Chapter Two

A Twig of Old England

On May 28, 1812, the cannon at Fort Howe fired a welcoming salute as the Rosina sailed into Saint John after a thirty-one-day passage from Plymouth, England. On board were Major-General George Stracey Smyth, the new president of the Council and commander-in-chief of British forces in New Brunswick, and his family. Smyth had many years of military service, having joined the army at the age of twelve, but no combat experience. While serving as the adjutant of the 7th Regiment of Foot in Gibraltar, he became the protégé of its commanding officer, Prince Edward Augustus, the fourth son of George III. For twelve years, he served on the prince’s staff in Gibraltar, Quebec, the West Indies, and Nova Scotia. When the prince became the Duke of Kent and commander-in-chief of all British forces in North America, he selected Smyth as his senior aide-de-camp and acting quartermaster-general. Smyth’s close association with the duke was rooted in a mutually shared love of music. It can be said with some justification that this was the basis for Smyth’s promotion to general and his appointment to New Brunswick, hardly the best foundation for the challenges he was about to face.

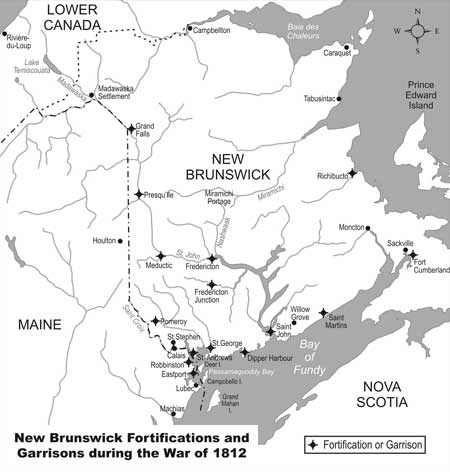

Within three weeks of Smyth’s arrival, word was received that the British Empire was at war with the United States. In reaction to this news, General Sherbrooke set the tone by pronouncing, “The moment has arrived, when the whole strength and soul of our Countrymen are called into action. Through a twig of Old England, we have her spirit, and are engaged in as honourable a cause as the History of the World furnishes.” Smyth immediately met with his Council to determine a course of action for New Brunswick. One-third of the militia was placed on alert, but no militiamen were actually called out because it was planting season and the men were needed in the fields. Instead, all militia commanding officers were directed “to make the best arrangements in your power for assembling the Regiment under your command,” with Smyth stressing the importance of keeping arms and accoutrements in good order. He outlined a concept of defence should the Americans invade that was similar to that of Colonel Gubbins: “I shall recommend, after you have made the best resistance in your power, that you fall back upon the River St John, where you will be supported by an increased population, & be succoured by the whole Military Force of the Country, well appointed in Artillery.” If they should be forced to withdraw, he directed that they bring with them all the provisions possible and ensure that boats were either removed or destroyed. Commanding officers were ordered to establish fire beacons in central locations for the purpose of assembling their militiamen with minimum delay. Strict orders were issued that these beacons were to be properly maintained and, to prevent false alarms, they were to be lit only if an actual invasion occurred. Nor did Smyth neglect the mundane: the firing of morning and evening guns at Fredericton and Saint John was discontinued, “excepting one at nine o’clock from Fort Howe,” in order to save powder for training.

Of considerable concern was the position of the aboriginal people. In early July, with the approval of the Council, Robert Pagan and other magistrates of Charlotte County met with “Indian Chiefs and other Indians in that neighbourhood” to secure their neutrality. The major concern of the aboriginals appears to have been “preventing any injury being done by British subjects to the Indian Chapel erected at Point Pleasant.” An agreement was reached with Francis Joseph, chief of the Passamaquoddy, and Francis Loran, son of the chief of the Penobscot. At the same time, Jonathon Odell, the secretary of the province, met in Fredericton with “a number of the principal Indians of this District” to discuss their position. They made “on the Holy Cross, a solemn and public declaration of their firm purpose to take no part whatever in the war between His Majesty and the United States of America.” In return, they were “assured of peace and protection on the part of [the] Government.” Smyth readily accepted and approved both agreements. The Earl of Bathurst, Britain’s secretary for war and the colonies, was also in complete support of these arrangements, and informed Smyth that the necessity “of engaging them in the Service of Great Britain is not likely to occur.”

Securing lines of communication was another area of concern. The military authorities in Quebec ordered Captain John Grey of the Royal Engineers to survey the route from Quebec City to Halifax. He was tasked to recommend improvements to facilitate troop movements, “to ascertain if any, and how much, of the Route . . . falls within the Territory of the United States” and to map the “Line of Boundary between New Brunswick and the District of Maine.” This was a tall order for a summer’s work. To facilitate the movement of messages along the St. John River, Smyth established small detachments of soldiers between Fredericton and Saint John to act as couriers. They were ordered “to be at all times ready both by day and night to forward despatches both up and down the river.” Smyth also undertook to improve communications with Fort Cumberland on the Bay of Fundy. His aide-de-camp, Captain Thomas Hunter of the 104th Regiment, was directed to reconnoitre a route from Lake Washademoak to the Petitcodiac River. As became his style, Smyth’s instructions were precise and detailed: Captain Hunter was ordered to proceed by bateau up the Washademoak as far as possible, then to determine the location of a portage and distance to a place on the Petitcodiac where a bateau drawing six inches could be launched on waters navigable to Fort Cumberland.

Only minor adjustments were made to the disposition of the British garrison stationed in New Brunswick. The change in status in 1810 from a Fencible regiment to a regiment of the line gave the 104th considerably greater appeal and prestige. Recruiting parties that scoured the countryside throughout New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and into Lower Canada were particularly successful during the winter of 1811-1812, with the result that the regiment’s authorized strength increased from eight hundred to a thousand men. Its peak strength was reached in April 1812 with 63 sergeants, 26 drummers, and 1,008 rank and file. In summer 1812, five and a half companies were stationed in Saint John under the command of Major William Drummond, and battalion headquarters and three companies were located in Fredericton under Colonel Alexander Halkett. Two more companies were stationed in Sydney, Cape Breton, and Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island. After the declaration of war, the garrison at St. Andrews was increased to a half company of about thirty men, and a detachment of eighteen men was sent to garrison Fort Cumberland. The 104th also provided men for a number of outposts, including Sergeant Samuel Bishop and three privates at Grand Falls, a corporal and eight privates at Presqu’Ile (just below present-day Florenceville), and a sergeant and eight men at a newly established post on the Eel River portage.

In addition to the infantry, the New Brunswick garrison included a detachment of the Royal Artillery, which normally consisted of about four officers and forty-five gunners located in Saint John and Fredericton. With the onset of war, artillery detachments were sent to St. Andrews, Fort Cumberland, and, for a period, to St. Martins. In July 1812, Sherbrooke reinforced the garrison with the 1st Company of the 5th Battalion Royal Artillery under the command of Major Henry Phillott. Immediately upon arrival, Phillott set about making suitable arrangements for his four guns, one howitzer, two wagons, two forge carts with limbers, and two ammunition carts. There was no lack of work for the British soldiers; in addition to their normal training and guard duties, they were employed in drilling the militia, providing the engineers with labour for their construction projects, building and improving roads, acting as couriers, and manning gunboats and bateaux.

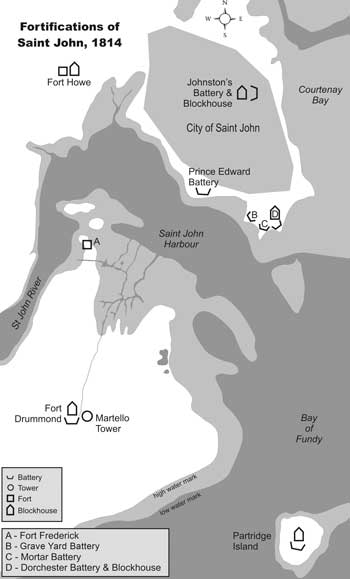

At General Hunter’s direction, the priority assigned to the military engineers was improving the defences of the port of Saint John. Captain Maclauchlan, the senior Royal Engineer in the province, was ordered to move his office from Fredericton to Saint John so that he could monitor the work under way. Fort Howe was considered a key position, but it dated from the American Revolutionary War and was in a state of ruin. Although needing repair, its one-hundred-and-fifty-man barracks was still in use. The site mounted eight cannon and two mortars, but only the stone bombproof magazine, capable of holding seven hundred barrels of powder, was in proper repair. Five gun batteries protected the harbour and, under Hunter’s orders they had recently been strengthened, with further improvements planned. The signal station on Partridge Island, consisting of one gunner and a 12-pounder cannon, lacked defensive works, so plans were made to convert the existing lighthouse into a blockhouse. The main weakness in the city’s defences was to the west, which was vulnerable to enemy attack along the St. Andrews-Musquash Road or by a seaborne force landing at Manawagonish Beach. To cover this key approach, a blockhouse and battery were under construction on Carleton Heights. Since the majority of the labour for this project came from Major Drummond’s detachment of the 104th, it was named Fort Drummond. In addition, old Fort Frederick, first built by Colonel Robert Monckton in 1758, was to be overhauled to cover the St. Andrews Road along the river. Consideration was also being given to erecting “a block House or two . . . upon the height above the town of Saint John to complete the Chain of posts for the defence of the Peninsula” in order to cover the landward approach from the north. This list of projects was a tall order for Maclauchlan, but a new challenge was pending.

Mike Bechthold

General Smyth demanded detailed plans from Maclauchlan for the approved renovations at Fort Frederick, which included a new blockhouse to house thirty men, an estimate of the cost to rebuild the parapet around Fort Howe, and anticipated completion times of all the projects under way. The engineer officer responded promptly, outlining the many challenges he was facing. Rainy weather, the lack of sufficient work parties, and the need to employ the available carpenters on building boats had delayed further work on the gun batteries. He requested permission to hire more carpenters on contract. Adding a chimney to the blockhouse in the Johnston’s Battery was held in abeyance, due to the lack of bricks, but Fort Drummond and its battery were complete, and Maclauchlan requested authority to purchase a stove and other fittings. He reported that one contractor would complete ten boats within the week, but that a second contractor would not complete his five boats on time.

Within days of satisfying Smyth, his local superior, Maclauchlan received conflicting direction from Captain Nicolls, his military engineer superior in Halifax, who held a very different view of both the threat and the requirement. He was bluntly informed that any raid by the Americans against Saint John could be “secured” by the Royal Navy, the existing batteries, and the military forces available. Nicolls questioned the purpose of “a Block House 1400 yards distant” from the town and the usefulness of renovating Fort Frederick, when it was “commanded on all sides.” Instead of expensive defensive works on Carleton Heights, Nicolls suggested signal guns or possibly gun batteries at Musquash and at Manawagonish Beach. He argued that fortifications on Partridge Island made much more sense, “as with a little done to it, it may be held by a small force long after St John is in the possession of the Enemy and rendering that Harbour useless to him.” He clinched his argument by stating that he had General Sherbrooke’s full concurrence in directing “the greatest economy on these works.” Maclauchlan was ordered to find a safe anchorage for small vessels in “ordinary weather” on the east side of Partridge Island that would be protected from an enemy occupying Carleton. Nicolls again emphasized the importance of building a fleet of gunboats and bateaux.

Construction of the Carleton Martello Tower began in 1813 to improve the defences of the harbour of Saint John; it is now a National Historic Site. New Brunswick Museum 1956.43.11

This conflict quickly escalated beyond the two engineer officers. Sherbrooke informed Lord Bathurst that he disagreed with Smyth over defence issues and that “our opinions differed very materially upon this Subject.” As a result, he felt it his duty to order Nicolls “to inspect and report what might appear necessary to be done under the existing circumstances for the protection of that vulnerable part of His Majesty’s Dominion.” As the commander-in-chief of the British forces in New Brunswick, Smyth took umbrage at what he considered interference in his area of responsibility.

Nicolls submitted his twenty-eight page report to Sherbrooke on November 14, 1812, detailing the observations and recommendations “made on the River St John’s, as occurred during my late hasty Journey to Fredericton.” He considered Saint John, with its population of 2,500, “the key of the Province.” In his view, the importance of Fort Howe had “always been greatly magnified”: a hill within nine hundred yards of the fort overlooked its guns, and it neither protected the shipping in the harbour nor the town. He felt that the approaches to the town from the north were well protected by nature, thanks to the St. John River, the Kennebecasis River, “the Rocky Precipices that line their Banks,” swamps, and wilderness. He believed the southern sea approach had been secured with the existing gun batteries and the defences planned for Partridge Island. To the southeast, the approach from Mispec would be guarded “with the cooperation to be expected from the Navy.” However, the eastern side would be extremely difficult to defend because of several isolated heights, each of which required detached and unconnected fortifications. With the forces available, it would be impossible to man them adequately. Nevertheless, if the enemy was prevented from landing in the harbour, the nearest disembarkation point to this approach was Quaco, some fifty miles distant over difficult terrain. Nicolls suggested that this was an unlikely option for an invading enemy and could be left undefended. To the west, Carleton Heights offered a very strong position, with the right flank protected by the St. John River and the left by the Bay of Fundy. If these heights were held, the harbour, town, and sea batteries would be secure and, if necessary, stores, ordnance, and troops could be evacuated without interference. Nicolls proposed strengthening this position with four redoubts connected by abattis. He believed these heights were so important that consideration should be given to adding “a Stone Tower.” Before leaving Saint John, he ordered Maclauchlan to produce an estimate of the cost to undertake this work.

Stone in the Gladstone Cemetery, Fredericton Junction, thought to mark the graves of British soldiers of the War of 1812. Courtesy of Sharon Dallison

Nicolls’s reconnaissance took him upriver as far as Fredericton. This town of four hundred inhabitants was spread out over an open area that could easily be dominated by cannon fire from the surrounding hills. In his view, any attempt to fortify Fredericton “would be an useless expense.” An important route ran up the Oromocto River to a settlement at its forks, where a “bad Road” ran thirty miles through uninhabited woods to the Magaguadavic River and from there to St. Andrews. He felt this frequently travelled road was a likely enemy approach, and recomended the construction of a blockhouse to secure it. On the St. John River, he identified a strategic location called Worden’s, near today’s Evandale, where the river narrowed to between four and five hundred yards. The site was opposite the Saint John-Fredericton road and near the ferry crossing leading to Fort Cumberland. There he recommended the construction of a strong post consisting of a battery of three 18-pounders and a blockhouse with accommodation for a company of infantry. He saw these posts as having both “political” and military value. They could serve as assembly points for the militia during an invasion and “have the Beneficial Effect of giving confidence to the Natives, at a cheap rate, & show them that it is intended to defend every Avenue to the Province as long as possible.”

Nicolls’s major recommendation again emphasized the importance of maintaining control of the St. John River both to defend the province and to protect the strategic route to Quebec City. He identified the requirement for a strong military post at some central location along the river to provide a focal point for all military operations, in addition to providing a secure depot for provisions, ammunition, stores, and vessels. The site he selected was on the high ground on the south side of Washademoak Lake where it entered into the St. John River, halfway between Saint John and Fredericton, with access to the Petitcodiac River and Fort Cumberland. There he recommended the construction of a substantial permanent pentagonal fort.

It is not surprising that Nicolls’s report confirmed and supported his previously held concept of the defence of New Brunswick, which focused on the St. John River Valley. His “hasty Journey” had covered only that part of New Brunswick, and he appeared to have had little time or consideration for conflicting points of views.

Sherbrooke forwarded a copy of the report to Lord Bathurst without delay, noting that he placed great reliance on Nicolls’s judgment and had approved all of the recommendations with one exception. Since the Washademoak military post was to be a permanent establishment and a major expense, it had been referred to the inspector general of fortifications for consideration and approval, which it never received. Nonetheless, the issue of a defensive plan and construction priorities for New Brunswick had been resolved. The plan also appears to have benefited Nicolls’s career: he was promoted to lieutenant-colonel and in October 1814 was appointed commanding engineer for British North America. Maclauchlan, on the other hand, remained a captain stationed in remote New Brunswick. There was another unfortunate result: Smyth remained upset and hurt by what he considered to be high-handed interference and in his future dealings with Halifax he became quite petulant.

Work began immediately on the Nicolls projects. A detachment from the 104th was sent to the fork of the Oromocto River, today’s Fredericton Junction, to secure the area and to assist in construction. Although further work was planned, the blockhouse itself was ready for occupation in July 1813. Control of the road between Fredericton and St. Andrews was further enhanced with the construction of a second blockhouse at the southern end at the Pomeroy Bridge on the east bank of the Magaguadavic River. The post at Worden was built as envisioned by Nicolls and consisted of a three-gun battery with the guns on wooden carriages firing over a parapet. The two-storey wooden blockhouse stood on a hill one hundred and fifty yards behind the battery, with two 4-pounder guns on the second floor. Plans for the recommended stone tower on the Carleton Heights were completed in March 1813 and construction started that season. Because of the shortage of materials and the lack of skilled labour, the tower was not completed until mid-1815, after the war ended. The finished structure is a typical Martello Tower of the period, fifty feet in exterior diameter and thirty feet high, with a tapering rubble masonry exterior wall six feet thick. The Carleton Martello Tower National Historic Site stands today as a legacy to New Brunswick’s involvement in the War of 1812.

During these early days of the war, New Brunswickers’ patriotism received a boost from stirring events occurring outside the province. On August 15, 1812, military headquarters in Saint John announced the electrifying news that Detroit, with twenty-five hundred American soldiers and twenty-five cannon, had surrendered “without the sacrifice of a drop of British blood.” In honour of General Sir Isaac Brock’s brilliant victory, celebrations were held across the province. In Fredericton, a Royal salute was fired by gunboats on the river, accompanied by a feu de joie by the garrison, and in the evening a brilliant ball was given by His Honour the President. Lurid accounts of the American invasion of Upper Canada that followed in the Royal Gazette and New Brunswick Advertiser were clearly designed to inflame public opinion: “We understand from undoubted authority, that the officers and soldiers of the American Army under General Hull, whilst they were in Canada, committed many unheard of depredations. The house of Colonel Baby was pillaged by them and every article in it, even to his last shirt; after pillaging the House and Store of Mr Greger, they wantonly burnt his dwelling house to the ground. They cut down the Fruit-trees in several orchards and gardens and robbed every person who had anything worth their notice.” An article with the heading “A diabolical instance of treachery” recounted an incident in which British officers sent to parley were attacked by an American officer wielding a dagger after the Americans had raised the white flag. More exciting news soon followed. The Duke of Wellington had won a brilliant victory at the Battle of Salamanca in Spain by decisively defeating the Duke of Marmot, a well-regarded French general. The Royal Gazette reported “a Royal salute was fired from Fort Howe interspersed with volleys of small-arms fire from the 104th Regiment. In the evening a grand ball was given at CODY’s [a Saint John hotel], at a very short notice, in honor thereof.” Although it was not realized at the time, this victory proved to be the turning point for the British in the Peninsular War. Then, at the end of October, news arrived of yet another victory: the Battle of Queenston Heights had turned back the second American invasion of Upper Canada. This time, however, the rejoicing was more subdued because General Brock had been killed leading an assault. As the Royal Gazette and New Brunswick Advertiser reported, “though it will be found great and glorious news, and while we rejoice . . . we have to regret the loss of the ever-to-be-lamented Major-General Brock.” Earlier, on June 24, a decisive event in world history occurred that went almost unnoticed in New Brunswick: Napoleon and his Grand Army crossed the Niemen River to launch his fatal Russian Campaign.