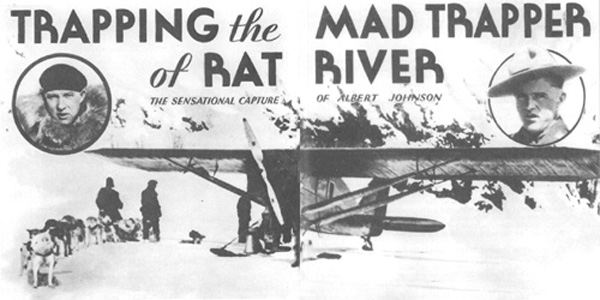

The above title and illustration, reprinted from True Detective Mysteries, shows supplies being transferred from the Bellanca to a dog team during the Johnson pursuit. The inset photos are of Wop May, left, and Constable Millen.

Wop May

(As already noted, among those involved in the blizzard-shrouded pursuit of Albert Johnson was World War One fighter ace and famed bush pilot W.R. “Wop” May, DFC. In 1932, in collaboration with H. R. Kincaid, he wrote an account of his experiences which appeared in True Detective Mysteries and is reprinted courtesy the magazine. The photos are somewhat dark since no archives in Canada seems to have them and they have been reproduced from the original magazine article. It is the first time that they have appeared in a Canadian publication.)

Canada’s Northland was aroused as never before when Sergeant Riddell mushed into Aklavik with the news of Millen’s murder. Once again the local radio station, UZK, broadcast Inspector Eames’ appeal to trappers and Indians to join the hunt; and over the moccasin telegraph, UZK’s prehistoric cousin, the word was also carried all over the Arctic.

“Get the mad trapper of Rat River!” became the watchword of the North from February 1 onward; and that day saw every man fit to take the trail mushing for Aklavik behind his dog-team.

Meanwhile, at police headquarters, Inspector Eames was marshalling his forces and laying plans for a new campaign against the murderer

The Inspector was faced by the tremendous handicap that Arctic dwellers, up to that time, had never overcome — the problem of transporting bulky supplies of food, ammunition and dog rations over long distances and through 45-below blizzards. But with a touch of genius Inspector Eames solved that problem in a flash.

He would have an airplane sent in from the “outside” if possible. It would assure ample supplies for his posse without long, heartbreaking marches over the frozen tundra from Aklavik. It would permit both men and dogs to conserve their strength for the primary task of running Johnson down. It would also prove invaluable in scouting the fugitive’s position, and speed up communication between Aklavik and other posts lying in the surrounding district.

A plane might also be used to bomb Johnson’s stronghold, in the event that aerial bombs were available at Edmonton; and a machine-gun, mounted on the plane, might also be used for an overhead attack.

As a consequence on February 2, I received a wire from “Punch” Dickins, Canadian Airways Superintendent at Edmonton, asking me if it would be possible to fly down to Aklavik and join the Mounted Police in their search. I replied that I was ready to undertake the flight. I received an answering wire from Punch saying he would fly into Fort McMurray, my base, next morning with two Mounted Police officers and a supply of teargas bombs.

Next morning, with the thermometer at 35 below, Punch swooped in from Edmonton. I had my engine already running on our ‘drome on the Saye River, and we hurriedly transferred the supplies and the tear-gas bombs. Constable Carter, who was going North to replace the murdered Millen, climbed in with me and my air mechanic, Jack Bowen, a veteran of the Arctic. A minute later I had given her the gun and we were soaring down the Athabasca, off on our 2,400-km (1,500-mile) hop to the town of Aklavik.

Flying low in the shelter of the steep banks of the Athabasca, we roared along at 190 km (120 miles) an hour. The weather was fairly good despite the low temperature for the first 160 km (100 miles) of our journey. Thereafter we ran into snowstorms, and by the time we were approaching Fort Smith a blizzard was howling up the river from the Arctic. Since there was no time to be gained by hurrying past Smith and possibly being forced down in the wilderness beyond, I decided to spend the night at the post. We had completed 425 km (265 miles) of the northward hop when we landed in the storm with the shadows of the long Arctic nights creeping in.

Next day, although the weather was threatening and the thermometer way down to 30 below, I decided to hop off. We again sped down river, keeping low in the shelter of the river banks to avoid the stiff north wind. As I feared, we again ran into snow about an hour north of Fort Smith and fifteen minutes later we were ploughing, almost blind, through a howling blizzard. By noon, we had reached Fort Simpson, 740 km (460 miles) down river from Fort Smith, so I landed there and spent the night.

The weather was still pretty bad next morning and the thermometer had dropped another 15 degrees to 45 below. However, we finally decided to start for Fort Norman, 480 km (300 miles) further north. That day was one of the worst that I have ever experienced in the years I have been flying in the Arctic. We bucked snowstorms and gale-force north winds all the way down the river. Near Fort Norman, at 1,200 m (4,000 ft.), the wind had increased to hurricane force. Although at times I had my throttle wide open, we were being blown backward over the ground. Then a blizzard blotted out the earth and left us bumping about up there, completely blind. I guess both Carter and Jack were glad to see the snow under our skis when I eased the Bellanca down to a landing in the storm. I know I was. We had been four hours making the 480-km (300-mile) journey, and our average cruising speed was 190 km (120 miles) an hour.

It was still 45 below zero when we went to our machine next morning and started to dig her clear of the drifts. But the storm had abated, and we took off for Arctic Red River at the junction of the Arctic Red and the Mackenzie Rivers. There I received instructions to meet Inspector Eames’ posse at their main camp at the mouth of the Rat and Peel Rivers. We hopped over there from Arctic Red River, but since there wasn’t a sign of the posse, I flew on to Aklavik where we spent the night.

Aklavik was storm-swept next morning, a blizzard swirling down from the Arctic on an icy north wind. Again we dug the machine out of the drifts and by 11:35 the storm had abated enough to let us get into the air. I took Doctor Urquhart, Constable Carter, and Jack with me, and flew through snow flurries to Inspector Eames’ main camp at the mouth of the Rat and Husky Rivers.

Again I was unable to find their camp but I continued up the Rat to its junction with the Barrier. Suddenly, I saw four men spread out on the snow, creeping up on a clump of bushes on the bank of a creek.

I circled over them trying to spot their objective, but I could see nothing. Finally, they stood up. I learned later that they had been crawling up on a camp where Johnson had spent the night.

I was able to pick up Johnson’s trail at this camp. So, flying with our skis almost brushing the snow, I followed his tracks up the Barrier River about 8 km (5 miles). Here the fugitive had circled and come back along his own trail for a distance, as though watching to see if he was followed. There, the fleeing trapper had turned away from the Barrier River, striking westward through a mountain valley toward the range that separated Yukon and the Northwest Territories. His trail disappeared when he came to a snow plain beaten as hard as ice by the scouring winds from the north. I spent half an hour circling over that area trying to pick up his tracks again. But, as the light was failing and I still had to find the posse’s camp, I was forced to abandon the search.

I backtracked along Johnson’s trail to his old camp. There I picked up the trail of the posse and flew along it to the Mounties’ advance camp on the Rat River. I searched for fifteen minutes for a place to land, eventually deciding on a tiny plain between two towering hills. I set the Bellanca down, and I don’t mind saying I was mighty proud of that landing. It was a tough spot to get into. In fact one of the greatest handicaps we faced throughout the search would prove to be finding landing grounds in the tangle of hills, box canyons, creeks and rivers. We were working continually over a mighty treacherous country where an engine failure made a crash inevitable, and where the slightest error in judgement, landing or getting off, would have meant a crack-up.

A view from 9,145 m (30,000 ft.) of the winding Rat River and general area where Johnson killed Constable Millen.

A constant problem for May during the search was finding a piece of ground flat enough to land on.

Department of Energy, Mines and Resources

I got into communication with the camp and made arrangements to bring the posse supplies and dog feed from Aklavik. Constable Carter, who had flown in from Edmonton with us, left to join the posse. With Doctor Urquhart and Jack, I flew back to Aklavik for the night.

Next morning (February 8) UZK picked up a message from Inspector Eames asking me to meet him at the advance camp on Rat River. Jack and I loaded the Bellanca with supplies and dog feed, dug her out of the snow drifts and hopped off for the Rat. The thermometer was down to 45 below, and a flying scud of snow whipping in from the north on a piercing wind froze the marrow of one’s bones.

This photo by Wop May shows the hazardous terrain over which he flew and through which the posse battled in blizzards and sub-zero cold.

Wop May

I met the Inspector at the Rat River camp. Here I learned of the terrible difficulties his posse had encountered on their trip from Aklavik.

Mushing out of Aklavik, the Inspector said they had found the trails buried in 120 cm (4 ft.) of soft snow. Throughout that day, turn by turn, the posse toiled ceaselessly through the drifts, tramping out trail with their snowshoes for the straining dogs. The storm continued to rage all that night and throughout the succeeding four days. Each day found the posse wearily tramping out trail and battling the subzero wind. Throughout that ninety-six hours, their field of vision had been limited to 9-13 m (30-45 ft.) by whirling snow clouds. It required all their trail craft to keep on their course. So slow was their progress, the Inspector said, that they did not reach Johnson’s barricade until the following Saturday.

We found the posse encamped in the brush along the Rat River. The men were living in their canvas tents floored with spruce boughs, with small portable stoves to keep them warm and, Arctic fashion, sleeping on caribou skins under eiderdowns. Their tents, when we arrived, were practically buried in the drifting snow.

Included in Inspector Eames’ posse at this time were Sergeant Riddell, Sergeant Hersey, and Constable Carter; trappers Noel Verville, Carl Gardlund, Frank Lang, Jack Ethier, Frank Carmichael, Pete Stromberg, and a number of other trappers and Indians. In addition, the Reverend G. Murray, Anglican rector of Aklavik, had mushed out with the Mounties to help in rounding up the mad slayer of Constable Millen.

After discussing plans with Inspector Eames and warning the posse of Johnson’s habit of backtracking and watching his own trail, I took Sergeant Riddell, who was familiar with the country, on a flight to search for Johnson’s trail.

The light that day was very bad, even for the Arctic, with low-hanging clouds and a gusty wind hinting at a new blizzard. We flew down the Rat River, crossed through a 610-m (2,000-ft.) pass over the mountain range that lay on the Yukon-Northwest Territories boundary, and circled the Yukon country. Although we covered over 240 km (150 miles), we didn’t find a trace of Johnson’s trail. By the time we got back to the posse’s camp, the threatening storm had broken in a flurry of snow. Jack and I loaded Constable Millen’s body, frozen as hard as iron, into the Bellanca and I hopped back to Aklavik.

Next day (February 9) one of the worst blizzards that I have ever seen was blowing, making it absolutely impossible for us to leave the ground.

By the following morning the storm had blown itself out, but the temperature was once more down to 45 below. Jack and I, after digging the Bellanca out of the drifts, again took off for the posse’s camp, carrying supplies and with Joe Verville, a brother of Noel, as a passenger. When we arrived over the Rat River camp the wind was blowing a gale. Snow, as fine as talcum powder in the extreme cold, was blown 300 m (1,000 ft.) into the air. It was impossible for us to see the ground. I turned back to Aklavik, and flew practically blind down the treacherous, winding Rat River Pass, expecting any moment to bump into one of the snow-covered hills along its course. That was a hair-raising flight, if I ever made one.

We landed at Aklavik at 11 a.m. and waited three hours to see if the gale would moderate with the waning day. At 2 p.m., although a strong wind was still blowing, I decided to try it again. Over the Rat we found conditions worse — if that was possible. I managed, however, to land my supplies at the mouth of the river. I flew from there to Arctic Red, picked up more supplies, and took them back to the Rat. Then, with the posse assured of supplies for a couple of days, we returned to Aklavik after one of the worst flying days in my experience.

During these two days the ground party had been practically storm-bound in their Rat River camp. Some members of the party, though, had taken the trail the second day, but the howling gale and the hurtling snow made it impossible for them to pick up any sign of Johnson’s trail.

On February 11 I took off once more from Aklavik with Joe Verville as passenger and a load of supplies, dog feed and ammunition. I swooped in to land on the side-hill where I had been sitting down on my previous visits to the camp and where there had been several feet of hard-pack snow. At the last minute before my skis touched the ground I realized that the gales of the previous two days had scoured the snow practically down to rock. I braced myself for a crash. But the old Bellanca settled down as though there were 6 m (20 ft.) of snow under her skis instead of 4 cm (1½ ins.). I drew a long breath of relief.

Since a bad wind was still whipping across the hills, we hurried the job of unloading supplies. Nevertheless, the wind had again strengthened to a gale before we finished this task and I was compelled to take off hurriedly to save the machine. I flew to Arctic Red River for another load of supplies, landed them at the Rat, and then went back to Aklavik when we found weather conditions made it impossible to search for Johnson’s trail.

During this time, members of the ground posse had at last found traces of Johnson’s trail further up the Rat. They reported that his tracks wandered in and out of the Divide, sometimes in an apparently aimless manner. At frequent intervals Johnson had backtracked cunningly, taking advantage of the broken country to watch his own trail and ambush pursuers.

But most significant to the trail-wise eyes that were scanning his tracks was the irregular spacing of the snowshoe prints. There was exultation in the voices of the posse as they declared that Johnson’s tracks showed that he was starting to weaken under the deadly grind of keeping the trail. He was no longer striding out strongly as he had done in the days when the hunt had been young 80 km (50 miles) further down the Rat.

Next day, in 35-below weather with the wind still blowing frigidly from the north, I flew to the mouth of the Rat for a conference with Inspector Eames and Sergeant Riddell.

“Johnson is undoubtedly heading for the Yukon,” Inspector Eames told us. “And, although his latest tracks indicate that he is weakening, he’s at least two days ahead of us. He must have been hitting the trail through those two days of blizzard. He may have had a rest since then, of course.

“I think we’ve got too many men in the field. It’s a terrible strain keeping them supplied with food, dog rations and ammunition, and so I’m considering sending some of them home. if we could definitely establish that Johnson’s in Yukon, we won’t need them anyway, for we can’t keep them supplied there.”

Eventually, it was decided that Riddell and I should attempt another scouting trip across the Divide into Yukon. We therefore took off, swung up the Rat and again crossed the tortuous, dangerous pass that crossed the Divide at 610 m (2,000 ft.). We flew as low as we possibly could under existing weather conditions, but failed completely to find a trace of the fugitive and returned to Eames’ camp.

There, at last, we heard the most welcome news that had come to the posse in many days. Shortly after Riddell and I had started, Constable A.

The posse ready to mush out from one of their wilderness camps. The team in the foreground is driven by Sergeant Riddell, standing behind the sleigh.

Wop May

May, Mounted Police officer from Old Crow Post in the Yukon, mushed into Inspector Eames’ camp to join the hunt. May was accompanied by Frank Jackson, a grey-haired, huge-bodied trader who had been at La Pierre House for years, and who knew that section of Yukon better than any other white man. Another trapper, Frank Hogg, completed May’s party.

These three had had no inkling that Johnson was Yukon bound in his flight and the Inspector, who had been hoping that they had brought definite information, was disappointed. But half an hour after they had mushed into camp an Indian, Peter Alexei, also from La Pierre House, came flogging his dog team into camp as though the devil were on his heels.

“Johnson is in Yukon,” Alexei shouted to the Inspector as soon as he stopped his dogs. “Some hunters saw his tracks along the Bell River two days ago. Another hunting party passed along there just a few hours earlier, and there wasn’t a sign of tracks. They went out from La Pierre House and examined them — and they were Johnson’s all right! We found them about a mile below the post!”

Alexei, breathless with excitement, went on to tell the posse that the Indians in the La Pierre House territory were terrorized by the news. They had abandoned their trap lines and fled into the post.

“That’s our man, all right!” Inspector Eames said with an air of quiet conviction. “I don’t think there’s the slightest doubt about it. He’s managed to get across the Divide, and he’s hitting west into Yukon!”

The Inspector sat silent for a moment, a suggestion of admiration in his eyes. “That man’s some musher! Ninety miles in three days — without dogs — and through blizzards! But I think we’ve got him — at last!”

The Inspector decided to send a ground party over the Divide into Yukon, while he, with other members of the party, would fly west to La Pierre House.

He ordered Sergeant Hersey, Constable May, Frank Hogg, Frank Jackson, Jack Ethier, and Peter Alexei, with two Indian interpreters, to make the passage through the mountains by dog team. The air party included the Inspector, Sergeant Riddell, Carl Gardlund, Jack Bowen and myself.

The ground party took the trail that morning and, about the same time, we flew back to Aklavik to pick up supplies, dog feed and ammunition to be flown into the new search area.

Next morning (February 13) we hopped off for La Pierre House, an ancient trading-post on a loop of the Bell River, necessitating a 160-km (100-mile) flight. Up the Rat we ran into a smother of gale-tossed snow that blotted out the landscape and made our attempt to cross the 2,450-m (8,000-ft.) range of mountains exceptionally hazardous. We struck the wrong pass on our first try and floundered around, almost blind with jagged peaks sticking up under our wing tips.

I was sweating plenty under my parka, and it wasn’t with the heat, either, when we finally found the right pass and came down out of the smother on the Yukon side. We found a heavy snowstorm in progress at La Pierre House. After we landed I was compelled to taxi the Bellanca up and down for half an hour to make a runway so I could get off again.

A ground party was sent from La Pierre House to examine the tracks south of there. They returned that night and reported that they were unquestionably Johnson’s, but that they appeared to be at least four days’ old. Although we received that information in a rather crestfallen manner, it compelled the admission that this man Johnson was a superman on the trail. It seemed almost incredible that a man without dogs could make such time under such terrible trail conditions.

Early next day (February 14) I again took off to follow Johnson’s trail. I picked up his tracks without difficulty in the deep snow at La Pierre House and followed them easily around the looping bend of the Bell River for over 40 km (25 miles). But where the Eagle River flowed into the Bell thousands of caribou had left a wide, hard-packed trail on the river bottom.

Here Johnson had discarded his snowshoes. His trail had vanished once more!

I cast about in wide circles to try to pick up his tracks again, but the fugitive, sticking cunningly to the caribou trail, had covered his retreat. So I flew back to La Pierre House. On the way I saw where the posse could gain a tremendous advantage by cutting across country. It was 40 km (25 miles) following the Bell River loop along Johnson’s trail, but by taking the overland route, the posse could accomplish the distance to the mouth of the Eagle River in less than half that distance.

I recommended this route to Inspector Eames when I landed back at La Pierre House. He immediately adopted my suggestion. Right there the posse gained at least three days on their quarry.

I found Inspector Eames had been investigating Johnson’s trail from the ground. South of La Pierre House, evidently warned of the proximity of the post by howling dogs, the fugitive had made a wide detour, swinging back to the Bell River west of the trading center. He camped one night less than a mile west of the post. Farther west still, the ground party discovered where Johnson had laid a fire. Then something, possibly the howling of dogs, frightened him and he had dashed off again on his mad westward trek. Still farther west, the pursuers found Johnson’s snowshoe track was again wobbling pitifully, indicating that he was once more on the verge of exhaustion. The heavy snows and the unremitting exertion were cutting into even his iron constitution.

The only way that mechanic Jack Bowen and Wop May could service the Bellanca in the frigid weather was by laboriously covering the engine with a tent.

Wop May

This photo shows the skis that enabled the plane to successfully challenge the deep, powdery snow.

Wop May

The Inspector informed me that supplies at La Pierre House were practically exhausted. Food especially was short since the Indians who had flocked into the post on the word that the “mad trapper” was in their midst had consumed practically everything. I decided to fly back to Aklavik, pick up supplies there, and gas and oil for my machine.

But once again I encountered trouble in that treacherous 610-m (2,000-ft.) pass through the mountains. A blinding snowstorm was whooping through the pass when Jack and I arrived. Once again we floundered around among those jagged peaks for a hair-raising quarter of an hour before I gave up and went back to La Pierre House.

About midnight, the ground party which mushed over the Divide staggered into the post. Men and dogs were completely worn out by their battle with deep snow, lashing gales, and the fierce cold of high altitudes. They lay like dead men that night, asleep almost before they had crawled under their eiderdowns.

Next morning (February 15) when they awoke, snow was still falling heavily and a frigid wind still blowing from the north. But they hitched up their whining dogs and flogged them into the storm, bound by the overland route for Eagle River where Johnson’s trail had disappeared in the maze of caribou tracks. Inspector Eames and Sergeant Riddell again took the trail with them, making a party of eleven. They included Constable May, Sergeant Hersey, Verville, Gardlund, Ethier, Jackson, Alexei, and two Indian interpreters.

A common occurrence during the northland pursuit — digging the plane out of a heavy snowfall.

Wop May

I thought, as I watched that party tramp stolidly out into the whirling snow that morning, that I had never seen a more determined body of men. The discovery of Johnson’s faltering tracks had spurred them to a dogged resolve that the fugitive would henceforth get no rest — no chance to recoup his failing strength. I wouldn’t have wanted those men, in their frame of mind, on my trail!

By noon the storm had cleared sufficiently to allow Jack and me to start for Aklavik. We spent three hours digging the old Bellanca out of the snowdrift and soared away to try our luck again with the pass. This time we had no difficulty, and arrived back at La Pierre House that afternoon heavily laden with supplies, ammunition, gas and oil.

Next day, the weather was again completely impossible. Throughout the brief hours of daylight the snow fell so thickly that it was impossible to see for more than a few yards. We sat helplessly in La Pierre House and wondered if Johnson was making another 32-km (20-mile) gain on us. We also felt plenty sorry for men and dogs who were out on the trail in such a storm.

February 17 dawned in a grey blanket of fog and snow, but by 10:30 the fog had lifted enough to give some semblance of visibility. Jack and I, shovelling like slaves, dug the Bellanca out of the night’s accumulation of snow, got her running and then swung off northward for Eagle River.

Since I arranged with Sergeant Riddell for him to place arrows along his trail, Jack and I had no difficulty in following Eames’ posse. We cut across the wide-swinging loop of the Bell on their track and in a few minutes sighted the Eagle River.

This stream, winding like a snake through precipitous banks, flowed down from a range of hills southwest of the Bell, and joined the latter river about 50 km (30 miles) west of La Pierre House.

We were droning along about 190 km (120 miles) an hour when I glanced down to the river bottom. I saw a black speck on the ice in the center of the stream. Puzzled, I stared at it for a second. Then perhaps 360 m (1,200 ft.) south of the lone speck I noticed half a dozen other specks spread out at the foot of the steep eastern bank of the river. A movement on the high western bank directed my attention to two more specks standing out clearly against the dead white of the snow background.

A glinting flash caught my eye near the east bank.

Then, with a fierce thrill, the significance of the scene struck me. That lone black speck in the center of the river was Johnson — the mad trapper! The other specks were the posse crouched along the river bank in its cover. And that glinting flash was the flame of a rifle.

Johnson, at last, had been brought to bay on the river ice. He was again matching his rifle against the rifles of Eames’ command.

Would they “get him” this time? Or would his luck still hold? And would we go on chasing him up and down through these hills, up and down these rivers through blizzards and cold and the dingy half-light of Arctic days?

My mind seething with these thoughts, I cut my motor and glided down above the river bottom. Above the keening of the wind around the Bellanca’s skin I could hear the crackle of the rifles below. Watching with fascinated eyes, I also could now catch the flash of the weapons and see the snow dance under the impact of the bullets.

As I swept over Johnson, scarcely 15 m (50 ft.) above him, I could see where he had dug himself a shallow lair in the hard-packed snow of the river bottom, and tossed his pack on the snow in front of him to hide his movements from his foes.

I heard his rifle crack as I opened the throttle and flew south in a wide circle. We came roaring back down the river. Once again I peered down at Johnson in his snow trench as we raced overhead. Then, as I passed over the posse, I saw a figure lying on a bed-roll near the west bank. I realized, with a sick feeling, that one of our party had been hit.

Who was it? And was he dead?

Busy with these torturing thoughts I circled and came back upriver, passing over the posse and Johnson. As I flew over the fugitive’s lair it appeared to me that he was lying in an unnatural position. When I came back the next time, I nosed the Bellanca down until our skis were tickling the snow on the river bottom. Johnson, I could plainly see as I flashed past, was lying face down in the snow, his right arm outflung, grasping his rifle.

There is something about the way a dead man lies that is unmistakable. I knew, as I looked at Johnson, that he was dead. The Mounties had “got their man.” The chase was over!

I rocked the Bellanca back and forth on her wing-tips to signal Johnson’s death to the posse. Then I landed on the river bottom and taxied over to where I had seen the man on the bed-roll.

“Who’s hit?” I called as Jack and I clambered out of the machine. Sergeant Riddell, who was bending over the wounded man, answered: “Sergeant Hersey.”

“Badly?” I asked.

“I’m afraid so.” Sergeant Riddell’s face was grave for Hersey was his particular pal. “He’s wounded in the left knee, and it may have gone up into his stomach.”

I considered a moment, and then said: “Get him fixed up as well as you can and I’ll fly him to hospital at Aklavik.”

Sergeant Riddell started to prepare Hersey for the trip, and I strolled up the river toward Johnson’s lair where members of the posse were staring at the dead man. As I joined the crowd, Verville turned to me and said: “Just look at his face, Wop. Did you ever see anything like it?”

I stepped around to get a look at Johnson’s face. He was lying face down on the river. As I stooped over and saw him, I got the worst shock I think I’ve ever had.

Johnson’s lips were curled from his teeth in the most terrible sneer I’ve ever seen on a man’s face. The parchment-like skin over his cheek bones was distorted by it, while his teeth glistened like an animal’s through his days’-old bristle of beard. It was the most awful grimace of hate I’ll ever see — the hard boiled, bitter hate of a man who knows he’s trapped at last, and who has determined to take as many enemies as he can with him.

After that sneer, I couldn’t feel sorry for this man who lay dead in front of me. Instead, I was glad that he was dead. The world seemed a better place with him out of it.

I sneaked another look at that sneer. Then, cold with aversion, half sick, I turned away. I knew that the other members of the posse felt the same way as I did as we walked away from Johnson’s body. At the Bellanca where Riddell was preparing Hersey for the flight to hospital, I heard the story of Johnson’s last stand as the posse had seen it from the ground.

Early that morning, they told me, they had broken camp near the mouth of the Eagle River and started upstream along the caribou trail. Inspector Eames, armed only with a revolver, had been the first to mush out along the frozen river behind his dogs and, during the first hour and a half, had led the posse.

Then, however, Hersey overtook the Inspector and forged into the lead. The fact that Hersey’s dogs were slightly faster than the Inspector’s was the lucky circumstance that saved Eames’ life. For Eames, armed only with a revolver, would have been no match for Johnson’s deadly rifle, although the Inspector is one of the best revolver shots in the Arctic.

Hersey sighted Johnson first as he rounded a bend in the river. The fugitive was frenziedly trying to scramble up the steep, ice-crusted river bank and take cover in the brush. Johnson finally abandoned his attempt and flung himself down facing Hersey.

The Eagle River from 9,145 m (30,000 ft.), showing the bend where the posse caught up to Johnson.

The inset photo, taken by Wop May, shows Johnson dead on the ice, and part of the plane’s wing and air speed indicator.

Department of Energy, Mines and Resources

The Sergeant seized his rifle from the sleigh, and dashed toward the center of the river bottom to get a better view of the fugitive. Verville, in the meantime, had joined Hersey and they took up positions a short distance apart. Hersey was kneeling on one knee sighting his rifle, calm and unflustered, when Johnson hit him. Verville, wincing, saw the Sergeant topple over and collapse on the ice.

The other members of the party — Sergeant Riddell, Constable May, Gardlund, Jackson, Ethier, Alexei and the two Indians — had heard the rifle shots. They came dashing around the bend in the river, dog-whips cracking as they sped along the trail, eager to get into the battle.

Johnson, seeing these reinforcements, instantly decided upon flight. He sprang up and started at a shambling gallop back along his trail. Behind him, the members of the posse raced to the river bank.

One by one, the rifles of the party roared into action. Under the volley Johnson suddenly staggered and then toppled to the ice. Members of the posse saw him dig himself frantically out of sight in the hard-packed snow then toss his bed-roll in front of him as a shield.

Taking advantage of the cover along the river bank, the posse worked its way closer to the fugitive. Around the bed-roll the snow danced as rifle bullets ripped their way through it.

Johnson’s blazing rifle answered shot for shot, and the crackle of his bullets kept the posse crouching behind their cover.

It was at this stage of the battle that Frank Jackson, the veteran La Pierre trader, gave a demonstration of cool courage that was to be talked about in the Northland for many months.

“I’m out of ammunition, boys!” Jackson yelled to his posse mates. “I’ll range for you.”

With these words, Jackson heaved his huge body out from behind a bush where he had been lying and calmly walked up the river bank. From this point of vantage, looking down on Johnson’s position, he called out ranging directions.

“A little high — a little low — a little to the right!” Jackson shouted to the posse as their rifles crashed in the river canyon below him. Jackson was still directing their fire, as though he was on a rifle range, when I finally swooped down over Johnson’s trench and signalled that he was dead.

By this time, the members of the posse had picked up Johnson’s body and his bullet-riddled bed-roll and loaded them upon Verville’s sleigh for the trip back to La Pierre House. There followed the maddest battle with a husky team that I have ever seen. Verville’s dogs, terrified by the grim burden lashed on their sleigh, howled dismally and fought against taking the trail. But Joe tore into them with butt and lash and, as I turned away to start for Aklavik with Hersey, we could hear Verville’s dogs howling a death march down the frozen river. It was one of the weirdest sights I had ever seen in the North.

Sergeant Riddell, in the meantime, had prepared Hersey as best he could for the flight. The wounded officer was not bleeding much from his wound and was fully conscious. But it was a difficult task getting him into the Bellanca and in a comfortable position. Finally, Jack Bowen decided he 74 could carry him best on his knee. I took Sergeant Riddell along with us in case we should have a forced landing since it was impossible for Jack to get out of the machine with Hersey on his knee.

With four of us in the Bellanca’s cabin, I gave her the gun and we were off on our 200-km (125-mile) flight to Aklavik.

As I climbed out of the crooked Eagle River and hit across country for the Bell, I wondered what sort of weather I would find in that treacherous pass through the mountains. I wasn’t long in finding out.

As I climbed through the hills, the Bellanca was nosing through thick fog. When we finally hit the pass at 610 m (2,000 ft.) I couldn’t see both sides of the canyon at once. But there wasn’t to be any turning back this trip — Hersey’s life might pay the forfeit. I shut my teeth and let the old Bellanca drone along, and hedge-hopped through. More than once I thought we were sunk when a jagged peak leaped at us through the murk, and whistled past within a few inches of our wing-tip.

But we got through. Fifty minutes from the time of taking off from the Eagle River we had Hersey in hospital at Aklavik and Doctor Urquhart was cutting his parka off.

The Doctor found Hersey gravely wounded. Johnson’s bullet had struck him in the left elbow, ploughed through his left knee, drilled his arm near the armpit, and then ripped through his body, piercing both lungs in its passage. The bullet was found just under the skin in the Sergeant’s back.

Doctor Urquhart’s face was grim when he had completed his examination of Hersey, and stopped the hemorrhages from the lungs.

“He’s in a very serious, condition — very,” the Doctor told us. “But we may pull him through. Another half hour would have finished him. It wouldn’t have taken those hemorrhages long.”

I felt repaid for that blind flight through the pass, although it had been nip and tuck in more ways than one.

We stayed in Aklavik that night and Jack and I hopped off again next morning to once again challenge the stormy mountain pass. This time, though, we sailed through without difficulty and landed at La Pierre House in fairly good weather.

I learned further details there from Inspector Eames of the final phases of the hunt.

Johnson, it had been learned, had crossed the Divide over the highest peak — over 2,400 m (8,000 ft.). Apparently he had been afraid to keep to the pass. That trip over the mountains must have been one long agony for him. Since there wasn’t a scrap of firewood available, the fugitive must have spent at least one night in that high altitude without a fire.

We marvelled anew at the tremendous vitality this man must have possessed and the indomitable will power he had shown in tackling the mountains. Few people in the Arctic cross those mountains in the winter-time, even with dogs and plenty of supplies, unless they are compelled to.

The police had learned that Johnson was wounded many times in his last stand. The first bullet which had struck him as he was fleeing from the posse hit his hip pocket where he was carrying part of his ammunition. This ammunition had exploded with the impact, tearing a huge wound in his hip. All the other wounds were in his legs, back and shoulders. The bullet which ended the fugitive’s grim life had passed through the small of his back, severing his spine.

Johnson, the police discovered, had been in terrible physical condition at the end. His feet, legs and both hands were frozen, probably during that night when he had been caught without a fire in the high border mountains. He was thin to the point of emaciation. He had a lard tin for making tea but no cooking utensils. The only bit of food that he had carried was a squirrel which he had evidently shot just a short time before he encountered the posse.

The fugitive had been a walking arsenal. He was armed with a .30-30 Savage rifle, the weapon which had laid three men low in the course of his seven weeks’ battle with the law. He had fired every round in it during the last battle, and had been in the act of re-loading when a bullet ended his life. In addition, Johnson carried a .22 caliber rifle and the 16-gauge shotgun that he bought the previous fall in Fort McPherson.

Dr. J. W. Urquhart, second from right with hand in pocket, saved the lives of both Constable King and Sergeant Hersey. Others in the photo include, from left, Corporal R.W. Wild, Mrs. Urquhart, Inspector Eames and Constable A. Milvin.

Glenbow Archives

The shotgun was the most amazing weapon seen in the Arctic Circle. It had been sawed off within a few inches of the stock.

“A sawed-off shotgun in the Arctic,” Inspector Eames commented, “that’s a weapon that has never been known before here in the North. It’s the weapon that gangsters and murderers use in the big cities in the South. What use could a weapon like that be to a trapper? And where would a trapper — especially a ‘bushed’ trapper — learn to saw off a shotgun?”

I, too, pondered these questions for a long time. And I shuddered as I thought of what might have happened if the posse had met this murderous weapon at close range.

Johnson had been plentifully supplied with ammunition, too. In his pocket when his body was searched at La Pierre House the police found between thirty and forty rounds of .30-30 caliber rifle cartridges. All were the explosive type used for hunting big game — particularly deadly in their action. In addition, Johnson carried between fifty and sixty rounds of .22 ammunition together with a few shells for the sawed-off shotgun. The contents of his pockets amazed the police when they turned them out.

On him Johnson had over $2,500 in canadian and United States currency — a fortune in cash for the Arctic, where most trappers conduct their transactions on trading certificates of the posts with which they do their business. That wasn’t the only surprise, either!

A small quantity of gold dust was found in a leather poke, and the police also discovered two gold bridges, presumably from a man’s mouth. And — a most sinister circumstance — neither of those bridges came from Johnson’s mouth. Who, the police asked, was this man who carried in the Arctic gold bridges ripped from the mouths of other men?

An ordinary, open-blade razor, an axe, and a pocket compass, in addition to his bullet-riddled bed-roll, completed the equipment with which Johnson had been keeping the trail in the last days of the chase. Police believed that the fleeing trapper had carried cooking utensils with him at the start of his flight, but had probably discarded them as he weakened under the strain of the tremendous pace.

The examination of Johnson’s belongings revealed another strange trait — everything was wrapped in cloth. His money, divided into a number of small rolls, was stowed away in every pocket. Each of these small rolls was painstakingly wrapped in cloth. His razor and the gold bridges were similarly done up before being stowed in his capacious pockets.

An examination of Johnson’s rifle revealed yet another grim bit of evidence that the fugitive had been determined not to come alive into the hands of the police. A loose butt plate on the weapon stirred the officers’ curiosity and they removed it. There, cunningly fitted into a niche bored in the wood of the stock, they found a single round of ammunition, carefully wrapped in cloth.

That round, Johnson had unquestionably saved for himself — if the worst came.

There was not a scrap of paper in Johnson’s pockets — not a line of writing that might have aided the police in backtracking along his sinister trail through the Territories and Yukon. This circumstance, too, inclined the police to the theory that Johnson was not the simple “bushed” trapper that he had purported to be.

It was at La Pierre House, too, that I learned of the circumstances which had turned Johnson back on his Eagle River trail and finally brought about the last battle with the avenging posse. We had been inclined the previous day to the theory that the fugitive had once more back tracked to protect himself; thus fallen a victim to his own cunning.

But Constable May, the officer from Old Crow, followed Johnson’s trail up the Eagle River after the fight. He found, at numerous places, indications that Johnson had mounted the steep river bank to watch his trail. Where he finally turned back, the fleeing man had climbed a tree to scan the river behind him.

My theory is that Johnson, while up this tree, caught sight of the dog teams coming up the river. But, confused by the windings of the stream, Johnson came to the conclusion that the posse was ahead of him instead of behind him. As a consequence, he came straight back to meet them. Only a man who has flown over the Eagle River and seen its maze of windings and turnings from the air could appreciate how easy it would have been to make this mistake. But it is my belief that that’s exactly what happened.

Our discussion of the previous day’s battle over, Inspector Eames informed me that he would fly back to Aklavik that day, taking Johnson’s body and kit with him. Jack and I loaded Johnson’s body, his face still distorted in that horrible sneer, into the Bellanca and hopped off for Aklavik. Our return flight was made without incident, and soon we were back at the police post and where the Inspector fingerprinted the dead man. That proved to be a horrible task, too, for Johnson’s body was frozen hard as iron and his hands clamped like claws as he had died clutching his rifle.

That horrible sneer was still on Johnson’s face the last time I saw him. I suppose they buried him that way. He’ll never change. The Arctic cold will keep that sneer unchanged throughout the centuries.

Johnson, as I saw him, was about 178 cm (5 ft. 9 in.) tall. He had exceptionally long arms, and very narrow hips for a man with his chest measurement. His ears, very prominent, were slightly deformed. His hair was far back on his forehead and he had a pug nose with large flaring nostrils.

Next day (February 22) as there was a shortage of supplies at Aklavik, I flew to Arctic Red River, at the junction of the Arctic Red and the Mackenzie, and brought back a load. The following day, my task completed in the North, I left for Fort McMurray. We brought constable King, who had recovered from his wound sufficiently to go “outside,” and constable Millen’s body with us. I was held up for one day by a storm at Fort Simpson on our trip out, and landed at our aerodrome on the river on February 24. It was three weeks to the day since we had left for the North.

I thought then that the end had been written to the Johnson case. But Johnson, his horrible sneer hidden in his grave at Aklavik, was fated still to provide the police with a puzzle. Today he is still as great a mystery as he was the day that he came floating down the Peel River on his log raft.

Early in the chase, when newspapers were blazoning the story of the Rat River hunt across North America, a prairie farmer “recognized” Johnson as an Albert Johnson whom he had known, and who was believed to be trapping in the North. Pictures of this Albert Johnson were reproduced in newspapers throughout the world, labelled as the desperate trapper of the Rat. Police and public, for the moment, were satisfied with that identification.

Then, one day, this Albert Johnson walked into the editorial offices of one of the Western Canadian newspapers which had used his picture, informed the perspiring editor that he was not the “mad trapper,” and that he was considering an action for damages against the publishers.

So the police were confronted once more with the puzzling question: Who was this man who, under the name of Albert Johnson, lay in a grave at Aklavik? Dead and buried, the mad trapper brought about a new hunt throughout North America as police officers, working with the prints of his frozen fingers, sought the answer to the puzzle.

Shortly after I returned from Aklavik I got the thrill of my life when I picked up a copy of True Detective Mysteries and started to read the stories. I came to one, written by Luke S. May, Seattle criminologist, on his chase through the craters of the Moon in Idaho on a hunt for coyote Bill. He was wanted for a hold-up and the murder of a man who was superintendent of an irrigation company in Idaho state. Staring at me from one of the pages was a picture of Coyote Bill.

I gazed at it for a moment, puzzled. Where, I thought, had I seen that face before? It certainly was familiar. Then there crashed back into my mind another face — a face contorted by a hideous sneer as it lay behind a bullet-riddled bed-roll on the ice floor of the Eagle River. The resemblance was striking — and I’m almost certain that Albert Johnson, the mad trapper of Rat River, will prove to be Coyote Bill, the man whom Luke May pursued through the far-off Craters of the Moon in Idaho, and finally was forced to abandon the search.

As I read Mr. May’s story, the resemblance between the two men became even more convincing. The Coyote Bill mentioned in his story was a trailsman skilled in every trick of the open spaces. He was a man of iron constitution, and he was reputed to be a deadly shot. Coyote Bill, too, had been a trapper in Idaho and Washington and, when his trail vanished in that state, it was believed that he had fled to Yukon, Alaska or the Canadian North.

Johnson, as we had known our “mad trapper,” undoubtedly came from Yukon. Mounted Police now believe that he came down the Yukon River and along the Tatonduk, a tributary that stretches eastward and whose headwaters rise just west of the divide where the Peel and the Porcupine Rivers originate. There isn’t the slightest question that Johnson had intended to go down the Porcupine, and thus penetrate the wild, inaccessible, sparsely-settled region in North Yukon where a man could live for years, alone and unrecognized.

What better haven could a man of coyote Bill’s type have desired — a trapper fleeing from civilization with a murder charge hanging over his head? And the description and characteristics — they fitted at every point!

But Fate — a Fate which Johnson cursed bitterly, you will recall, when he learned he was on the wrong stream — betrayed him into launching his raft on the Peel, instead of the Porcupine. This mistake was one which any man might have made, especially if he was unfamiliar with the country. A glance at the map will show that the Porcupine and Peel rise close to each other. As a result, instead of floating down the Porcupine into the absolute wilderness, Johnson came instead to the comparatively thickly settled district around Fort McPherson and the Rat River. This was country where trappers and Indians were numerous, and where the Mounted Police, deadly foes of lawbreakers, maintained several posts and kept in close touch by radio with far-off civilization. 80

This theory also explains, I believe, the mystery of that fortress cabin which Johnson built in his clearing on the Rat River, and which puzzled the police. It would explain the back-breaking toil which Johnson had undertaken to sink the floor below ground level, and it would explain the double-logged wall and the cunningly placed loopholes that commanded the clearing. Johnson was building, not a simple trapper’s cabin, but a fortress from which he could defy the police — if it became necessary.

I believe, too, this theory explains Johnson’s attitude toward friendly wilderness visitors who dropped into his camp on the Peel and his cabin on the Rat, only to be ordered brusquely, at the point of a gun to “keep agoin’.” Johnson, if he was Coyote Bill, wouldn’t want inquisitive trappers and Indians prying into his secrets.

It explains, I think, the lies which Johnson told Constable Millen on their first encounter in the autumn of 1931 in Fort McPherson, and his growled reply to the Mountie: “I don’t want to have anything to do with the police — there’s always trouble when they’re around.”

Johnson, a simple trapper, had no cause to fear the police. But Coyote Bill, with his picture and description and fingerprints on file with these self-same Mounties, would be very chary of meeting any police officers.

Now, if Johnson were Coyote Bill, with a murder on his conscience and a police officer hammering on his fortress door, what was more natural than to fire a treacherous shot through the door, as Johnson fired at Constable King? He would be desperate, cornered and ready to fight for his life — as Johnson obviously was.

There wasn’t a single logical reason to explain Johnson’s attack on Constable King. Up to the time that he fired that shot, Johnson had no reason to fear the police. The only reason that has ever been advanced for that murderous attack was that he was “bushed” — Arctic crazy. From my experiences in that chase, I’m convinced Johnson was anything but a lunatic.

Finally, I believe Johnson’s identification as Coyote Bill would solve the puzzle of the sawed-off shotgun, whose possession by the Rat River fugitive puzzled Inspector Eames. No Arctic trapper, “bushed” as Johnson was supposed to have been from years of loneliness in the North, would have thought of constructing such a murderous weapon. But Coyote Bill, crony of crooks in the underworld, would have been familiar with this deadly thugs’ weapon. He would have realized only too thoroughly its vicious advantages in a desperate battle at close range.

I’m pretty nearly certain in my own mind that Johnson, the mad trapper of the Rat River whom justice overtook on the icy bottom of the Eagle River, will prove to be Coyote Bill, the Idaho murderer who outfooted retribution in his dash through the Craters of the Moon.

Time — and the prints of Johnson’s frozen fingers — will eventually prove whether I am right.

(Editor’s Note: Despite Wop May’s web of strong circumstantial evidence linking Coyote Bill to Albert Johnson, the fingerprints did not match.

Police still do not have an answer to the question: Who was the Mad Trapper of Rat River?)