The dual-focus system is organized as if by divine fiat. Characters are subordinated to prearranged categories. Textual progression depends on an omniscient and omnipotent narrator. Decided from the outset, the locus of value remains invariable. Dual-focus texts thus adopt the ultrarealist position in the problem of universals. General categories are seen as real, concrete entities, whereas the particular objects, individuals, or statements that embody them are considered mere “accidents.” Single-focus narrative, to which we now turn, offers a radically different approach, tending toward the nominalist solution to the problem of universals. According to this system, categories are nothing but abstractions derived from individual cases, names given to express the similarity of certain, quite concrete, particulars. Single-focus narrative typically transfers freedom and authority from the narrator and the divine to an individual liberated from the tyranny of prearranged categories and thus capable of personally creating value. Where characters once left questions of good and evil to their superiors, now individual decisions, desires, and defeats are the ones that count.

The movement from dual-focus to single-focus narrative is thus that of Prometheus, of Lucifer, of Adam, for it is the very fire of the gods that single-focus protagonists must steal in order to escape from the dual-focus universe, where they were imprisoned within the narrow walls of group orientation, preexistent universals, and narratorial whim. It is precisely this progression that Nathaniel Hawthorne portrays in his 1850 novel, The Scarlet Letter. From the start, it is clear that the prison, “a wooden edifice, the door of which was heavily timbered with oak, and studded with iron spikes,” with “its beetle-browed and gloomy front” (1962:38), serves as a figure for Puritan narrowness of thought, morality, and conduct. The “iron-clamped oaken door” (39) is associated not only with the “force and solidity” (40) of the Puritan character, but also with “the grim rigidity that petrified the bearded physiognomies of these good people” (39):

It was an age when what we call talent had far less consideration than now, but the massive materials which produce stability and dignity of character a great deal more. The people possessed, by hereditary right, the quality of reverence; which, in their descendants, if it survive at all, exists in smaller proportion, and with a vastly diminished force in the selection and estimate of public men. (168)

Hawthorne’s novel begins as it does, with Hester Prynne’s exit from prison, so that she may symbolize the modern world’s liberation from the moral, philosophical, and legal chains of an earlier world and “a people amongst whom religion and law were almost identical” (40).

Perhaps the most striking aspect of Hawthorne’s tale of Puritan Boston is his refusal to bend his narrative technique to Puritan law. The Puritan fathers, like the ultrarealists of medieval theology, saw their laws as concrete, preexisting humanity, and oblivious to accidental variation among individuals. Those who failed to obey the law were treated as freaks of nature—morally reprehensible beings who must be so identified by imprisonment, public exposure, exile, or death. With value in the center, the eccentric individual could lay no claim to public sympathy and but little to the very status of personhood. Yet Hawthorne builds his entire novel around a single unconventional individual, whom he follows nearly exclusively from beginning to end. Though Hawthorne’s narrator enjoys a level of knowledge shared by none of his characters, in one domain the narrator is clearly subordinated to Hester Prynne. Waiting expectantly at the prison door for “our narrative, which is now about to issue from that inauspicious portal” (39), Hawthorne reveals from the start that he is unable to tell his story until an outcast, an adulteress, a common criminal should free herself from the confinement imposed by oak and iron.

Far from considering Hester simply an accidental, and thus unimportant variation from the Puritan universal, Hawthorne builds his entire narrative around an individual case. For Hester is his narrative; without her, the novel cannot exist. Without Achilles, the fight and The Iliad proceed apace. Without Roland, the combat still continues. When Vashti fades from Ahasuerus’s court, Esther is there to take up the slack. But should Hester remain in prison, should she be sentenced to death rather than to wear the symbol of her sin, then Hawthorne’s novel would be stillborn. If the following-pattern of The Scarlet Letter concentrates almost exclusively on Hester Prynne, it is because her eccentricity makes her an appropriate subject for a novel. In a dual-focus text she would be reduced to conformity or expelled. Here, however, Hester’s very individuality identifies her as a worthy subject.

The visual configuration of the opening scene highlights and explains the narrator’s interest in Hester Prynne. When she steps into the open air, “as if by her own free-will” (42), Hester becomes like a magnet, drawing all attention to herself, reorienting a haphazard arrangement of similar people into a centered composition reminiscent of a Renaissance nativity:

But the point which drew all eyes, and, as it were, transfigured the wearer,—so that both men and women, who had been familiarly acquainted with Hester Prynne, were now impressed as if they beheld her for the first time,—was that SCARLET LETTER, so fantastically embroidered and illuminated upon her bosom. It had the effect of a spell, taking her out of the ordinary relations with humanity, and inclosing her in a sphere by herself. (43)

Why do those who knew her see her as if for the first time? Something has occurred that goes deeper than a simple change of costume, yet that change clearly figures the quasi-philosophical gap separating Hester from the crowd. The townspeople dress as realists, conforming to a universal costume that disguises, subsumes, indeed denies all individuality. Hester’s attire, however, “which, indeed, she had wrought for the occasion, in prison, and had modelled much after her own fancy, seemed to express the attitude of her spirit, the desperate recklessness of her mood, by its wild and picturesque peculiarity” (43). The Puritan process is here reversed. Instead of conforming to the prearranged model implicit in Puritan dress, Hester has externalized her innermost feelings in the fantasy of her dress. It is this tendency to begin with the particular rather than the general—to favor accidents over categories—that distinguishes both The Scarlet Letter and the class of texts to which it belongs.

The internalization motif associated with Hester’s punishment underlines this new epistemology. To highlight the importance of personal experience, Hawthorne twice measures the distance between the prison and the pillory. Measured by the ruler, that preexisting unindividualized universal, “It was no great distance from the prison-door to the market-place.” But a shared yardstick is not the only gauge applied. “Measured by the prisoner’s experience, however, it might be reckoned a journey of some length” (43). It is a small point, but one that is not lost in Hawthorne’s persistent concern to subordinate the world to Hester’s experience rather than vice versa. Just as length can no longer be considered in absolute terms, neither can standards of punishment. When the older gossips call for still harsher penalties to be heaped on Hester, the youngest of the group cries out in recognition of the psychological impact of Hester’s sentence. Punishment, she implies, is not an external quantity, measurable by any universally applicable standard. Conversely, no external judgment may any longer be taken as a necessary indication of sin. Once Hester spies her former husband in the crowd, her place on the pillory actually becomes a comfort to her. Public exposure, the very term of her sentence, is thus transmuted into shelter. In the new ethic represented by Hester’s conduct, the only effective punishment takes place in the privacy of face-to-face human relations. Meanwhile, the corollary to this principle is demonstrated by Arthur Dimmesdale, Hester’s partner in crime. His experience demonstrates that joy exists only in the privacy of the individual conscience and cannot be guaranteed by the admiration of the gathered throng.

The Scarlet Letter’s opening scene progressively reveals an implicit limitation that has been self-imposed by the narrator. Just as the story cannot begin until Hester emerges from her prison, so the flow of words and scenes is subordinated to the central character: the spatial metaphor is indeed applicable, with those on the perimeter of the circle relating to each other only through the adulteress placed at the center. From a conversation about Hester we follow the gaze of the gossips to the prison door, from which Hester at last emerges. Once Hester has been described, we move back up that line of vision to observe the gossips’ reaction. Returning to Hester, we follow her to the scaffold, only to be subjected once more to her logic: “Her mind, and especially her memory, was preternaturally active, and kept bringing up other scenes than this roughly hewn street of a little town, on the edge of the Western wilderness” (45). Where Hester’s mind wanders, there we must follow, for the narrator has voluntarily become subservient to the character, masking his gaze behind hers rather than maintaining the typical dual-focus stance of domination and superiority.

Only when Hester returns from her mind’s vision to that of her eyes do we see the activities taking place around her, and then only selectively, for in a sense Hester’s vision not only surveys the scene, it creates the scene, according to the workings of her own mind. Her eyes, it seems, are the pen with which the text is written. Wherever she looks, the object of her vision is described by the narrator, as if he were her amanuensis rather than she his creation. When she looks at the crowd from her privileged position above, Hester selects one person to concentrate on, someone who by generally accepted social standards has a right to be considered part of Hester’s story. In the social world, Hester’s husband is vested with rights over his wife; in Hawthorne’s narrative, however, Roger Chillingworth gains existence only when Hester’s gaze calls him into being. The novel’s technique thus directly contradicts the Puritan moral and legal code, according to which a woman, once married, must remain subservient to her husband no matter what the state of her inner desires. The narrative technique chosen by Hawthorne replicates Hester’s physical and mental adultery, for it accords her the right to choose her own partners.

Breaking out of dual-focus constraints, Hester claims the right to compose her own story, to create her own life, the two now becoming synonymous in a fashion that is totally foreign to dual-focus disdain for the fate of the individual. Even Dimmesdale, Hester’s lover, merits a place in the text only when she chooses. In the opening scene, she refuses to name her fellow sinner; the pastor thus passes out of the tale until such time as Hester once again brings him into it, at the governor’s mansion. Even then, her insistence that he speak on her behalf is necessary to call his words into being. Only later will Hester’s husband or partner be seen separately from her, and then only long enough to elucidate Hester’s situation and the difficult decision she must make.

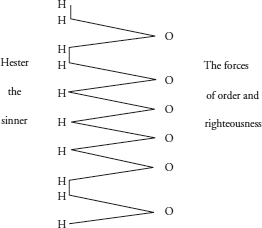

FIGURE 4.1 The Scarlet Letter as experienced through Hester (H, Hester; O, forces of order)

The following-pattern of The Scarlet Letter thus differs radically from what we have seen in dual-focus narrative. Its skeleton is a simple straight line describing the progression of a single central character. Like most single-focus texts, Hawthorne’s novel introduces secondary characters through the protagonist, clearly identifying them as structurally subservient. Movements away from the center are typically produced by some form of metonymic modulation tying the secondary character directly to the protagonist, thereby maintaining the illusion that the protagonist, and not the narrator, is in control of the story. When we leave Roger Chillingworth, after having heard his conversations and watched him observe Hester on the scaffold, we do not move directly to the assembly of magistrates who will speak the words of reproach and ask the questions that could just as well have been put on Chillingworth’s lips, for a metaphoric movement of this type—from the offended one to those who speak for him—would set up a second focus of action, independent of Hester’s power. We would thus return to the domain of dual-focus narrative, with its characteristic opposition between the orderly forces of civilized life and those who would challenge order and civilization.

Hawthorne steers us away from this dual-focus reading by making us pass through Hester each time we move from one aspect of her surroundings to another. From Chillingworth we return to Hester along the path of her gaze, sharing her vision and witnessing the effect on her mind, before moving to the magistrates who are now introduced through their spatial relationship to Hester, rather than through a parallel to the wronged husband whom, in a sense, they represent. Because the narrative material is filtered through Hester, the text is experienced as represented in fig. 4.1.

Were it not for the narrator’s persistent following of Hester, the preponderance of metonymic modulation, and limitation of interior views to the central character, the same material might well have been perceived by the reader as in fig. 4.2. The topic of The Scarlet Letter’s opening scene might reasonably lead us to expect this type of dual-focus presentation. The scene is built around the law and transgression; it apparently opposes the prison to the open space around it; everyone in the scene either defends or decries Hester’s situation. Yet Hawthorne effectively keeps us from configuring this scene in a dual-focus manner. Seen from above, the scene would appear to be adversary in nature as well as presentation, but Hawthorne never lets us view the scene from above. Instead, we are drawn into the scene through Hester’s own experience: we see what she sees. Instead of presenting the clash between the law and an outlaw, the scene is built as a chain of experiences either perceived or induced by the woman who climbs the scaffold. Hawthorne’s technique robs everything in the created world of its independence, attaching all events and characters instead to Hester’s destiny. In a very real sense, The Scarlet Letter has transferred the narrator from a dual-focus position in the divine regions above to a new existence in the human world, for Hester herself has stolen the narrator’s fire. Claiming the right to create a law of her own, a religion suitable for the workings of her own conscience, Hester simultaneously usurps control of the narrative.

FIGURE 4.2 The Scarlet Letter represented as conflict

The interaction between narrator and protagonist in The Scarlet Letter is no mere technical problem. As in dual-focus narrative, the relationship between the novel’s narrator and its characters sums up an entire world-view. Operating like the law and those who enforce it in Hester’s Puritan world, dual-focus narrators know where value is located and thus organize the narrative to highlight the source of value and the consequent duties of the individual. Hawthorne’s narrator pretends neither to such knowledge nor to such control. Releasing characters into a novelistic space that remains to be created, the narrator places a pen at the service of Hester Prynne’s eyes and concerns. Instead of preceding her actions and her thoughts, value must be created by them. Speculation is thus the novel’s—and Hester’s—mode of being: speculation in all its connotations, from the etymological visual sense to the familiar moral, philosophical, and economic meanings. Those around Hester have divided the world in two—the sinless and the sinners—and identified normal life with sinlessness, life within the law. Hawthorne reverses that perspective, defining the human condition as that of the sinner. What makes Hester an appropriate subject for a single-focus novel is precisely her unwillingness to live within the law, coupled with her ability to build a new life around her lawlessness:

Her sin, her ignominy, were the roots which she had struck into the soil. It was as if a new birth, with stronger assimilations than the first, had converted the forest-land, still so uncongenial to every other pilgrim and wanderer, into Hester Prynne’s wild and dreary, but life-long home. (60)

Hester’s life in the new world, like Adam’s, begins with sin, and with the knowledge that it brings of every creature’s fallen condition, for Hester now has “a sympathetic knowledge of the hidden sin in other hearts” (65). She knows that every citizen of Boston shares her sinful condition, yet she alone is empowered to explore the implications of sin. Those around her live in a sham world, protected by the fact that the law holds them sinless. Hester alone accepts her condition and with it the possibility of re-creating the world through the freedom of speculation.

The effect of Hester’s speculation is nowhere more clearly revealed than in the recurrent motif of the maze. In the well-defined topology of dual-focus narrative, labyrinthine structures represent chaos, the diametrical opposite of orderly, civilized space. The implications of this arrangement need hardly be spelled out: the maze must be avoided in favor of the familiar order of civilized life, just as the Puritans evade the labyrinthine ways of moral speculation by respecting their clearly delineated laws. For Hester, no such solution is possible. From the very beginning, her mind harbors two value systems: the one imposed on her from without, the other provided by her human experience. The very fact that, unlike her fellow citizens, she cannot consider the two as coinciding leaves her “in a dismal labyrinth of doubt” (73). Hester’s labyrinth is not external trial but an entanglement of her own making. At any time she is free to return to life within the law, yet she repeatedly rejects this simple exit from her mental maze.

Far from fleeing the maze, Hester continues to choose it. Instead of seeking refuge in the stable values of Puritan life, she accepts the labyrinth as the fundamental condition of human life:

Thus, Hester Prynne, whose heart had lost its regular and healthy throb, wandered without a clew in the dark labyrinth of mind; now turned aside by an insurmountable precipice; now starting back from a deep chasm. There was wild and ghastly scenery all around her, and a home and comfort nowhere. At times a fearful doubt strove to possess her soul. (120)

Like a person wandering about in a real maze, Hester is constantly confronted with two paths, of which she can choose but one. Her conduct can therefore not be produced by simple replication, as dual-focus behavior can be generated. Repeatedly facing a fork in the road, she must instead choose a line of behavior, deriving her action not from a universal but from the very accidents of her particular life. The knowledge that the two paths are not equally good produces doubt; the inability to know for sure which is better produces anxiety. As long as people are “wandering together in this gloomy maze of evil, and stumbling, at every step, over the guilt wherewith we have strewn our path” (126), the cost of sin must be paid in the coin of doubt and anxiety, guilty reminders of the fallen human condition, a heavy price to pay for the privilege of establishing one’s own individuality.

There is, of course, another solution to the problem, which Hawthorne investigated in his next novel, The House of the Seven Gables, but this path Hester steadfastly refuses—that is, to renounce individuality and the claim to private experience in favor of a happy return to the communitarian and predetermined behavior of an earlier Eden, thereby refusing the implications of original sin and individual knowledge. Far from turning back toward an existence that she could not consider as Edenic in spite of the law’s unambiguous assurance, Hester learns from her ordeal to find a home in the very exile that constitutes her punishment:

She had wandered, without rule or guidance, in a moral wilderness; as vast, as intricate and shadowy, as the untamed forest, amid the gloom of which they were now holding a colloquy that was to decide their fate. Her intellect and heart had their home, as it were, in desert places, where she roamed as freely as the wild Indian in his woods. (143)

The decisive meeting between Hester and the minister takes place on the very border of the wilderness because this is where Hester has learned to live. With one foot in civilization and the other in new, uncharted lands, she has constantly felt torn between these two aspects of her personality. Now the time has come for decisions to be made, for Hester to admit that she prefers the wilderness, if only Dimmesdale will escape with her. When he agrees to her proposal, he is immediately identified with the freedom that the wilderness affords: “It was the exhilarating effect—upon a prisoner just escaped from the dungeon of his own heart—of breathing the wild, free atmosphere of an unredeemed, unchristianized, lawless region” (144). Recalling the physical liberation of the opening scene, the forest meeting reveals the human psyche freed from its lifelong submission to a religion of mechanical replication, an ethic devoid of concern for context, and a psychology requiring the sacrifice of individual desire.

The tragedy lies in Dimmesdale’s inability to adapt to this new life. Whereas Hester has had long years to develop her capacity for confronting the unknown, the minister has sacrificed to his social and religious standing any possibility of learning the lessons of liberation. Even the tragedy of the ending, however, only underlines the importance of Hester’s experience all the more. In a world where our sinful condition is taken seriously, where human experience is recognized as the maze that Hester knows it to be, only lonely grappling with doubt and anxiety can eventually teach us how to become comfortable in a new home amidst the labyrinthine ways of the moral wilderness. As R.W.B. Lewis has remarked, “the valid rite of initiation for the individual in the new world is not an initiation into society, but, given the character of society, an initiation away from it” (1978:346).

What Hawthorne so poignantly suggests through the maze motif, he portrays even more clearly through the speculative nature of Hester’s thoughts and decisions, from her original crime of passion to its fully considered reaffirmation in the latter half of the novel. Only when Hester has been firmly established at the center of the narrative does the narrator move away from her long enough to depict the relationship between her husband and her lover. This sequence culminates in Dimmesdale’s nocturnal vigil on the scaffold, where Hester finally discovers the minister’s reduced condition and thus the effect of her decision to respect her husband’s request to hide his real identity. This sequence constitutes the cause for which the following chapter, “Another View of Hester,” presents the effect. This second half of the typical single-focus before-and-after diptych reveals the first signs of change induced by Hester’s forced isolation. Her decision to support the minister in his weakness is presented not just as a change of mind but as a radically new type of decision:

She decided, moreover, that he had a right to her utmost aid. Little accustomed, in her long seclusion from society, to measure her ideas of right and wrong by any standard external to herself, Hester saw—or seemed to see—that there lay a responsibility upon her, in reference to the clergyman, which she owed to no other, nor to the whole world besides. The links that united her to the rest of human kind—links of flower, or silk, or gold, or whatever the material—had all been broken. Here was the iron link of mutual crime, which neither he nor she could break. (1962:115–16)

Here indeed is a new standard of decision-making, and a radically new use for the iron that previously served only to imprison. Having “cast away the fragments of a broken chain” (119), Hester is now free to participate fully in the “electric chain” (111) that she, Dimmesdale, and little Pearl—“the connecting link between those two” (112)—formed as they stood together on the scaffold.

Human beings cannot cast off their bonds entirely. At best they can substitute one chain for another. But they can, if they will, choose their chains, and there lies the telling difference. “Like all other ties,” Hawthorne admits, the new link of mutual crime “brought along with it its obligations” (116); but because the new chain is freely chosen, those obligations are all the more welcome.

Before her vigil with the minister, Hester had committed a crime, as evil a crime as the Puritan code recognizes. Yet in spite of her sin, she nonetheless respects her vows of marital obedience when ordered by her husband to keep the secret of his identity. By the time she finally witnesses the results of this obedience, however, “her life had turned, in a great measure, from passion and feeling, to thought” (119). The significance of her new “sin,” her decision to stand beside her partner in crime rather than her legal husband, thus takes on immeasurably more significance than the original sin. For Dimmesdale, for the continued strength of the chain that binds them, Hester knowingly takes upon her conscience a rejection of all the legal ties that once bound her to Roger Chillngworth: “She marvelled how she could ever have been wrought upon to marry him! She deemed it her crime most to be repented of, that she had ever endured, and reciprocated, the lukewarm grasp of his hand, and had suffered the smile of her lips to mingle and melt into his own” (127). We are most assuredly in the realm of a new law when Hester the adulteress can declare legal marriage to be the greatest crime.

The Triumph of Individual Conscience

It is certainly no accident that Hester should be associated by Hawthorne with the antinomianist Ann Hutchinson or the reformer Martin Luther, for her tendency to predicate value on the decisions of the individual conscience rather than on the community’s religious or legal system clearly reflects Reformation reaction against medieval doctrine and the Roman church:

The world’s law was no law for her mind. It was an age in which the human intellect, newly emancipated, had taken a more active and a wider range than for many centuries before. Men of the sword had overthrown nobles and kings. Men bolder than these had overthrown and rearranged—not actually, but within the sphere of theory, which was their most real abode—the whole system of ancient prejudice, wherewith was linked much of ancient principle. Hester Prynne imbibed this spirit. She assumed a freedom of speculation, then common enough on the other side of the Atlantic, but which our forefathers, had they known of it, would have held to be a deadlier crime than that stigmatized by the scarlet letter. (1962:119)

More than just a reminder of the liberating effect of the Protestant Reformation, or a token of the New England Reformation, which had produced Henry David Thoreau’s Civil Disobedience only a few months before The Scarlet Letter, Hester embodies a parable of reformation, a fable of the changes that take place within human minds, with the capacity to reform the status of every object and action.

Many years earlier (in 1837), in “Endicott and the Red Cross,” Hawthorne had already formulated a primitive version of this tale. Usually cited in connection with The Scarlet Letter because it contains the physical prototype of Hester Prynne, a woman bearing a scarlet letter “thought to mean Admirable, or anything rather than Adulteress” (1962:224), “Endicott” bears still more important structural relationships to the later novel. Having received notice from the governor that the king of England is about to endanger Puritan freedom of worship, Endicott, the commander of a company of Puritan soldiers, the very symbol of order, obedience, and authority, reveals his belief in a principle beyond that of duty to one’s sovereign. “‘The Governor is a wise man—a wise man, and a meek and moderate,’ said Endicott, setting his teeth grimly. ‘Nevertheless, I must do according to my own best judgment’” (225). Ordering his soldiers to form around him like the gossips who surround Hester at the outset of The Scarlet Letter, Endicott speaks a language that Hester will not discover until the second half of the novel: “Wherefore, I say again, have we sought this country of a rugged soil and wintry sky? Was it not for the enjoyment of our civil rights? Was it not for liberty to worship God according to our conscience?” (226). “Who shall enslave us here?” he asks. “What have we to do with this mitred prelate,—with this crowned king? What have we to do with England?” (227). Seconds later, Endicott unsheathes his sword and rends the Red Cross completely out of the banner.

In Hawthorne’s narratorial comment we clearly witness the allegorizing approach that Hester’s speculation suggests:

With a cry of triumph, the people gave their sanction to one of the boldest exploits which our history records. And forever honored be the name of Endicott! We look back through the mist of ages, and recognize in the rending of the Red Cross from New England’s banner the first omen of that deliverance which our fathers consummated after the bones of the stern Puritan had lain more than a century in the dust. (227)

Like Hester Prynne, Endicott is a symbol of the revolution that occurs when people transfer authority from powerful temporal superiors to the small voice of conscience within. “What we did had a consecration of its own” (140), Hester claims to the minister. Conscience, and not the church, is the ultimate measure of consecration. The “electric” chain that holds people together is ultimately stronger than the ironclad oaken door that keeps them apart.

Though Hawthorne does not fully investigate the ramifications of this new system, he does suggest some of its necessary consequences. The much-discussed scarlet letter itself becomes one of his methods for the systematic but oblique revelation of the new role and importance of individual judgment in Hester’s world. Variously described by characters within the novel as representing Adulteress, Able, and Angel, the letter “A” has received still wider interpretation from critics. D. H. Lawrence constructed a veritable lexicon around Hester’s symbol, from Alpha and Abel to Adam, Adama, Adorable, Adulteress, Admirable, America, Mater Adolerata, and beyond (2003:85–86). What does the scarlet letter mean? Different things to different people. The first gossip to comment on Hester’s richly embroidered “A” gives vent to emotions that sound suspiciously like the product of jealousy:

“She hath good skill at her needle, that’s certain,” remarked one of the female spectators; “but did ever a woman, before this brazen hussy, contrive such a way of showing it! Why, gossips, what is it but to laugh in the faces of our godly magistrates, and make a pride out of what they, worthy gentlemen, meant for a punishment?” (1962:43)

The next onlooker is less concerned by Hester’s needlework skills than she is enraged by Hester’s rich gown, when she has naught but rags of rheumatic flannel. Continuing to provide a mirror for the deepest emotions of those around her, Hester’s “A” calls up the hidden sin of the youngest woman in the group, revealing her secret knowledge of the inner price exacted by sin. “Do not let her hear you!!” she whispers. “Not a stitch in that embroidered letter, but she has felt it in her heart” (43). When Hester later appears at the governor’s door, the bond-servant who greets her reveals in like manner his concern for the shine and delicacy of upper-class finery, “perhaps judging from the decision of her air and the glittering symbol in her bosom, that she was a great lady in the land” (76).

The public’s inability to consider the scarlet letter as an objective symbol soon frees Hester’s badge from negative connotations altogether. Eminently practical and fundamentally more concerned with day-to-day necessities than with strict application of the Law, the common people of Boston soon reveal their work ethic by refusing “to interpret the scarlet ‘A’ by its original signification. They said that it meant Able; so strong was Hester Prynne, with a woman’s strength” (117). Proof that Hester has effected some transformation in the mental patterns of her fellow Bostonians is clearly revealed in their new and infinitely more nuanced view of her “A” at the end of the novel: “The scarlet letter ceased to be a stigma which attracted the world’s scorn and bitterness, and became a type of something to be sorrowed over, and looked upon with awe, yet with reverence too” (185). Even little Pearl infuses the embroidered letter with the only value system that she knows. When her mother discards the letter, Pearl is convinced that she herself has been rejected, that she has lost her mother’s love. Only when the letter has been returned to its accustomed place will the child, once again sure of maternal affection, return to her mother’s arms. Thus Hawthorne transfers the locus of meaning from objects to minds, from action to vision. Just as Hester creates a new value system through speculative thinking, so is meaning derived from considerations of point of view—“speculation” in its etymological sense.

In dual-focus narrative, where action is not divorced from meaning, the flow of the story depends largely on a relatively straightforward presentation of actions and words. In The Scarlet Letter, where meaning depends on purpose, thought, and intention, a narrative technique of a different sort is called for. Without internal views of the characters, we have no way of evaluating or understanding them. The old system stressed punishment rather than guilt, result rather than intention. It is significant that Hester is punished not for adultery but for the visible result of adultery. Had she not become pregnant, the punishment would never have been exacted. Yet the reader’s view is not that of the magistrates. The narrator’s attention to the characters’ inner lives provides a necessary component of the new internalized system. To Dimmesdale’s parishioners, he appears the very type of sainthood, a sinless individual entirely devoted to God. The novel affords the reader a view that the public will never have. Not only are we privy to Dimmesdale’s sinful past but also we witness his concern over “the contrast between what I seem and what I am!” (137–38) and thus judge him accordingly. Chilling-worth, too, is evaluated according to this same method. The public sees him as a talented doctor who exhibits devotion to his patient beyond the call of medical duty. Yet we can have little sympathy for him. The old system condemned above all else those acts that threaten the community and its values, but we know that Chillingworth has committed the Unpardonable Sin because we have seen him violate the sanctity of the individual conscience.

In the same way, we learn to have a high opinion of Hester’s virtue because we can see both that her illegal actions are motivated by concern for Dimmesdale’s health and salvation and that her virtuous actions are no longer engendered by the habit of lawfulness but by a deeper, more freely chosen purpose: “With nothing now to lose, in the sight of mankind, and with no hope, and seemingly no wish, of gaining any thing, it could only be a genuine regard for virtue that had brought back the poor wanderer to its paths” (116). Even the very accusation of sinfulness and the right to erase its marks are now removed from the public arena. When Reverend Wilson offers to remove the scarlet letter from Hester’s breast in exchange for the name of her fellow sinner, she shows that she has a far deeper understanding of punishment and repentance than he. “Never!” she cries. “It is too deeply branded. Ye cannot take it off. And would that I might endure his agony, as well as mine!” (53). Renewing this motif, Dimmesdale later rejects the Puritan tenet that the society and its representatives are solely responsible to decide who is guilty and who is not. Taking his accusation into his own hands, he too usurps the role formerly exercised only by God’s own magistrates on earth. If conscience would claim the right to judge the individual’s own guilt, then it must take on as well the responsibility to reveal that guilt.

The Scarlet Letter’s subjective approach to reality, its insistence on the mediatory effect of individual conscience and vision, leads directly to a new relationship between time and values. In dual-focus narrative, the value structure exists outside of time—before time, as it were. From day to day, from year to year, the same actions retain the same value. The victory that takes place at the end of the text, at the end of time, is no more than fulfillment of what has been apparent all along. When the true and princely identity of the lover has finally been discovered, he and his chosen bride are finally freed to exercise fully their functions as male and female; yet they have all along been performing according to the sexual parameters that define them. Nothing new, in terms of value structure, takes place at the end, save that the level of dream is transferred to that of reality. In dual-focus epic, where all the characters similarly incarnate specific values from the start, valuation depends not on their actions but vice versa. The value structure thus remains at all moments the same; its consistent, convenient codification by laws testifies to this fact. From the point of view of values, time doesn’t exist in dual-focus texts. The system remains static. Just as we can choose any action in Puritan society and evaluate it adequately by reference to fixed laws, so we can perform a sampling operation anywhere in the dual-focus text and measure the value of the actions there performed by reference to the code of values glorified by the text.

In The Scarlet Letter no such operation is possible. People change, and since single-focus value depends on individual intention, value structures change as well. For individuals who live within the law, every action is sure, its value uncompromised by considerations of past or future. For Hester Prynne, however, every act becomes an economic speculation, an investment of present capital in a personal view of the future. When Hester agrees to keep the secret of Chillingworth’s true identity, she does so in part out of marital duty but also out of utilitarian motives, based on an assumption that the future will be brighter if she conceals the truth. Soon, however, Hester discovers that her dutiful silence has been poorly invested, for it contributes to Dimmesdale’s demise. Deciding that she must reverse her original decision, she tells the minister that her revelation is provoked by concern for truth (139), but our internal views of Hester have already revealed that she is no longer tied to the old morality and its universal laws of marital fidelity and honesty. This is no simplistic Cornelian opposition of mutually exclusive universals but the occasion for a radical reworking of the concept of honesty. Hester’s decision is based not on invariable law but on the projected effect of individual action. She believes that Dimmesdale’s pain will be relieved by her revelation and that his peace is more important than any other consideration: “Hester saw—or seemed to see—that there lay a responsibility upon her, in reference to the clergyman, which she owed to no other, nor to the whole world besides” (116).

Or seemed to see—there’s the rub. No final evaluation is ever possible in this new world of doubt and anxiety. Hester must always predict the potential future value of every action in this value-market. She must always wager the present on the future. Her experience has taught her that wrong choice is possible, that value is not stable but can be lost—a danger not faced in the Puritan legal system. Yet value can be won as well. If her decision to permit Chillingworth to separate her from Dimmesdale leads to radical desexualization, and loss of the sun’s life-giving power, her change of heart, reestablishing her links with the minister, contributes to a transfiguration of her whole being. Her cap is removed, releasing the femininity of her long hair. The crimson flush returns to her cheek:

Her sex, her youth, and the whole richness of her beauty, came back from what men call the irrevocable past, and clustered themselves, with her maiden hope, and a happiness before unknown, within the magic circle of this hour. And, as if the gloom of the earth and sky had been but the effluence of these two mortal hearts, it vanished with their sorrow. All at once, as with a sudden smile of heaven, forth burst the sunshine, pouring a very flood into the obscure forest, gladdening each green leaf, transmuting the yellow fallen ones to gold, and gleaming adown the gray trunks of the solemn trees. (145)

Human rhythms are no longer subservient to those of nature; nature instead reflects the decisions of each individual. The world becomes a speculum, a mirror in which men and women see the values of their own consciences reflected. Hester’s new decision has not simply restored her to the previous level, it has brought to her a “happiness before unknown,” a surplus of value produced in the market of conscience by her speculation. Yet even this moment is transitory. The parable of the talents makes it abundantly clear that only a constant reinvestment of one’s freedom can produce the desired result. At every moment we must reformulate our being, not in terms of an impersonal, static legal system but in terms of the potential effects of a particular decision on a specific future.

Hester’s daughter Pearl objectifies this speculation. “Of great price,—purchased with all she had,—her mother’s only treasure” (66), Pearl evokes Christ’s teaching on the kingdom of heaven, a value both absent and future, attainable only by abandoning all traditional values. Those who follow the law need not undergo this radical emptying of the self with each transaction. Every decision that Hester makes, on the contrary, is “purchased with all she had.” Because her actions reflect not an impersonal system but her very soul, each action engages the self, risks the self in a wholly new fashion. Sin—as well as righteousness—must now be reinterpreted from the standpoint of its effect on the future. The present thus becomes connected to both past and future in a new way, unknown within the dual-focus realm. Because decisions remain forever subject to change, the effect of one moment on another must be subjected to repeated analysis. Yet there are aspects of the past that we cannot change. Pearl exists, along with the “sin” that gave her life. We are thus condemned to evaluate the present as a function of past and future. Decisions of value no longer exist in a timeless present, oblivious to past sins and future potential.

The seeds of The Scarlet Letter, it would seem, are those of the typically dual-focus eternal triangle: a young and saintly hero contends with an old, jealous, devilish husband for the heart of a desirable maiden. The Man of God versus the Emissary of Satan. But this is neither the substance nor the form of Hawthorne’s novel. The Scarlet Letter turns this typical dual-focus pattern inside-out, revealing just enough of the two men for us to understand the hesitations, the decisions, and the development of the woman. Concentrating on her instead of them, the novel internalizes strife and predicates its action on psychic progress rather than territorial struggle. If Hester is unable to remain mistress of her physical fate until the end—the minister’s confession and death clearly demonstrating the cost of mistaken decisions—she nevertheless shows, in the conclusion, that her long apprenticeship to solitary life and speculation has provided her with the force and independence necessary to maintain her individualism and develop her progressive ideals. What is at stake in The Scarlet Letter is nothing less than the place of the sinner in the literary and social world. Dual-focus narrative simply expels eccentric individuals. Hester’s story offers a new view of both world and text, where every individual is acknowledged as a sinner and thus becomes the protagonist of her own text.