–1990, ed. Charles Harrison and Paul Wood (Oxford: Blackwell, 1992), 73.

2 Thornton Dial, “Mr. Dial Is a Man Looking for Something,” in Souls Grown Deep: African American Vernacular Art of the South, vol. 2 (Atlanta: Tinwood Books, in association with the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture and The New York Public Library, 2001), 202.

3 Matisse, “Notes of a Painter,” 72.

4 Dial, “Mr. Dial Is a Man Looking for Something,” 202.

5 Ibid., 221.

6 Ibid., 201–2.

7 Ibid., 202.

8 Ibid., 208.

9 Ibid., 201.

10 Clement Greenberg, “‘American-Type’ Painting,” in Modern Art and Modernism: A Critical Anthology, ed. Francis Frascina and Charles Harrison (London: Harper and Row, 1982), 94.

11 Dial, “Mr. Dial Is a Man Looking for Something,” 221.

12 Examples include Outside the Mainstream: Folk Art of Our Time (Georgia-Pacific Center, High Museum of Art, Atlanta, 1988); Outsider USA (Malmo Konsthall, Sweden, 1991); Living Traditions: Southern Black Folk Art (Museum of York County, South Carolina, 1991); and Black History and Artistry, Work by Self-Taught Painters and Sculptors from the Blanchard-Hill Collection (Sidney Mishkin Gallery, New York, 1993).

13 Notably, the Ricco/Maresca and Luise Ross Gallery, both New York City.

14 Thornton Dial in the 21st Century, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, September 25, 2005–January 8, 2006; and Hard Truths: The Art of Thornton Dial, Indianapolis Museum of Art, February 15–May 15, 2011.

15 “Tinwood’s History,” www.tinwoodmedia.com/Tinwood-Who-We-Are.html, accessed January 7, 2011.

16 See, for example, Holger Cahill, American Folk Sculpture (Newark, N.J.: The Newark Museum, 1931); the exhibitions organized at New York’s Museum of Modern Art by Cahill and Janis, respectively, Masters of Popular Painting (1938) and Contemporary Unknown American Painters (1939); and Sidney Janis, They Taught Themselves: American Primitive Painters of the 20th Century (New York: Dial Press, 1942).

17 For a critical introduction to the changes in terminology in the American context, see, for example, Charles Russell, “Finding a Place for the Self-Taught in the Art World(s),” in Self-Taught Art: The Culture and Aesthetics of American Vernacular Art, ed. Charles Russell (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2001), 3–34.

18 Judith McWillie, introduction to Another Face of the Diamond: Pathways Through the Black Atlantic South, exhibition catalog (Atlanta, Ga.: New Visions of Contemporary Art Gallery, 1989), 7.

19 William Swislow, “Catching All, Capturing Little,” Interesting Ideas, www.interestingideas.com/out/testim.htm, accessed January 4, 2011.

20 Jerry Cullum, “Vernacular Art in the Age of Globalization: A First Few Random Notes,” Art Papers 22, no. 1 (January–February 1998): 11.

21 Tessa DeCarlo, “In Defense of ‘Outsider’: A Question of Labels,” New York Times, January 13, 2002, section 2, 35.

22 Swislow, “Catching All, Capturing Little.”

23 The most complete description of these activities remains Lucienne Peiry, Art Brut: The Origins of Outsider Art (Paris: Flammarion, 2001).

24 Dubuffet defined the term Art brut in an article published in English as Jean Dubuffet, “Art Brut in Preference to the Cultural Arts,” in Art Brut: Madness and Marginalia. Art & Text, ed. A. Weiss, Special Issue, no. 27 (December-February, 1988): 30–33.

25 See Colin Rhodes, “Les fantômes qui nous hantent: en écrivant Art brut et Art Outsider,” Ligeia: Dossiers sur l’art, nos. 53, 54, 55, 56 (July–December 2004): 183–95.

26 Thomas McEvilley, afterword to Thornton Dial in the 21st Century, ed. Paul Arnett, Joanne Cubbs, and Eugene W. Metcalf Jr. (Atlanta: Tinwood Books, in association with The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 2005), 314.

27 Amiri Baraka, “Revolutionary Traditional Art from the Cultural Commonwealth of Afro-Alabama,” in Arnett, Cubbs, and Metcalf, eds., Thornton Dial in the 21st Century, 174.

28 Christopher B. Steiner, “Can the Canon Burst?—Art—Rethinking the Canon,” Art Bulletin 78 (June 1996): 214.

29 Ibid.

30 Steve Edwards, introduction to Art and Its Histories: A Reader, ed. Steve Edwards (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999), 4.

31 Steiner, “Can the Canon Burst?,” 213.

32 Rakefet Sela-Sheffy, “Canon Formation Revisited: Canon and Cultural Production,” Neohelicon, no. 2 (2002): 141. Also: “We cannot ignore the fact that there is always a more solid body of artefacts and patterns of action which enjoy larger consensus across society, and persist for longer periods, even in cases where specific contemporary ideologies tend to reject them” (ibid., 145).

33 See, for example, Judith McWillie, “African-American Vernacular Art and Contemporary Practice,” in Testimony: Vernacular Art from the African American South: The Ronald and June Shelp Collection, ed. Anne Hoy (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., in association with Exhibitions International and the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, 2001).

34 Roger Cardinal, Outsider Art (London: Studio Vista, 1972). Cardinal has always been keen to point out that “outsider art” was conceived as an English-language equivalent of Art brut and that his “book dealt directly and explicitly with Art Brut, which is the term used throughout the text” (Roger Cardinal, “An Intercontinental Perspective,” in Art Outsider et Folk Art des collections de Chicago, ed. L. Danchin and M. Lusardy [Paris: Halle Saint Pierre, 1998], 18).

35 Cardinal himself notes that “there is no doubt that what we have been calling ‘Art Brut’ or ‘Outsider Art’ has been in a state of flux since the very beginning, and that we are today faced with a crisis of definition produced by two things: the thoughtless manipulation of the instruments of definition that has compromised their accuracy and the sheer proliferation of discoveries over the past few years” (Cardinal, “Intercontinental Perspective,” 21). Cardinal himself, however, has been complicit in this process, arguably from the outset, when he included a number artists in his book not originally considered Art brut but who he thought fitted Dubuffet’s criteria and worthy of inclusion.

36 Sela-Sheffy, “Canon Formation Revisited,” 142.

37 It is interesting that at the beginning of this century, Thomas McEvilley noted the modernist recognition that, “unlike the art of the so-called African primitive, the art of the African American is a domestic product” but read its impact not so much as formative of a broader, peculiarly American tradition as “a homegrown challenge to white hegemony in the arenas of both culture and politics” (McEvilley, afterword, 312).

38 Sela-Sheffy, “Canon Formation Revisited,” 146.

39 Christopher Nokes, “A Global Art System: An Exploration of Current Literature on Visual Culture, and a Glimpse at the Universal Promethean Principle— with Unintended Oedipal Consequences,” Journal of Aesthetic Education 40, no. 3 (2006): 97.

40 McWillie, “African-American Vernacular Art,” 11.

41 Jane Livingston, “An Artist in the Twenty-First Century,” in Arnett, Cubbs, and Metcalf, eds., Thornton Dial in the 21st Century, 300.

42 Ibid.

43 Craig Owens, “Honor, Power and the Love of Women,” Art in America 71, no. 1 (January 1983): 9.

44 Hal Foster, “The Expressive Fallacy,” Art in America 71, no. 1 (January 1983): 80.

45 Ibid.

46 Ibid., 83.

47 Dial, “Mr. Dial Is a Man Looking for Something,” 217, 220.

48 Owens, “Honor, Power and the Love of Women,” 11.

49 Foster, “Expressive Fallacy,” 137.

50 Dial, “Mr. Dial Is a Man Looking for Something,” 200.

51 Hermann Bahr, “Expressionism,” in Frascina and Harrison, eds., Modern Art and Modernism, 168.

52 Dial, “Mr. Dial Is a Man Looking for Something,” 198.

53 Ibid., 221.

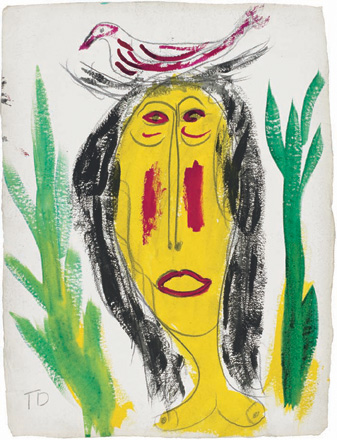

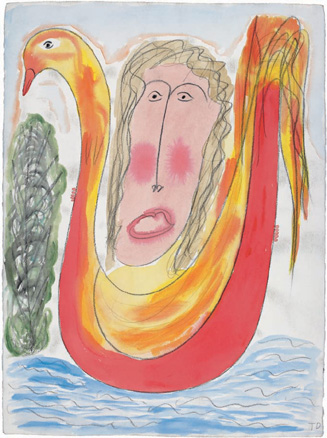

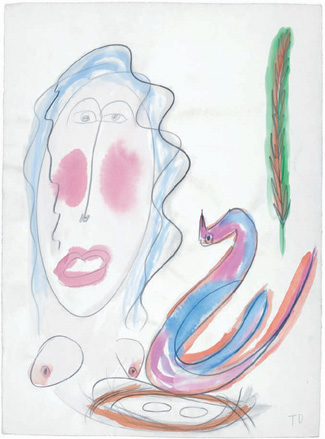

Plate 17

Life Go On, 1990

watercolor

30 ½ × 23 ¼ in. (77.5 × 59.1 cm)

Courtesy of the artist and The Souls Grown Deep Foundation

L2010.22.28

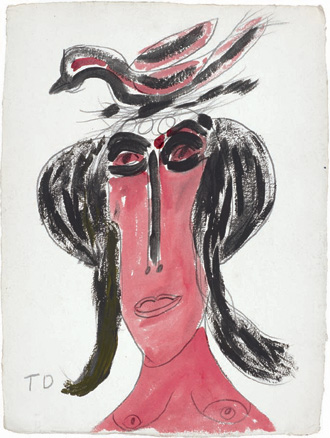

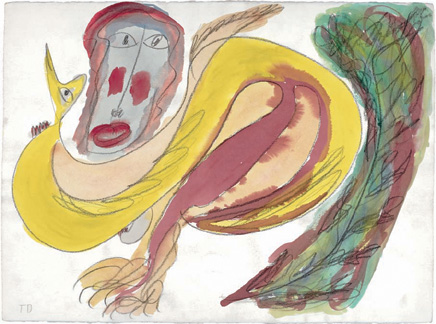

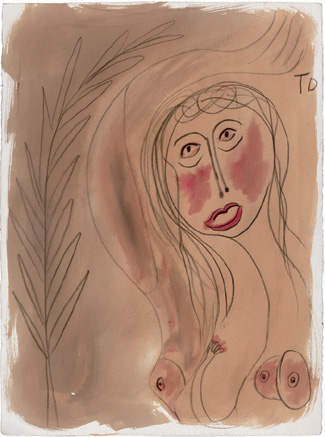

Plate 18

Life Go On, 1990

watercolor

30 ½ × 22 ½ in. (77.5 × 57.2 cm)

Courtesy of Mr. Tom L. Larkin

L2010.20.8

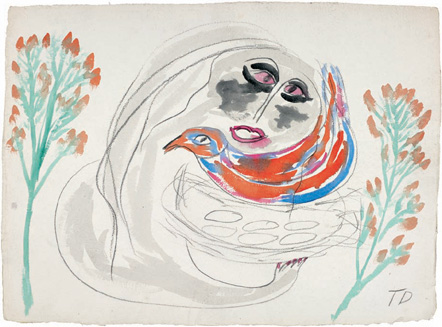

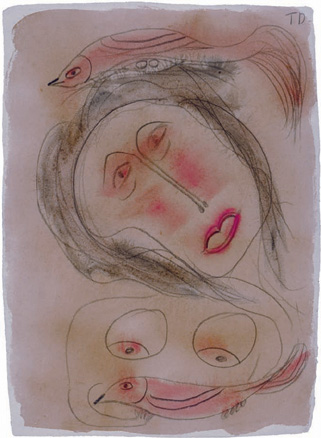

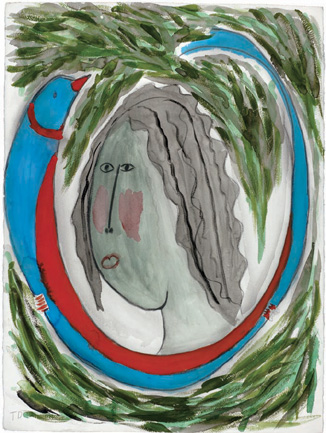

Plate 19

Lady Holds the Peace Bird, 1990

watercolor

22 ⅛ × 30 ⅛ in. (56.2 × 76.5 cm)

Courtesy of Mr. Tom L. Larkin

L2010.20.10

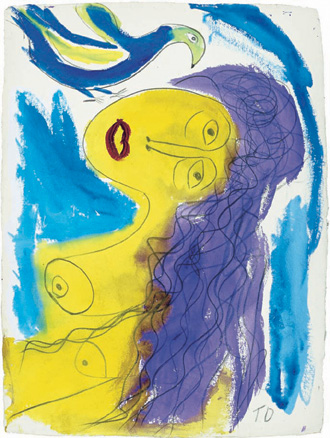

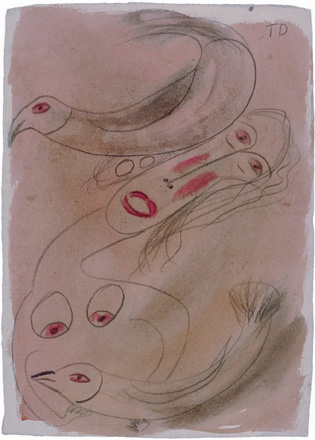

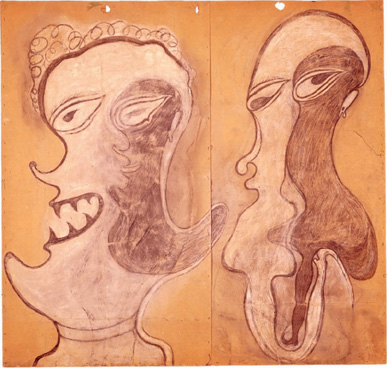

Plate 20

Lady Watches the Freedom Bird, 1990

watercolor

30 ½ × 23 in. (77.5 × 58.4 cm)

Courtesy of the artist and The Souls Grown Deep Foundation

L2010.22.29

Plate 21

Long Neck Goose, 1991

watercolor

29  × 22 ⅛ in. (75.7 × 56.2 cm)

× 22 ⅛ in. (75.7 × 56.2 cm)

Courtesy of the artist and The Souls Grown Deep Foundation

L2010.22.23

Plate 22

A Lady Will Hold a Strange Bird

watercolor

22 ¼ × 29  in. (56.5 × 75.7 cm)

in. (56.5 × 75.7 cm)

Courtesy of the artist and The Souls Grown Deep Foundation

L2010.22.3

Plate 23

Life Go On, 1990

watercolor

30 ⅛ × 21 ⅛ in. (76.5 × 53.7 cm)

Courtesy of the artist and The Souls Grown Deep Foundation

L2010.22.2

Plate 24

Life Go On, 1990

watercolor

30 × 22 ¾ in. (76.2 × 57.8 cm)

Courtesy of the artist and The Souls Grown Deep Foundation

L2010.22.27

Plate 25

Lady Holds On to the Love Bird, 1991

watercolor

30  × 22 ⅛ in. (77.3 × 56.2 cm)

× 22 ⅛ in. (77.3 × 56.2 cm)

Courtesy of the artist and The Souls Grown Deep Foundation

L2010.22.26

Plate 26

Life Go On, 1990

watercolor

22 ¼ × 29  in. (56.5 × 76.0 cm)

in. (56.5 × 76.0 cm)

Courtesy of the artist and The Souls Grown Deep Foundation

L2010.22.22

Plate 27

Life Go On, 1991

watercolor

22 ¼ × 30 in. (56.5 × 76.2 cm)

Courtesy of the artist and The Souls Grown Deep Foundation

L2010.22.21

Plate 28

Life Go On in the Woods, 1991

watercolor

29  × 21 ⅞ in. (76.0 × 55.6 cm)

× 21 ⅞ in. (76.0 × 55.6 cm)

Courtesy of the artist and The Souls Grown Deep Foundation

L2010.22.20

Plate 29

Lady Holds the Long Neck Bird, 1991

watercolor

30 × 21 ¾ in. (76.2 × 55.25 cm)

Ackland Art Museum, Gift of The Souls Grown Deep Foundation

2011.15.6

Plate 30

Up and Down, 1991

watercolor

29 ¾ × 22 ⅜ in. (75.6 × 56.8 cm)

Courtesy of the artist and The Souls Grown Deep Foundation

L2010.22.17

Plate 31

Life Go On, 1991

watercolor

29 ⅛ × 22 ⅛ in. (74.0 × 56.2 cm)

Courtesy of Martha Howard Collection

L2010.21.4

Plate 32

Lady with a Pink Bird, 1991

watercolor

30 × 22 ½ in. (76.2 × 57.2 cm)

Courtesy of Martha Howard Collection

L2010.21.3

Plate 33

Life Bird, 1990

watercolor

29 ¾ × 22 in. (75.6 × 55.9 cm)

Courtesy of Mr. Tom L. Larkin

L2010.20.3

Plate 34

Picture Frame—Life Go On

watercolor

30 × 22 ⅜ in. (76.2 × 56.8 cm)

Courtesy of Mr. Tom L. Larkin

L2010.20.5