There has been a significant rise in the number of patents originating from academic environments. However, current conceptualizations of academic patents provide a largely homogenous approach to define this entrepreneurial form of technology transfer. In this study we develop a novel categorization framework that identifies three subsets of academic patents which are conceptually distinct from each other. By applying the categorization framework on a unique database of Swedish patents we furthermore find support for its usefulness in detecting underlying differences in technology, opportunity, and commercialization characteristics among the three subsets of academic patents.

INTRODUCTION

The active contribution of universities to economic development has become a cornerstone in modern higher education policy. This goes beyond the more traditional mandate of universities in providing academic education and basic research (Mowery, Nelson, Sampat, & Ziedonis, 2004) and emphasizes their potential role as engines for innovation and economic development via the transfer of scientific and technological knowledge to industry and broader society (e.g., Cohen, Nelson, & Walsh, 2002; Mansfield, 1998). Nowadays, universities are in this respect expected to serve as “innovation hubs” (e.g., Youtie & Shapira, 2008) in regional and national economies by supporting and promoting the commercialization of academic research conducted within their organizational boundaries (Rasmussen, Moen, & Gulbrandsen, 2006; Wigren-Kristoferson, Gabrielsson, & Kitagawa, 2011).

One widely recognized route for disseminating scientific and technological knowledge originating from universities is by means of academic patenting (Allen, Link, & Rosenbaum, 2007; Shane, 2004; Walsh & Huang, 2014). Academic patenting reflects a unique dimension of academic entrepreneurship since it represents and encapsulates scholarly inventive activity that results in intellectual property (IP) that can be commercially exploited (Allen et al., 2007; Shane, 2004). Academic patenting is also an interesting phenomenon for entrepreneurship scholars since patents provide legal protection from the appropriation of IP by competitors by granting an exclusive right to exploit the underlying technological opportunity on a market (Gans & Stern, 2003). In this respect, a patent provides signals that an academic invention has potential commercial value.

Since the 1980s there has been a significant rise in the number of patents originating from academic environments both in the United States and across Europe (e.g., Geuna & Nesta, 2006; Mowery, Nelson, Sampat, & Ziedonis, 2001; Trajtenberg, Henderson, & Jaffe, 1992; Wright, Clarysse, Mustar, & Lockett, 2007; Zucker & Darby, 2001). The growing interest among scholars in understanding both the determinants and spatial distribution of this trend stem from the underlying potential of academic patents as a technology transfer mechanism that aid entrepreneurial efforts to commercialize and diffuse academic research. Research on academic patenting has identified and distinguished between different kinds of patents as a basis for making theoretical and empirical studies. One main distinction is between university-invented and university-owned patents. The former coincide with the widely accepted definition of academic patents as “any patent signed at least by one academic inventor, while working at his or her university” (Lissoni, 2012, p. 198; see also similar ways of defining academic patents in Göktepe-Hultén, 2008; Ljungberg & McKelvey, 2012; Meyer, 2006). University-owned patents, on the other hand, are a subset of academic patents where universities who employ the inventors retain the IP created from research activity conducted in academic environments. Studies show for example that the relative weight of university-owned patents over academic patents depend largely on both intellectual property rights (IPR) regimes and historical levels of university autonomy embedded in a given country (Della Malva, Lissoni, & Llerena, 2013; Lissoni, Pezzoni, Poti, & Romagnosi, 2013) and these legal and institutional factors also play a significant role in explaining which channels are typically used for commercializing academic patents (e.g., Giuri, Munari, & Pasquini, 2013).

Another main distinction in the literature is between academic patents and corporate patents, where the latter represent IP originating from R&D efforts in private industry. The main issue in this stream of research has been to compare if academic and corporate patents have different or similar value distributions and also if they share common determinants of value (Czarnitzki, Hussinger, & Schneider, 2011; Sapsalis, van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie, & Navon, 2006). At least two generalities can be highlighted from past studies on this issue. First, as emphasized by Sapsalis et al. (2006, p. 1632) there are almost as many potential methodologies to assess the value of patents as the number of existing investigations. Second, studies seem on the aggregate to suggest that the value distribution of academic and corporate patents often is very close to each other (Czarnitzki et al., 2011; Henderson, Jaffe, & Trajtenberg, 1998; Sapsalis et al., 2006). This latter issue may suggest that patent value is driven by things other than inventorship or ownership, but it may also signal that the current way of distinguishing between different kinds of patents are too coarse to detect meaningful features and underlying characteristics.

While past research on academic patents to a large extent has been driven by methodological concerns related to the exploration and assessment of appropriate indicators and building up comprehensive and reliable datasets (Lissoni, 2012), in this study we are interested in understanding academic patenting in the broader frame of academic entrepreneurship. A widely diffused approach in the literature is the highly systemic approach that is taken into account for understanding the dynamic interactions between scholarly research and related technology transfer initiatives, both within the university system itself as well as in collaboration with industry (Kirby, 2006; Rothaermel, Agung, & Jiang, 2007). For example, in their comprehensive and detailed literature review, Rothaermel et al. (2007, pp. 706–708) conceptualize the core of the overall university innovation system as the advancement and diffusion of university-generated technology. This core is furthermore facilitated through technology transfer offices (TTOs) and other intermediaries such as incubators and science parks. However, these intermediaries expand academic entrepreneurship to also include agents and activities outside the local university system and where universities become embedded in a larger environmental context which encompass university–industry ties and other supporting networks of innovation (Balconi, Breschi, & Lissoni, 2004; Beaudry & Kananian, 2013). In this respect, universities assume an expanded boundary-spanning role where they are expected to meditate among academic, industrial, and public spheres in the broader innovation system surrounding these entities (Rothaermel et al., 2007; Youtie & Shapira, 2008).

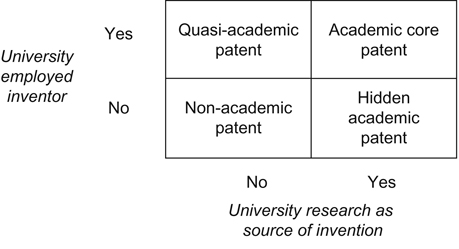

In this study we follow the systemic approach advocated by Rothaermel et al. (2007). Academic patents as an entrepreneurial form of university technology transfer are in this respect often conceptualized and understood in terms of the professional affiliation of its inventors (Lissoni, 2012). However, when framed as embedded in a larger university innovation system (Rothaermel et al., 2007) academic patents can also be conceptualized and understood in terms of IP originating from academic environments (Shane, 2004), thus creating dual entries for understanding the phenomenon. Interestingly, this duality in understanding academic patents target a fundamental issue in contemporary research on academic patents; namely that of how to define and demarcate the phenomenon. In this respect, based on our argumentation above we argue in this study for the need to open up and develop the conceptualization of academic patents based on the professional affiliation of the inventor (Lissoni, 2012; Ljungberg & McKelvey, 2012) by also including whether the source of the IP underlying the invention originated from academic research (Shane, 2004).

Against this backdrop, the aim of this study is to develop and refine our understanding of academic patents by presenting and testing a novel categorization framework to better understand the complex and multidimensional nature of this phenomenon. While past research on academic patents undoubtedly has contributed to the development of a rich and highly potent body of scholarly knowledge, we believe that defining academic patents based only on the professional affiliation of the inventor(s) provide an overly simplified and largely homogeneous view of this entrepreneurial form of university technology transfer that potentially hide underlying differences in opportunity and commercialization characteristics. In this scholarly effort, we thus challenge the traditional way of defining academic patents by identifying three different and conceptually distinct categories of academic patents:

- Academics employed by a university who patent inventions originating from university research

- Academics employed by a university but who patent inventions originating from sources outside the university

- Individuals that are not employed by a university but who patent inventions originating from university research

The central hypothesis we put forward in this study is that a more elaborated definition and categorization of academic patents can open up for identifying and distinguishing potential differences in technology, opportunity and commercialization characteristics. By providing such a framework, the study has great potential to contribute to current literature and research on academic entrepreneurship in several ways. First and foremost, our framework builds on and integrates findings from the broader literature on academic entrepreneurship by recognizing that university-employed academics can be engaged in a wide range of enterprising activities outside their own research (Klofsten & Jones-Evans, 2000; Wigren-Kristoferson, Gabrielsson, & Kitagawa, 2011), which may then serve as a viable source of academic inventions. The framework also recognizes that academic patents may be based on IP originating from academic research but where the inventor(s) are not formally employed by a university at the time when the patent is applied for (Lindholm Dahlstrand, 1999). Hence, although university-employed academics who patent inventions may base this more or less directly linked to their own academic research there is a potential risk that definitions of academic patents that look only on the affiliation of the inventor may contain a proportion of not-so-relevant patents (a type I error) while also missing other patents that would be potentially relevant to include and assess (a type II error).

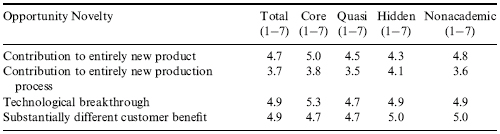

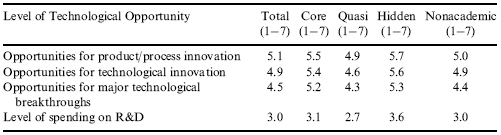

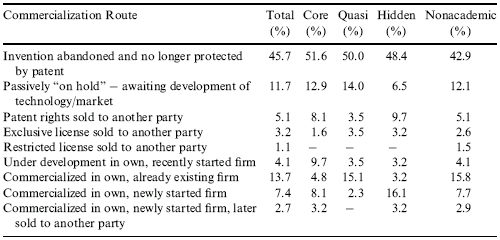

Second, our framework for categorizing different kinds of academic patents has also potential to generate a more fine-grained understanding of academic patents with respect to their features and underlying characteristics. Based on a unique handcrafted database with detailed information about patents granted to private individuals in Sweden between 1996 and 2005, we analyze whether the resulting categories of academic patents perform with respect to parameters such as technological fields (Ernst, 2003), novelty (Abernathy & Clark, 1985), level of technological opportunity which underlie the patented invention (Zahra, 1996) as well as their routes of commercialization (Giuri et al., 2013; Svensson, 2012).

Third, we also believe that the categorization framework that we develop in this study can be a useful device for TTO managers and other actors who operate in the university innovation system with the assigned task of promoting and supporting technology transfer. Our approach provides them with a theoretical foundation for distinguishing, segmenting, and targeting different groups of academic patents. Much in line with the comment by Gartner (1985) that the process of creating a business is not “a well-worn route marched along again and again by identical entrepreneurs” (p. 697), we analogously emphasize that there is little practical value in conceptualizing academic patents as a homogenous group of inventions. Following this line of reasoning we thus suggest that different kinds of academic patents can be conceptually distinguished from each other based on two basic dimensions; one based on whether the patent is signed at least by one academic inventor (Lissoni, 2012), and the other based on whether the IP underlying the patented invention originated from an academic environment (Shane, 2004). Thereby, our categorization framework enables the development of more tailored and customized efforts to promote technology transfer initiatives, which also support the current move toward embracing an economic development mandate in contemporary higher education policy.

REFERENCES

Abernathy, W. J., & Clark, K. B. (1985). Innovation: Mapping the winds of creative destruction. Research Policy, 14(1), 3–22.

Aghion, P., & Howitt, P. (1992). A model of growth through creative destruction. Econometrica, 60(2), 323–352.

Allan, S. (2000). Using the international patent classification in an online environment. World Patent Information, 22, 291–300.

Allen, S. D., Link, A. N., & Rosenbaum, D. T. (2007). Entrepreneurship and human capital: Evidence of patenting activity from the academic sector. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 31(6), 1042–2587.

Angelmar, R. (1985). Market structure and research intensity in high-technological opportunity industries. Journal of Industrial Economics, 34, 69–79.

Audretsch, D. (1995). Innovation and industry evolution. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Balconi, M., Breschi, S., & Lissoni, F. (2004). Networks of inventors and the location of academic research: An exploration of Italian data. Research Policy, 33(1), 127–145.

Beaudry, C., & Kananian, R. (2013). Follow the (industry) money: The impact of science networks and industry-to-university contracts on academic patenting in nanotechnology and biotechnology. Industry and Innovation, 20(3), 241–260.

Bray, M. J., & Lee, J. N. (2000). University revenues from technology transfer – Licensing fees vs. equity positions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(5), 385–392.

Brockhoff, K. (1991). Competitor technology intelligence in German companies. Industrial Market Management, 20, 91–98.

Christensen, C. M. (1997). The innovator’s dilemma: When new technologies cause great firms to fail. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Clark, B.-R. (1998). Creating entrepreneurial universities: Organizational pathways of transformation. Oxford: Elsevier Science.

Cohen, W., Nelson, R. R., & Walsh, J. (2002). Links and impacts: The influence of public research on industrial R&D. Management Science, 48, 1–23.

Cozzi, G., & Galli, S. (2014). Sequential R&D and blocking patents in the dynamics of growth. Journal of Economic Growth, 19, 183–219.

Crespi, G., Geuna, A., & Nesta, L. (2007). The mobility of university inventors in Europe. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 32(3), 195–215.

Czarnitzki, D., Hussinger, K., & Schneider, C. (2011). Commercializing academic research: The quality of faculty patenting. Industrial and Corporate Change, 20(5), 1403–1437.

Della Malva, A., Lissoni, F., & Llerena, P. (2013). Institutional change and academic patenting: French universities and the innovation act of 1999. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 23(1), 211–239.

Edquist, C., & Hommen, L. (2008). Small country innovation systems: Globalization, change and policy in Asia and Europe. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Ernst, H. (2003). Patent information for strategic technology management. World Patent Information, 25(3), 233–242.

Fagerberg, J., Mowery, D., & Nelson, R. (2004). The Oxford handbook of innovation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Feller, I., Ailes, C. P., & Roessner, J. D. (2002). Impacts of research universities on technological innovation in industry: Evidence from engineering research centers. Research Policy, 31(3), 457–474.

Freeman, C., & Louca, F. (2001). As time goes by. from the industrial revolutions to the information revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fung, M. K. (2004). Technological opportunity and productivity of R&D activities. Journal of Productivity Analysis, 21(2), 167–181.

Gabrielsson, J., Politis, D., & Lindholm Dahlstrand, Å. (2013). Patents and entrepreneurship: The impact of opportunity, motivation and ability. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 19(2), 142–166.

Gans, J. S., & Stern, S. (2003). The product market and the market for “ideas”: Commercialization strategies for technology entrepreneurs. Research Policy, 32(2), 333–350.

Gartner, W. B. (1985). A conceptual framework for describing the phenomenon of new venture creation. Academy of Management Review, 10, 696–706.

Geroski, P. (1990). Innovation, technological opportunity, and market structure. Oxford Economic Papers, 42, 586–602.

Geuna, A., & Nesta, L. J. J. (2006). University patenting and its effects on academic research: The emerging European evidence. Research Policy, 35, 790–807.

Giuri, P., Munari, F., & Pasquini, M. (2013). What determines university patent commercialization: Empirical evidence on the role of IPR ownership. Industry and Innovation, 20(5), 488–502.

Granstrand, O. (1999). The economics and management of intellectual property: Towards intellectual capital. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Granstrand, O. (2006). Intellectual property rights for governance in and of innovation systems. In and Anderson, B. (Ed.), Intellectual property rights: Innovation, governance and the institutional environment. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Griliches, Z. (1990). Patent statistics as economic indicators: A survey. Journal of Economic Literature, 28, 1661–1707.

Göktepe-Hultén, D. (2008). Academic inventors and research groups: Entrepreneurial cultures at universities. Science and Public Policy, 35(9), 657–667.

Henderson, R., Jaffe, A., & Trajtenberg, M. (1998). Universities as a source of commercial technology: A detailed analysis of university patenting, 1965–1988. Review of Economics and Statistics, 80(1), 119–127.

Jacobsson, S., Lindholm Dahlstrand, Å., & Elg, L. (2013). Is the commercialization of European academic R&D weak? A critical assessment of a dominant belief and associated policy responses. Research Policy, 42(4), 874–885.

Jaffe, A. (2000). The U.S. patent system in transition: Policy innovation and the innovation process. Research Policy, 29, 531–557.

Jaffe, A. B. (1986). Technological opportunity and spillovers of R&D: Evidence from firms’ patents, profits and market value. American Economic Review, 76(5), 984–1001.

Jonassen, D. H. (1992). What are cognitive tools? Cognitive Tools for Learning, 81, 1–6.

Kirby, D. A. (2006). Creating entrepreneurial universities in the UK: Applying entrepreneurship theory to practice. Journal of Technology Transfer, 31(5), 599–603.

Klofsten, M., & Jones-Evans, D. (2000). Comparing academic entrepreneurship in Europe – The case of Sweden and Ireland. Small Business Economics, 14(4), 299–309.

Lindholm Dahlstrand, Å. (1999). Technology-based SMEs in the Göteborg region: Their origin and interaction with universities and large firms. Regional Studies, 33(4), 379–389.

Lindholm Dahlstrand, Å., & Berggren, E. (2010). Linking innovation and entrepreneurship in higher education: A study of Swedish schools of entrepreneurship. In and R. Oakey, A. Groen, G. Cook, & P. Van Der Sijde (Eds.), New technology-based firms in the new millennium (pp. 35–50). Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Lissoni, F. (2012). Academic patenting in Europe: An overview of recent research and new perspectives. World Patent Information, 34, 197–205.

Lissoni, F., Llerena, P., McKelvey, M., & Sanditov, B. (2008). Academic patenting in Europe: New evidence from the KEINS database. Research Evaluation, 17, 87–102.

Lissoni, F., Pezzoni, M., Poti, B., & Romagnosi, S. (2013). University autonomy, IP legislation and academic patenting: Italy, 1996–2007. Industry and Innovation, 20(5), 399–421.

Ljungberg, D., & McKelvey, M. (2012). What characterizes firms’ academic patents? Academic involvement in industrial inventions in Sweden. Industry and Innovation, 19(7), 585–606.

Mansfield, E. (1998). Academic research and industrial innovation: An update of empirical findings. Research Policy, 26, 773–776.

Mansfield, E., & Lee, J. L. (1996). The modern university: Contributor to industrial innovation and recipient of industrial R&D support. Research Policy, 25, 1047–1058.

Meyer, M. (2003). Academic patents as an indicator of useful research? A new approach to measure academic inventiveness. Research Evaluation, 12(1), 7–27.

Meyer, M. (2006). Academic inventiveness and entrepreneurship: On the importance of start-up companies in commercializing academic patents. Journal of Technology Transfer, 31(4), 501–510.

Mowery, D. C., Nelson, R. R., Sampat, B., & Ziedonis, A. A. (2001). The growth of patenting and licensing by U.S. universities: An assessment of the effects of the Bayh–Dole Act of 1980. Research Policy, 30(1), 99–119.

Mowery, D. C., Nelson, R. R., Sampat, B. N., & Ziedonis, A. A. (2004). “Ivory Tower” and industrial innovation: University–industry technology transfer before and after the Bayh–Dole Act. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Rasmussen, E., Moen, Ø., & Gulbrandsen, M. (2006). Initiatives to promote commercialization of university knowledge. Technovation, 26(4), 518–533.

Rhodes, G., & Slaughter, S. (2004). Academic capitalism in the new economy: Challenges and choices. American Academic, 1(1), 37–59.

Rothaermel, F. T., Agung, S. D., & Jiang, L. (2007). University entrepreneurship: A taxonomy of the literature. Industrial and Corporate Change, 16(4), 691–791.

Sampat, B. N. (2006). Patenting and US academic research in the 20th century: The world before and after Bayh–Dole. Research Policy, 35, 772–789.

Sapsalis, E., & van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie, B. (2007). The institutional sources of knowledge and the value of academic patents. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 16(2), 139–157.

Sapsalis, E., van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie, B., & Navon, R. (2006). Academic versus industry patenting: An in-depth analysis of what determines patent value. Research Policy, 35(10), 1631–1645.

Schumpeter, J. (1939). Business cycles: A theoretical, historical, and statistical analysis of the capitalist process. (Vol. 2). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Schumpeter, J. A. (1934). The theory of economic development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Schumpeter, J. A. (1942). Capitalism, socialism and democracy. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Schwartz, E. S. (2004). Patents and R&D as real options. Economic Notes, 33(1), 23–54.

Serrano, C. J. (2008). The dynamics of the transfer and renewal of patents. NBER Working Paper No. 13938, pp. 1–26. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Shane, S. (2004). Academic entrepreneurship: University spinoffs and wealth creation. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Shane, S., & Stuart, T. (2002). Organisational endowments and the performance of university spin-offs. Management Science, 48(1), 122–137.

Smith, D. (2005). Exploring innovation. London: McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

Svensson, R. (2012). Commercialization, renewal, and quality of patents. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 21(2), 175–201.

Thursby, J. C., & Thursby, M. C. (2002). Who is selling the ivory tower? The sources of growth in university licensing. Management Science, 48, 90–104.

Trajtenberg, M., Henderson, R., & Jaffe, A. B. (1992). University versus corporate patents: A window on the basicness of inventions. CEPR Working Paper No. 372, Stanford University, Stanford.

van Zeebroeck, N., van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie, B., & Guellec, D. (2008). Patents and academic research: A state of the art. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 9(2), 246–263.

Walsh, J. P., & Huang, H. (2014). Local context, academic entrepreneurship and open science: Publication secrecy and commercial activity among Japanese and US scientists. Research Policy, 43(2), 245–260.

Wigren-Kristoferson, C., Gabrielsson, J., & Kitagawa, F. (2011). Mind the gap and bridge the gap: Research excellence and diffusion of academic knowledge in Sweden. Science and Public Policy, 38(6), 481–492.

Wright, M., Clarysse, B., Mustar, P., & Lockett, A. (2007). Academic entrepreneurship in Europe. Cheltenham, UK: Edgar Elgar.

Youtie, J., & Shapira, P. (2008). Building an innovation hub: A case study of the transformation of university roles in regional technological and economic development. Research Policy, 37(8), 1188–1204.

Zahra, S. A. (1996). Governance, ownership and corporate entrepreneurship: The moderating impact of industry technological opportunities. Academy of Management Journal, 39(6), 1713–1735.

Zucker, L. G., & Darby, M. R. (2001). Capturing technological opportunity via Japan’s star scientists: Evidence from Japanese firms’ biotech patents and products. Journal of Technology Transfer, 26(1–2), 37–58.