The Song of Roland displays the characteristics of a narrative type that I call “dual-focus.” The narrator follows no single character throughout but instead alternates regularly between two groups whose conflict provides the plot. Because the group rather than an individual plays the lead role, individuals serve primarily as placeholders, defined by the group, rather than as characters whose development constitutes an independent subject of interest. Succeeding following-units typically portray the two sides engaged in similar activities. This parallelism induces comparison of the two sides and is the source of the text’s main rhetorical thrust. Each new pair of following-units is related to the previous pair by the principle of replacement. The text’s structure resembles that of an equal-arm balance. When a member of one group changes sides or refuses to fight, the balance of power is destroyed and the plot is set in motion. The text ends when the two sides are reduced to one, by death or expulsion, or through marriage or conversion.

Within this basic pattern two separate but complementary models may be discerned. The first operates as if the two opposed groups carried the same magnetic charge. As the text progresses and the two sides come closer together, the group that is more firmly fixed repels the other from its field. Fixation is effected by the text’s rhetorical dimension, eliciting the reader’s sympathy for one side over the other. This pattern, which I call “dual-focus epic,” normally concludes with the elimination or containment of the side condemned by the text’s rhetoric. Many of the texts that display this pattern are popular in nature, ranging from the medieval popular epic to comic strips and science fiction, and from the Gothic novel and roman feuilleton to the Hollywood western. Other dual-focus epics are religious in nature, including major portions of the Old Testament, the New Testament book of Revelation (Apocalypse), Hesiod’s Theogony, and the Babylonian Genesis known as Enuma Elish. Wherever there is religion, there is of course parody, as evidenced by works as diverse as the early Batrachomyomachia (“Battle of the Frogs and Mice”), the Roman de Renart, the Renaissance mock epic, and Jonathan Swift’s Battle of the Books. Many texts that have normally been read, like Roland, as the stories of individual heroes, make more sense when they are returned to their rightful place in the dual-focus tradition. Later we shall have occasion to see why Homer’s Iliad and Vergil’s Aeneid should be placed among this number.

Dual-focus narrative is not restricted to literary texts. It extends to historical narratives like Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War, Tacitus’s account of the aftermath of Nero’s death in the first book of his History, and Augustine’s City of God, as well as historical fictions from Flaubert’s Salammbô to the films of Sergei Eisenstein. The cinema is a favorite medium for the development of dual-focus potential, in such films as D. W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation, Jean Renoir’s Grand Illusion, Luis Buñuel’s Viridiana, and scores of popular favorites like Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack’s King Kong, Cecil B. De Mille’s Unconquered, and Gordon Douglas’s Them! The plastic arts have also long borrowed the form and thematic concerns of dual-focus epic, from the high culture of Romanesque Last Judgment scenes to the commercial simplicity of magazine advertisements showing two washing machines and two equal-sized boxes of detergent, the lowly Brand X and the New! Improved! Will-get-your-clothes-one-hundred-percent-brighter Brand Y. In all these texts, irreducible differences place the two sides in opposition, creating pressure that ultimately leads to domination by one of the two groups.

Another group of texts, which I call “dual-focus pastoral,” shares almost all the characteristics of dual-focus epic. Dual-focus pastoral texts retain the alternating following-pattern and parallelism, group-conscious and apsychological characters, progression by replacement, and a plot that operates according to a balance mechanism, accompanied by the basic dual-focus tendency to suppress the temporal flow in favor of static spatial structures. The difference between the two forms stems from a simple shift in the relationship between the two mirror-image groups. If dual-focus epic sets one side against the other, like similarly charged magnets laying equivalent claims to the same space, dual-focus pastoral features magnets with opposite charges, two sides that seek union. Whether or not the primary identity of the two sides in dual-focus pastoral is sexual (as it usually is in Western literature), one side is almost always associated with a strong male factor, while the other is given a strong female identity. The union that brings the text to a close is thus assimilated to marriage, whether between individuals, families, countries, or philosophies. As in dual-focus epic, the two sides are ultimately reduced to one, that reduction marking the end of the text.

Like its epic counterpart, dual-focus pastoral proliferates in popular literature. From the Alexandrian romance as represented by Heliodorus’s Aethiopica or Longus’s Daphnis and Chloe, to a Renaissance pastoral novel like Honoré d’Urfé’s Astrée, all the way to the Hollywood musical, dual-focus pastoral has survived nearly unchanged. Western society has always found a place for this dual-focus complement to the more highly regarded epic form, as we see in the Old Testament books of Ruth and Song of Songs, medieval romances like Boccaccio’s Filostrato, Chrétien de Troyes’s Cligés, the Provençal Roman de Flamenca, or Aucassin et Nicolette’s clever parody, and modern love stories as diverse as Nathaniel Hawthorne’s House of Seven Gables and James Cameron’s Titanic. In fact, dual-focus pastoral has often been combined with dual-focus epic, as in the amorous diplomacy of Esther in the Bible, the Nibelungenlied, and Honoré de Balzac’s Les Chouans, or the thrills and then chills of Geoffrey Chaucer’s Troilus and Cressida, Robert Wise’s West Side Story, and Vittorio De Sica’s The Garden of the Finzi-Contini. The genre of melodrama in particular has shown a continuing capacity to merge the two forms, for the combination of a villain, a damsel in distress, and a dashing young savior offers a compact method of satisfying the needs of dual-focus epic and pastoral alike.

Let us begin with a metaphor, a touchstone to which we can return from time to time to validate our results: dual-focus narrative is a chess game, a balanced confrontation where the two sides move alternately according to a simple set of rules, each piece having a limited function meaningful only in terms of the larger fate of its side. The battle takes place in time, yet strategy must be conceived in space, the opponent’s position remaining fully as important as the attacker’s plans. How then does this game begin? What action must be performed in order for the match to start? White moves first, but much has taken place before White can advance the first pawn. Two actions precede White’s first move, and precede it they must, for without the chessboard and the pieces the competition cannot begin.

Two simple procedures characterize the creation of the dual-focus world. First, a contested space must be created, limited on all sides and clearly displaying its major axis of symmetry. What kind of a match would it be if the threatened pieces could simply maneuver off the board in order to escape the attack? Second, the players must be divided into two equivalent groups, clearly identifiable by a difference in color, uniform, language, sex, or other differentiation device. A football game begins in just this way. The day before, there were men all over the field, running this way and that, chaotic, helter-skelter, chasing passes onto the cinder track and errant kicks into the stands. The next morning, the groundskeepers appear, outlining the playing surface in bright white chalk. When game time arrives, the teams pour out of the chute onto the field, the home team clearly identified by its gold helmets and black uniforms, the visitors resplendent in their green and white. The game can now begin, because the formless mass of the day before has achieved differentiation through the magic effect of white lines and color-coded uniforms. The undefined, unbounded battleground has now been marked off and delimited, and the players’ allegiances identified.

Whatever their scope, dual-focus texts must effect this definition by differentiation. Exposition and creation thus become quite literally synonymous. Borrowing from an earlier tradition, the beginning of Ovid’s Metamorphoses neatly summarizes the doctrine of creation by separation with its implied parallels between God, the universe, and its elements on one side and the narrator, the text, and language on the other:

Before land was and sea—before air and sky

Arched over all, all Nature was all Chaos,

The rounded body of all things in one,

The living elements at war with lifelessness. . . .

No living creatures knew that land, that sea

Where heat fell against cold, cold against heat—

Roughness at war with smooth and wet with drought.

Things that gave way entered unyielding masses,

Heaviness fell into things that had no weight.

Then God or Nature calmed the elements:

Land fell away from sky and sea from land,

And aether drew away from cloud and rain. (1958:3)

The cosmogonic act creates a world and a language, but not just any world, not just any language. Both are built on the principle of binary opposition, so that the war of the words can adequately describe the battle of the elements, those of the text as well as those of the world.

If Ovid’s style depends on a series of oppositions, it is clearly because only a nominal, dichotomized style can properly evoke the world seen from a dual-focus perspective. When Augustine writes his Confessions, he evokes his past sins and shows by what actions, by what thoughts, he changed his life. He has no room for balanced opposition of noun to noun, of clause to clause, because the whole point of his account is to reveal not the static binary nature of the world but man’s opportunity for change. When Augustine turns to history, however, his style turns along with him. The City of God rewrites the history of mankind as the unceasing opposition between two cities. Consequently, its style appears to be generated by the simplest of computers, the use of any noun immediately calling forth its mirror-image counterpart. The City of God (but not The Confessions) clearly operates according to dual-focus principles.

The lexicon of dual-focus texts resembles that of our chess metaphor. The game cannot be played until and unless every “white bishop” is given a corresponding “black bishop.” Dual-focus vocabulary is thus double, containing both a parameter of comparison (“bishop”) and a uniform identifying allegiance (“white” or “black”). In fact, dual-focus vocabulary is doubly double. If the contrast between a white bishop and a black bishop activates the text’s axis of symmetry, the juxtaposition of a white bishop and a white king feeds the text’s integrative axis. This bipartite status of dual-focus words requires a two-part analytical process like that used above for The Song of Roland:

1. Organization of the text into pairs of actions, characters, or following-units defined according to the same parameter.

2. Comparison of the two elements in each pair in order to isolate the characteristics particular to each side.

As used by Ovid, “heat” and “cold” are not two different, independent words but the same word with opposite signs. To read these terms successfully, we need to recognize heat and cold not as separate terms but as the two parts of a dual concept, containing both a parameter of comparison (heat) and a marker of allegiance (the opposite plus and minus signs). Only in this way can we make sense of dual-focus narrative’s characteristic method of organizing texts and worlds.

In keeping with dual-focus modes of understanding, the Old Testament God is said to have created the elements not individually but in pairs. Darkness is not created, it is separated from light, thereby simultaneously constituting both paired elements. Woman is not created separately from man, she is separated wo-man, from man. Even the Jewish people are by no means created, in the modern sense of that word; instead, they are differentiated. Just as the Tower of Babel story explains the dispersion of a single language into many, the Genesis account of Adam’s descendants shows how a single family gave rise to many nations, with Israel in the center and its enemies in outlying lands. Out of sibling rivalry situations, Genesis generates the foes that plague Israel throughout the Old Testament. From the line of Cain come the herdsmen who live in tents, those who have no fixed home. Ham, who gazed on his father’s nakedness, gives rise to a long list of Israel’s traditional enemies, including the Babylonians, Egyptians, Assyrians, and Philistines. Lot, Abraham’s nephew who slept with his daughters, is the father of the Moabites and Ammonites. The Edomites descend from Esau, whose intermarriage with foreigners suggests that he “despised his birthright” long before he was formally robbed of it by a conspiracy of his mother and younger brother, Jacob. Only with the reunion of Joseph and his would-be fratricidal brothers at the end of Genesis does the pattern of sibling rivalry cease, now that the Israelites and their enemies are well defined. This separation stage reaches its culmination at the beginning of Exodus with the Passover, reaffirming separation of the world into Jew and non-Jew.

The subsequent giving of the law to Moses on Mount Sinai thus entails little new material. It is simply a recognition of already established principles, a codification of the reasoning behind the previous differentiation of the world into two radically different groups and value systems. Cain set himself before God (“You shall have no other gods before me”), and so killed his righteous brother (“You shall not kill”). Ham committed an act of perversion with his sleeping father (“Honor your father and your mother”). Joseph’s brothers were envious of his privileged position in the family circle, and so they sold him into slavery (“You shall not covet”). And so on. Once the Chosen People have reached the Promised Land, the chess game can begin, for Genesis has provided not an undifferentiated world equally available to all but a carefully laid out playing field with a set of mirror-image players, and Exodus has codified the rules by which the game is to be played. The rest of the Old Testament reads like a list of permutations generated by this junction of a series of enemies and a list of laws.

As the Old Testament establishment of the Law clearly reveals, one of the most important aspects of dual-focus narrative is the development of a language suited to description of the text. The binary opposition of Cain to Abel, of Lot to Abraham, of Esau to Jacob, and so forth not only splits the world into separate groups but also provides new vocabulary with every division, new terms particularly appropriate to the text’s dual-focus world. Just as the arrangement of chessmen on the chessboard identifies white versus black as a meaningful opposition, so the division of Noah’s sons into Ham versus Shem and Japheth defines “Honor your father” versus “Shame your father” as a meaningful opposition and thus as an important critical tool. Dual-focus texts require readers to remember the differences established in the exposition and to use them as critical vocabulary.

Less formulaic in style and structure than sacred texts, dual-focus novels often delay presentation of their constitutive dualities until the reader has already become familiar with the characters and their contexts. Émile Zola’s Le Ventre de Paris thus remains, for half of its length, a very confusing novel indeed. Florent, whom we expect to become the main character of a typical biographically shaped novel, has just returned from political prison in Cayenne. He moves in with his sausage-making half-brother, finds a job supervising the sale of fish in the central Paris market, and in general serves as our eyes, nose, mouth, and ears as Zola introduces us to the belly of Paris, its delights and excesses. We learn about the operation of Les Halles and the life of its denizens, but we remain in doubt about the novel’s direction. Florent has a few quarrels, makes a friend or two, perhaps even falls in love, but we are never sure because we enjoy no interior views of his personal desires or his revolutionary plotting.

In the absence of a clear sense of the novel’s structure we have no idea what to look for. For us the text remains chaotic, just as the market does for Florent, until he leaves the city with his friend Claude. During their excursion to Nanterre (then a garden spot well outside of town), Claude explains the world to Florent. The market runs not according to a set of laws handed down by the government, says Claude, but according to one of the oldest laws in the universe, the war between the Fat and the Thin (whence the novel’s usual English title). Suddenly, the people and smells, places and sounds, tastes and animosities of Les Halles come into sharp focus. For fully half the novel we had floundered in the watery confusion of the fish market and lingered without obvious purpose among the fattening delights of the pork butcher’s shop, café-hopping like a Parisian student unsure how to organize his day. Before, we had been vaguely following Florent, though by no means continuously. Now that the text has received definition, now that we have a vocabulary for ordering the many sensations that the text provides, the following-pattern as well becomes more clearly defined. From now on the text’s dual-focus status becomes apparent, with regular alternation and opposition between two camps, the Fat and the Thin.

What Zola holds off until the middle of Le Ventre de Paris, the cinema often provides in a film’s opening footage. Around the time of World War I, movie houses didn’t wait even that long. A melodrama might be introduced in such a fashion as to leave little doubt about the necessary critical vocabulary:

You may

Applaud the Hero

and

Hiss the Villain

Defining the owner’s expectations regarding the conduct and class of the audience, lantern slides often preceded the show, displaying a message like this:

Gentlemen will please remove their hats, others must

In much the same way, dual-focus films sometimes organize the credits preceding the action not in order of the actors’ appearance but according to their distribution within the film. Charlie Chaplin’s Great Dictator, for example, arranges the credits in two separate but parallel lists: “People of the Palace” and “People of the Ghetto.”

Whereas literature exists only in time, placing each word after the preceding one, cinema has the ability to work in space as well, thereby gaining an additional method of dividing the world. Alfred Hitchcock’s Notorious is one of many films that opens on a trial scene viewed from a doorway at the back of the courtroom, with the camera carefully stationed right on the room’s axis of symmetry. The center line of the frame thus corresponds exactly to the center line of the courtroom, both real and filmic space thus being exactly split between the accused German traitor and the U.S. prosecutor. The opening frames of Vittorio De Sica’s Garden of the Finzi-Contini introduce a bevy of white-shirted bicyclists intent on traversing a high, solid, stone wall in order to reach the object of their summer joy, a tennis court, on the other side. We have so little idea who these young people are that we concentrate instead on the battle with the wall. There, as they stand dejectedly in the street, our eyes and our sensitivities are trained to see the world as space, divided by the walls of social distinction. Within lies the private domain of the Finzi-Contini, Ferrara’s most powerful family, while on the outside waits youth, powerless until it has been recognized by the Cerberus who eventually opens the gate. Before characters even have names, De Sica’s clever exposition implies, they are defined by the space they inhabit and the walls that bound them.

Even when cinema works sequentially, it often provides spatial definition for dual-focus films. Once Jean Renoir has shown us the French officers’ quarters in the opening scene of Grand Illusion, he rapidly provides a parallel scene identifying the stakes of the initial scene. After Maréchal (Jean Gabin) and de Boeldieu (Pierre Fresnay) have been shot down, they are brought to the German headquarters commanded by von Rauffenstein (Erich von Stroheim). In many ways the two places are similar: on both sides there is music, drinking, and talk of women. Temporary army camps, we easily imagine, cannot differ much from one side of the line to the other. And yet there are differences. The French soldiers listen to a popular song and babble on in familiar language about the squadron’s shared girlfriend, while in the German camp we hear a Strauss waltz and multilingual conversation about the capitals of the world. Renoir goes beyond national difference—the expected parameter of opposition in a war film—to redefine the French camp as common and the German camp as aristocratic. In this masterful movie where the popular/aristocratic dichotomy slowly replaces the French/German clash, Renoir has from the very beginning provided the two vocabularies necessary for analysis of the film.

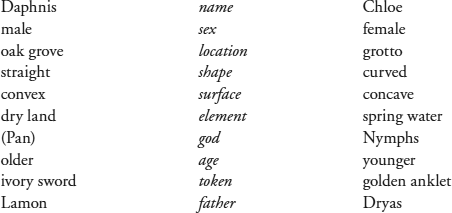

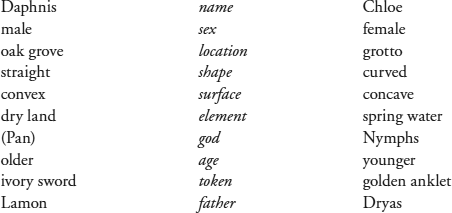

Dual-focus pastoral operates in much the same way, deploying the same techniques of thematic, linguistic, and character differentiation used in its epic counterpart. At once the most naïve and the most sophisticated of the Alexandrian romances, Longus’s Daphnis and Chloe goes Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones one better. “Two Foundlings,” it might be called, for the text begins with parallel discoveries. Daphnis is found in the woods, being nursed by a goat. Chloe is discovered in the grotto of the nymphs, where a ewe gives her suck. The most obvious opposition emphasized by these paragraphs is the male/female difference, for Daphnis and Chloe is the story of the two foundlings’ accession to the sexual knowledge of their parents’ generation, but readers who see no more than a biological opposition in these opposed paragraphs are missing a chance to learn how to read the text. Dual-focus expositions offer a lesson in critical approaches in addition to introduction of the dramatis personae. Just as the Old Testament’s meaning is implicit in the divisions highlighted by sibling rivalry (Chosen People/others, Promised Land/periphery, virtue/vice), so the opening paragraphs of Daphnis and Chloe provide the tale’s basic differences and parameters, as represented in fig. 3.1. Every opposition, however simple, eventually plays a part in Longus’s story. With no further information than that provided by the distance separating the opening paragraphs, we can proceed to a clear understanding of Daphnis’s and Chloe’s sexual strivings.

Hawthorne handles the problem of dual-focus pastoral exposition quite differently in his House of Seven Gables. Instead of introducing the pair of young people who will provide the novel’s love interest, he begins with Colonel Pyncheon’s illegitimate bid to snatch a plot of land from Matthew Maule, its rightful owner. On the one hand, a colonel, a man of the sword; on the other hand, a carpenter named after an apostle. Soon the two families laying claim to the same land achieve increasing diffentiation. The new house on “Maule’s Lane, or Pyncheon Street, as it were now more decorous to call it” (1851:18) may belong to the Pyncheon clan, but it is built by a Maule, thus perpetuating their claim to an interest in the property. Even after the Maules seem to have abandoned hope, the two families’ parallel claims continue to retain the narrator’s attention. The Pyncheon approach to the problem of real estate is typically feudal and aristocratic, based “on the strength of mouldy parchments,” while the Maules know no other claim than “their own sturdy toil” (26), the method of a new class whose development in this country was an item of keen interest to Hawthorne. The well of nobility has run dry, he implies, just as the Maule well, its water once so sweet and plentiful, went sour the day that the Pyncheons took over. All this took place many generations before Hawthorne’s narrative begins, yet the effects of the original distinction between Pyncheon and Maule linger on, informing the plot until such time as the two families can become reunited once again, through the romance of Phoebe Pyncheon and Holgrave the daguerrotypist. Just as Longus uses a dual exposition to associate his two foundlings with differences that will be essential to the remainder of the story, Hawthorne succeeds in making his young lovers carry important thematic baggage by beginning with the quarrel between their ancestors.

FIGURE 3.1 Initial oppositions in Daphnis and Chloe

The Hollywood musical often goes to great lengths to establish parallelism between male and female principals. MGM’s 1940 version of New Moon (directed by Robert Leonard) begins with two simultaneous shipboard songs. On deck, Jeanette MacDonald sings in the elegant garb of the aristocracy. Cut to Nelson Eddy, singing behind bars in the hold. Just as The Song of Roland reinforces parallels by the use of repeated formulaic language, so New Moon draws the two songs together by using the same editing sequence for both stars, with similar shot changes punctuating the lyrics at exactly the same spots for both renditions. But paired songs need not be simultaneous or similarly edited if they display parallel concerns. After Maurice Chevalier’s opening praise of “Little Girls” in Gigi, director Vincente Minnelli offers us a diptych of songs that create a connection between Gigi (Leslie Caron) and Gaston (Louis Jourdan) even before we see them together. Once Gigi has expressed her frustration with Paris life in “I Don’t Understand the Parisians,” Gaston’s “It’s a Bore” gives voice to a similar displeasure with life in the French capital. Virtually any aspect of a film can be used to establish parallelism between the male and female leads. In Thornton Freeland’s Flying Down to Rio, back-to-back writing desks and paired cables establish the parallelism between Gene Raymond and Dolores del Rio. In W. S. Van Dyke’s Sweethearts and Minnelli’s The Band Wagon, mirror-image sets are used to reinforce the Eddy-MacDonald and Astaire-Charisse contrast.

Whether epic or pastoral, dual-focus texts systematically present their action as generated by preexisting categories. Exposition of those categories thus takes on enormous importance, for it is only through connection of individual characters to long-established groups and values that dual-focus narrative can operate. This is why so many dual-focus texts begin in medias res, stressing a constitutive conflict or difference even before we meet the characters involved. In many cases, the background of the main characters is withheld until the dual-focus parameters are set. Not until Superman has had the opportunity to bring many criminals to justice do we learn the story of his birth, and then only as an explanation of his sensitivity to kryptonite. In The Song of Roland we learn of Roland’s prowess in fighting the Saracens, but only in later epics do we learn about his childhood and early exploits. As the alternating following-pattern clearly reveals, dual-focus texts are not about personal growth and decisions but about the differences between categories and the characters or groups that embody them.

Dual-focus exposition characteristically involves creation of an entire universe—not just two opposed camps and the world around them but also the language necessary to describe that world. Unable to exercise personal control over their surroundings, dual-focus heroes at best understand the laws that govern their world and act accordingly, thereby attracting to themselves the adjectives that identify the elect in the linguistic system imposed by the narrator. Dual-focus characters are part of the created world; they cannot escape their position. Nor can they, like a picaresque protagonist oppressed by this week’s master, simply walk out and create a new universe. The dual-focus world is finite, with laws and language delineated from the outset.

Chess players derive a certain thrill from knowing that their resources are limited and that neither the rules nor the board can be stretched. The winning strategy is not to expand capabilities, as one of my childhood opponents used to do by slipping an extra piece on the board when I was looking elsewhere, but to maximize efficiency with the available resources. A black bishop is a black bishop; it cannot become a white one. The words black and white are not available for transfer in the chess text as scared and courageous are in Stephen Crane’s Red Badge of Courage. Whatever Jean-Paul Sartre may say, in the dual-focus world essence precedes existence. To understand the role that language plays in this system, we can do no better than to meditate on Isabel MacCaffrey’s pertinent remarks about Paradise Lost: “Milton makes his words take sides; the objects of the poem, both animate and inanimate, along with other names, are aligned in opposing ranks and forced to participate in the War in Heaven that is being continued on earth” (1959:101). In this section I examine the diverse methods employed by dual-focus narrators to make “words take sides,” thereby revealing the dynamics—or rather statics—of dual-focus opposition.

Of all our critical terms, perhaps the most problematic is the term “hero.” Because it combines affective and formal implications, the designation “hero” often implies more than is meant. While neologisms like “protagonist” and “antihero” facilitate reference to central characters who are not necessarily heroic, they provide little help with the inverse situation, the heroic character who is not necessarily central but who by virtue of heroic action is often assumed to occupy a central position. As with “character,” problems associated with the term and concept of “hero” have been largely neglected by critics and theorists alike (though see Mieke Bal’s lucid pages in Narratology on “The Problem of the Hero,” 1985:91–93).

Perhaps the most common result of this terminological quandary is the sort to which The Aeneid has regularly been subjected. Traditional criticism has treated Vergil’s epic as the story of Aeneas, the hero of Rome’s founding, the symbol of Roman power, and the classic example of Roman virtue. The first six books, in this traditional view, correspond to the wanderings of Odysseus, while the last six derive from The Iliad. Yet critics acknowledge that Aeneas is neither the instigator of the plot nor an individual independent of his exemplary status, nor even a character altogether capable of self-definition. In short, Aeneas corresponds to the affective content of our term “hero” but not to any of its structural implications. He is emphatically not followed throughout most of The Aeneid. Not only does he share the following-pattern with Dido and Carthage, as well as with Turnus and the Italians, but equal time is also given to the gods and their quarrels.

Aeneas is a hero, no doubt, but not because he is an individual. Instead of becoming a hero, Aeneas is born one. His very existence is predicated on his ability to represent exemplary Roman traits. In one sense, Aeneas is not a character in the traditional sense at all but a synecdoche, a figure representing in miniature, on a human scale, the secrets of Roman power and domination over the rest of the world. Because it is the literary property of the Roman cause, Aeneas’s character is not available to Aeneas to be defined through his own actions. Aeneas cannot create himself, because he has already been defined by his function. Aeneas is a hero all right, but in the dual-focus sense of that term. He is the group personified.

From the very exposition of The Aeneid, the dualistic nature of Vergil’s epic is apparent. As in The Song of Roland, the very first line introduces to us the man with whom the book closes, but once again that man is left behind before we have read ten lines, ceding his place to the one enemy who stands between him and his home. For it is the goddess Juno who first merits the narrator’s full attention. Not until all her quarrels are exposed, along with her support of the Greeks against the Trojans and of Carthage against Latium, does the narrator bring us back to Aeneas. By this time the design is clear: Aeneas will be constantly buffeted by all the storms that Juno can send to force him off his course or delay him. Dido and Turnus, Aeolus and Allecto may be only temporarily opposed to Aeneas, but Juno always is. Traditional criticism considers that The Aeneid belongs entirely to one character, yet the following-pattern constantly pairs Aeneas with a matching lover or a comparable combatant.

Only within the last half-century has The Aeneid’s dualism been recognized. Emphasizing the “great conflict throughout the whole poem between light and darkness” (1962:171), Viktor Pöschl has masterfully analyzed the manner in which Vergil subjects the structure of his epic to tension between two fundamental forces:

Vergil’s Jupiter is the symbol of what Rome as an idea embodied. While Juno as the divine symbol of the demonic forces of violence and destruction does not hesitate to call up the spirits of the nether world . . . Jupiter is the organizing power that restrains those forces. Thus, on a deeper level, the contrast between the two highest divinities is symbolic of the ambivalence in history and human nature. It is a symbol, too, of the struggle between light and darkness, mind and emotion, order and chaos, which incessantly pervades the cosmos, the soul, and politics. . . . The struggle and final victory of order—this subduing of the demonic which is the basic theme of the poem, appears and reappears in many variations. The demonic appears in history as civil or foreign war, in the soul as passion, and in nature as death and destruction. Jupiter, Aeneas, and Augustus are its conquerors, while Juno, Dido, Turnus, and Antony are its conquered representatives. The contrast between Jupiter’s powerful composure and Juno’s confused passion reappears in the contrast between Aeneas and Dido and between Aeneas and Turnus. The Roman god, the Roman hero, and the Roman emperor are incarnations of the same idea. (17–18)

One of the leitmotifs of Pöschl’s study is Goethe’s insistence, expressed in a letter to Friedrich Schiller (8 April 1797), that each scene must symbolically represent the whole. It is precisely The Aeneid ’s dual-focus structure that permits Vergil to follow this precept so scrupulously. Just as the exposition must be double, so every part of the work depends on the alternating following-pattern’s constant invitation to compare and contrast the juxtaposed parties. If Aeneas’s wanderings are relegated to an included story, it is not solely to permit the book to begin in medias res but also to avoid giving the impression that Aeneas himself is the poem’s subject, he must not be made to appear so. Even Aeneas’s final victory shows him as part of a diptych, his patience and humanity opposed to Turnus’s irrational anger and barbarism. Like other early epics that show Moses and the Israelites fleeing from Pharaoh or the Greeks laying siege to Troy, The Aeneid portrays a battle between continents, a fight reminiscent of the wars that pitted Hannibal’s elephants against the ordered legions of the Imperial Army. Vergil’s universe is clearly that of the concentrically organized Old Testament, for the true antonym of “Citizen of Rome” is not “Citizen of Carthage” but “barbarian.” Those who enjoy Roman citizenship have all the rights of the world’s most powerful, most civilized nation; outsiders have none. Ingroup, outgroup—always the spatial distinction of a line drawn around the group in order to distinguish inclusion from exclusion. Those Italians who are willing to accept peaceful cohabitation may perhaps gain the advantages of citizenship, but the shameless fornication of a Dido or the barbaric fighting style of a Turnus must forever exclude them.

To emphasize citizenship is to play up the importance of foundation, whether of Rome in The Aeneid, the Promised Land in the Old Testament, or socialist Russia in Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin. Foundation of a still existent state—along with worship of the founders—offers a theme that effectively reinforces audience homogeneity. Dual-focus narrative creates continuity between the distant past and the living present by means of a series of replacement operations. Just as Latium will be the new Troy, Augustus will be a scion of Aeneas’s line. Even when the relationship is more or less facetious, as in René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo’s comic strip Astérix le Gaulois, the continuity from text to audience is immediately apparent. Vergil affords readers every opportunity to identify with individual characters, to participate in their dilemmas, and to learn from their reactions, yet the overall structure of The Aeneid calls for group reaction rather than individual identification. Because the text is about Rome rather than any particular individual, it might manage without Aeneas, but it cannot dispense with some sequence of circumstances leading to the founding of Rome.

Interestingly, when the classical epic sought a method of increasing psychological interest, the approach adopted remained decidedly dual-focus. Instead of following a single character exclusively, concentrating all attention on his motivations and decisions, the Christian writer Prudentius introduced a measure of psychological complexity into his Psychomachia, some four centuries after Vergil, by transferring The Aeneid ’s successive diptychs into the theater of the mind. Whereas character traits are always externalized in Vergil’s epic, with one set of attitudes attributed to Aeneas and another to his successive foes, Prudentius begins the long process of internalizing character psychology, using Virtues and Vices as his warriors and psychological allegory as his mode. In many ways—obvious to anyone who has read both texts—Prudentius is an inferior writer to Vergil, yet to Prudentius goes the credit for discovering an influential method of bending dual-focus strategies to psychological purpose. Nearly forgotten, Psychomachia deserves revival, for together with Augustine’s City of God it provided the foundation for a thousand years of medieval dual-focus narrative, in the visual arts as well as in literary, religious, and historical texts.

Prudentius’s text is built around seven hand-to-hand combats between Virtues and Vices, resulting in peace and the building of a new temple. Just as the Decalogue in Exodus renders explicit the dualities of Genesis, detailing the markers that distinguish Jew from non-Jew, so Prudentius codifies much of the Vergilian material. At the same time, he draws heavily on Old Testament parallels, thus effecting one of the first important syntheses of classical and Judeo-Christian dual-focus narrative. The second combat, in which Chastity meets Lust (Libido), clearly parallels the Aeneas-Dido relationship, for Juno’s strategy involved throwing Dido soul and body at Aeneas. The next fight presents the outcome of the Dido-Aeneas relationship, with Long-suffering (Patientia) battling Wrath (Ira). Like Dido, frustrated at her inability to debauch her counterpart, Ira eventually runs herself through with a sword. The rest of Prudentius’s epic operates in much the same way. Virtues named Lowliness (Humilitas), Soberness (Sobrietas), and Reason (Ratio) match Aeneas’s pietas, while Vices identified as Pride (Superbia), Indulgence (Luxuria), and Greed (Avaritia) neatly sum up the barbarism of Turnus and his allies Camilla, Mezentius, and Juno. The end of Psychomachia offers additional parallels to the founding of Rome. Just as Concordia sets foot inside the new temple, she is attacked from within by Discordia—an obvious reference to Roman mythology and the well-known sibling rivalry between Romulus and Remus.

On the surface, Psychomachia seems no more than a militant Christian text, with no explicit reference to The Aeneid. The examples cited are not classical but traditional Old Testament types: Job and Solomon, Judith and Holofernes, David and Goliath. Yet the choice and order of Virtues and Vices reveal the extent to which Psychomachia offers a psychological codification of Vergil’s epic. By combining classical and Christian psychology, Prudentius solved one of the Renaissance’s thorniest problems well over a millennium too soon. By using psychological labels and by making the human mind the battleground of his epic, Prudentius began a progression whose implications lead directly out of the dual-focus mode.

Dual-focus epic, as exemplified by the Old Testament, The Aeneid, and Psychomachia, operates according to what we might call “concentric dualism.” Value is allocated to opposed groups differentially, as if one group were nearer to the source of value than the other. Geography is thus always hierarchical in nature. Those closest to the center are valued most highly, for in the center is Jerusalem, the Temple, the Ark of the Covenant. In the words of Mircea Eliade (1959), the Promised Land is cosmos, the outlying regions chaos, and Jerusalem the axis mundi. Surprisingly, dual-focus pastoral often follows the same model. Though some dual-focus pastorals (such as Daphnis and Chloe) approximate equal treatment of male and female, thereby approaching a more egalitarian diametrical dualism, the more common method involves a sense of underlying inequality—of concentric dualism—as if dual-focus pastoral were simply a disguised version of dual-focus epic.

Because courtship is regularly treated as conquest in Western literature, women are repeatedly identified with territory to be occupied and won. Having conquered Italy, Aeneas simultaneously lays claim to the land and to the local king’s daughter, Lavinia. By concentrating attention on the clash between the villain and the young lover, popular melodramas effectively conceal the lover’s interest in occupying the young lady’s property. Though Hollywood musicals typically end with a marriage of apparent equals, closer scrutiny often reveals a substantial imbalance in the couple, almost always to the benefit of the man and the detriment of the woman. From Maurice Chevalier and Fred Astaire to Gene Kelly and Elvis Presley, the guy typically gets top billing and the better half of the deal. In Fred Zinneman’s Oklahoma!, Laurie may realize her dreams by marrying Curly, but when the cowhand weds the farmgirl he acquires her farm as well.

Daphnis and Chloe offers not only one of the most charming of all dual-focus pastorals but a myth of artistic interpretation as well. Longus reveals characters in the very act of learning that the world can be understood only in terms of a binary principle. At first, lacking knowledge, Daphnis and Chloe gather none of the fruits of their love. Only after the facts of life are passed on to them by nature and their elders will the two star-crossed lovers enjoy physical lovemaking. The overall pattern of replacement operations is typical of dual-focus pastoral: by marrying, children of different families gain the right to engender and raise their own family, thereby constituting a new generation. This saga of birth and repopulation reverses the epic tale of death and destruction, the two forms fitting neatly together as part of the larger dual-focus vision. At first nourished by goat and sheep, Longus’s pastoral pair are soon discovered by parallel peasant families, then eventually passed on to their rediscovered aristocratic parents. This series of parental replacement operations is not complete until the children born to the newlyweds are, in turn, confided to the care of a goat and a ewe. In this cyclical arrangement, the only change that takes place over the course of the text is replacement of one generation by its successor.

For that change to come about, however, Daphnis and Chloe must learn what the previous generation already knows. Taking his thematic material from the text’s fundamental male/female distinction, Longus portrays a boy and a girl learning what those sexual designations mean. For children to become parents, they must first learn to understand and to represent their sex. Since the cyclical nature of human existence depends on sexual categories, Daphnis and Chloe must learn to be defined by those categories in much the same way that Esther must accept and reveal her Jewishness or Aeneas his Roman virtue. Daphnis’s and Chloe’s new knowledge represents the actualization of a natural reality rather than the kind of learning associated with traditional definitions of narrative. Instead of becoming something that they previously were not, they move closer and closer to perfect representation of their divine archetypes: Pan, whose altar is by a tree (the masculine principle), and the Nymphs, who are worshiped in a grotto (the female principle).

Daphnis and Chloe exist in a world apart, a domain where the gods, people, and nature live in perfect concord, for the gods are the shepherds’ foster parents, and the animals their charges and constant companions. As long as the young lovers remain within this context the following-pattern strictly obeys the principle of alternation between male and female, goat and sheep. Protected by its peaceful isolation, this pastoral society is nevertheless not totally shut off from the outside world. At regular intervals, the calm and naïveté of pastoral seclusion are interrupted by incursions from the world of experience and violence beyond. Dual-focus pastoral alternation between Daphnis and Chloe thus shares the text with dual-focus epic alternation and conflict between the pastoral society and its less peaceful neighbors. Outside intervention is necessary because Longus’s shepherds are doomed to perpetual ignorance as long as they remain isolated. They try to imitate the lovemaking of sheep and goats, but they soon find it unsuitable for humans.

In lovemaking there is also an element of violence, Daphnis discovers to his horror. From the start, the violent outside world is defined as the erotic realm of the wolf. When Daphnis and Chloe take their herds out to pasture, “Eros contrived trouble for them. A she-wolf from the adjoining countryside harried the flocks” (1953:7). Only when Daphnis has himself fallen into the trap set for the wolf will he bathe himself before Chloe, thus lighting in her the low fire of young love. The flames are fanned as Dorcon, an experienced cowherd “who knew not only the name but the facts of love” (10), challenges Daphnis to a contest, resulting in a first kiss between the two foundlings. Daphnis then for the first time finds Chloe beautiful. When autumn comes, Daphnis is carried off by pirates, then is carried away by a view of Chloe’s naked body as she bathes to celebrate his return: “That bath seemed to him to be a more fearful thing than the sea” (18). But the young lovers cannot satisfy their longings without the good offices of Lykainion (whose name means “the little wolf”), a city wench who has long had her eyes on Daphnis. Knowledge gained outside the pastoral world turns out to be required for procreation of life within pastoral bounds. Daphnis and Chloe must learn the lesson of Eros: they must capture the wolf instinct and turn it to their own purpose. In the words of Paul Turner, “they cannot become mature human beings until they have come to terms with the ‘wolf ’ element in human nature” (1968:21).

Before they can come to terms with Eros, however, they must learn to interpret their world. Like the reader faced with the hidden pattern of a book, Daphnis and Chloe can make no progress in their understanding of the world until they discover its organizing principles. Nature is the text, Daphnis and Chloe are its readers. Progressively, the lovers perform for us the task of elucidating the text’s polarity adjustment process. Not until Daphnis first bathes himself before Chloe does she discover beauty. Delightfully naïve, she sets out to answer a simple question: What produces beauty? Daphnis bathed and he was beautiful, she thinks; perhaps if I bathe myself I too will be beautiful. But her bath changes nothing. When Daphnis pipes, that too makes him beautiful in her eyes; but when she pipes, it is to no avail. Action, Chloe discovers, is not essential but incidental, a hypothesis that she proves by her ineffectual metaphorizing:

I am sick for sure, but what the malady is I do not know. I am in pain, but can find no bruise. I am distressed, yet none of my sheep is missing. I feel a burning, yet am sitting in thick shade. How many times have I been pricked by brambles, yet I never cried; how many times have bees stung me, but I never lost my appetite. The thing that pricks my heart now is sharper than those. Daphnis is beautiful, but so are the flowers; his pipe makes fine music, but so does the nightingale—but flowers and nightingales do not disturb me. Would I could become a pipe, so that he might breathe upon me, a goat, that I might graze in his care! Only Daphnis did you make beautiful; my bathing was useless. (1953:9)

Daphnis fares no better when Chloe’s first nude bath leads him to discover beauty. At first, these would-be lovers mistakenly assume that all texts are the same, that each one can be compared to all the others without any loss of meaning. “They wanted something, but knew not what” (13).

What they lack is a clear understanding of the differences between their two bodies. In the dual-focus pastoral world it is difference, not change, that carries meaning. Like Montessori pupils, Daphnis and Chloe must learn to grasp the relationship between the peg and the pegboard, matching similar shapes and noting the difference between convex and concave configurations. If the young inhabitants of the pastoral world are slow to learn how their bodies differ, it is in part because those who have already discovered Eros take this knowledge for granted. Philetas thinks he is teaching them how to requite their love by suggesting “kisses and embraces and lying together with naked bodies” (1953:22), but he has left out the essential fact. He treats the young lovers as if they were both the same, as if they were exact mirror images one of the other. When Daphnis lies with Lykainion, however, he discovers the small but all-important flaw in the mirror. Chloe resembles him in all ways but one, he learns. Finally, in this binary principle, he gains the knowledge needed to read the world.

But Lykainion’s warning about the violence of lovemaking keeps Daphnis from running to Chloe and putting his newfound knowledge into practice. Just as the pastoral world cannot be self-perpetuating without letting a bit of Eros through a break in its walls, so Daphnis cannot make love to Chloe without causing her to bleed: “Chloe would soon have become a woman if the matter of the blood had not terrified Daphnis” (1953:46). Never, in the course of Longus’s tale, does Daphnis resign himself in a psychologically motivated manner to the “matter of the blood.” Instead, Longus handles the problem ritually, exploiting the divine affinities apparent since the story’s opening paragraph. At first goat and sheep, Daphnis and Chloe adjust to their roles as man and woman in two different ways. After learning a lesson in human anatomy, they perform the myths in which Pan enacts his sexual role with the Nymphs. When Daphnis’s foster father Lamon passes down the knowledge of his generation in the form of the Pan-Syrinx story, the two youths act out the tale, thus rendering explicit their relationship to Pan and Syrinx. Pan tried to persuade Syrinx to give in to his desires, but Syrinx refused a partially human lover. Hiding among the reeds, Syrinx was soon accidentally cut down by Pan. When he realized what he had done, Pan bound the reeds together, thereby inventing the flute. This etiological account reveals that lovemaking does indeed have a bestial element, while recognizing that beauty and music owe their very existence to the deflowering of a woman. The lesson is clear: for love to be requited, man’s bestial side must tear woman apart.

Once Daphnis learns this lesson he does his best to convey it to Chloe through another story about Pan. This time the goat god is courting the nymph Echo, who “avoided all males, whether human or divine, for she loved maidenhood” (1953:45). It would have been better for her, though, had she surrendered to Pan, for out of jealousy he tore her limb from limb and scattered her all over the land. And so it is, explains Daphnis, that today she returns our music like some antiphonal chant. Remembering the time when he and Chloe had competed verbally, alternately launching sallies “antiphonally . . . like an echo” (40), Daphnis expects Chloe to understand the parallel between their own situation and the story of Echo. Indeed, the Echo myth elegantly demonstrates the functioning of the flaw in the dual-focus mirror. Pan with his pipe makes sounds, but their beauty is complete only when Echo has responded with her chorus. The two are complementary, but different—Pan is the phallus, with his pipe, while Echo is the concave circle of hills that returns Pan’s compliment.

As recounted in Daphnis and Chloe, the Echo myth aptly describes more than just a single pastoral pair. For the antiphonal method is the basic mode not only of pastoral but also of dual-focus narrative as a whole. From Theocritus to Vergil and on to the Italian Renaissance, “amoebic” verse is the fundamental medium of the pastoral experience. Whether between two shepherds in a singing match or two lovers competing in fun against each other, the basic principle of this type of verse is contained in its name: amoibé or change. The formal similarities of succeeding verses create a mirror effect, but the amoebic aspect of the verse introduces the mirror’s flaw. It is instructive to compare the type of change inherent in amoebic verse to the type we associate with the novel of education. The novel portrays a character moving through time, changing as she goes, generating the text’s structure, which becomes increasingly based on change-over-time as the text progresses. In amoebic verse the situation is radically different, dependent instead on difference-over-space. The amoibé occurs not between one time and the next but between one character and another. Daphnis and Chloe may make significant progress in terms of their own personal education, but the text as a whole deemphasizes that progress in two distinct ways: the one cyclical (the end repeats the beginning), the other amoebic (constantly measuring the difference between Daphnis and Chloe rather than between one situation and the next). Interest is thus transferred from diachronic movement to the text’s synchronic dimension. We measure change not along the text’s temporal axis, as in the Bildungsroman (from ignorance to experience, for example), but at right angles to that temporal development.

From the formulaic repetitions of The Song of Roland to the antiphonal duets of the Hollywood musical, dual-focus narrative rejects change-over-time in favor of the amoebic principle of difference-over-space. What makes it so easy to construct comparisons is the formulaic nature of the fundamental distinctions around which dual-focus texts are built. In one sense, dual-focus characters don’t even have names—they are defined instead by their position. The name “Satan” means opponent, as does the Old French equivalent, averser, used throughout The Song of Roland. Even the word “enemy” is none other than in plus amicus, “not-friend.” Dual-focus epics are thus populated with characters who, structurally speaking, may be identified as friend and not-friend. The system’s duality is regularly carried in character names, from Hesiod (Law/lessness), Old Testament judges (Gideon’s other name is Jerubbaal, meaning “contend with Baal”), and medieval religious texts (Anti/christ) to comic strip heroes (the Avenger), science-fiction films (Them!), and westerns (out/laws). Indian myth takes the system one step farther. Not only is Ahi the water dragon known as Vṛtra, meaning the evil one or simply the adversary, but Vṛtra is overcome by Indra the fertility god who is also known as Vṛtrahan, the slayer of Vṛtra the opponent. Dual-focus epic always depends on the opposition of a Vṛtra to a Vṛtrahan, an adversary to an adversary killer, a foe to a friend, an other to a self. Dual-focus pastoral follows a similar route, opposing male to fe/male and man to wo/man. The rhyme is built in, because the underlying structure always already depends on the presence of rhyming characters and values.

Replacement Operations and Polarity Adjustment

Concentrating on principles of opposition, I have thus far paid little attention to the development of dual-focus texts over time. In one sense, this is appropriate, because dual-focus narratives work very hard to highlight static oppositions and questions of space. Dual-focus texts are not without plots, but those plots always seem to serve the text’s fundamental duality. Much has been written about the structure of novelistic plots, but most novel-based conclusions simply don’t apply to dual-focus strategies. A new analysis is needed, stressing the specificity of the dual-focus approach.

Our guiding metaphor thus far has been the chess game, with its clear opposition between equivalent but opposite players. We have now reached the limits of this metaphor’s usefulness. The chess analogy exemplifies quite well the text’s synchronic aspect, but it has less to say about the diachronic progression of the text. Another metaphor now suggests itself, one that is central to both classical and Christian dual-focus traditions. Throughout The Iliad and then again at the end of The Aeneid we are told that the king of the gods holds the fate of mortals in his hand as he would hold an equal-arm balance, with the Greeks or Aeneas on one side and the Trojans or Turnus on the other. Christian mythology borrows this motif, transferring it from the battlefield to the soul and calling it psychostasis or the weighing of the soul. With St. Michael holding the scale, good deeds fill one pan and bad acts the other. As in the classical motif, the pan that outweighs the other is the winner. Once weighing has taken place, the soul’s fate is decided and the text is finished.

Dual-focus texts are conceived as a process of weighing. Beforehand, the scale is stable. Afterward, the scale once again achieves stability. Only in between, during the process of weighing, does the scale oscillate. In order to continue, the text must avoid permanent resolution of its seesawing motion. The opening section of this chapter argued that dual-focus texts typically begin by a process of splitting, which organizes an initial chaotic situation into two antithetical principles, groups, or characters. This split presides over the text’s synchronic component, but something else is needed to initiate the dual-focus diachronic dimension. The Old Testament book of Judges offers useful insight into this process. The Pentateuch serves to establish a claim to power and value, with the Israelites separated from those around them, valorized by a special covenant with God, and organized according to laws prescribing the conduct required for extension of that privileged relationship. Joshua, the book directly following the Pentateuch, completes the establishment of the Israelites—with God’s help they reach the Promised Land, where they enjoy a position of power and stability. But in stability there is no text. The book of Judges exists not because everything continues to run along smoothly but because the people of Israel continually “did what was evil in the sight of the Lord” (a formula that is repeated no fewer than eight times: Judges 2:11, 3:7, 3:12, 4:1, 6:1, 8:34, 10:6, 13:1). Whenever the Israelites stray from the source of their strength—the Law and its Giver—they empower their foes and mobilize a new section of the text. To the periods when the people of Israel are obedient and dominate the land from the Jordan to the sea, the text accords not one word, for the continued existence of the text depends on maintaining the suspense—literally and figuratively—during which no one knows which way the scales will tilt. Judges becomes a model for the remainder of the Old Testament, which oscillates between straying from the Law, with a consequent loss of power, and periodic returns to the power engendered by proper belief and action.

Dual-focus rhetoric firmly allies readers with one side, but the diachronic aspect of dual-focus texts requires a rupture between sympathy and power. The plot isn’t set in motion until the fate of the rhetorically privileged side appears to be in doubt. A real-world example may be of some use here. For decades during the twentieth century, world politics depended heavily on the notion of a “balance of power.” As long as a power balance subsists, this dual-focus theory asserted, the gates of war remain closed. But when the Soviets sent Sputnik into orbit, the newspapers were suddenly cluttered with comparative graphs, terms of imbalance like “gap” or “lag,” and new versions of the perennial Ivan-Johnny contrast, all triggered by fear that the imbalance might turn into war—the larger text that balance of power politics attempts to keep from being written. “What made war inevitable,” Thucydides says at the beginning of The Peloponnesian War, “was the growth of Athenian power and the fear which this caused in Sparta” (1954:25). It is here that Thucydides begins his text, and not with a detailed account of the years of peace preceding the war, for the breakdown of the balance of power and the text are simultaneous and in a sense synonymous. In The Song of Roland only a few lines are needed to relate Charlemagne’s successful Spanish campaign. For seven years, the Holy Roman Emperor had achieved a continuous string of victories, yet the poet shows no interest in that portion of history. What attracts the poet—what constitutes a dual-focus plot—is the breakdown of Christian unity, the consequent reduction of Christian strength, and thus the challenge to Christian superiority. Just as each episode in Judges begins when the people of Israel stray from God and his Law, so Roland is set in motion by Ganelon’s straying from his feudal responsibilities.

Ganelon belongs to a class of characters that we may conveniently label as “middlemen.” Refusing to be fully defined by the duality that organizes the text’s synchronic existence, middlemen cross the line that separates the text’s two constitutive groups, thereby disturbing the delicate balance between the two sides. Homer’s Iliad offers a particularly clear example of the functioning of dual-focus middlemen. Ever since Aristotle’s attempts to squeeze The Iliad into the biographical mold that he applied to The Odyssey, Homer’s martial epic has been consistently misread, the Trojan war being treated as a function of Achilles’ anger rather than vice versa. In short (with the exception of a few passages in Whitman 1958 and Sheppard 1969), Iliad criticism has suffered from the same problem that has so long plagued The Aeneid and The Song of Roland: a fundamentally dual-focus text has been read as if it had only a single focus. The Iliad makes much more sense when it is treated as a dual-focus epic triggered by Achilles’ alienation from his group, thus producing an imbalance between Trojans and Greeks. The mechanism by which Achilles becomes a middleman deserves attention, because it demonstrates especially clearly the dual-focus tendency to handle every situation in binary fashion. The middleman is not an independent category lying between Greeks and Trojans but is instead generated out of an internal conflict formally identical to the larger Greek-Trojan battle.

At the outset Chryses brings the wrath of Apollo down on the Greeks for their unwillingness to return his daughter Chryseis, but when she is sent home, their safety seems assured. Agamemnon, however, is far from satisfied; he resents losing Chryseis and thus resolves to replace his lost prize with Achilles’ captive Briseis. This series of replacement operations, substituting one anger for another, forces Achilles into the role of opponent. It is Achilles’ plea to Zeus (through his mother Thetis) and not Chryses’ invocation to Apollo that spells the beginning of the Greeks’ misfortune. Not until Book XVI, where Achilles reverses his original plea to Zeus, will the Greeks’ fortune change, and not until Achilles himself decides to reenter the combat in Book XIX will the Trojans’ fate be sealed. The Iliad is not Achilles’ book but a clever combination of international and intranational strife. It is Achilles’ role at the intersection of the book’s two conflicts (the Greek-Trojan battle and the quarrel with Agamemnon) that forces him into the role of middleman. This composite formula will become the model for many a later dual-focus text, including the Hollywood western and several generations of superhero comic books.

Once the dual-focus text has been set in motion by the creation of an initial imbalance (through defection of a middleman, breakdown of group unity, or divergence from the Law), the text proceeds according to a series of replacement operations. Instead of operating through a clear cause-and-effect pattern, each new confrontation seems to be generated automatically, in response to a clear textual need. When one foe is vanquished, another arises, as if out of thin air, to take his place. No bad guy, no text. In Eugène Sue’s immensely popular 1830s serial novel, Les Mystères de Paris, we run through three more or less independent series of adversaries. As soon as the heroic Rodolphe is freed from the threats posed by Bras-rouge and the Maître d’école, the Martial family jumps in to join La Chouette and her evil designs; no sooner are they out of the way than Polidori and Jacques Ferrand present their ugly faces and even uglier schemes. Where did they come from? Who knows? Who cares? Readers are given no more reason to care about the origin of these foes than about the reasons for the timely appearance of new antagonists for Batman, Superman, James Bond, or Wonder Woman. Throughout the dual-focus tradition, adversaries are generated not through a traditional cause-and-effect process but as a necessary function of the text’s structure.

Just as the technique of replacement operations operates quasi-automatically, so are dual-focus actions generated mechanically out of a small number of well-known principles. Because dual-focus characters are usually defined by relationship to a principle or group, they typically act more as placeholders than as independent beings with lives of their own. The opening scene of John Ford’s Wagonmaster presents the Cleggs brothers robbing a store. As they leave, the clerk grabs a gun and wings the head of the gang. “Uncle Shiloh” instantly turns and says: “You shouldn’t of done that.” As if by rote he then shoots down the clerk. The way Shiloh sees it, he has no choice; an affront requires response. “Well I guess I’m gonna haf t’kill ya now” is the basic motif of this necessary reaction common to all but the most sophisticated dual-focus fiction. Where other modes have psychology and motivation, dual-focus narrative depends on automatic mechanisms like honor codes, talion laws, and allegiance to one’s group (be it national, religious, or sexual). As Northrop Frye puts it apropos of comedy, dual-focus characters remain in “ritual bondage” (1957:168) to a particular idea or category, thus depriving them of the independence enjoyed by characters in other modes.

The same principle applies to the progression of the dual-focus text itself. Systematic deployment of metaphoric modulations moves us from side to side in a manner that depends more on formal parallelism than on character choice. The alternating following-pattern thus seems to arise from the underlying dual-focus structure rather than from plot considerations. Consider Xenophon’s short Alexandrian romance known as An Ephesian Tale, which recounts the love story between Anthia and Habrocomes. When we read lines like “Anthia for her part was no less smitten” (1953:73), we probably don’t think twice about how we have modulated from Habrocomes to Anthia. Upon reflection, however, we recognize two separate acts of communication. On the one hand, the narrator provides information about Anthia (“Anthia . . . was . . . smitten”); on the other hand, he draws on an underlying parallelism to justify the movement from Habrocomes to Anthia (“. . . for her part . . . no less . . .”). Each action calls for a matching action, and thus, automatically, for modulation to the counterpart character. The familiar convention of sleepless nights works in the same fashion. “Habrocomes pulled his hair and ripped his clothes,” we are told. As if by rote, the text then tells us that “Anthia too was in deep distress” (73–74).

Thanks to replacement operations and metaphoric modulation, the dual-focus alternating following-pattern moves us through the text in a way that seems automatic and unchanging. A simple story like An Ephesian Tale progresses through a series of oppositions, first alternating between the young lovers Anthia and Habrocomes, then, once they are separated, between their successive captors. At first, this simplicity appears representative of dual-focus narrative as a whole—we always seem to be alternating between Romans and barbarians, Christians and pagans, friends and foes, men and women. Because each new following-unit apparently involves a 180-degree reversal, we have the sensation of always returning to the exact same location, thus repeating the same opposition. A closer look suggests that more is going on in dual-focus texts. As we move through a series of replacement operations, instead of exactly repeating the same opposition again and again we encounter small but meaningful differences in the parameter of opposition. This “polarity adjustment” offers a minimalist but powerful method of making meaning, characteristic of dual-focus narrative.

In The Song of Roland, the importance of the Christian-pagan opposition is eventually compromised by the introduction of additional dualities: group orientation versus individualism, humility versus pride, strength versus weakness, and so forth. This process is facilitated by the dual-focus tendency to oppose clusters of characteristics rather than single features. With each alternation, with each metaphoric modulation, an opportunity exists to vary the properties contained in any given cluster, thereby nearly imperceptibly adding an important new consideration. From a distance, the text may appear monotonous, endlessly repeating the same opposition, with the same clear rhetorical effect, but upon closer inspection we discover a less obvious program.

D. W. Griffith’s controversial masterpiece, The Birth of a Nation, offers a fascinating example of the opportunities available through polarity adjustment. The first half of Griffith’s film alternates between two parallel families, the Stonemans in the North and the Camerons in the South. Before the outbreak of the Civil War, we witness the friendship of the younger sons—eventually destined to meet in battle—as well as the nascent romance of Elsie Stoneman and Ben Cameron. When war comes, we continue our alternation between Union and Confederate sides. As the film progresses, however, the contrast between North and South progressively diminishes in favor of the qualities shared by these noble foes. Little by little, we shift from opposition between the Stonemans and Camerons to a celebration of their hidden commonality—of their shared patrician whiteness—now opposed to the supposedly barbaric qualities of the “Negro race.” Having grabbed our attention by stressing the pathetic side of internecine strife, Griffith now slides to his real topic, the superiority of one race over the other. What appeared to be the historical tale of North versus South has turned into a biased account of white versus black. Just as photographers must deal with the problem of parallax, and cartographers must adjust for the slight difference between true North and magnetic North, readers of dual-focus narrative must remain ever attentive to a slippage in the polarities around which the text is built.

Through replacement operations, metaphoric modulation, and polarity adjustment, the alternating following-pattern of dual-focus narrative is eventually suspended by reduction of the text’s two constitutive foci to one. In dual-focus epic, this process involves destruction or exile of one group. In dual-focus pastoral, reduction is effected through a merger of the two sides. Many texts combine the two approaches. Most descriptions of narrative endings assume that they relate to the body of the text in a manner that is entirely uncharacteristic of dual-focus narratives. Typically used to describe narrative conclusions are paired terms like cause-effect, question-answer, and problem-solution (e.g., Richardson 1997:92, Miller 1998:46, Carroll 2001:32, Abbott 2002:12). None of these is adequate to describe the way in which dual-focus texts end. Instead, the necessary concepts are reversal and apocalypse. Two early Christian examples will prove especially useful for understanding the role of endings in dual-focus narrative.

One of the most influential early Christian texts was The Martyrdom of Saint Perpetua and Saint Felicitas, which became the literary model for the important genre known as the passio or martyr’s life. In only a few pages, this moving text portrays two separate battles. The dominant battle is the one implied by the title: Perpetua, Felicitas, and their friends are questioned, beaten, and slaughtered by the Romans. The day before she is to die in the arena, however, Perpetua has a dream depicting a second battle. Thrust into the arena alone, she is soon attacked by the Devil disguised as an Egyptian, whom she defeats in single combat. In real life under the Romans, Perpetua dies a horrible death, but in her dream she leaves the arena victorious. In its simplicity, this account of martyrdom eloquently demonstrates the double binarity of dual-focus apocalyptic endings. An apparently primary distinction opposes the Christians to the Romans, but that antagonism is eventually trumped by a more important contrast between dingy reality and glorious dream life. Perpetua’s vision cannot possibly be understood as an effect of a preceding cause. Instead, it must be seen as a reversal of the previously presented circumstances, a radical adjustment of polarities. In Perpetua’s flesh-and-blood martyrdom, the operative distinctions involve physical power; in her dream, the outcome depends on spiritual power.

A similar pattern emerges from the familiar story of Dives and Lazarus (Luke 16:19–31), among Jesus’ parables the most commonly depicted in medieval art. This exemplary tale about a rich man and a poor leper is typically recounted in a double diptych. The first image reveals Dives on the left, seated at his table, enjoying the fruits of this world, while Lazarus crawls into a corner on the right, his sores licked by dogs. This first panel is usually drawn or sculpted quite realistically, by medieval standards. The second image, however, is clearly the product of imagination rather than observation. On the left, the rich man burns in the fires of Hell; on the right, Lazarus reposes happily in the comforting bosom of Abraham. The variations on this theme are manifold—on the façade of the south porch at Moissac, in the capital of Vézelay’s south aisle, in Herrad of Lansberg’s Hortus Deliciarum—but the effect is always the same. This world is revealed as nothing but a degraded realm where people are not situated in their rightful place. The connections between the two diptychs include nothing that we can clearly identify as cause and effect, nor are there any strong temporal markers connecting the two panels. This is not a depiction of before and after but of here and hereafter, of the fallen world and eternal life.

Throughout the history of dual-focus narrative, a similar textual organization has held sway. The first part of the text depicts a world of “reversed circumstances,” as one Horatio Alger character put it. The conclusion rights that wrong by reversing the reversal. In many cases, this configuration clearly represents a reaction to a very real historical situation. Before emancipation, African Americans developed a large variety of narrative songs that offered an otherworldly response to the slavery they were made to endure in this world. These “Negro Sprituals” borrowed Old Testament metaphors and apocalyptic mythology as the basis for stories of heavenly triumph over human misery. When Southern whites were defeated in the Civil War, they too sought the kind of comfort easily provided by the magic of polarity adjustment. No text makes the otherworldly nature of the solution more obvious than Griffith’s Birth of a Nation, where the white-robed riders of the Ku Klux Klan seem to float in out of a vision, expressing Southern aspirations of vengeance.

Defeated by the British, the Irish imagined a new life in the land across the sea, thereby shedding their identity as losers to the British in favor of a new identification with the American revolutionaries who defeated the British. Many times over, Irish songs thus repeat the double diptych of defeat at the hands of the British reversed by a triumphal new life in America. In Dion Boucicault’s celebrated “Oh! Paddy Dear (The Wearing of the Green),” the first verse laments past losses and their effect on daily life in the defeated homeland, while the second imagines a new life for the Irish in a land “where rich and poor stand equal in the light of freedom’s day.” Though America may be a real place, it serves the same function in Irish song as dream does for Perpetua or heavenly vision for Lazarus. Because justice in this world seems faulty, dual-focus texts invent apocalyptic realms of perfect justice. Inverting previous events, apocalypse is formally equivalent to revenge, repeating the same stories with the roles reversed.