Chapter Seven

Adjusting the International Border

It did not take long for dramatic events in Europe to impact North America. Napoleon’s Russian campaign had come to a disastrous end when, of an army of half a million men, only twenty thousand staggered out of Russia’s vastness. In October 1813, before he could recover, Napoleon suffered a major defeat at the Battle of Leipzig. More defeats came as the Duke of Wellington chased the French back across the Pyrenees into France. Allied troops marched triumphantly into Paris on April 6, 1814, and Napoleon abdicated, accepting exile on the island of Elba.

New Brunswickers followed these developments with excitement and much speculation. In October 1813, Harris Hatch of St. Andrews received a letter from a business partner in Glasgow noting that “Bonaparte has had nothing to boast of since opening of the campaign in Germany, in fact the tide seems rather turned against him. Should the allies be successful — the American War will soon be put to an end.” In February 1814, Reverend McColl of St. Stephen received a letter from a fellow minister noting, “Europe approaches her deliverance. For after the loss of the two last Campaigns and two Such Armies — with all their equipment,” it would be unlikely that Napoleon could “bring another to the Field, that will cope with all Europe, united against him — His downfall will of course precede that of Madison’s who has, if possible, been playing the Strangest Game of the two.” Benjamin Crawford of Long Reach, Kings County, noted in his diary on May 30 that there was great “rejoicing” when news of Napoleon’s abdication reached Saint John.

While the public kept abreast of world events, the province’s Legislative Assembly recognized an opportunity. The House of Assembly formed a committee with Council “for the purpose of preparing a humble petition to His Royal Highness the Prince Regent, praying that when a negotiation for Peace shall take place between Great Britain and the United States of America,” that he have such measures adopted “as he may think proper to alter the boundary between those States and this Province, so as that the important line of communication between this and the neighbouring Province of Lower Canada, by the River St. John, may not be interrupted.” The joint petition forwarded on March 5, 1814, carefully explained that the existing boundary established by the Treaty of Paris after the American Revolutionary War intersected the St. John River, the only practical route northward, that it threatened to bisect the Acadian Madawaska Settlement, and that its precise location was in dispute. The advantage of having the British North American colonies “connected by an open and uninterrupted communication, and especially in times of war” would be fully appreciated. It appeared to the Legislative Assembly that, when peace negotiations began with the United States, there would be an opportunity to settle the border in New Brunswick’s favour.

The Prince Regent readily accepted the proposal and, on June 11, Lord Bathurst responded by promising to take the suggestion under consideration. Edward G. Lutwyche, the resident agent for New Brunswick in London, maintained the pressure, urging Bathurst to recover the Passamaquoddy Islands, which the Americans had “surreptitiously” occupied, and suggested that “the river Penobscot presented a natural boundary and would obviate most of the inconveniences to which the British Colonies are now subjected.” The British government reacted favourably, with Bathurst directing General Sherbrooke to occupy that part of Maine “which at present intercepts the communications between Halifax and Quebec.”

How this was to be done was left to Sherbrooke and his naval colleague, Rear Admiral Edward Griffith. The concept of occupying the upper reaches of the St. John River and the Madawaska Settlement was quickly rejected as logistically too difficult. In order to test both American resolve and the defences along the Maine coast, an expedition under the command of Captain Robert Barrie raided the forts at Thomaston and St. George on June 21. Without meeting any serious opposition, the British captured both forts, spiked the guns, and seized four ships loaded with lime and lumber. This easy success provided the reassurance needed to plan more ambitious projects.

The mission of the 40th Regiment of United States Infantry, stationed in Boston, was to protect the eastern coast of New England, including the Maine border, but not until late March 1814 were two companies under the command of Major Perley Putnam assigned to the frontier. Since the Royal Navy controlled the coastal waters, the companies were forced to march the 650 kilometres from Boston. After detaching men to garrison Castine and Machias, Putnam arrived in Eastport at the end of April with eighty men. It was difficult enough to march along the post road during spring breakup; it was impossible to transport supplies, ammunition, and equipment by wagon, so the American authorities had no option but to risk sending them by sea. With a detachment of twelve men under the command of Lieutenant Enoch Manning on board for protection, a supply schooner arrived off Lubec before dawn on April 30, rounded West Quoddy Head, passed through the narrows, sailed by Friars Head, and raced for Eastport. On watch were H.M. Schooner Bream and H.M. Brig Fantome. With the coming of dawn, a patrolling cutter from Fantome, armed with a swivel gun, spotted the American vessel and gave chase. An armed gig joined in, followed by Fantome herself and Bream once anchors had been raised and sails set. Although the town and its fort were in sight, with the British vessels gaining, the American schooner was forced to take the desperate measure of grounding herself on a sand beach south of Eastport. Lieutenant Manning immediately landed his men and placed them in a battle line to protect the grounded ship, while sending to Fort Sullivan for reinforcements. For more than two hours, a stiff firefight ensued between the American soldiers and the British sailors offshore. The British made no attempt to land and, after suffering two wounded, pulled away. Outnumbered and outgunned, an American newspaper reported, Manning “conducted himself in a very handsome manner” and his spirited resistance had saved the supplies. The Saint John City Gazette duly reported, “we understand a large detachment of U.S. troops have been ordered to Eastport.”

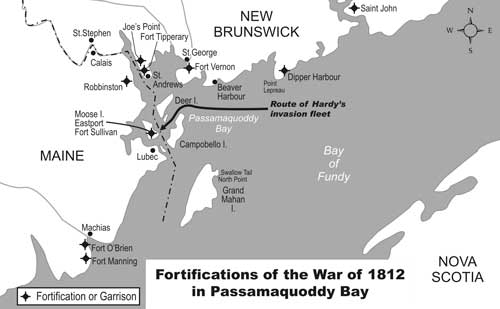

Mike Bechthold

Meanwhile, the British prepared plans to occupy Moose Island. Lord Bathurst directed that the 102nd Regiment, in garrison at Bermuda, be assigned to the task. Captain Sir Thomas Hardy, in whose arms Admiral Horatio Nelson had died at the Battle of Trafalgar, was selected to command the naval contingent. His squadron, also located at Bermuda, consisted of his flagship H.M.S. Ramillies (seventy-four guns), H.M.S. Martin (eighteen guns), H.M.S. Borer (eighteen guns), bomb ketch H.M.S. Terror (ten guns), and four transports. The naval strength of the squadron was estimated at nine hundred sailors and one-hundred-and-fifty-two Royal Marines. Command of the invasion force was entrusted to Lieutenant-Colonel Andrew Pilkington, a senior member of General Sherbrooke’s staff. Orders for the expedition were clear: “occupy and maintain possession of the islands in the Bay of Passamaquoddy.” In addition to the 102nd Regiment, with a strength of seven hundred and two all ranks, were fifty men of Fourth Company, 1st Battalion Royal Artillery, and a detachment of engineers from the Halifax garrison. Every effort was made to keep the expedition and its objective secret. Shelburne, Nova Scotia, was selected as the rendezvous for the forces converging from Bermuda and Halifax. On July 8, less than a day after it assembled, the combined force sailed from Shelburne.

Complete surprise was achieved. At mid-afternoon on July 11, the British fleet was spotted sailing majestically up the passage between Deer and Campobello islands, led by H.M.S. Martin flying a flag of truce. To ensure that no American vessel escaped, H.M.S. Borer had been detached to sail up the Lubec Channel, closing the southern approach to Eastport. There was no time for the American garrison to escape or to call out the 750-man local militia. When Martin anchored off the town, Lieutenant Oates, Colonel Pilkington’s aide-de-camp, went ashore with a flag of truce. He went immediately to Fort Sullivan and delivered the surrender message. Meanwhile, the British warships formed a battle line, with Ramillies and its seventy-four guns within easy cannonshot of the blockhouse.

Oates returned to Martin without receiving a reply, as Major Putnam, the American commander, chose to delay while he heard from a delegation of citizens and held a council of war. When he saw Ramillies clear for action and British troops begin to disembark, he ordered the American flag struck. Within the hour, the 102nd Regiment was ashore, securing the island from attack and taking seven officers and seventy-three men of the 40th US Regiment prisoners of war. Without loss of life or property damage, New Brunswick’s claim to all of the islands in Passamaquoddy Bay had been reasserted.

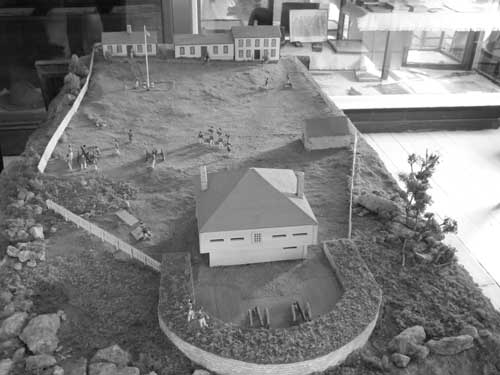

Model depicting Fort Sullivan, Eastport, Maine, in 1812. Courtesy of the Border Historical Society, Eastport

Shortly after seizing Eastport and the rest of Moose Island, the British moved against Robbinston, opposite St. Andrews. Colonel Ulmer had viewed the construction of a British blockhouse and battery at Joe’s Point outside St. Andrews as a serious threat, since it commanded the St. Croix River and was within cannonshot of Robbinston. In response, the Americans built a small earthwork manned by a detachment of the 40th US Regiment and armed with small cannon. On the approach of the British, Lieutenant Manning and his thirty men fled to Machias without firing a shot. At the direction of General Sherbrooke, Lieutenant-Colonel J. Fitzherbert, commanding officer at St. Andrews, informed “the inhabitants of Robbinston and also on the mainland” that the British had “no intention of carrying on offensive operations” against them unless provoked, “as it was their intention only to obtain possession of the islands in Passamaquoddy Bay in consequence of their being considered within our Boundary lines.”

The American newspapers were quick to proclaim the British capture of Eastport a hollow victory, mocking what little had been achieved with such overwhelming force. The British countered by emphasizing that this was not a raid, but a reoccupation. The British saw themselves as liberators, restoring territory usurped by the Americans in 1808 when they built Fort Sullivan. To make a point, the British never used the American name of Eastport, but always referred to the area as Moose Island. In anticipation of a prompt reaction by the Americans to regain the island, the engineer officer, Nicolls, now a lieutenant-colonel, immediately began the task of putting “Moose Island into a respectable state of defence.” He undertook a thorough reconnaissance, concluding that the American fortifications facing the sea were mainly unsuitable for British purposes as the new threat came from the mainland. He produced an ambitious defence plan, which the garrison began to implement immediately. One of these works, the Prince Regent’s Redoubt, still exists on what is now called Redoubt Hill. The expanded and strengthened American fort was renamed in Sherbrooke’s honour.

To emphasize that the British had come to stay, the regimental women and children were landed within hours of the 102nd’s seizing control, and within days a school was established. The custom house was reopened under British direction and, to the great satisfaction of local entrepreneurs, trade resumed. Few restrictions were placed on the inhabitants of Moose Island and all existing municipal laws designed to enforce public order were retained. However, all adult male citizens were required to swear allegiance to the British Crown or leave the island within seven days. On July 16, two-thirds of the male population, a total of 162 men, swore to “bear true and faithful allegiance to His Majesty George the Third . . . and his heirs . . . and . . . not either directly or indirectly . . . carry arms against them or their allies by sea or land.” Within two weeks, the British invasion force split up. Captain Hardy sailed off to raid Stonington, Connecticut, the Royal Artillery company left for Saint John, and a 153-man detachment of the 102nd left to garrison St. Andrews. Lieutenant-Colonel John Herries and approximately six hundred men of the 102nd remained on Moose Island as the garrison.

Graves in the Hillside Cemetery of two British officers who died during the British occupation of Eastport in the War of 1812. Courtesy of Sharon Dallison

Before long, reinforcements from Gibraltar under the command of Major-General Gerard Gosselin arrived in Halifax, giving Sherbrooke the resources he needed to carry out his orders to secure the border. With the full concurrence of Admiral Griffith, Sherbrooke informed Lord Bathurst that “the most desirable plan” would be “for us to occupy Penobscot with a respectable force, and to take that river (the old frontier of the State of Massachusetts) as our boundary.” A substantial force assembled in Halifax, composed of the 29th, 62nd, and 98th Regiments, two companies of riflemen from the 7th Battalion, 60th Regiment, and a company of the Royal Artillery, totalling some two thousand five hundred experienced veterans. Griffith had under his command H.M.S. Dragon (seventy-four guns), H.M.S. Endymion (fifty guns), H.M.S. Bacchante (thirty-eight guns), H.M.S. Sylph (eight guns), and ten transports. Because of the importance of this expedition, Sherbrooke himself assumed command. Again, every attempt was made to maintain secrecy; however, as is its wont, the press was alert. Two weeks before the expedition departed, the New Brunswick Courier reported that, “when a sufficient number of troops arrive on the coast, it is probable that a party of them will occupy that part of the district of Maine between Penobscot and the St John’s rivers.” Fortunately, the American authorities overlooked this newspaper article.

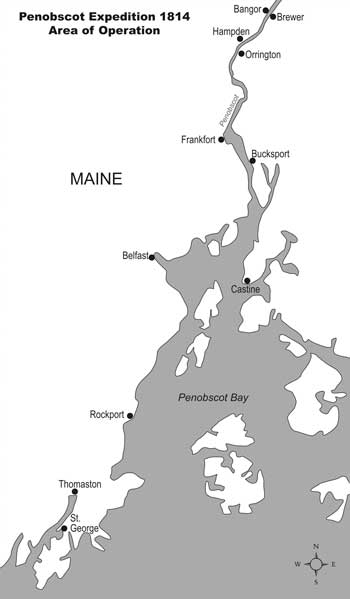

On August 26, the expedition sailed from Halifax. The capture of Machias was the first objective, to be followed by occupation of the Penobscot. En route, it was intercepted by H.M.S. Rifleman with the exciting information that a crippled American frigate, the U.S.S. Adams, had just sought refuge in the river. The opportunity to eliminate one of the few remaining ships of the U.S. Navy could not be ignored, and the plan was immediately adjusted.

Early on September 1, the expedition appeared off Castine, located on a peninsula at the mouth of the Penobscot River. Despite its strategic location, the town’s defences had been neglected. The Revolutionary War fortifications had been abandoned and its new defences were based on a small redoubt and a half-moon battery armed with four 24-pounder and two 12-pounder cannon and a garrison of forty regulars of the 40th US Regiment under the command of Lieutenant Andrew Lewis, and ninety-one militiamen from Bucksport under Lieutenant Henry Little. To satisfy honour, Lieutenant Lewis refused the British demand to surrender and fired a single random volley from his cannon. He then hastily spiked the guns, blew up the powder magazine, and fled. The speed of the departure of the regular soldiers was exceeded only by that of the Bucksport militia. Unaware the Americans had left, the 98th Regiment landed, secured the isthmus to the mainland, and took possession of the town and its fortifications. The British had gained control of the strategic entrance to the Penobscot River without bloodshed.

The Adams was now trapped, and Sherbrooke and Griffith went about the task of locating and eliminating the American frigate in a thorough and professional manner. To isolate the area of operations, the 29th Regiment minus its two flank companies, along with Bacchante and Rifleman, were dispatched to occupy the town of Belfast, located on the west bank of the Penobscot River. This move cut the post road from Boston through Portland to Bangor, thus preventing the forwarding of any American reinforcements. Belfast was occupied and held for four days without any opposition. Meanwhile, a combined naval and military force, consisting of seven hundred soldiers with light field guns, a Congreve rocket detachment, and several small naval vessels, was formed under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Henry John and Captain Robert Barrie R.N. to sweep up the river to locate the Adams. They set out in the late afternoon of September 1 on the high tide, reaching Bucksport at dusk. After discovering two hidden brass cannon, they camped for the night.

Mike Bechthold

The next day, the British made slow progress, impeded by fog and their ignorance of the river’s treacherous currents and shoals. By mid-afternoon they reached Frankfort, only to learn that the Adams was located at Hampden, protected by heavy guns and a force reported at fourteen hundred men. Before the British moved on from Frankfort, they detected the Bucksport militia fleeing from Castine, making their way north along the east bank. A detachment was sent across the river and a skirmish ensued. One American was killed and two wounded, but more important, these troops were prevented from reinforcing Hampden. Lewis and his regulars had already reached the Adams, but local scuttlebutt claimed that the militiamen had been delayed because their officer had “dallied” the night before with a lady friend. The British pressed on to Bald Head Cove, five kilometres south of Hampden, where an American picket was driven off, and the British camped for the night.

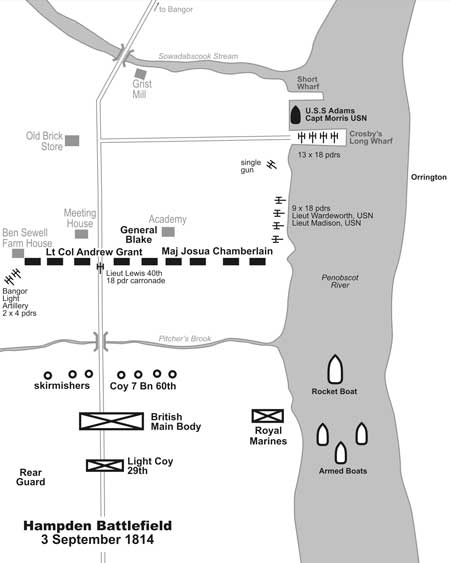

Once Captain Charles Morris of the Adams, a respected and experienced officer, heard of the British arrival at Castine, he prepared for action by removing the cannon from his ship. Nine 18-pounders were placed along the riverbank three hundred metres downstream from the Adams, others were sited on a wharf looking down river, and one covered the gap between the two positions. Morris then notified Major-General John “Black Jack” Blake, the local militia commander, of the threat, who immediately ordered out the 3rd and 4th Regiments of the 1st Brigade, 10th Massachusetts Militia. Unfortunately, a difference of opinion developed on how and where the British should be stopped; when the militiamen reported for duty, there was a lack of direction, and confusion ensued. No action was taken to prepare for the pending battle, and the men remained idle during a long, wet, cold night. At dawn, Blake drew up his men in a line of battle along the crest of Academy Hill, with the left flank on the river, protecting the naval guns, an artillery battery of a 18-pounder carronade and two 4-pounders covering the high road and bridge in the centre, and the right flank extending west of the road. On the field were 761 Americans, mainly ill-equipped and poorly trained militiamen, backed by 150 experienced sailors from the Adams crew. Blake had selected an excellent position on a low ridge with Pitcher’s Brook to the front, crossed by a single bridge, but it would soon be regretted that the available time the evening before had not been used to entrench the site.

The British had had an uncomfortable night too, and heavy fog delayed their departure. The riflemen of the 60th Regiment formed the advance guard, while the Royal Marines moved along the riverbank and the ships kept pace in the river. The British advanced slowly, led by Tobias Oakman, a local man pressed into service as a guide. Two hours later, the skirmishers became engaged. The American militiamen reacted by firing into the fog, while their cannon targeted the bridge. With the Congreve rockets firing overhead and the naval ships engaging the American cannon on the riverbank, Colonel John directed his infantry across Pitcher’s Brook, formed a battle line, and ordered a “double-quick” bayonet charge. The American centre broke immediately, followed by the units on the flanks. With the militia gone, Captain Morris had no choice but to blow up the Adams and make for safety. In less than an hour, the Battle of Hampden was over.

The cost of eliminating the U.S.S. Adams was two British killed and eight wounded. The Americans suffered one killed, eleven wounded, and eighty prisoners taken, along with all the cannon and forty barrels of powder. Captain Barrie complained, “the enemy was too nimble for us and most of them escaped into the woods.” In addition, two American civilians were killed: the guide Oakman died in the first burst of fire and William Reed of Orrington was unlucky enough to be hit by a stray shell while watching the battle from his doorway. The graves of the two British casualties, Private Peter Bracewell of the 29th Regiment and Seaman Michael Cavernaugh, are marked by a stone in the Old Burying Grounds behind the Hampden Town Hall, which was presented by the Lord Beaverbrook Chapter of the Daughters of the British Empire. The local branch of the American Veterans of Foreign Wars faithfully place Union Jacks on the marker every Memorial Day. Regrettably, the name and location of the gravesite of the American casualty is unknown.

Leaving two hundred men to hold Hampden, the British immediately made for Bangor by land and water. Outside of town, they met townspeople with a flag of truce and a request for terms. The only term offered was unconditional surrender, which was accepted without hesitation. The British troops marched into town with flags flying and drums beating. That night, some “jollification” was reported, which the citizens viewed as drunken and disorderly conduct. The next day, General Blake appeared and formally surrendered two hundred of his militiamen, who were immediately paroled. After burning fourteen vessels, taking six as prizes, and obtaining a bond of $30,000 for the safe delivery of four unfinished vessels still in the stocks, the British returned to Hampden.

When the citizens of Hampden complained of mistreatment, Captain Barrie coldly stated, “my business is to burn, sink and destroy. Your town is taken by storm, and by the rules of war, we ought to lay your village in ashes and put its inhabitants to the sword.” In his view, therefore, they had no grounds to complain! Prisoners were taken, some public buildings were burned, the sixteen-gun armed merchantman Decateur was seized, and two other merchantmen were burned. Some of the Adams’s cannon were destroyed and others carried off. Also a $12,000 bond was taken for unfinished vessels on the stocks. By September 9, all the British were back in Castine. Behind them, they left an embittered population, but the resentment was directed largely toward General Blake for his incompetence and the Boston authorities for failing to protect them — resentment that was to simmer and play a role in the creation of the new State of Maine in 1820.

Stone in the Old Burying Ground marking the graves of the two British dead from the Battle of Hampden, September 1814. Courtesy of the Hampden Historical Society

Meanwhile, Sherbrooke and Griffith made it clear that this had not been a raid; rather, the British had come to stay. In a joint proclamation, they announced the intention of retaining possession of the country lying between the eastern bank of the Penobscot River and Passamaquoddy Bay. Arrangements were made for a provisional government, mainly by the expediency of retaining American civil officials in the offices they held prior to the occupation. Almost immediately, the economy in Castine grew exponentially. Merchants from St. Andrews, Saint John, and Halifax relocated and transformed the town into a major forwarding depot from which to continue their trade with New England. Hundreds of wagons made their way across Maine, evading American authorities, while scores of coastal vessels with equal skill evaded both American and British customs officials. On September 18, Sherbrooke and Griffith returned to Halifax, leaving General Gosselin in charge with half the troops and two warships. Work began immediately on improving Castine’s defences. Fort George, the old British fort from the American Revolutionary War, was reconstructed, the American half-moon battery was rebuilt, two large redoubts were constructed facing the mainland, and, innovatively, Castine was turned into an island by digging a defensive canal across the isthmus. All American males over age sixteen were required to swear an oath of neutrality or leave. A large majority opted to take the oath. There was little tension and no resistance, as Gosselin was held in high regard. He was a wise choice, as he had a compromising personality and maintained tight control over his soldiers. A widespread acceptance developed in the community to the anticipated political change implicit in the British occupation.

Before Sherbrooke left Castine, Colonel Pilkington was despatched with the 29th Regiment, along with riflemen from the 60th Regiment and a detachment of the Royal Artillery, to capture Machias. He landed at Bucks Harbor, sixteen kilometres south, and made a daring night march to Fort O’Brien, achieving complete surprise, driving off the picket, and capturing the fort intact from the rear. The American garrison of seventy regulars of the 40th Regiment and thirty militiamen retreated so rapidly that Pilkington complained he was unable to take many prisoners. An hour later, Machias was occupied without resistance. Shortly after, Brigadier-General John Brewer, commanding the 2nd Brigade, 10th Massachusetts Militia, submitted and promised not to bear arms or take any hostile action, while the civil authorities and leading citizens agreed to submit to all direction from the British. Pilkington informed Sherbrooke that Britain had complete control of northern Maine. The New Brunswick Legislative Assembly’s wishes had been fulfilled: the border with the United States had been expanded westward to the banks of the Penobscot River.