The body of this book has been devoted to two complementary methods of considering narrative texts. The rhetorical approach concentrates on the fluid relationship between reader and text that is created by the following-pattern. Constitutive of narrative itself, the process of following (along with its attendant panoply of modulations) positions the reader in a specific relationship to the characters and their actions. The study of following thus represents a necessary initial step in the understanding of narrative meaning. Limited to the bounds of a single text, the rhetorical approach is usefully complemented by a typological approach, which acknowledges the existence of common organizational and signifying practices—single-focus, dual-focus, and multiple-focus modes—across a large corpus of narrative texts. Recognizing in any given text the play of diverse typological traditions, we are better able to understand not only how individual texts signify but also how entire narrative traditions take on meaning. In this theoretical conclusion, I consider a third way of understanding narrative texts, the transformational approach, and show how it interacts with rhetorical and typological approaches to constitute a fully formed model of narrative reading.

The process of reading may be conveniently broken down into two separate operations. For every reader, the experience of a text includes a chronological unfolding, word after word, image after image, scene after scene. This prospective view of the text is largely guided by the narrator’s decisions. We circulate among characters and places, not according to our own interests but according to an itinerary fixed by the narrator. The process of following determines our progress through the text, in the process dividing the narrative into constitutive segments. We read a novel word by word and sentence by sentence. We watch a film frame by frame and shot by shot. Each form has its own particular base language that we must experience prospectively, piece by piece.

What permits treatment of diverse forms according to the same fundamental method is their shared narrativity, stemming from a common tendency to complement their base language with divisions defined by following (a process which, as outlined in chapter 1, assumes the constitution of “characters,” as well as a particular relationship between a “narrator” and those characters). To understand narrative, we must reserve an important place for the Pied-Piper-like action of following, with its characteristic division of the text into following-units, connected in turn by modulations. In this system, modulations play an important role, for they serve to mark the arrival of a new unit, thereby reinforcing the successive unfolding of the text. The articulative function of modulations also serves to define the pairs of units that characterize our prospective experience of the text. Each following-unit, as it appears, is tied to the previous one, reinforcing a chainlike perception of the text, where each link gains its meaning from attachment to its neighbors.

If it is inaugurated by the process of “following,” the act of reading also involves a tendency toward “mapping.” The process of following keeps our attention constantly riveted on current experiences—with a thought toward those to come—but the techniques that contribute to the constitution of a narrative map all require a large measure of retrospection. Calling on our memory of the text at hand, as well as our prior experience of other texts, the process of mapping involves the reader in a perpetual return to the past, and a constant attempt to define the present in terms of that past, permitting eventual understanding of the present. Whereas the rhetorical dimension of narrative texts depends heavily on the narrator/character relationship, narrative mapping is primarily dependent on character/action considerations. It is to this aspect of the narrative text that we now turn.

How do we make meaning? Through what channels does the process of understanding flow? Which analytical techniques best utilize the mind’s methods of apprehending reality? In describing the act of reading, it is appropriate, I suggest, to recognize two different types of mental activity. The component of reading that I have labeled “following” is heavily marked by the linguistic nature of the text. We read words and sentences one after the other, making sense of them according to the rules of a language that we already know. We need no special terminology to describe this aspect of reading, for the text itself constantly provides all the terms necessary. In the Grail romances we read lines like “The story now leaves them and returns to the Good Knight.” What resources do we need to understand this statement? Only those of language itself. We need to know about antecedents and pronouns in order to understand the term “them,” about epithets and attributes to identify the “Good Knight” as Galahad. Our analytical terminology for dealing with this phase of reading can be borrowed, by and large, from the vocabulary developed for describing the text’s base language—whether English or Old French, moving or still images, paint or celluloid.

The process of mapping, however, involves other concerns entirely. In terms of language, as well as following, there is little difference between Henry’s entry into battle at the end of The Red Badge of Courage and John Wayne’s archetypal role in one western after another. When we map these skirmishes, however, they produce radically different meanings. For young Henry to gather up his courage and enter the battle like a man, he must overcome his earlier fears, master himself, and exit permanently from childhood. Our opinion of his action at the end of the book is radically marked by what we have seen of him along the way. In retrospect, we might say that Crane’s treatment of Henry’s entry into battle is not a description of battle at all but a displaced evocation of maturation, a verbal portrait of the process of becoming a man. In terms of language and following, then, there is a battle, but in terms of mapping there is a reversal of Henry’s earlier failure and thus a sketch of growth, not of death. When John Wayne faces the Indians, however, an entirely different map is drawn. Mirrored in Wayne’s patience and resolve is the irresponsibility of Wayne’s renegade foe, his skittish ponies, his gun-running suppliers, his bloodthirsty supporters. Unlike Henry, Wayne never had to become a man. He was born that way: strong, impassive, courageous. Although the language may from time to time resemble that used for Henry or Galahad, the viewer maps not progression but an eternal opposition of civilization to barbarism, the same clash that once opposed David to Goliath and Aeneas to Turnus.

The process of mapping requires us to read one activity in terms of another, one character in terms of a counterpart. Following depends largely on linguistic meaning to develop its meaning; mapping, by contrast, involves a network of comparisons between diverse parts of the text, for only through sensitivity to the text’s implied interconnections are we able to recognize situations where different textual meanings arise out of similar linguistic situations and so fully realize mapping’s capacity for recognizing and respecting difference. It remains unclear, however, exactly how the process of mapping actually takes place, according to what principles different parts of the same text are drawn together to constitute a textual map.

Narrative makes sense largely in terms of characters and their actions. Lyric poetry may make meaning through verbal textures, evoking a state of being, an atmosphere, or a particular sensibility, but texts are understood as narrative only through systematic reference to their character/action complex. This tendency to make meaning in a particular way is exactly what we acknowledge in recognizing a text as narrative. As we devise a critical language appropriate to narrative mapping, two basic principles must then be taken into account:

As we read, absorbing the author’s words one after the other, we begin to map the text. But since the process of mapping is by nature relational, dependent on connections between one part of the text and another, it is by definition destructive of the text’s purely linguistic existence. As Emma Bovary contemplates the shining city of Rouen from her coach toward the end of Madame Bovary, we marvel at the poetry of Flaubert’s description, his ability to evoke Emma’s desires. In narrative terms, however, we dismantle this discourse, seeing in it a Romantic pendant to Charles’s mean view of the same scene when he was a student, as well as Emma’s unconscious transposition of her own dreams (whose language we find here repeated and trans-formed). The specificity of Flaubert’s language dwindles as we turn verbal patterns into narrative patterns. When we consider Emma’s picture of Rouen in terms of Charles’s view, it is the Romantic nature of Emma’s character that stands out, but when we compare Emma’s image of Rouen to her earlier dream visions, it is her diminishing hold on reality that comes to the fore.

Far from damaging Flaubert’s text, this process of reduction constitutes a necessary and appropriate response to the nature of narrative. In order to map the narrative, we must be able to relate one part of the text to another; in order to relate one part of the text to another, we must be able to express both parts in terms of a common language. This common language, created by and for the mapping process, may seem to bowdlerize the verbal text (indeed, it does so to the extent that the creation of narrative meaning necessarily builds on and thus represses verbal meaning), but it is essential for the apprehension of the text’s narrative structure. As key relationships are discovered in the text, a new language is formulated to serve as a common denominator of the related segments. Since a text’s narrative meaning is always expressed as a series of relationships, and since these relationships must be discovered and expressed by the observer (sometimes with the help of a narrator eager to impose certain types of relationship), the mapping process necessarily involves constant repetition of the relation/reduction sequence.

This new mapping language, necessarily reductive in nature (because it can’t make meaning without reducing differing linguistic phenomena to their underlying similarities), is always expressed in terms of what linguists call “cover terms,” expressions whose generality permits them to refer simultaneously to two or more different phenomena. Because of their ability to identify aspects common to apparently dissimilar objects or events, cover terms have the power to reveal similarity where only difference was previously visible. With cover terms, relational and reductive qualities are inseparably linked. Critics use cover terms not simply as a matter of convenience but in recognition of the way narrative meaning is made. We note relationships between passages, then devise terminology to express the shared qualities that led us to note those relationships. The terms created via this process constitute our mapping language.

The mapping language appropriate to a text’s narrative aspect always engages cover terms of a similar nature. Because narrative depends, by definition, on the character/action complex, narrative cover terms may conveniently take the form of subject/predicate summary sentences. The decision to map the narrative component of a text carries numerous limitations, however, for the very notion of narrative brings with it a heavy load of cultural baggage, including a set of implicit guidelines for the elaboration of narrative maps. The need to concentrate on character/action relationships constitutes the first such narrative servitude. The second involves the identity of the subject in the typical subject/predicate cover sentence. When, in the wake of Vladimir Propp, 1960s French structuralists set about dividing stories into their component parts, with each unit summarized by a short sentence, they quickly discovered that the same action can be summarized in several ways and that a passive summary sentence creates a totally different emphasis from an active sentence summarizing the same action. To bypass this potential reversibility of subject and predicate, the French structuralists decided to concentrate on the “agent” of each action, reasoning that the active elements of a tale are the ones that advance its action. While the tautological nature of this claim makes it, in a sense, irreproachable, such logic nevertheless begs the question of the importance of “action” to narrative structure.

Inaction is hardly an unknown narrative topic. Take, for example, Balzac’s novelette Le Curé de Tours. Reflecting the earlier titles considered by Balzac (“La Vieille fille,” “L’Abbé Troubert”), the plot involves the machinations of Sophie Gamard and her politically influential boarder, the priest Troubert, to evict and discredit another boarder, the inept abbot Birotteau. Strategically, the role of old lady Gamard is of capital importance, for she is the intermediary through whom all the book’s actions must pass. The prime mover, however, is clearly Troubert, for it is his secret political influence in both Tours and Paris that causes the fight between the old maid and Birotteau and, ultimately, the latter’s expulsion from Tours. Domestic strife or political intrigue—which is it? Neither, for rather than concentrating on either of these possible plots, Balzac focuses on the least active and intelligent of his characters. We never observe Gamard in the act of playing her dirty tricks on Birotteau; instead, we see the poor priest reacting to the old lady’s machinations. We always learn about Troubert’s influence indirectly, never by following him independently. We follow Birotteau systematically from beginning to end, always concentrating on his limited view, even when trickery and influence are located elsewhere.

When we begin to map Le Curé de Tours, we repeatedly connect passages concerning changes in the career or comfort of l’abbé Birotteau. The others may be the agents, but he is the one around whom the story is built. Clearly identifying Birotteau as central, the following-pattern sets rhetorical priorities for reader and critic alike. If we map Balzac’s novelette in terms of the weakest character, if we chart The Song of Roland in terms of both Saracens and Christians, if we map War and Peace in terms of numerous characters, it is because the following-pattern remains our primary indicator of narrative rhetoric, our principal method of sensing emphasis. Construction of a plot around a particular following-pattern predisposes readers to notice relationships of a specific type and to draw a particular kind of narrative map.

The retrospective process of mapping takes place at an undefined rate of speed and to an unspecified degree, depending on the text, the reader, and their cultural contexts. Popular fiction is either rapidly mapped, according to widely familiar principles, or not mapped at all (an option open to all readers, but especially characteristic of suspense-novel readers, who typically prefer the prospective aspects of the reading process). The “classics,” on the other hand, never cease being mapped. Complex and multifaceted, these familiar texts are the ones that we are likely to reread throughout our lives, each time contributing anew to a partially drawn map of the text (or, in exceptional circumstances, beginning a new map according to revised principles). Some readers map consciously and conscientiously throughout their lives. Some never map. Most vary their mapping level according to cultural and personal norms, mapping Dante more than Saint Francis, Flaubert more than Dickens, film more than television, and “serious” programs more than variety shows. Whether our mapping activity is substantial or minimal, however, whether it is conscious or not, it remains governed by certain recognizable principles.

The narrative mapping process is characterized by recognition of relationships connecting specific character/action units of the text. Leading to more or less explicit reduction of the text to cover-term summary sentences expressing the noted relationships, this recognition constitutes the surveying activity on which narrative mapping depends—always a relationship, never a single isolated term. Though the textual passages whose relationship we perceive are extremely diverse, the connections that we establish correspond to a very small number of types. The formulaic language of a dual-focus text like The Song of Roland rapidly draws our attention to the transformational relationships connecting and separating Christians and pagans. From the paired councils that open the poem, through the paired attacks that fill up its middle sections, to the concluding paired trials of Ganelon and Bramimonde (the text’s two turncoats), Roland juxtaposes every Christian action with a pagan version of the same action. The significant relationships noted in the process of mapping The Song of Roland thus regularly take the form of

or

Reductive and hollow, these cover terms nevertheless have the virtue of expressing our reasons for sensing a relationship between parts of the text. Whether we note the similar activities of entire groups or the parallel preoccupations of individuals, we find ourselves drawing together, in the mapping process, dissimilar subjects associated with similar predicates. The fundamental form of dual-focus relationships (i.e., those that lead us to experience a text as dual-focus) may thus be expressed in the following manner:

or, to simplify,

or, even more simply,

We recognize this pattern in the familiar paired council scenes of dual-focus epic or the traditional sleepless nights of dual-focus pastoral.

But what about the case of the Charlemagne-Baligant battle, where the distant view of two foes engaged in similar activity is belied by close-ups revealing differences in their motivation and technique? If we sense the Charlemagne/Baligant relationship as especially strong, vital to the process of mapping The Song of Roland, it is not just because the two engage in hand-to-hand combat but also because of numerous other factors: the two hold equivalent positions in their own realms, they are shown preparing for battle in a similar manner, and they fight with equal courage and determination. In other words, an entire context of parallel formal concerns (sequence of scenes, choice of details, reiterated formulaic language) joins the similarity of the combatants’ actual activities in leading readers to sense the transformational relationship that simultaneously unites and separates the two leaders. By the time Charlemagne and Baligant are differentiated according to the sources of their motivation, therefore, the reader has already long perceived the basic configuration:

The problem occurs when we attempt to configure the motivational distinction that eventually leads to the victory of the Christian king—Charlemagne putting his faith in God while Baligant seeks to augment his personal possessions. This is where the deceptively grammatical nature of cover-term summary sentences betrays us. At first, it would seem that the all-important difference in motivation belongs to the predicate, for each thinks and acts in a different way (“thinks” and “acts” = verbs, i.e., parts of the predicate). This is not, however, the way dual-focus narrative operates. Ever renewing the life of that familiar Latin construction, the apposition to the subject, whether with a noun (“Caesar, valiant leader of his legions”) or a verb (“Caesar, having fought valiantly”), with both functioning as adjectives, the attributes of dual-focus heroes are meant to be seen as essential qualities of the confronted subjects.

Recognizing parallelism between dual-focus characters or groups, we implicitly reduce the text’s complex and varied activities to more easily handled subject/predicate cover terms. In this process, predicates at the text’s linguistic level are often transformed, at the mapping level, into adjectives attached to subjects. The differences thus highlighted expand and demonstrate the basic categories subtending the dual-focus world. Part and parcel of the twin processes of replacement operations and polarity adjustment, the attribution of linguistic predicates to mapping-level subjects assures the increasing specificity of the text’s basic terms. From Charlemagne the Christian and Baligant the pagan, we eventually shift to an opposition between feudal fealty and self-centeredness.

The linguistic text passes through a series of transformations: individual words produce relationships, in turn mentally summarized by appropriate cover terms, which evolve as we read (or reread), only in order to be redistributed into the characteristic dual-focus form that allots to the subject all fully representative attributes. The overall process, then, looks something like this:

In this way, the essential concerns of the dual-focus type become embedded in the transformational system that is characteristic of dual-focus narrative.

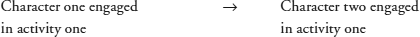

In mapping single-focus narrative, we pass through a similar set of activities, but this time we isolate narrative transformations of a different order, brought to our attention by the practice of following a single character throughout. At the beginning of The Scarlet Letter, we find Hester Prynne hemmed in by the heavy apparatus of Puritan justice. Weighted down by her sin, perpetually surrounded by the village gossips, Hester appears just as shackled in thought as she is bound in body. As the narrative progresses, however, we note sign after sign of Hester’s liberation. She embroiders her scarlet “A,” she comes to savor her sin as expressing a new and bolder morality, she lets down her hair and permits herself to speculate. The characteristic transformational relationship of The Scarlet Letter, and of single-focus narrative as a whole, may thus be expressed by cover terms of this type:

With numerous separate concerns rolled into one, this pair of sentences represents exactly the type of experience that single-focus mapping regularly inspires. Different categories are mixed together, multiple insights are indiscriminately combined, questions of subject and predicate or transformational type are nowhere to be found. For the after-the-fact analyst, however, the system operative here is quite clear. Expressing the changes that she is slowly undergoing, a series of related predicates is associated with Hester. Hester’s stable presence provides an appropriate neutral background against which certain characteristic relationships stand out. Whereas the mapping of dual-focus texts brings us back consistently to a series of subject substitutions, with the predicate being held stable, single-focus narrative reverses the pattern:

The second predicate (“lets down her hair and dares to exercise a new freedom of thought”) must be sensed as a specific transformation of the first (“limits her freedom of mind and body”) in order for the mapping process to be engaged.

It is this recognition of transformation that leads us to segment the otherwise uniform and continuous single-focus text. A silent home movie of a handsome man walking down a road would probably never induce us to begin the narrative mapping process. But if the same man were to walk past an ugly beggar and give him nothing, then open his purse to a second beggar—this one handsome—not only would the narrative mapping process be very likely engaged, but the text would appear segmented into two episodes as well. Mapping and segmentation are engendered simultaneously, triggered by recognition of a transformational relationship between the first and second beggar episodes. It is not possible to establish a neat two-step process in which the critic first segments the text, then notes relationships between segments, for no meaningful narrative segments can possibly preexist the recognition of transformational relationships. Scenes, shots, or chapters may provide a preliminary segmentation, but this division based on textual presentation does not necessarily participate in the production of narrative meaning.

Like their dual-focus counterparts, single-focus texts present numerous specific difficulties in the recognition of transformation and the constitution of summary cover sentences. What, for example, do we do with the adjectival phrases expressing the striking phenomenological transfiguration of Hester’s surroundings, taking her from the moral and physical hardness of the Puritan universe to the soft contours and flowing forms of the forest? And what of our changing access to the narrative voice? At the beginning so often seen from the outside, Hester increasingly takes over the narrative function, gaining through speculation the right to express her own thoughts and desires. We cannot claim that questions of figurative language, atmosphere, or narrative voice obviously “belong” to either the subject or the predicate. Again we find ourselves involuntarily guided, in the practice of transformational mapping, by typological concerns. Immediately recognizing The Scarlet Letter as a single-focus text, we tend very quickly to begin shunting all significant transformations toward the predicate. The relationships between the hard and the soft, the cultural and the natural, the oppressive and the liberating, are understood not as dual-focus oppositions but as a series of developments from one term to the other, seen through the drama of Hester Prynne. There may be times in reading Hawthorne’s novel when we would happily chart the one against the other, sensing as we do the strong differences separating Puritan law from Hester’s growing independence, but as the novel wears on we increasingly put aside the seemingly constitutive dualities in favor of Hester’s changes, which ultimately constitute our high road through the novel. We quickly assimilate nearly all transformations—figurative language, atmospheric considerations, narrative voice, and many others as well—to the evolving predicates for which Hester provides a stable subject.

One might reasonably object that stressing predicate transformation in The Scarlet Letter, or any other single-focus text for that matter, misses the point. The character named Hester Prynne is precisely what does change in Hawthorne’s novel, while the society around her retains its sterile stability. Such a claim would rest, however, on a misunderstanding of the transformational system I am presenting here. That Hester’s development is summarized by a series of cover sentences all having the same subject in no way implies a lack of change on her part. On the contrary, it is the possibility of associating Hester’s name as subject with this particular range and order of predicates that best expresses her specific mobility, her personal itinerary. Just as dual-focus narrative draws us into the mapping process by associating radically different subjects with the same predicate (but only in order eventually to reveal the identity of the predicates that cannot be shared by these two subjects), so single-focus narrative associates a single character with a series of activities, as a method of revealing the important modifications in that character (expressed by the impossibility of transferring certain predicates from one point in her career to another). What we are reflecting, then, when our mapping activity leads us to chart a series of predicate transformations, is not stability of character but the constant presence of that same character at the center of the following-pattern. Whereas dual-focus texts are segmented largely by modulation from focus to focus, the single-focus text is segmented by the protagonist’s constant changes.

If subject substitution and predicate transformation constitute, respectively, the characteristic microrelationships of the macrotypes called dual-focus and single-focus narrative, what remains for multiple-focus narrative? The example of Bruegel’s Elck may be instructive here. All eight characters depicted in the 1558 drawing are involved in diverse bizarre activities. Some are walking around, apparently searching for something with the help of a lantern; others are rummaging through a mound of baskets and bags; still others are engaged in a tug of war. An additional character appears in a poster, gazing at himself in a mirror and accompanied by the caption “Nobody knows himself.” The engraving made from this drawing includes a poem in three languages telling us that “Every man seeks himself,” but “Nobody knows himself.” The engraving also adds the name “Elck” (“Everyman”) to the hem of each character’s garment or the ground beneath. The process of hem-naming, along with the engraving’s interpretive poem, clearly identifies all of the drawing’s characters as versions of the same Everyman, engaged in precisely the same activity. In other words, the drawing is built around a following-pattern that takes us from character to character and from activity to activity, a process typified by the following kind of modulation:

This sequence is reasonably summarized as:

The engraving, on the other hand, facilitates the interpretive process, mapping the multiple-focus following-pattern in terms of a single shared activity engaged in by a series of cloned characters. The diversity of the drawing (corresponding to the process of multiple-focus following) is thus transformed into the homogeneity of the engraving (corresponding to the multiple-focus mapping process). The resultant experience looks like this

This sequence must be summarized as follows:

The characteristic multiple-focus transformation thus turns out not to be a transformation at all but, rather, a repeated movement from one identical unit to another. Whether it is Zola producing multiple vignettes of peasant activity, Griffith interweaving diverse examples of intolerance, or Malraux rehearsing our multiple attempts to escape the human condition, the multiple-focus mode constantly calls on readers to reduce different characters and activities to the same hem-name, the same subject/predicate cover term.

Based on a process that I have elsewhere called “intratextual rewriting” (Altman 1981a), narrative mapping thus proves surprisingly economical, dependent on modest means that can be adequately expressed without complex terminology. Corresponding to the three narrative types developed throughout this book, the basic narrative transformations identified through mapping depend on strikingly simple and easily recognizable relationships.

The well-known Chinese proverb according to which a picture is worth a thousand words has a corollary: in order to understand literary narrative, look at pictorial narrative. The problems of the graphic world may not be identical to the problems of linguistic expression, but the insights gained from close inspection of pictorial texts often outweigh the potential dangers of comparing disparate phenomena. In 1962, the eminent medieval art historian Otto Pächt published a little book entitled The Rise of Pictorial Narrative in Twelfth-Century En gland. Concentrating on marginal manuscript illustrations, Pächt analyzes the process whereby individual, isolated images become organized into recognizable narratives with the images alone carrying a major part of the narrative weight. Instead of illustrating unrelated points in the text, Pächt’s images are presented in pairs, as in figure 8.1. To understand this pair of images, we must recognize the second figure not just as a different drawing from the first, but as representing the same character in an altered position.

The hurried reader may well conclude that such belabored analyses constitute much ado about nothing. It does not take too much intelligence (and certainly no knowledge of narrative theory whatsoever) to recognize that if the first drawing is a picture of Saint Cuthbert being solicited for help, then the second represents the same saint putting out a fire. Our knowledge often gets in our way, however. The fact that we know does not tell us how we learned. Pächt’s Cuthbert images exemplify an important revival of narrative composition in Western Europe, a revival that required readers to learn to recognize and interpret narrative images. What is it that they had to learn, but that we already know? What operations do we unconsciously effect without recognizing that we are doing so? As Pächt explains, the process of reviving pictorial narrative (a classical tradition suppressed by the so-called Dark Ages) involved the creation of paired images representing the same individual engaged in different activities. To this we may reasonably add the creation of a body of “readers” capable of recognizing the two images as representing the same character. For if the viewer assumes that the two figures represent different characters, Pächt’s narrative effect is lost (or, rather, never created).

FIGURE 8.1 Marginal illustration from a twelfth-century manuscript of Bede’s Life of Saint Cuthbert (Courtesy of Bodleian Library, University College, Oxford University)

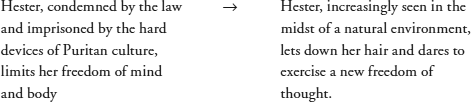

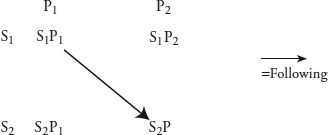

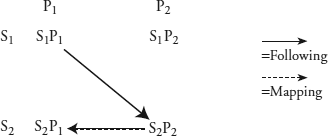

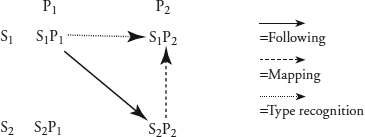

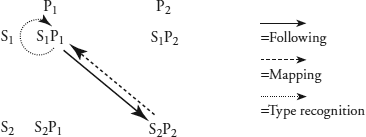

We might summarize this insight schematically in the following manner. While we recognize the Cuthbert pair as the very type of single-focus diptych analyzed above (Cuthbert is asked for help, then Cuthbert provides help, i.e., S1P1 → S1P2), we now understand that an intermediary step precedes our perception of the diptych’s predicate transformation. On first viewing we see two wholly different images, a frontal picture of a figure standing over a kneeling woman (S1P1) and then a representation of a profile figure with his hands raised toward a burning building (S2P2). This difference is soon reduced as we perceive similarities between the two characters (they are of the same height, wear similar clothes, and have similar facial features). Two images that once seemed entirely different now appear related by their common subject. In other words, before recognizing that the two drawings are related by predicate transformation, we must pass through a stage during which the single-focus nature of the narrative has not yet become apparent. The duration of this stage varies according to our familiarity with the written text that the illustrations accompany, our knowledge of period conventions, our visual acuity, and our level of interest. Even later, when we understand perfectly well the artist’s diptych technique, we are still regularly called on (i.e., with each recognition of predicate transformation) to erase substantial differences between drawings, in order to recognize them as representing the same character engaged in different actions.

Precisely the same situation occurs in literary narrative. We must constantly take phrases that are linguistically different and recognize in them references to the same character. We do this automatically, without ever thinking about it (except at those awkward—and telling—points when character identification is not obvious). As Borges’s delightfully iconoclastic character Funes the Memorius puts it, we are entirely accustomed to give the same name to “the dog at three fourteen (seen from the side)” and “the dog at three fifteen (seen from the front).” This process of reducing differences is hardly a natural one. On the contrary, it is a learned ability without which the perception of narrative as narrative would not be possible. For the cultural phenomenon that we call “narrative” has two separate but related conditions of existence. The text must produce multiple renderings of the same character (i.e., differing signs signifying the same character), and the audience must be able to recognize that different signs refer to the same character. The very existence of narrative depends on this cooperation between product and consumer in order to ensure the existence of constructs called “characters.”

Though what reappears in twelfth-century illumination is not really narrative as such, but single-focus narrative, Pächt is surely right to recognize an utterly basic narrative impulse in the simple process of interpreting his Cuthbert diptychs. To recognize a character as a character requires a certain amount of narrative sophistication. Namely, it requires that we be able to pass from the original following-oriented perception, in which differences prevail (S1P1 → S2P2) to a preliminary mapping-oriented perception, where certain similarities surface (S1P1 → S1P2). However rapidly we may eventually reach the highly structured mapping level, we always pass through a preliminary following level, more fragmented and phenomenological.

Dual-focus narrative depends on a similar preliminary reduction, but in this case it operates on the predicate rather than on the subject. The parallel Christian and Saracen council scenes at the outset of The Song of Roland at first hide their connections, with Charlemagne and Marsile each handling debate in his own manner. It is only in retrospect that these initial scenes fully reveal their striking similarity (right down to the details analyzed in chapter 2). Later scenes or actions may immediately appear related (especially once the dual-focus nature of the text has become apparent), but we continue to alternate between perceiving the very real differences separating the activities of the text’s two groups (S1P1 → S2P2) and recognizing the subject substitution on which the text’s dual-focus effect depends (S1P1 → S2P1). The same remains true of every dual-focus text, however conventional or simplistic. The more complex and sophisticated the text, the longer it takes most readers to reduce the difference of the initial reading activity to the transformational relationship of the mapping process.

Where once it seemed that only multiple-focus transformations (S1P1 → S1P1) differed from their related following-pattern (S1P1 → S2P2), we now find a more homogeneous situation. All three types regularly present the reader with new characters in new situations. Though we eventually configure it in terms of the opposition between Christians and pagans, The Song of Roland begins by following, in turn, Charlemagne, Marsile, Blancandrin, and Ganelon, before settling into a clear dual-focus pattern. Hester Prynne shares the opening scene of The Scarlet Letter with the many onlookers who comment on her situation, just as Pride and Prejudice and Le Père Goriot set a large stage with many characters before giving the text over to the single-focus tales of Elizabeth Bennet and Eugène de Rastignac. At the start, these texts share important characteristics with multiple-focus narrative. Only through the mapping process do we ultimately discover the relationships that allow us to identify individual texts with one narrative type or another. All texts initially assault the reader with new material (S1P1 → S2P2). To interpret that material narratively involves reducing utter difference to partial identity. New characters and actions must be recognized as in some sense transformations of characters and actions presented earlier.

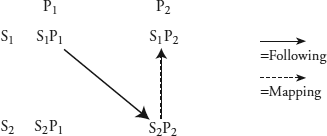

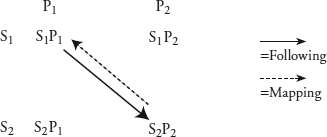

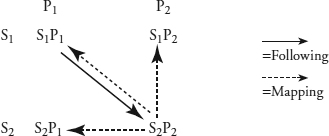

A schematic view of this reading activity may be helpful. All narrative texts progress by the introduction of new character/action units, as in figure 8.2. As we read a dual-focus text, however, we rapidly recognize the transformational relationship linking succeeding units. This recognition “tames” the text for us, bringing the radical newness of the new unit into focus (pun intended), as represented in figure 8.3. Single-focus narrative operates in the same manner, but according to a different transformational relationship, as we see in figure 8.4. The multiple-focus approach involves an even more radical reduction, with new material revealing not just a transformational relationship, but actual identity with the original unit. This pattern may be represented as in figure 8.5. The reading process always begins with progression along the diagonal from upper left to lower right. In order to digest our reading material, however, we must break it into familiar units, suitable to feed our hunger for the known. This need is satisfied by our ability to turn each new unit into a transformed version of a previously encountered unit.

FIGURE 8.2 Introduction of new character/action units.

FIGURE 8.3 Dual-focus reading.

FIGURE 8.4 Single-focus reading.

FIGURE 8.5 Multiple-focus reading.

FIGURE 8.6 Master transformational matrix.

We may thus construct the master matrix represented in figure 8.6, which represents in a single diagram the various versions of the transformational process. For the sake of convenience, I have reproduced this matrix in its simplified 2× 2 form, but texts are of course neither limited to, nor defined by, a single pair of units. The full form of the matrix would extend down and to the right, reproducing many times the relationships visible in the reduced version above (and in most cases combining different types of relationship). This transformational matrix helps us to see that the process of mapping is nothing more nor less than recognizing in unfamiliar material a transformed version of familiar situations.

The term “familiar,” however, suggests a potential shortcoming of this analysis. Thus far, I have attended only to individual texts, stressing transformations of earlier passages in the same text. This is not the only way we make meaning, however. If some readers insist on making a new map for every text, depending heavily on the recognition of internal transformations, others borrow fully formed maps provided by preexisting type concepts. Just what is the relationship between transformational and typological approaches to narrative?

Understanding always involves a dialectic between two activities. Whether we are listening to a new language, reading a novel, or simply visiting a historic monument, we make meaning by noting relationships between the internal parts of the “text.” But in order to recognize a relationship, we must have a notion of what constitutes a relationship: we thus implicitly refer to a master list of types—derived from our experience of other texts—that is potentially appropriate to the text in question. The very fact that we have such a list in the back of our mind has a clear effect on the type of relationships we notice. Once we begin to identify a text with a particular type, we are more likely to notice the corresponding kinds of relationship within the text. Conversely, once we notice a particular kind of relationship within the text, we are more likely to identify the text with the corresponding type. Intratextual concerns alternate with intertextually derived expectations to produce a specific understanding of the text.

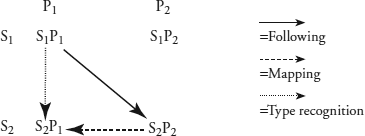

We must therefore modify the transformational matrix, which depends primarily on intratextual relationships, to accommodate the intertextual concerns of typological analysis. In addition to the transformational path to type recognition (constituted by the following/mapping process), we must also take into account the direct type recognition that our intertextual experience encourages us to engage in and which has the power to short-circuit the reading process. We thus recognize that each type involves two separate pathways to the same place. Dual-focus narrative may be represented as in figure 8.7. In the course of reading, we pass through the following stage (solid line), where each succeeding following-unit seemingly presents a new character and action, until such time as apparently different actions are recognized in the mapping process (dashed line) as substantially similar, thus producing the dual-focus mode’s characteristic subject substitution (lower left-hand corner). Other readers may instead jump to the conclusion that the text is dual-focus; this type recognition (dotted line) takes these readers directly to the lower left-hand corner and its expectation of subject substitution within the text. In a similar manner, single-focus narrative exploits the other corner of the matrix, as represented in figure 8.8. The multiple-focus mode is somewhat more difficult to figure. As with single-focus and dual-focus narrative, the transformational method of reaching meaning is doubled by a typological method, but this time the shortcut must be figured as a round-trip voyage, as rendered in figure 8.9.

Within this “square of narrative meaning” a striking variety of complex and interrelated activities are represented—some enacted by characters, others performed by narrators, and still others realized by readers. What makes it possible to describe narrative meaning in this particularly economical fashion is the recognition that dual-focus, single-focus, and multiple-focus types are constituted by the systematic association of a particular following-pattern with a specific kind of transformation.

Schematic representations can be dangerous. While they systematize comprehension and foster understanding of relationships between texts and parts of texts, they necessarily arrest and spatialize phenomena that are hardly stable. Whereas the matrices in this conclusion reduce entire texts to individual two-term relationships, texts themselves introduce innumerable units, piled up, as it were, in depth, with no guarantee that one matrix will resemble another. Thus, in Madame Bovary, we sandwich numerous single-focus matrices, with their characteristic predicate transformations organized around Emma Bovary, between two small piles of similar single-focus matrices, but with predicate transformations organized around her husband Charles. In the same way, single-focus apprehension of Women in Love is tucked into consistent multiple-focus use of each single-focus matrix. Overall perception is thus governed not by a single matrix but by the pattern constituted by many such matrices, joined together and superimposed.

FIGURE 8.7 Dual-focus type recognition.

FIGURE 8.8 Single-focus type recognition.

FIGURE 8.9 Multiple-focus type recognition.

Understanding individual narratives in this way—not just as instances of a type, but as a unique combination of reading principles associated with different types—permits us to recognize a host of important subtypes, depending on the way in which several different reading matrices are organized in full texts. Multiple-focus texts are often formed out of single-focus or dual-focus parts. Seemingly traditional dual-focus love stories written for a female mass market may be interwoven with the single-focus account of the woman’s (supposed) liberation. Emergence of the single-focus nature of a text, as well as identification of the protagonist, may be more or less delayed, thereby prolonging the reader’s freedom to attend in the meantime to other narrative possibilities, or to nonnarrative concerns. Compare the psychological interest forced on the reader by the early single-focus definition of The Red and the Black, The Scarlet Letter, and The Red Badge of Courage, with the availability of Pride and Prejudice for social analysis, because of the slowness with which Elizabeth Bennet takes over the narrative, imposing a single-focus vision on what initially seemed like a multiple-focus account of country society.

The usefulness of a method depends on its ability to isolate and appreciate not only the representative but also the unique, not just the theoretical but also the practical. In the following conclusion I propose to right, in part, the lack of balance in previous chapters. If the method presented here has any value, then it must help us discover not only abstract relationships among ideal narrative types but also real, concrete ties informing not just literary history but daily life as well.