17

“YOU CAN COME WITH ME; OR YOU CAN STAY. BUT WHICHEVER YOU CHOOSE, I’m going.” Despite frustrations and confusions Lucy had never quarreled with Alex: but she was close now. She was very emotional about this decision. It had taken her weeks to get permission, and everything was in place. She was back at work part-time and had to juggle her own schedule now. She had booked a room to stay from Friday to Sunday, and was ready intellectually for the experience. More than that, something drove her to the necessity of going. It had to be now.

Alex was distraught. He’d worked a month straight every hour he wasn’t with students or at the hospital to get his thesis in—which in itself had been a mountain to climb—but what had driven him was the desire to free up some time in the future as a by-product. Lucy had mentioned a fortnight before that she was going to Chartres for the spring equinox. She was particular as to the time, and had arranged with the cathedral to walk the labyrinth before the season officially started, after closing hours. He knew she’d gone to a lot of trouble and used her television credentials to help make it happen. Will’s postcards had intrigued her. She wanted to see whatever it was that Alex’s brother had seen at first hand. She wanted to dance the ancient Rite of Spring at the proper moment.

While he was surprised it meant so much to her, Alex was in fact quite curious himself and concerned about her going alone. So he told her simply at lunch a few days prior: “I’d like to come with you.” Delight and relief flooded her senses. She hadn’t expected this.

They’d grown closer since her birthday, considering the usual frustrations of time. “It’s not advisable,” she had sighed to Grace, “to start feeling anything for a man who is divorced, with a son I still haven’t met, a full-time job, and a research degree to complete.” Secretly, though, she had a deeper worry, questioning for weeks whether Alex’s failure to get intimately involved with her had anything to do with the uncertainty of her health. She knew he’d lost his mother and brother in less than a year. He didn’t talk about it, and never let his mask slip, but she understood without explanation that the pain was still raw. Could she blame him for holding back on starting a full relationship that might end at any time? Heart transplants were achieving better and better results for survival beyond the first crucial year, but there were certainly no guarantees. But now she’d hoped she might be able to put her doubts to rest. She would find out what there was between them and settle the uncertainties, and she’d been able to think of hardly anything else for weeks now.

For his own part, Alex had managed to clear the whole of Friday as well as the weekend. He was looking forward to walking the maze with her in the evening and then finally being allowed to spend some time alone with her, when suddenly their progress was blocked in an unprecedented form. It was impossible to digest. If she’d been listening, the distress in his voice would have told her half of what she needed to know; but Lucy felt absurdly thwarted. She felt fate was against them, and convinced herself that it was not to be. It was a lesson not to give away your heart. Moved only by her own sense of rejection—the ebb and flow of unexpected pleasure followed by intense disappointment—she was deaf to the emotions Alex’s tone communicated. All she processed was the unwelcome news that his ex-wife had asked him to have Max for the weekend because of a family crisis on her side—something to do with a mother in hospital.

“It’s fine, Alex,” Lucy told him—and it was transparent to him that it wasn’t. She said she accepted that he had duties. But she would go alone. She hadn’t asked him to come in the first place. She was just polite enough to force out “good night,” and then she hung up in tears. She’d completely forgotten how that felt.

Alex put the phone down and snapped the pencil in his hands. He’d never let Anna down in a genuine emergency. And he’d never let Max down. There was no Will to help him out. Was there another solution or must he let Lucy down? She couldn’t change the date, and he couldn’t change the problem. Impasse.

EARLY ON FRIDAY, GRACE AND SIMON DROVE HER TO WATERLOO, AND Simon lifted her bag out of his Land Rover. “Are you sure you don’t want company? We could always ring in sick.”

Lucy gave Simon a big hug. “You’re wonderful. No, I think I want to do this alone. I need some time alone, actually. I find I have a lot to think about.”

“Do you know what it is you’re looking for?”

“I’ve no idea. If I find out I’ll send you a postcard!” She managed a laugh.

“Make sure it’s one of an angel!” Simon added with a wry smile.

The two of them had sat on the floor at Alex’s London flat on the previous two Sunday afternoons, with gloved hands, surrounded by the texts of the astonishing documents Lucy had unwrapped in the silver-wrought chest at Longparish. A strange birthday present, Alex had called it: eighteen leaves of ancient vellum, which had kept them from their dinner on the snowing night of her birthday; each one of those sheets crisscrossed with riddles and clues to some other, equally obscure find. The first of them was the one Will had a copy of—some kind of original of the text that had come to him, bequeathed with the key. There was now, as she had thought before, a quire of them, inscribed front and back. The whole legacy had been buried under the giant mulberry in Alex’s family garden, exactly as she had said, with only a golden Elizabethan “angel”—a coin of considerable value—buried with them as a bedfellow. Henry had suggested it was Dee’s way of paying the ferryman—an angel that assured the box’s survival down the passage of centuries. It had been there, clearly, for four hundred years—the coin having been dated from its mint mark of “0” to around 1600. All of the paperwork was still legible, fairly uncorrupted, spotted with only the smallest amount of mildew—not even particularly deep in the ground, Alex had retold them as they sat mesmerized by the lines of verse and the intersecting patterns on the reverse. No one had known anything about them being there, it seemed. Alex told them both, with a healthy dose of skepticism, that the tree was alleged to have been a cutting from the great mulberry of Shakespeare’s—which itself had been a gift from King James when he was obsessed with seeding the silk industry. He’d imported the wrong genus of mulberry, and Morus nigra, the black tree, refused to support the silk-worms. But the ancient tree was wonderful, and Alex remembered coming back into the house with stained hands and mouth throughout his childhood as the first flush of berries every season enticed two little boys to gorge themselves. He could still taste them. Why it was the mulberry—why Lucy had made the leap of understanding—was a riddle itself. All she had been able to say, from that day to this, was that the portrait had told her.

She blocked the thoughts of Alex and his space now as she kissed her friend.

“Look after yourself, babe.” Simon handed Lucy through the barrier and put an arm around Grace’s waist. She stepped onto Eurostar and sank into her seat in sadness. This was no longer the trip she’d been anticipating for the last few days, and she wished the phone hadn’t rung last night. But it was a trip she was determined to make, and she hung on to the compelling feeling that she would satisfy some unspecified desire and deal with the problem of Dr. Alexander Stafford later. The Three Fates were in league against her and she must, sensibly, resign her hopes with him. But some other very different destiny was out there for her; and she would find it.

ALEX PICKED MAX UP FROM CRABTREE LANE EARLY THAT MORNING TO GIVE a distracted Anna a head start north to her family where her mother, he learned more fully, was about to undergo exploratory surgery. He sounded upbeat for her sake and gave her some good advice and a few reassurances. He decided to take Max out for breakfast as a treat, then dropped him at school; but when he drove back home with the groceries, weariness crept over him. This was his first day off for weeks, and he was at a loss how to fill it. He’d mark some of his students’ papers. He’d go for a walk along the river. He’d read for a while. All he wanted to do was call Lucy. To say what? She wasn’t happy with him. Her rational brain understood his dilemma. Her emotional being was undermined. He’d let things cool down a little, he decided. Then he picked up his phone and dialed her cell.

“Yes?” Her voice unreadable. She must have seen his number ID.

“Lucy.”

“Alex?”

Since she was steeling herself to cope with disappointment her voice was crisp. He couldn’t phrase anything. He wanted to remind her to take her medication with attention to French time, to eat something regularly, to stay warm—which was really an excuse to communicate how strongly he wished he were with her. But she’d resent him overcosseting her—a poor substitute for his presence. He felt wrong-footed, and said simply, “Good luck tonight.” She said nothing; and he spoke again in no more than a whisper. “‘Tread softly…’” He had no idea if she knew Yeats’s poem, but it was all he could say to her.

He replaced the receiver, and picked up the postcard of the Chartres labyrinth Will had sent to Max, which he’d hung on to. “Well,” he whispered, “you’d never get yourself into a problem quite like this one, would you? What to do?” He put the postcard on his dining table and took out the baffling bundle of documents that had come to light after Lucy’s bizarre revelation. He had a day off. Perhaps it was time for him to take a proper look at them.

IT WAS SIX-THIRTY P.M. THE VERGER MET HER UNDER THE ARCH OF THE TRANSEPT. She’d never been to Chartres, never been so affected by a religious space. She’d spent the last hour of the day letting the light of the stained glass tickle her face, her eyes fixed on the rose windows. She’d sat and just looked up. It was awe-inspiring, and she couldn’t quite take it in. She thought about the way the light worked: it was a high space, and the light drew your eyes up to it. In England, cathedrals were longer and lower, and she’d heard Alex say that was perfect for the lingering light of English twilight. French sunshine was more brilliant perhaps, and the power of the light to penetrate the gloom was exceptional, forcing your head up all the time. She’d lit a candle for her mother, wherever she was; one for her father; and two others, for two people she’d never met. She had tried to leave her thoughts of Alex and his family out of today, but she found she couldn’t. She was affected by what he said on the phone—albeit in the briefest words. She wished he were here. A man had been watching her—an unpleasant reality of being a young woman traveling alone. She’d forgotten how irritating it was—in fact, how disturbing it could be—and she wished she had Alex’s arm to hold. Now, in any case, she was here with the verger and just three other people who were sharing this private tour. They would each walk the sacred path, he told her. The seating had been moved, and candles were lit along the great looping coils. The setting was transcendent.

A guide with the verger began explaining in English. “In the twelfth century certain cathedrals were decreed pilgrimage cathedrals to relieve the numbers of people making journeys to the unstable Holy Land at the time of the Crusades. Many of these had labyrinths added, which became known as ‘the Road to Jerusalem.’ Originally they were walked at Easter, just as the classical labyrinths had been a dance of spring to celebrate returning vegetation. The experience of walking, however, was meditative, calming, focusing. Many people find it brings them nearer to heaven, ready to comprehend the will of God. For the minutes that you walk it, you are outside of time: your concerns are inward and spiritual, rather than material and temporal.”

The stream of information bubbled along, but Lucy’s thoughts spiraled wildly. The candles made a liquid pool, bent backward and forward, cast shadows through the long nave. She wanted the others to go first: she had to walk last, without anyone watching her. Her mind skipped, and she gave herself up to the extraordinary play of light and shadow. She wanted to be outside of time.

And then it was her turn—more than half an hour had raced away, and her feet were heading into the labyrinth with a will of their own.

IT WAS SIX IN THE EVENING. MAX SETTLED TO WATCH SOME TELEVISION after he’d eaten an unusually early dinner, and Alex stretched out near him on the sofa with a glass of Bordeaux. He had sorted the papers carefully into sections and picked up the first sheet again. He thought of Lucy in Chartres with Will’s working copy of this same text; it made him feel close to her, and ache to be there. Our two souls, therefore… He felt that Donne understood something precisely relevant for them. Lucy and he were divided in space, but not in thought at the moment. He would describe their two souls as one for now—they were outside of time. It must be seven in France, he thought. He took up Will’s postcard of the labyrinth and looked at it, then he read some more of the text of the old document. I am what I am, and what I am is what I am…I have a will to be what I am. Alex played with the words, all weighted monosyllables, over and again. He sat up after a minute and wrote on a notepad: Will, I am. William.

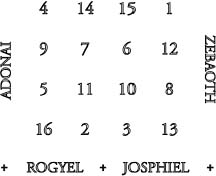

He turned over Will’s postcard, looking at the message he’d written to Max, and he started working on the geometrical pattern Will had drawn. Max asked a question, and Alex said “yes” without really computing what he’d said. He sat up again and stared at the card: and then the text. Bottom left is a square. Bottom right is a square. He traced the patterns Will had made. He had quite literally figured this, then: the five intersecting squares were a visual representation of the words. It reminded Alex of the mathematical squares they studied at Cambridge: magic number squares. Usually the whole sequence added up to a number, but the interior sections of the square added up to a common number too.

I am halfway through the orbit. He swallowed some wine. There was a magic square on one of the pages of vellum. What was half the number of the whole? he wondered.

THEY TOLD LUCY TO TREAD CAREFULLY AMONG THE LIGHTED CANDLES. Lucy nodded and tiptoed into the first snaking coil of the path. “‘Tread softly…’” she heard Alex’s voice, and she thought of what Yeats said about treading on dreams. On my dreams too, she realized, and the words of the poem echoed in her mind. Then her mind skipped again, and this time Alex’s voice was in her ear as though he were narrating Will’s document aloud for her: “Our two souls, therefore…” She finished the line from the source, in Donne’s poem, without a pause, “…which are one, Though I must go, endure not yet A breach, but an expansion…” Then she heard Alex’s voice again in her brain: “I am what I am, and what I am is what I am. I have a Will to be what I am.” The words swam in her head, and her feet traced back, and then forth, and then around; the flickering candles made her light-headed and aware she’d missed eating any lunch. She felt as though heaven indeed beckoned. She loved the sensation of having to be so careful with your steps, but so free with your soul.

She opened her eyes very suddenly—to break the spell of the voice within. She thought she saw a man move out of the center of the labyrinth, when she’d believed she was alone. She shivered: someone had walked on her grave. She swung back to see him again, and caught only the movement of the flames, the lights. And then Alex’s gentle, rich voice was back in her head, comforting and calming. “ The truth is so; And this the cranny is, right and sinister, Through which the fearful lovers are to whisper.” She smiled. It was uncanny. She should be distilling her spiritual thoughts. The words—every single word from Will’s sheet—brought Alex back to her. They were fearful lovers; she could hear him whisper, and they appeared to have only a crack in time, like a cranny, to catch each other. With a missed step, one could fall irretrievably behind.

She faced the Great Rose Window now; and she could smell her own perfume drifting back into her face. It was another draft, and it made the flames bend back and forth. She felt the movement again of someone in the labyrinth, but it was a trick of the light, and it made her tremble slightly. She heard Alex’s voice soothing her, calming her down, helping her breaths to slow. Somehow he was there with her. He must be thinking about her, she decided. “The heart is a square too.” She stepped into the very center of the labyrinth, where there had once been a representation of Theseus, the guide had said. She felt something brush against her going the other way, and she held her skirt close to herself, suddenly worried by the candles. Then she relaxed. Again came a breeze, which wafted back at her the scent Alex had given her for Christmas, and she felt a physical warmth beside her, heard his voice right in her ear, as though he was standing immediately beside her. “And I am halfway through the orbit.” It was Alex’s voice, definitely.

Or was it? Her eyes had been lazy, half closed; and she opened them again. She sucked in a breath. Alex’s face rippled in the haze of light and rose-scented heat from the hundred candle flames. His face was not perfectly shaved—was actually quite stubbly. His hair was longer and even a little bit curlier than she had seen it that night on the boat—not nearly as pristine as he had been on her birthday. She realized it was only in her mind’s eye; but it appeared palpable. “Look no further than the day, My alpha and my omega.” The voice again. Kind, reassuring, rich, musical. “Make of these two halves a whole.”

ALEX DID HIS SUMS, AND SAW AT ONCE THAT THE TABLET OF JUPITER, which was drawn on one small sheet of vellum, made the exact squares that satisfied Will’s sketch. Halfway through—this sheet was the midpoint, now he was sure. He’d assumed it was the first piece of the puzzle. He took up his pencil again. My alpha and my omega. Someone whose beginning was also their end—the same day, or place? Alex had a flash of inspiration, and he reached a book from the shelf. He checked a date. Then he stood up and took the Bible out of the collection of items that had only recently come back from the coroner’s from among Will’s personal effects. It was a modern version of the King James—the Old King’s Book, perhaps? A song of equal number. He glanced at the Song of Solomon, of which he now remembered Will had a copy in French among his things from France; but this wasn’t strictly numbered, per se; had Will made the same leap and the same mistake? So he tried the numbered songs of Psalms instead.

A DREAMY SENSATION NOW ENVELOPED LUCY. SHE WAS FLOATING IN A field of flowers and flames; she heard the voice she immediately understood she loved best; and her heart beat with a wildness and pleasure she’d never felt. She was aware that the thudding and thrumming was dangerously like a heart attack, because she was letting herself go; but she was not afraid, as she was not alone. “Equal number of paces forward from the start…” she recalled from Will’s text. She realized she was halfway around the year, virtually to the day, from the date she’d had her lifesaving operation; from the autumn to the spring equinox. It was halfway around the vital path of the first crucial year. And she was turning from the center of the labyrinth now, ready to walk outward, an equal number of paces to the end of it. “Our two souls are one.” Alex’s voice was beside her, inside her, again; and then, “I am what I am, and what I am is what you will see.” She knew what the words on the copied sheet said, even if not in strict order. Our two hearts are one, she thought; and her eyes widened. Oh dear God! My alpha and my omega. My beginning and end.

ALEX STARTED WITH PSALM 23, “THE LORD IS MY SHEPHERD.” IT DIDN’T yield any cryptic clues or messages, he thought, nothing unusual. So he doubled the number, treating the number twenty-three as a half, and making of it a whole. It brought him to Psalm 46; and he counted the same number of words—or paces—forward. He wrote down the word this brought him to on the back of Will’s postcard from Chartres. Then he counted the same number of words backward, and wrote down this second word beside the first. Alex’s breathing hushed and background noise seemed stilled. He’d created an intriguing new compound word of iconic significance. It produced something utterly extraordinary when he married it to the name he’d written right at the start, William.

He tossed the pencil onto the table and mouthed the whole thing, then laughed. Max looked up at him, puzzled. He had to show this to Lucy: she was in this with him. In the labyrinth.

LUCY REACHED THE LAST STEP OF THE LAST LOOPING COIL OF THE PATH before she emerged from the intensity of candlelight and flame. She was barely aware of anyone else’s presence. She had understood the vital words on this document that accompanied the key. Someone’s omega had been her alpha. What I am is what you will see. She had seen. She knew the name. She had to tell Alex.

She kissed the verger, put some money in the guide’s hand, and ran with light dancing steps from the great cathedral, out onto the North Porch. She switched on her cell phone and dialed the number, hardly pausing for breath.

“Hello?” Slight excitement in his voice. The synchronicity didn’t surprise him.

She wanted to tell him immediately how she felt, that she was sorry for being stubborn when he’d rung earlier; but someone was walking quite close to her, and she felt self-conscious, so she began differently. “I’ve got to tell you something. Well, perhaps, actually, I want to ask you something. Maybe I should come back tomorrow.” Her thoughts were in a whirl: how much to say, how to express thoughts that scorched her brain like a thousand candles.

“I want to see you too.” Alex was steady but his voice was resonating. “I don’t want you to spoil your weekend, but I’ve come to a realization and I’ve got to show you something absolutely extraordinary. I’ve solved the riddle in the text that you have with you.”

“Yes, so have I! Look, Alex.” She said his name again, and he waited patiently for her to talk. It was difficult. She was trying to find words to ask a strange and complicated question and confide complex emotions, but there were people around. Yet she was bursting inside, and she had to share it—with him alone. “Alex? Are you there?”

“Look, if you do want to stay another day, would you perhaps come back sooner on Sunday? I’m taking Max back to Anna’s by three—possibly even earlier. Sunday afternoon would be a perfect time. I could cook.” Idiot, he thought to himself; if I were Will I’d just tell her I wanted her, and get her back here now. He’d push everything else to one side and get to the point. If Max was there, then Max was there. Life’s like that sometimes.

“Lucy?”

She’d gone silent, her gaze suddenly caught by a man who’d been standing almost behind her, listening. He was now looking straight at her, moving toward her. She was very uncomfortable. It was the same immaculately dressed man who’d leered at her in the church earlier in the day.

“Alex!” Her voice was panicked. He heard the phone drop, muffled voices, Lucy’s small cry like a child, and then all sounds retreated from the source of his hearing. He heard a clock chime the half hour. Then nothing.