We All Grew Up in That Life

Thornton Dial’s Sexual Politics on Paper

Thornton Dial’s works on paper raise difficult questions concerning categorization and power. What is at stake is nothing less than how Dial and his art should be positioned in mainstream contemporary American art. Labels applied to Dial, like self-taught, outsider, and even African American, are the artifacts of a particular kind of political power. Dial may be all of the things these labels suggest—an outsider to the art world, an African American, and self-taught (if that means he did not attend a certified art academy or study under the tutelage of an insider artist)—but he is much more. These deeply marginalizing modifiers have been used to describe his art and his life for decades. But how can Dial and other artists break free of politically convenient labels when the very system that brings their work to broader audiences engages these terms for their own purposes? Early in Dial’s artistic career a New York City gallery hosted a show of his work.1 The graphics for the show used a photograph of the artist standing in front of his tin-roofed work shed and studio. That single image in that metropolitan venue far from central Alabama served the gallerists well. Without providing a caption that contextualized the photograph, they successfully introduced Dial in a manner that defined and limited the reception of his art. Dial, it is said, was not invited to the opening because exposure to the gallery world and the city would have “tainted” him and his art. It is an established and invidious tradition that would relegate Dial to such a position. How often does the “art world” do this to artists? And why?

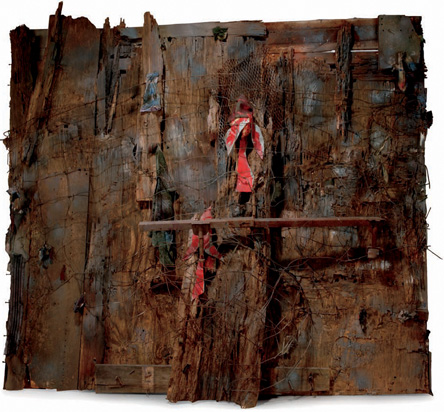

Figure 4.1 Thornton Dial, Graveyard Traveler/Selma Bridge (1992). Rope carpet, burlap, tin, wood, wire, plastic bagging, paint-can lids, pine cones, carpet, plastic hose, wire screen, rope, found metal, oil, enamel, and Splash Zone compound on canvas on wood. 85 ½ × 148 × 6 inches. Courtesy of the artist and The Souls Grown Deep Foundation.

I know, as a working artist, that I live in this country day in and day out and am labeled an African American artist. I also know that whenever I leave the country, I become an American artist. Period. True for me. True for Dial. Dial is an artist. Period. Only when he is presented this way, and not as a self-taught outsider, only when he is spoken of as an American artist—not confined to the role of African American artist—do I begin to more richly understand the power and complex beauty of his drawings.

In the early 1990s, Dial began using paper in response to a negative review that spoke of him as a folk artist of limited aesthetic sensibility and ability. An interview on the television show 60 Minutes in 1993 presented Dial as something of an uneducated savant whose art lacked the sophistication of an academically trained artist. Before the interview, Dial was an artist on the rise in the art world; after, even though his fortunes faltered, his commitment to artistic expression and experimentation did not. Dial began creating new and dynamic works on paper. These new images explored themes and concerns not easily recognized in his larger works. In fact, the drawings suggest that a vital tension exists between the marginalizing language expressed in the art critical media and the artist. These drawings add new layers of challenge to labels like “folk” and “outsider” and render them hugely problematic in very real political terms.

Thornton Dial’s monumental mixed-media sculpture and paintings continue to shape our reception of his art almost to the exclusion of his engagement with other media. For the majority of people familiar with his work, and for me as an artist, it is his towering, always tactile assemblages that stand as definitively Dial. For example, richly layered and visibly deliberate in its construction, Graveyard Traveler/Selma Bridge (1992) (fig. 4.1) illustrates the scope and complexity of Dial’s larger work—some requiring five years to complete—and how they embody a sustained process of reflection. Even as Graveyard Traveler directly addresses and records the specific historical moment in 1965 of Bloody Sunday on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, it also speaks to the course of every life. The sculpture reminds me, I am a graveyard traveler from the day of birth onward.

Dial’s drawings have the same impact. While the drawings are typically placed in a subordinate position in discussions of his art, turning attention to his early mixed-media compositions on the figure of the tiger or, more recently, to provocative political commentaries such as Everybody’s Welcome in Peckerwood City (2005) (figs. 4.2a and 4.2b), Dial’s drawings explore, and offer variations on, a number of complementary themes. As an artist, I experience the tangible, physical presence associated with Dial’s large pieces—richly layered works composed of found objects, paint, metal, and wood that possess have a vital relationship to the immediacy of works on paper. There are two different but parallel processes at work, with each process revealing aspects of the artist himself.

In the drawings, Dial tends to put his ideas down on the paper and then walk away, only occasionally returning to highlight or add elements to the work. Because the drawings are not worked and then reworked, they afford the artist a particular opportunity for developing new ideas, giving the artist the ability to “play” with ideas, faster, more easily, and more freely. In the drawings, the artist discovers quickly what will work and as a result might resolve conceptual issues embedded in or related to a larger work. The big, deliberate works are almost archaeological, built up in strata, layer upon layer,

Figure 4.2 a and b Thornton Dial, Everybody’s Welcome in Peckerwood City (2005), two views. Doormat, cardboard, wood doors, steel, tin, bed frame, wire fencing, wood, towel, enamel, and spray paint. 81 ½ × 93 ½ × 33 ½ inches. Courtesy of the artist and The Souls Grown Deep Foundation.

but in the drawings, surface and spontaneity prevail. In the drawings, Dial is thinking on paper, recording perhaps random and intermittent thoughts while visualizing his understanding of possible relationships between the sexes. While themes and symbols repeat over and over again—the tiger, women, fish, and life’s eternal circle—he is not working in a series. These symbols appear in many of his works, including the big sculptures, where they are presented in ways that are literally more layered and as a result typically more nuanced. By contrast, in the works on paper, these same images appear directly, spontaneously, and with a unique presence and power.

The new medium is a fresh development in his artistic process, and he experiments with it, trying a variety of papers, watercolors, pencils, charcoals, and crayons. The flatness seen in these first works on paper suggests that Dial made these images very quickly, while the larger sculptures and paintings are constructed in layers, built from the inside out with time to play with, manipulate, and develop ideas. The early drawings are quick, complete works, fully executed in a single session and only occasionally revisited. Quite beautiful in their own right, these are gestural studies of relationships and power, explored within the symbols of the tiger and the woman, the bird and the fish. His bold and economical handling of line makes the energy of the tiger and the solidity of the woman visible.

Dial uses color and line to speak to the power he associates with the tiger: the fitness, the leanness, and the strength. The muscularity of the body seen in a drawing like Some Tigers Coming, Some Going (Some Look Ahead Some Look Back) (ca. 1990) (plate 15) depends on a confidence of line. The muscled body and the direct gaze make it clear that there is no backing down. Through the persona of the tiger, Dial challenges the intruder: “You don’t want to come this way.” And, again, in works like Life Go On with the Tiger (1990) (plate 16) and Lady with Her Tiger—Life Go On (1990) (plate 14), Dial’s tiger dominates and engulfs the woman. Similarly, it is the heaviness of his line in Ladies Stand by the Tiger (1991) (plate 10) that shapes our perception of the tiger in all its fierce virility. The lines describe a tiger that is aggressive and alert, with its bristled back in a posture that could reflect the instant before attack or a warning against an intrusion into a protected personal space. The line is strong, but it is also refined—with the sensibility of Dial’s confidence and resolve. The tiger is comfortable with himself—and this is central to who the tiger/Dial is, how we see him, and most of all how he sees himself.

Dial presents the tiger as fit and slim and constantly in motion; he renders women as bare-breasted, typically rouged, and static. Still considering Ladies Stand by the Tiger, which was executed in water-color, graphite, and black wax crayon, Dial positions the tiger at the center of the composition. The big cat’s body presses two women to the edge of the page. A third woman reclines, embraced in the oval formed by the tiger’s tail, back, and ear. Key to this drawing is the depiction of the tiger as a large, muscular, and assertively masculine presence. He is sleek, streamlined, and trim—much like the artist himself. His arched back and extended claws communicate watchfulness and ferocity. The women exist within his sphere of power and protection.

Dial has been questioned about the sexual frisson in this drawing and its companions, and his answers are revealing. “You know it’s all about love,” Dial begins, but then he complicates his answer, blurring the lines, pressing a simple answer to the edges: “Well, sure. You can’t get along without a woman. So you go out and hang out and have a good time.” He speaks to the tiger on the prowl and reconciles its libidinous extramural pursuits to the relationship between man and wife: “Your wife just has to understand.”2 Dial speaks through the tiger: men are alive, empowered, and on the move. The women in this, as in other drawings, are an open-ended conflation of women as girlfriends and wives, as keepers of sexuality and spirituality, and as agents of license and restraint.

But the images also support an examination of trends. For example, Dial’s tigers are constantly in motion and often, if not always, in power. In Some Tigers Coming, Some Going, Dial captures the energy of the twisting cat at the center of the composition and the constrained placement of the woman between the tiger’s legs. The two tigers in the drawing are actually a single animated figure. Dial deploys this device—using multiple figures to convey the agitation and excitement of a single figure in motion—in many of his drawings. The faces on the tigers capture both the distracted delight of the moment and the watchfulness that is the cat’s constant preoccupation. Even though in command, the tiger remains acutely aware of his surroundings and the possibility of the invasion of his space.

In contrast to the fully developed tiger in this work, the woman is constructed of face, breast, and a single arm wrapped around her partner’s leg. Dial’s representations of women consistently emphasize breasts as spheres that float in relationship to the body. He uses this disembodied quality, making the breasts as though they were detachable erotica, to suggest that the viewer can have them, pick them up and take them away. I can almost hear Dial thinking, “Damn, that looks good,” as he separates the breasts from the complete person. It is a dynamic and a dangerous move, a very different treatment from what he gives to his tiger. Dial is consistent in his treatment of women and equally so with the tiger, particularly when the tiger is in the presence of a woman or women. He reduces the body of the woman in Some Tigers Coming, Some Going to those elements central to her actions. Like actors enveloping each other on the paper, they look outward at the viewer and not at each other.

In Sitting in the Shade (1990) (plate 11) Dial speaks eloquently about the fun of being a man, of being the tiger, of hanging out in juke joints on Friday and Saturday nights. But Sitting in the Shade is a complex drawing that speaks to much more than a momentary dalliance. Notice how he positions the woman next to a tree with her legs apart and her hands clasping the forelegs of the tiger above and around her. The drawing interrupts an erotic interlude, and the tiger and the woman look directly at the viewer, once again, inviting multiple interpretations of their relationship. The tiger and the woman are positioned in a way that strongly suggests mutuality, the giving and receiving of sexual pleasure. The woman’s heavily rouged cheeks and intensely red lipsticked mouth coupled with the tiger’s sleek form and luxuriously whiskered face evokes associations of dressing up and stepping out on a Saturday night. Both the tiger and the woman are in a moment that is, on an immediate level, about sexual love and on another about a kind of freedom. In this sense, woman and tiger are on equal standing. But something else is happening here. Dial seats the woman in the shade; she is in the tiger’s shadow. Pleasure, it appears, may be mutual, but power is not.

On first viewing, Dial’s women appear to lack individual qualities from drawing to drawing, but this is not what I see when I look again. The female figures in Sitting in the Shade, Some Tigers Coming, Some Going, and, indeed, all the drawings represent both “woman” as type and “this woman” as a unique individual. Just as the tiger is at once Dial and southern African American men in general, so too are the women themselves and all. Dial explains, “People say I make all my art about tigers, but I got tigers in just some of it. Women be in just about everything I have made, in one way or another way. That tiger for me symbolized the struggle, in the works of life. If it wasn’t for women it wouldn’t be none of us here, and without them we couldn’t make it through the struggle. Man do a lot of struggling— that’s true—but without women giving the power and the strength of their struggle to man’s struggle, man going to lose his struggle.”3 Dial talks candidly about the women who have shaped and inspired him, including his wife, great-grandmother, mother, and aunt, but he simultaneously separates and conflates spiritual and physical love: “Some of them are [about] love, but not sex-love,” he explains. “You understand that? Well, that’s the way I draw pictures. I love my mama, and I love my wife. So we don’t have to separate that stuff.”4

Tiger Will Stand by This Lady, As Life Go On (plate 9) is another example of these representations of masculine and feminine relationships and power in Dial’s early tiger drawings. The tiger is in charge of both the composition and the situation. There is no reason to question his authority; the tiger possesses the power. The tiger is sinuously complete and fluid. Presented without the rouge and makeup, the woman’s body is reduced to a collection of suggestive parts, consisting only of a segmented head, arm, and breast, a constellation of body parts revolving, existing solely in the orbit of the tiger. The bird perched to the side of the intertwined figures suggests the woman’s other self as nurturer, not the lover. Dial reinforces this aspect of the woman, and this essential role, by including a nest filled with eggs cradled in the arc of the tiger’s upper rear leg. The woman may be located at the center of the drawing, but this is all about the tiger as possessor and protector of the feminine body and all its associations.

Dial addresses this theme again in Laying Down with the Tiger (1991) (plate 2). The woman lies under the tiger, and the tiger controls the situation. But in this drawing, Dial literally draws attention to the power of women. He situates the woman in a position where she may appear to lack power—in fact, viewers of this work often see her as vulnerable in the company of a dominant male—but Dial claims that he is representing women in the context of wanting them to achieve and be uplifted. If these are pictures of sexual politics, as some have suggested, then I ask, whose politics? Is the woman safe and open? Is she uplifted? Is the tiger quite secure?

In spite of the dominant position of power Dial bestows upon the tiger in Laying Down with the Tiger and other drawings like People Will Watch the Struggling Tiger (1991) (plate 7) or Lady Will Stand by Their Tigers (1990) (plate 6), something suggests that the tiger is also vulnerable to forces outside the image. The tiger is startled by a presence that looks into his realm—an unseen but implicitly and insistently disruptive power. This interpretation carries a certain validity, especially when placed within debates about the pernicious presence of “whiteness” as a construction of power that reveals itself only through its “other.” Is Dial portraying the tiger as startled and insecure because of the racial history of the South or because of the marginalizing commentary on Dial’s art? Because of the events and experiences that shaped Dial’s life or because of the commentary this life receives?

Dial never learned to read and write. He started working at a very young age, working really hard. From the skills he learned on the job, he began to make objects. He buried or recycled his very early sculptural works because he feared reprisals from the white community for his criticisms of social norms.5 But it is important to remember: his experiences bred in him certain attributes that prevented his constant assertion of power. Simply, the watchfulness represented in Dial’s drawings is not necessarily weakness, and wariness is not necessarily insecurity. Beginning as children, working for whites— and always in a subordinate role—African American men, including Dial, had to ask for certain kinds of things, and the necessity of “asking,” of making these requests, bred a culture of insecurity, anger, and resistance among them. Dial and other African American men of his generation with similar backgrounds were usually not operating from a position of power, and often did not have the ability to empower themselves, at least not openly. The jobs were not their jobs. Just as they were given, they could just as easily be taken away. I believe this situation/position, a subordinate one, and often with racial overtones, bred a culture of insecurity and anger. But this is not to say that these men did not work in subversive ways to counter how they were made to feel. Their image as it related to other African American men, but especially as it related to women, was paramount. The tiger is never weak. And of course, it has long been said and must be understood that “grinning is not always grinning.” Dial knows, as do I, that we survive as a race because of African American women and their strength, even if that is not the dynamic represented in his early drawings of women and tigers. While I can talk about insecurity, I never see the tiger in a very insecure environment. That picture space and all that it signifies is the tiger’s own. In attitude and posture, the tiger communicates his authority in that world. Dial’s tiger is always in charge, as surely as Dial himself, as an artist, is always in charge.

Dial’s early drawings depict different realities and different agendas that exist for men and women, and, when asked, Dial speaks pointedly to these separate spheres: “You have your role, I have my role, and this is what it is.” In Dial’s drawings, women are not only sexual beings, their rouge, lipstick, and makeup highlighting a kind of erotic availability; they are also wellsprings of love, strength, care, and power, as the physical creators of the world of his drawings.

But other figures join the company of the tiger and the women in these early works on paper. Bright red fish appear in his Fishing for Love pieces, serving as complex signifiers for a woman’s allure. Men of a certain generation, for example my father, talked about women in a particular way: the specifically erotic scent of women was associated with fish. When Dial speaks of “fishing for love,” he is referring to seduction. In one sense, the women present the fish as enticements for masculine passions in drawings like Ladies Hold the Fish for Love (1991) (plate 44), Fishing for Love (1991) (plate 41), or Fishing for Love (1990) (plate 40). They function as lures cast to capture men looking for love. Dial’s representations of fish in other drawings are invariably associated with women—but the implications are not always the same. Unlike in the drawings mentioned above, in Fishing for Love (1991) and other works like it, Dial suggests the women are not only luring the men, they are holding the fish as trophies. The women are the ones doing the looking. On one hand, the fish refer to wiles and allures of women; on the other they stand as emblematic reminders of the woman’s success, of her ultimate conquest.

Even as Dial delineates women fishing for affection, he implicitly refers back to the persona of the tiger. A curious element in the Fishing for Love series is that the tiger—representing Dial or other African American men—may also be read as having nothing to do with “looking for love” but only, and always, ready to take advantage of the moment. It is as though men find themselves surrounded by the possibility of love and responsive to its availability. The tiger is never looking for love but usually finds himself surrounded by the possibility of love and is usually responsive to its availability. While the tiger may not be literally present in the Fishing for Love series, the love that Dial is referring to is the love of the man/tiger. This reading suggests or refers to an inherent tension within the artist. He wants to elevate women even as he keeps them within the orbit of the tiger’s passions.

As a consequence of this tension, no one can be confident in the love Dial’s women offer. There are too many unanswered questions about the uses of allegory, memory, and intention in these works. I can locate Dial’s drawings within his own autobiography and place them in a larger historical experience of men forcibly removed from family or of men choosing not to stay. To what extent do these drawings, like those in the Fishing for Love series, represent the wants, needs, and desires of men and women at a particular time and in particular circumstances? Are they satisfied? Are they left unfulfilled?

In so many of Dial’s early drawing, the tigers are pictured with more than one woman, and the women are pictured with more than one fish. I think back to my experiences in juke joints “back in the day.” These drawings resonate with and celebrate the license and liberty of those Friday or Saturday nights. The women in Dial’s drawings are fully sexualized beings enthralled with their tigers, and equally free and on the prowl. But, as Dial suggests in other works, for example Life Go On (1990) (plate 17), no matter how made-up and sexually available these women may be on some occasions, invariably they have other concerns—family, children, domestic stability. Dial presents this complexity, speaking to the power women hold within the eternal cycle of life. They may be lovers, but they are also mothers and wives, the final protectors of family and home.

It is significant that Dial represents the tiger as susceptible only to women and never vulnerable to other tigers. In Life Go On (plate 17), Dial uses color to make this point. The drawing is a clear visual demonstration of female power. There is nothing weak about this woman. Her bright red–daubed cheeks lend her the air of a warrior. There is a power in this drawing. The bird’s nest on her head lets me know what she is thinking, and if I imagine she is speaking, I hear her say, “Yeah, this is my place. Don’t mess with me here. Don’t come here. I don’t play.” She is guarding her nest. Even in the more idyllic Lady Holds the Peace Bird (1990) (plate 19), the woman flanked by trees makes it unequivocally clear that this is her domain. There are places the tiger cannot go, and this is one of them. But there is an additional dimension to the drawing, the nest. As much as the nest suggests a woman’s domain and resolve, it also represents a longing for family and domestic peace. Many of the nests in Dial’s drawings are empty, however, suggesting a sense of sorrow and frustrated desire.

By presenting these images of women with authority and control (however limited) Dial sets his work apart from other artists. Dial is not relegating his women to the subordinate social position the way the works of Prophet Royal Robertson or Robert Colescott do, but, if that is the case, why doesn’t he represent them in a manner that is more deeply uplifting? Why is it necessary for them to have painted lips, rouge on their faces, and exposed breasts? Why are those elements—along with the display of fish and nests—so central to the thematic content of the drawings?

In pieces where the woman is the protagonist, including those in the Life Goes On series, her position is linked to her struggle and what she is trying to achieve in life. Importantly, in these drawings, women seem to acquire a static quality that suggests the larger arena of feminine concerns. The tiger is always active and amorous in the heat of Friday and Saturday nights. He is always involved. But for the women, there is also the suggestion of restraint of consequences, of Sunday morning, and of the week that follows. Women hold their ground in Dial’s works, seldom morphing like the tiger, who restlessly and constantly changes positions and shape to encircle the woman. The tiger has a freedom, perhaps a power that allows him to act, to change, to do things as the male. The women appear to lack the power to transform. Dial explains: “Wasn’t nobody free back then but the white man. The white woman wasn’t even free. The black woman had a little bit of freedom, ’cause she was in the kitchen cooking for the white man, and washing up his dishes, and going off with him, whatever he asked for. And he prefer the black woman sometimes, and that give the black woman a kind of freedom.”6 Dial’s drawings reflect his understanding of the power that historically the black woman (as a type) has had over her immediate family, as well as over the white master and mistress.

Although Dial’s larger works incorporate the woman and the tiger, the themes in his works on paper veer away from those in the multimedia pieces in noteworthy ways. Art historian Robert Hobbs posits how Dial’s larger works speak to industrialization and its aftermath, unemployment, homelessness, and the death of the American city.7 And, always, Dial offers deeply coded commentaries on the autonomy of race, voice, and the construction of social, cultural, and economic power in the South. His practice of using found objects to craft his large pieces is informed by his work as a house painter, carpenter, and metal worker. Rarely do any of the themes addressed in his large pieces appear in his drawings. His works on paper, which focus on male/female relationships, are much more playful and erotic than the sculptures/constructions. In these works, Dial seems to allow himself to enjoy what he’s doing. They suggest, perhaps, a relief from the monumental, the significant, and the ominous. I see in his drawings familiar moments, so closely related to my own process of making, of making things for the fun of it. There is nothing serious or difficult about the process of making, and as a result the creations are an expression of something accessible, immediate, joyful, and truly wonderful that happens within the process.

When Dial’s practice is viewed in this context, a continuity emerges between Dial’s works on paper and the large mixed-media works: the migration of the found. The migration of the found in Dial’s art speaks to two ideas: first, the ways in which black people in the South have historically located their autonomy in places, objects, and practices beyond the reach or awareness of white concerns; and, second, the way that they have migrated in the pursuit of jobs and liberties through the years. It is only in this context that the term “outsider” has meaning in considering Dial. The “found” in this context focuses on how one experience informs another in totally unexpected ways and in ways that “insiders” may not totally recognize and consequently may miss in their interpretation of a work of art.

One summer, I worked on a road project bundling steel rods for one of my uncles. The experience of working with concrete and steel added to my knowledge of materials—how different media work together, and how found materials can find artistic applications. Similarly, Thornton Dial’s experiences tie directly into what he makes and how he makes it. His work experience (outside art-making) has provided him with impressive body of knowledge that he applies directly to his craft. That “found” knowledge allows him to incorporate materials drawn from a broad landscape, from all that he encountered as he was growing up—the totality of people met, objects found, and events experienced on a daily basis in his community. He observed and learned from others and their work: how neighbors improved and ornamented, painted and enlarged their houses; how they created yard shows with assemblages and paintings.8 All of those things influenced Dial’s art, and it taught him to freely exploit whatever materials were available.

In the beginning of his career as an artist, Dial did not go out and buy materials at the art supply store; he just tapped into the reservoir of what was available to him. This is exactly how I, and so many other artists, make art. We migrate the found object, the new idea, from its original location to the center of our work. Because he had seen it done in so many other contexts, Dial knew that he could reshape any found media. He could bend it. He could do whatever was necessary to make it into what he wanted it to be. He knew it would take time, effort, and creative concentration to do it, and because of his early experiences and employment, he embedded this knowledge into his artistic process. He did it at the beginning, and his is doing it now. Everything he learned in working over the years, he uses in his art, and I mean everything.

As Dial produced more works of art, he learned more. He learned about the techniques and materials he used to make his work and he learned about what would and would not work in art. For Dial, the power of the found and the opportunity to migrate it, renegotiate it, and change it is always about keeping things together.

Of course, Thornton Dial simply experiments; he plays with ideas. It is the luxury of the artistic process to say, “Wouldn’t it be fun just to do whatever,” and then do it. Art that grows out of creative play, while not necessarily representative of the artist’s disciplined practice, provides the opportunity to see what might be made, what might happen. If I want to see what something might look like—I just put it down. There’s nothing serious about it at all. It may mean a lot retrospectively, of course, and may be approached as seriously as anyone wishes, but the object exists because of experimentation and the freedom of play.

For example, I made a piece based on what white people often say about well-spoken black people: “He’s so articulate.” Whites have said this about Colin Powell, Barack Obama, and many others intending to pay a compliment but revealing a chosen ignorance, a preference to believe that there is a true linguistic difference between blacks and whites. My piece, You’re So Articulate (2007) (fig. 4.3), is composed of multiple silhouettes of black heads within a larger head, with white silk roses scattered among them, which I misted with rose fragrance— representing the sweet smell of roses flowing out of those articulate white mouths. I just wanted to see what it would look like, and to remind viewers that a rose by any other name (or speaker) is still a rose.

Dial is a master of artistic play. Artists often arrive at a moment in life—and Dial is certainly at that point—where their reflections turn to the excitement, hardship, and pleasure of youth. Many of Dial’s drawings refer to these reflections. But this is not nostalgia; Dial is not stuck in the past. He remembers, with pleasure, the good times in life. He re-creates and reinvents that life, visually presenting it in terms that are at once autobiographical and generalizations of the larger southern African American experience. As his contemporaries neatly and commonly state, “We all grew up in that life together.” Dial gives me a picture of that life; he records it in his drawings.

This element of play is also evident in the kinetic quality of Dial’s drawings. Everything takes place all at once. I know this. I have been

Figure 4.3 Juan Logan, You’re So Articulate (2007). Acrylic paint, silk roses, vinyl, rose scent, on canvas. 84 × 60 inches. Courtesy of the Collection of Juan Logan.

in that place where I am moving, looking over my own shoulder, looking back and looking forward, aware of where I am, and of everything that is going on around me and in me at that moment. This is how Dial draws the tiger. This is how he draws his woman, aware that she may not be precisely his.

In a drawing like People Will Watch the Struggling Tiger, Dial is not depicting multiple tigers operating within one visual field, but rather, one tiger in constant motion. He is drawing the tiger as the powerful, playful, and elusive figure, the tiger as the being who exists beyond the constraints and conventions of the frame. It may well be that Dial is drawing himself here, as an artist and as a man. In A Lady Will Stand by Her Tiger Life Still Go On (1990) (plate 4), Dial presents the kinetic motion of the heraldic image—a red woman flanked by tigers and birds. The tiger is leaping—praising and engulfing the woman—and pressing the birds, and all their associations with nesting and family, to the margins.

By way of contrast, the woman in this drawing and others, like Life Go On (1990) (plate 18), seems tied down, with an almost palpable heaviness of line. Her hair is filled in, her nose and eyes are weighted down. In one context, that heaviness may be tied to a moment of feminine thoughtfulness. The differences between the way Dial renders women and how he presents the tiger are pronounced. The women are heavy, weighted, statically presented. The tiger appears to be in motion, light, wild, not freighted with hair or facial features. In this way, Dial uses line to underscore the differences between the lives and concerns of the sexes in vivid and evocative ways.

Dial’s works on paper provide a unique opportunity to address the problem of situating Dial in the world of contemporary art. Critics describe him variously as self-taught, outsider, vernacular, and folk. These categories say less about Dial and more about writers and collectors who find them necessary. The description is suspect. As an artist, I question the insistent repetition that experimenting with themes on paper is something typically associated with “outsider artists.” Creating multiples, or working out formal and conceptual ideas on paper, is something that can be seen in the working processes of artists from Picasso to Kehinde Wiley or another number of artists working today. It is almost ubiquitous. It is more common than not. Some artists, like Dial, create larger, more tactile works of art that have a greater presence, if you will, without doing preparatory drawings. And some get there, myself included, by creating hundreds of works on paper. I have so many works on paper that I’ve done over the years that have never been shown. It is, nonetheless, how I develop my larger pieces. I need to do that quick and spontaneous work.

But Dial’s works on paper are not preparatory drawings. Forms, concepts, social relationships find their complete resolution in the works on paper, and stand alone as clearly finished works of art. They earn the title of art not only because of how they relate to the larger three-dimensional works, and not only because of their content and symbolism. Content and symbolism are important, but the quality of the drawing and the use of line is also a factor in how I value Dial’s work. I am always moved by Ellsworth Kelly’s line quality. The simple shift in the weight of the line—thin to thick, light to heavy—lends meaning to a piece, and affects the way in which the viewer relates to the work. Dial does that as well.

When I approach Dial’s works on paper in the same way I do his sculpture and paintings, I begin to appreciate the breadth of his abilities and the depth of his vision. His drawings are as affecting as his larger sculptural works and as strong as his paintings. The drawings possess an immediacy that encourages a second look at the larger works. I think he is talking in the drawings, talking about his life, his relationships, his art. Through these drawings he asks the viewer to consider who holds power here and how it is exercised. The drawings invite a closer examination of the complex and complicated relations between men and women, the social worlds they inhabit, and the construction and perception of power, even when that power is an artifact of outmoded perceptions.

NOTES

1 Thornton Dial: His Spoken Dreams, Ricco/Maresca Gallery, New York, N.Y., November 19, 1998 to January 16, 1999.

2 Thornton Dial, interview with Juan Logan, Bessemer, Alabama, September 25, 2010.

3 Thornton Dial, “Mr. Dial Is a Man Looking for Something,” in Souls Grown Deep: African American Vernacular Art of the South, vol. 2 (Atlanta: Tinwood Books, in association with the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture and The New York Public Library, 2001), 208.

4 Thornton Dial, interview with Bernard Herman, Bessemer, Alabama, April 15, 2010.

5 Robert Hobbs, “Richard Dial: Seating and Unseating Tradition,” in Arnett and Arnett, eds., Souls Grown Deep, 2:484–89.

6 Thornton Dial, “Mr. Dial Is a Man Looking for Something,” 198. See also Ernest J. Gaines, A Lesson Before Dying (New York: Vintage, 1997). Gaines deploys the taut relationship between a white plantation family and the African American cook they once employed as a means to explore the depth, difficulty, and fragile nature of power in the segregated South.

7 Hobbs, “Richard Dial,” 484–89.

8 William Arnett, interview with Juan Logan, Atlanta, Georgia, September 25, 2010.

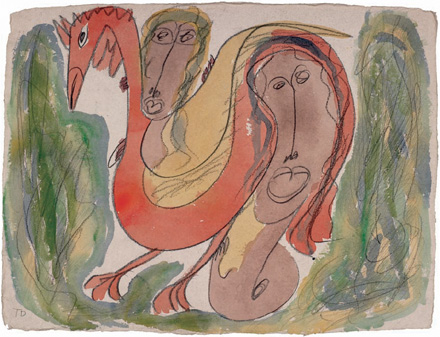

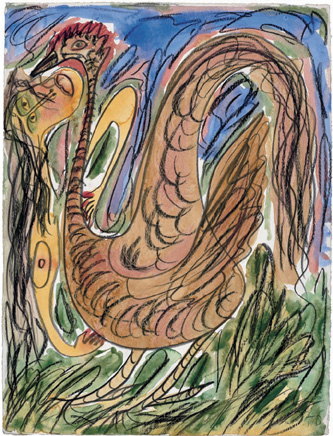

Plate 46

Rooster Picture, 1991

watercolor

30 × 22  in. (76.2 × 56.7 cm)

in. (76.2 × 56.7 cm)

Courtesy of the artist and The Souls Grown Deep Foundation

L2010.22.31

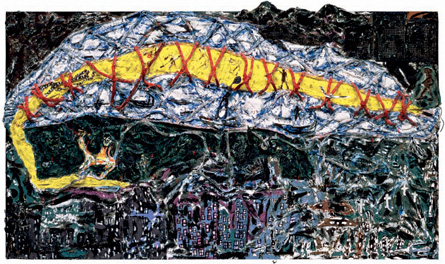

Plate 47

Ladies Know How to Hold a Rooster, 1991

watercolor

22  × 30 ¼ in. (57.9 × 76.8 cm)

× 30 ¼ in. (57.9 × 76.8 cm)

Courtesy of the Collection of Ron and June Shelp

L2010.22.5

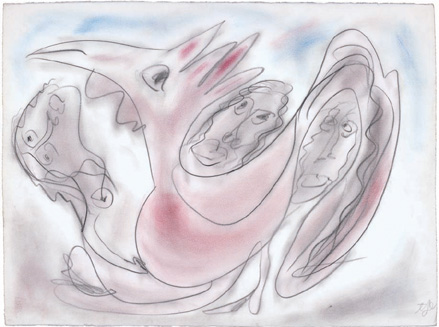

Plate 48

Ladies with a Rooster, 1991

watercolor

22  × 30 in. (56.7 × 76.2 cm)

× 30 in. (56.7 × 76.2 cm)

Courtesy of the artist and The Souls Grown Deep Foundation

L2010.22.12

Plate 49

Rooster Picture, 1991

watercolor

31 × 22 ¼ in. (78.7 × 56.5 cm)

Courtesy of Martha Howard Collection

L2010.21.1

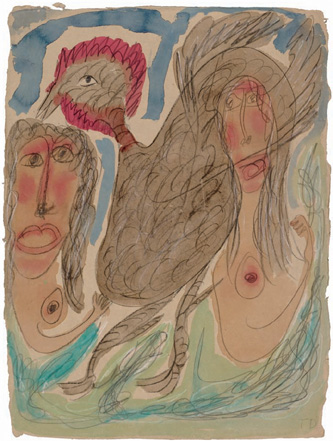

Plate 50

Rooster Picture, 1991

watercolor

30 × 22 ⅝ in. (76.2 × 57.5 cm)

Courtesy of Mr. Tom L. Larkin

L2010.20.7