The Sphinx, a picturesque natural feature of Girraween National Park

PARK INFORMATION

NPRSR 13 7468

SIZE

11 800 ha

LOCATION

260 km south-west of Brisbane; 35 km south of Stanthorpe; 39 km north of Tenterfield, NSW

PERMITS

Camping permit and fees apply; bookings essential

ACCESS

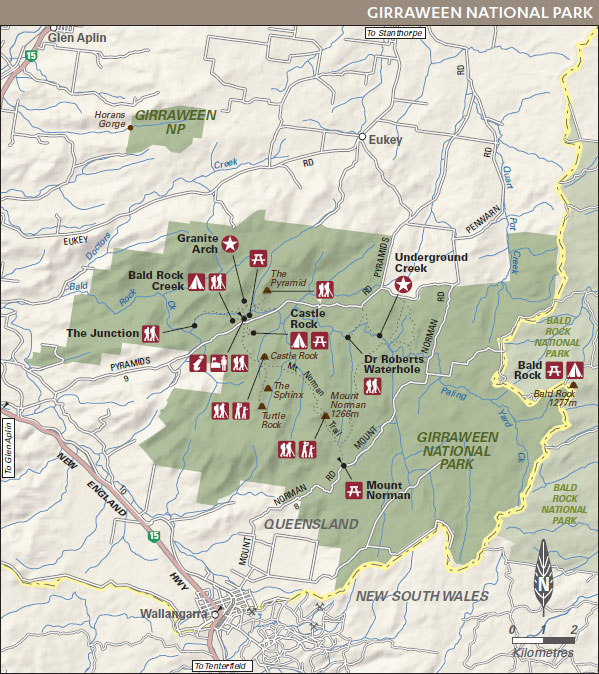

From Stanthorpe and Tenterfield via New England Hwy and Pyramids Rd; an alternative route from Stanthorpe via Eukey and Storm King Dam contains gravel sections and is 4WD only in wet weather

BEST SEASON

Late July to January

VISITOR INFORMATION

Stanthorpe (07) 4681 2057 | Tenterfield (02) 6736 1082 | www.granitebeltwinecountry.com.au

MUST SEE, MUST DO

MARVEL at the park's famous wildflowers in bloom

CLIMB The Pyramid and take in a breathtaking view including geological oddity Balancing Rock

REVEL in the cool climate, which has more in common with the New England plateau than the rest of the Sunshine State

Just south of Stanthorpe, one of Queensland's premier tourist destinations, Girraween National Park is easy to access, but don't let that fool you – this park contains an untamed landscape of arresting and stark granite formations. The best time to visit is during spring, when wildflowers offer riotous bursts of colour between the boulders while in summer orchids and flannel flowers appear.

A look at the past

The first European to arrive in the area now marked out as Girraween National Park was the renowned explorer and botanist Allan Cunningham, who passed through the region in June 1827. He soon turned back and skirted around the area, as the landscape proved difficult to traverse – and the area's now-famous wildflowers, which might have captivated Cunningham, were not yet in bloom. Owing to the inhospitable lay of the land, Girraween remained untouched as large-scale settlement of the nearby Granite Belt and Darling Downs areas occurred in the early 1840s. The area was occupied in 1843 by the squatter Robert Ramsay Mackenzie, who soon went bankrupt; his manager, Henry Hayter Nicol, established the station known as Nicol's Run in 1844.

Farmers arrived in 1898 after Nicol's Run was opened for selection. Enterprising settlers tried their hand at farming sheep, raising dairy cattle and growing vegetables and fruit, but the land proved unsuitable, and farms changed hands frequently as would-be entrepreneurs walked or were driven away by the difficult conditions. Several of these farm buildings (including some interesting stone buildings erected in the 1970s) remain today, some of them serving as workshops and barracks for QPWS staff.

Girraween National Park began as two separate national parks, Bald Rock Creek and Castle Rock, declared in 1930 and 1932 respectively. The land between these parks was acquired in 1966, and the area rechristened Girraween after an Indigenous word meaning 'place where flowers grow'. The park steadily expanded through government land acquisitions, reaching its current size of 11 800 hectares in 1980.

Aboriginal culture

Little is known about the region's traditional owners, the Bundjalung, Gidabal, Jukambal, Kambuwal, Kwiambal and Ngarabal people. (The name 'Girraween' is not derived from any of these groups' languages.) The large number of Indigenous groups recorded in the area suggests that Girraween may have been a meeting place. Evidence of these groups' way of life remains in the form of marked trees, camping places, tools and other artefacts.

Natural features

Girraween is known for its dramatic granite outcrops, the product of tectonic activity that took place between 200 and 400 million years ago. These outcrops were formed as columns of magma trapped inside sedimentary rock; as the softer sedimentary rock eroded, the harder granite columns remained as the stunning outcrops that draw visitors to the park today. The more picturesque outcrops, such as Turtle Rock and the Sphinx, are well served by walking tracks.

Native plants

As the name suggests, Girraween truly is a place where flowers grow. From the end of July, the park erupts with colour as native wildflowers blossom – golden acacias liven the canopy above, while yellow, purple and red pea flowers cover the ground below. Creamy white heath bells appear in September, and the riotous display of flowers continues well into summer as bottlebrushes, flannel flowers and more acacias bloom.

Wildlife

The flowers of Girraween don't just attract human visitors – the abundant blossoms bring a diversity of insect life, and the insects' natural predators follow. The park is home to over 150 different bird species including satin bowerbirds, red wattlebirds, crimson rosellas, superb lyrebirds, and the threatened turquoise parrot. The granite outcrops – perfect for sunning – support a wealth of reptile life, including the Cunningham's skink, eastern water dragons and jacky lizards. The red-bellied black snake is the most common snake in the park; the aggressive and highly venomous eastern brown snake has also been found, so visitors should keep a wary eye out.

Camping and accommodation

Campers are well served at Girraween, but come prepared – the park's elevation (an average of 900 metres above sea level) means that even summer nights can be chilly, while frosts are not uncommon in winter. Fortunately, both of the park's camping areas contain hot showers and allow wood fires in designated fireplaces. More adventurous souls can camp at one of six designated bush camping areas, but bring a warm sleeping bag – open fires are prohibited here. Campsites must be booked and permit fees paid for in advance. Those looking for creature comforts should head to nearby Stanthorpe, which offers a range of B&B accommodation near to local wineries.

Things to do

The park's main attraction is its distinctive granite outcrops, around which many walking trails thread. Some facilities in the Castle Rock camping area and Bald Rock Creek day-use areas have wheelchair access, but there are no wheelchair-friendly nature trails, and many of the walks are physically challenging.

BUSHWALKING There are many walking tracks in the park, ranging from short strolls to long and difficult treks. The shortest, Wyberba Walk (200 metres, 15 minutes, easy), meanders alongside Bald Rock Creek and offers views of The Pyramid rock formation, as well as excellent wildflowers in spring. The Granite Arch Track (1.4 km, 35 minutes, easy) is popular with daytrippers and those pressed for time. A circuit track, it winds past a naturally formed stone arch. Those looking for more challenging walks will relish the Castle Rock (5.2 km, 2 hours, difficult) and The Pyramid (3.4 km, 2 hours, difficult) tracks, each of which scales granite formations to reveal breathtaking views. Both of these tracks involve rock scrambles, and neither provides ropes or other climbing aids. The summits have steep cliffs, so caution is required.

ROCK-CLIMBING Groups of experienced rock climbers can access some of the granite formations that the park's bushwalking trails do not service. Climbers can crest the summit of Mount Norman's monolith via the nearby walking trail. More experienced climbers can attempt the difficult climb up the Second Pyramid – there is no trail to the base of the formation, and climbs should only be attempted after consultation with a park ranger.

WILDIFE-WATCHING The park's inhospitable character has acted as a natural protection for the area's rich and diverse wildlife. Birdwatchers in particular will appreciate the large array of bird species that come out in spring. The park arranges guided tours and talks during holiday periods to inform visitors about the park's wildlife.