Chapter Eight

In the Eye of the Storm

On September 12, 1814, news of the British capture of Castine and General Sherbrooke’s proclamation taking permanent possession of Maine from the Penobscot River northward reached Saint John. The occupation of northern Maine provided a buffer for New Brunswick and removed any threat of invasion. This feeling of security and the prospect of ultimate victory was further enhanced when the City Gazette reported two weeks later that an advance guard of three thousand troops was embarking in Europe for North America under the command of one of the Duke of Wellington’s most experienced and able generals. This news followed an earlier report that seven transports had left Bordeaux, France, with fifteen hundred war-hardened reinforcements.

New Brunswickers’ sense of relief was moderated, however, by the intensity of the fighting in Upper Canada. The Americans were making a third attempt to conquer this exposed province, this time under the command of competent leadership and with trained troops. The American offensive began with the uncontested capture of Fort Erie, which had been under the command of Major Buck, a popular figure when he had commanded at St. Andrews. It therefore came as a shock when General Prevost severely rebuked him, saying he “is greatly aggravated by the disappointment and mortification he has experienced in learning that Fort Erie, entrusted to the charge of Major Buck, 8th or King’s Regiment, had surrendered on the evening of the 3rd inst. by capitulation, without having made an adequate defence.”

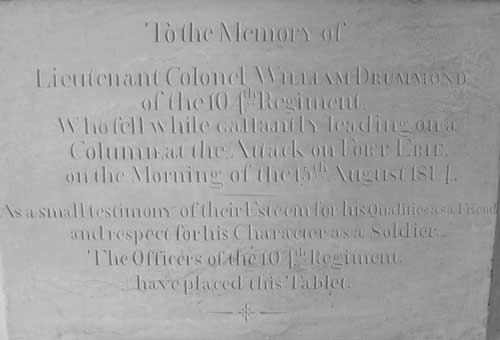

Plaque in memory of Lieutenant-Colonel William Drummond of the 104th, killed in action at the Battle of Fort Erie, August 1814, erected by the officers of the regiment; located in the vestibule of St. Anne’s Chapel of Ease, Fredericton. New Brunswick Military Heritage Project

The Battle of Chippawa followed, at which British regulars were beaten for the first time in this war by Americans in a stand-up fight. Three weeks later, they were fought to a draw at the Battle of Lundy’s Lane, the bloodiest contest of the war. These events on the Niagara frontier were closely watched by New Brunswickers, as so many of their sons and friends were involved. A family member in Saint John wrote to Lieutenant Thomas Leonard of the 104th Regiment expressing their concern: “I cannot tell you my dear Tom how very anxious and uneasy we are about you.” Margaret McLaggan of the Nashwaak River wrote to her daughter and son-in-law, a sergeant in the Glengarry Light Infantry, saying, “I am sorry that the war is not likely to be over this season . . . The British has taken possession of a considerable part of New England without much loss . . . We have no trouble here with the war . . . Henry White’s daughter and other women of the 104th came here this summer. I wish you would do the same. I know how hard it is to follow the army with a child carrying.” Then came news of a disastrous British assault on the American-occupied Fort Erie. New Brunswickers grieved, as the two flank companies of the 104th Regiment had been heavily involved, losing fifty-four men of the seventy-seven engaged. The hardest loss, though, was that of the beloved and respected commanding officer of the 104th, Lieutenant-Colonel William Drummond, killed leading the assault on the northeast bastion. In his memory, citizens placed a plaque, now located in the entrance vestibule of St. Anne’s Chapel of Ease in Fredericton, “as a small testimony of their esteem for his qualities as a friend and respect for his character as a soldier.”

Meanwhile, the Royal Navy had carried its war farther south along the Atlantic coast, away from the Maritime provinces. In spring 1814, Admiral Warren had been replaced by the more aggressive Vice-Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane. With the full support of the Admiralty, Cochrane, while still targeting the Chesapeake Bay area, extended the blockade to the entire east coast of the United States and began raiding operations along the New England coast, bringing a determination and ruthlessness to naval operations not seen before. He made no attempt to conceal his dislike of Americans, whom he described as a “sad despicable set.” His orders were to “lay waste” to American towns and on no account to spare harbours, magazines, shipping, or government property, although unarmed inhabitants were to be left unharmed and tribute might be levied to safeguard private property. What remained of the US Navy was in no position to resist, and Americans living along the Atlantic coast felt vulnerable, as reported in a letter from Wiscasset, Maine, published in the City Gazette: “we are constantly in a state of alarm. In addition to the militia, and artillery, every citizen has become a volunteer.” The Royal Navy brought the war to the doorstep of the United States by raiding, capturing, and destroying with impunity. Its actions culminated in a raid on Washington and the burning of, among other public buildings, the Executive Mansion. News of the capture of Washington was received with considerable excitement with the New Brunswick Royal Gazette gloating that “this is doing business as it ought to be done,” while the City Gazette reprinted President Madison’s report on the capture under the inflammatory caption, “The yelping of a Cur, at being whipped out of his kennel!” When the Americans rebuilt the president’s residence, they painted the building to conceal the burn marks on the stone; the residence was thereafter called the White House.

Vice-Admiral Sir Alexander Inglis Cochrane, an energetic and aggressive naval officer appointed commander of the British North American Naval Station in 1814. Library and Archives Canada C-009709

While hostilities raged in distant Upper Canada and south along the Atlantic coast, local military activities kept the war prominent in the minds of New Brunswickers. In spring 1814, Colonel Darrell, the commanding officer of the 99th Regiment, established his headquarters in Saint John, and on July 25 the Grenadier Company of the regiment arrived on the transport Royalist as replacements for the 8th Regiment. Lieutenant Leonard’s sister noted in a letter to him that, “for our exchange of Regiments I think we have been fortunate. The 99th took very well after they have given the usual introduction ball, which the 8th dispensed with.”

But not all military-civilian relations were cordial. In December 1814, the City Gazette reported, “The recent shameful conduct of several of the Petty Officers and Seamen of the Navy, demands the serious consideration of the Police of our City. Gangs of Men-of-War-men, armed with swords, bludgeons, and other unlawful weapons, prowl about our streets, and insult, with impunity, our peaceable citizens.” The newspaper provided details of several violent incidents, including a report that, “on Saturday evening another Gang, entered with violence, the houses of two or three respectable persons, in one of which were none but females.” These tensions were compounded by economic setbacks. When Mayor William Campbell of Saint John complained about a “great scarcity of flour by the failure of the usual sources of supply,” General Sherbrooke petulantly replied that this was the result of the successful blockade of the American coast, a necessity of war, and suggested that the local merchants use their initiative and purchase flour in England, where it could be obtained at a moderate price. On occasion the news had a direct economic impact, as with the September report that the Saint John-owned brig Brothers under the command of Captain Rawleigh, eight days outward bound for Liverpool, had been captured and burned by the American sixteen-gun privateer Grand Turk.

The establishment of the Penobscot River as the international boundary had an effect all along the old border. At the start of the war, a detachment of one sergeant, one corporal, and twelve privates from the 104th Regiment had established a post at Meductic in order to control the Eel River portage route into the United States and to protect the local residents. The detachment was under the operational control of Major Daniel Morehouse, the commanding officer of the Second Battalion, York County Militia, a prominent and respected citizen of the region. An amiable agreement had been quickly established with the residents of the isolated community of Houlton, Maine: “as long as the settlers remained neutral they had nothing to fear.” As the American threat decreased, so too did the size of the detachment; however, Major Morehouse’s command continued to play a useful function. Protection and assistance were provided to the vital courier service to Quebec, and Morehouse provided accommodation to troops making the winter march to Upper Canada. Today, the Morehouse home is one of the icons at Kings Landing Historical Settlement.

By late in 1814, the Meductic detachment was under command of Daniel’s son, Ensign George Morehouse of the New Brunswick Fencibles. Since Houlton was now considered British territory, on January 7, 1815, General Smyth ordered Ensign Morehouse to proceed there and administer the oath of neutrality to the inhabitants. In his report, Morehouse noted that Houlton had a population of about seventy, of whom seventeen were males over age sixteen and all of whom took the oath. In addition, Morehouse took the initiative of administering the oath to fourteen American citizens living along the St. John River between Meductic and Presqu’Ile. Circumstances had also changed along the St. Croix River, where, less than four months earlier, Colonel Fitzherbert had promised that the British had “no intension of carrying on offensive operations” in the region. On October 20, he was ordered to take possession of Robbinston with a detachment of the 102nd Regiment. In consequence, the British flag was raised over the abandoned American earthwork and renamed Fort Smyth.

The home of Major Daniel Morehouse, commanding officer, Second Battalion York County Militia was used for overnight accommodation in the winter marches up the St. John River during the War of 1812. Kings Landing Historical Settlement

With their war effort focused on the conquest of Upper Canada, Americans acted with ambivalence to the occupation of northern Maine. There were few signs of hostility among the inhabitants in the occupied area, and no attempt was made to interfere with the British garrison. A report datelined Boston September 26, 1814, noted that all was quiet in Castine, all resistance east of the Penobscot had ceased, and “deputations from the several towns were daily coming in to signify to the British commanders their assent to the terms which were proposed to the inhabitants of that tract of country.” To the frustration of the Madison administration, an embarrassing number of New Englanders considered the British troops and the blockading British ships not as enemies, but as a ready market where transactions were completed with hard currency. To the great relief of the British military and navy, the bulk of their supplies were provided by American farmers, fishermen, and businessmen. Discussions concerning a seaborne counterattack to reclaim Castine had been held in the Massachusetts legislature, but they came to nothing. The state’s governor, Strong, continued to oppose the war and to feud with federal military authorities over their repeated requests for support. Eventually, however, the Royal Navy’s depredations prompted him to call a special session of the Massachusetts legislature, during which a committee concluded that, “dishonored and deprived of all influence in the national councils, this state has been dragged into an unnatural and distressing war, and its safety, perhaps its liberties, endangered.” Massachusetts sent invitations to other disaffected New England states to discuss their common grievances and possible corrective action. At the resulting Hartford Convention, held in December 1814, heated public debate included consideration of secession from the union. While attention was focused on the Hartford Convention, Strong took the extraordinary step of dispatching a clandestine state mission to Halifax to explore with General Sherbrooke the possibility of a separate settlement with the British; indeed, Nantucket Island had already negotiated a cessation of hostilities. Fortunately for the future of the United States, however, peace talks were already under way.

By mid-1814, it was clear that the war was not going well for the United States. Its objective of conquering the Canadas had failed, large numbers of British reinforcements were arriving in North America from Europe, the British naval blockade had eliminated all overseas trade, the national debt had risen from $45 million to $127 million, and unrest in New England had led to talk of secession. Watching these events with interest, New Brunswickers anxiously discussed the possibility of peace. In a letter to his family on the Nashwaak River, Sergeant Alexander McMillan wrote: “There are great expectations of Peace. Troops going up Country every day and 2 Generals and 9 thousand men on their way now, up from Quebec. We hope with God’s blessings that matters will soon be decided.” Although speculation was rife, the general public was unaware that, as early as March 1813, Tsar Alexander I of Russia had offered to mediate the conflict. Madison accepted the offer and immediately sent a delegation to Europe, but Britain was unwilling to involve Russia, and the offer came to naught. It was not until July 1814 that the United States accepted the British proposal of direct negotiations, and a month later representatives of the two countries met in the Flemish city of Ghent.

Depiction of the signing of the Treaty of Ghent, ending the War of 1812, Christmas Eve 1814; Admiral Sir James Gambier shakes hands with the American John Quincy Adams while the other negotiators and staff look on. Courtesy of Library and Archives Canada C-005966

The appointment of Admiral Lord James Gambier as head of the British delegation at Ghent, supported by William Adams, a well-known maritime law expert, ensured that vital British naval rights would not be compromised. To the satisfaction of British North Americans, the issue of the international boundary was forefront in the initial negotiations. New Brunswickers hoped that errors made by the Treaty of Paris of 1783 would be rectified by the acquisition of all the islands in Passamaquoddy Bay and the provision of a more secure route to the St. Lawrence River. It was not to be. The American delegation, consisting of experienced, determined, and skilful negotiators, contested every issue, debated at length, and appeared willing to negotiate forever. The British, on the other hand, were anxious to end this annoying secondary conflict, which deflected their energy and resources away from their main focus, the upcoming Congress of Vienna and the future of Europe. In addition, the British government was under considerable public pressure to end the war; after twenty-two years of conflict, the country was war weary, the national debt was massive, and its citizens were suffering under a heavy tax burden. What finally broke the deadlock was Tsar Alexander’s proposal, with the concurrence of Prussia, to transform the Duchy of Warsaw into the Kingdom of Poland with himself as king. This created the potential for a diplomatic rupture at Vienna and the renewal of hostilities. This threat prompted the British to bring the negotiations with the Americans to a quick conclusion. Consequently, few of the contentious issues were resolved — indeed, most were simply removed from the table — and, on Christmas Eve 1814, the two sides signed the Treaty of Ghent.

The treaty would not become effective until ratified by both governments, which the US Senate did on February 17, 1815. News of the American acceptance reached London a month later. The timing could not have been more propitious as, four days later, Napoleon escaped from Elba and embroiled Europe in his famous Hundred Days campaign. Reinforcements scheduled for North America were immediately redirected to the new challenge posed by the “Little Corporal,” which culminated in his final defeat at the Battle of Waterloo in June.

News of the peace treaty did not take long to reach New Brunswick. On February 19, Benjamin Crawford, a farmer on Long Reach, Kings County, noted in his diary, “Heard of peace with America.” The citizens of Saint John lit up their houses and gathered in the centre of town to devour roast oxen in celebration. Relief at the restoration of peace was moderated, however, by the terms of the treaty. In essence, it restored everything to what had prevailed at the start of the war. The treaty made no mention of maritime grievances, including the demand for sailors’ rights and free trade, which had induced the United States to declare war. More significantly for New Brunswick, the hotly debated changes to the international boundary were reduced to the status quo ante bellum: as Article 1 decreed, “all territory, places, and possessions whatsoever, taken by either party from the other, during the war . . . shall be restored without delay, and without causing any destruction, or carrying away any of the artillery or other public property originally captured.” Areas where the boundary remained in dispute were referred to special commissions to be appointed later. In accordance with the treaty, on April 25, 1815, British troops evacuated Castine, restoring the Penobscot River Valley and northern Maine to American control, and re-establishing the St. Croix River as the international boundary. The only exception was Eastport on Moose Island, which the British continued to occupy pending the decision of a yet-to-be-established special commission. To the regret of New Brunswickers, the border with Maine would not be resolved for another three decades.