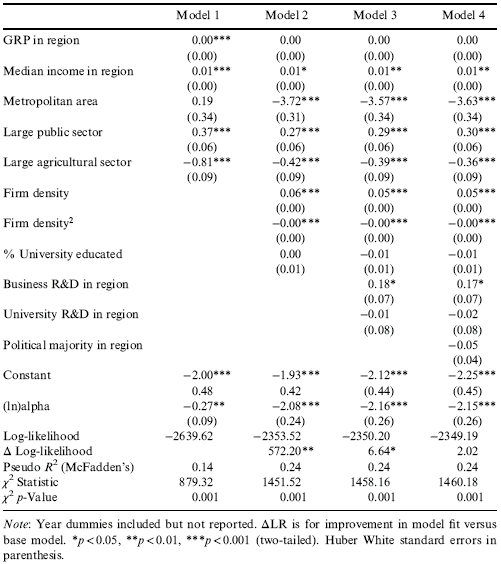

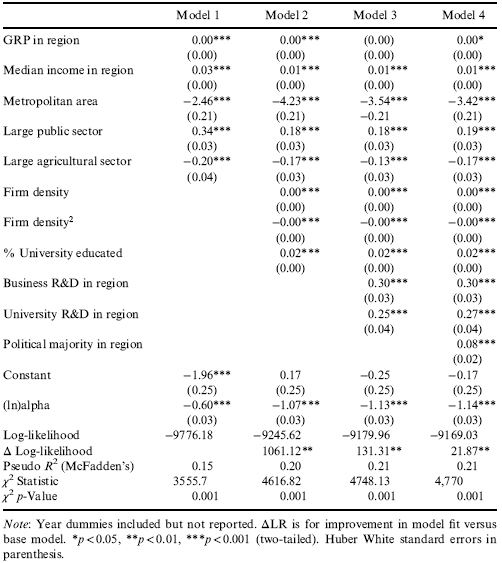

METHODS

Research Setting

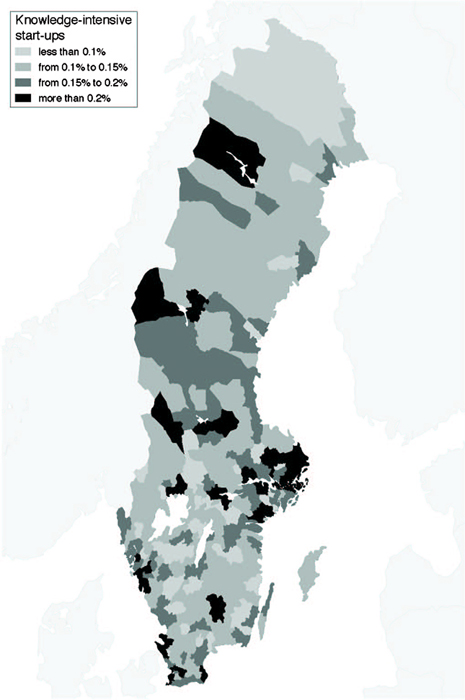

The empirical setting for our test of these theoretical arguments is Sweden; a relatively small but geographically dispersed nation with a high variation in economic activity. In Sweden, famous cases of clusters or industrial districts consist of biotechnology firms in Copenhagen-Lund and Uppsala-Stockholm (Wennberg & Lindqvist, 2010). The Stockholm area is particularly dynamic. Similarly to other European cities like Copenhagen, Berlin, and Munich Stockholm has evolved from a city driven by public institutions, education, and research to a metropolitan area increasingly driven by entrepreneurship in a large variety of economic sectors (Acs, Bosma, & Sternberg, 2008). In 1994, the year in which our investigation initiates, the greater Stockholm area comprised 30% of Sweden’s GNP and the annual start-up rate of knowledge-intensive firms per inhabitants ranged between 0.3% and 0.6% in the largest Stockholm municipalities, more than three times the national average. Also in real counts of knowledge-intensive start-ups, the sheer size of Stockholm’s economy and population makes it stand out as an entrepreneurial hotspot (see Appendix A and Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Municipalities with Highest Relative Entry Rate (Shaded) 1994–2002.

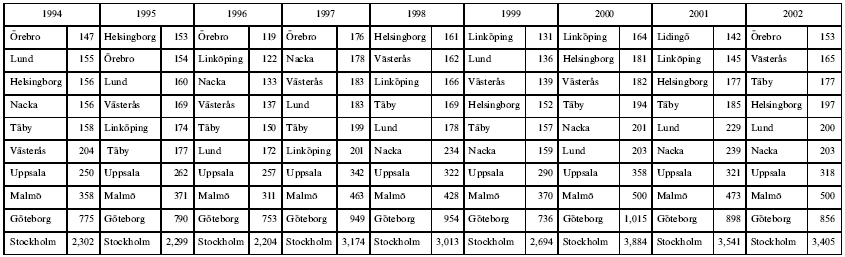

In Table 1 it is interesting to note that a number of much smaller regions also have a relatively high start-up rate. Among these regions are both affluent areas with a large share of Stockholm expatriates and seasonal workers (Åre and Båstad) but also much smaller rural areas that are neither economically affluent nor dominated by industrial production. In particular, some municipalities in the rural area of Dalarna (in particular Malung in 2001) are found among the top municipalities in knowledge-intensive start-ups. Dalarna has been depicted as a region with a weak industrial manufacturing base and also lacking a knowledge-inducing sector of colleges and universities. Our data shows that the average level of education in these municipalities is quite low and the number of engineers and scientists in the lower 3rd percentile of the whole country. What, then, can explain the high rate of start-up activities in these regions? One potential explanation is local culture and another is political regulations (Giannetti & Simonov, 2009). The public government in these municipalities switched on average two times during the 1990s, indicating that significant changes in sociopolitical governance structure might have occurred. It should be pointed out that this association between political governance and entry rates is correlated but not necessarily causal. That is, it might not be the shift in political governance to a right-wing majority but rather a trend toward deregulation or other pro-market forces that are indirectly associated with political governance, that are the true determinant for the higher entry rates in municipalities such as Malå, Malung, Ljusdal, and Leksand in the mid-1990s. Another potential explanation pertains to the local culture. According to Johnson’s (2008) study of entrepreneurial regions, the socioeconomic heritage in Dalarna of low incomes and a “do it yourself” culture of mixed farming, seasonal work, and home-based small manufacturing has led to a strong tradition of small business activities in Dalarna compared to other similar regions. In such areas, the tradition of combining employment and self-employment as a mean to make enough earnings has again become more important as the industrial economy is gradually replaced by a knowledge-intensive economy (Folta, Delmar, & Wennberg, 2010). Table 1 also shows some striking examples of entrepreneurial municipalities. However, with the exception of, for example, Dalarna, the main urban areas of Malmö, Göteborg, and in particular Stockholm dominate the picture for knowledge-intensive start-ups. The predominant role of Stockholm as an engine of entrepreneurial growth in Sweden can be generalized to other contexts with the help of theoretical models of economic geography and organizational ecology depicted above. Because agglomerations are often much higher in urban areas, the increasingly “spatial” nature of entrepreneurship and especially growth-oriented entrepreneurship mean that the level of ambition in entrepreneurship rises where competition and local growth-prone institutions are existent (Autio & Acs, 2010). This can be seen around the world through the increasing rates of entrepreneurship in urbanized region. This pattern is strongly accentuated in Sweden where a few metropolitan areas, in particular Stockholm, comprise a large and increasing share of entrepreneurship and economic growth. The benefits of urban size for new firms are many: Large urban economies bring with them greater industrial and occupational diversity that facilitate the transfer of new innovations across industries (Jacobs, 1969; Rosenthal & Strange, 2005).

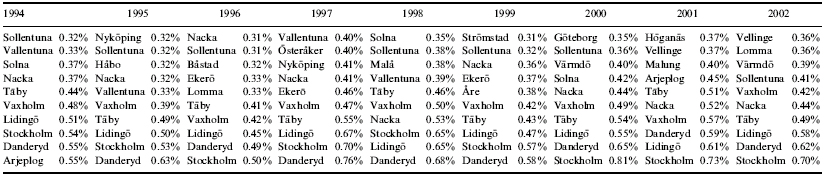

Table 1. The 10 Municipalities with Highest Relative Entry Rate 1994–2002.

Note: Entry rate computed as start-up rate of knowledge-intensive firms per number of inhabitants.

Data

Our empirical analysis focuses on how characteristics of the economic milieu of regions influence firm births. For this purpose we employ the unique database maintained by Statistics Sweden: RAMS, which provides yearly data on all firms registered in Sweden. We used RAMS to sample all privately owned firms started between 1994 and 2002 in the knowledge-intensive sectors. Three considerations motivated the time period we chose: (1) In Sweden the years 1990–1993 was a time period with the lowest economic activity since the Great Depression. Because we are interested in how variation in contextual factors across regions affects firm births, basing our analysis on such a period could taint our results. (2) Several years of start-up history are needed to avoid cohort effects. For analyzing the contextual influences on firm births it is necessary to create a measure of births at the regional level. We did this by aggregating all yearly start-ups to the municipality level for each of the years 1994–2002 by summing all firm entries into a total value for the municipality. A value of 23 thus implies that 23 births occurred in municipality i at time j. We use a slightly narrower time frame than in preceding research since some of the important predictor variable were only available from 1994 onwards. (3) Several of our predictor variables were not available until 1994. The knowledge-intensive sectors in our sample constitute the complete set of high-technology manufacturing or knowledge-intensive service sectors, according to Eurostat and OECD classifications of such sectors (Götzfried, 2004). In total, 22 five-digit industry codes equivalent to the U.S. Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) system are included in the sample, comprising roughly 33% of the Swedish economy but over 40% of employment. See Appendix B for a complete list of sectors included.

Dependent Variable

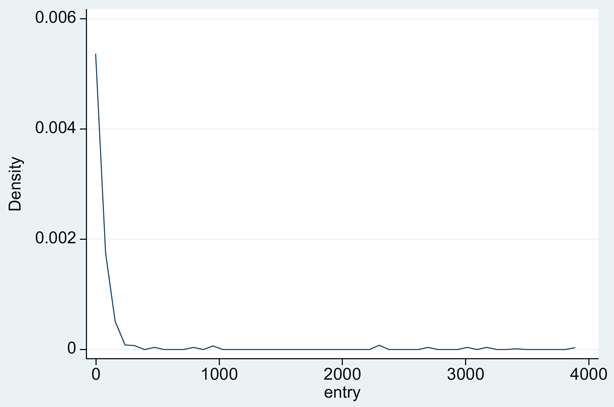

The level of analysis in our investigation is the individual municipality and the focal variable of interest is firm births (there are 286 municipalities in Sweden). To analyze how the regional characteristics described above affect firm births we use the Negative Binomial (NEGBIN) regression model. This model is commonly used for analyses of count data (see, e.g., Cameron & Trivedi, 1998) and is appropriate if the mean exceeds the variance in birth. The number of start-ups are count data and take on discrete values 0, 1, 2 …, up to a maximum of 3,174, which is the highest number of births in a municipality (Stockholm in 1999) during the time period of investigation. The average number of births is 32 but the median number is only 13, hence indicating highly skewed values as shown in Fig. 2. This substantiates the usage of count data analysis.

Fig. 2. Kernel Density Estimate of Knowledge-Intensive Start-Ups in Swedish Municipalities 1994–2002.

Independent Variables

Our analytical model is constructed in such a way so that it captures both supply- and demand-side factors, however with a specific emphasis on the demand side. Much of the existing literature on the link between entrepreneurship and characteristics of regions focuses on supply-side factors. We therefore control for supply-side effects that pertain to knowledge. The bulk of papers on differences in entrepreneurship across regions pay particular attention to the impact of concentrations of human capital- and knowledge-based investments in space.2 These often build on the “knowledge spillover theory of entrepreneurship” (Acs, Braunerhjelm, Audretsch, & Carlsson, 2009), focusing on the sources of knowledge that lead to the creation and development of new firms. The essence of the theory is that spillovers of knowledge and information are more frequent in regions with high densities of human capital and knowledge-based investments (Wright, Hmieleski, Siegel, & Ensley, 2007). Because of this, potential and existing entrepreneurs have higher probability of accessing knowledge that can constitute the basis for a new firm, such that accessibility to knowledge sources trigger start-ups. On the supply-side we include the overall knowledge-intensity of the workforce in the municipality. The variable – “% University educated” – is defined as the share of workers with a university education of at least three years. We also include a dummy for the presence of “University R&D in region” and another dummy for the presence of “Business R&D in a region.” The variables are in dummy format, denoting whether R&D among universities and companies in a region, respectively, exceeded that of the country's average. These three variables are included in view of the knowledge spillover theory of entrepreneurship (Acs et al., 2009) and controls for whether proximity to knowledge sources spurs knowledge-intensive entrepreneurship.

We also investigate sociological variables pertaining to demand-side factors known to affect entrepreneurship (Thornton, 1999). Specifically, we use the two variables suggested as imperative in the density dependency model of organizational ecology.

Firm density is the number of similar firms in existence during the time of founding in a focal municipality (and the squared term Firm density² to investigate nonlinearities).3 With an increasing number of firms in a new industry – such as IT consulting or Web design – knowledge and publication acceptation of this type of business spreads through media, business activities, and other types of knowledge flows. With increased knowledge this type of business becomes cognitively more accepted, hence alleviating investors and customers’ skepticism of the business and thus easing the ability of entrepreneurs to realize their idea in the socioeconomic sphere of daily life. The regional count of firms also captures legitimacy – it is easier to find role models on the other side of the street than in a far-away city (Bird & Wennberg, 2013) – however the regional count variable also is a strong indicator of competition, your neighboring firm might turn out to be your strongest competitor as well as a role model. The squared term is included to investigate nonlinearities, that is, when the negative hypothesized effect of competition on firm births overtakes the positive effect of legitimacy. These variables were taken from the RAMS database.

We include the variable “Political majority in region” as an indication of institutional conditions in the form of dominant political positions in each municipality (Bird & Wennberg, 2013). Our interest in this variable arrives from the socioeconomic models of firm emergence developed in organization theory (cf. Lounsbury, 2007). In such models, the birth and demise of organizations is not determined solely by economic forces but is portrayed as a social process shaped by a number of institutional actors such as governments, industrial associations, and trade unions that strive to advance their respective interests via persuasion and coercion (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). The validity of the variable denoting political control of a municipality hinges on the notion that local authorities wield coercive pressure that can hamper or facilitate the start-up activities of local firms, for example, indirectly or by influencing public administrators to avoid or delay application procedures and approval of operation in cases such applications are necessary. Obviously, this does not imply corruption but merely that sociocultural practice depends on the people set to administer such practices, and who dictates local parliamentary matters for administration and legislation. The interpretation of this variable demands caution since we cannot ascertain the exact theoretical mechanism by which the variable operates. Change in local governance might provide a source of sociopolitical legitimacy and/or simultaneously lead to some factual institutional reforms, and we cannot distinguish between the two. Similar to Giannetti and Simonov (2009) this variable takes the value −1 for socialistic majority, 1 for right-wing majority, and 0 for a mixed (coalition) majority, taken from Statistics Sweden’s public databases.

We investigate economic conditions that differ across municipalities and over time by four different variables. First, “GRP in region” controls for the general economic size of each municipality with a measure of Gross Regional Product (GRP). We also control for the “Median income in region” with a measure of income per capita in a focal municipality (approximates both supply of potential entrepreneurs and demand for their services). Finally, we introduce three dummy variables denoting regional characteristics of the local economy: “Metropolitan area” is a dummy variable that takes the value 1 for large urban areas and 0 otherwise. “Large public sector” takes the value 1 for municipalities that are dominated by public sector employment and 0 otherwise. “Large agricultural sector” takes the value 1 for municipalities that have a large agricultural sector (10% or more of GRP) or 0 otherwise. All these variables were taken from Statistics Sweden’s public databases.

Since the data constitutes a repeated cross-sectional time series panel, we include dummy variables for each year of analysis to control for unobservable effects pertaining to the economic cycle. All variables are time varying between 1994 and 2002, updated yearly for each municipality. The variables are summarized in Table 2. The maximum and minimum values, mean values, and their correlations are displayed in Appendix B. We estimate separate models for the births of high-tech manufacturing firms and the births of knowledge-intensive business services (KIBS) Firms. In both models, our variables for local economic conditions, ecological conditions, knowledge spillovers, and institutional conditions are entered hierarchically, with separate test of log-likelihood ratio to investigate the improvement in model fit when each block of variables are introduced (Appendix C).

Table 2. Explanatory Variables in the Empirical Analysis (Conditions across Municipalities).

| Types of Variable | Variable | Explanation |

| Economic conditions | GRP | Gross Regional Product |

| Economic conditions | Median income | Median income per capita in municipality |

| Economic conditions | Agriculture | Dummy for a large agriculture sector (35% employment) in municipality |

| Economic conditions | Public sector | Dummy for a large public sector (>35% employment) in municipality |

| Ecological conditions | Density | Number of firms (KIBS or high-tech manufacturing firms, respectively) in municipality |

| Ecological conditions | Density² | Squared number of firms (KIBS or high-tech manufacturing firms, respectively) in municipality |

| Knowledge spillovers | University educated | Proportion of university educated in the municipality |

| Knowledge spillovers | University R&D | Dummy for the presence of university R&D in the municipality (1 of positive R&D investments, 0 otherwise) |

| Knowledge spillovers | Business R&D | Dummy for the presence of business R&D in the municipality (1 of positive R&D investments, 0 otherwise) |

| Institutional conditions | Politics | Political majority in municipality (−1 = socialistic majority, 0 = mixed majority, 1 = right-wing majority) |